1 The National Hockey League was a seven-team, one-division league in 1925–26, with the Ottawa Senators winning the regular-season championship but losing to the Montreal Maroons in the league final. The Maroons went on to defeat the Victoria Cougars of the Western Hockey League to win the Stanley Cup. It was the last time a non-NHL team played for the Cup, as the WHL folded after the season.

Three of the seven teams played in the United States—the Boston Bruins had joined the NHL in 1924, followed by the New York Americans and Pittsburgh Pirates a year later—and now the NHL was looking to expand its footprint in the US.

When league officials met on April 18, 1926, they faced a host of applications. Madison Square Garden, where the Americans rented ice for their home games, wanted a team of its own. Groups from Detroit, Chicago, Cleveland, New Jersey, and Hamilton, Ontario, also were interested in bringing an NHL team to their cities.

The application by Madison Square Garden to ice a team, which became the New York Rangers, was approved quickly. But the NHL decided to do additional due diligence on the other hopefuls. There was opposition among some teams to adding more than one team, while at the time the league constitution said any expansion had to be approved by unanimous vote.

The Americans, in particular, weren’t in favor of a team in Detroit. They preferred to have two teams in Chicago, as eventually would be the case in New York. But on May 2, 1926, the league amended its constitution to make expansion possible by a mere majority vote. After that, it seemed predestined that Chicago and Detroit would join the Rangers as new NHL teams for the 1926–27 season.

On May 15, 1926, a group of investors was tentatively awarded a Detroit franchise, on condition that there would be an arena ready for the 1926–27 season. With the WHL in its death throes, Lester and Frank Patrick sold the Victoria Cougars to the Detroit group for $100,000. The owners kept the nickname “Cougars.” Perhaps oddly, the NHL doesn’t consider the current Red Wings to be a continuation of the Victoria franchise.

However, the arena, which later became known as Olympia Stadium (or merely “The Olympia”), wasn’t ready, forcing the new team to play its first season in Windsor, Ontario. But the franchise was permanently approved on September 25, 1926, the same day as the new Chicago franchise, known as the Black Hawks. (The team changed to the one word “Blackhawks” in 1986.) All three newcomers made their NHL debuts for the 1926–27 season.

2 Chris Chelios began his NHL career with the Montreal Canadiens after playing for the United States at the 1984 Sarajevo Olympics. He was traded to the Chicago Blackhawks in the summer of 1990 and soon seemed like an institution in his hometown. Chelios was one of the NHL’s best defensemen even as he seemed headed toward the end of his career in 1998–99. Indeed, the 37-year-old, a three-time Norris Trophy winner, looked like he might play out the remainder of his NHL career in the city where he’d been born.

Chelios was one of those players opposing fans loved to boo—and Detroit fans were no exception. The idea that he could end up with the Red Wings seemed preposterous.

But the Blackhawks had hit the skids in the late 1990s, missing the playoffs in 1998 and on track to do the same thing in 1999. As the NHL trade deadline approached, the Hawks began to consider moving out some of their older players. Meanwhile, the Red Wings were trying for a three-peat and felt they needed some help on defense.

Chelios had voiced his dislike of the Red Wings on multiple occasions, stating they were overrated and vowing he’d never, ever go to Detroit. To top it off, he had a no-trade clause to back him up.

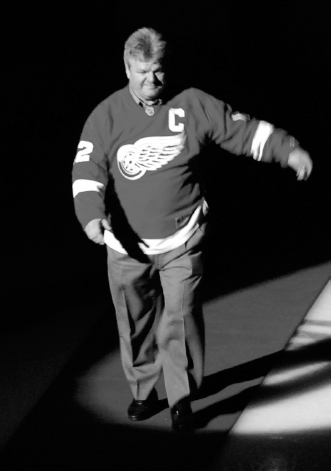

Hall of Fame defenseman Chris Chelios won the Stanley Cup with the Red Wings in 2002 and 2008 after being acquired from the Chicago Blackhawks. (dan4th - 080202 red wings at bruins (120); License: CC BY 2.0 Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4833545)

But whether it was the possibility of winning the Stanley Cup for the second time (he’d played on Montreal’s championship team in 1986), or some other reason known only to him, Chelios opted to waive his no-trade clause when the Red Wings inquired about acquiring him.

On March 23, 1999, the Red Wings got their man. Chelios was traded to the Red Wings for defenseman Anders Eriksson and Detroit’s first-round picks in the 1999 and 2001 NHL drafts.

That might have seemed like a big price for a 37-year-old defenseman. In truth, it turned out to be a bargain. Eriksson, who had been Detroit’s first-round pick (No. 22) in the 1993 NHL Draft, played in the NHL for most of the next decade but never became an impact player. Neither did forward Steve McCarthy and goaltender Adam Munro, the players the Blackhawks selected with the two first-round picks.

In contrast, Chelios proved to be a lot more than a rental. He spent the next decade with the Red Wings, helping Detroit win the Cup in 2002 and 2008. He was named a First-Team All-Star in 2002, at age 40, and ended up playing 578 games with the Wings.

3 With the exception of Wayne Gretzky, who won it nine times, no player has won the Hart Trophy, given by the NHL to “the player adjudged the most valuable to his team,” more than Gordie Howe.

But unlike Gretzky, who won the Hart in each of his first eight NHL seasons, missed in one season, and then won his ninth MVP award, Howe spread his over a span of 12 seasons.

Howe led the NHL in scoring in 1950–51, his fifth NHL season, but ended up in a tie for third with teammate Red Kelly in balloting for the Hart, with Milt Schmidt of the Boston Bruins finishing first and Maurice Richard of the Montreal Canadiens coming in second. In 1951–52, Howe again led the NHL in scoring, again finishing with 86 points in 70 games, and this time was recognized as the league’s MVP. He received nine of the 16 first-place votes and finished well ahead of Montreal center Elmer Lach.

Howe was even better in 1952–53, again leading the NHL in scoring and setting a league record with 95 points, including 49 goals. The Red Wings finished first in the regular-season standings, and Howe cruised to another MVP award, finishing first on nine of the 16 ballots. His 58 points were more than the combined totals of Kelly and Chicago Black Hawks goaltender Al Rollins, who tied for second.

Despite leading the NHL in scoring again in 1953–54, Howe came in fourth in the Hart Trophy race. In 1954–55, he had 62 points in 64 games and didn’t even get a vote for the Hart—the last time that happened until 1970–71, his final season with the Red Wings.

Howe had 79 points, including 38 goals, in 1955–56 and finished seventh in the Hart Trophy balloting. But he took home the Hart for the third time in 1956–57 after leading the NHL in scoring with 89 points, including a league-high 44 goals.

Though Howe didn’t lead the NHL in scoring in 1957–58, he finished with 77 points in 64 games, enough to win the Hart for the fourth time. He finished comfortably ahead of New York Rangers right wing Andy Bathgate.

The voting was flipped in 1958–59, with Bathgate finishing ahead of Howe despite the fact the Rangers collapsed down the stretch and finished out of the Stanley Cup Playoffs. However, Howe made it five MVP awards in 1959–60, even though his scoring totals were comparatively low for him: “just” 28 goals and 73 points.

Howe averaged more than a point a game in 1960–61 and 1961–62 and drew a good measure of support in the Hart balloting each season, but came in third and fourth, respectively.

His sixth and final Hart Trophy came in 1962–63, when he led the NHL in goals (38) and points (86), finishing well ahead of Chicago Black Hawks center Stan Mikita.

Though Howe was a First-Team or Second-Team All-Star in each of the next seven seasons, he never finished better than third in the voting for the Hart Trophy. Not until 1970–71 was he completely omitted from the voting.

Aside from Gretzky and Howe, no player has won the Hart Trophy more than four times. The 12 years between his first and last MVP awards represent the longest gap in NHL history.

4 The 1949–50 Red Wings were a powerhouse. They lapped the field during the regular season, winning the Prince of Wales Trophy as the NHL’s top finisher with a record of 37–19–14. Their 88 points were 11 more than the second-place Montreal Canadiens.

The Red Wings led the NHL in goals scored with 229. The last-place Chicago Black Hawks were next at 203. The Wings’ 164 goals allowed were the second-fewest behind the 150 surrendered by Montreal.

Detroit’s famed “Production Line” dominated the scoring race. Left wing Ted Lindsay won the Art Ross Trophy as the NHL’s leading scorer with 78 points, followed by center Sid Abel with 69 and Gordie Howe with 68. Goalie Harry Lumley was tops in the NHL with 33 wins and second to Montreal’s Bill Durnan with a 2.35 goals-against average.

The Wings were a huge favorite to capture the Stanley Cup when they opened their Semifinal series against the third-place Toronto Maple Leafs, the three-time defending NHL champions, at the Olympia, on March 28. But they suffered a huge loss in that game when Howe went down with a head injury that ended his season—and nearly his life.

