1 Few players are as identified with a particular number as Gordie Howe is with No. 9. But it’s not the only number he wore while playing for the Red Wings.

Howe was wearing No. 17 when he made his NHL debut and scored a goal against the Toronto Maple Leafs on October 16, 1946, and he wore it throughout the 1946–47 season, when he scored seven goals and finished with 22 points in 58 games.

Howe didn’t don No. 9 until his second season with Detroit. He reportedly was perfectly happy with the number he had and didn’t want the change until he was told that the lower number would give him a lower berth in the Pullman car the Red Wings used on road trips during the era in which teams did most of their travel by train.

Of course, Howe went on to wear No. 9 until he finally hung up his skates in 1980.

“It’s a pretty classic number, and a lot of great players have worn it, but what it meant to me was that I got a better night’s sleep,” Howe told the National Post in 2014. “Many people may not know that my first number with the Red Wings was No. 17 until early into my first season. The No. 9 became available, and it was offered to me. We traveled by train back then, and guys with higher numbers got the top bunk on the sleeper car. No. 9 meant I got a lower berth on the train, which was much nicer than crawling into the top bunk.”

2 It seems incredible that Gordie Howe’s NHL career included just one 100-point season. Then again, he wasn’t playing today’s 82-game seasons. When Howe came to the NHL in 1946, the season was 60 games long, and from 1949–50 through 1966–67, teams played 70 games. Howe led the NHL in scoring six times during that span, finishing with anywhere from 81 to 95 points. Projected over an 82-game season, that range would be 95 to 112 points.

But in terms of actually producing 100 points, it didn’t happen until 1968–69, when Howe finished with 103 (44 goals, 59 assists). Perhaps most amazing is that he did it by getting four points (two goals, two assists) in the Red Wings’ final game of the season against the Chicago Black Hawks (as they were known then) on March 30, 1969, just one day after his 41st birthday.

Howe’s 100th point came when he scored 33 seconds into the second period, beating Chicago goaltender Denis DeJordy.

But he wasn’t done there. Howe scored his 44th goal of the season by beating DeJordy at 11:02 during a Detroit power play.

His 102nd and 103rd points came when he assisted on third-period goals by Frank Mahovlich and Garry Unger, capping a late-season surge in which Howe piled up 15 points (six goals, nine assists) in Detroit’s final nine games.

The only downside to Howe’s record is that his historic night came in a 9–5 loss at Chicago Stadium, one that capped a season in which Detroit finished 33–31–12 and failed to qualify for the Stanley Cup Playoffs.

That 103-point season was the biggest of Mr. Hockey’s pro career and his only 100-point performance in the NHL. However, he did reach the 100-point mark twice while playing for the Houston Aeros of the World Hockey Association. In 1973–74, his first season in the WHA after returning to the ice following a two-year retirement, Howe finished with an even 100 points (31 goals, 69 assists) in 70 games. Two years later, Howe put up 102 points (32 goals, 70 assists) in 78 games, superb numbers for a player of any age, but almost incomprehensible for someone who had turned 47 just before the end of the regular season.

3 The NHL instituted the shootout in 2005 in order to eliminate ties. The league eliminated overtime in 1942 to accommodate travel schedules during World War II; in 1983, it brought back a five-minute, sudden-death OT in which the winner got two points in the standings and the loser none (each team got a point in the standings if no one scored and the game ended in a tie). In 1999–2000, the NHL changed the rules to give the losing team one point in the standings, while also reducing the number of skaters for each team from five to four.

The Red Wings weren’t particularly successful in shootouts from 2005 to 2016. They were 49–65, and at one point in calendar year 2013, lost 11 consecutive shootouts.

Detroit won its first shootout of the 2015–16 season, lost the next five, and won the last one, 2–1, against the Columbus Blue Jackets on February 23, 2016. Maybe that was an omen of better things to come, because in 2016–17, the Red Wings were unbeatable in the tiebreaker.

Their first shootout was an eight-round marathon against the St. Louis Blues at Scottrade Center on October 27, 2016. Petr Mrazek gave up a goal to Alexander Steen in the first round but was perfect through the next seven. Gustav Nyquist scored in the second round for Detroit, and Henrik Zetterberg got the winner in the bottom of the eighth round for a 2–1 win.

The next two shootouts were also on the road, with Jimmy Howard in goal. Andreas Athanasiou scored the only goal in Philadelphia on November 8, and Thomas Vanek got the winner on November 23 at Buffalo.

The Red Wings improved to 5–0 with two more road wins in December. Vanek scored in the third round and Zetterberg in the fourth for a 4–3 win at Winnipeg, with Mrazek in goal, on December 6. Vanek scored again against the Florida Panthers 17 days later before Frans Nielsen got the deciding goal in another 4–3 win, this one with rookie Jared Coreau in goal.

The home fans finally got a look at the Red Wings’ shootout mastery on January 18. With Mrazek in goal, Vanek and Nielsen scored to give Detroit a 6–5 win against the Boston Bruins. Exactly one month later, Zetterberg scored his third game-deciding goal, this one in the fifth round, to give the Red Wings a 3–2 win against the Washington Capitals.

Nyquist scored the only goal and Mrazek didn’t allow one in three tries to give Detroit a 5–4 win against the Coyotes in Glendale, Arizona, on March 16. The Red Wings completed their 9–0 season in the shootout on April 3, when rookie Evgeny Svechnikov scored the only goal in a seven-round tiebreaker that gave Detroit a 5–4 victory against the Ottawa Senators in what proved to be the final shootout at Joe Louis Arena.

The final shootout tally for the 2016–17 season: The Red Wings were 6–0 on the road, 3–0 at home. Mrazek was 6–0, Howard 2–0 and Coreau 1–0. Zetterberg led the way with three game-deciding goals, and Nielsen had two. Mrazek’s .867 save percentage—four goals on 30 shots—was the best in the NHL among goaltenders who took part in more than three shootouts.

Those two goals by Nielsen were the only successes he had in eight attempts—the worst shootout season in his career. He signed with the Red Wings on July 2, 2016, after a decade with the New York Islanders during which he was 42-for-82 with 19 deciding goals, the most successful shooter in the history of the tiebreaker.

4 Nicklas Lidstrom has arguably been the NHL’s best defenseman during the past four decades (since the retirement of Bobby Orr). He won the Norris Trophy as the NHL’s top blueliner seven times, more than anyone other than Orr, and was a cornerstone of the Red Wings’ championship teams in 1997, 1998, 2002, and 2008. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2015, the first year he was eligible, and was named to the 100 Greatest NHL Players in 2017.

With credentials like that, you’d think Lidstrom would have been a first-round choice when he became eligible for the NHL draft, in 1989. But he wasn’t. In fact, he wasn’t taken in the second round either.

It was all due to a little bit of intrigue.

It seems the Red Wings had unearthed Lidstrom in Sweden but were desperate to keep their interest a secret in order to be able to pick him lower in the draft (try getting away with that today). The Wings had him targeted for the third round, the last one, at the time, in which 18 year olds could be drafted.

“The draft wasn’t as big as it is now,” Lidstrom told NHL.com. “My agent [Don Meehan] wanted to bring me over here and be part of the draft, but the Red Wings said they didn’t want anyone else to see that I was here, because someone else might pick me ahead of them. I was at home with my agent, and the Red Wings told me to wait by the phone, and they finally did pick me. Christer Rockstrom, who scouts for the Red Wings, scouted me.”

Neil Smith, who went on to build the New York Rangers’ Stanley Cup-winning team in 1994, was part of a trio of Detroit executives, along with Rockstrom and general manager Jim Devellano, who knew about Lidstrom. None of them was saying anything.

“He certainly wasn’t a physical killer,” Smith said years later. “He had a great understanding of the game. Nobody could beat him. Just think of a younger version of what you saw in the league all those years.”

The hard part was keeping the rest of the league from stealing Lidstrom away.

“I knew that if we didn’t take him in the third round this year, he’d go in the first round next year, because he’ll play in the World Junior [Championship] for Sweden and then everybody will know about him,” said Smith, who also pleaded with Meehan not to bring Lidstrom to the draft. Meehan complied, and the Red Wings got one of the all-time steals.

After taking center Mike Sillinger in the first round and defenseman Bob Boughner in the second, the Red Wings selected Lidstrom with the 11th selection (53rd overall) in the third round. Years later, Smith called it the best pick of his career. Given the results, it’s hard to argue with him.

5 The rejuvenation of the Red Wings began in the 1983 NHL Draft. Detroit had the fourth choice in the first round, and new general manager Jim Devellano, who had been hired after he’d helped Bill Torrey build the New York Islanders’ dynasty teams of the early 1980s, had his eye on a dynamic 18-year-old center named Pat LaFontaine.

