The law of existence prescribes uninterrupted killing, so that the better may live.

—Adolf Hitler, 1941

Human civilization currently faces many serious dangers. The most immediate catastrophic threat, however, does not come from environmental degradation, resource depletion, or even asteroidal impact. It comes from bad ideas.

Ideas have consequences. Bad ideas can have really bad consequences.

The worst idea that has ever been is that the total amount of potential resources is fixed. It is a catastrophic idea, because it sets all against all.

Currently, such limited-resource views are quite fashionable among not only futurists but much of the body politic. But if they prevail, then human freedoms must be curtailed. Furthermore, world war and genocide would be inevitable, for if the belief persists that there is only so much to go around, then the haves and the want-to-haves are going to have to duke it out, the only question being when.

This is not an academic question. The twentieth century was one of unprecedented plenty. Yet it saw tens of millions of people slaughtered in the name of a struggle for existence that was entirely fictitious. The results of similar thinking in the twenty-first could be far worse.

The logic of the limited-resource concept leads down an ever more infernal path to the worst evils imaginable. Basically, it goes as follows:

1. Resources are limited.

2. Therefore, human aspirations must be crushed.

3. So, some authority must be empowered to do the crushing.

4. Since some people must be crushed, we should join with that authority to make sure that it is those we despise rather than us.

5. By getting rid of such inferior people, we can preserve scarce resources and advance human social evolution, thereby helping to make the world a better place.

The fact that this case for oppression, tyranny, war, and genocide is entirely false has made it no less devastating. Indeed, it has been responsible for most of the worst human-caused disasters of the past two hundred years. So let's take it apart.

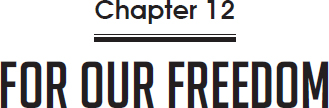

Figure 12.1. Contrary to Malthus's theory, human global well-being has increased with population size, and at an accelerating rate.

Two hundred years ago, the English economist Thomas Malthus set forth the proposition that population growth must always outrun production as a fundamental law of nature. This theory provided the basis for the cruel British response to famines in Ireland and India during the latter part of the nineteenth century, denying food aid or even regulatory, taxation, or rent relief to millions of starving people on the pseudoscientific grounds that their doom was inevitable.1

Yet the data show that the Malthusian theory is entirely counterfactual. In fact, over the two centuries since Malthus wrote, world population has risen sevenfold, while inflation-adjusted global gross domestic product per capita has increased by a factor of 50, and absolute total GDP by a factor of 350.

Indeed, it is clear that the Malthusian argument is fundamentally nonsense, because resources are a function of technology, and the more people there are and the higher their living standard, the more inventors, and thus inventions, there will be—and the faster the resource base will expand.

Our resources are growing, not shrinking, because resources are defined by human creativity. In fact, there is no such thing as “natural resources.” There are only natural raw materials. It is human ingenuity that turns natural raw materials into resources.

Land was not a resource until people invented agriculture, and it is human ingenuity, manifested in continuous improvements in agricultural technology, that has multiplied the size of that resource many times over.

Petroleum was not originally a resource. It was always here, but it was nothing useful. It was just some stinky black stuff that sometimes oozed out of the ground and ruined good cropland or pasture. We turned it into a resource by inventing oil drilling and refining, and by showing how oil could be used to replace whale oil for indoor lighting, and then, later, by liberating humanity with unprecedented personal mobility.

This is the history of the human race. If you go into any real Old West antique store and look at the things owned by the pioneers, you will see things made of lumber, paper, leather, wool, cotton, linen, glass, carbon steel, maybe a little bit of copper and brass. With the arguable exception of lumber, all of those materials are artificial. They did not, and do not, exist in nature. The civilization of that time created them. But now go into a modern discount store, like Target. You will see some items made of the same materials, but much more made of plastic, synthetic fibers, stainless steel, fiberglass, aluminum, and silicon. And in the parking lot, of course, gasoline. Most of the materials that make up the physical products of our civilization today were unknown 150 years ago. Aluminum and silicon are the two most common elements in the Earth's crust. But the pioneers never saw them. To the people of that time, they were just dirt. It is human invention that turned them from dirt into vital resources.

There are things around today that clearly could become major resources but are not yet. Uranium and thorium were not resources at all until we invented nuclear power, but we are going to have to do a bit more inventing to get all the bugs out so as to unleash their truly vast potential. The same thing is true for solar energy, which needs to be made cheaper if it is to become truly practical as a baseload energy source. But this is happening, year by year, through innumerable inventions, great and small. Other enormous resources, more distantly in view, await the invention of ways to use them; for example, there is deuterium in seawater that could provide fusion power; there are methane hydrates and stratospheric winds. Today, the revolutionary new resource is shale. Twenty years ago, shale was not a resource. Today, as a result of the invention of new techniques of horizontal drilling and fracking, it's an enormous resource. In the past ten years, we've used it to increase US oil production 120 percent, from five million to eleven million barrels of oil per day. In the past twenty years, America's gas reserves have tripled, and we can and will do that and more for the world at large.