The Leafs jumped out to a 3–0 lead in Game 1. In the second period, Howe, three days shy of his 22nd birthday, came charging towards Ted “Teeder” Kennedy as the Toronto captain spearheaded a rush through center ice. But Kennedy saw out of the corner of his eye that he was about to be hammered into the boards, so he abruptly pulled up.

Howe stumbled, glanced off his intended target, and went headfirst into the top of the boards in front of the Detroit bench. Teammate “Black Jack” Stewart couldn’t stop his momentum and fell over Howe.

The result was catastrophic. Stewart got up but Howe stayed on the ice, unmoving. He was bleeding and unconscious. As the packed house watched in stunned silence, Howe was stretchered off the ice, taken into the dressing room for assessment and then rushed by ambulance to Harper Hospital.

Howe had broken his nose, shattered his cheekbone, and seriously scratched his right eye. More important, it seemed probable he’d fractured his skull.

His brain hemorrhaged. Shortly after midnight, a neurosurgeon began a delicate, life-saving operation. An opening was drilled into Howe’s skull, from which the surgeon drained fluid to relieve pressure on the brain. After the 90-minute operation, Howe was put in an oxygen tent.

Happily, the operation was a success, and Howe wound up pulling through. Fourth-graders at a local Catholic school felt they’d had a hand in his recovery. Their teacher was Lindsay’s sister, and she had asked them to pray for a special friend of hers.

Although Kennedy was widely vilified, an inquiry by the NHL cleared him of any blame in the accident. Kennedy always maintained that the only thing he was guilty of was getting out of the way. Though many of the Wings agreed with that view in private, the team’s public stance was outrage; the organization contended that Kennedy had butt-ended Howe in the eye, causing him to crash into the boards.

The Red Wings lost, 5–0, in Game 1 and trailed the series, 3–2, before Lumley blanked the Leafs in Game 6. Lumley and Toronto’s Turk Broda matched saves through three periods in Game 7 before Leo Reise, whose goal 38 seconds into double overtime had won Game 4, scored 8:39 into OT for a 1–0 victory that eliminated the Leafs and sent the Wings into the Final against the New York Rangers.

The Howe-less Red Wings got all they could handle from the Rangers before winning Game 7 in double overtime for their first of four championships in a span of six seasons.

5 By the mid-1990s, the Red Wings had established themselves as one of the NHL’s elite teams. They’d won their division in 1993–94 (though they were upset by the San Jose Sharks in the first round of the Stanley Cup Playoffs), got to the Final in 1995 (but were swept by the New Jersey Devils), and set an NHL regular-season record for wins in 1995–96, before being eliminated by the Colorado Avalanche in six games in the Western Conference Final.

Game 6 of that series lit the fuse on one of the most intense rivalries during the next few seasons.

Just over 14 minutes into the game, Colorado’s Claude Lemieux checked Detroit center Kris Draper from behind, sending him face-first into the boards. The hit sent Draper to the hospital with a broken jaw, as well as shattered cheek and orbital bones. He required reconstructive surgery that necessitated having his jaw wired shut, and there were numerous stitches.

Lemieux received a major penalty for checking from behind and a game misconduct. Detroit’s Paul Coffey scored during the ensuing five-minute power play to tie the game, 1–1, but Colorado scored three times in the second period for a series-clinching 4–1 victory and went on to sweep the Florida Panthers to win the Stanley Cup in their first season in Denver after the franchise moved from Quebec.

The teams held the traditional handshake after the Avalanche eliminated the Red Wings, although forward Dino Ciccarelli said of his encounter with Lemieux, “I can’t believe I shook this guy’s friggin’ hand after the game. That pisses me right off.”

The teams played three times during the 1996–97 season without a major incident. Colorado won all three games, giving the Avs seven wins in nine tries against the Wings. But the fourth game, on March 26, 1997, at Joe Louis Arena, was the Red Wings’ night for revenge.

Two defensemen, Colorado’s Brent Severyn and Detroit’s Jamie Pushor, fought 4:46 into the game. Next, forwards Kirk Maltby of the Wings and Rene Corbet of the Avs squared off at 10:14. But with Colorado leading, 1–0, late in the first period, the real fireworks broke out at 18:22.

After a collision between Detroit center Igor Larionov and Colorado’s Peter Forsberg, Detroit’s Darren McCarty took the opportunity to avenge Lemieux’s attack on Draper. He escaped the linesman who was trying to control him and blindsided Lemieux with a right hook. Lemieux turtled as McCarty rained punches on him, and then McCarty dragged Lemieux to the boards and kneed him in the head before officials were able to get him away.

Avs goaltender Patrick Roy wanted to get in on the action, but he was clotheslined by Detroit’s Brendan Shanahan. After Detroit goalie Mike Vernon tried to pull Colorado defenseman Adam Foote off Shanahan, Roy pulled him away, the two goaltenders dropped their masks and gloves, then staged one of the more memorable goalie fights in NHL history.

The outcome left the Wings down a man; McCarty’s double minor for roughing was the only unmatched penalty. Just 15 seconds later, Detroit’s Vladimir Konstantinov and Colorado forward Adam Deadmarsh went at it.

There were five more fights in the second period, which ended with Colorado ahead, 4–3. Valeri Kamensky’s goal early in the third period put Colorado ahead, 5–3, but the Red Wings tied it on goals by Martin Lapointe and Shanahan, then won it when McCarty scored 39 seconds into overtime.

The teams went at it again on May 22, during Game 4 of the Western Conference Final. Though the outcome was long settled (the Wings won, 6–0), the teams had four fights in the third period. Colorado coach Marc Crawford screamed obscenities at his Detroit counterpart, Scotty Bowman, across the glass between the benches. The tirade earned him a $10,000 fine from the NHL.

The Red Wings went on to eliminate the Avs and win the Cup, but the fireworks weren’t over.

On November 11, 1997, McCarty and Lemieux began exchanging punches three seconds after the opening faceoff at Joe Louis Arena, delighting the sellout crowd that saw Lemieux as Public Enemy No. 1.

The Avs came back to Detroit for a game on April 1, 1998, that featured 228 penalty minutes and another battle between the goaltenders. With 7:11 remaining, Roy challenged Detroit’s Chris Osgood. The two fought at center ice, earning fighting penalties and game misconducts and forcing each team to use its backup goaltender to finish the game, a 2–0 win for the Avalanche.

Roster turnover on both sides began to water down the rivalry. The last big scrap between the teams took place in the third period at Pepsi Center in Denver on March 23, 2002. Shortly after the Wings had taken a 1–0 lead, Maltby crashed the net and Roy took exception. Detroit goaltender Dominik Hasek skated the length of the ice, and only the intervention of the officials kept Roy from fighting his third different Detroit goaltender in five years.

The Red Wings got the ultimate revenge in Game 7 of the 2002 Western Conference Final. With the packed house at Joe Louis Arena bellowing its approval, the Wings stomped the Avs, 7–0. Six of the goals came against Roy, who was lifted after two periods. The Red Wings went on to their third championship in six seasons.

6 Red Kelly had a career almost unparalleled in hockey. He was an elite defenseman for more than a decade with the Red Wings, then went on to a second life as one of the NHL’s best two-way centers with the Toronto Maple Leafs.

Kelly is often forgotten today, a relic from an era in which few NHL games were on television and the league was a collection of six teams that went no further west than Chicago. He didn’t have the kind of flashy style that drew a lot of attention; rather, he was the kind of player you had to watch night in and night out to really appreciate.

The guys he played with and against had no such problem recognizing his abilities.

“Red was the best,” Gordie Howe said when he was interviewed by Rich Kincaide for his book The Gods of Olympia Stadium. “He was very much a mobile defenseman like Doug Harvey. Red was a better skater. And he was strong.”

It’s hard to believe now, but Kelly’s skating originally kept him from making the junior clubs at St. Michael’s in Toronto. But his hockey IQ was so apparent that the coaching staff reconsidered, and his work ethic helped him improve his game. With some help from one of his heroes, former Maple Leafs star Joe Primeau, he became a star in junior hockey and attracted the attention of the Red Wings. After St. Michael’s won the Memorial Cup in 1947, Kelly went straight to Detroit, never spending a day in the minor leagues.

Among the lessons Kelly learned from Primeau was to control his temper—after all, no one has ever scored a goal from the penalty box. Kelly played hard but clean. In nearly 13 full seasons with the Red Wings, he never had more than 39 penalty minutes in a season and won the Lady Byng Trophy for skillful and gentlemanly play three times, the last in 1953–54. No defenseman won the award again until Brian Campbell of the Florida Panthers did it in 2011–12.

Kelly did more than keep the puck out of Detroit’s net. In an era when defenseman weren’t big offensive contributors, he had at least 15 goals and 40 points per season from 1949–50 through 1955–56. He won the Norris Trophy as the NHL’s top defenseman in 1954 and was a First-Team or Second-Team NHL All-Star from 1949–50 through 1956–57.

Kelly was so exceptional defensively that his coaches took advantage of his superb conditioning by giving him all the ice time he could handle. He recalled in Legends of Hockey that coach Tommy Ivan “used me as much as 55 minutes in a game in Detroit. I was always in great shape; I guess that helped keep me in great shape, and whenever you want me to go, I went.”

