It was the only race I watched.

Kneeling down on the floor, I got as close as I could to the TV screen to see her. Cathy Freeman looked amazing in her hooded jumpsuit and, like millions of others, I was screaming as she hit the front in the home straight to win the Olympic 400m gold medal. I was fascinated by her and what she’d just done.

‘How do I do that?’ I wondered. ‘How do you train to be the best athlete in the world?’

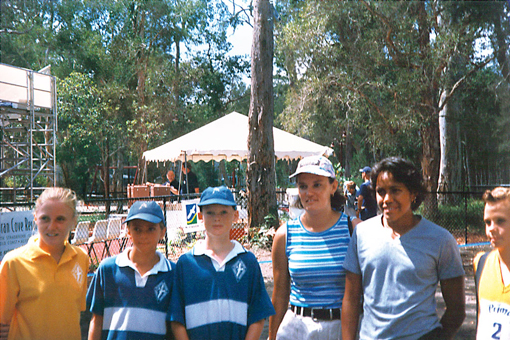

I’d been lucky enough to meet Cathy a couple of years earlier at the opening of the Couran Cove Resort on South Stradbroke Island. A couple of kids from each primary school in the Gold Coast area were selected to meet Cathy and also take part in a clinic with the Great Britain team, which was training at the nearby Runaway Bay complex.

At the opening of the Couran Cove Resort on South Stradbroke Island where I got to meet my hero Cathy Freeman.

They had us doing a 60m sprint and then some hurdling. I went flat out in the first race, and one of the athletes, whose name was Katherine Merry – she ended up winning the bronze medal behind Cathy in Sydney – approached me afterwards. She seemed surprised at how quick I was, which was pretty cool – although it was a reaction I was starting to get used to receiving from adults.

Our hurdles mentor was former Olympic 100m champion Linford Christie. He was this massive man with dreadlocks, and I was determined to do it exactly the way he showed us. All the other kids managed only one bound over the hurdle, but I kept going. Linford seemed impressed, and I was pumped. I never used to say much, but secretly I liked to use my actions to show off, so I was pretty proud of my efforts.

The day got even better when we finally met Cathy and I got her to sign my cap. She was very quiet and looked like she wanted to be by herself, but everyone was desperate to get a piece of her.

I was so excited to meet Cathy and was lucky enough to get her autograph on my cap – she was so inspirational and I really wanted to be like her.

Mum managed to snap a few photos of the two of us, which quickly took pride of place in our house. And now, after the Olympics, it was a picture of me with an Olympic champion!

I couldn’t stop thinking about how much her life must have just changed. Mine had certainly gotten a little tougher in 2000, as Sharon introduced hurdles into my life. I thought I was a sprinter, not a hurdler, even though I dabbled with hurdles in Little Athletics. But my response when my coach suggested it was the same as always: ‘Well, I’d better do it then.’ The bonus was that I got to train an extra night with the squad, which made me happy. Sharon trained the hurdlers on Monday night and sprinters on Tuesday and Thursday.

I was an expert on the bus routes around the Gold Coast because that was how I got around. We were living in Labrador, so to get to school it took about an hour, given I had to get a bus into Harbour Town, then change to another bus to get out to Helensvale State High School.

Getting to training after school was only one bus ride but, because it stopped so many times to pick up other schoolkids, it took ages. I started training at 5 pm and would wriggle into my running gear on the bus. Normally we’d train for two hours and I’d either get the bus home or get a lift with Sharon or her husband, Peter.

More often than not, my post-training debrief would centre around how much I disliked the hurdles because I hit so many in training and was quickly getting battered and bruised.

My first national high school championships were in Adelaide and I qualified in the 100m, 200m and 90m hurdles. I didn’t do very well in the 100m, finishing fifth or sixth, but I was excited to make it to the final of the hurdles, given it was my first season doing them.

The 200m final was first, though, and I was always nervous and sick before doing 200s. It felt like it was just that little bit too far, as I didn’t have the speed endurance required just yet. I found something, though, and ran a massive personal best, cracking the 25-second barrier for the first time, finishing third behind two other Queenslanders in 24.92 seconds.

This excitement flowed on to the hurdles final, but something went amiss at the first hurdle and I got on my wrong leg, which completely threw out my rhythm. I tried to pick up pace but overcompensated and ended up smashing into the sixth hurdle and then hitting the deck.

It was so embarrassing, but I had a sneaking suspicion it wasn’t the last time the barriers would get the better of me.

* * *

‘Why am I here?’

I was so angry at Sharon. We’d just walked into the call room – which was where athletes checked in with officials to confirm their participation before each race – and were only minutes away from walking out on the track for the heats of the Under 20 100m at the 2001 Australian championships in Brisbane.

The under 20! I was only 14.

‘What am I doing here?’ I kept asking her.

‘You are here because you deserve to be,’ Sharon said. Her reasoning was that to run my best I had to run against the best, and people who were faster than me.

A month earlier at the under-age national championships in Bendigo I’d won the Under 16 100m and 200m, medalled in the long jump and high jump, and anchored Queensland’s 4x100m relay team, which set a new Australian record. The times hadn’t been great, though, which is why Sharon was throwing me in the deep end. I didn’t like the idea.

