He that upon pretended malice, shall murther or take away the life of any man, shall bee punished with death.

No man shal commit the horrible, and detestable sins of Sodomie upon pain of death; and he or she that can be lawfully convict of Adultery shall be punished with death. No man shall ravish or force any woman, maid or Indian, or other, upon pain of death.

—Articles, Lawes, and Orders, Divine, Politique, and Martiall for the Colony in Virginea, first established by Sir Thomas Gates Knight, Lieutenant General, on May 24, 1610

Odd as it may seem, the prison system in the United States, now straining at the seams and ripe for reforms, came into being as a reform itself of corporal and capital punishment. The merits and faults of capital punishment have been debated from Plymouth Rock to Capitol Hill, with great passion and without resolution. The Supreme Court, the ultimate arbiter of constitutionality, has grappled with the legitimacy of the death penalty since 1879.1 The Court has banned “cruel and unusual punishment,” forbidden by the Eighth Amendment, but struggles with the definition of that term and its application to capital punishment. It is a struggle that has its roots deep in the country's history.

The first known execution on what is now American soil occurred in 1608. Captain George Kendall was put to death on charges of spying for Spain; the execution was by firing squad. Fourteen years later, Daniel Frank was hanged in Jamestown for stealing a calf; this execution was the first sanctioned by colonial law and was carried out by a hangman.

The first murderer to be put to death was John Billington, a pilgrim on the Mayflower known as a troublemaker even before he set foot in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In 1630 Billington killed a neighbor and was, in the words of Governor William Bradford, “both by grand and petty jury found guilty of willful murder, by plain and notorious evidence.”2 Billington died by the noose, which became the preferred method of execution as other colonies moved to implement capital punishment. By the time the colonies joined together to rise up against King George, most of them had established death as the penalty for a host of crimes ranging from murder to counterfeiting, arson, rape, and horse theft.

After the colonies gained their independence, fresh voices were heard on the issue of capital punishment. In Virginia, Thomas Jefferson proposed limiting capital punishment to the crimes of murder and treason. The legislature initially defeated the measure but narrowed capital offenses several years later. The limitations didn't prevent the commonwealth from keeping its executioners busy for the next two centuries: Virginia leads the nation with 1,386 executions since 1608.3

Early in our history, there were a dozen executions carried out by “breaking on the wheel,” six by gibbeting (hanging the criminal's body in public for weeks or months after execution), and sixty-six by burning. Firing squads accounted for 144 executions, including three in modern-day Utah.4 Hanging, however, was the predominant instrument of execution throughout the United States until the 1920s. It was also the method used by vigilantes, racists, and unruly mobs—but those lawless instances are more properly categorized as “lynchings” and are outside the scope of this book.

Execution by hanging was a public spectacle for many years, often a raucous and rowdy event. Contemporary accounts used such terms as drunken frenzy and carnival of brutality to describe them.

The last public hanging in West Virginia occurred in 1897 in the Jackson County seat of Ripley, population five hundred. Arriving on horseback or wagons, an estimated five thousand people came from sixty miles around, from five surrounding West Virginia counties and one in Ohio, to see a murderer named John Morgan hanged by the sheriff. According to an eyewitness account in the Jackson Herald, the party atmosphere started two days early:

Ripley is a temperance town. It is against the law to sell any liquor there, but there isn't any law against drinking it…. Let the reader imagine a town built around a public square covering perhaps five acres…. Fill the square with men, women and children…some of the women with babies in their arms…and punctuate that part of the turmoil with the loud shrieks of a hundred or more youthful fakirs on foot, each with a bundle of printed matter in his arms and each shouting, “Last and only true confession of John F. Morgan.” “Here you are, only 5, 10, 15 cents,” as the case might be.5

The crowds aside, the general public attitude toward hanging was not enthusiastic. Death on the gallows could be an untidy process: incorrect placement of the rope or a miscalculation of the prisoner's “drop” resulted in some agonizingly slow deaths. There were cases where the rope broke, resulting in a second hanging; there were also several decapitations.