So the fact of the matter is that humanity is not running out of resources. We are exponentially expanding our resources. We can do this because the true source of all resources is not the earth, the ocean, or the sky. It is human creativity. It is people who are resourceful.

It is for this reason that, contrary to Malthus and all of his followers, the global standard of living has continuously gone up as the world's population has increased, not down. The more people—especially free and educated people—the more inventors, and inventions are cumulative.

Furthermore, the idea that nations are in a struggle for existence is completely wrong. Darwinian natural selection is a useful theory for understanding the evolution of organisms in nature, but it is totally false as an explanation of human social development. This is so because, unlike animals or plants, humans can inherit acquired characteristics—for example, new technologies—and do so not only from parents but from those to which they are entirely unrelated. Thus, inventions made anywhere ultimately benefit people everywhere. Human progress does not occur by the mechanism of militarily superior nations eliminating inferior nations. Rather, inventions made in one nation are transferred all over the world, where, newly combined with other technologies and different mind-sets, they blossom in radical new ways. Paper and printing were invented in China, but they needed to be combined with the Phoenician-derived Latin alphabet, German metal-casting technology, and European outlooks concerning freedom of conscience, speech, and inquiry to create a global culture of mass literacy. The same pattern of multiple sourcing of inventions holds true for virtually every important human technology today, from domesticated plants and animals to telescopes, rockets, and interplanetary travel.

Based on its inventiveness and its ability to bring together people and ideas from everywhere, America has become extremely rich, inciting envy elsewhere. But other countries would not be richer if America did not exist, or were less wealthy or less free. On the contrary, they would be immeasurably poorer.

Similarly, America would not benefit by keeping the rest of the world underdeveloped. We can take pride in our creativity, but in fact we would be much better off if all other people had as good a chance to develop and exercise their potential, and thus contribute to progress, as we do.

Nevertheless, so long as humanity is limited to one planet, the arguments of the Malthusians have the appearance of self-evident truth, and their triumph can have only the most catastrophic results.

Indeed, one has only to look at the history of the twentieth century, and the Malthusian/national social Darwinist rationale that provided the drive to war of both Imperial and, especially, Nazi Germany to see the horrendous consequences resulting from the widespread acceptance of such myths.

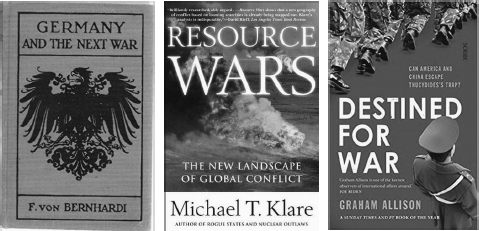

As the German General Staff's leading intellectual, General Friedrich von Bernhardi, put in his 1912 bestseller Germany and the Next War:

Strong, healthy, and flourishing nations increase in numbers. From a given moment they require a continual expansion of their frontiers, they require new territory for the accommodation of their surplus population. Since almost every part of the globe is inhabited, new territory must, as a rule, be obtained at the cost of its possessors—that is to say, by conquest, which thus becomes a law of necessity.2

Having accepted that war was inevitable, the only issue for the Kaiser's generals was when to start it, and they chose sooner rather than later so as not to give Russian industry a chance to develop.

Thus in 1914, the unprecedentedly prosperous European civilization was thrown into a completely unnecessary and nearly suicidal general war. A quarter century later, the same logic led the Nazis to do it again, with not merely conquest but systematic genocide as their insane goal.

To be perfectly clear on this point, the crimes of the Nazis were not just committed in secret by a few satanic leaders while the rest of the good citizens proceeded with their decent daily lives in well-meaning ignorance. In point of fact, such blissful ignorance was not possible. At its height, there were more than twenty thousand killing centers in the Third Reich, and most were discovered by Allied forces within hours of their entry into the vicinity—as the stench of their crematoria made them readily detectable. Something on the order of a million Germans were employed operating these facilities, and several million more were members of armed forces or police units engaged in or supporting genocidal operations.3 Thus nearly every German had friends or family members who were eyewitnesses to or direct perpetrators of genocide, who could, and did, inform their acquaintances as to what was happening. (Many sent photos home to their parents, wives, or girlfriends, depicting themselves preparing to kill, killing, or posing astride the corpses of their victims.) Moreover, the Nazi leadership was in no way secretive about its intent; genocide directed against Jews and Slavs was the openly stated goal of the party that eighteen million Germans voted for in 1932. On March 20, 1933, less than two months after the Nazi assumption of power, SS leader Heinrich Himmler made it clear that these voters would have their wishes gratified, by announcing the establishment of the first formal concentration camp, Dachau, at a press conference. Furthermore, the implementation of the initial stages of the genocide occurred in public, with systematic degradation, beatings, lynchings, and mass murder of Jews done openly for all to see in the Reich's streets from 1933 onward, with the most extensive killings, such as those of the November 10, 1938, Kristallnacht pogrom, celebrated afterward at enormous public rallies and parties.

