A-Frame Legacy

Deering, New Hampshire

The roots of this humble abode are what A-frame dreams are made of. Long before she was born, Sarah’s grandparents desired a weekend getaway to escape the beach crowds that would descend upon the South Shore every summer. In search of land on which to build a cabin, her grandfather took out a map and a compass and drew a two-hour drive radius around Scituate, Massachusetts, where they lived. The compass line directed him to Deering, New Hampshire, where they found property for sale. Six acres of land in Deering were purchased, and an A-frame kit was ordered. It was 1963.

The completed A-frame—built by hand, with no electric tools—was completely off the grid and it would stay that way until 2012. Baths were taken in the stream on the property and rain water was collected for washing dishes. The scrappy A-frame even survived a small tornado in 1968, when it was moved six feet off its footing. When it was pushed back into place, the sliding glass door still worked—and still works today. In 1980, Sarah’s father built his house on the adjacent land (where he still lives today) so he would be able to help with the upkeep of the home. The A-frame is steeped in sentiment from the close family ties. Sarah, who spent weekends at her dad’s place, recalls evenings at the A-frame spent playing dominoes with her grandparents by kerosene lamp.

When Sarah’s grandfather passed away in 1991, her grandmother spent less and less time at their vacation home, and eventually the family decided the A-frame should be sold. When the discussion led to selling it to a friend of the family, Sarah burst into tears at the thought of losing the place which over many years had come to represent home to her.

Her husband, Matthew, sweetly assured her that the two of them would buy it themselves, despite having no idea how to fund the purchase. An agreement was drawn up for Sarah to buy her aunts’ shares based on a ten-year payback agreement, and her dad simply donated his share of the home’s worth. Soon Sarah and Matthew were able to make the A-frame their own.

The space is neither fussy nor fancy. Kids and dogs are welcome to make themselves at home. As a designer, Sarah is enthralled by the “A” shape. Any uniquely shaped living space is fascinating to her, and figuring out how to live without vertical walls has been a delight. Hanging art on non-vertical surfaces has been a fun challenge for the pair, as well as playing with a 1960s motif to pay homage to the origin year of the house.

Sarah has committed to using lots of textures and handcrafts in the details: the blankets are all vintage and hand sewn. Women and women’s work (such as quilting, embroidery, cross-stitch, and macramé) influence the decor, along with a few Scandinavian elements, as Sarah’s grandmother is Swedish and very proud of her heritage.

As an only child, Sarah has inherited her family’s history and heirlooms. Sarah’s grandfather’s tools can now be found throughout the A-frame used as decoration. There are not a lot of newly bought items in the A-frame, but the mix of new and old things makes the place come alive—a wonderful mix of family history, and Sarah and Matthew creating their own history in the home as the years go by.

Sarah and Matthew spend the majority of their time lounging in the living room. “Coffee in the morning, cocktails in the evening, and reading on the couch in between” is how they put it. Walking a mile down the road to swim in the pond, or sitting on the porch sipping a cocktail is about as outdoorsy as Sarah and Matthew get. But the connection to nature is still relished: they’re four miles out of town on a sparsely populated dirt road. Listening to the wildlife, hearing the leaves rustling in the wind, and seeing the stars come out at night are priceless ways to experience the calm of this cherished home, full of so many memories.

Sarah’s and Matthew’s hope as a couple is to grow old together in their A-frame and one day hand the keys off to their son and his children. As a designer, and as a granddaughter, Sarah has learned how to gracefully honor her family history while injecting the present and themselves into the home as well. It’s a home that represents where she came from and where she wants to be.

With no insulation to compete against the winter cold, and often visited by mice, the A-frame is inhabited only as a warm-weather vacation home. “It’s truly a cabin,” according to Sarah: “Wood and shingles, I say.”

The kitchen interior was built by Sarah’s father—she sketched out rough ideas for reconfiguring the space and he constructed it as a surprise. The raw cherry countertops were made from material Sarah’s father had on-hand.