Not only was LaFontaine a premier scorer, he’d grown up in Waterford, Michigan, and had played in the Detroit area before spending the 1982–83 season torching the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League while playing for Verdun. If ever there was a perfect match of player and team, this seemed to be it. Not only would the Red Wings get a future star, they’d get one who could help sell tickets at Joe Louis Arena, which was often half-empty back then.

The problem was getting the chance to take him. The Minnesota North Stars (now the Dallas Stars) had their eyes on US high-school star Brian Lawton with the No. 1 pick, but the Hartford Whalers, picking second, were regarded by many as likely to take LaFontaine with the No. 2 choice.

“I had approached the three teams ahead of me, asking what it would take to flip-flop picks,” Devellano said. But none of the teams ahead of the Red Wings was interested in dealing.

To the surprise of many, the Whalers took forward Sylvain Turgeon with the second choice. That left Devellano’s old team, the Islanders, next on the clock. The Islanders, coming off their fourth straight Stanley Cup championship, had fleeced the Colorado Rockies (who later moved to New Jersey) in a 1981 trade, dealing two spare parts—defenseman Bob Lorimer and forward Dave Cameron—for Colorado’s first-round pick in 1983. That turned out to be the third choice—and Torrey, Devellano’s old boss, decided that LaFontaine was just the player he needed to help keep the dynasty going.

However, Devellano didn’t go on to a Hall of Fame career by being unprepared. Though “Jimmy D” later admitted he’d have taken LaFontaine had he been available, he had a Plan B ready to go. That plan turned out to be Yzerman, a skinny, 175-pound center who had put up 91 points (42 goals, 49 assists) in 56 games for Peterborough of the Ontario Hockey League in 1982–83.

“We feel he can contribute right away,” Devellano said after the draft. “My only concern is that because of his age—he’s only 18—his strength is a question mark. But I think he’s gonna make it.”

6 Pavel Datsyuk arrived in Detroit just in time to grab No. 13.

Datsyuk was the 171st player taken in the 1998 NHL Draft, a kid from Sverdlovsk, Russia, who was allowed to mature in his home country by the talent-laden Red Wings until they brought him to North America in 2001.

That was just in time to nab No. 13, which had been left open by a trade that sent forward Vyacheslav Kozlov to the Buffalo Sabres as part of the package that brought goaltender Dominik Hasek to the Wings. Kozlov had been a two-time 30-goal scorer for the Red Wings and a valuable member of their Stanley Cup-winning teams in 1997 and 1998. But he’d scored just 18 goals in 1999–2000 and 20 in 2000–01, and the Wings deemed him expendable (partly because they knew that Datsyuk was in the pipeline).

Kozlov had worn No. 13 from the time he joined the Red Wings for seven games in the 1991–92 season, making him the third Detroit player to wear what many players deemed “unlucky No. 13.”

The first Red Wing to wear No. 13 didn’t do so for long.

Harold “Gizzy” Hart was a left wing who played for Detroit (then known as the Cougars) during 1926–27, the franchise’s inaugural season. He had spent the previous three seasons with the Victoria Cougars of the Western Hockey League and came to Detroit after the WHL went out of business.

Hart’s time with the Red Wings was short. After he went without a point in two games, Detroit sold Hart to the Montreal Canadiens on December 12, 1926. Hart played the rest of the 1926–27 season and all of 1927–28 with the Canadiens, returned to the minors with the Providence Reds from 1928 to 1932, and then returned to the Canadiens for 18 games in 1932–33. He went back to the minor league Reds until 1934, then spent his final career season of 1937–38 with the Southern Saskatchewan Senior Hockey League’s (SSSHL’s) Weyburn Beavers.

Hart was the only Red Wing to wear No. 13 until Kozlov did so in 1991.

7 Mike Modano was already the highest-scoring NHL player born in the United States when he came home to the Red Wings in 2010. Modano had played for Detroit Compuware in 1985–86, finishing with 66 goals and 131 points before going to spend three seasons with Prince Albert of the Western Hockey League. His 47-goal, 127-point season in 1987–88 attracted the attention of the Minnesota North Stars, who took him with the No. 1 pick in the 1988 NHL Draft.

Modano signed with the North Stars on Christmas Day in 1988, joined them for two playoff games in 1989, then became a full-time NHL player in 1989–90, finishing his rookie season with 29 goals and 75 points.

He became the face of the franchise after the North Stars became the Dallas Stars in 1993 and helped carry them to the Stanley Cup in 1999 (still the only Cup in that team’s history). He played all six games in the Final against the Buffalo Sabres despite a broken wrist sustained in Game 2. He had seven points (all assists) in the Final and led the Stars in the playoffs with 23 points.

But the Stars announced after the 2009–10 season that they wouldn’t re-sign Modano, and after deciding he wanted to continue playing, Modano signed a one-year contract with the Red Wings. The No. 9 he’s worn in Minnesota and Dallas had long since been retired in Detroit in honor of Gordie Howe, so Modano opted to wear No. 90.

Coach Mike Babcock planned to have Modano center the third line between Dan Cleary and Jiri Hudler. He got off to a sensational start, taking a pass from Cleary and scoring against the Anaheim Ducks at 5:35 of the first period in Detroit’s season opener on October 8, 2010, at Joe Louis Arena, sparking his new team to a 4–0 win. But Modano wound up being limited to 40 games during the 2010–11 season after a skate severed a tendon in his right wrist. He finished the season with four goals and 15 points, giving him 561 goals and 1,374 points in 1,499 regular-season games during 21 seasons. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in November 2014, and he was named to the 100 Greatest NHL Players in 2017.

8 Dave Lewis never spent a day in the minor leagues. He played 1,008 NHL games doing one of hockey’s most thankless jobs, being a defensive defenseman. Lewis never scored more than five goals or had more than 29 points in his 15 NHL seasons, the last two of which were spent with the Red Wings.

His playing career ended after he dressed for six games with Detroit during the 1987–88 season, but his involvement with the team didn’t. The Red Wings hired him as an assistant under coach Jacques Demers.

Lewis remained as an assistant after Bryan Murray took over as coach in 1990 and was kept when Scotty Bowman succeeded Murray in 1993. Lewis was promoted to associate coach in 1995, largely focusing on the defense, and was part of the Red Wings during their Stanley Cup-winning seasons in 1996–97, 1997–98, and 2001–02.

When Bowman called it a career after the Wings won the Cup in 2002, Lewis was the logical successor. He got the job on July 17, 2002.

The Red Wings had an excellent first season under Lewis, finishing first in the Central Division, second in the Western Conference, and third in the overall NHL standings at 48–20–10–4 (110 points). They appeared to have an excellent chance to repeat as Stanley Cup champions, only to run into the seventh-seeded Anaheim Ducks, who got a brilliant effort by goaltender Jean-Sebastian Giguere and swept the Western Conference Quarterfinal series in four games, one of the most stunning upsets in playoff history.

But Detroit showed no ill effects from the stunning playoff loss in 2003–04. The Red Wings went 48–21–11–2 that season, winning the Central Division again and finishing first in the NHL standings. This time, they got past the first round of the playoffs, defeating the pesky Nashville Predators in six games. But they came up short in the Western Conference Semifinals, losing to the Calgary Flames in six games. The series was tied 2–2 after four games, but Flames goaltender Miikka Kiprusoff made 31 saves in a 1–0 victory in Game 5 at Joe Louis Arena, and Calgary won, 1–0, in overtime in Game 6.

The lockout that shut down the NHL for the 2004–05 season spelled the end to Lewis’s coaching career in Detroit. His contract was allowed to run out on June 30, 2005, and he was rehired as a scout on August 9, 2005.

Lewis spent one season as a Wings scout before being hired as coach of the Boston Bruins in 2006, but he was let go after the Bruins went 35–41–6 in 2006–07 and missed the playoffs. Since then, he’s been an assistant with the Los Angeles Kings and Carolina Hurricanes, and he has coached the national teams of Ukraine and Belarus.

9 For all of Gordie Howe’s brilliance during his 25 seasons with the Red Wings, he never scored more than three goals in a single game. Mr. Hockey had 19 regular-season hat tricks and one in the Stanley Cup Playoffs on April 10, 1954.

He’d have had to combine two of those hat tricks to equal the performance that Syd Howe (no relation) had against the New York Rangers on February 3, 1944.

Less than two weeks after Syd scored three times against the lowly Rangers—they finished that season 6–39–5—in Detroit’s historic 15–0 win on January 23, 1944, he doubled that feat during the Red Wings’ 12–2 win at the Olympia.

In front of a crowd of 12,293, the Red Wings were already leading, 1–0, when Howe scored his 18th goal of the season, beating goaltender Ken McAuley at 11:27. His second goal of the night came 18 seconds later and gave the Red Wings a 3–0 lead after one period.

The game was still 3–0 late in the second period when Howe completed his seventh regular-season hat trick by scoring at 17:52. Goal number four came 62 seconds later, and Cully Simon scored with four seconds remaining in the period for a 6–0 lead.

