Commissioner Low: It ran too smooth, Ralph, but don't screw it up next time.

Warden Kemp: OK…OK. We appreciate it. Just give us another one.

—command post conversation after the execution of Ivon Ray Stanley in Jackson, Georgia, at 12:24 a.m. on July 14, 1984

Despite the careful oversight of legislators and the dutiful efforts of scientists and penal authorities, mishaps have dogged this country's executions from the scaffold to the gurney. Progress has been no guarantee of perfection. And a number of intriguing stories lie behind the veil of some of America's execution chambers.

The electric chair gained popularity fairly rapidly after its controversial debut with William Kemmler in 1890. Americans admire efficiency, and when the curtain was drawn on New York's execution chamber again, in July of 1891, prison officials electrocuted four prisoners without incident in the space of two hours. “Eminently satisfactory,” proclaimed an eminent physician who witnessed the serial executions.1

The New York innovation attracted the attention of legislators across the country. The new method was initially less popular in the West, where hanging remained the political and cultural choice, but electricity became the dominant preference for execution chambers in the rest of the nation.

Some states, like Louisiana and Mississippi, used travelling electric chairs—powered by generators mounted on trucks—to bring executions to the towns and counties where the condemned had committed their crimes. The theory was that the local community affected by a crime would benefit from proximity to the law's satisfaction and that the specter of a nearby execution would bring home the message of deterrence.

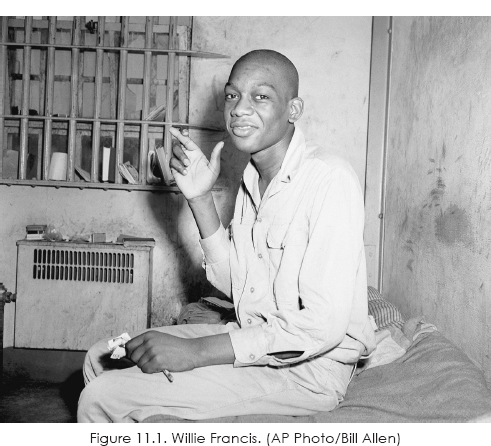

Louisiana's chair, known as “Gruesome Gertie,” suffered a spectacular failure in the rural town of St. Martinville on May 3, 1946. There, with wires strung from a generator truck to a room in the county courthouse, a seventeen-year-old black man, Willie Francis, was seated in the electric chair, rigged with electrodes, and fitted with a black hood. He had been condemned for the murder of the town druggist in a robbery that netted Francis twenty-three dollars.

Dr. Bernard de Mahy, a family practitioner in St. Martinville, was an official witness at the scheduled execution. He told the authors forty years later that he remembered it vividly: “It was a very embarrassing situation for the executioner. Because he said when he threw the switch, ‘Goodbye, Willie’—and Willie didn't leave.”2 The words, and the result, were eerily similar to those at the Kemmler execution fifty-six years before. The chair didn't work.

Willie Francis was unstrapped, stood up, and walked away from the execution room unscathed. Asked what happened, he told bystanders, “The Lord fooled around with that chair.” That phrase became the title of a popular song.

As Francis was led away from the execution site, one of the two technicians who had set up the chair called out to him, “I missed you this time, but I'll get you next week if I have to use a rock.” Both technicians, according to witnesses, had been drinking.3

Bertrand de Blanc, a local attorney, took on Willie as a pro bono client after the aborted execution attempt. With the help of J. Skelly Wright, who would later become a distinguished federal appeals court judge, LeBlanc took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing that to put Willie Francis back in the electric chair would subject him to both double jeopardy and “cruel and unusual punishment.” The Court didn't see it that way. The Court was split 5–4, with Justice Stanley Reed writing for the majority:

We find nothing in what took place here which amounts to cruel and unusual punishment in the constitutional sense…. Petitioner's suggestion is that, because he once underwent the psychological strain of preparation for electrocution, now to require him to undergo this preparation again subjects him to a lingering or cruel and unusual punishment…. The cruelty against which the Constitution protects a convicted man is cruelty inherent in the method of punishment, not the necessary suffering involved in any method employed to extinguish life humanely. The fact that an unforeseeable accident prevented the prompt consummation of the sentence cannot, it seems to us, add an element of cruelty to a subsequent execution.4

