French’s mood had not lightened when he returned to the Yard. He had been unfortunate in not finding anyone he knew at the restaurant, with the result that during his solitary lunch he had been unable to banish the case from his mind. Now as he settled down to work at it again it was from a barren sense of duty rather than with any hope that he might obtain results.

He began by writing to the Scotch police authorities of Campbeltown to get a report from Dr MacGregor as to the injury to Victor’s knee. Then he sent a man to the Patent Office to find out if Sir John had provisionally protected his invention. Finally he set himself doggedly to review Joss’s statement so as to satisfy himself that there really was nothing to be learned about it. Part of the story he believed absolutely. The scheme of getting Sir John into Joss’s power in an adjoining sleeping berth and there drugging him rang true. So did the somewhat intricate operations with the doors and the search for the plans. The stories told to Sir John, moreover, must have been somewhat as stated by Joss, judging by the way in which the old man had acted on them. But where French doubted the statement was in its finale. Had Joss’s search proved unavailing? Had he not really found and stolen the plans? To French this seemed more than likely. It might well be that Joss had actually replaced the packet with a dummy so that the old man had not learnt of his loss till he reached Belfast.

But though Joss’s tale might not be entirely true, it seemed to contain enough truth to relieve himself and his friends from suspicion of the murder. Naturally, therefore, it did nothing to clear up the fate of Sir John Magill. The reason for the old gentleman’s visit to Sandy Row was now known, but not what took place there. It did not explain why Sir John had gone to the Cave Hill, still less did it account for the extraordinary episodes at Larne and Whitehead. No, there was more in the whole business than he, French, had yet visualised.

He turned once again to his Breene theory. Did this statement of Joss’s support or rebut it?

It didn’t seem to do either. It was now clear that Breene had not been responsible for Sir John’s visit to Belfast. But on the other hand might he not have taken advantage of it? French did not know. He sighed wearily as he considered the point and reconsidered it and then considered it again.

One thing at least became increasingly certain. Here in England the solution was beyond his reach. It must lie on the Irish side. He decided that if Chief Inspector Mitchell agreed he would write to Rainey that very evening pressing his view of the situation. Then he could drop the case. There was plenty of work for him in London.

But it happened that just then the post came in with a letter from the police headquarters in Belfast. Superintendent Rainey wrote that certain discoveries which had been made by his staff seemed to indicate that the key to the Magill mystery must lie in England, and that if convenient to all concerned, he would send Sergeant M’Clung over for a consultation. At this French swore, but he sent a wire that he could see M’Clung at any time. A couple of hours later there was a reply that the sergeant was leaving that evening.

French, considerably disgruntled, swore more viciously. It was not indeed until he had reached his home and had his supper that he settled down to his usual state of complacency.

He reached the Yard next morning to find that M’Clung had already arrived.

‘You weren’t long in Ireland,’ French greeted him. ‘Why on earth did they send for you if they didn’t want you?’

M’Clung grinned.

‘They’ve made some discoveries, Mr French,’ he explained. ‘They sent for me to hear the details so that I might come over and tell you.’

French shook his head.

‘It’s a bad business,’ he declared. ‘A very bad business. Do you know that yesterday I was just going to write you that the whole solution must lie with you and that I might withdraw from the case? And now you’ve proved that it lies over here.’

‘Well, we haven’t just got that length, Mr French,’ M’Clung returned with the suspicion of a smile. ‘What we think is that it doesn’t lie in Northern Ireland. We wouldn’t like to take it on us to say just where it does lie.’

French grunted.

‘I suppose that means that you know nothing about it?’

M’Clung laughed outright.

‘As you know, sir,’ he pointed out, ‘officially that could never be the case. But between you and me and the wall it’s about the size of it.’

‘Well, you may take it from me that it doesn’t lie over here.’

‘But it must lie somewhere, sir,’ M’Clung said innocently.

French glanced at him keenly.

‘Oh, you think so, do you? Did you get my letter about Breene? No? Well, sit down on that chair and put on that filthy pipe of yours and let’s hear the great discovery.’

M’Clung told his tale well. He had the gift of narration, and French could picture the events occurring almost as if he was seeing them.

It seemed that after French’s departure the authorities of Northern Ireland had concentrated on trying to trace in detail the movements of Sir John Magill from the moment he left Sandy Row until his body reached what his murderer at least believed would be its last resting place at Lurigan.

They had considered and rejected a theory that Sir John had been murdered by political enemies. Though the old man had always been a staunch Unionist, the police thought it unlikely that he had ever incurred the really serious enmity of his political opponents. Especially unlikely was it that his death, had it been decided on, would have been delayed for so long a period. The ‘troubles’ were definitely over and had been for years. Moreover, the police knew practically all the gunmen in the city, men who in many cases were known to have committed murder, but against whom nothing could be proved. These were checked up and the police were satisfied that none of them had recently been on the warpath.