After Mud Bruneteau made it 7–0 early in the third period, Howe struck for two more quick goals to complete his historic night. Don Grasso and Bruneteau each assisted, when Howe scored first at 8:17 and again at 9:14

“They were going in the net tonight,” said Howe, who was carried off the ice on the shoulders of his teammates. “I don’t remember any goal in particular. The boys were feeding them to me nicely.

“No celebration for me,” he added, according to the Detroit News, “I’m due at work at 7:10 a.m.”

Howe worked as a machinist at Ford Motor Company by day, playing center and left wing by night.

He became the first NHL player to score six goals in a game since Cy Denneny of the Ottawa Senators had done it on March 7, 1921. Only two players since Howe have scored six goals in a game: Red Berenson of the St. Louis Blues did it against the Philadelphia Flyers on November 7, 1968, and Darryl Sittler of the Toronto Maple Leafs scored six goals during his NHL record 10-point night against the Boston Bruins on February 7, 1976.

Oddly enough, Howe didn’t have the biggest offensive performance on the Red Wings that night. Grasso had one goal of his own and assisted on six others, including five by Howe, for seven points. Perhaps incredibly, Howe also scored all six of his goals without benefit of a power play; the Rangers didn’t take a penalty all night.

10 Game 7 of the Stanley Cup Final is one of the ultimate contests in any sport. Having the most important game of the season go into overtime ups the pressure exponentially.

Such a scenario had never happened from the time the NHL went to a best-of-seven format in the Final in 1939 until 1950, when the Red Wings played the New York Rangers.

On paper, it was a series that should never have gone to a seventh game. The Red Wings had run away with first place, finishing the 70-game season with 88 points—remember, there was no overtime or shootouts used to determine a winner if the game was tied after 60 minutes during that era—while the Rangers were a distant fourth with 67. But the Rangers upset the Montreal Canadiens in the Semifinals, winning in five games behind the goaltending of Chuck Rayner, who won the Hart Trophy as regular-season MVP. The Red Wings had to go seven games to eliminate the Toronto Maple Leafs and needed to win Games 6 (4–0 at Toronto) and 7 (1–0 at Detroit on an overtime goal by Leo Reise).

They’d lost Gordie Howe in Game 1, when Howe missed his check on Leafs center Ted “Teeder” Kennedy and went face-first into the boards. Howe was carried off the ice with a badly broken skull and didn’t play again until the following season. But in Detroit’s favor, the Rangers wouldn’t get to play a home game. With the circus taking over Madison Square Garden, the Rangers were the “home” team for Games 2 and 3 at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto, with all other games at the Olympia.

The series started according to form, with Detroit winning the opener, 4–1. The Rangers won, 3–1, in Game 2, but a 4–0 win in Game 3 sent the series back to Detroit with the Red Wings poised to close it out quickly. But that didn’t happen, largely thanks to Rayner and New York center Don Raleigh, who scored in overtime for a 3–2 win in Game 4, then did it again in OT for a 2–1 win in Game 5, becoming the first player to score back-to-back overtime goals in the Final in the process.

The Red Wings were on the ropes when the Rangers took 2–0 and 3–1 leads in Game 6, then fell behind again when Tony Leswick scored 1:54 into the third period to give New York a 4–3 lead. But Ted Lindsay scored less than three minutes later to get the Wings even, and Sid Abel’s goal midway through the third period stood up for a 5–4 win.

One night later, on April 23, 1950, the Red Wings again found themselves playing from behind, when New York scored two power-play goals in a 64-second span for a 2–0 lead after one period. Pete Babando and Abel scored power-play goals 21 seconds apart early in the second period to tie the game, and after Buddy O’Connor’s goal midway through the period put New York back in front, Jim Peters scored at 15:57 to get the Red Wings even at 3–3.

The goalies took over after that, with Rayner and Detroit’s Harry Lumley matching saves through a scoreless third period and a first 20-minute overtime.

Raleigh nearly got his third OT winner, but his shot hit the post. Not long afterward, George Gee won a faceoff back to Babando, whose backhander beat Rayner at 8:31 of the second overtime to give the Red Wings the Cup—and the longest Game 7 OT win in Final history.

“We were at a faceoff in their end to Rayner’s right,” Babando remembered in a 2000 interview with Mike Gibb of The Hockey News. “I was playing with Gerry Couture and George Gee, who took the faceoff. Usually, George had me stand behind him. But this time he moved me over to the right and told me he was going to pull it that way. I had to take one stride and get it on my backhand. I let the shot go, and it went in.”

Ironically, Leswick, who nearly cost the Red Wings the Cup in 1950, was their overtime hero four years later.

The Wings again were coming off a first-place season when they entered the 1954 Stanley Cup Playoffs. They had no problem polishing off the Maple Leafs in five games in the Semifinals and appeared ready to do the same in the Final against the Canadiens after winning Games 3 and 4 at the Forum. But with the packed house at the Olympia ready to celebrate, the Canadiens spoiled the party with a 1–0 win on an overtime goal by Ken Mosdell. Given new life, the Canadiens returned home and evened the series with a 4–1 win, with Floyd Curry scoring twice.

The full house at the Olympia for Game 7 on April 16, 1954, groaned when Curry scored midway through the first period to give the Canadiens a 1–0 lead. But Red Kelly tied the game, 1–1, at 1:17 of the second period by scoring a power-play goal.

After that, the goaltenders took over. Montreal’s Gerry McNeil and Detroit’s Terry Sawchuk were perfect through the rest of the second period and all of the third, sending Game 7 to overtime for the second time in four years.

Unlike the OT in the 1950 Final, this Game 7 ended quickly. Just over four minutes into overtime, Glen Skov carried the puck into the Montreal zone. The puck came to Leswick, who floated a long shot from near the right point toward the net.

It was a shot that McNeil normally would have handled easily. But Canadiens defenseman Doug Harvey tried to knock the puck down with his glove so he could play it; instead, he deflected the shot over McNeil’s shoulder and into the net at 4:29.

Incredibly, the hero of the night never saw the Cup-winning goal.

“I had the puck around center ice or so, and I just wanted to do the smart thing and throw it in. If I get caught with the puck and the Canadiens steal it, we may get caught and they may get an odd-man break,” Leswick remembered years later. “Just like that, the game could be over. So I’m just thinking of lifting the puck down deep in their end, just making the safe play. I flipped it in nice and high and turned to get off the ice. The next thing I know, everyone’s celebrating. It had gone in. I said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding. It went in? Get out of here!’”

The crowd was stunned, then erupted as they realized what had happened. Irvin and the Canadiens stormed off the ice, refusing the traditional end-of-series handshake line.

No Game 7 of the Final has gone to overtime since then.

11 The Red Wings had no trouble filling the penalty box during the 1985–86 season. Winning games was another matter.

Detroit took a mind-boggling 2,393 penalty minutes in 1985–86; that’s just under 30 minutes per game in an 80-game season. For perspective, the 2017–18 Red Wings played two more games but took a total of 710 penalty minutes, fewer than nine per game.

Joe Kocur led the 1985–86 Wings with 377 penalty minutes. No one else reached 200; however, nine other players took more than 100 minutes in penalties. Two of them (Warren Young and Gerard Gallant) each scored more than 20 goals despite taking more than 100 PIM.

But while the Philadelphia Flyers of the mid-1970s combined high penalty numbers with success in the standings, the 1985–86 Red Wings decidedly did not.

The Wings finished with a woeful record of 17–57–6; their 40 points were 14 fewer than the next-worst team (the Los Angeles Kings). The 57 losses are the most in franchise history.

Detroit had a losing record in every month except November, when the Red Wings went 5–5–2. They were 4–12 in games decided by one goal, and a mind-boggling 8–33 in games decided by three or more goals (meaning that more than half of Detroit’s games were blowouts by the NHL’s standard).

The parade to the penalty box was a big reason for Detroit’s inability to win. Detroit was short-handed 394 times and allowed a league-leading 111 power-play goals, another team record. Their 71.8 penalty-killing percentage was next to last in the NHL.

Put that together with a leaky defense at even strength, and the Red Wings ended up setting a dubious team record by allowing an NHL-worst 415 goals, 98 more than the NHL average that season. Combine with a league-low 266 goals scored, and it’s easy to see why Detroit came in 21st in a 21-team league.

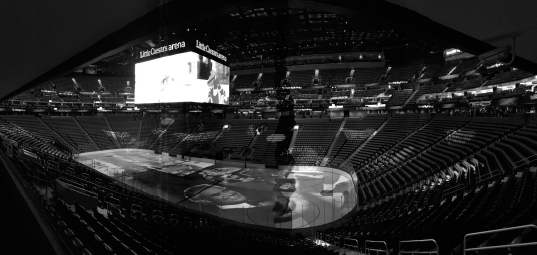

12 All good things must come to an end, and that included the Red Wings’ time at Joe Louis Arena. With the Wings missing the Stanley Cup Playoffs for the first time since 1990, it became obvious in the final weeks of the 2016–17 NHL season that their final game at “The Joe” would be April 9, 2017, when the New Jersey Devils came to town.