Red Kelly played on four Stanley Cup-winning teams with the Red Wings as a defenseman and four more with the Toronto Maple Leafs as a center. (Associated Press)

Kelly was a key to one of hockey’s great teams. The Red Wings finished first for an NHL-record eight straight seasons and won the Stanley Cup in 1950, 1952, 1954, and 1955.

In the end, Kelly’s eagerness to help the team turned out to be the reason for his departure from Detroit. When management asked him to play shortly after he broke an ankle in the latter stages of the 1958–59 season, Kelly had the ankle taped and returned to the lineup, missing only a handful of games. But his play was below his usual standard, and Detroit missed the playoffs for the first time in 21 seasons. Because news of the injury had been kept secret, there were rumors that Kelly was washed up, but after he healed and rebounded the following autumn, he told a reporter about the injury. General manager Jack Adams was furious and traded Kelly to the New York Rangers.

Kelly refused to go, insisting he’d had enough and was going to retire. The trade was nullified, and Kelly quickly got a job with a tool company in Detroit. But just a few days later, Maple Leafs coach and GM Punch Imlach was able to talk him out of retirement. The Leafs and Wings worked out a deal for Kelly’s rights—at 32 years old, Kelly was living his childhood dream of skating for the Maple Leafs.

Imlach converted Kelly into a center with the idea that he’d be perfect for shutting down stars like Montreal’s Jean Beliveau. The strategy worked so well that the Maple Leafs won four Cups in six seasons—1962, 1963, 1964, and 1967. Kelly retired after the fourth Cup, his eighth … and Toronto hasn’t won one since.

7 There’s a price for everything. For the Red Wings, the price they paid for making the Stanley Cup Playoffs for 25 consecutive seasons was not picking high in the NHL draft. Unlike the 1980s, when the Red Wings usually picked very high—Steve Yzerman was the fourth player taken in 1983—beginning in 1992, they had no pick in the top 10 until 2017.

Before they took Michael Rasmussen with the No. 9 choice in ’17, the last player taken by the Wings with a top-10 pick was Martin Lapointe, who was selected as No. 10 in 1991.

Lapointe, a center, was coming off seasons of 42 and 44 goals with the Laval Titans of the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League when he was taken by the Red Wings in 1991. By the end of the 1991–92 season, he was already playing in the NHL.

Lapointe played four regular-season games and three Stanley Cup Playoff games. He scored 25 goals in 28 games with the Adirondack Red Wings of the American Hockey League in 1993–94 and had eight goals and 16 points in 50 games with Detroit. After spending the first part of the 1994–95 season with Adirondack while the NHL was idled because of the owners’ lockout, Lapointe joined the Red Wings after play resumed and never looked back.

Though Lapointe had been a big scorer in junior hockey, his role in the NHL was more of a checking center—and, to be fair, on a team that had Steve Yzerman and Sergei Fedorov, there aren’t many players who’d have been a first- or second-line center ahead of those two.

But Lapointe had his uses. He had 63 goals and 137 points in a span of four seasons from 1996–97 through 1999–2000 and played on Detroit’s Stanley Cup-winning teams in 1997 and 1998.

Lapointe had a breakout season offensively in 2000–01, scoring 27 goals and finishing with 57 points. His timing was perfect. The big numbers came just before he was due to become a free agent and earned him a four-year, $20 million contract with the Boston Bruins. Unfortunately for his new employers, Lapointe reverted to form as a checking center who was a useful, but not prolific offensive contributor. He never had more than 15 goals or 40 points in a season again before retiring in 2008.

8 The 1989 NHL Draft marked a turning point for the Red Wings. Few teams have helped themselves more in the span of a few hours than the Wings did on June 17, 1989, at Met Center in Bloomington, Minnesota. After all, how many teams select four 1,000-game players on the same day?

“I don’t think there was a better draft in the history of hockey than our draft, the Red Wings’ draft, in ’89,” general manager Jim Devellano told NHL.com in 2015. “I’m also here to tell you there was some luck involved.”

Truer words were never spoken. The Red Wings selected two future Hockey Hall of Famers in 1989, although neither went in the first round. Instead, the Wings chose center Mike Sillinger from the Regina Pats of the Western Hockey League with the 11th pick in the opening round.

Sillinger was coming off a 53-goal, 131-point season with Regina when the Red Wings selected him. He returned to the Pats for two seasons, scoring 57 and 50 goals in his age-19 and -20 seasons. But he never came close to those numbers in an NHL career that saw him play with a league-record 12 teams.

His best offensive season came as a 35 year old, when he scored 26 goals and finished with 59 points for the New York Islanders in 2006–07. He retired from the NHL two years later with 240 goals and 548 points in 1,049 games, though just 128 with the Wings.

Rugged defenseman Bob Boughner went to the Wings in the second round. He ended up playing 630 NHL games with six teams, none of them with the Red Wings, who traded him to the Buffalo Sabres while he was still in the minor leagues.

The idea that Boughner was picked ahead of Nicklas Lidstrom seems almost laughable now; Lidstrom went on to become one of the top half-dozen defensemen in NHL history and was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2015, his first year of eligibility.

But scouting in 1989 wasn’t nearly as thorough as it is today. The Red Wings were one of the few teams that had scouted Lidstrom extensively and did their best to keep word of their interest in him from leaking out. They were able to nab him in the third round (No. 53). Lidstrom stayed in Sweden for two more seasons before coming to the Wings in 1991. He never left, finishing his Hall of Fame career with 264 goals and 1,142 points in 1,564 games, all with the Wings.

Finding a player like Lidstrom in any round of a draft would be enough for most teams. But Detroit made it back-to-back future Hall of Famers when Russian center Sergei Fedorov was taken in the fourth round (No. 74).

Fedorov wasn’t exactly a secret. He had centered a line with Alexander Mogilny and Pavel Bure that had helped the Soviet Union win the World Junior Championship and was regarded as one of the best young talents in hockey. He lasted as long as he did because there was no certainty he’d ever be able to play in North America.

Earlier in 1989, Mogilny had become the first defector from the USSR to play in the NHL when he joined the Buffalo Sabres. Jim Lites, then an executive vice president and chief operating officer of the Red Wings, met with Fedorov a few months later and offered to help him defect. But Fedorov said he wanted to finish his season with the Soviet Red Army team and complete his military service so as not to be branded a traitor before making any move.

The Goodwill Games, a creation of media mogul Ted Turner, were held in the USSR in 1986 and were scheduled for 1990 in Seattle. Though the Games were to be held in the summer, there was to be a hockey competition. After an exhibition game in Portland, Oregon, Fedorov defected and was flown to Detroit. He spent his first 13 NHL seasons with the Red Wings and played in three Stanley Cup champions in Detroit. Fedorov played 1,248 games, finishing with 483 goals and 1,179 points before returning to Russia for three more seasons.

But Devellano wasn’t finished with this draft. In the sixth round, the Wings took center Dallas Drake, who ended up playing 1,009 games and scoring 177 goals. He spent his first two seasons with Detroit, then returned to the Wings in 2007–08 and retired after the Wings won the Stanley Cup.

But for a tragic accident, there could have been five 1,000-game players in the 1989 draft. Defenseman Vladimir Konstantinov, Detroit’s 11th-round pick (No. 221), played in 446 games in a career that was cut short by a limo accident he was involved in the day after the Red Wings won the Stanley Cup in 1997.

“It can’t happen again, because guys like Lidstrom and Fedorov, now they go in the top five,” Ken Holland, who went on to become Detroit’s GM, told NHL.com. “It’s a different time. You can’t have those kinds of drafts. You can still get three, four, or five players out of a draft, but you’re not going to get two Hall of Famers and a bunch of people who will play in 1,000 games.”

9 The Red Wings were favored to defeat the New Jersey Devils when the teams faced off in the 1995 Stanley Cup Final. The Devils had finished fifth in the Eastern Conference during the lockout-shortened 1994–95 season with a 22–18–8 record, while the Red Wings won the Presidents’ Trophy by going 33–11–4.

But the Devils caught fire during the Stanley Cup Playoffs, capping the franchise’s first championship by sweeping the Red Wings in the Final. One reason for the Devils’ success was their “Crash Line” of Bobby Holik between Mike Peluso and Randy McKay. All three were 200-plus pounds and played a physical brand of hockey that made life miserable for opponents. They could also put the puck in the net, but their main function was to crash and bang.

It’s said that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and the Wings decided they needed their own version of the “Crash Line.” Coach Scotty Bowman found what he was looking for when he put center Kris Draper together with wingers Kirk Maltby and Joe Kocur. Draper provided speed and the ability to win faceoffs, Maltby was an excellent checker, and Kocur was one of the NHL’s true heavyweights.

When the Red Wings made it back to the Final, in 1997, against the Philadelphia Flyers, the “Grind Line” spurred the Wings to a sweep for their first Cup since 1955. The trio stayed together to help the Wings win again in 1998.