After considerable thought, Superintendent Rainey had decided to fall back on publicity. A reward for information as to the deceased’s movements was therefore offered. Advertisements were inserted in the local papers, and notices were exhibited at police barracks and elsewhere, throughout the country.

On the day of the newspaper insertions, a Mr Francis M’Comb called at police headquarters. He said that he had read the advertisement and believed he had seen the man in question.

He stated that on Thursday, October 3rd, which was the day of Sir John’s visit to Belfast, he and his wife had taken some English visitors up the Cave Hill. They had climbed the Sheeps’ Path from the Antrim Road to near the top, returning by the same route. On reaching their home on the Malone Road about six o’clock his wife missed an earring. It was not intrinsically of great value, but for sentimental reasons she prized it highly. She was so much upset about the loss that M’Comb volunteered to return immediately to the place where she thought she had dropped it—a slippery bit of the path on which she had had a fall. He did so and found the trinket, and it was when he was returning down the path to the Antrim Road that he saw the man.

‘I’ll have to explain what the path is like so that you’ll understand the story,’ went on M’Clung. ‘The lower part passes through private grounds and it’s fenced off from these by barbed wire palings, set back fifteen or twenty feet from each side and with laurels in patches between it and the fences. When you leave the Antrim Road the path leads through trees at first, but in two or three minutes you come to a clearing on the left side. Near the top of the clearing there’s a clump of rhododendrons, about fifty feet across. It’s quite a thick clump and it lies about sixty or seventy feet out from the side of the clearing and the path. I could draw it if you don’t follow me.’

‘It’s clear enough so far,’ French admitted cautiously.

M’Clung nodded.

‘Well, M’Comb was coming down after finding the ear-ring. When he was passing the clearing he happened to look up and he saw a man come out of the clump. The man looked round in a stealthy sort of way and then he hurried across the clearing towards the path. M’Comb was a bit surprised, but he thought it was no business of his and he went on down to the Antrim Road.

‘Just near where the path comes out there is a tramway halt and M’Comb went to it and stood waiting for a car. He hadn’t been there two minutes when the man appeared. He followed over to the halt and M’Comb had a good look at him. Mr French, it was Sir John Magill!’

‘Good,’ said French, considerably interested. ‘What time was that?’

‘About a quarter past seven. It was getting dusk, but on account of being near the man M’Comb was able to see him clearly. Then a tram came along and they both got on board, Sir John inside and M’Comb on the top.’

Trams from the Antrim Road, M’Clung explained, reach the City Centre by two routes, via Carlisle Circus or via Duncairn Gardens. The Duncairn Gardens route takes a detour which brings it within a few yards of the Northern Counties station of the L.M.S. railway, that for Whitehead and Larne. This particular car was going via Carlisle Circus, therefore had it contained passengers who wished to travel by rail, these would have alighted at the top of Duncairn Gardens and either taken the ten-minute walk down the Gardens to the station or waited for a following car.

It happened by a stroke of luck that M’Comb, who was sitting at the back of the tram, saw Sir John alight, not indeed at Duncairn Gardens, but a couple of blocks before they reached it. As the tram passed on Sir John crossed the sidewalk and disappeared into a shop.

The police at once got M’Comb to stop a tram at the place in question, and asked him to mount to the top and from there to point out the shop. This he was unable to do, but he showed them the block containing it.

Inquiries at all the shops in the block soon gave the desired information. The young lady behind the counter of a confectioner’s stated that at about half past seven on an evening about the date mentioned a man answering the given description had come in and bought some fruit and nut chocolate. The price was one-and-six and he had offered her a pound in payment. She was out of change, and realising that she would have to go out for it and leave her customer alone in the shop, the girl gave him a very searching look. It was this fact that had impressed his appearance on her mind. For the same reason she had glanced at the clock and now remembered the hour. On receiving his change the man had left immediately, turning in the direction of Duncairn Gardens.

Both this young lady and M’Comb declared Sir John’s photograph shown them by the police was that of the man in question. The girl had seen him in a better light than M’Comb, and she stated that he looked dishevelled and that there was moss on his coat, as if he had been lying on the grass.

It was seen at once that the hours mentioned by these two witnesses worked in sufficiently well with what was already known of Sir John’s movements. He had travelled to Whitehead by the 8.00 train, and had he walked down the Sheeps’ Path and bought his chocolate when stated, he would just have arrived at the station about a quarter to eight.

The police next asked M’Comb to accompany them to the Sheeps’ Path and to point out the spot where Sir John had emerged from the rhododendrons. A careful search was made of the surroundings with the result that some further very interesting discoveries were made. In the heart of the clump a small space of some eight feet square was found to have been trampled down. Here twigs had been placed to make a rude couch and branches had been cut and pushed into the interstices between the bushes with the evident object of making the retreat even more invisible from outside.