Rather than a wake, the Red Wings’ 4–1 victory was treated more like a party with 20,027 guests and one of the staples of Detroit hockey: The team website reported that 35 octopuses hit the ice during the final game.

The outcome was almost immaterial. Neither the Red Wings nor Devils had been close to the playoff race for weeks, but Detroit’s 4–1 win gave the fans one last chance to cheer.

“It was a perfect ending to an otherwise not-so-good season,” captain Henrik Zetterberg said. “When you picture the last game at the Joe—except if it would’ve been Game 7 of the Stanley Cup Final—this was very nice.”

Fans gave the Wings a standing ovation when they took the ice for warmups. Longtime star Steve Yzerman was cheered when he dropped the ceremonial first puck between Zetterberg and Devils captain Andy Greene.

“I thought it was a great building to play in,” Yzerman said. “Every time you stepped on the ice for a game, you were always excited to play the game. It just had a really nice atmosphere in there. It was beautiful in its simplicity.”

It was a doubly special night for Zetterberg, who was playing his 1,000th NHL game—all with the Red Wings.

“I’ve never had goose bumps that many times during a hockey game in my entire life,” said Zetterberg, who received a Rolex watch from the team in a pregame ceremony. “It was an incredible night.”

It was certainly a night that Detroit center Riley Sheahan would never forget. Sheahan came into the game having gone without a goal for the entire 2016–17 season, but he scored for the first time in exactly a year at 7:09 of the first period when he fired a wrist shot into the top of the net. Sheahan also had the honor of scoring the last goal in the arena’s history when he connected during a power play with 2:33 remaining in the third period.

“There are a lot of things I will remember about my career, and scoring the last goal here will definitely be one of them,” he said. “I’ll have that for the rest of my life.”

13 Terry Sawchuk and No. 1 were synonymous in Detroit during his first two stints with the Red Wings, 1949–50 through 1954–55 and 1957–58 through 1963–64. He had a goals-against average of less than 2.00 in each of his first five seasons with the Red Wings and wore the Winged Wheel for most of his Hall of Fame career.

But all good things come to an end, and the concept of retiring or honoring numbers wasn’t prevalent when Sawchuk was claimed by the Toronto Maple Leafs in the NHL intraleague draft on June 10, 1964. In fact, seven other players had worn that number—Glenn Hall for the two seasons that Sawchuk spent with the Boston Bruins (1955–56 and 1956–57) and six others for brief stints while they filled in for Sawchuk.

This was an era in which teams usually had an unquestioned starter in goal—and that player usually wore No. 1. Thus, after Sawchuk left for Toronto, the Red Wings wasted no time reissuing it. The recipient was Sawchuk’s replacement, Roger Crozier, who wore No. 1 from 1964–65 through 1969–70. Crozier even kept No. 1 when the Red Wings brought back Sawchuk for the 1968–69 season, with Sawchuk wearing No. 29.

Five players wore No. 1 during the next 10 seasons, with Jim Rutherford mostly owning it from 1974–75 through 1979–80 after wearing it briefly in 1970–71. Rutherford was still wearing No. 1 when he was traded to the Los Angeles Kings on March 10, 1981.

Gilles Gilbert, who had been wearing No. 30, switched to No. 1 when it became available, and he wore it until he retired after the 1982–83 season. Rutherford, who signed with Detroit for a last hurrah in the summer of 1982, wore No. 29 in his final appearance with the Wings.

Gilbert’s retirement left No. 1 available for Corrado Micalef, who wore it for the next three seasons. But Micalef was demoted to the minors after going 1–9–1 during the 1985–86 season. The Red Wings acquired Glen Hanlon in a trade with the New York Rangers on July 29, 1986, and Hanlon wore No. 1 during his five seasons in Detroit before retiring after the 1990–91 season.

Hanlon was the last of 10 players to wear No. 1 after Sawchuk’s departure in 1964. No. 1 was taken out of circulation until it was officially retired in March 1994.

14 Who says you can’t get much for a buck? The Red Wings got a four-time Stanley Cup-winning center for a measly one-dollar bill.

Kris Draper had been a third-round pick (No. 62) by the Winnipeg Jets in the 1989 NHL Draft, but hadn’t been able to stick while playing pieces of three seasons with the Jets from 1990–93. He had three points, all goals, in 20 games and spent most of that time with the Moncton Hawks of the American Hockey League.

But proving that one team’s trash is another team’s treasure, the Red Wings saw something in Draper the Jets hadn’t. On June 30, 1993, the Wings acquired him from the Jets for what were called “future considerations,” something that actually proved to be worth less than the price of a cup of coffee.

Not in their wildest dreams could the Red Wings have hoped to get a player who would play for them for the next 17 seasons and become a regular on four championship teams.

Draper became a fixture on what became known as the “Grind Line,” skating between Darren McCarty and Joe Kocur (later Kirk Maltby) on a ferocious checking unit that did a lot of the dirty work that title-winning teams need. Perhaps their best work came in the 1997 Stanley Cup Final, when the trio of Draper, McCarty, and Maltby shut down the Philadelphia Flyers’ “Legion of Doom” line during Detroit’s four-game sweep. With the Grind Line doing most of the heavy lifting, the Red Wings limited 50-goal scorer John LeClair to two goals and star center Eric Lindros to one (he scored with 15 seconds left in Game 4).

Kris Draper became a four-time Stanley Cup winner with the Red Wings. (By Dan4th Nicholas—080202 red wings at bruins (369), License: CC BY 2.0, Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4833774)

“It was such a huge honor and a huge thrill for us to be able to be put in those situations,” Draper told NHL.com in 2013. “Whether you’re playing against Lindros, playing against [Peter] Forsberg or [Joe] Sakic, or playing against [Mike] Modano, we took a lot of pride in that. We also felt that we could chip in with some goals offensively. That was something we were able to do.

“We were going to play. We were going to play hard. We were going to compete and felt that we could do some good things.”

Draper even became an offensive contributor, although it’s somewhat ironic that his best offensive season, 2003–04, with career highs of 24 goals and 40 points, ended with him being recognized with the Selke Trophy, an award given to the NHL’s best defensive forward.

Draper was still contributing in 2008, when he helped the Red Wings win the Cup for the fourth time in 12 years. He retired after the 2010–11 season, having played 1,137 games with the Red Wings and contributing 361 points (158 goals, 203 assists).

That’s a lot of bang for a buck!

A few months after the Red Wings won the Cup in 1997, Draper gave owner Mike Ilitch and his wife, Marian, a personal token of his appreciation.

“I was able to give Mr. and Mrs. Ilitch the dollar back, so I’d like to think that we’re even,” Draper told NHL.com. “Who would have thought that number one, a player was going to be traded for a dollar, and then certainly I’m real proud of everything that went on and all the proud moments I had within the organization.”

15 It seems so logical now, but it took a Hall of Fame coach, Scotty Bowman, to put the Red Wings’ five Russian players together on the ice at the same time.

Actually, what Bowman did was pretty much standard operating procedure back in Russia, going back to the days of the Soviet Union, when five-man units were common. That practice was almost unheard of in North America, where forward lines were, and generally still are, mixed with different defensive pairings.

On October 26, 1995, the “Russian Five” quintet of forwards Sergei Fedorov, Igor Larionov, and Vyacheslav Kozlov and defensemen Vladimir Konstantinov and Viacheslav Fetisov made its debut against the Calgary Flames and helped the Red Wings score two of their three goals—one each by Kozlov and Larionov—in a 3–0 victory.

“My main trick was not to unite all five Russians every time,” Bowman told NHL.com in 2015. “I was worried that the opponents would be able to figure out how to play against them. Often, I would wait until the second or even third period to get them out on the ice together. It always got other teams confused.”

The Red Wings already had Fedorov, Kozlov, and the two defensemen when they made what seemed to be an odd trade early in the 1995–96 season, sending right wing Ray Sheppard, who had scored 150 goals for Detroit in the previous four seasons, to the San Jose Sharks for Larionov, then 34. Though Larionov had been a star in the USSR, he hadn’t put up big scoring numbers after being allowed to come to the NHL and joining the Vancouver Canucks in 1989.

But Bowman knew what he was doing.

“At that time, we had too many right wings,” Bowman said. “The Sharks gave me a massive list of players to choose from in exchange for Sheppard. I wasn’t looking for a center, but when I saw Larionov’s name, I thought that it would be great to get a player with such enormous hockey IQ and put all five Russian guys together.”

Larionov’s nickname, “The Professor,” was an indicator that he had the hockey IQ Bowman was looking for.