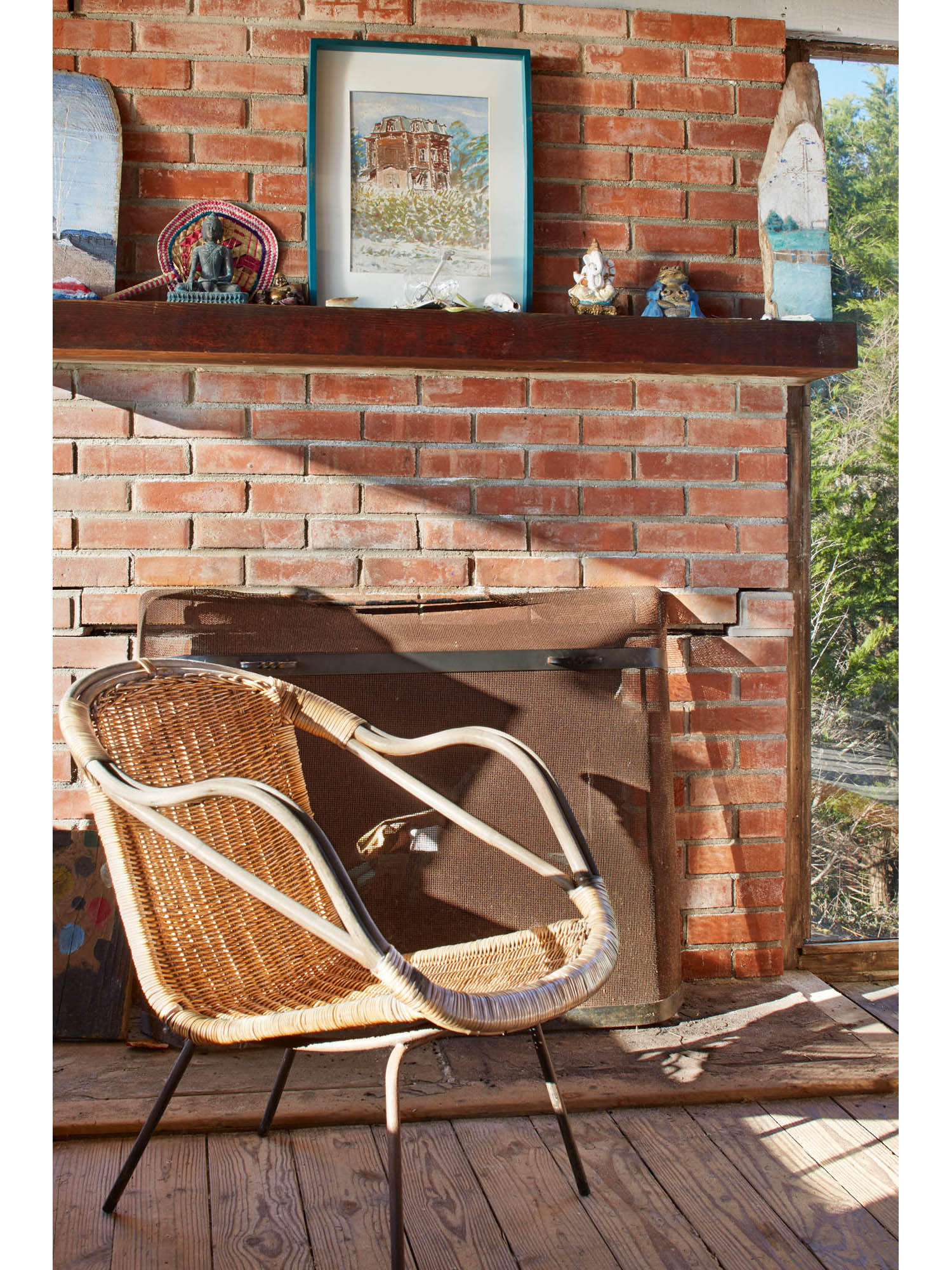

The fireplace, despite at a glance appearing original to the home, is actually a gas-burning fireplace and is a very recent addition to the A-frame. The chair is vintage.

Family treasures adorn shelves in the dining room: The wooden planer belonged to Sarah’s grandfather; the photos are a random collection of group shots Sarah began collecting years ago. The Time Life series belonged to Sarah’s grandparents and has been on that shelf her entire life. The bottom shelf is packed with comic books—a favorite genre for Sarah and Matthew.

Above and below: The dining room was built by Sarah’s grandfather in 1980 as an addition to the kitchen.

