CHAPTER 12

Sausage

When I was learning how to make sausage many years ago, I discovered an interesting fact: The United States produces and consumes more sausage than any other country in the world. This helps to explain why Americans have such a great interest in sausage making.

When I was learning how to make sausage many years ago, I discovered an interesting fact: The United States produces and consumes more sausage than any other country in the world. This helps to explain why Americans have such a great interest in sausage making.

Another thing that I discovered is that some of the books on sausage making do not cover the smoking of sausage, though they may cover other aspects of sausage making quite well. Furthermore, even if a book explains the smoking of sausage, it might not give clear information regarding the danger of contracting botulism by eating smoked sausages that were improperly cured. In the books that do discuss the curing of sausage, they often specify the old-fashioned potassium nitrate (saltpeter) curing agent instead of the modern, safer curing powders such as Prague Powder #1, Modern Cure, and Insta Cure #1. Consequently, for these various reasons, I felt that a chapter on sausage making should be included in this book. Such a chapter is required to explain how to safely cure and smoke sausage.

In order to cover these important subjects, we must begin with the fundamentals of sausage making. First, the basic tools and supplies will be explained. Next, I will describe the basic categories of sausages, and give you instructions on how to make several kinds of sausages in each of these categories.

By following the instructions in this chapter, you will be able to make some very serious, tasty, and wholesome sausages. If this sparks your interest in sausage making, please consult specialized books on the subject. You will find hundreds of recipes, including recipes for categories of sausages such as fermented sausages and dry cured sausages that are not covered in this book.

Before starting, let us explore the meaning of the word sausage. Sausage is usually defined as chopped or minced meat that is blended with salt and other seasonings. (The word sausage is related to salsicius, a Latin word that means “seasoned with salt.”) Sausage may also contain color fixers such as sodium nitrite or, in some cases, a blend of sodium nitrite and sodium nitrate. (Potassium nitrate—commonly known as saltpeter—was used in the past, and it is still used in some amateur sausage recipes.)

The meat can be the flesh of any animal, fowl, or fish. Some sausages may contain dairy products or even grains or vegetables such as rice or potatoes. The possible combinations are unlimited. Commercial processors use preservatives as well, and they use chemicals that help to stabilize the color. If homemade sausages are handled properly, such additives are not needed.

Equipment and Supplies

Some of the equipment and supplies you have assembled for food smoking can be used for sausage making. Most of the special equipment and supplies you will need are listed below. A good place to purchase many of these things is at a shop that specializes in butcher and sausage-making supplies. All of these items may be found on the Internet, as well. See appendix 5 for additional help in locating them.

MEAT

Meat is not a special supply item, but it is certainly the most important.

No matter what kind of meat you are using for sausage, it should be fresh. Ground meat will spoil faster than solid, so it is best to start with fresh solid meat to ensure a wholesome product.

Traditionally, sausage containing 25 percent fat and 75 percent lean has been considered the perfect ratio, but many people who make their own sausage prefer a healthier, leaner sausage.

Pork is the most commonly used meat for making sausage, and an economical cut that is variously called Boston butt, shoulder butt, or pork butt is most often used. Besides being economical, it is a very convenient cut to use because it contains about the perfect ratio of lean to fat. Any cut of pork can be used, so use the most economical. In this chapter, I will use the expression pork butt, but please understand this to refer to any cut of pork that contains about 25 percent fat—or whatever amount you prefer. If you are going to mix pork fat with some kind of lean meat, hard pork fat is the best kind of fat to use because it has a high melting point. Use a type of hard fat known as fatback whenever available.

If beef is used to make sausage, any cut may be used, but I will use the term beef chuck in this chapter. Beef chuck is economical, and it usually contains about the right amount of fat.

If wild game meat is used, it is best to trim and discard all the fat from the meat; very few people like the taste of wild game fat. To replace it, use enough pork fat—hard pork fat, if available—to bring the percentage of fat to the desired level.

MEAT CHOPPERS (MEAT GRINDERS OR MEAT MINCERS)

Meat choppers are also called meat grinders or meat mincers. All these terms refer to the same kind of hand-operated or electrically powered machine. I will use the terms interchangeably in this book.

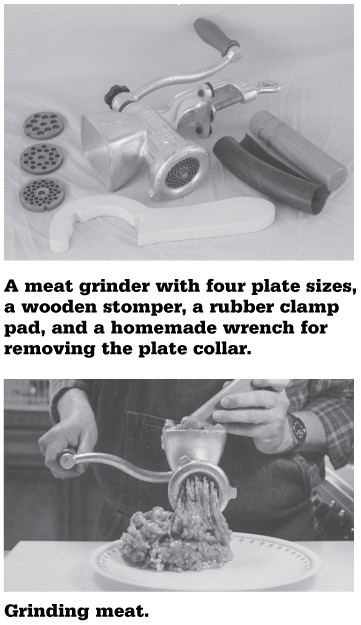

Initially, ground meats that can be bought at a food market can be used to make sausage. Eventually, however, you will need a meat chopper to process meats to suit your taste; for example, ground pork sold in grocery stores usually contains too much fat to make quality sausage. An old-fashioned (hand-operated) meat chopper made of tin-dipped cast iron will do the job very well. Either the size 8 or the slightly larger size 10 is adequate for home use. These meat choppers clamp on a table, a countertop, or on the breadboard that is built into most kitchen cabinets. If you buy a meat chopper that attaches to the countertop by suction cups, you will probably be disappointed; suction cups are inadequate to hold the machine in place. An electric meat chopper does the job a little faster, but it is not at all necessary unless you intend to make large quantities of sausage frequently.

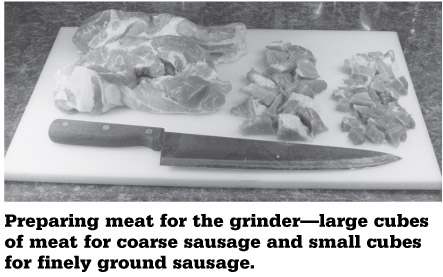

All meat choppers operate in the same way: Pieces of meat are put into the hopper, and a worm gear forces the meat into the holes in the plate. A four-bladed knife lies flat against the back of the plate, and it rotates to cut off the meat that has been forced into the holes. If the grinder is not chopping the meat properly, or chopping it too slowly, this may be due to the plate collar not being screwed down tightly, or due to something preventing the knife from lying flat against the plate.

The size of the holes in each plate determines the coarseness of the chopped meat. You should have three plates with the following hole sizes: 3⁄16 inch (4.8 mm), ¼ inch (6.4 mm), and ⅜ inch (9.5 mm). Additional plates with holes smaller or larger than these are useful, but not required.

SAUSAGE-STUFFING

TUBES AND SAUSAGE

STUFFERS

A sausage-stuffing tube is also called a funnel, a stuffing cone, or a horn. If large-diameter synthetic casings are used, a common funnel with a large mouth will do. Special stuffing tubes are required if you are going to use natural hog casings, sheep casings, or collagen casings. Some of these are designed to be handheld; they have the shape of a funnel, so the word funnel is most appropriate for them. However, handheld sausage funnels for hog, sheep, and small collagen casings are time consuming to use, and they are becoming increasingly harder to obtain.

Some tubes are designed to be attached to a meat grinder. Most electric and some hand-operated meat grinders come with one or more sizes of stuffing tubes. These sausage-stuffing tubes will do the job, but two people are required to stuff the sausages. One person must keep the hopper full of the sausage mixture and try to keep it packed firmly to reduce the number of air bubbles; the other tends the casing as it is being stuffed. Because two people are required, and because air bubbles in the sausages are more likely, using a stuffing tube that attaches to a meat grinder is not recommended.

I recommend the three-pound cast-iron sausage stuffer. It is called a three-pound stuffer because the manufacturers claim that it will hold three pounds of ground meat—it won’t, but that does not cause a problem. Such a stuffer is efficient, is reasonably priced, and can be operated easily by one person. In most cases, these stuffers are sold with an assortment of three diameters of stuffing tubes: ⅝ inch (16 mm), ¾ inch (19 mm), and 1 inch (25 mm). They will allow the stuffing of any size of sausage casing.