The Russian Five didn’t play the dump-and-chase style that most NHL teams used. They relied on their speed and puck control. The wings, Fedorov (who switched from center when Larionov arrived) and Kozlov, would often switch sides. That helped create more scoring chances, because many opponents didn’t know how to play against them.

“I remember Larionov and his linemates always saying that if you have the puck, you control the game,” Ken Holland, then Detroit’s assistant general manager, told NHL.com. “They came from the same school of hockey and shared a similar mentality. They understood each other perfectly.”

Each of the five Russians added something special. Fedorov, who in 1994 had become the first player born in Europe to win the Hart Trophy, had dazzling speed and skill, making him a threat to score any time he was on the ice. Kozlov was a terrific passer with a big slap shot. Larionov was one of the great playmakers in hockey history, Konstantinov provided a physical element and solid defensive play, and while Fetisov was no longer the world’s best defenseman, he was still terrific in his own zone and had excellent offensive skills.

With the five Russians playing mostly as one unit, the Red Wings set an NHL record for victories in 1995–96 by winning 62 games. In 1996–97, they were a key to Detroit’s first Stanley Cup championship since 1955.

“When the Russian Five were on the ice, you had to have your popcorn ready, because you knew that you were in for a treat,” Bowman said. “They didn’t just play hockey, they created masterpieces on the ice.”

Pavel Datsyuk came along after the “Russian Five” era. The Red Wings selected him in the sixth round (No. 151) of the 1998 NHL Draft. But they didn’t bring him to Detroit until the 2001–02 season, just in time to be part of another Stanley Cup-winning team.

16 After going 42 years without winning the Stanley Cup, the Red Wings won back-to-back titles in 1997 and 1998—and they swept the Final each time. The Red Wings were a definite underdog as they prepared for the first game of the 1997 Stanley Cup Final against the Philadelphia Flyers. The 1996–97 team had plummeted from 131 points in 1995–96 to 94 and a second-place finish in the Central Division behind the Dallas Stars.

But the first three rounds of the playoffs were another story. After losing, 2–0, in the opener of their Western Conference Quarterfinal series against the St. Louis Blues, the Wings won four of the next five games. That was followed by a sweep of the Mighty Ducks of Anaheim in the conference semifinals, and a bitterly fought six-game win against the Colorado Avalanche in the conference final just one year after the Avs had defeated them in the same round on their way to winning the 1996 Stanley Cup.

The Flyers breezed through their first three rounds, eliminating the Pittsburgh Penguins, Buffalo Sabres, and New York Rangers in five games apiece behind the “Legion of Doom.” The line of center Eric Lindros between left wing John LeClair and right wing Mikael Renberg terrorized opponents with their combination of size and skill. Lindros, in particular, had excelled against the Rangers, dominating New York’s defense and making 36-year-old Mark Messier look his age.

In the run-up to the series opener on May 31 at Core States Center (now Wells Fargo Center), the question was how the Wings would cope with Lindros and his linemates. The Red Wings didn’t have the kind of size, especially on defense, they were expected to need.

Still, there’s more than one way to ground a Flyer. Instead of trying to match muscle with muscle, coach Scotty Bowman decided to defuse Philadelphia with skill. The pairing of Nicklas Lidstrom and Larry Murphy wasn’t going to outmuscle anyone, but their combined skills helped defuse Philadelphia’s big line.

The Red Wings stunned the packed house of 20,291 by winning the opener, 4–2. Lindros had two assists, one on a goal by LeClair, but Joe Kocur’s unassisted goal late in the series put Detroit ahead to stay. Sergei Fedorov and Steve Yzerman each scored, and Mike Vernon made 26 saves.

Three nights later, the Red Wings quieted a crowd of more than 20,000 with another 4–2 win. Kirk Maltby broke a 2–2 tie in the second period and Brendan Shanahan scored his second goal of the game midway through the third. Vernon was sharp again, making 29 saves.

The crowd of 19,983 that packed Joe Louis Arena for Game 3 on June 5 undoubtedly was thinking of a sweep. LeClair’s power-play goal 7:03 into the game dampened the atmosphere, but only briefly. Yzerman tied the game two minutes later, Fedorov and Martin Lapointe made it 3–1 before the end of the period, and the Wings cruised to a 6–1 win and a 3–0 series lead.

Philadelphia played with desperation in Game 4, but the Wings were just too much for them. Lidstrom put Detroit ahead at 19:27 of the first period, and Darren McCarty’s goal 3:02 into the second made it 2–0. Vernon was 15 seconds from a shutout in the clincher when Lindros scored his only goal of the series, but it was too little, too late. The 2–1 win gave the Red Wings a sweep and their first Cup in 42 years.

In contrast, the Wings were heavy favorites to keep the Cup in 1998. They had defeated the Phoenix Coyotes, St. Louis Blues, and Dallas Stars in six games each, and their opponent in the Final was the Washington Capitals, who had finished fourth in the Eastern Conference but got an easy path to the first Stanley Cup Final in franchise history when the two division winners in the East, the Pittsburgh Penguins and New Jersey Devils, were upset in the first round of the playoffs.

The Red Wings won, 2–1, in the opener at Joe Louis Arena. Lidstrom and Kocur scored in the first period. Richard Zednik’s second-period goal was the only one of Washington’s 17 shots to beat goalie Chris Osgood.

Washington led, 3–1, after two periods in Game 2 and was ahead, 4–2, with less than 12 minutes left in the third period. But goals by Lapointe and Doug Brown forced overtime, and Kris Draper beat Olaf Kolzig at 15:24 of OT for a 5–4 win.

Fedorov’s goal at 15:09 of the third period gave the Red Wings a 2–1 win in Game 3, and Brown scored two goals in Detroit’s 4–1 win in Game 4, making Detroit the first (and still only) team since the New York Islanders in 1982–83 to sweep the Final in back-to-back years.

17 Following a sweep by the New Jersey Devils in the 1995 Stanley Cup Final and coming up short in 1996 after setting an NHL regular-season record for victories, the Red Wings knew they had to make some changes.

The Wings decided they wanted Brendan Shanahan, a high-scoring power forward who’d had two 50-goal seasons and scored 44 goals for the Hartford Whalers in 1995–96 despite playing with a sore wrist. Shanahan had made it clear he wanted out of Hartford, but future Hall of Famers don’t come cheap, and the Whalers weren’t going to give him Shanahan away, no matter how much he wanted to leave.

On October 9, 1996, the Red Wings got their man, acquiring Shanahan and defenseman Brian Glynn from the Whalers. But Shanahan didn’t come cheap: The Red Wings had to send center Keith Primeau and a first-round draft pick to the Whalers, along with another future Hall of Famer, defenseman Paul Coffey.

Not that Coffey, who had won the Stanley Cup three times with the Edmonton Oilers and one with the Pittsburgh Penguins, was dying to leave Detroit.

Coffey, 37, didn’t want to leave a potential Cup-winning team near the end of his stellar career to go to the Whalers. He was benched by coach Scotty Bowman for the Wings’ 1996 season opener at New Jersey and paid for his own plane ride home.

Bowman told Mitch Albom of the Detroit Free Press that Coffey attempted to negate the deal with two phone calls, one to Primeau, who Coffey instructed to refuse a trade, and a second to Whalers general manager Jim Rutherford, to express his displeasure and reluctance to play in Hartford. Coffey denied the charges.

According to the Hartford Courant, Bowman never told Coffey about the trade—the defenseman learned about it from the sad expression of a Wings assistant equipment manager.

“He did some things … probably to hurt me or whatever,” Coffey said about Bowman to the Courant. “He made it as difficult as possible.

“But anybody that has ever known me will say that I don’t look to knock people to make myself look better. For me to take shots at anybody would be a very insecure thing, and I’m not like that. It’s just not worth it.

“The way this was handled was very disappointing.”

Coffey joined the Whalers for the 1996–97 season. But after 20 games, he found himself traded once again—to the Philadelphia Flyers. After stints with the Chicago Blackhawks and the Carolina Hurricanes, Coffey played his final season, 2000–01, with the Boston Bruins. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2004, and his No. 7 was retired by the Oilers the next year.

Shanahan’s arrival proved to be the missing piece. He played nine seasons and 716 games with the Wings, scoring 309 goals and adding 324 assists for 633 points. Shanahan played on the Cup-winning teams in 1997, 1998, and 2002, scoring 22 goals (including six game-winners) and adding 23 assists.

“It was a catalyst for our team,” Bowman told the Edmonton Journal. “He was a big-game player. In the playoffs, he could get to the stage.”

18 Gordie Howe didn’t win as many NHL scoring titles as Wayne Gretzky, but not even the Great One managed as many top-five finishes as Mr. Hockey.

From 1949–50, when he was third in the NHL with 68 points, though 1968–69, when he was third again, with 103 points, Howe was never out of the top five.

