It was always the walk that did it.

The walk from the village to the stadium bus was when I mentally flicked the switch. I was now in my zone, and there would be no distractions. I’d managed to keep relatively chilled out during the day, and it was only when I’d had a shower and started to get my numbers and gear ready that the nerves hit.

I was in the second semifinal at 7.23 pm, with the 100m hurdles final at 9 pm.

The good news was my back was nowhere near as bad as the previous day and I was able to warm up properly. I found that music helped take me to a relaxed place while I bounced around the track. It was an escape from the seriousness of what I was about to do. As soon as I took the headphones off I was always taken a bit by surprise. ‘How quiet is it?’ I asked.

Everything had gone well until we got to the call room. Dawn Harper was in the semifinal ahead of me, so I was anxious to see what time she ran. I wanted to be the fastest qualifier for the final because I felt it reminded the others that I was still the one to beat.

As soon as Harper’s results flashed up, I was momentarily stunned. And then angry. She’d won in a personal best time of 12.46.

‘Jesus,’ I said.

How could she run that fast? She’d never done that before in a semifinal. I had to respond and clearly work a lot harder than I’d planned. As we gathered at the blocks I was more fired up than I’d been in a while. I had to beat her time. I had to.

It was almost the perfect start and I was clearly a long way ahead by the first hurdle. There was no relenting, although again I clipped the eighth hurdle, which was exactly what I’d done in the heat. It was only a momentary glitch and I knew the race was fast as I cleared the last and started my dip for the line.

‘Yeeessssssss,’ I yelled as I crossed the line and pumped my fist when I saw 12.39 on the clock.

I’d done it, and almost straightaway I started to do my calculations comparing the time with the world championships – it was .03 of a second slower than Daegu. For some reason, right then I knew I wouldn’t be breaking the world record in the final. But what made me not dwell on that thought was the next thing that entered my head: I was going to win the Olympic gold medal. I just had to make sure I kept it together over the next 90 minutes.

When I met Sharon I was having a bit of trouble with my breathing because I was still so hyped from the semifinal run. Finalists were offered a buggy to take them back to the warm-up track, but we decided to walk because I needed to calm down and slow my breathing down. It worked, and when we got there Sharon suggested we just stroll a couple of laps.

‘I have to win this race. I can’t lose this Olympic final,’ I said.

‘You won’t. You won’t,’ Sharon kept saying.

I didn’t stop. I don’t know if I was telling her or I was telling myself.

‘I can’t lose this Olympic final. I can’t let them win it. I have to win it.’

My coach was emphatic. ‘You will.’

After some light exercises it was time. Sharon walked me to the call room and we talked about the eighth hurdle.

‘You have the feel of the track now, so going into hurdle eight you just have to chop your stride,’ she said.

‘Yep, I can do that.’

Then we stopped and embraced.

‘It’s your night to shine, Sal,’ Sharon said. ‘All of the flashes are going to be for you. Go out and do it.’

* * *

The wait was annoying.

For the heat and semifinal we’d been rushed through the call room, but it was the opposite for the final. My nerves were increasing by the minute. I didn’t like sitting for long periods because if I did, I knew my back would stiffen.

When we finally got out onto the track I was feeling good and focused. But again there was a delay. This time there was a medal ceremony that held us up, and as we were waiting it started to rain, which made me chuckle.

Of course it was going to rain on my night; we were in England, which has the worst weather, so it shouldn’t be a great surprise.

I just wanted the race to start – but now they had to do the introductions, which always took forever. Each runner was introduced with their name, country and achievements. I was in lane seven, so it seemed like ages before the cameraman was in my face. I knew I’d get a good reception because it had come out in the lead-up to the Games that because my mother was a local there was a possibility that I could get an English passport.

The British journalists had jumped on it and kept asking me if I would consider swapping allegiances. That was never going to happen, but the crowd had clearly embraced me as I got a massive cheer, which was a nice shot of confidence.

Once the starter called us up, I started working my way through my starting cues.

Fast start. Strong start.

My heart was racing, but then I realised they also had mega-loud heartbeats echoing through the loudspeakers in the stadium.

You’ve got to be kidding me.

They left them beating right up until the starter called ‘Set’ and then switched them off.