The feet of these cast-iron sausage stuffers have notches so that the stuffer can be mounted on a platform with bolts. Sausage stuffing is much easier if the stuffer is mounted on a board similar to the one in the photo. The board in the photo is 10 by 20 inches (25.5 x 51 cm), and it was cut from ¾-inch (2 cm) plywood.

- Left front: A homemade sausage pricker.

- Front: Three homemade tube plungers (for pushing meat out of the tube at the end of a sausage-stuffing session).

- Handle for the sausage stuffer.

- Small bottle brush (for cleaning the stuffer tubes).

- A homemade cone made of water putty. This is used for pushing out the meat that will remain in the tapered front section of the stuffer when the stuffing session is nearing completion.

- A homemade disk-shaped gasket made of dense, white foam rubber. This helps to prevent “backflow” around the pressure plate.

- Three diameters of sausage-stuffing tubes.

- Stuffer mounting platform. The feet of the stuffer can be attached to this board with four bolts.

The diameter of the pressure plate is a little less than internal diameter of the elbow-macaroni-shaped ground-meat hopper. The smaller diameter is necessary so the pressure plate can pass through the curved hopper cavity without binding. This smaller diameter of the pressure plate creates a minor problem, however: When the lever is pushed down, most of the sausage will flow out of the tube and into the casing as it should, but some will flow back around the edges of the pressure plate.

This backflow problem can be minimized or eliminated if a homemade gasket is employed. Cut a circular gasket from dense foam rubber; the diameter should be a little larger than the internal diameter of the hopper cavity. Wrap this gasket in plastic food wrap (to keep it clean), and place it between the sausage mixture and the pressure plate. The gasket will prevent almost all of the backflow.

Another minor problem with these stuffers is that the pressure plate will not push out all of the sausage. This is because the pressure plate will stop near the front of the stuffer at the point where the stuffer’s nose begins to taper toward the stuffing tube. About ⅓ pound (165 g) of sausage will remain in this conical cavity. However, most of the sausage that remains in the nose can be pushed out with a homemade cone such as the one shown in the photo on page 253.

To make this cone, a plastic funnel that had about the same degree of taper as the conical cavity was used as a mold. The bottom of the funnel was plugged with clay, and then a powder compound called water putty was mixed with water and poured into the funnel. (Durham’s is a popular brand of water putty.) After the water putty hardened into a cone, it was removed from the funnel, dried for about one week, and then painted with about four coats of clear polyurethane varnish. Such a cone made with water putty will be about as heavy and durable as oak. Water putty can be purchased at any hardware store, and the directions for use are on the package.

Wrap the cone in plastic food wrap before it is used; this helps to keep it clean, and it helps to prevent it from becoming jammed inside the stuffer cavity.

Two sheets of newspaper crumpled into a ball and placed in a plastic bag will perform the same function as a cone, and it will work almost as well.

SAUSAGE MOLDS AND CASINGS

Generic bulk sausage that is purchased in a grocery store is usually sold in a Styrofoam tray. However, a nationally known brand of bulk breakfast sausage is usually sold in a plastic ground-meat tube. This raw sausage can be sliced into patties by cutting through the tube at approximately 3/8-inch (10 mm) intervals.

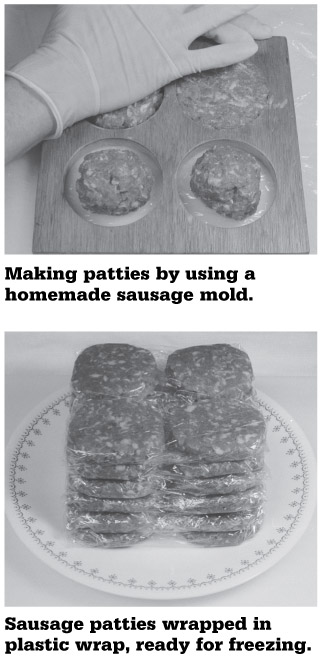

Similar ground-meat tubes (also called bags) can be purchased wherever sausage casings are sold, but making patties using a mold is a cheaper and better option. A metal ground-meat mold that will make one patty at a time can be purchased, but the homemade patty mold shown in the photograph on page 257 is better—it will make four patties at a time. The mold was cut from ⅜ inch (1 cm) plywood, and the diameter of each hole is about 2½ inches (6.3 cm). Because it is coated with polyurethane varnish, it will withstand washing in hot, soapy water for a lifetime. In fact, it will certainly last long enough for me to pass it along to my grandchildren. It is very easy to use.

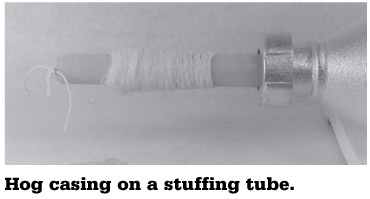

For stuffed sausage, the most commonly used casings are hog casings, sheep casings, collagen casings, and synthetic fibrous casings. When Rome ruled most of the Western world, the Romans used chicken neck skin as sausage casings.

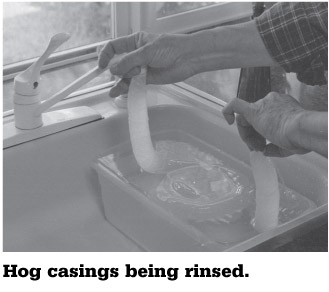

Hog casings are made from carefully cleaned small intestines, and they are normally sold in four sizes that range from about 1 inch (25 mm) to 1¾ inches (45 mm). They are, of course, edible. In this introduction to sausage making, the smallest size is suggested; it varies from about 1 to 1¼ inches (25 to 30 mm). For home use, it is best to purchase casings that have been packed in salt; such casings can be preserved for years under refrigeration. The casings are prepared for use by rinsing them very well with water, inside and out. After rinsing, they should be soaked in fresh water in the refrigerator overnight. This removes the remaining traces of salt and leaves the casings more tender, more slippery, and easier to use. Always rinse a little more casing than you think you will need. If some is left over, it can be resalted with noniodized salt and preserved.

Sometimes casings that are packed in salt are not available, and the casings offered are those that are packed in brine. These casings, also, are acceptable, and they will keep for years in the freezer if handled properly. If you buy such casings, I suggest that you divide the casings into about six parts, and place each part in a small plastic bag. Add some of the brine and a little noniodized salt to each bag; freeze all of the bags except the one you are currently using.

Natural sheep casings are smaller and more tender than hog casings. They are also about twice as expensive. Sheep casings packed in salt or brine are available, and they are used in the same way as hog casings. Sheep casings will not be used in this introduction to sausage making.

Collagen is a gelatin that is extracted from the bones, connective tissues, and hides of cattle. This gelatin is used to manufacture collagen casings. The casings are edible, and they are made in various sizes. The wall thickness varies with the intended use of the casing. For example, casings used for smoked sausage need to be strong, so they will have thicker walls. Some of these casings require refrigeration, but others do not. Because these casings are uniform, and because their use requires less labor than natural casings, they are widely used by commercial processors despite their slightly higher price. We will not use these casings for the products in this chapter, but keep them in mind—you may wish to use them in the future.

Synthetic fibrous casings are very useful for large-diameter snack sausages or lunchmeat sausages. These casings are not edible, but they are very strong, and they will not tear while they are being stuffed. Fibrous casings are available in diameters ranging from 1½ inches (38 mm) to over 4¾ inches (120 mm). If fibrous casings are used, it is best for the beginner to use casings not more than about 2½ inches (63 mm) in diameter and not more than 12 inches (30 cm) long. This size is easier to process, and the cooking time will be faster than for larger diameters. We will use this size for products in this chapter. To make them supple, synthetic fibrous casings are soaked in water for about 20 or 30 minutes before use.