But these discoveries paled into insignificance compared to M’Clung’s last find. Close by and equally hidden by the bushes were traces of digging. Cut sods were piled over a little mound of fresh soil and scraps of clay lay on the surrounding grass. It was not another grave—it was too small for that. Rather it suggested treasure trove.

Spades were sent for and the soil was removed. Below was loose clay. This was lifted out and at a depth of a couple of feet the treasure was come on.

Folded into a tight roll was a cloak or garment of very peculiar shape. It was made of dark brown velvet and consisted of a complete suit and hat in one. The body portion was made like a mechanic’s overalls, with full length legs and arms and an opening up the front closed by buttons. Attached to the body at the back of the neck was a helmet like a monk’s cowl. The garment was roughly made, and coarsely sewn. But it was of a small size. In fact it would have exactly fitted Sir John Magill.

French gave vent to an exclamation of amazement.

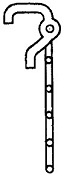

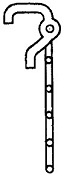

‘That isn’t everything yet, sir,’ M’Clung went on, delighted at the reception his story was getting. Wrapped up inside the cloak was a short piece of light rope ladder. It was made with dark brown silk ropes and thin rungs of dark brown cane. At one end the ropes terminated in a pair of light metal hooks, painted black. These hooks were of a peculiar shape, rather like notes of interrogation, the ladder being attached halfway down the curve. Altogether the ladder was just under six feet long.

French swore.

‘What under the sun did you make of that?’ he asked.

M’Clung shrugged.

‘What could we make of it, sir?’ he returned. ‘The only suggestion that I’ve heard was that Sir John was taking part in the ceremonial of some secret society. I’m neither an orangeman nor a mason, but I understand the ladder is a symbol in both orders. And Sir John was high up among the orangemen. All the same that didn’t strike me as reasonable. Would it you, sir?’

French shook his head.

‘More like a burglar’s outfit, if you ask me,’ he answered. ‘But I’d like to think over it a bit before I make any suggestions. I’ve never come across anything like this before. What games that old man could have been up to at his time of life beats me.’

French indeed did feel completely puzzled by this new development.

‘Curse the thing,’ he grumbled. ‘There’s no making head or tail of it.’ He moved uneasily, then went on with a change of manner. ‘So far as I can see, M’Clung, the one thing that comes out of it is what I said: that the whole trouble lies on the Irish side of the Channel. Why don’t you go and solve it instead of coming over here and worrying me?’

M’Clung grinned.

‘Och, Mr French,’ he answered innocently. ‘Sure, we couldn’t do without your help anyway.’

‘Oh, you couldn’t, couldn’t you?’ French grunted suspiciously. ‘Well, if that’s so get along and tell me why you think your case lies over here.’

M’Clung knocked the ashes out of his pipe and proceeded slowly to refill it. When he answered he spoke with evident seriousness.

‘Well, it’s what the superintendent thinks really, sir, though, mind you, I agree with him. He thinks the explanation must lie over here simply because there’s nothing on our side to account for it.’

‘In other words a confession of failure?’ French suggested.

M’Clung shrugged.

‘The superintendent didn’t put it just that way,’ he explained. ‘He said that though we had nothing, you had that affair of Coates and the sleeping berths in the train.’

‘That’s a washout.’

M’Clung looked startled.

‘Washout, sir?’ he repeated. ‘That’s bad. You mean there’s nothing on this side to account for it either?’

‘That’s exactly what I do mean,’ French growled. He glanced suspiciously at the other, then apparently satisfied, went on: ‘Well, I’ll tell you. This man “Coates” was really Joss, and he admitted giving the false name and volunteered all that about the communicating door as well as saying he’d drugged Sir John,’ and French described his interview in detail.

M’Clung was manifestly disappointed.

‘The superintendent’ll be sorry to hear that, sir. He was counting a lot on that Coates business.’

‘As a matter of fact,’ French admitted, ‘so was I; it was the only tangible thing we had. However, it’s gone west and that’s all there’s to it.’

Though French spoke despondently his manner belied his words to such an extent that M’Clung asked hopefully: ‘Have you anything in your mind, sir?’

For a moment French did not reply. Then he rose, and going to the vertical file in the corner of his room, he took out the copy of the letter he had sent to Belfast on the previous evening.

‘That’s what I had in my mind yesterday midday,’ he said. ‘Since I heard Joss’s story I’m not so sure about it. Read it and we’ll discuss it.’

M’Clung was eminently polite about the Breene theory, but he was clearly not impressed by it. ‘You know, sir,’ he said deferentially, ‘we went into that. Unless our people are pretty badly out, Breene was in the hotel all the time.’

‘Your people may be absolutely right,’ French admitted, ‘but in the light of this business about the engagement I suggest you go into it again and make quite sure.’