Fast start. Strong start.

It felt normal. It wasn’t anything out of the ordinary, but I was safely out and over the first hurdle.

Keep it together.

My rhythm was good as I approached halfway.

What happened in the next six seconds changed my life forever.

When you stop and think about what a small space of time that is, that determines extreme euphoria or heartbreak, it’s scary. Sit down and literally count to six. It blows my mind every time.

I wasn’t counting midway through the Olympic final, but my mind was racing as I pleaded with myself to stay upright. Then I pleaded with the athletic gods to ensure I had crossed the line first and not Dawn Harper.

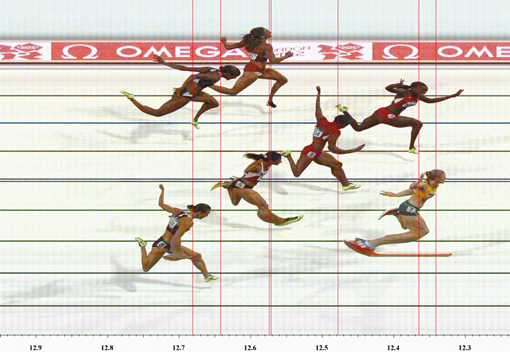

Crossing the line to win gold in the women’s 100m hurdles final at the London 2012 Olympic Games at Olympic Stadium on 7 August 2012 in England. (Photo by Ezra Shaw/Getty Images)

Now everything was slow. It had gone from one extreme to the other. Frantic thoughts and movement in the race to standing still, staring at a screen with the future direction of my life depending on what appeared on it.

I’m not a religious person, but praying was the only thing I could do. I thought I’d won; I just needed confirmation. Then it appeared. My name. First.

I screamed and fell to the track. I was on my hands and knees, gripped by shock.

I’d beaten Harper by .02 of a second. American Kellie Wells came up and grabbed me in a massive bear hug because she’d won the bronze medal in a personal best 12.48. Lolo Jones had again missed out, finishing fourth in 12.58.

The Omega photo finish image of the winning moment of the women’s 100m hurdles final at the London 2012 Olympic Games. (Photo by Omega via Getty Images)

‘Where’s Sharon?’ I started screaming.

I saw the Australian team was just past the finish line and I located Eric Hollingsworth, who was on a chair jumping around.

‘Where’s Sharon?’

He was looking at me and pointing to his right, but I was confused as I was only looking at him and not his hand. My brain was frazzled – I’d just won an Olympic gold medal.

Then I spotted her and she made her way down to the front where we hugged like never before.

‘Thank you so much,’ I kept saying. ‘Thank you.’

I could tell she was excited, but the overwhelming feeling for both of us was relief. It had been a two-year build-up, and the pressure had been intense – but we’d done it.

Hugging my coach, Sharon Hannan, after winning the gold medal in the women’s 100m hurdles final at the London 2012 Olympic Games on 7 August 2012 in England. (Photo by Alexander Hassenstein/Getty Images)

In reality that dream had started 12 years before, when I saw Cathy Freeman win in Sydney. Now, I was also an Olympic champion! And I’d set a new Olympic record in the process.

The victory lap, with Aussie flag draped around me, went way too fast. You’re on such a high that you can’t help but go faster than normal, and I felt like I could even run a 50-second 400m.

At the 300m mark I saw my aunt with her friends, which set off more screaming. I had no idea where anyone else was and I was too busy soaking up the well wishes from the crowd, which was giving me a standing ovation.

Then I spotted Mum, Kieran and Robert just up from the 100m start. Seeing the looks on their faces pulled at the heartstrings. It was a magical moment.

I learnt later that they’d almost had a disaster with the tickets. Their original tickets had been really bad seats, so Robert had arranged with adidas to swap for some better ones. But then on the train ride to the stadium at 5pm, Kieran had noticed the tickets they’d been given were for the morning session. A few frantic phone calls later and everything was thankfully sorted.

I felt like I was floating as I made my way to the mixed zone.

‘I don’t feel anything right now,’ I told one of the television interviewers. ‘I’ve just wanted it for so long.’