‘I’m 14 years old,’ I kept saying. ‘I’m going to be terrible against these girls.’

Thankfully I was wrong, and my coach had gotten it right again. Sharon had wanted some competition, to have faster girls in front of me so I would be pushing to go with them.

The problem with that theory was that they were never in front of me. I not only won my heat but I also smashed the 12-second barrier for the first time, clocking 11.94. The final was even better, and I took out the Australian Under 20 title in 11.91. It was a major breakthrough and Sharon was convinced it was a game-changer.

Suddenly Athletics Australia was keen to talk and we were summoned to a meeting about the World Youth Championships. Both Sharon and I had never heard of such an event.

It turned out that my 11.91-second run had qualified me for the championships, but there was a hitch. AA was saying that because I hadn’t set the time in the right age group – I did it in Under 20 and not Under 18 – they weren’t going to select me.

‘Are you serious?’ I said.

We were both bemused. I got the impression they thought my victory was a fluke and that at 14 I wouldn’t be able to handle the pressure of racing against older girls on the world stage.

In the end I was like: ‘Whatever.’

We weren’t too worried about it, and looked at it as just another step on the learning curve that Sharon and I were on together. She’d gotten into the sport almost by accident, and was figuring out on the run what was required to coach at the elite level.

It had all started when her nine-year-old daughter, Richelle, came home from school with a flyer for Little Athletics. They were living in a small town called Gordonvale, south of Cairns, and Sharon was working for a local airline. She started helping out on Sunday mornings at Little A’s; her first task was managing the tape measure for the field events.

The next season the people in charge changed it to a Wednesday afternoon, which didn’t suit Sharon and another family – the father of that family was a navy captain – so together they decided to start their own club, and Cairns Little Athletics was born.

Funnily enough, after going through all the red tape to set it up, the navy captain was redeployed, so Sharon was left running the whole show. In her first season she had 83 kids sign up.

Realising she’d better get her head around track and field, Sharon went off and did a coaching course. Even when her daughter progressed to junior level, where she became a race walker and got as far as the state championships, she stayed involved as the zone coordinator for Little A’s.

And that’s how she met her husband, Peter, in 1989. He was an athletics coach from the Gold Coast and was part of a group who’d travelled up there to conduct coaching clinics. They hit it off and started writing to each other. One thing led to another and, when Richelle had finished Year 12 at the end of 1991, they relocated to be with Peter. Sharon and Peter were married on New Year’s Eve 1992.

When the Gold Coast City Athletics Track opened in 1998, Sharon, who had been on the track advisory committee, volunteered to be the caretaker for the first few months of its operation. Soon the council realised it was a full-time job and she was appointed caretaker manager until they called for tenders for the management contract. Sharon, and Peter, who had been a part of the Gold Coast Athletics Club for more than 20 years, won the contract, and their company, Sports Credentials, has run the facility ever since.

While Sharon was always reading coaching manuals and asking questions to broaden her knowledge, what she had quickly developed was a penchant for setting big goals. And often she wouldn’t even tell me about them before blurting them out at a crucial moment.

One such occasion was during our first meeting with the Australian Olympic Team head coach, Keith Connor. He was a scary man, big in stature, and had an intimidating manner about him.

He had started by asking me about what my goals were in the sport.

‘I don’t know, I just want to make the Olympics,’ I said.

He gave me a look, one almost of disgust.

‘What happens when you make the Olympics?’ he asked. ‘What’s going to happen then? Are you just going to stop? You need to have some more specific goals than that.’

I was almost shaking. ‘I don’t know … I just want to go to the Olympics.’

‘That’s not enough,’ he bellowed. ‘Do you want to make the final or get top eight or get a medal?’

‘I don’t know,’ I repeated again. ‘I guess I want to win a medal one day.’

Then he paused and it was like something clicked. ‘How old are you?’

‘I’m only 14.’

Connor looked shocked. ‘Oh my God, I’m so sorry. You’re a baby.’ He was very apologetic, but then Sharon piped up.

‘She is going to run 11.6 seconds in the 100m and she’s going to make the 2002 Commonwealth Games team in the relay.’

I looked at her with dismay. This was the first I’d heard of such a plan.

‘Sharon,’ I said, and gave her a dirty look.

She had another crazy plan, which she didn’t mention in that meeting, and that was to turn me into a heptathlete. She and Peter had discussed it at length, and they’d introduced me to our best heptathlete of all time: Jane Flemming, the 1990 Commonwealth champion.

They figured I was already a long way down the right track, given my success as a junior in the high jump and long jump. The heptathlon had seven disciplines – 100m hurdles, high jump, shot-put, 200m, long jump, javelin throw and 800m – and it sounded like a whole lot of hard work.

Once again I didn’t dismiss it because I was happy to go along with whatever they thought, but for the moment those plans were on hold as I had a sore foot. We’d had it looked at, but the initial diagnosis for my first injury scare was that it was no big deal.

Something told me that was wrong.