That 20-season streak began when Howe came in third behind linemates Ted Lindsay (78 points) and Sid Abel (69) in 1949–50, his fourth NHL season. It marked the first time that linemates had finished 1–2–3 in the scoring race.

For the next four seasons, Howe took custody of the Art Ross Trophy. He led the NHL in 1950–51 with 86 points and had the same number with the same result in 1951–52. Howe bumped that total up to 95 points in 1952–53, finishing 24 points ahead of runner-up Lindsay and cruising to his third straight scoring title. He had “only” 81 points in 1953–54, but that was still 14 more than runner-up Maurice Richard of the Montreal Canadiens.

Howe dropped to 62 points in 64 games in 1954–55, falling to fifth in the scoring race. He also failed to lead the Wings in scoring for the first time since 1949–50, finishing four points behind Dutch Reibel.

Howe was back up to 79 points in 1955–56, finishing second in the NHL to Montreal’s Jean Beliveau. But he won the Art Ross Trophy again in 1956–57 with 89 points, finishing four ahead of Lindsay.

For the next five seasons, Howe was remarkably consistent. He finished with anywhere from 72 to 78 points and came in fifth (twice), fourth (twice), and third (once) in the scoring race. In 1962–63, Howe was back on top with 86 points, five more than Andy Bathgate of the New York Rangers.

For the final four seasons of the Original Six era, Howe was among the NHL’s most consistent scorers, finishing fifth, third, fifth, and fourth. He followed a 65-point season in 1966–67, the last of the six-team NHL, by piling up 82 points in 1967–68, the first season after the NHL expanded to 12 teams. That was good enough for a third-place finish.

With offense on the rise, Howe’s 103-point season in 1968–69 was only good for third behind Phil Esposito of the Boston Bruins (126) and Bobby Hull of the Chicago Black Hawks (107). Then again, each was a lot younger than Howe, who turned 41 late in the season.

Howe finally fell out of the top five in 1969–70, when he finished with 71 points (31 goals, 40 assists) in 76 games. But though he finished ninth in the scoring race, he was still voted an NHL First-Team All-Star for the final time.

Injuries finally caught up to Howe in 1970–71, his final season with the Red Wings, when he had 23 goals and 52 points in 63 games. He retired from the Red Wings after that, only to return to hockey in 1973 with Houston of the World Hockey Association.

19 Gordie Howe scored 786 goals during his Hall of Fame career with the Red Wings. He was the first player in NHL history to score 600, 700, and (with the Hartford Whalers in 1979–80) 800 goals.

Four more players—Phil Esposito, Marcel Dionne, Wayne Gretzky, and Mike Gartner—followed Howe into the 700-goal club. Dionne, who played his first four seasons in Detroit, was the only one of the four who had spent any time with the Red Wings.

Then, on February 10, 2003, Brett Hull joined Howe as the only two players who scored their 700th NHL goals with the Red Wings.

Hull, whose father Bobby Hull scored 610 NHL goals, came into the Red Wings’ game against the San Jose Sharks at Joe Louis Arena with 699 goals, a number he’d been stuck on for seven games. The drought finally ended at 16:54 of the second period, when Hull took a cross-ice pass from Pavel Datsyuk and one-timed a shot past goaltender Evgeni Nabokov for the milestone goal.

Hull had a big smile on his face as his teammates jumped off the bench to celebrate with him. When asked if his accomplishment had sunk in yet, Hull said, “I think so. It’s been seven games, so I think it has.”

The goal put Detroit ahead, 3–2, in a game that went back and forth until Patrick Boileau beat Nabokov with a high shot from the right circle for his second NHL goal with 2:37 remaining in the third period to give the Red Wings a 5–4 win.

“I’m only 698 behind,” joked Boileau, a journeyman who had spent most of the season with Grand Rapids of the American Hockey League.

That victory ended a six-game winless streak for the Red Wings and left Hull in an even happier mood.

“It’s big that we won,” Hull said. “The last thing I wanted to do was get this goal down 4–0. I wanted it to be in a win.”

20 What could be better than having a future Hockey Hall of Famer like Nicklas Lidstrom on defense? How about a Hall of Fame partner?

No one realized it at the time, but that’s what ultimately happened when the Red Wings acquired Larry Murphy from the Toronto Maple Leafs on March 18, 1997.

Murphy, an excellent puck mover, had helped the Pittsburgh Penguins win the Stanley Cup in 1991 and 1992. The Toronto Maple Leafs thought he’d be a great addition to their team when they acquired him from the Penguins in July 1995; Murphy was coming off a season in which he’d been named an NHL Second-Team All-Star and finished fourth in balloting for the Norris Trophy.

But Murphy and the Maple Leafs weren’t exactly a match made in hockey heaven. After a third-place finish in the Central Division and a first-round loss in the playoffs in 1995–96, the Leafs fell apart in 1996–97—and Murphy took a lot of the blame. The boos rained down on a nightly basis at Maple Leaf Gardens, and Murphy took plenty of heat as the team plummeted to the bottom of the division.

By trade deadline time, the Leafs were looking to cut their losses. Meanwhile, the Red Wings wanted another defenseman who could move the puck and take some of the load off Lidstrom. That man was Murphy, who came to Detroit for the ever-popular “future considerations.”

One big reason Murphy wound up in Hockeytown was that Scotty Bowman, who had coached him in Pittsburgh, pushed for the deal. The reunion revitalized Murphy’s career.

“I had a great experience with Scotty in Pittsburgh. That was a big factor,” Murphy told NHL.com in 2011. “I believed the team had a great chance to win the Cup, because Scotty was the coach. I knew what to expect going into it.”

Murphy had six points (two goals, four assists) for the Wings in the regular season after the trade. But he hit his stride in the postseason, leading all Detroit defensemen with 11 points and topping all players with a plus-16 rating.

It didn’t happen right away, but the combination of Murphy and Lidstrom made beautiful music together.

“For a time there, Scotty had me playing with [center] Sergei Fedorov as my partner after he moved him back to defense,” Murphy told NHL.com. “When he moved Sergei back to forward, he put me with Nick. At that time, I had heard about what a good player Nick Lidstrom was, but at that point in his career he wasn’t as well-known as he is now. It didn’t take very long to see what a great player he was. I was very fortunate to have him as a partner. He was probably the easiest partner I ever played with, because he was so reliable and so dependable. You just knew where he was going to be, and you could always count on him.”

With Lidstrom and Murphy as their top defensive pair, the Red Wings rolled to the Cup in 1997, sweeping the Philadelphia Flyers in the Final.

Murphy had 11 goals and 52 points for Detroit in 1997–98 and was plus-35. The Red Wings won the Cup again in 1998.

Murphy spent most of his time in Detroit as Lidstrom’s partner before retiring in 2001. The two are together now in the Hockey Hall of Fame.

“For me, it was a tremendous opportunity playing with a guy like that,” Murphy told MLive.com in 2012. “Reliable, Mr. Consistent, he was the perfect defense partner. … People that know the game know just how great he was. He wasn’t a guy that was out there for the flash, he wasn’t putting a show on for anybody, he was just going out there and getting the job done.”

21 Detroit was the center of automobile production in the United States after World War II, so when the Red Wings’ new coach, Tommy Ivan, replaced Jack Adams in 1947 and put two youngsters, left wing Ted Lindsay and right wing Gordie Howe, on the flanks with veteran center Sid Abel, “The Production Line” was born.

Abel was nearing the end of a career that would see him earn induction into the Hockey Hall of Fame. But Ivan felt putting him with a pair of younger, faster wings would provide a perfect blend of speed, skill and smarts.

How right he turned out to be!

In an era when goalies almost never came out of their crease to play the puck, the Red Wings adopted the strategy of having Howe and Lindsay dump the puck into the zone and angle it so the other one would be able to play the carom. (This worked especially well at the Olympia, where the home-ice advantage included very lively boards that were angled so that dump-ins usually kicked out toward the slot.)

The threesome led the Wings in scoring in 1947–48 and helped the Red Wings advance to the Stanley Cup Final, although they lost to the Toronto Maple Leafs. By 1949–50, they were 1–2–3 in the NHL in scoring—a feat that has never been repeated—and this time they powered the Red Wings to the Cup.

The trio’s success brought the need for a catchy nickname. “The Production Line” captured their scoring prowess as well as referencing the city where the Red Wings played.

The original “Production Line” stayed together until Abel was traded in 1952, but when Alex Delvecchio took over in the middle, “Production Line II” continued to make life miserable for opposing defenses. The latter trio stayed together until Lindsay was traded to Chicago after the 1956–57 season.

22 It’s hard to picture a hockey player who was all of 5-foot-8 and 165 pounds earning the nickname “Terrible Ted.” Then again, Ted Lindsay was no ordinary player.

Lindsay was a fascinating combination of talents, at once a skilled scorer who was the left wing on a team that won the Stanley Cup four times in six seasons, but also a player who would fight, could hold his own in the corners and spent more time in the penalty box than any star player of his generation.