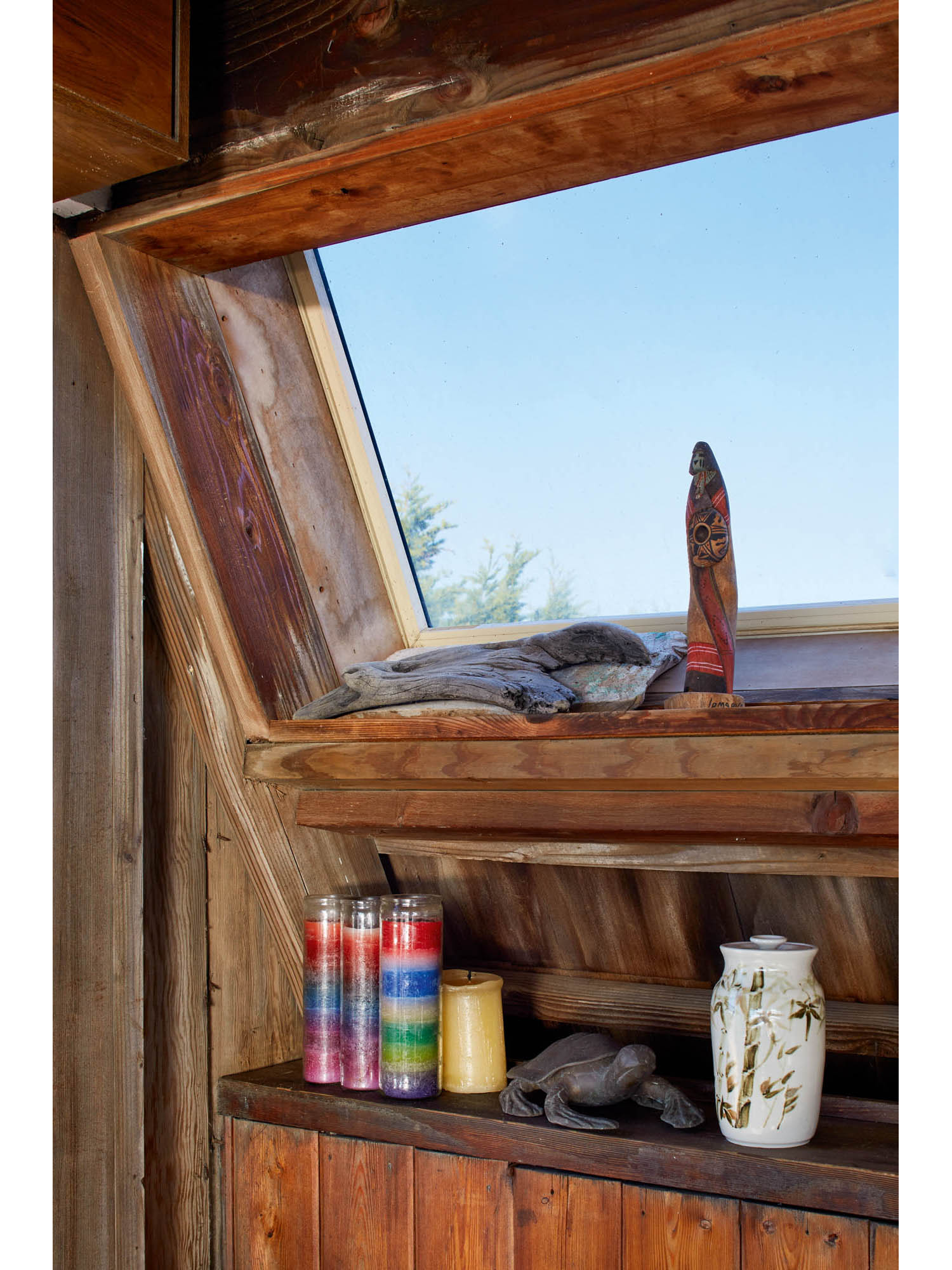

Vignettes of old (and sometimes new) things throughout the home convey fresh energy to the space.

The master bedroom was part of the 1980 addition completed by Sarah’s grandfather. The blankets in the home are all vintage and hand-made. The wicker elephant was a thrift store find.

The loft in the peak of the A-frame overlooking the living room is a special spot, used as a library, and often a quiet writing room.

The living room sofa belonged to Sarah’s maternal grandparents. Initially upholstered in a deep orange wool (and decades old), a recent canvas reupholstering gave the sofa new life.