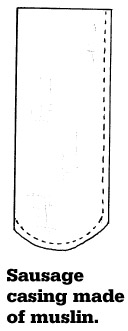

Finally, you may make casings of muslin. Such casings may be used in place of synthetic fibrous casings. Tear—do not cut—a strip of muslin 8 inches (13 cm) wide and about 12 inches (30 cm) long. (To the extent possible, the material should be torn rather than cut; tearing reduces the amount of cloth fibers that will get into the sausage.) Fold the strip in half, and sew it along the side and around one end. This will produce a casing with a diameter of about 2¼ inches (5.7 cm). If the material is new, it is best to launder it before it is used. This will remove any fabric conditioners that are present. Turn this closed-end tube inside out, wet it with vinegar, and stuff it with sausage. (The vinegar prevents the cloth from bonding to the sausage.)

HOW TO USE A HOMEMADE SAUSAGE MOLD

- Tear off about 18 inches (45 cm) of plastic food wrap, and spread it on the countertop. Place the homemade sausage mold in the middle of the food wrap.

- Place an egg-sized ball of bulk sausage in the middle of each of the four mold holes.

- Slap the top of each ball of bulk sausage repeatedly with the palm of your hand until the sausage fills the mold. Add or remove a small amount of sausage, if necessary.

- Lift one edge of the mold, and gently push the patties out of each of the mold holes. Let the patties fall back down on the food wrap.

- Remove the mold completely, and fold over the edges of the plastic food wrap—left, right, top, and bottom—to make an airtight package for the four patties. Place the package on a flat surface in the freezer.

HOG-RING PLIERS AND HOG RINGS

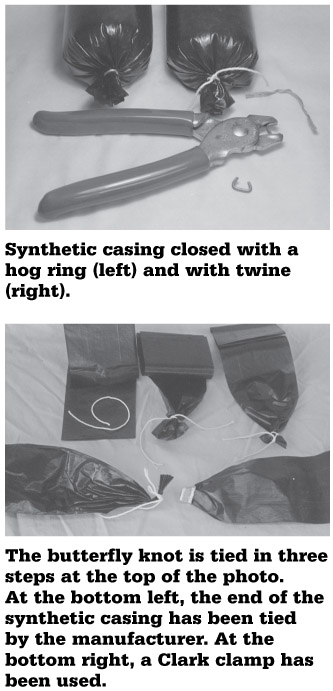

Hog rings may be used to close both the bottom and the top of fibrous casings, but they are most often used to close the top. They are easier and faster to use than twine, and they look professional. The spring-loaded pliers are easier to use, but they cost more than common hog-ring pliers. For 2½-inch-diameter (63 mm) casings, use the ⅜-inch (10 mm) hog rings. (If you wish to purchase these special hog rings and hog ring pliers, see appendix 5.)

If the casings are not closed on the bottom, common twine may be used to close them. However, a great deal of pressure is put on the bottom closure when the sausage is being stuffed. Consequently, if it is tied with twine, the very strong butterfly tie, shown in the photo, should be used. The top portion of the photograph demonstrates how to close the end of a synthetic casing in three steps:

- Cut a length of twine— about 5 inches (13 cm).

- Tie the end of the casing with a common square knot.

- Bring the ends of the twine around the bottom of the casing, and tie another square knot in such a way that the ends of the casing flare (butterfly) to the left and right.

Some casings are tied on the bottom with nylon twine by the manufacturer; such casings are easiest to use. (See the bottom left of the photo above.)

Also, an aluminum cap-like device called a Clark clamp can be used to close the end of a synthetic casing. First, the end of the casing is folded several times until it is small enough to fit inside the Clark clamp. Next, this folded end of the casing is inserted into the clamp, and the clamp is secured by squeezing it with pliers. (See the photograph.) Clark clamps can be purchased wherever sausage-making supplies are sold.

POWDERED SKIM MILK

Professional sausage makers and some advanced amateurs often use a product called soy protein concentrate. This helps to bind the sausage, retains the moisture, and makes the sausage plump. Powdered skim milk will do the same thing, and it is much easier to obtain. For 2½ pounds (1,150 g) of raw material, add to the seasonings ½ cup (120 ml) of powdered skim milk and ¼ cup (60 ml) of chilled water. Mix the powdered skim milk and water with the seasonings until the powdered milk has dissolved and the mixture is uniform. Add the ground meat and mix well.

CORN SYRUP

Some sausages taste better with a sweetener. Sugar can be used, but corn syrup will provide the same sweetening effect, and it will function as a binder as well. Professional sausage makers use powdered corn syrup solids, but this product is difficult to obtain, and it tends to cake and become as hard as a brick over time. Liquid corn syrup, however, can be found in any grocery store where pancake syrup is sold. There are two types, light and dark; light is recommended for sausage making. It is perfectly colorless like water.

Bulk Sausage

Three formulations for bulk sausage are given in this chapter, but you can easily find hundreds of bulk sausage recipes in books, in magazines, and on the Internet. For example, my favorite formula for breakfast sausage is presented in this chapter, but I have seen numerous formulations for American-style breakfast sausage in various books. None of the formulations is the same as mine, and most of them are different from one another. Obviously, it would be very easy to write a book restricted to the subject of bulk sausage alone.

All of the following bulk sausage formulations contain powdered skim milk, which in turn contains lactose (milk sugar). Because any kind of sugar makes sausage brown very fast, patties should be cooked over medium-low heat and turned frequently. The sausage patties are done when they become reddish brown on both sides.

Warren’s Country-Style

Bulk Breakfast Sausage

Below is my favorite formula for American-style bulk breakfast sausage. The use of poultry seasoning makes this unusual.

THE MEAT

Prepare 2½ lbs. (1,150 g) ground pork that contains about 20 percent fat. Mince the pork with a ¼-inch (6.4 mm) or 3⁄16-inch (4.8 mm) plate.

THE SEASONING

2 tsp. (10 ml) salt

1 tsp. (5 ml) poultry seasoning—packed in the spoon

1 tsp. (5 ml) rubbed sage—packed in the spoon

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) oregano, or marjoram

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) black pepper

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) red pepper

¼ cup (60 ml) water

½ cup (120 ml) powdered skim milk

- Grind the meat and refrigerate it. Mix the seasoning, powdered skim milk, and water in a large mixing bowl.

- Blend the meat and the seasoning well. Shape the mixture into ⅜inch-thick (10 mm) patties, and wrap them in plastic food wrap. Refrigerate the sausage that will be eaten within the next two days, and freeze the remainder.

Polish Kielbasa—

Bulk-Style Fresh Sausage

Kielbasa is a traditional Polish sausage. There are many varieties; each region of Poland has a different way of seasoning it. Most varieties are made with coarsely chopped pork.

This sausage may be frozen for two months, but if it is left unfrozen in the refrigerator for a few days, an unusual phenomenon takes place: When the sausage is cooked, the center remains pink, even though it is fully cooked. I believe that the garlic in the seasoning formula is responsible for this color fixing. All agricultural products contain nitrate compounds, and the nitrate in the garlic could slowly degrade to nitrite while it is in the refrigerator. This could cause the color fixing. To avoid this problem, thaw the sausage overnight and use it the next day. Better yet, thaw it in a microwave oven, and then fry it right away.

THE MEAT

Mince 2½ lbs. (1,150 g) pork butt with a ¼-inch (6.4 mm) plate.

THE SEASONING

2½ tsp. (12.5 ml) salt

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) granulated sugar

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) marjoram

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) garlic powder

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) black pepper

⅓ cup (80 ml) water

½ cup (120 ml) powdered skim milk

- Mix the seasonings in a large mixing bowl.

- Blend the meat and the seasonings well. Shape the mixture into patties that are about ⅜ inch (10 mm) thick, and wrap them in plastic food wrap. Freeze all patties that will not be eaten within one day.

Scandinavian-Style Sausage—

Bulk-Style Fresh Sausage

The use of potatoes or potato flour is traditional in some of the sausages made in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark. Certain elements of several Scandinavian sausages were combined to formulate the sausage below. This simple sausage is certain to be appreciated by meat-and-potatoes people.