“I hated everybody. I had no friends,” Lindsay told NHL.com in 2016 when asked about his ferocious approach to the game. “I wasn’t there to make friends. I was there to win. It wasn’t necessary that I score, but I figured I could be an integral part without scoring. I had ability, I had talent, and I didn’t have an ego that I thought I was great. I realized I had to earn it. That was my purpose—to be the best that there was at the left-wing position.

“I never looked at stats. I was part of a team. I couldn’t do it by myself and nobody else on the team could do it themselves. We were part of a team. I had to help my teammates as much as they helped me. That was my philosophy.”

Lindsay loved you if you wore the same jersey he did. If not…

“My hatred was sincere,” he said. “I liked to see [my opponents] dead. That was my problem, I guess. I understood people, understood human nature. I wasn’t a psychologist or anything, but I knew people. You’d figure out who the chickens were on the other side, who the bulls were on the other side, [then] spend your time with the chickens and stay away from the bulls.”

The rivalries between the Original Six teams were real. Teams played each other 12, and later 14, times per season, often home-and-home on Saturday and Sunday. There was no players union, no fraternization among opposing players. Players who fought one night often saw each other again 24 hours later.

“You never had to get him that night, that month, even that season,” Lindsay told NHL.com of avenging a slight from an opponent. “If he got you dirty … I never got people dirty, [but] I’d get ya.

“I never would purposely try to injure anybody. But I’d purposely try to get you out of the game if I could … intimidate you. When Lindsay comes on the ice, where is he? That’s the way I wanted him to think. When I came on the ice, Where the hell is he?

“I loved the corners. That’s where you found men. You found more chickens. You knew who the chickens were on the other team, because they’d always back off a little bit. If I was coming, they knew they were going to get lumber or elbows or anything. They were going to get into the screen [before there was glass].”

Toronto newspapers nicknamed him “Terrible Ted,” and, later, “Scarface.” That never bothered him.

“I was there to win,” he said. “If it meant taking you to the boards or whatever it was, intimidation would be the best way to do it.

“Everything was fun. I couldn’t wait until the next game. Some nights I was so good, but some nights I was so bad, I couldn’t wait until the next game to prove I wasn’t that bad. It was personal within me, I didn’t talk to anybody about it. I knew what my capabilities were. I didn’t need a coach to get me up, I was up for everybody.”

The funny thing was that away from the ice, Lindsay was anything but terrible. He has raised millions of dollars for charities and is beloved within hockey circles and around the Detroit area.

“I represent my family, my mom and dad,” he told NHL.com. “They gave me a proper upbringing, and I’ve tried to follow that all my life. I’ve kept my nose clean, as much as I could.” He laughed, the interviewer said, and added, “Away from the ice.”

23 Billy Smith of the New York Islanders was the first NHL goaltender to be credited with scoring a goal. Smith made a save during a delayed penalty against the Colorado Rockies on November 28, 1979. Colorado defenseman Rob Ramage picked up the rebound and back-passed it into his own net. Smith, the last player to touch the puck, was credited with the goal.

Ron Hextall of the Philadelphia Flyers became the first goaltender to score a goal by shooting the puck into the net when he scaled the puck into an empty net against the Boston Bruins on December 8, 1987. Hextall also became the first NHL goaltender to score a goal during a Stanley Cup Playoff game, when he shot the puck into the empty net against the Washington Capitals on April 11, 1989.

No goaltender scored again until March 6, 1996, when Chris Osgood of the Red Wings did it against the Hartford Whalers.

Like Hextall, Osgood did the deed himself. With time running out and the Red Wings leading, 3–2, at the Hartford Civic Center, Osgood corralled a shot and, instead of putting the puck behind the net or into the corner, dropped it to the ice. In one quick move, he took a shot up the middle of the ice. No Whaler came close to touching the puck (though a teammate nearly got hit in the face) before it nestled into the net, wrapping up a 4–2 victory

“It was great, I was really excited,” Osgood said after his league-leading 32nd victory. “In juniors, I used to take shots all the time, but here I usually pass it off to a defenseman. When we got the empty net this time, I said I was going to go for it.”

Said Red Wings coach Scotty Bowman, “I’ve never seen that play live in all my years. I have never had it happen to me in nearly 2,000 games.”

Osgood did more than just score a goal that season. He had one of the greatest seasons by a goaltender in NHL history, going 39–6–5 with a 2.11 goals-against average for a Detroit team that finished with 62 victories and finished first in the overall standings.

Though it was Osgood’s first and only NHL goal, it wasn’t the first one he’d ever scored in a game. While playing in juniors with Medicine Hat of the Western Hockey League, Osgood scored a goal on January 3, 1991.

24 The Red Wings were a dynasty in the early 1950s and one of the NHL’s most consistent teams through the 1960s, then hit the skids in the 1970s and early 1980s. They qualified for the Stanley Cup Playoffs once from 1971 to 1983 and finished above .500 only once during that span.

It’s easy to forget now that, in those days, the Red Wings were a mess on and off the ice. The nickname “Dead Things” had become attached to the Wings, whose season ticket base in the new, 20,000-seat Joe Louis Arena was down to about 2,100.

Happily for those fans who remained, Mike Ilitch came along.

Ilitch had played minor-league baseball before his hopes for a big-league career were derailed by a knee injury. He went into the pizza business in the Detroit area and thrived; eventually, his Little Caesars chain became one of the biggest in the country.

Joe Louis Arena was the home of the Red Wings from December 1979 to April 2017. (Schmackity [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or License: CC-BY-SA-3.0; Source: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/], from Wikimedia Commons)

But Ilitch never lost his love for sports, or for Detroit. On June 3, 1982, he combined the two when he and his wife, Marian, bought the Red Wings from Bruce Norris, whose family had run the team for 50 years. The New York Times estimated the price at $10 million to $12 million. Later reports pegged it at $8 or $9 million.

Success was anything but immediate. The Red Wings missed the playoffs in 1982–83 and were 18th in the 21-team league. But the first big on-ice piece of the team’s transformation came in June 1983, when the Red Wings selected center Steve Yzerman with the fourth pick in the NHL draft.

It took some time, but by the late 1980s, general manager Jim Devellano, one of the key members of the front office that built the New York Islanders’ dynasty in the 1980s, was beginning to put the pieces of one of the NHL’s great teams in place.

Unlike his business interests, Ilitch ran the Red Wings with the pure goal of winning championships. If that meant overspending, so be it. He believed in hiring good people and letting them do their jobs. The payoff was four Stanley Cup championships from 1996–97 through 2007–08, a 25-season run of Stanley Cup Playoff berths—and sellout crowds at The Joe and the new Little Caesars Arena.

In 2006, Kevin Allen and Art Regner teamed to write a book about Red Wings history, What it Means to Be a Red Wing. The Ilitches wrote the introduction, which concluded:

If you ask us what it means to be a Red Wing, we would say it means that everyone in the organization strives for success while conducting himself, or herself, in a classy and professional manner. It’s about pride. Little Caesars is a family business. And the Detroit Red Wings are a family organization. Pride has played an important role in the success of each venture.

25 The Red Wings hadn’t been good for a long time when Mike and Marian Ilitch bought the team from Bruce Norris, whose family had owned the franchise for a half-century. The organization was a mess. Coaches and general managers had come and gone for more than a decade, but while the names changed, the results were largely the same.

Luckily for the Red Wings, the Ilitches found the right man to resurrect the team.

Jim Devellano was Bill Torrey’s right-hand man with the New York Islanders, helping to turn a team that set NHL records for futility in 1972–73, its first NHL season, into a dynasty that won the Stanley Cup four straight times from 1980 to 1983.

But Devellano wasn’t there for the last Cup. He was the first person hired after the Ilitches bought the team. The 2018–19 season is his 37th with the Wings; according to the team, he’s the longest-serving hockey employee in the franchise’s 90-plus years in the NHL.

Devellano, a Toronto native, hadn’t played pro hockey. But he’d become a scout with the St. Louis Blues in 1967, when the NHL expanded from six to 12 teams. He joined the Islanders when they were added to the NHL in 1972 and scouted most of the players who became the core of one of the greatest dynasties in any sport. He also urged GM Bill Torrey to hire one of his former players in St. Louis, Al Arbour, as coach after that dreadful first season. Arbour coached the Islanders to all four championships.

In 1979–80, Devellano became general manager of the Islanders’ Indianapolis farm club in the Central Hockey League and was named Minor League Executive of the Year by The Hockey News. He returned to New York in 1981 as the Islanders’ assistant general manager.

That resume was more than enough to attract the interest of the Ilitches. He was hired as general manager and served in that capacity for eight seasons before being named senior vice president in 1990.