Darren McCarty took Kocur’s spot on the line after the 1997–98 season (Kocur retired in 1999), and the trio stayed together through the 2003–04 season. When play resumed after the 2004–05 lockout, the Red Wings bought out McCarty, who spent the next two seasons with the Calgary Flames before returning to the Wings in 2007–08 and reuniting with his old linemates in time to help Detroit win the Cup again.

Darren McCarty was part of the “Grind Line” that did a lot of the dirty work on Detroit’s Cup-winning teams. (Associated Press)

10 For decades, NHL teams liked to stay in-house when selecting a new coach or general manager. The Red Wings were no different. Several of their biggest stars spent time behind the bench or in the front office after their playing days were done.

Ted Lindsay was a star with the Wings in the 1940s and 1950s. After retiring, he became a broadcaster for several years before rejoining the Red Wings in 1977 as their general manager. The Red Wings returned to the Stanley Cup Playoffs in 1978, and Lindsay was voted the NHL’s executive of the year. He named himself coach late in the 1979–80 season but was fired after Detroit went 3–14–3 to start the 1980–81 season.

Bill Gadsby was a defenseman who spent the last five seasons (1961 to 1966) of his Hall of Fame career with the Red Wings. Two seasons after leaving the Red Wings as a player, he returned as their coach. Detroit went 33–31–12 under Gadsby in 1968–69 but missed the Stanley Cup Playoffs. They won their first two games of the 1969–70 season under Gadsby, earning congratulations from owner Bruce Norris.

“We were 8–1 in the exhibition games and won the first two in the regular season,” Gadsby told the Toronto Star in 2000. “Bruce Norris came into the dressing room, put his arm around me, and told me I was doing a hell of a job. Next day he fired me. I never have figured out why.”

Alex Delvecchio retired as a player early in the 1973–74 season and immediately went behind the bench. The Red Wings finished 27–31–9 and missed the playoffs. He coached the Red Wings and even added the general manager’s job to his portfolio at one point, before leaving in 1977 and becoming a successful businessman.

Though Gordie Howe spent 25 seasons with the Red Wings as a player, he never officially served as coach. Howe retired as a player in 1971, then spent the next two seasons in Detroit’s front office before returning to the ice as a player with the Houston Aeros of the World Hockey Association. He returned to the NHL in 1979 with the Hartford Whalers and played one more season before calling it quits for good. He never did officially coach the Red Wings.

11 There’s no evidence that Alex Delvecchio was ever overweight, but the Hall of Fame center carried the nickname “Fats” for most of his NHL career because his face had some baby fat when he first entered the NHL. In fact, he looked like an 18 year old well after he had become one of the NHL’s top players and a future Hall of Famer.

He retired on November 7, 1973, having played 1,549 regular-season games and finishing with 456 goals and 825 assists for 1,281 points. At the time he called it a career, he ranked second to longtime linemate Gordie Howe in all three categories. He also had 35 goals and 104 points in 121 Stanley Cup Playoff games.

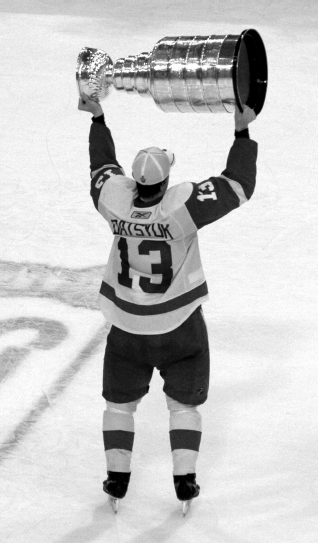

Pavel Datsyuk could do things with the puck most players could only dream of. The “Datsyukian Deke” on breakaways and, especially, shootout attempts became a fixture in the lexicon of Detroit hockey fans. He was a maestro with the puck, a true magician when it came to finding ways to take it away from opponents and keep it away while generating offense.

Datsyuk earned the nickname “Magic Man” after his dazzling performances became the norm. Datsyuk’s goals, stickhandles, and passes became consistent highlight-reel material, and his moves routinely hit six figures in views on YouTube. As a true wizard with the puck, the nickname was a perfect fit. Type “Magic Man” into a search engine and you’ll see for yourself.

Johan Franzen’s nickname came from Steve Yzerman, who dubbed him “Mule” during his rookie season in 2005–06 after the 6-foot-3, 220-pound forward whizzed past him on the ice. Yzerman said he earned it because “he carried the load.”

“He’s big and strong, and he reminded me of a mule that day,” Yzerman told the Canadian Press in 2008. “His offensive game really started to show up last year, and now that his confidence has grown, he is holding onto the puck and making plays.”

But it took a little while for Franzen to feel comfortable with the nickname.

“At first, he didn’t know what [mule] meant and didn’t know if it was a good or a bad thing,” defenseman Niklas Kronwall, Franzen’s road roomie, said in 2008. “Once he found out what it meant, he was proud of it.”

Franzen may have taken a while to realize that “Mule” was actually a compliment, but there was no doubt about Nicklas Lidstrom’s nickname being favorable—after all, how many of us wouldn’t want to be called “The Perfect Human.”

On the ice, Lidstrom was about as close to perfection as a player could be. He won the Norris Trophy seven times—more than anyone except Bobby Orr—was part of four Stanley Cup-winning teams with the Red Wings, won the Conn Smythe Trophy in 2002, and was the team captain for his last six seasons.

Johan Franzen was dubbed “Mule” by Steve Yzerman because “he carried the load.” (Michael Miller—Own work; License: CC BY-SA 3.0; Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18308610)

The hardest thing to find was Lidstrom making a mistake, on or off the ice.

“It was Kris Draper and Chris Osgood kind of joking about it, that’s how it first came out, and that’s how it grew,” Lidstrom told MLive.com in 2015, prior to being inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame. “I took a lot of pride in being prepared for games and practices and tried to play at a high level all the time. But that nickname is something I just chuckle about.”

He admitted that the one person who could have crushed that perception was his wife.

“She could have killed that story real quick,” he said.

If hockey were an academic subject, you’d want Igor Larionov as your teacher.

Larionov centered one of the great lines in hockey history, the “KLM Line” with Vladimir Krutov and Sergei Makarov, while playing in the Soviet Union. That’s where he picked up the nickname “The Professor” a tribute to his incredible vision and ability to read the game, as well as his ultra-intelligent appearance off the ice.

Larionov was 28 when he was allowed to come to North America and join the Vancouver Canucks. When he joined the Red Wings, he was close to 35.

“They called him ‘The Professor,’ because of his trademark glasses and [because] he was so smart and even-keeled on the ice and off it,” former Red Wings defenseman Aaron Ward related to the team’s website in 2008. “He played the game with ease and was just always under control. I remember when I’d lose my composure as a young man, he would always tell me, ‘Just think the game. Make decisions as carefully as you can and think about how to approach your next move.’

“I mean, here’s a guy who was maybe 175 pounds and maybe 5-foot-10, but he was so successful on both the international stage and then in the NHL because he always tried to learn the game and then preach what he learned to the young guys around him. He was, and is, one of the best character guys and smartest people I’ve met.”

12 Playoff games that go multiple overtimes are nothing new. But Game 1 of the Semifinals between the Red Wings and the Montreal Maroons on March 24, 1936, still takes the cake. More than eight decades later, it remains unchallenged as the longest game in NHL history.

The teams entered the series evenly matched. The Red Wings (24–16–8) had won the American Division. The Maroons (22–16–10) had finished first in the Canadian Division. Under the playoff format in use at the time, the division winners got a bye through the Quarterfinals but were matched against each other in the Semifinals; the other series matched the two winners from the Quarterfinals, with the winners advancing to the Stanley Cup Final.

Though each team had plenty of scorers, it wasn’t a big surprise that no one was able to get a shot past Detroit goaltender Normie Smith or his Montreal counterpart, Lorne Chabot, through the regulation 60 minutes in the series opener at the Montreal Forum. The zeroes stayed on the scoreboard through the first, second, and third overtimes, with the clock ticking past midnight.

The Zamboni was still more than a decade away from being invented, so the ice deteriorated. By the time the puck dropped for the fourth overtime, the surface was rutted and chewed up, further slowing the game and taking a toll on the skilled players.

Detroit nearly won the game in the fifth overtime when Herbie Lewis went in on a breakaway and beat Chabot. But instead of celebrating a victory, Lewis had to watch the puck clang off the post and away from the net.

Soon after, Montreal had a great chance when Baldy Northcott was set up by Hooley Smith. But to the despair of the crowd, Smith got his pad out and kept the game scoreless.

It was after 2 a.m. when the teams took the ice for the sixth overtime, their ninth period of hockey that night. They had already surpassed the NHL record for the longest game, set by the Toronto Maple Leafs and Boston Bruins on April 4, 1932.

