The Foreign Cinema vision is as aspiring today as it was in 1999, when local newspaper headlines read ambitious mission restaurant to mix films with food. San Francisco, backdrop to and seductive character in numerous iconic films—Vertigo, Bullitt, The Conversation, Chan Is Missing, Dirty Harry, Interview with the Vampire—celebrates both restaurants and cinematic efforts and embraces emerging food concepts and cinema as high art forms. This time, the two concepts would fuse.

Mission Street in the 1950s included the sprawling, rollicking Miracle Mile, where working-class masses shopped competitively before flocking to the cinema, filling as many as ten thousand theater seats. Community gathered, cultures celebrated, and lives were lived on the vibrant boulevard. By the ’90s, five landmark theaters dotting the old Miracle Mile corridor sat dormant, in arrested decay, and symbolized the rapidly shifting tide of big theater fragility in places where neighborhood rituals of shopping and communing disappeared with the always-changing city. The restaurant’s founding team—visionary Jon Varnedoe and his wife and muse, Juliet, Michael Hecht, and passionate financier Bruce McDonald—believed in and understood the churning, encompassing dream coming together day to day: reinvigorate the art of cinema in the Mission, adding good food to relish under the stars.

In 1997, our address at 2534 Mission Street housed a 99-cent store, two shuttered businesses, and a rare, sizable open courtyard ankle deep in debris. Since 1926, past lives of the unique site include a See’s Candies Store, Knit Kraft sportswear retailer, optometry and medical offices, and Byron’s Shoe Emporium. Jon wrestled for the lease to unify the whole space and envisioned revitalization of the neighborhood’s past cinematic glory, capitalizing on the cinder block wall riddled with bullet holes in the courtyard—the size of the famous Castro Theater—while serving French bistro food.

Construction began on this new gathering place for artists, filmmakers, and San Franciscans in search of the new in 1998. Simultaneously, the shuttered Cine Latino theater—once the Rialto, then the Crown—across the street began dismantling its wood floors, tossing the boards into a dumpster. Jon inquired about them and was given the planks on the spot, with the condition that he take them immediately. The crew moved between the sites, preserving the flooring and, months later, installing the genuine pinewood theater floor as the foundation for Foreign Cinema’s main dining room. The gently arced metal railing crowning the mezzanine dining room, also salvaged from the Cine Latino across the street, gave the mezzanine floor a grand theatrical feeling.