So the contention that the Nazi-organized Holocaust took place behind the backs of an unwilling German population is patently false. Rather, the genocidal Nazi program was carried out—and could only have been carried out—with the full knowledge and substantial general support of the German public. The question that has bedeviled the conscience of humanity ever since then: How could this have happened? How could the majority of citizens of an apparently civilized nation choose to behave in such a way? Some have offered German anti-Semitism as the answer. But this explanation fails in view of the fact that anti-Semitism had existed in Germany, and in many other countries such as France, Poland, and Russia to a sometimes much greater extent, for centuries prior to the Holocaust, with no remotely comparable outcome.

Furthermore, the Nazi genocidal program was not directed just against Jews but also at many other categories of despised people, including invalids, Romany people, and the entire Slavic race. Indeed, the Nazis had drawn up a plan, known as the Hunger Plan, for depopulating Eastern Europe, the Balkans, and the Soviet Union through mass starvation following their anticipated victory, on the insane supposition that by ridding the land of its farmers they could make more food available.4 It should be noted that the partial implementation of this plan in occupied areas not only caused tens of millions of deaths but contributed materially to the defeat of the Third Reich, as it made it impossible for the Nazis to mobilize the human potential of the conquered lands on their own behalf. But not even such clear practical military and economic considerations could prevail against the power of a fixed idea.

In other words, as the Nazi leadership itself repeatedly emphasized, the genocide program was not motivated by mere old-fashioned bigotry. It certainly took advantage of such sentiments among rustics, hoodlums, and others to facilitate its operations. But it required something else to convince a nation largely composed of serious, solid, dutiful, highly literate, and fairly intellectual people to devote themselves to such a cause. It took Malthusian pseudoscience.5

Hitler himself was perfectly aware of the central importance of such an ideological foundation for his program of genocide. As noted Holocaust historian Timothy Snyder wrote in a September 2015 New York Times op-ed: “The pursuit of peace and plenty through science, he claimed in Mein Kampf, was a Jewish plot to distract Germans from the necessity of war.”6

Once again, to be clear, the issue is not whether space resources will be made available to Earth in the proximate future. Rather it is how we, in the present, conceive the nature of our situation in the future. Nazi Germany had no need for expanded living space. Germany today is a much smaller country than the Third Reich, with a significantly higher population, yet Germans today live much better than they did when Hitler took power. So, in fact, the Nazi attempt to depopulate Eastern Europe was totally nuts, from not only a moral but also a practical standpoint. Yet, driven on by their false zero-sum beliefs, they tried anyway.

If it is allowed to prevail in the twenty-first century, zero-sum ideology will have even more horrific consequences. For example, there are those who point to the fact that Americans are 4 percent of the world's population yet use 25 percent of the world's oil. If you were a member of the Chinese leadership and you believed in the limited-resource view (as many do—witness their brutal one-child policy), what does this imply you should attempt to do to the United States?

On the other hand, there are those in the US national security establishment who cry with alarm at the rising economy and concomitant growing resource consumption of China. They project a future of “resource wars,” requiring American military deployments to secure essential raw materials, notably oil.7

As a result of acceptance of such ideology, the United States has initiated or otherwise embroiled itself in conflicts in the Middle East costing tens of thousands of American lives (and hundreds of thousands of Middle Eastern lives) and trillions of dollars. For 1 percent of the cost of the Iraq War, we could have converted every car in the United States to flex fuel, able to run equally well on gasoline or methanol made from our copious natural gas.8 For another 1 percent, we could have developed fusion power. Instead, we are fighting wars to try to control oil supplies that will always be sold to the highest bidder no matter who owns them.