The oar alongside the sliding glass door was hand-carved by Sarah’s teenage son while on a months-long outdoor expedition.

Above and below: Plenty of outdoor space has enabled Sarah and Matthew to host parties with as many as 40 guests in attendance, camping out overnight.

Summer Playhouse

Amagansett, New York

“Summer use playhouses” was how architect Andrew Geller described the beachfront homes he designed along Long Island, New York, throughout the 1950s and ’60s. Trained in industrial design, Geller designed these playhouses in his free time. Fashioned with modernist leanings, the homes were quirky, functional, and—with most being priced at under $10,000—quite affordable.

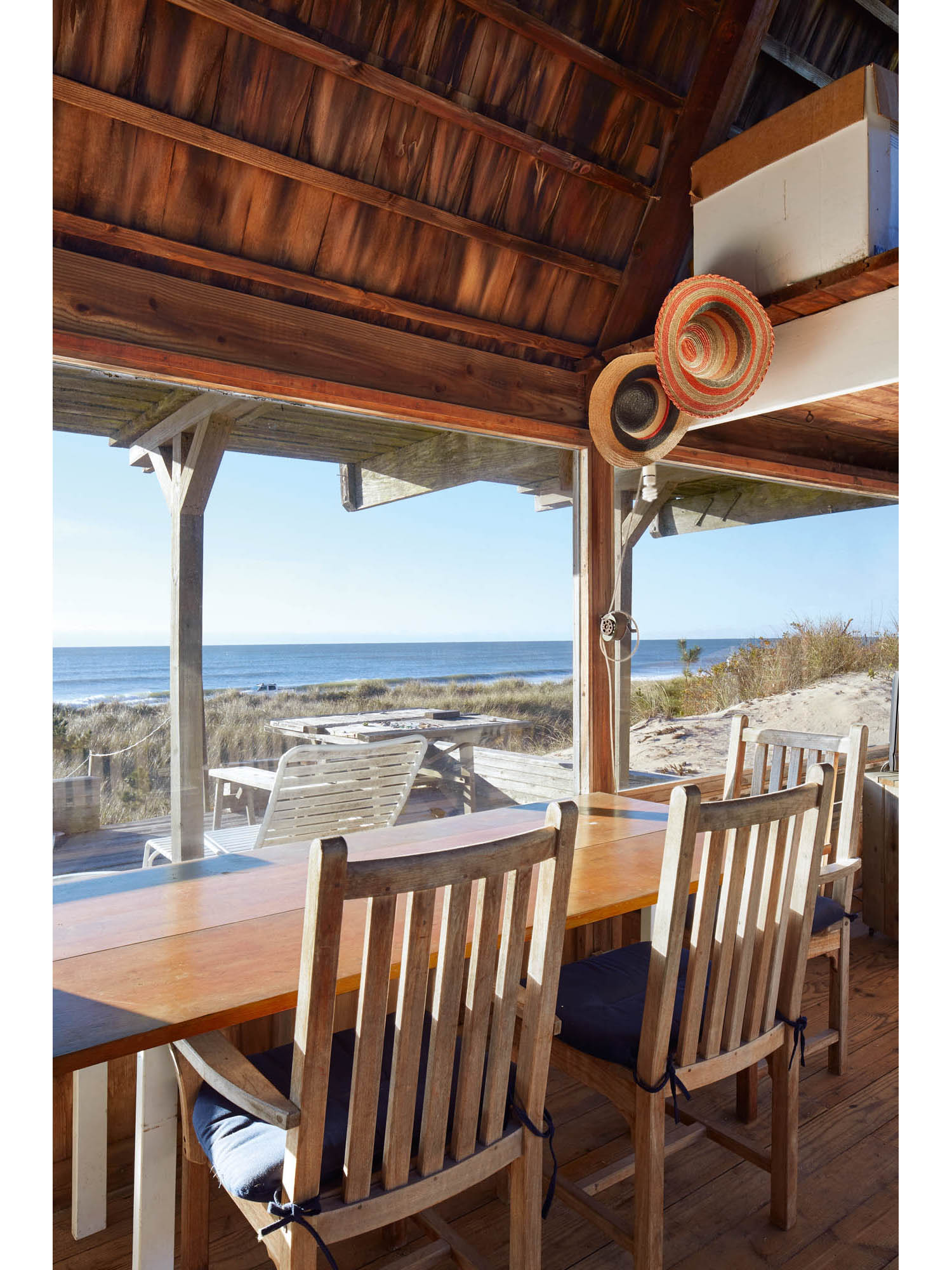

In 1958, Geller was commissioned by Leonard and Helen Frisbie to design a simple beach house on a dune in Amagansett, New York. Their only requirements were that it had to be simple and must include a small deck that would reach over the ridge of the dune. Six decades later, the home maintains its quirky beach house charm. A tad windswept after all these years, it now serves as an annual summer retreat for the Frisbies’ children, Lenora and William, and their families.