THE MEAT

Mince the following meats with a 3⁄16-inch (4.8 mm) plate:

2 lbs. (910 g) pork butt

½ lb. (225 g) beef chuck

THE SEASONING

2 Tbsp. (30 ml) granulated onion, or onion powder

1½ tsp. (7.25 ml) salt

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) white pepper

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) allspice

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) granulated sugar

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) chicken bouillon powder, or chicken consommé powder

½ cup (120 ml) water

½ cup (120 ml) powdered skim milk

1 cup boiled and mashed potatoes, unseasoned, chilled

- Blend all the seasoning ingredients except the mashed potatoes, then add the potatoes and blend again.

- Blend the meat with the seasoning-and-potato mixture. Shape the blend into patties about ⅜ inch (10 mm) thick, and wrap them in plastic food wrap. This sausage is very perishable; freeze all patties that will not be eaten within one day.

Stuffed Fresh Sausage

In the world of sausage making, some expressions have a special meaning. The expression fresh sausage is one case in point. Fresh sausage means sausage that does not contain nitrites or nitrates. The opposite of fresh sausage is cured sausage. Sausage makers tend to use the word cured whenever nitrates or nitrites have been used. However, food smokers (not sausage makers) will often use the word cured even if only dry salt or common brine has been used. It is confusing, but we can’t change the way people use the English language. We have to live with it.

The bulk sausages described above are, therefore, kinds of fresh sausages. If it is stuffed in casings, it is still called fresh sausage, but some people prefer to call it stuffed fresh sausage. Below, we will learn how to make several kinds of stuffed fresh sausage.

STUFFING NATURAL CASINGS

Stuffing natural sausage casings is easy to do, but a few pointers should make the learning process go a little faster:

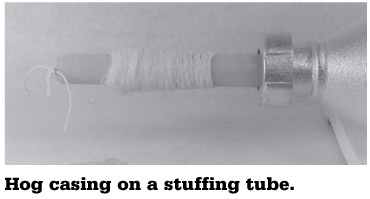

- Attach the proper size stuffing tube to the stuffer. Use a ¾-inch (20 mm) tube for hog casings, and a ½- or ⅝-inch (13 or 16 mm) tube for sheep casings. The main idea is that the casing should fit loosely on the tube, but not too loosely.

- Filling the stuffer half full with the seasoned sausage mixture will allow the pressure plate handle to provide greater leverage. Pack the mixture in the stuffer a little at a time, using your fist to remove the air pockets.

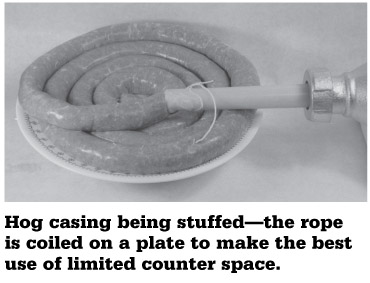

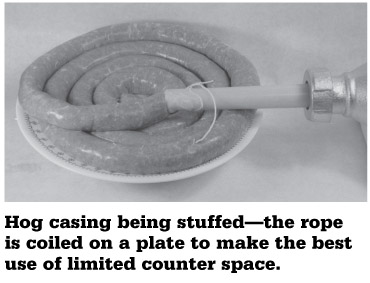

- Wet the entire length of the stuffing tube with water, and slide the wet casing onto the tube. Bunch the casing on the tube so that it looks something like a compressed accordion (see photo). Initially, the end of the casing should be at the end of the stuffing tube.

- Press down the lever handle on the stuffer so that a small amount of sausage begins to emerge from the tube. Slide about 1½ inches (4 cm) of casing off the end of the tube. Force all of the air out of the end of the casing, and tie a knot in it. Alternatively, close the end of the casing by using twine—I find that twine is faster, easier, and wastes less casing.

- If you are right-handed, you will probably be most comfortable if you operate the stuffer handle with your right hand. With the thumb and fingers of your left hand, slide the casing off the end of the tube as the sausage is being forced out. Keep your left hand cupped under the tube and toward the front; part of the palm should support the sausage casing as it is being filled. As you can see, your left hand will be very busy.

- When the sausage mixture is forced into the casing, the goal is for the stuffed casing to be uniform and rather firm—but not so firm that the casing ruptures when you are twisting the sausage to form links. If an air bubble appears in the casing at any time, prick it right away with a sausage pricker or a large needle.

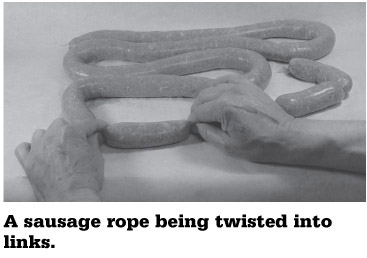

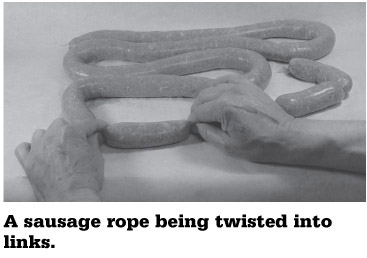

- Links can be made any length. Start from either end of the rope. To make 5-inch (13 cm) links, grab the sausage 5 inches from the end of the rope with one hand and 10 inches (26 cm) from the end of the rope with the other. Pinch the rope in these two places with your thumbs and index fingers, and then twist the link that lies between your hands four or five revolutions clockwise. Pinch the rope again in two places that are located 5 and 10 inches (13 and 26 cm), respectively, from the last twist. Twirl this new link counterclockwise. Continue making links until the other end of the rope is reached. It is best to use some kind of gauge to make sure that the links are the same size; something like a measuring stick, two pieces of masking tape stuck on the counter, or two marks on a sheet of paper will work well.

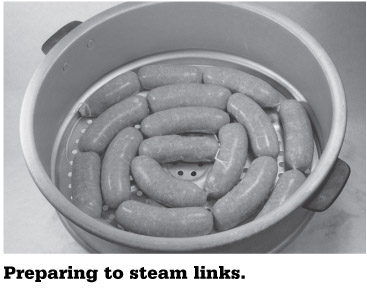

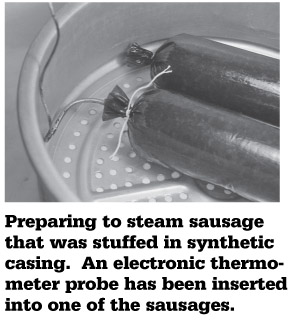

STEAMING SAUSAGE LINKS

When I make stuffed fresh sausage, I usually steam the sausages immediately after stuffing them. I often steam cured sausage, as well. If sausages are fully cooked by steaming—fresh sausages or cured sausages—the sausages are sterilized, the shelf life is longer, and they need only to be heated prior to serving; you might call them brown-and-serve sausages.

Professional sausage makers consider the sausage to be fully cooked when the internal temperature is between 152º F and 155º F (66.6º and 68.3º C). I steam them until the internal temperature is 160º F (71.1º C). However, if the sausage contains fowl, I steam until the internal temperature is 165º F (74º C). Instructions in this chapter often suggest steaming fresh sausages immediately after stuffing, but they may be refrigerated raw instead.

Of course, steamed sausages may be eaten immediately, but one of my favorite methods of preparing either raw sausages or sausages that have been steamed is to fry them in a covered skillet at medium-low heat until they have a brown stripe on both sides.

English Bangers—

Stuffed Fresh Sausage

This sausage is stuffed in hog casings, and it is very popular in the United Kingdom. A special feature of this sausage is the use of bread crumbs as one of the main ingredients. The bread crumbs retain moisture, and a significant amount of steam is generated in the sausage when it is cooked. The pressure generated by the steam is often enough to make the sausages rupture or explode; they are called bangers for this reason.

You may use the prepared, unseasoned bread crumbs available in all grocery stores in the United States or the coarse Japanese-style bread crumbs available in Asian food stores (known as panko); you can also make your own by raking dried bread with the tines of a fork. Depending on the kind and amount of bread crumbs you use, you may have to adjust the moisture content of the stuffing mixture.