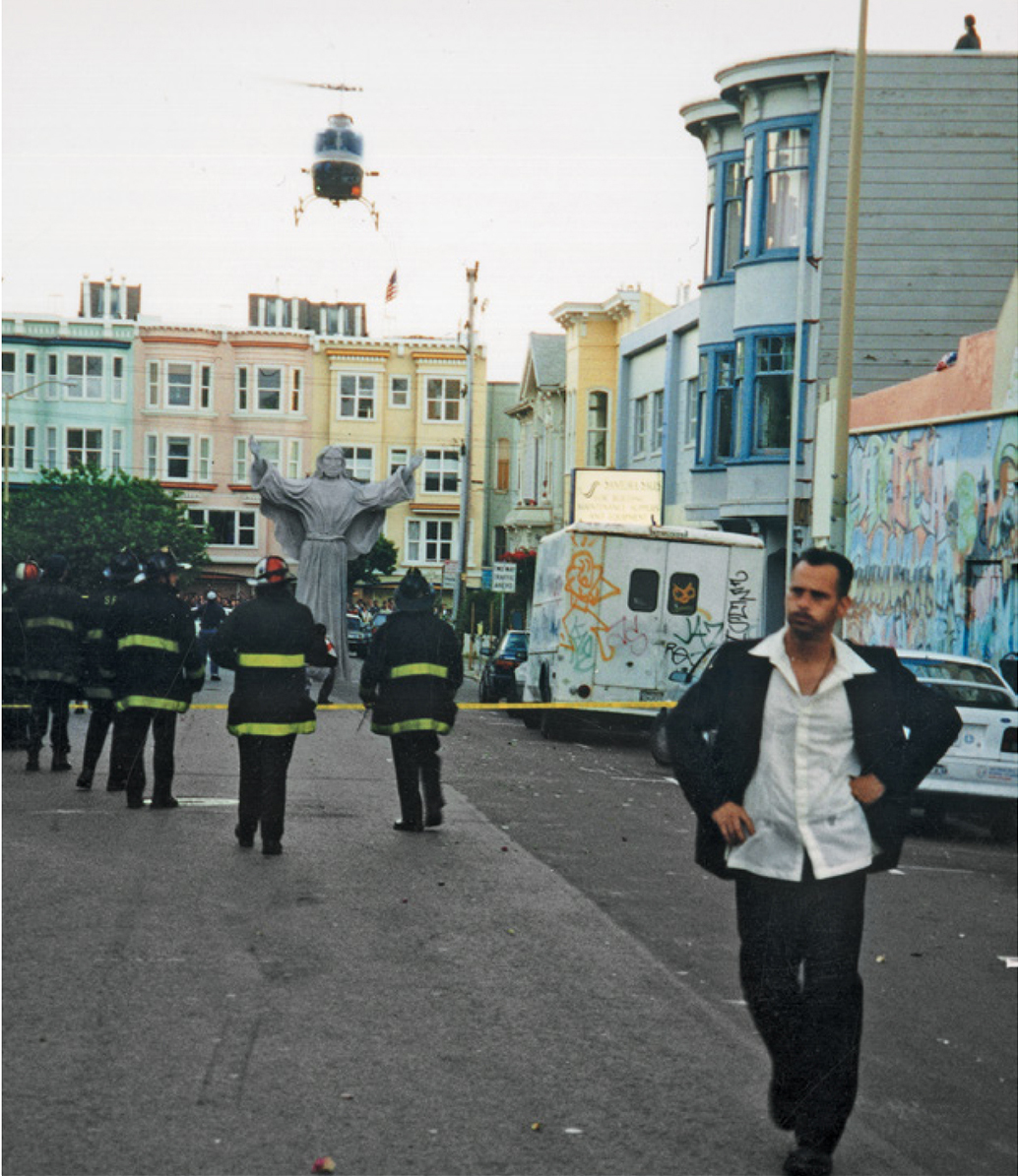

As construction neared completion, a big opening night was planned, with a local artist commissioned to build a Jesus statue to annoint the courtyard via helicopter, replicating the opening scene in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita. Awaiting the opening party in August 1999, the adoring public signed ominous legal waivers, should the chopper and statue meet an unfortunate fate on their dramatic courtyard entry. Four different cameras with tracks were mounted on the roofs to record the arrival. Though Jesus failed to show—the rookie pilot in charge declaring the statue too heavy for the helicopter—the party raged forward into the night. Troupes of pagan fire dancers christened a new, enchanted setting San Francisco had yet to experience.

The dueling food and film concepts were synthesized into a nightly experience, and the films were not always foreign. Chinatown, Annie Hall, Jaws, and other classics flickered on 35-millimeter film from spools and trays, using the projector given to Foreign Cinema by the neighboring iconic New Mission Theater. The double feature played nightly to a city hungry for food, film, and a unique experience.

The theater-style venue and authentic drive-in speakers, combined with French bistro food, offered a blueprint for the extraordinary. But the daily reality could be rough, as the luster dimmed with the unknowns of the dot-com bust gripping San Francisco. The additional financial drama of the management team’s landmark sister restaurant, Bruno’s, meant that their operational playbook went from offense to defense to a Hail Mary pass in the troubled, turbulent neighborhood.

In July 2001, we entered a restaurant nearing bankruptcy, calling Foreign Cinema our enfant terrible in need of tough parental love.

Construction to build Foreign Cinema began in 1998.

On opening night in 1999, a helicopter was hired to deliver a Jesus statue to Foreign Cinema’s courtyard during the opening party. The statue did not arrive as planned, but the party continued nonetheless.

In the beginning, the charming restaurant, riddled with romance and conflict, was hard to locate. No address was listed in the phone book. The front entrance proudly featured no signage. Upon arrival, guests didn’t know what to expect, asking when the movie started. Serious film buffs scorned the idea of food interrupting a movie, calling the idea “gimmicky.” We understood immediately that the concepts of film and food required better integration.

Our charge: fortify Foreign Cinema with a daily changing menu, vibrant and enduring, summoning the spirit of a Roman market square. Bring experiential quality to guests on all levels, weaving incongruous parts into one harmonious whole. Work with local producers, growers, and fishmongers to express our native hearts and souls. Reflect our coastal regions with a variety of oysters on the half shell and seafood menu. Build up a steady clientele of regulars who feel both at home with us and well nourished. From the start, the setting dictated our cuisine, but the menu always came first: alluring, with something for everyone and the clarity of flavors punched up to match the grandeur of the space. The food had to be vigorous in taste, to fill a grand piazza projecting cinematic classics, as well as the adjacent dining room centered near the roaring hearth. Yet the menu could not be fussy, pretentious, or overworked. From perfectly grilled steak frites to pristinely shucked oysters, we created a palate with sex appeal, based on what we truly wanted to eat.

Ultimately, we would turn a film plus food concept into a food concept that featured film. With original financier and partner Bruce McDonald, we forged a new lean team to work intensely to pay off all debt and address the fledgling business with our hearts and minds, and a generous sense of spirit.