Figure 12.2. Self-fulfilling prophecies. In 1912, the theoreticians of the German General Staff said it was inevitable that Germany would have to wage war for living space. In 2001, American geostrategists proclaimed we would need to fight for oil. Both were wrong. Both set the stage for disaster. Much worse could be on the way if such zero-sum ideology is not discredited. Image courtesy of Friedrich von Bernhardi, Germany and the Next War, trans. Allen H. Powles (London: Edward Arnold, 1918); Michael T. Klare, Resource Wars (London: Methuen, 1989); Graham Allison, Destined for War (Melbourne: Scribe Publications, 2018).

There were no valid reasons for the first two World Wars, and there is no valid reason for a third. But there could well be one if zero-sum ideology prevails. Despite the bounty that human creativity is producing, there are those in America's national security establishment who today are planning for resource wars against peoples who could and should be our partners in abolishing scarcity. Their equivalents abroad are similarly sharpening their knives against us. This ideology threatens catastrophe.

Today there is a dangerous new anti-Western, antifreedom movement in Russia led by fascist philosopher Aleksandr Dugin, who is attempting to expand it worldwide. (He is doing so with significant success. The American “alt-right” and a host of similar European “identitarian” nativist movements all draw heavily from Dugin's ideas.9 The basic idea is to both balkanize the West and undermine its commitment to humanist ideals by invoking the tribal instinct.) It is the contention of the Duginites that the world would be better off without America, or any other country with liberal values. Indeed, I was present at a conference on global issues held at Moscow State University, Dugin's home turf, in October 2013, when one of his acolytes got up and gave a fiery speech denouncing America for its profligate consumption of the world's resources, including its oxygen supply.10 Such ideas amount to a call for war.

Do we really face the threat of general war? There seems to be no reason for it, and in fact, there isn't. People all over the world today are actually living much better than they ever did before, at any time in human history. But the same was true in 1914. Let us recall that a mere thirty years ago, the world was divided into two hostile camps, ready to spring into action on a few minutes’ notice to destroy each other with tens of thousands of nuclear weapons. That threat vanished—not because of any change in real human circumstances, but due to the disappearance of a bad idea. It can just as quickly reappear with another. As in 1914 and 1939, all it takes is the belief that there isn't enough to go around—that others are using too much, or threatening by their growth to do so in the future—to set the world ablaze.

If it is accepted that the future will be one of resource wars, there are people of action who are prepared to act accordingly.

There is no scientific foundation supporting these motives for conflict. On the contrary, it is precisely because of the freedom and affluence of the United States that American citizens have been able to invent most of the technologies that have allowed China, Russia, and so many other countries to lift themselves out of poverty. And should China (with a population five times ours) develop to the point where its per capita rate of invention mirrors that of the United States—with 4 percent of the world's population producing 50 percent of the world's inventions—the entire human race would benefit enormously. Yet that is not how people see it, or are being led to see it by those who should know better.

Rather, people are being bombarded on all sides with propaganda, not only by those seeking trade wars, immigration bans, or preparations for resource wars, but by those who, portraying humanity as a horde of vermin endangering the natural order, wish to use Malthusian ideology as justification for suppressing freedom. Such arguments sometimes costume themselves as environmentalist, but that is deception. True environmentalism takes a humanist point of view, seeking practical solutions for real problems in order to enhance the environment for the benefit of human life in its broadest terms. It therefore welcomes technological progress. Antihuman Malthusianism, on the other hand, seeks to make use of instances of inadvertent human damage to nature as an ideological weapon of behalf of the age-old reactionary thesis that humans are nothing but pests whose aspirations need to be contained and suppressed by tyrannical overlords to preserve a divinely ordered stasis.

“The Earth has cancer and the cancer is man,” proclaims the elite Club of Rome in one of its manifestos. This mode of thinking has clear implications. One does not provide liberty to vermin. One does not seek to advance the cause of a cancer.

The real lesson of the last century's genocides is this: We are not endangered by a lack of resources. We are endangered by those who believe there is a shortage of resources. We are not threatened by the existence of too many people. We are threatened by people who think there are too many people.

If the twenty-first century is to be one of peace, prosperity, hope, and freedom, a definitive and massively convincing refutation of these pernicious ideas is called for—one that will forever tear down the walls of the mental prison these ideas would create for humanity.

A QUESTION OF FAITH

We believe that free labor, that free thought, have enslaved the forces of nature, and made them work for man. We make the old attraction of gravitation work for us; we make the lightning do our errands; we make steam hammer and fashion what we need…. The wand of progress touches the auction-block, the slave-pen, the whipping-post, and we see homes and firesides and schoolhouses and books, and where all was want and crime and cruelty and fear, we see the faces of the free.