The two siblings agreed early on that elaborate renovations were neither needed nor desired. The beach house provides comfortable, though certainly rustic, accommodations for its visitors in the summer months: there is no insulation or heat, and a single indoor/outdoor shower serves as the most modern amenity the home has to offer. Pulley-drawn ladders lead up to the loft space for elevated views. Folding counters in the kitchen and tiny upstairs rooms with bunk beds make the most of the small space.

Proving to be a bit of a time capsule, most of the playhouse’s decor and effects are the Frisbies’ original furnishings. The few replacements made over the years were selected to look like they’ve been there since the beginning. Found beach objects displayed in nooks and on shelves become art. Expansive windows provide enchanting views of the sand and the sea.

Nature plays a very large role in the experience of its inhabitants. Immediate ocean access is one thing, but William’s son, Matt, testifies to the camp-like experience: “You find your body getting into the rhythm of nature, where you’re getting up with the sun.”

Month-long visits to the Frisbie house are filled with each occupant’s favored hobbies. Swimming, body boarding, reading, playing the guitar, and fishing abound. Many nights are spent camping out on the deck or on the beach below. Their days usually end with a surf or walk along the beach.

The Frisbie house carries on the tradition of simplicity and synchronicity with nature—and as Lenora and William plan to keep the A-frame in the family—the tradition will continue for years to come.

A guest house was added to the beach property in 1971.

A pulley-drawn ladder connects to the loft.

Above and below: The A-frame has become an eclectic time capsule as second and third generation family members spend summers there.

Leonard Frisbee painted this likeness of the A-frame; he used to paint on found beach wood while staying at the house.

The A-frame has maintained much of its original furniture and decor. Any additions have been chosen with the intention of matching the A-frame’s beachy rustic aesthetic.

The living room provides a front-row seat to the windswept beach. On less active days, sunsets are enjoyed from the oceanside deck with a cocktail in hand. On rainy days the family huddles inside for board games.

Plywood boards up a broken window on the second level of this beloved family A-frame. Skylights provide warmth and light to the interior.

Eagle Rock

Los Angeles, California

Bold orange doors and a smattering of potted succulents greet visitors at the former home of geologist Joe Birman, father and creative scientist who generally aspired to experience the unusual.

Joe grew up in New England but fell in love with Los Angeles after serving as an officer in the Army Air Corps in the 1940s, followed by moving to Southern California for his education. He went to the California Institute of Technology and UCLA, where he received his PhD.

His interest in the unusual was reflected in where he chose to live. Early on, Joe raised his family in a Schindler home, a place best known for its stylish modernity, until it was taken by the 134 Freeway construction. He would eventually purchase Eagle Rock House because he could not resist the unique architecture. The 1963 A-frame (and its eponymous neighborhood) takes its name from a prominent rocky outcropping in the area resembling an eagle with outstretched wings.

Joe bought the Eagle Rock A-frame from a well-known Los Angeles DJ. He found the idea that an artist had owned the home before him most intriguing. The home was designed for people to enjoy. Neighbors were treated to concert-level piano music of Beethoven, Mozart, or Chopin—if not by Joe’s hands on a 1909 baby grand piano, then certainly from his amazing midcentury stereo system. The vaulted ceilings are a delight for their acoustics, but even more so for the view they afford of the San Gabriel Mountains. Joe never tired of that view for the roughly forty years he lived in his A-frame. Nor did anyone who would come to visit. The Eagle Rock A-frame is truly a special place by any measure: though humble in size, it has a grand impact.