You will note that powdered skim milk is not used in this formula. It is not required because the bread crumbs function to retain moisture and plump the sausage links. Pork broth is often used in bangers. However, I find that chicken consommé powder mixed with water is more convenient, and tastes just as good.

THE CASINGS

Prepare 7 feet (210 cm) of hog casings. Rinse the casings, and soak them in water overnight. Rinse again before using.

THE MEAT

Mince 2½ lbs. (1,150 g) pork butt with a ¼-inch (6.4 mm) plate. Chill the meat while preparing the seasoning.

OTHER INGREDIENTS AND SEASONING

1½ tsp. (7.5 ml) chicken consommé powder

1 tsp. (5 ml) salt

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) finely ground black pepper

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) sage—packed in the spoon

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) ginger powder

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) mace

¾ cup (180 ml) dry bread crumbs, not packed in the cup

½ cup (120 ml) cold water

- Mix the seasonings and other ingredients well in a large mixing bowl, and then blend in the meat until the whole mixture is uniform.

- Stuff the sausage. Make 5-inch (13 cm) links.

- Steam the links until the internal temperature is 160º F (71.1º C).

- Refrigerate the amount of sausage that will be used within one day. Freeze the remaining links.

Carl’s Italian Sausage—

Stuffed Fresh Sausage

A friend of Italian ancestry helped me tailor this sausage so that it closely matched the flavor of the sausage that he ate so often as a child. Carl Preciso was raised on a farm near the Columbia River in northern Oregon, and his grandfather, a farmer who was born in northern Italy, raised hogs on this farm. Whenever a hog was butchered, Grandpa made sausage of the type presented below.

The following is the mild version that is popular in northern Italy; it is also called sweet Italian sausage. To make the hot type, add more cayenne and, if you like, more paprika.

This sausage is traditionally stuffed into hog casings, but it can also be processed as bulk sausage and made into patties or used as a pizza topping.

THE CASINGS

Prepare 7 feet (210 cm) of hog casings. Rinse the casings, and soak them in water overnight. Rinse the casings again before using.

THE MEAT

Mince 2½ lbs. (1,150 g) pork butt with a ¼-inch (6.4 mm) plate. Chill the meat while preparing the seasoning.

OTHER INGREDIENTS AND SEASONING

2¼ tsp. (11.25 ml) salt

2 tsp. (10 ml) coarsely ground black pepper

2 tsp. (10 ml) coriander

2 tsp. (10 ml) cracked anise seeds

2 tsp. (10 ml) cracked or powdered fennel seeds

1 tsp. (5 ml) garlic powder

1½ tsp. (7.5 ml) paprika

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) cayenne

¾ tsp. (3.75 ml) thyme powder

⅛ tsp. (0.6 ml) bay leaf powder

¼ cup (60 ml) lemon juice

3 Tbsp. (45 ml) light corn syrup

½ cup (120 ml) powdered skim milk

¼ cup (60 ml) cold water

- Mix the seasonings and other ingredients well in a large mixing bowl, and then blend the seasonings with the meat.

- Stuff the sausage, and make 5-inch (13 cm) links.

- Steam the links until the internal temperature is 160º F (71º C). Alternatively, do not steam the links, and proceed to the next step.

- Refrigerate the number of steamed or raw links that will be used within one day. Freeze the remaining links.

Sometimes Italian sausage is browned in a frying pan, then a little red wine is added; the sausage is covered and steamed in the wine until fully cooked. This is one of Carl’s favorite methods of preparation.

Bockwurst—Stuffed Fresh Sausage

To me, this light-colored sausage is elegant and delicate. In Germany, however, bockwurst is considered a two-fisted beer drinker’s sausage. It is commonly eaten while drinking a strong, dark beer called bock beer—hence the name bockwurst. In some parts of the United States, bockwurst is also known as white sausage because of its light color. The formula is complex, but the numerous and unusual ingredients complement each other very well. It is one of my favorite sausages, and I make it several times during the spring when wild chives appear in my backyard.

THE CASINGS

Prepare 7 feet (210 cm) of hog casings. Rinse the casings, and soak them in water overnight. Rinse the casings again before using.

THE MEAT

Grind the following meats with a ⅜-inch (9.5 mm) or smaller plate. Chill

the meat while preparing the seasoning.

1¾ lbs. (800 g) fatty pork butt

¾ lb. (350 g) chicken breast, or veal (veal is traditional)

OTHER INGREDIENTS AND SEASONING

¼ cup (60 ml) fresh milk

2 tsp. (10 ml) salt

¾ tsp. (3.75 ml) finely ground white pepper

1 Tbsp. (15 ml) onion powder

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) ground celery seeds

1 tsp. (5 ml) chopped dehydrated parsley

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) mace

1 Tbsp. (15 ml) lemon juice

1 Tbsp. (15 ml) light corn syrup

¼ cup minced green onions, or chives

2 eggs

½ cup (120 ml) powdered skim milk

- Except for the meat, mix the seasonings and other ingredients well in a large mixing bowl. Add the ground meat, and knead the mixture at least three minutes until it is uniform.

- Stuff the sausage, and make the rope into 5-inch (13 cm) links.

- Steam the links until the internal temperature is 160º F (71º C)—or to 165º F (74º C) if you used chicken breast. Spray the sausage with cold water. Refrigerate, uncovered, until chilled. Package the sausage in plastic bags, and freeze the portion that will not be consumed within two days. Bockwurst is traditionally eaten with mild mustard.

Onion Sausage—

Stuffed Fresh Sausage

It is difficult to believe that a sausage so simple is so tasty. If freshly minced onion is used, use ¼ cup (60 ml), and reduce the ice water in the formula to 3 tablespoons (45 ml).

THE CASINGS

Prepare 7 feet (210 cm) of hog casings. Rinse the casings, and soak them in water overnight. Rinse them again before stuffing.

THE MEAT

Use 2½ lbs. (1,150 g) pork butt. Separate the lean meat from the fat. Grind the lean meat with a ¼-inch (6.4 mm) plate, and grind the fat with a 3⁄16-inch (4.8 mm) plate.

OTHER INGREDIENTS AND SEASONING

1 Tbsp. (15 ml) minced dehydrated onion

⅓ cup (80 ml) ice water

2½ tsp. (12.5 ml) salt

2 tsp. (10 ml) light corn syrup

¾ tsp. (3.75 ml) ground black pepper

¾ tsp. (3.75 ml) marjoram

½ cup (120 ml) powdered skim milk

- Mix all the ingredients except the meat in a large mixing bowl. Add the meat, and knead until the sausage is uniform.

- Stuff the sausage, and make 6-inch (15 cm) links.

- Steam the links until the internal temperature is 160º F (71º C). Spray the sausages with cold water. Refrigerate, uncovered, until chilled. Package the stuffed sausages in plastic bags. Freeze those that will not be eaten within two days.

Boudin-Style Sausage—

Stuffed Fresh Sausage

Several distinctly different Cajun sausages use the word boudin in the name. The original recipe for this sausage called for pork liver in addition to pork. However, my brother omitted the pork liver and made some other changes in the method of preparation. The result is a product that is often eaten by both his family and mine. It is certainly the most unusual sausage I have ever made. In addition to meat, it contains vegetables and rice. It is truly a meal in one.

THE CASINGS

Prepare 10 feet (300 cm) of hog casings. Rinse the casings, and soak them in water overnight. Rinse again the next morning.

THE MEAT

Prepare 2½ lbs. (1,150 g) minced pork butt. Use a ¼-inch (6.4 mm) plate.

OTHER INGREDIENTS AND SEASONING

6 cups (1,500 ml) cooked rice, medium grain preferred, cooled

¾ cup (180 ml) finely chopped onions

¾ cup (180 ml) finely chopped parsley

¾ cup (180 ml) chopped green onions

⅓ cup (80 ml) finely chopped green bell pepper

⅓ cup (80 ml) finely chopped celery

4 tsp. (20 ml) salt

1 tsp. (5 ml) minced garlic

1 tsp. (5 ml) black pepper

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) cayenne

- Except for the meat, mix the seasonings and all other ingredients in a large plastic or stainless-steel container. Next, add the meat and mix again.