With each coach searching for younger legs, Detroit’s Jack Adams sent out rookie forward Mud Bruneteau on a line with vets Syd Howe and Hec Kilrea. Bruneteau had seen little action after scoring just twice during the regular season. But after sitting for most of the first eight-plus periods, Bruneteau was one of the few players who still had something in the tank.

The sixth overtime had passed the 16-minute mark when Bruneteau controlled the puck in his own zone and passed it to Kilrea to start a rush. Kilrea faked a pass and slid the puck over the blue line, where Bruneteau, the fastest guy on the chewed-up ice, got past the Montreal defense and picked it up.

He went in one-on-one with Chabot and let fly.

“Thank God,” Bruneteau later recalled. “Chabot fell down as I shot the puck into the net. It was the funniest thing: the puck just stuck there in the twine and didn’t fall on the ice.”

Though the goal judge failed to turn on the red light, referee Bill Stewart signaled it was a goal, and after 116 minutes and 30 seconds of overtime, at 2:25 in the morning, Detroit had a 1–0 victory. Though shots on goal were still two decades away from being an official NHL statistic, Smith reportedly finished with at least 90 saves.

According to hockey historian Stan Fischler, there’s one more piece to the story. Bruneteau was back at his hotel room, preparing to undress, when he heard a knock at the door. When he finally answered, there was Chabot.

“Sorry to bother you, kid,” the goaltender said, “but you forgot something when you left the rink.” Then, handing Bruneteau a puck, said, “Maybe you’d like to have this souvenir of the goal you scored.”

The Red Wings went on to sweep the best-of-five series and do the same to the Toronto Maple Leafs in the Final to win the Stanley Cup for the first time in their history,

13 Gordie Howe and Terry Sawchuk might well have won the Conn Smythe Trophy during the Red Wings’ run of four championships in six seasons from 1950 to 1955, but the award for playoff MVP hadn’t been established yet.

It wasn’t until 1965 that the NHL instituted the Conn Smythe, with future Hockey Hall of Famer Jean Beliveau winning the first one after the Montreal Canadiens won their first Cup in five years.

The Canadiens were back in the Final in 1966, this time against the Red Wings. Detroit had finished fourth during the regular season, earning them a meeting with the second-place Chicago Black Hawks.

Chicago had gone 11–1–2 against the Red Wings during the regular season. But behind the play of goaltender Roger Crozier, who allowed 10 goals in the six games, Detroit advanced to the Final against the Canadiens; the regular-season champions had swept the third-place Toronto Maple Leafs in four games.

The Stanley Cup Final opened on April 24, and Crozier continued his superb play by making 33 saves in a 3–2 win at the Forum. Two nights later, Crozier allowed an early power-play goal by J.C. Tremblay, then surrendered just one other goal in a 5–2 win that put the Red Wings in the driver’s seat: They led the series, 2–0, and were coming home for Games 3 and 4.

The Red Wings took an early lead in Game 3 when Norm Ullman scored 4:20 into the game, but Montreal scored four unanswered goals and won, 4–2. Game 4 was scoreless early in the first period when Crozier had to leave with a sprained knee and twisted ankle.

“At first, I thought my leg was broken,” Crozier said of the play. “I was stretching for the corner of the goal when [Montreal forward Bobby] Rousseau fell going through the crease, jamming my leg against the post. There was a searing pain, and my leg went limp. It started to quiver. I couldn’t control it and couldn’t regain my feet.”

Ullman scored midway through the second period to put Detroit ahead, 1–0, but Beliveau tied the score, 1–1, late in the period against Hank Bassen, and Ralph Backstrom’s third-period goal gave Montreal a 2–1 win.

Crozier was back in goal for Game 5, a 5–1 win by the Canadiens at the Forum. The Red Wings rallied from a two-goal deficit to force overtime in Game 6, but Henri Richard scored a disputed goal 2:20 into OT for a 3–2 win that gave the Canadiens the Cup.

Though his team didn’t win the Cup that year, Crozier was selected as the playoff MVP. He learned he’d won the award while he was peeling his uniform away from the injured parts of his body in the Wings’ dressing room. He changed into his street clothes to accept the trophy from NHL President Clarence Campbell. His body may have still hurt, but Crozier’s wallet felt better after he pocketed the $1,000 cash award that came with the Cup, not to mention a sports car.

14 Six players have accounted for the 11 seasons in which a Red Wing has scored 50 or more goals.

By far, the most prolific was Steve Yzerman. He has the three highest-scoring seasons in franchise history: 65 goals in 1999–89, 62 in 1989–90, and 58 in 1992–93. Yzerman also scored 51 goals in 1990–91 and 50 in 1987–88.

Sergei Fedorov (56 in 1993–94), John Ogrodnick (55 in 1984–85), Ray Sheppard (52 in 1993–94), and Danny Grant (50 in 1974–75) had one apiece. Gordie Howe had 49 in a 70-game season (1952–53) and Frank Mahovlich scored 49 in 1968–69, when the season was 76 games.

But the only Red Wing other than Yzerman to score 50 or more goals more than once is probably better known to most of today’s Detroit fans for his work on television rather than his play on the ice.

Mickey Redmond was part of the package the Wings received when they traded Mahovlich to the Montreal Canadiens during the 1970–71 season. Redmond was a two-time Stanley Cup winner and had scored 27 goals in 1969–70, but on a team swimming in talented young forwards, Redmond was regarded as expendable.

Mahovlich helped the Canadiens win the Cup in 1971 and 1973, but the Red Wings had to be more than happy with the return. (They got two useful forwards, Bill Collins and Guy Charron, along with Redmond.)

Given a bigger role, Redmond produced 42 goals and 71 points in 1971–72. But that was just a warm-up for the 1972–73 season, in which he set a Red Wings record by scoring 52 goals. He also had 41 assists to finish with 93 points. Then he proved that was no fluke by scoring 51 in 1973–74. That made him just the third player in NHL history, after Bobby Hull and Phil Esposito, to have back-to-back seasons with at least 50 goals.

Redmond was a First-Team NHL All-Star in 1972–73 and a Second-Team All-Star in 1973–74; at age 27, he appeared ready to remain among the NHL’s top goal-scorers for several more years. But his time as one of hockey’s most feared scorers came to a sudden end early in the 1974–75 season, when a ruptured disc caused permanent damage to a nerve running directly to his right leg.

An operation to repair the problem proved unsuccessful, and Redmond, who would play only parts of his two last seasons in Detroit, called it a career in 1976 at the age of 28.

Today, instead of having become a Red Wings legend as a player, he’s become one as a broadcaster, with generations of fans who never saw his years as a 50-goal scorer coming to know him as one of the voices of winter. He never made the playoffs with the Wings as a player, but he was there to describe the exploits of Detroit’s four Cup-winning teams from 1997 to 2008.

15 Even in the high-scoring 1980s and early 1990s, 70 assists were a lot. Steve Yzerman set the franchise record when he became the second player in Wings history to exceed that mark, in 1988–89, when he piled up 90, a total no one wearing the winged wheel has come close to. The second-highest total in team history also belongs to Yzerman, who set up 79 goals in 1992–93.

Still, the first Red Wing to break the 70-assist mark did so long before Yzerman put on a Detroit sweater.

The Red Wings selected Marcel Dionne with the No. 2 pick in the 1971 NHL Draft. Though he was generously listed at 5-foot-9 (but was likely shorter), Dionne was a solid 180-pound forward who had put up huge numbers with the St. Catharines Black Hawks of the Ontario Hockey League.

Dionne was a sensation as an NHL rookie, scoring 28 goals and finishing with 77 points, though he ended up just third in the balloting for the Calder Trophy as the NHL’s top rookie. He bumped those totals to 40 goals and 90 points in 1972–73 and had 24 goals and 78 points in 1973–74.

By then, the old guard, players such as Gordie Howe and Alex Delvecchio, were gone and Dionne was the team’s unquestioned star.

Early in 1974–75, Delvecchio, now the Wings’ coach, moved struggling forward Danny Grant onto Dionne’s line—and Grant suddenly became a 50-goal scorer. Dionne scored 47 goals—including an NHL-record 10 while Detroit was short-handed—and set franchise records with 74 assists and 121 points. He was awarded the Lady Byng Trophy for gentlemanly and skillful play.

Marcel Dionne set a Red Wings record with 121 points in 1974–75. (Sean Hagen, Maple Ridge, Canada - DSC_0295; License: CC BY-SA 2.0; Credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5260743)

But Dionne’s biggest season with the Red Wings was also his last. When his contract ran out, negotiations on a new deal stalled. The Wings advised his agent to shop Dionne around the NHL, and he landed the richest contract in league history: five years at $300,000 annually from the Los Angeles Kings. The teams worked out a compensation agreement, and Dionne was off to LA, where he proved that his last season with the Wings was no fluke.

16 The Red Wings had no trouble scoring during the 1980s, but a leaky defense and inconsistent goaltending kept Detroit from moving into the NHL’s elite. After the Wings failed to qualify for the Stanley Cup Playoffs in 1990 following back-to-back first-place finishes in the Norris Division, ownership decided to make a change behind the bench.