M’Clung was agreeably reassuring as to that. Rainey, he was certain, would put the matter beyond the faintest shadow of doubt. They talked of Breene for some time, then the conversation swung back to Sir John.

‘I wonder,’ French said absently, as if following out a private train of thought. Then he became silent as he considered an idea which had suddenly flashed into his mind. ‘By Jove, yes, Sergeant! Sir John would hide himself all right! Look at it this way.’

Keen interest once again showed in French’s manner. He laid down his pipe, sat forward in his chair, and began to tick off his points on his fingers.

‘Here’s a problem for you,’ he resumed. ‘Would a successful robbery not involve murder? In other words, could such a secret be stolen so long as Sir John remained alive?’

‘Was it protected?’ M’Clung questioned.

‘No, it wasn’t, but it doesn’t matter two hoots whether it was or not. Come now: use your grey cells, as that Belgian would say. Put yourself in Joss’s place and assume you’d got the plans. Could you have used them?’

M’Clung remained silent, then he shook his head.

‘Very well,’ French resumed, ‘let us consider what Joss would expect would happen if Sir John remained alive. Sir John would reach Sandy Row, and because the address he had been given proved non-existent, he would realise something was wrong. He would search for his plans and find they were missing. What then would he do? He would go to the police, report his loss, describe his process and declare his suspicions of Coates. The police would get busy and find Joss. But they wouldn’t arrest him. And why? Because they would have no proof against him. The police and Sir John would be, so to speak, in a position of stalemate. They couldn’t move.’

French paused and looked expectantly at the sergeant, who nodded emphatically.

‘Now,’ went on French, ‘Sir John would be in a position of stalemate, but there’s more in it than that. So Joss would be also. Joss couldn’t use his knowledge. Directly “Sillin” or anything like it appeared on the market the police would be on to it. They would find out the process and see that it was the same as Sir John’s and a short investigation would enable them to connect Joss with the manufacture. If he wasn’t personally concerned in it they’d be able to trace up a sale. Anyway they’d get him: As sure as that stuff came on the market Joss would go to jail. Now Joss must know all this, so he must see that his theft could be of no value to him.’

Again French paused to receive the sergeant’s tribute.

‘What then,’ he went on, ‘would stand between Joss and his fortune? Just one thing—Sir John Magill’s life. If Sir John could be kept silent all would be well. It follows absolutely.’

M’Clung in his delight lapsed into the vernacular.

‘Boys, Mr French, but that’s powerful!’ he declared. ‘I never heard the like of it!’

‘But do you agree with it?’ demanded French, who had not as yet fully grasped Ulster idiom.

‘I do so.’ M’Clung could be comfortably direct when he desired.

‘Good. Then if we’re right so far something else follows. I think we can say that an accomplice must have met Sir John in Sandy Row. If Joss knew just when the old man would make his discovery, he would be bound to guard against it. Someone would meet Sir John and see to it that he didn’t go to a police station.’

M’Clung, with a suspicion of what was coming, agreed less warmly.

‘Very well,’ said French, ‘there’s the clue on your side and you’ve got to follow it up.’

M’Clung’s enthusiasm evaporated instantaneously.

‘Would you not think, Mr French,’ he suggested craftily, ‘that they were all in it?’

‘All?’

‘Yes, the whole darned launch party.’

This was no new idea to French. Again and again he had suspected it and again and again he had supposed he was mistaken. He really didn’t know. Of course—

‘And Malcolm too,’ went on M’Clung.

French started. Was there any help here? What if Malcolm could have been that mysterious individual whose existence he had just postulated?

‘By Jove, M’Clung, if you people can prove that Malcolm was a partner with the others it’ll be the beginning of the end. What about Malcolm meeting his father in Sandy Row, eh?’

M’Clung nodded profoundly.

‘That’s the style, sir. That’s what I was thinking myself. Malcolm. Or maybe Breene,’ he added tactfully. ‘Anyway we’ll make inquiries. We should find out easy enough.’

For a solid couple of hours the two men continued discussing the affair, but without reaching anything more illuminating. Finally it was agreed that the two lines they had considered were to be explored to the utmost of their capacity. M’Clung and the Belfast police were to assume that someone met Sir John in Sandy Row and were to concentrate on finding this person, whether it were Magill or Breene or someone hitherto unknown. French on his part was to assume that the whole four members of the launch party were involved and was to concentrate on the trip, trying to obtain further links between the travellers and the affairs of Sir John.

While these decisions were taken, it was without enthusiasm on either side, each of the detectives believing that success, if attainable at all, lay in the line his companion was to work.

‘I’ll tell you what it is,’ French declared finally. ‘You and your Belfast superintendent are the darnedest pair of nuisances I’ve struck for many a long day. Come out and have a bit of lunch.’