Reed's opinion is what is called a plurality opinion because it drew the support of only three other justices—Chief Justice Fred Vinson, along with Justices Hugo Black and Robert Jackson. Justice Felix Frankfurter provided the fifth crucial vote but wrote separately about his misgivings. He was uncomfortable about giving Louisiana a second chance at putting Francis to death but did not view it as unconstitutional. Consequently, he wrote, “this Court must refrain from interference no matter how strong one's personal feeling of revulsion against a State's insistence on its pound of flesh.”5

Behind the scenes, Frankfurter's revulsion was even stronger. In Conference, he told his colleagues: “This is not an easy case…cruel and unusual punishment is a progressive notion, shocking the feelings of the time. Here, though it is hardly a defensible thing for a state to do, it is not so offensive as to make me puke—it does not shock my conscience.”6 But Frankfurter would soon admit that the case “told on my conscience a great deal.” He felt that a second execution might not violate the constitution, but, he said, “I was very much bothered by the problem; it offended my personal sense of decency to do this.”7 So in a highly unusual and extrajudicial move, Frankfurter secretly reached out from the privacy of his ornate Supreme Court chambers to a man he once described as “about the best lawyer South of the Mason Dixon Line,” Monte E. Lemann.8 Lemann had been Frankfurter's roommate at Harvard Law School and was a prominent and politically potent member of the Louisiana bar.

“This case has been so heavily on my conscience that I finally could not overcome the impulse to write to you,” Frankfurter said in a letter to his old friend three weeks after the Court affirmed Francis's death sentence. He asked Lemann to use his political skills to prevent a second execution, saying, “I have little doubt that if Louisiana allows Francis to go to his death, it will needlessly cast a cloud upon Louisiana for many years to come.”9

Frankfurter's furtive move on Francis's behalf—he sent a copy of his letter to only one fellow justice, Harold Burton—was highly unusual, and it provides an intriguing peek behind the mysteries and secrecy of the Supreme Court's inner workings concerning capital punishment. But Frankfurter's efforts failed. Lemann was not able to convince the state's pardons board to make a clemency recommendation; without one, the governor could not act.

So on May 9, 1947, the state's portable electric chair, which would eventually become permanently installed at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, was trucked back to St. Martinville's courthouse. It was, in keeping with the custom of the times, displayed on the courthouse steps for several hours that morning. James Theriot, later the clerk of the parish, told us he remembered coming with his grammar-school classmates to take in the sight. It was, he said, an amazing spectacle: “We were approximately thirteen years old at the time. We left the school during the noon hour so we could come by and visit the chair, which was set right in the middle of the courthouse porch.”10

Early in the afternoon, the chair was moved inside the courthouse and connected to its generator—a new generator, ordered by the governor to prevent an embarrassing repeat of the botched execution attempt. The generator worked. Willie Francis, then eighteen years old, was dispatched successfully. His father had a coffin and hearse on hand, the same coffin and hearse he had brought to the St. Martinville courthouse almost exactly a year before.

The “humaneness” of electrocution was under continuing attack by death-penalty opponents whose cause was fueled by occasionally botched executions. In several states, in fact, condemned men would be “executed” twice, or would die amid flames, smoke, and stench. The authors vividly remember reporting on the case of John Evans in Alabama in 1983. Evans was a hardened criminal convicted of murdering a pawn shop owner after a seven-state crime spree that, by his own admission, involved nine kidnappings and thirty armed robberies. At his murder trial, Evans threatened that if the jury did not sentence him to death, he would escape and murder each of them. They apparently took him seriously: deliberations to convict and execute him took less than fifteen minutes.

Evans, while hardly contrite, accepted his fate. He told us from his cell on death row, “I'm glad it's almost over. And then when I sit in that chair, just before time, I'll be glad it's over.”11

He sat in the chair on April 22, 1983. It was Alabama's first execution in eighteen years, and it did not go well. Russell Canan, Evans's attorney, was a witness. “We had been told that one thirty-second administration of 1,900 volts of electricity would kill and execute John Evans,” Russell told us, “but it took fourteen minutes.”12

“At 8:30 p.m. you could hear the electricity go on,” Canan said. “At that time the electrode that was fastened to his leg burst into flames and sparks. It looked like he was literally being burned alive. He was in fact being tortured and burned alive right before our eyes.” The medical examiner who conducted Evans's autopsy noted considerable burn patterns on the head and left leg. Dr. Gary Cumberland told us, “From the injuries I saw, there would have been an incredible amount of heat generated at these points.” Cumberland said, though, that he thought it was a painless death because of the speed with which electricity brings about unconsciousness.13

The state's chief prison administrator was even more emphatic. Commissioner Fred Smith told us, “He was dead on the first jolt. I am convinced that it was painless and it's the way to go.”14 Skeptics point to the fact that according to prison doctors, John Evans's heart continued to beat, and his lungs to breathe, until the third jolt of electricity was administered in the execution chamber at Holman Prison. He was pronounced dead after that third jolt, at 8:44 p.m.