Devellano was one of the first NHL general managers to assemble a strong European scouting staff, a move that produced several Red Wings standouts, including Russians Sergei Fedorov, Slava Kozlov, Vladimir Konstantinov, and Pavel Datsyuk, as well as Swedes Nicklas Lidstrom, Tomas Holmstrom, Henrik Zetterberg, Johan Franzen, and Niklas Kronwall.

During Devellano’s tenure, the Red Wings have participated in 10 conference finals (1987–88, 1995–98, 2002, and 2007–09) and six Stanley Cup Finals (1995, ’97, ’98, ’02, ’08, and 2009), winning four. They won the Presidents’ Trophy six times (1995, ’96, 2002, ’04, ’06, and 2008), took home the regular-season Western Conference championship eight times (1994-96, 2002, ’04, and 2006–08), and won 16 division championships (1988–89, ’92, 1994–96, ’99, 2001–04, 2006–09, and 2011).

Devellano received the Lester Patrick Award for his outstanding service to the sport of hockey in the United States in October 2009. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in the Builder Category on November 8, 2010.

26 The Red Wings have had a variety of farm teams, beginning with the Detroit Olympics of the International Hockey League in 1932. Those teams have ranged from the East Coast (Baltimore Clippers of the American Hockey League), to the West Coast (San Diego Gulls of the Western Hockey League), and plenty of places in between.

Most of the affiliations lasted just a few years, though some had multiple stints. Others, like the current affiliation with the Grand Rapids Griffins of the AHL, have lasted well over a decade. But the longest-tenured affiliation came with one of the smallest market teams: The Adirondack Red Wings, based in Glens Falls, New York, from 1979 to 1999.

Ned Harkness, the former coach and general manager of the Red Wings, had become the director of the new Glens Falls Civic Center and persuaded owner Bruce Norris to move the Wings’ primary development team from Kansas City of the Central Hockey League to Glens Falls, where there was an AHL team that became known as the Adirondack Red Wings.

The new affiliate dressed like the parent team and was a hit from the start, routinely packing the Civic Center. On-ice success came quickly. Led by longtime NHL star Peter Mahovlich, Adirondack won the Calder Cup (the AHL version of the Stanley Cup) in 1980–81, just their second season in Glens Falls, and took home three more titles in the following 11 seasons.

Player turnover is a given in the minors, but Adirondack had less than most teams. More than 30 players played 200 or more games, nine played 300 or more, and two—forward Glenn Merkosky and defenseman Greg Joly—dressed for more than 400. That kind of stability helped Adirondack make the Calder Cup playoffs in 19 of their 20 seasons.

Hall of Famer Adam Oates spent time in Adirondack. Neil Smith, who went on to build the team that ended the New York Rangers’ 54-year Stanley Cup drought in 1994, was Adirondack’s GM before being hired by New York in 1989.

By the late 1990s, the Red Wings began looking to bring their AHL team closer to Detroit. The Red Wings shared the Cincinnati Mighty Ducks with Anaheim from 1999 to 2002 before getting their own AHL team in Grand Rapids in 2002. The franchise that was Adirondack went dormant until 2002, when it was purchased by the NBA’s San Antonio Spurs. The San Antonio Rampage will serve as the St. Louis Blues’ AHL team beginning in 2018–19.

27 Jeff Blashill never saw the ice in the NHL after playing three seasons in the USHL and four at Ferris State University. But he wasted little time getting into coaching and was named as the Red Wings’ new bench boss on June 9, 2015, after Mike Babcock left to take over the Toronto Maple Leafs.

Though he was just 41 when he took over the Red Wings, Blashill didn’t lack for experience. One year after finishing his playing career, Blashill returned to his alma mater as an assistant coach. Three seasons later, he moved on to Miami University in Ohio, where he spent six more seasons as an assistant.

Blashill got his first chance to run a team in 2008–09, when he took over the Indiana Ice of the USHL. He led Indiana to a 39–19–2 record in his first season, and the Ice went on to win the league championship. They were 33–24–3 in his second season, but lost in the second round of the playoffs.

The next step was Western Michigan, where he led the Broncos to a 19–13–10 record in 2010–11. That turned out to be his one and only season at WMU. The Red Wings hired him as an assistant under Babcock in July 2011.

Blashill spent one season as an assistant in Detroit before taking over as coach of the Red Wings’ AHL farm team, the Grand Rapids Griffins. He got the job when Curt Fraser left to become an assistant with the Dallas Stars.

As he had done at Indiana, Blashill coached his new team to a title in his first season. The Griffins won the Calder Cup in 2013, the first AHL title in the franchise’s history. The Griffins were 88–48–2–12 in their next two seasons, and Blashill was named the AHL’s outstanding coach in 2014–15. When Babcock left to go to the Maple Leafs, Detroit GM Ken Holland wasted little time promoting Blashill to replace him.

28 Anthony Mantha had everything the Red Wings could have asked for when they selected him in the first round (No. 20) of the 2013 NHL Draft—including good hockey genes.

Mantha, a native of Longueuil, Quebec, scored 50 goals for Val-d’Or of the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League in his draft season, then bumped that total to 57 in 2013–14. But an ankle injury sustained in training camp derailed his hopes of making the Red Wings right away, and he spent all of the 2014–15 season and most of 2015–16 with Detroit’s AHL affiliate, the Grand Rapids Griffins.

Mantha got his first taste of the NHL during a late-season call-up, and he scored his first NHL goal on March 25, 2016, when he followed the rebound of a shot by Brad Richards and shoveled the puck past Canadiens goalie Ben Scrivens for a goal he’ll never forget. His proud grandfather, Andre Pronovost, was on hand at Joe Louis Arena.

Pronovost was a left wing who had helped the Montreal Canadiens win the Stanley Cup four times in a row from 1957 to 1960. He later played three seasons with the Red Wings.

He was caught on camera with a tear in his eye as Mantha’s family celebrated Anthony’s first NHL goal, one that, ironically, came against the Canadiens.

“It’s unbelievable,” Mantha said, after his goal turned out to be the game-winner in a 4–3 victory. “Obviously, my grandparents were very happy, my parents also. My friends were probably jumping. One of my buddies told me he was going to go around the rink screaming if I scored.”

Pronovost was among the people Mantha had phoned 11 days earlier, when he’d found out he was joining the Red Wings.

“I called him the day I got called up but haven’t talked to him since,” Mantha told the Detroit Free Press.

Even better was to score his first NHL goal against the team his grandfather had played for and that Mantha rooted for as a boy.

“That was my club growing up, my hometown, where I grew up,” Mantha said of Montreal, “My grandfather brought me to games there.”

29 Gustav Nyquist’s road to the NHL started in Sweden, where he played for the Malmo Redhawks organization all the way through 2007–08. But it’s here his story takes a twist.

In addition to his hockey skills, Nyquist was also a top student in high school. The Red Wings had drafted him in the fourth round (No. 121) of the 2008 NHL Draft, but Nyquist came to North America and enrolled at the University of Maine.

Nyquist was the top scorer for the Black Bears in each of his three seasons. In 2009–10, he led all of NCAA Division I in scoring with 61 points (19 goals, 42 assists) and was a finalist for the Hobey Baker Award, given to the top player in Division I. After putting up 51 points (18 goals, 33 assists) in 2010–11, he signed a two-year, entry-level contract with the Red Wings.

Nyquist spent most of his first full pro season with Grand Rapids, the Wings’ affiliate in the American Hockey League, before making his NHL debut against the Minnesota Wild on November 1, 2011. He scored his first NHL goal on March 26, 2012, against the Columbus Blue Jackets.

Nyquist spent most of 2012–13 with Grand Rapids, largely because of the lockout that reduced the NHL season to 48 games. He had 60 points (23 goals, 37 assists) for Grand Rapids during the regular season, then contributed seven points (two goals, five assists) to the Griffins’ run to the Calder Cup championship.

It took until the 2013–14 season for Nyquist to earn a full-time job with the Red Wings. After putting up 21 points (seven goals, 14 assists) in 15 games for Grand Rapids, he became a full-time Wing and led Detroit with 28 goals, despite playing just 57 games. On July 10, 2015, he signed a four-year contract with the Wings. A 27-goal, 54-point season followed in 2014–15, before he had 17 in 2015–16, 12 goals (but 36 assists and 48 points) in 2016–17, and 21 goals in 2017–18.

30 Henrik Zetterberg was determined to remain with the Red Wings, the team that had taken him in the seventh round (No. 210) of the 1999 NHL Draft. With the Wings, he’d become an NHL star, winning the Conn Smythe Trophy as playoff MVP when the Red Wings won the Stanley Cup in 2008.

Zetterberg entered the final season of his contract in 2008–09, but midway through the season, the Red Wings acted to make sure he’d be in Detroit throughout his NHL career. On January 28, 2009, the Red Wings announced that Zetterberg had come to terms on a 12-year contract worth $73 million that would keep him in red and white through the 2020–21 season.