Out went Jacques Demers, who had gotten the Wings to the conference final in 1987 and 1988. In his place, the Red Wings hired Bryan Murray, who had coached the Washington Capitals to respectability in the 1980s but had been fired during the 1989–90 season.

The Red Wings hired Murray as coach and general manager, with Jim Devellano bumped up to vice president. The Wings made it back to the playoffs in 1990–91 despite finishing under .500 (34–38–8) but were eliminated in the first round.

The defensive structure Murray brought with him began to yield results as the talent base improved. The 1991–92 team jumped from 76 points to 98 (43–25–12) and finished first in the Norris Division, but they were upset in the second round of the playoffs.

The Wings improved again in 1992–93, finishing with 103 points (47–24–9), although they came in second in the Norris.

All that meant nothing in the playoffs, and the Wings failed to get out of the first round. Detroit won the first two games of its series against the fourth-place Toronto Maple Leafs, but Toronto won the next three. The Wings rolled to a 7–3 win in Game 6 at Maple Leaf Gardens, but with a chance to win Game 7 on home ice, the Red Wings couldn’t hold a 3–2 lead in the final three minutes of the third period. Toronto’s Nikolai Borschevsky scored the series-winner at 2:35 of OT to end the Red Wings’ season.

That was the end of Murray’s tenure behind the bench. The Red Wings hired Scotty Bowman as coach, with Murray remaining as GM. After another disappointing first-round loss following a first-place finish in the Central Division, Murray left the GM’s post as well to join the Florida Panthers, with Devellano returning to the general manager’s position.

17 Mike Vernon was one of the NHL’s most successful goaltenders in the late 1980s and early 1990s with the Calgary Flames. He helped get the Flames to the Stanley Cup Final in 1986, and three years later earned all 16 wins when Calgary capped a spectacular season by avenging their loss to the Montreal Canadiens in the Final three years earlier.

The Flames failed to repeat in 1990, and the team selected goaltender Trevor Kidd in the first round of the 1990 NHL Draft with the idea that he would become Vernon’s replacement. After the Flames finished first in the Pacific Division during the regular season, they were upset by the Vancouver Canucks in the opening round of the playoffs, with Vernon going 3–4.

Kidd played 31 games in 1993–94, and the Flames felt he was ready to handle the starting job. That made Vernon expendable. The Red Wings, who were coming off a stunning first-round upset by the San Jose Sharks, felt they needed to make a change as well. The result: On June 29, 1994, the Red Wings traded defenseman Steve Chiasson to the Flames for Vernon.

Vernon got most of the starts in the lockout-shortened 1994–95 season, going 19–6–4 and helping the Red Wings win the Presidents’ Trophy as the top team in the regular season. With Vernon carrying the load in goal, the Red Wings advanced to the Stanley Cup Final for the first time since 1966, only to be swept by the New Jersey Devils.

After some cantankerous negotiations, Vernon and the Red Wings agreed on a two-year contract. But he played just 32 games in 1995–96, with youngster Chris Osgood getting more playing time. When Vernon did play, he was superb, finishing 21–7–2 with a 2.26 goals-against average for a team that set an NHL single-season record for wins and led the NHL with 131 points. But Vernon played just four games during the playoffs, going 2–2 before the Wings were eliminated by the Colorado Avalanche in the Western Conference Final.

Vernon was Osgood’s backup for most of 1996–97, going 13–11–8 during the regular season. But Osgood struggled down the stretch, and coach Scotty Bowman announced that he would be going with Vernon in the playoffs.

The move worked better than anyone could have dreamed. Vernon went 16–4 with a 1.76 goals-against average, helping the Red Wings end a 42-year drought with their first Stanley Cup championship since 1955.

Unfortunately, the Red Wings then found themselves in a position in which they were likely to lose a goaltender in the NHL Waiver Draft. Rather than lose Vernon for nothing, they traded him to the San Jose Sharks for draft picks on August 18, 1997.

18 In addition to his performance on the ice, Ted Lindsay’s NHL legacy includes his work helping to organize the NHL Players’ Association. His willingness to take a stand and try to improve the lot of NHL players took a toll on his career (he was still among the league’s elite players when he was exiled to the Chicago Black Hawks in 1957), so it’s appropriate that the NHLPA’s award for the most outstanding player in the regular season, which was established in 1971 as the Lester B. Pearson Award, was renamed in his honor in 2010.

Two Red Wings have taken home the trophy.

Though NHL voters named Wayne Gretzky of the Los Angeles Kings as winner of the Hart Trophy, given to the league’s most valuable player, Detroit’s Steve Yzerman was voted as the NHL’s outstanding player by his fellow players in 1989 (when the award was still the Lester B. Pearson). Yzerman had had his greatest offensive season, finishing with 65 goals, 90 assists, and 155 points, finishing third in all three categories. He led the NHL in even-strength goals with 45 and in shots on goal with 388. He was third in balloting for the Hart Trophy, but first in the voting among his fellow players.

Yzerman inadvertently had a hand in the Red Wings’ other winner. He missed nearly one-third of the 1993–94 season with injuries, giving Sergei Fedorov a chance to play top-line minutes. Fedorov took the opportunity and ran with it, finishing with 56 goals, 64 assists, 120 points, and a plus-48 rating to help the Red Wings finish first in the Central Division.

Yzerman was among those who were impressed by Fedorov’s performance.

“I’ve only seen two other players that can dominate a game like Sergei, and that’s Wayne and Mario,” he said, referring to Gretzky and Lemieux. “In my opinion, he’s the best player in the League. He is different than Wayne and Mario, because he dominates with his speed and unbelievable one-on-one moves.”

Unlike Yzerman five years earlier, Fedorov in 1994 won both the Hart and the Pearson (now Lindsay) awards, capping off a truly remarkable breakout season.

19 The 1999–2000 season was Steve Yzerman’s 17th in the NHL, and, not surprisingly for a player of his caliber and career length, it contained three major milestones, all of which he reached during a nine-day span in late November.

Yzerman scored his 599th goal and earned his 900th assist on November 17, 1999, when the Red Wings extended their unbeaten streak to five games by defeating the Vancouver Canucks. He became the 10th player in NHL history to have 900 assists, and the two-point night increased his career total to 1,499, eighth on the all-time list.

Point number 1,500 came three nights later, when he had an assist on a goal by defenseman Mathieu Dandenault in a 2–1 road loss to the Edmonton Oilers.

Yzerman became the 11th player in NHL history to reach the 600-goal mark when he scored during the Red Wings’ 4–2 win against the Oilers at Joe Louis Arena on November 26, 1999.

It wasn’t exactly a thing of beauty. Yzerman took a pass from Nicklas Lidstrom, skated along the goal line, and lifted a shot that bounced off the back of goalie Tommy Salo’s leg and into the net.

“I just picked up a loose puck,” Yzerman said. “Ideally, I would have drawn it up a little prettier than that. But I’ve gotten some lousy goals over the years, too.”

Yzerman joined Wayne Gretzky, Gordie Howe, Marcel Dionne, and Mark Messier as the only NHL players at the time with 600 goals and 900 assists.

All in all, a pretty good month.

Yzerman finished the season with 75 career game-winning goals and would get 19 more before he retired in 2006.

20 Perhaps the most amazing thing about Nicklas Lidstrom winning the Norris Trophy seven times is that the first one didn’t come until he had passed his 30th birthday; he was 31 by the time he actually received the trophy. In comparison, Bobby Orr, the all-time leader in winning the Norris Trophy with eight, had retired a few months after his 30th birthday because of knee injuries.

Lidstrom was an NHL First-Team All-Star in each of the three seasons before 2000–01, when he won the Norris for the first time. He finished with 15 goals and 71 points in 82 games, averaging 28:27 of ice time. He was also voted a First-Team All-Star for the fourth straight season, and, for the third season in a row, he was the runner-up for the Lady Byng Trophy.

Though Lidstrom’s offensive numbers were down in 2001–02 (nine goals, 59 points), he was again the engine that made the Red Wings go—this time, all the way to their third Stanley Cup in six seasons. He averaged 28:49 of ice time in 78 games and added to his hardware haul by winning the Conn Smythe Trophy as playoff MVP.

Lidstrom made it three in a row in 2002–03, finishing with 18 goals, 62 points, and a plus-40 rating while averaging a career-high 29:20 of ice time—meaning he was on the ice for almost half the game, every game. He was also chosen a First-Team All-Star for the sixth straight season.

After a subpar (for him) season in 2003–04 and a lockout that canceled the 2004–05 season, Lidstrom began another run of three straight Norris Trophy wins in 2005–06. He finished with a career-high 80 points (16 goals, 64 assists), was plus-21, and averaged 28:07 of ice time—at age 35.

He won again in 2006–07 after finishing with 62 points (13 goals, 49 assists) and another plus-40 rating while averaging 27:29 of ice time. Norris number six came in 2007–08, when he scored 10 goals and had 70 points as well as a plus-40 rating. He was voted a First-Team All-Star for the ninth time.