- Stuff the sausage. Make 6-inch (15 cm) links. Put the sausage links in plastic bags, expelling as much air as possible. Freeze or refrigerate immediately; this sausage is very perishable.

- To cook, steam the thawed sausage until it is plump, firm, and fully cooked. If you wish, you may use a baby-dial or electronic thermometer to measure the internal temperature, which must be 160ºF (71ºC), minimum.

Cured Sausage and Smoked Sausage

As mentioned previously, cured sausage is fresh sausage with the addition of Prague Powder #1 or some other brand of curing agent that contains sodium nitrite or a blend of sodium nitrite and sodium nitrate. (In this book, curing powder that contains 6.25 percent sodium nitrite is used exclusively.) The addition of a very small amount of a curing agent makes three big differences:

- If the meat in the sausage is a red meat such as beef, pork, or dark bird meat, the sausage will be pink or red after it is cooked.

- In addition to the attractive color, the use of the curing compound will impart a different and appealing taste.

- If the sausage is to be smoked, it can be smoked safely, without fear of botulism.

The addition of Prague Powder #1 to achieve color fixing and to cause a taste change is clearly a matter of personal preference. However, smoking sausage without the proper use of a curing compound is akin to playing Russian roulette. The temperature and time involved in smoking, together with the potentially oxygen-free condition at the center of the sausage, makes botulin formation possible. Just ½ teaspoon (2.5 ml) of Prague Powder #1 per 2½ pounds (1,150 g) of meat will positively prevent botulism. How much sodium nitrite is in that much Prague Powder #1? Well, Prague Powder #1 is composed of 16 parts salt to 1 part sodium nitrite. So, divide ½ teaspoon (or 2.5 ml) by 16. Life insurance is provided by about 1⁄32 teaspoon (0.156 ml) of sodium nitrite. Life insurance will never get cheaper than that.

Cured and stuffed sausage is often allowed to set in the refrigerator overnight before it is cooked or smoked. This is especially true for coarsely ground sausage. This resting time in the refrigerator allows the curing powder to penetrate the individual bits of meat thoroughly. However, if all of the meat is finely ground, penetration is very fast, and a resting time in the refrigerator of an hour or so is adequate.

Vienna Sausage—

Cured, Stuffed, Not Smoked

You may have heard of Vienna sausage. If you are an American, you may have sampled the tiny Vienna sausages that are sold in a small can. Many of the ingredients in the formula below are the same as those in the canned variety, but the finished product will be different. You should not expect the same taste and texture as the canned variety, but you should expect that it will be something very good to eat. The product we will make will be the real thing: Vienna sausage as it is made in Europe. In Europe—to the best of my knowledge—they do not put the Vienna sausage in cans.

Vienna sausage is a cured sausage, but it is not normally smoked. However, it does have Prague Powder #1 in the formula, so it can be smoked, if you wish.

THE CASINGS

Prepare 7 feet (210 cm) of hog casings. Rinse the casings, and soak them in water overnight. Rinse them again before stuffing.

THE MEAT

1½ lbs. (680 g) fatty pork

½ lb. (225 g) lean beef

½ lb. (225 g) lean veal (traditional), or chicken (either white or dark meat)

Mince the meats with a 3⁄16-inch (4.8 mm) or smaller plate. It would be best to mince the meats two times; mincing twice provides a finely textured sausage. Chill the meat between each grinding. Blend the pork, beef, and veal (or chicken) and refrigerate.

OTHER INGREDIENTS AND SEASONING

4 tsp. (20 ml) finely minced onions

1 Tbsp. (15 ml) flour

2 tsp. (10 ml) salt

1 tsp. (5 ml) coriander

¾ tsp. (3.75 ml) paprika

¾ tsp. (3.75 ml) sugar

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) Prague Powder #1

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) cayenne

⅛ tsp. (0.6 ml) mace powder

¼ cup (60 ml) cold water

½ cup (120 ml) powdered skim milk

- Mix the seasonings and other ingredients well in a large mixing bowl, then add the meat and blend well.

- Stuff the sausage.

- To ensure migration of the curing agent and seasonings, let the sausage rest at least one hour in the refrigerator.

- Steam the links until the internal temperature reaches 160º F (71º C). However, if chicken was used in place of veal, steam to an internal temperature of 165º F (74º C). Spray with cold water. Refrigerate, uncovered, until chilled. Package the sausages in plastic bags, and freeze the portion that will not be consumed within two days.

Old-Fashioned Frankfurters—

Cured, Stuffed, and Smoked

The commercially produced frankfurter (aka wiener, frank, hot dog, or frankforter) that we know today is prepared with emulsified meat. This permits the processors to use meats that we would normally not use: beef tripe, pork snouts, chicken skin, and so forth. Of course, these meats are considered fit for human consumption, but many people do not want to eat scrap parts.

It is easy for us to use higher-quality meats, but troublesome for us to emulsify the meat even if we use the best-quality food processor. To be sure, the original frankfurter made in Frankfort, Germany, was not made with emulsified meat; meat emulsifiers did not exist at that time. It is with this fact in mind that the words old-fashioned are used to name this product, which is much closer to the original frankfurters than to the kind sold in grocery stores today.

THE CASINGS

Prepare 7 feet (210 cm) of hog casing; rinse thoroughly. Soak in water, in the refrigerator, overnight. Rinse again before using.

THE MEAT

Grind 1½ lbs. (680 g) pork butt and 1 lb. (450 g) beef chuck with a 3/16inch (4.8 mm) plate—or use a plate with smaller holes, if available. If the meat is ground twice, it will become a little finer the second time. Chill the meat thoroughly.

THE SEASONING

2 tsp. (10 ml) salt

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) Prague Powder #1 1½ tsp. (7.5 ml) ground coriander

1 tsp. (5 ml) onion powder

1 tsp. (5 ml) finely ground black pepper

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) ground mustard seeds

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) garlic powder

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) marjoram

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) mace

1 large egg, well beaten

⅓ cup (80 ml) water

½ cup (120 ml) powdered skim milk

- Mix the seasonings, water, and skim milk in a large stainless-steel mixing bowl until they are thoroughly blended and the powdered milk has dissolved.

- Add the meat and mix well.

- Stuff the sausage in hog casings, and twist the sausage rope into links.

- Refrigerate at least one hour—overnight is better.

- Continue processing by using one of the three options described below. (Frankfurters are traditionally smoked.)

OPTION 1—STEAMING THE FRANKFURTERS—NO SMOKE

Steam the links until the internal temperature reaches 160º F (71º C). Eat immediately, or refrigerate uncovered. After the sausage is chilled, package it in plastic bags. Freeze the links that will not be consumed within two days.

OPTION 2—HOT SMOKED

If you wish to hot smoke the frankfurters, hang the raw links in a 130º F (55º C) smoker until the outside is dry to the touch (this will require at least 30 minutes). Make sure that the damper is fully open. Raise the temperature gradually to 165º F (75º C). Close the damper most of the way in order to reduce the airflow and, thereby, reduce dehydration. Hot smoke at this temperature until the internal temperature is 160º F (71º C). Remove the links from the smoker, and spray them with cold water until the internal temperature is below 110º F (43º C). Hang at room temperature for about 30 minutes. Refrigerate overnight before eating; this allows the smoke flavor to mellow.

OPTION 3—SMOKING AND STEAM COOKING

Steam cooking will result in less shrinkage than cooking in the smoker. Follow the directions for hot smoking (above), but remove the links from the smoker when the internal temperature is about 135º F (57º C). Steam the sausage until the internal temperature is 160º F (71º C). Spray with cold water, hang at room temperature for about 30 minutes, and refrigerate.

Polish Kielbasa—

Cured, Stuffed, and Smoked

The Polish kielbasa presented below differs a little from the bulk sausage kielbasa described earlier in this chapter. The seasoning is the same, but ½ teaspoon (2.5 ml) of Prague Powder #1 will be added. This curing powder will cause the kielbasa to become pink when it is cooked, and it will impart a little different flavor. Most importantly, because Prague Powder #1 is used, the sausage can be smoked and eaten without risk of botulism.