A new method of execution, one that held out the promise of less cruelty and more certainty than hanging, had its roots in an accidental electrocution in Buffalo, New York.

There, in 1881, a dentist named Alfred P. Southwick heard an interesting story from the local coroner, an acquaintance of his and fellow amateur scientist. The coroner had just conducted an autopsy on a man who had, while intoxicated, stumbled against a generator terminal in a power plant. The coroner was struck by the immediacy and apparent painlessness of the man's death, and Southwick, who clearly had a macabre side to his personality, saw a possible application of electricity to the business of execution. He thought that electrocution could be a more humane form of execution than the gallows.

To explore his theory, Southwick built a miniature electrocution chamber and volunteered his services to the Buffalo Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Up until this point, the society had been disposing of hundreds of stray dogs and cats each year by placing them in bags and submerging them in Lake Erie. It took some grisly trial and error on the part of the experimenters, but soon Southwick's machine was declared a success.

Southwick had an engineering background and strong political connections, and he employed them both in order to push for a government study to investigate the application of the new method to state executions. A three-man commission (on which Southwick served) unanimously reported that electrocution was “the most humane and practical method of carrying into effect the sentence of death.”6 The state legislature agreed.

What followed was a study in brawling egos and cutthroat commercial competition. Thomas Edison, the father of electricity, had a huge stake in direct current (DC), with which much of Manhattan was wired. George Westinghouse had discovered a way to produce alternating current (AC), a form of electricity that could be more easily and widely distributed. Neither man wanted his product to be used for executions, and both mounted political and public-relations wars to protect their “brands.”

Edison won. His canny campaign resulted in the selection of alternating current for the new electric chair being installed at Auburn State Prison. But Westinghouse didn't go down without a final, novel legal battle—which he conducted by proxy.7

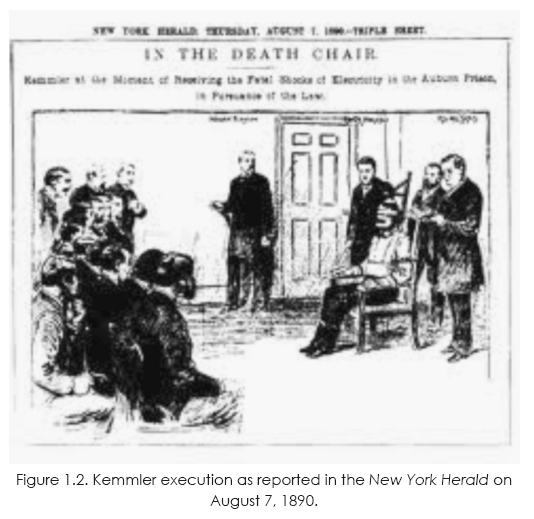

The first person condemned to death under the new New York State law was William Kemmler, who had confessed to the murder of his girlfriend. He went to court not to prevent his execution, but rather his electrocution. His lawyers, apparently surreptitiously paid by Westinghouse, argued that the electric chair constituted cruel and unusual punishment. The litigation went all the way to the United States Supreme Court, which ruled unanimously that death by the electric chair was not inhumane. The Supreme Court upheld the trial court's view of electrocution as “in keeping with the scientific progress of the age.”8

The New York Times described what followed as “a disgrace to civilization”:

After the initial jolt of electricity, Kemmler was pronounced dead by the attending physician. But as Warden Durston began to remove the electrode from Kemmler's head, the condemned man began to breathe. Durston reattached the electrode and signaled for another burst of electricity. The Times reporter described what happened next:

Again came that click as before, and again the body of the unconscious wretch in the chair became as rigid as one of bronze. It was awful, and the witnesses were so horrified by the ghastly sight that they could not take their eyes off it…. An awful odor began to permeate the death chamber, and then, as to cap the climax of this fearful sight, it was seen that the hair under and around the electrode on the head and the flesh under and around the electrode at the base of the spine was singeing. The stench was unbearable.9

After the second jolt of electricity, Kemmler was again pronounced dead. This time, the doctor was right.