Only Bobby Orr won the Norris Trophy more often than Nicklas Lidstrom. (By Michael Miller—Own work; License: CC BY-SA 3.0; Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18250480)

In each of the next two seasons, Lidstrom had to settle for being a Second-Team NHL All-Star. He was third in the Norris balloting in 2008–09 and fourth in 2009–10. But despite finishing with a minus-2 rating in 2010–11 (the only time in his NHL career he wasn’t a “plus” player), Lidstrom equaled Doug Harvey by winning the Norris for the seventh time. He finished with 16 goals and 62 points while averaging 23:28 of ice time—pretty good for a 40-year-old.

Lidstrom retired after one more season. He finished fifth in the Norris balloting after putting up 34 points (11 goals, 23 assists) and a plus-21 rating in 70 games.

21 The Lady Byng Trophy actually predates the Wings’ arrival in the NHL. It was donated to the league by Evelyn Byng, wife of Canada’s governor general at the time, and was to be given to the player “adjudged to have exhibited the best type of sportsmanship and gentlemanly conduct combined with a high standard of playing ability.”

The award was first given to Frank Nighbor of the Ottawa Senators after the 1924–25 season. New York Rangers center Frank Boucher won it so often—seven times in eight seasons from 1927–35—that he was actually given permanent custody of the original trophy and a new one was made.

Forward Marty Barry was the first member of the Red Wings to win the award, in 1937, after finishing with six penalty minutes in 47 games (the NHL season at the time was just 48 games).

No Red Wing won the Lady Byng again until 1949, when Bill Quackenbush became the first defenseman to win the award. Quackenbush, a member of the Hockey Hall of Fame, became the second winner to go through a whole season, 60 games in 1948–49, without taking a single penalty. But Quackenbush was more than just a gentlemanly player. He finished the season with six goals and 23 points and was named a First-Team NHL All-Star for the second straight season.

Despite all that, Quackenbush found himself elsewhere before the 1949–50 season began. On August 29, 1949, he was sent to the Boston Bruins in a six-player trade. One of those players, Pete Babando, scored one of the most famous goals in NHL history, the double-OT tally that won the 1950 Stanley Cup.

Quackenbush played seven seasons for the Bruins before retiring, finishing in the top four in voting for the Lady Byng three times.

Two years later, another Red Wings defenseman began a run in which he won the Lady Byng three times in four years.

Red Kelly joined the Wings as a 20 year old in 1947–48 and was an instant hit as a smooth-skating, puck-moving defenseman. He was often partnered with Quackenbush. A Second-Team All-Star and the Lady Byng runner-up in 1950, he then had an even better season in 1950–51, finishing with 54 points (17 goals, 37 assists) and 24 penalty minutes to earn a berth on the First All-Star team and win the Lady Byng.

“Joe Primeau had trained me very well,” Kelly said years later, referring to his junior coach, “so when I went to the NHL, I had been taught the things I should have been taught and I didn’t have to learn them when I went up there.”

One of those things he learned was that you can’t contribute from the penalty box. In his three Lady Byng seasons, he took a combined total of 50 penalty minutes.

Kelly was a First-Team All-Star and the Lady Byng runner-up in 1952, then won the trophy again in 1953 and 1954 while again earning a First-Team All-Star berth. In 1954, he also became the first winner of the Norris Trophy, a new award given to the NHL’s top defenseman.

22 Gordie Howe led the Red Wings and the NHL in scoring for four consecutive seasons. from 1950–51 through 1953–54, before finishing second on the team to Dutch Reibel in 1954–55.

But Howe was back on top in scoring among the Red Wings in 1955–56, piling up 38 goals and 79 points in a 70-game season. From then until 1969–70, Howe won two more NHL scoring titles, finished in the top five in the league in scoring every season, and led the Red Wings in points 13 times.

Howe had at least 72 points (in a 70-game season) and led the Wings in scoring for nine consecutive seasons, when he finished second to a young center named Norm Ullman.

Ullman joined the Wings in 1955–56 and soon became one of the NHL’s most consistently productive players. He had seven straight 20-goal seasons and put up at least 50 points in eight consecutive seasons through 1963–64.

In 1964–65, Ullman had a career year. He went from 21 goals to 41 and from 51 points to 83. That put him ahead of Howe, who had 29 goals and 76 points. Ullman was second in the NHL in scoring behind Chicago’s Stan Mikita (87 points); Howe came in third.

Howe finished first on the Wings in scoring in 1965–66, but, in 1966–67, Ullman again finished ahead of Howe with 70 points, five more than Howe. Ullman finished third in the NHL in scoring behind Chicago teammates Mikita (97 points) and Bobby Hull (80), while Howe tied for fourth with another Black Hawk, Kenny Wharram.

Ullman had 30 goals and 55 points through 58 games in 1967–68 when he was sent to the Toronto Maple Leafs in one of the biggest trades in NHL history. He finished the season with a combined total of 35 goals and 72 points; Howe led the Wings with 39 goals and 82 points.

Howe led the Wings in scoring in each of the next two seasons, before finishing with 52 points in 1970–71, his final season in Detroit.

23 Even in today’s NHL, where games no longer end in ties, 40 wins are a lot. In the past 70 years, three Red Wings goaltenders won as many as 40 games once: Roger Crozier, who won 40 in 1964–65, and Dominik Hasek, who had 41 victories in 2001–02 before helping the Red Wings win the Stanley Cup.

Chris Osgood came close with 39 wins in 1995–96; Hasek (2006–07) and Tim Cheveldae (1991–92) each won 38. Glenn Hall also had 38 wins, his coming in 1955–56.

But the only Detroit goaltender to finish a season with 40 or more victories more than once is Terry Sawchuk, who did it three times in a span of five seasons beginning in 1950–51.

Detroit entered that season as the defending Stanley Cup champion. But the Wings also had a new starting goaltender. Though they’d won the Cup the previous spring with Harry Lumley between the pipes, Sawchuk had been impressive during a seven-game call-up during January 1950 while Lumley was injured. GM Jack Adams traded Lumley to the Chicago Black Hawks during the offseason, and the Wings entered the season with an untested rookie goaltender. But Sawchuk was every bit as good as the Red Wings could have hoped for—and more.

Sawchuk played every minute of the 1950–51 season and set an NHL for victories by winning 44 games. He went 44–13–13 with a 1.97 goals-against average and 11 shutouts, helping the Red Wings finish first in the regular season. He won the Vezina Trophy, then given to the goaltender on the team that allowed the fewest goals, as well as the Calder Trophy as the NHL’s top rookie.

If there were any doubts that his rookie season was no fluke, Sawchuk dispelled them by matching his own single-season record for victories by winning 44 games in 1951–52, again helping the Red Wings win the Prince of Wales Trophy, then given to the regular-season champion. He was 44–14–12 with a 1.90 GAA and 12 shutouts.

Unlike 1950–51, when the Red Wings were upset in the Semifinals, the 1951–52 season ended with another Stanley Cup championship. Had there been a Conn Smythe Trophy awarded at the time, Sawchuk would probably been a shoo-in: He allowed five goals in eight games (0.63 GAA) and had four shutouts.

Sawchuk’s goals-against average was below 2.00 in each of the next two seasons and he led the NHL in victories, but he won “only” 32 games in 1952–53 and 35 in 1953–54.

His third 40-win season came in 1954–55. Sawchuk went 40–17–11 with a 1.96 GAA and 12 shutouts (the third time in four seasons he’d had a dozen). He capped the season by going 8–3 in the playoffs, helping the Red Wings win the Cup for the fourth time in six seasons.

But just as Sawchuk’s promise had persuaded the Wings to trade away a Cup-winning goaltender in Lumley, the Red Wings were enamored of backup Glenn Hall and felt Sawchuk was expendable. He was traded to the Boston Bruins on June 3, 1955. Though Hall did end up being as good as the Wings had hoped, they didn’t win the Stanley Cup in his two seasons as the starter, and Detroit reacquired Sawchuk in July 1957. Sawchuk played in the NHL until 1970, but never won more than 29 games in a season again.

24 It’s a hard concept to grasp now, but in the Original Six era, most teams carried just one goaltender. The home team might have a spare goalie, sometimes a team trainer, sometimes a minor leaguer, on hand if either goaltender got hurt during a game. But basically, a team carried one goaltender who was expected to play as many games as possible, including back-to-backs, three games in four nights, etc.

By the time Dominik Hasek joined the Wings in 2001, there was no expectation that a goaltender would play every game. Hasek’s 65 games were a little above the norm for a top-flight starting goaltender. But with 41 wins and a 2.17 goals-against average, it proved to be the perfect workload to have him ready for the Stanley Cup Playoffs, when he led the Wings to their third championship in six seasons.

The last Detroit goaltender to play in every game during a season was Roger Crozier, who appeared in all 70 games during 1964–65—but Crozier didn’t finish all of them. Crozier was 40–22–7 and played 4,166 of a possible 4,200 minutes. Carl Wetzel, a longtime minor league goaltender, got into two games and was the loser in relief against the Montreal Canadiens on December 26, 1964, allowing four goals on 18 shots.