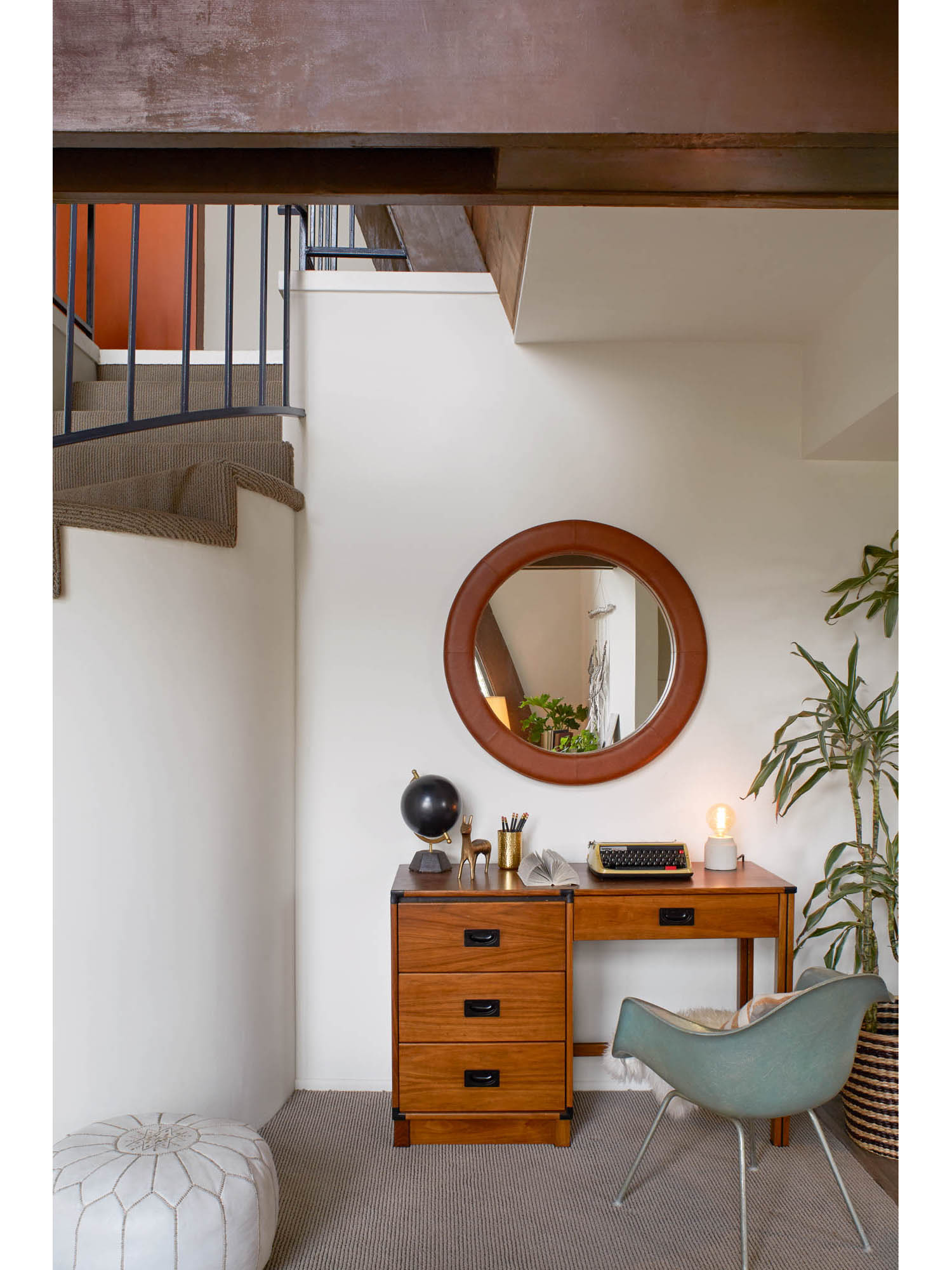

Upon entry, guests are greeted by a showstopping window spanning two levels of the home.

A quiet nook beside the stairs to do one’s work.

Joe had an eclectic taste in furniture; while the home was staged and photographed after his passing, the A-frame was always filled with unique pieces, 1960s and earlier.

The living room opens onto a partially sheltered deck, ideal for entertaining and offering enviable views of the San Gabriel Mountains.

In the 1980s, Joe worked with an architect to design a third bedroom/office space to match the style of the house. The fireplace was added at that time.

Two of the three bedrooms decorated in a mid-mod bohemian style.