George Westinghouse felt vindicated. He told the New York Times, “It has been a brutal affair. They could have done better with an axe.”10

The experience did not cause New York State authorities to shut down the electric chair; instead, technical procedures were reworked. On the morning of July 7, 1891, they confidently threw open the doors of a new execution chamber at Sing Sing prison in Ossining, thirty-five miles north of New York City, and invited the press to witness a marvel of efficiency: four executions in a row, conducted within just two hours.

New York's innovation attracted the attention of legislators across the country. Over the course of the next two decades, fourteen more states wired up their own electric chairs; by 1950 electrocution had spread to twenty-five jurisdictions. The new method was initially less popular in the American West, where hanging remained the political and cultural choice, but electricity became the dominant preference for execution chambers in the rest of the nation.

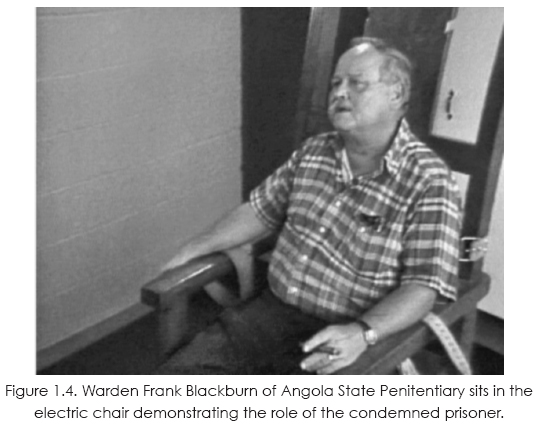

The “humaneness” of electrocution was under continuing attack by death-penalty opponents over the years, but the method had strong defenders with firsthand experience. The authors met one of them, Warden Frank Blackburn of Louisiana's Angola Penitentiary, in 1985. Blackburn, who oversaw the execution of four prisoners during his tenure, said the chair was humane and efficient: “I think the electrical chair, the electricity, the voltage, and so forth that we have here, it's instantaneous,” he said in an interview that took place in the tiny building known as the Death House, which housed the state's electric chair, known as “Gruesome Gertie.”11

Blackburn told us the key was planning and preparation. During the interview, he was totally relaxed, chomping on a long cigar, as he took the role of a condemned prisoner and eased himself into the Gruesome Gertie's seat to demonstrate the process.

“We have what we call our strap-down people. And we'll select an employee of about the same height and the same weight of the inmate that's to be executed, and the whole purpose is to test the straps, to make sure the chair is still, you know, firm and things of this sort.” When asked if he'd ever had a botched execution, Blackburn said, “We've had no problems.”12

|

To see the interview with Warden Blackburn and a video report on the electric chair, go to: http://murderatthesupremecourt.com/blackburn |

That electric chair is no longer in the Death House; it was last used in 1991 and is now on display in the prison's museum. Gruesome Gertie and many of her counterparts in other states have been retired in favor of the gurneys and crucifix-shaped tables used for executions by lethal injection. However, lethal injection did not immediately displace the electric chair as the most widely used method of execution.

In the search for “more humane” methods, eleven states adopted the use of lethal gas for varying periods of time. In this procedure, cyanide gas would be generated when the executioner threw a remote lever to drop pellets of cyanide into a bucket of acid in a sealed chamber. The chemical reaction produced a toxic gas that is fatal when inhaled. San Quentin State Prison's Clinton Duffy, the warden who presided over gas-chamber executions ninety times, from 1940 to 1952, said the executioner liked gas better than the electric chair “because he didn't feel so directly responsible for the death of the condemned.”13

The unspoken element in the search for “more humane” methods of execution was the effect on executioners, prison staff, and witnesses, not simply the pain of the condemned. For many, lethal injection fit the bill.