—Colonel Robert G. Ingersoll, Indianapolis speech, 187611

Western civilization is based on the radical individualist proposition advanced by the Greek philosophers Socrates and Plato that there is an innate faculty of the human mind capable of distinguishing right from wrong, justice from injustice, truth from untruth. Embraced by early Christianity, this idea became the basis of the concept of the conscience, which thereupon became the axiomatic foundation of Western morality. It is also the basis of our highest notions of law—the natural law determinable as justice by human conscience and reason, put forth, for example, in the US Declaration of Independence (“We hold these truths to be self-evident…”)—from which we draw our belief that the fundamental rights of humans exist independent of any laws that may or may not be on the books or existing accepted customs. It is also the basis for science, our search for universal truth through the tools of reason.

As the great Renaissance scientist Johannes Kepler, the discoverer of the laws of planetary motion, put it, “Geometry is one and eternal, a reflection out of the mind of God. That mankind shares in it is one reason to call man the image of God.” In other words, the human mind, because it is the image of God, is able to understand the laws of the universe. It was the forceful demonstration of this proposition by Kepler, Galileo, and others that let loose the scientific revolution in the West.

Science, reason, morality based on individual conscience, human rights; this is the Western humanist heritage. Whether expressed in Hellenistic, Christian, deist, or purely naturalistic forms, it all drives toward the assertion of the fundamental dignity of the human. As such, it rejects human sacrifice and is ultimately incompatible with slavery, tyranny, ignorance, superstition, perpetual misery, and all other forms of oppression and degradation. It asserts that humanity is capable and worthy of progress.

This last idea—progress—is the youngest and proudest child of Western humanism. Born in the Renaissance, it has been the central motivating idea of our society for the past four centuries. As a civilizational project to better the world for posterity, its results have been spectacular, advancing the human condition in the material, medical, legal, social, moral, and intellectual realms to an extent that has exceeded the wildest dreams of its early utopian champions.

Yet now it is under attack. It is being said that the whole episode has been nothing but an enormous mistake, that in liberating ourselves we have destroyed the Earth. As influential Malthusians Paul Ehrlich and John Holdren put it in their 1971 book Global Ecology:

When a population of organisms grows in a finite environment, sooner or later it will encounter a resource limit. This phenomenon, described by ecologists as reaching the “carrying capacity” of the environment, applies to bacteria on a culture dish, to fruit flies in a jar of agar, and to buffalo on a prairie. It must also apply to man on this finite planet.

Note the last sentence: It must also apply to man on this finite planet. Case closed. The only thing left to decide is who gets death and who gets jail.

We need to refute this. The issue before the court is the fundamental nature of humankind. Are we destroyers or creators? Are we the enemies of life or the vanguard of life? Do we deserve to be free?

Ideas have consequences. Humanity today faces a choice between two very different sets of ideas, based on two very different visions of the future. On the one side stands the antihuman view, which, with complete disregard for its repeated prior refutations, continues to postulate a world of limited supplies, whose fixed constraints demand ever-tighter controls upon human aspirations. On the other side stand those who believe in the power of unfettered creativity to invent unbounded resources and so, rather than regret human freedom, demand it as our birthright. The contest between these two outlooks will determine our fate.

If the idea is accepted that the world's resources are fixed with only so much to go around, then each new life is unwelcome, each unregulated act or thought is a menace, every person is fundamentally the enemy of every other person, and each race or nation is the enemy of every other race or nation. The ultimate outcome of such a worldview can only be enforced stagnation, tyranny, war, and genocide. Only in a world of unlimited resources can all men be brothers.

On the other hand, if it is understood that unfettered creativity can open unbounded resources, then each new life is a gift, every race or nation is fundamentally the friend of every other race or nation, and the central purpose of government must not be to restrict human freedom but to defend and enhance it at all costs.

It is for this reason that we need urgently to open the space frontier. We must joyfully embrace the challenge of launching a new, dynamic, pioneering branch of human civilization on Mars—so that its optimistic, impossibility-defying spirit will continue to break barriers and point the way to the incredible plentitude of possibilities that urge us to write our daring, brilliant future among the vast reaches of the stars. We need to show for all to see in the most sensuous way possible what the great Italian Renaissance humanist Giordano Bruno boldly proclaimed: “There are no ends, limits, or walls that can bar us or ban us from the infinite multitude of things.”

Bruno was burned at the stake by the Inquisition for his daring, but fortunately others stepped up to carry the banner of reason, freedom, and dignity forward to victory in his day. So we must do in ours.

And that is why we must take on the challenge of space. For in doing so, we make the most forceful statement possible that we are living not at the end of history but at the beginning of history; that we believe in freedom and not regimentation, in progress and not stasis, in love rather than hate, in peace rather than war, in life rather than death, and in hope rather than despair.