Glenn Hall literally never missed a minute during his two seasons with the Red Wings. He started all 70 games and played 4,200 minutes in 1955–56 and 1956–57 after taking over the starting job when the Wings traded Terry Sawchuk to the Boston Bruins. He went 68–44–28 during that span.

Sawchuk played every minute of the Red Wings’ 70 games in 1950–51, and again in 1952, winning 44 games each time and posting a goals-against average below 2.00 each time. He played 63, 67, and 68 games in the next three seasons with the Wings, again finishing with a GAA below 2.00.

The Red Wings brought Sawchuk back in 1957, two years after they had traded him to the Boston Bruins for Johnny Bucyk. Sawchuk matched Hall in terms of showing up for work every night, starting and finishing all 70 games. However, the magic he’d had in his first stint with the Wings wasn’t there. He finished the 1957–58 season 29–29–12 with a 2.94 goals-against average.

No Detroit goaltender since then has played every minute of every game—and given the longer schedule and travel of today’s NHL, it’s safe to say no one ever will.

25 The Red Wings reached double figures in goals for first time by holding a Christmas party, with the Toronto Maple Leafs as the unwilling guests. The Wings routed the Leafs, 10–1, at the Olympia on December 25, 1930.

The first road game in which the Red Wings reached double figures took place on December 13, 1934, when the Wings pummeled the St. Louis Eagles, 11–2. It was the only NHL season for the Eagles, who had relocated from Ottawa and folded after 1934–35.

The Wings had one double-figure night each in 1941–42 and 1942–43, then had three in each of the following two seasons. That included the biggest shutout win in NHL history, a 15–0 demolition of the New York Rangers on January 23, 1944. It was one of five times in a span of three seasons that the Wings scored 10 goals or more against the Rangers.

The Red Wings hit double figures three times during the 1952–53 season, the last on March 2, 1953, when they routed the Boston Bruins, 10–2, at the Olympia. That was their last 10-plus goal game until March 18, 1965, when they drubbed Boston, 10–3.

Detroit reached double figures just once more in the 1960s and twice in the 1970s, but then did it 12 times in a span of 15 seasons from 1981–82 through 1995–96. Among those games was a 12–0 victory against the Chicago Blackhawks on December 4, 1987, the biggest margin of victory for the Wings during their time at Joe Louis Arena.

The Red Wings haven’t reached double figures in a home game since November 27, 1993, when they defeated the Dallas Stars, 10–4. They won, 10–3, at the San Jose Sharks on January 6, 1994, the fourth time they had scored 10 or more goals in a road game.

The last time Detroit hit double figures on the road was December 2, 1995, when they embarrassed the Montreal Canadiens, 11–1, at the Forum. Slava Kozlov scored three times for the Wings, who had nine times on 26 shots against Patrick Roy before the furious goaltender was removed. (Roy never played for the Canadiens again and was dealt to the Colorado Avalanche a few days later.)

Since then, the Red Wings have allowed 10 goals in a game twice. They lost, 10–3, to the St. Louis Blues at Joe Louis Arena on March 30, 2010, and 10–1 to the Canadiens at Montreal on December 2, 2017.

26 Few defensemen score three goals in an NHL game. Nicklas Lidstrom, a first-ballot Hall of Famer, did it exactly once in his career, on December 15, 2010, against the St. Louis Blues.

Since the NHL’s first expansion in 1967, three players have accounted for the five hat tricks scored by Red Wings defenseman.

When Lidstrom got his, he was the first Detroit defenseman to score three goals in a game since Reed Larson had done it on February 27, 1985, when he got three in an 11–5 victory against the Vancouver Canucks. Larson had scored three times in a game twice before, each in a road game against the Pittsburgh Penguins, the first in a 6–4 loss on January 3, 1981, and again in a 7–3 win on February 15, 1983.

But the most recent hat trick by a Red Wings defenseman belongs to Mike Green, who scored three times in a 5–1 win against the Ottawa Senators at Joe Louis Arena on October 17, 2016.

Green was a prolific offensive contributor for most of the first decade of his NHL career while playing for the Washington Capitals. He’s the last defenseman to score 30 goals in a season (31 in 2008–09) and had back-to-back 70-point seasons in 2008–09 (76) and 2009–10 (73).

Green scored his first goal of the 2016–17 season when he wired a wrist shot over the shoulder of Senators goaltender Andrew Hammond at 11:43 of the first period, giving Detroit a 1–0 lead. After Darren Helm made it 2–0 at 14:15, Green got his second of the game at 17:17, slipping down from the point into the high slot and one-timing a pass from Thomas Vanek past a screened Hammond.

After Ottawa’s Ryan Dzingel scored the only goal of the second period to make it 3–1, Green completed his hat trick at 13:24 of the third period. Riley Sheahan won a puck battle in the right corner, and Luke Glendening fed Green at the right point. Green took advantage of some open space to drift into the high slot and beat Hammond with a wrist shot through traffic, setting off a cascade of hats onto the ice.

Green finished the 2016–17 season with 14 goals, the most he’d scored in one season since getting 19 with the Capitals in 2009–10.

27 The Red Wings qualified for the Stanley Cup Playoffs for the first time in 1928–29, their third season in the NHL. They finished third in the American Division with a 19–16–9 record, the first time they finished over .500. That earned the Wings a first-round series against the Toronto Maple Leafs, who had finished third in the Canadian Division. Each team finished the season with 52 points, but the Leafs disposed of the Wings easily, winning, 3–1, in Detroit and 4–1 at Toronto to take the total-goals series, 7–2.

It took the Wings three years to get back into the playoffs. Detroit finished fourth in 1929–30 and 1930–31. The Red Wings were below .500 again in 1931–32 but ended up third in the four-team American Division with a record of 18–20–10. They played the Montreal Maroons, who had finished third in the Canadian Division, in the first round, but again came up short in a total-goals series. The teams played to a 1–1 tie on March 29, but Detroit lost, 2–0, in Montreal two nights later, giving the Maroons a 3–1 victory.

The 1932–33 season was the most successful in team history to that point. The Red Wings finished 25–15–8, tying the Boston Bruins for first place in the American Division (the Bruins finished first on tiebreakers). The Maroons, second in the Canadian Division, were again Detroit’s opponent in the Quarterfinals, a two-game, total-goals series—but this time the result was different.

The series opened in Montreal on March 25, 1933, and Detroit goaltender John Ross Roach was perfect. Goals by Larry Aurie and Carl Voss were more than enough support in a 2–0 victory that gave the Wings their first victory in a playoff game.

Three nights later at the Olympia, the Maroons jumped to a 2–0 lead when Hooley Smith scored twice midway through the second period. But Herbie Lewis got one goal back in the final seconds of the second period, Ebbie Goodfellow tied the game, 2–2, at 3:47 of the second period, and John Gallagher’s goal with 4:06 remaining gave Detroit a 3–2 win and a 5–2 margin in goals.

The Wings came up short in the Semifinals against the New York Rangers, losing, 2–0, in New York on March 30 and 4–3 at the Olympia three nights later.

28 Gordie Howe played 1,687 games with the Red Wings, the most in franchise history. However, his return to the NHL with the Hartford Whalers removed him from the list of players who’ve played 1,500 or more NHL games and spent their entire career with one team. Howe does hold the league record for games played with 1,767; the final 80 came with the Whalers in 1979–80.

Entering the 2018–19 season, 18 players have played 1,500 or more regular-season games in the NHL. Three of the four who spent their entire careers with one team did so with the Red Wings; five more members of the 1,500-game club spent parts of their careers with Detroit.

Defenseman Nicklas Lidstrom is 12th on the all-time list with 1,564 games played, but he holds the NHL record for games played in a career spent with one team. Lidstrom, Detroit’s third-round pick in the 1989 NHL Draft, made his NHL debut in 1991–92, finishing with 60 points (11 goals, 49 assists), while playing in all 80 games.

Lidstrom played every game in each of the next two seasons and didn’t miss a game until 1994–95, when he played 43 of 48 games in a lockout-shortened season. For the next 11 seasons, Lidstrom didn’t miss more than three games in any season. He played 76 of the 82 games in 2007–08 and 2008–09, then played in all 82 games in each of the following two seasons. Not until 2011–12, his final season, did Lidstrom miss more than six games, playing 70 of Detroit’s 82 games.

Like Lidstrom, Alex Delvecchio was both skilled and durable. He made his debut by playing one game in the 1950–51 season, became an NHL regular the following season, and remained one until retiring after playing 11 games in 1973–74, giving him 1,549 during a career that earned him induction into the Hockey Hall of Fame.

Delvecchio played 65 of 70 games in 1951–52, his first full NHL season, and missed a total of two games in the next four seasons. After being limited to 48 games in 1956–57, Delvecchio played all 70 games in each of the next seven seasons. He missed two games in 1964–65, then played every game in each of the next three seasons.