THE CASINGS

Prepare 7 feet (210 cm) of hog casing; rinse, and then soak in water, in the refrigerator, overnight. Rinse again before stuffing the casing.

THE MEAT

Grind 2½ lbs. (1,150 g) pork butt with a ¼-inch (6.4 mm) plate.

THE SEASONING

2½ tsp. (12.5 ml) salt

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) Prague Powder #1

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) granulated sugar

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) marjoram

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) garlic powder

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) black pepper

⅓ cup (80 ml) water

½ cup (120 ml) powdered skim milk

- Mix the seasonings, water, and skim milk in a large stainless-steel mixing bowl until they are thoroughly blended and the powdered milk has dissolved.

- Add the meat and mix well.

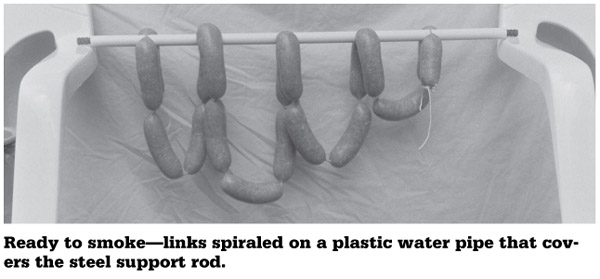

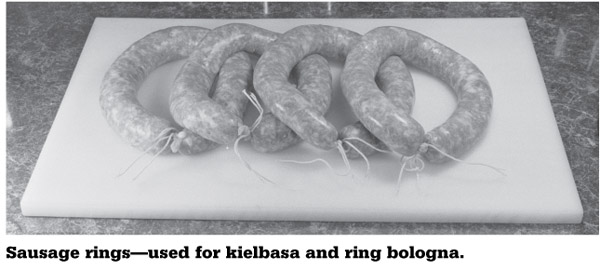

- Stuff the sausage in hog casings, and twist the sausage rope into links. Alternatively, tie the rope into four rings. Each ring will have a circumference a little greater than 1½ feet (45 cm).

COOKING AND SMOKING

Continue processing the sausage by following Option 1, 2, or 3 for making old-fashioned frankfurters.

German Bologna—

Cured, Stuffed, and Smoked

The commercially produced bologna luncheon meat that is sold here in the United States is, in my opinion, almost inedible. However, this homemade bologna is delicious. The taste, texture, and appearance are completely different from what is offered in supermarkets. Furthermore, we can be sure that this product does not contain any mystery meat such as pig snouts or cow navels.

THE CASINGS

Soak fibrous casings in water for 30 minutes prior to using. If you are using 2½-inch-diameter (6.4 cm) casings that are about 12 inches (30 cm) long, two of them will be required.

THE MEAT

Grind 1½ lbs. (680 g) beef chuck and 1 lb. (450 g) pork butt with a 3⁄16inch (4.8 mm) plate—use a plate with smaller holes, if available. Pass the meat through the grinder twice if you want it to be finer. Chill the meat thoroughly.

THE SEASONING

2 tsp. (10 ml) salt

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) Prague Powder #1

1 tsp. (5 ml) finely ground black pepper

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) ground mustard seeds

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) ground celery seeds

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) garlic powder

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) coriander

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) nutmeg

1 Tbsp. (15 ml) light corn syrup

¼ cup (60 ml) water

½ cup (120 ml) powdered skim milk

- Mix the seasonings, water, and powdered milk in a large bowl until the ingredients are uniform.

- Add the meat to the seasoning mixture. Blend it until it is uniform.

- Stuff the sausage into fibrous casings. Insert the cable probe of an electronic thermometer in the open end of one of the sausages, and close the casing around the probe with butcher’s twine.

- Refrigerate the stuffed sausages for a minimum of one hour; overnight is better.

SMOKING

Remove the sausage from the refrigerator, and place it in a smoker that has been heated to 150º F (65º C). Maintain this temperature with no smoke until the casing is dry to the touch. Raise the temperature to 165º F (75º C), and smoke the sausage for three to six hours.

COOKING—OPTION 1

After smoking, wrap each sausage in plastic food wrap, and then place each sausage in a plastic bag. Cook in 165º F (75º C) water until the internal temperature is 160º F (71º C). (See Hot Water Cooking in chapter 8, page 140.)

COOKING—OPTION 2

After smoking, wrap each sausage in plastic food wrap (optional), and then steam them until the internal temperature is 160º F (71º C).

COOLING

As soon as the hot water cooking or steam cooking is finished, chill the sausage in cold water until the internal temperature drops below 100º F (38º C). Refrigerate overnight before using.

Minced-Ham Lunchmeat—

Cured, Smoked

Many kinds of lunchmeats are actually sausages. Minced ham or pressed ham is one such product, and it is widely sold in grocery stores. The commercial product looks very good, but the flavor offers little more than salty pork. The following product will look similar to its commercial counterparts, but it contains the flavor they lack.

THE CASINGS

Fibrous casings about 2½ inch (6.4 cm) in diameter are used for this sausage. Two casings that are about 12 inches (30 cm) long will be required. Soak the casings in water for 30 minutes before stuffing.

THE MEAT

Use 2½ lbs. (1,150 g) pork butt. Separate the lean meat from the fat. Mince the lean meat with a ¼-inch (6.4 mm) plate, and the fat with a 3⁄16-inch (4.8 mm) plate. Combine the lean meat and the fat. Refrigerate the meat while you prepare the curing mixture.

OTHER INGREDIENTS AND SEASONING

2 tsp. (10 ml) salt

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) Prague Powder #1

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) white pepper

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) onion powder

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) garlic powder

4 tsp. (20 ml) maple syrup, or 1 Tbsp. (15 ml) honey

¼ cup (60 ml) water

½ cup (120 ml) powdered skim milk

- Mix the seasonings, water, and powdered milk in a large bowl until the ingredients are uniform.

- Add the meat to the seasoning mixture and blend well.

- Stuff the mixture into fibrous casings. Insert the cable probe of an electronic thermometer in the top of one of the sausages, and close the casing around the probe with butcher’s twine.

- Refrigerate the stuffed sausages overnight.

- Smoke and cook the minced ham by follow the instructions given previously for German bologna.

Salami—Cured, Stuffed, and Smoked

There are many kinds of salami. Most kinds are dry cured for many weeks, and they are neither cooked nor smoked. (In sausage maker’s jargon, dry curing has a special meaning: to dry raw sausage under controlled temperature conditions until the sausage weight has been reduced by a certain percent.)

This product contains ingredients that are common in salamis, but the processing is more like that of bologna; it is not dry cured, and it is fully cooked.

THE CASINGS

Soak fibrous casings in water for 30 minutes prior to using. Two casings will be required if they are 2½ inches (6.4 cm) in diameter and 12 inches (30 cm) long.

THE MEAT

Grind 1½ lbs. (680 g) beef chuck and 1 lb. (450 g) pork butt with a 3⁄16inch (4.8 mm) plate.

THE SEASONING

2 tsp. (10 ml) salt

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) Prague Powder #1

2 tsp. (10 ml) cracked black peppercorns

1 tsp. (5 ml) paprika

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) ground black pepper

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) onion powder

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) garlic powder

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) nutmeg

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) allspice

⅛ tsp. (0.625 ml) cayenne

2 Tbsp. (30 ml) sherry (optional, but recommended)

1 Tbsp. (15 ml) light corn syrup

¼ cup (60 ml) water

½ cup (120 ml) powdered skim milk

- Mix the seasonings, water, and the powdered milk in a large bowl until the ingredients are perfectly blended.

- Add the meat to the seasoning mixture and mix thoroughly.

- Stuff the sausage mixture into the fibrous casings. Insert the cable probe of an electronic thermometer in the open end of one of the sausages. Close the casing around the probe with butcher’s twine.

- Refrigerate the salami overnight.

SMOKING AND COOKING

Follow the smoking and cooking suggestions given previously for German bologna.