It took me 40 minutes to slowly snake my way through the press before the three medallists were taken into a press conference. That was a lot of fun because I got on really well with Kellie and Dawn, who was like a comedian a lot of the time.

The medal ceremony wasn’t until the next night, which was very frustrating.

I had more TV commitments and received a nice surprise when I bumped into my good friend Australian cyclist Anna Meares on my way back to the village. I hadn’t even known she’d been competing that night, let alone that she’d also won a gold medal, until I was in the mixed zone after my race and people were asking me what I thought about Anna.

Everyone had decided to shield the result from me because they didn’t want to put extra pressure on me. There was more screaming and hugging with Anna before I finally made it back to my apartment at 3.30 am.

There was no-one there and all the lights were off, so I sat on my bed and got my computer out. I’d switched off Facebook for the last few days because I didn’t want it to be a distraction. It was nice to go through all the messages, but my peace only lasted ten minutes before Alana and Dani walked in and the celebrations began again.

After a couple of hours’ sleep, I was up and back in the media circus, starting with a joint press conference with Anna, which was lots of fun.

I finally got to spend some quality time with Mum, Kieran and Robert at a Qantas cocktail party before heading back out to the stadium to get my hands on that gold medal. It was a joke that Kieran and Mum had to again pay for tickets – we’re talking several hundred pounds – just to be out there to see such an important moment in my life.

The medallists were told to be there an hour beforehand, and when we arrived they said there would be a 20-minute delay. That soon turned into an hour. The three of us were soon sick of being stuck in the medal ceremony room, so we decided to go outside and watch some athletics.

When we got up to the athletes’ stand, the gates were shut because the area was full.

‘Are you serious?’ Kellie Wells said. Her boyfriend, Netherlands sprinter Churandy Martina, was about to run, and she was screaming at the attendant to let us in.

It worked, and we sat there for a while before heading back to the medal ceremony room, where again we were told there was a delay.

Luckily Kevan Gosper, the Australian representative from the International Olympic Committee who was presenting the medals, was there and he offered to take me up to the royal box. I felt like the queen sitting up there in the front row, and I texted Kieran, who looked up and saw me doing my best royal wave.

It turned out they’d delayed the medal ceremony because the women’s long jump was getting exciting, which pissed me off because the hurdles final the previous night had been delayed because of a medal ceremony.

By the time we got out to the medal dais, the stadium was half empty and it felt like a bit of an anti-climax. It was disappointing, and I wasn’t feeling the way I should have been until they started announcing Kellie’s bronze and for some reason I felt tears welling. I kept them away, and they were well and truly gone by the time the gold medal was being placed around my neck.

Touching the gold medal instantly made everything real.

The sound of the Australian national anthem being played throughout the Olympic stadium also brought goosebumps.

Dawn Harper of the United States kisses her silver medal, I hold up my gold medal and Kellie Wells of the United States holds her bronze medal on the podium at the London 2012 Olympic Games. (Photo by Quinn Rooney/Getty Images)

I had a permanent smile on my face for the next few days as I soaked up my new title of Olympic champion.

It was only when I went back to the track a couple of days later that it disappeared. I was planning to continue racing in Europe because I was desperate to claim the Diamond League title that had eluded me the previous year.

But halfway through my first drill, I knew that wasn’t going to happen. My back was hurting again and I couldn’t do anything.

‘I think I’m going to have to pull out of the rest of the season,’ I told Sharon.

Then I burst into tears.

‘Why am I crying? I’m the Olympic champion,’ I sobbed.

We decided to delay announcing my decision because I didn’t want to go home on the charter flight with the rest of the Australian team. I wanted to spend some more time in England with my family, as my aunt had a special gold party planned.

She went above and beyond. In just three days, she transformed her house into gold. There were gold posters and ribbon from floor to ceiling in every room. Each guest had to wear gold, and they were presented with a Cadbury’s chocolate gold medal when they walked in the door.

My grandfather had died just before I won the IAAF Athlete of the Year, and Mum’s sister, Wendy, kept his ashes above the oven in the kitchen.

To mark the occasion, she added some little gold flakes into the urn. ‘Look, Michael is here too,’ she said.

It was the party to end all parties, and a perfect way to celebrate what had been a perfect year.