The process of deliberate death through chemistry goes back through recorded time at least to Socrates. The men who would concoct a modern framework for its use in executions were two Oklahoma doctors named A. Jay Chapman and Stanley Deutsch. Chapman was the state's chief medical examiner and Deutsch, an anesthesiology professor. The recipe called for poison that would stop the heart after an injection of quick-acting barbiturates that would put the condemned prisoner to sleep. “Having administered these drugs for approximately 20 years, I can assure you that this is a rapid, pleasant way of producing unconsciousness,” wrote Deutsch.14

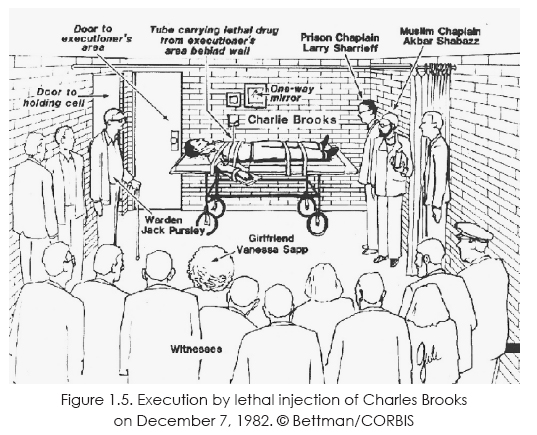

Oklahoma was the first state to officially adopt lethal injection, but Texas carried out the first execution. On the night of December 6, 1982, forty-year-old Charles Brooks Jr. ate a final meal of steak, french fries, ketchup, Worcestershire sauce, biscuits, peach cobbler, and iced tea at the “Walls Unit” of the Texas State Penitentiary in Huntsville. Just after midnight, he was rolled into the new execution chamber on a gurney, connected to an intravenous tube, and put to death. The drugs were injected at 12:09 a.m., and Brooks was pronounced dead at 12:16 a.m.

One of the witnesses, Dick Reavis of Texas Monthly magazine, said that after the anesthetic began to enter Brooks's body, “he moved his head as if to say ‘no.’ Then he yawned and his eyes closed, and then he wheezed. His head fell over toward us, then he wheezed again.”15

Lethal injection came to Louisiana's Angola Penitentiary in 1993, under the administration of Warden Burl Cain. Cain is a supporter of the method and an advocate of capital punishment. He has put seven prisoners to death at Angola. A gurney sits where Gruesome Gertie was once installed, and Cain took Barbara Walters for a tour of the Death House in 2001. He said that a condemned prisoner is startled by the sight of that gurney. “When he sees it for the first time, the reaction is, it shocks him,” Cain said, “literally shocks him. And you immediately think of the victim. That's how the victim probably felt when he had the gun to their head, or whatever he used to kill them, at their last minute. Then he sees it and he feels what they felt.”

Death comes quickly. “He's going to breathe two breaths,” Cain told Walters. “Pshh. Pshh. It's not painful at all, I wouldn't think.” Cain says most prisoners ask to hold his hand. “What can I say?” he asked, adding that he's been tempted to respond. “But who held the victim's hand?”

“I think of that, you know,” Cain said. “But I have to think, I'm here with him. I couldn't be with the victim.” He says he'll signal to the executioner to begin the flow of chemicals, then turn to the prisoner and speak the last words he will ever hear: “Get ready to see Jesus’ face. Here we go.”16

|

For the interview with Warden Cain and a visit to the Angola Death House go to: http://murderatthesupremecourt.com/cain |

At this writing, capital punishment is on the books of thirty-three states. There are more than 3,100 condemned prisoners on the death rows of those states. Many of them have been behind bars for years; some will die of natural causes before their legal remedies are exhausted. The others await a last meal and a warden's final words.