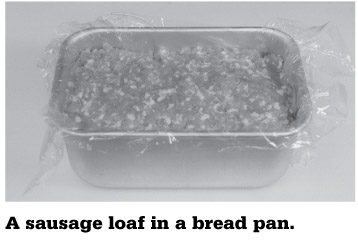

Sausage Loaf (Lunchmeat Loaf)

Sausage need not be made into patties or stuffed into casings—a common bread-baking pan can be used to mold and process the sausage. The finished product will be a loaf that can be sliced into delicious and economical luncheon meat.

Old-Fashioned Loaf—

Cured, Not Smoked

When I was young (and that was awhile ago), this product could be found in all of the large grocery stores, but I have not seen it in recent years. It was not as popular as pressed ham, for example, but it was a good lunchmeat when made with quality ingredients.

THE MEAT

Use a 3⁄16-inch (4.8 mm) plate to grind 1¾ lbs. (800 g) pork butt and ¾ lb. (350 g) beef chuck. Refrigerate.

THE SEASONING

¼ cup (60 ml) ice water

½ cup (120 ml) powdered skim milk

2 Tbsp. (30 ml) light corn syrup

1 Tbsp. (15 ml) onion powder

2 tsp. (10 ml) salt

¾ tsp. (3.75 ml) white pepper

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) Prague Powder #1

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) ground celery seeds

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) ground coriander

- Mix the seasonings, water, and the powdered milk in a large bowl until the ingredients are well blended.

- Add the minced pork and beef to the seasoning mixture. Knead the mixture about three minutes or until it is uniform.

- Line a loaf pan with plastic food wrap, and pack the mixture into the pan. Cover with plastic food wrap.

- Refrigerate the sausage overnight to harden it and make it easier to handle.

- Remove the sausage from the loaf pan by lifting the plastic wrap that was used to line the pan. Wrap the loaf with plastic food wrap, and insert the probe of an electronic thermometer into the center. (Stick the probe through the plastic wrap.) Steam the loaf until the internal temperature is 160º F (71º C).

- Remove the plastic food wrap and refrigerate immediately, uncovered. The next morning, the loaf may be sliced and wrapped.

Liver and Onion Loaf—

Cured, Optionally Smoked

Liver is an acquired taste, but it is well liked by those who have acquired the taste. Unfortunately, liver is very high in cholesterol, so many of us have been forced to cut down. This liver and onion loaf is a reasonable compromise: The 20 percent liver content provides a liver flavor, and the cholesterol level is acceptable for most people.

The directions below are for molding this product into a loaf, and then steaming it. However, if you wish, you could stuff it into fibrous casings, smoke it, and cook it like German bologna. Alternatively, it could be stuffed into hog casings and processed like frankfurters.

THE MEAT

Mince the following meats with a 3⁄16-inch (4.8 mm) plate:

½ lb. (225 g) beef chuck

1½ lbs. (680 g) pork butt

½ lb. (225 g) liver (any kind of liver may be used)

OTHER INGREDIENTS AND SEASONING

¼ cup (60 ml) ice water

½ cup (120 ml) powdered skim milk

1 small onion, about 2 inches (5 cm) in diameter, minced

2 Tbsp. (30 ml) light corn syrup

2 tsp. (10 ml) salt

1½ tsp. (7.25 ml) black pepper

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) Prague Powder #1

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) marjoram

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) ground mustard

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) ground nutmeg

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) ground ginger

Process this product in the same way as old-fashioned loaf.

Pastrami Sausage—Cured, Smoked

After successfully making several kinds of tasty luncheon meats, I realized that I had never made a luncheon meat with 100 percent beef. I have never heard of a product called pastrami sausage, but I thought that a beef-based product seasoned like pastrami would be very good; I was correct. The seasoning for this product is based on the seasoning for pastrami in chapter 9, page 173.

THE CASINGS

Either a bread-loaf pan or fibrous casings can be used for this sausage. If fibrous casings are used, soak them in water for 30 minutes before stuffing. See the processing options below.

THE MEAT

Use 2½ lbs. (1,150 g) fatty ground chuck. You could also use 2 lbs. (900 g) lean beef and ½ lb. (225 g) pork fat if you have only lean beef on hand. Mince the meat with a 3⁄16-inch (4.8 mm) plate. Refrigerate.

Other options for the raw material would be venison, bear, elk, or moose. Wild game meat that has been trimmed of all fat and mixed with an equal amount of fatty pork would make an excellent product. Alternatively, rather than using 50 percent fatty pork, 75 percent well-trimmed game and 25 percent pure pork fat could be used.

OTHER INGREDIENTS AND SEASONING

2 tsp. (10 ml) salt

2 tsp. (10 ml) light corn syrup 2 tsp. (10 ml) black peppercorns, cracked

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) Prague Powder #1

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) onion powder

½ tsp. (2.5 ml) garlic powder

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) cayenne

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) paprika

¼ tsp. (1.25 ml) oregano

⅛ tsp. (0.625 ml) allspice

⅛ tsp. (0.625 ml) ginger

¼ cup (60 ml) water

½ cup (120 ml) powdered skim milk

- Mix the seasoning, water, and the powdered skim milk in a large bowl until the ingredients are uniform.

- Add the meat to the seasoning mixture. Knead it until it is well blended.

- If fibrous casings will be used, stuff the mixture into the casings. Insert the cable probe of an electronic thermometer in the top of one of the sausages, and close the casing around the probe with butcher’s twine.

- If the sausage will be made into a loaf, line a loaf pan with plastic food wrap, and pack the mixture into the pan. Cover with plastic food wrap. (See the sausage loaf earlier in this chapter.)

- Refrigerate the sausage for a few hours, or overnight, to allow the curing agent to migrate to the center of each particle of meat.

Because pastrami is a smoked product, it is logical that this sausage should also be smoked. If you intend to smoke the sausage, note that different procedures are used for smoking sausage in fibrous casings and for smoking sausage that was formed in a loaf pan. If you do not intend to smoke the sausage, proceed to the instructions for cooking.

SMOKING THE SAUSAGE IN FIBROUS CASING (OPTIONAL)

Remove the stuffed casings from the refrigerator, and place them in a smoker that has been heated to 150º F (65º C). Maintain this temperature with no smoke until the casings are dry to the touch. Raise the temperature to 165º F (75º C), and smoke for three to six hours. Cook the sausage according to the instructions below.

SMOKING THE PASTRAMI LOAF (OPTIONAL)

Remove the loaf from the loaf pan by lifting the plastic food wrap liner. Put the loaf on a piece of parchment paper that has been perforated with many small holes. Dry the loaf in the smoker at less than 120º F (49º C). Blot the sausage with a paper towel from time to time while it is drying. Raise the temperature to about 150º F (65º C), and smoke for three to six hours. Cook the sausage according to the instructions below.

COOKING SAUSAGE STUFFED IN FIBROUS CASING

Wrap each sausage in plastic food wrap (optional). Twist the ends of the food wrap, securing them with a wire bread-bag tie. Steam the sausages until the internal temperature is 160º F (71º C).

COOKING A PASTRAMI LOAF

These instructions for cooking apply to either a smoked or an unsmoked loaf.

Wrap the loaf with plastic food wrap. Insert the probe of an electronic thermometer into the center; you may pierce the plastic wrap with the probe. Steam the loaf until the internal temperature is 160º F (71º C).

COOLING

If the sausage was stuffed in casing, chill it in cold water as soon as the cooking is finished. Continue chilling until the internal temperature drops below 100º F (38º C). Refrigerate overnight before using.

If the sausage was formed into a loaf, refrigerate the loaf overnight, uncovered, as soon as the cooking is finished.

When I was learning how to make sausage many years ago, I discovered an interesting fact: The United States produces and consumes more sausage than any other country in the world. This helps to explain why Americans have such a great interest in sausage making.

When I was learning how to make sausage many years ago, I discovered an interesting fact: The United States produces and consumes more sausage than any other country in the world. This helps to explain why Americans have such a great interest in sausage making.