In the search for “more humane” methods, eleven states adopted the use of lethal gas for varying periods of time. Nevada was in the forefront of this new movement, building a gas chamber in Carson City and executing a Chinese Tong War murderer, Gee Jon, in 1924. “Gee Jon nodded and went to sleep,” reported the Nevada State Journal, “it was as simple and painless as that.”15

But, as with electrocution, this new method experienced some early problems. When in 1936 North Carolina sealed Allen Foster into its execution chamber and released the lethal gas, he gasped and retched convulsively for more than three minutes before losing consciousness, according to the research of legal scholar and author Stuart Banner. He described the warden as “sickened.”16

“Never again for me,” the coroner told a local newspaper. “It's slow torture, and I cannot see anything humane about it.” Another witness said it was “just hell.”17

In California, the gasping and choking suffered by the first two men to be executed in the state's gas chamber were enough to nauseate prison employees who had witnessed hundreds of hangings.18 Banner said the early executions by gas proved to be just as variable as those by electrocution: “Like the electric chair, the gas chamber sometimes inflicted pain, and when it did, the results were just as troubling to watch.”19

As executioners gained experience with lethal gas, the process became more reliably swift and less visibly agonizing. But the unspoken element in the search for “more humane” methods of execution was the effect on executioners, prison staff, and witnesses, not simply the pain of the condemned. San Quentin's Clinton Duffy, the warden who presided over the gas chamber ninety times, said the executioner liked gas better “because he didn't feel so directly responsible for the death of the condemned…. Death by lethal gas was more mechanical,” he said, “which made it less personal.”20

The gas chamber was still regularly attacked as “cruel and unusual” punishment, though such appeals did not gain much traction at the Supreme Court. Public support was growing for an alternative chemical method, lethal injection.

Although he concurred in a 1992 Court decision allowing California to send murderer Robert Alton Harris (Chapter 3) to the gas chamber, Justice John Paul Stevens was troubled. He wrote, “Execution by cyanide gas is in essence ‘asphyxiation by suffocation or strangulation.’ [It] is extremely and unnecessarily painful.” He essentially urged California to join the growing number of states utilizing lethal injection.21

Lethal injection, while hailed by its advocates as the most humane method of carrying out executions, was also not without its problems. The killing chemicals had to be delivered intravenously, and finding suitable veins was an often-difficult process that required basic medical training. But doctors and other medical professionals felt constrained from participating in these tasks by the codes of their professions. Officials often depended upon less-skilled personnel, such as paramedics, and some executions were delayed or complicated by difficulties in locating, and connecting to, an appropriate vein.

There was controversy, too, over the chemicals used. The Chapman-Deutsch formula, concocted in Oklahoma, called for a three-step process: first, a barbiturate (sodium thiopental) to induce a coma; then a paralytic agent (pancuronium bromide) to paralyze the body's muscles and interrupt breathing; and, finally, a dose of potassium chloride, which stops the heart.22 Critics argue that we don't know for certain if the barbiturates produce a deep enough coma to prevent pain or sensation and that the use of pancuronium bromide as a paralytic is barbaric—its use is considered cruel by the American Veterinary Medical Association and is illegal for euthanizing animals in many of the states that use the same chemical for executions. But Dr. Jay Chapman, who developed the Chapman-Deutsch formula (still the most common formula in use), told us he is convinced the three-drug process is painless: “If the protocol is carried out properly, as it was set up, then there cannot be any possible issues of cruelty or unusual punishment or pain or suffering.”23

Lethal injection faced a major Supreme Court test in 2008. Two Kentucky inmates, Ralph Baze and Thomas Bowling, claimed that the mixture of chemicals designed by Chapman posed a risk of excruciating pain—cruel and unusual punishment—if improperly administered. Their pleas to die painlessly point out a principal irony, paradoxically also a strength, of our system: brutal murderers are allowed to litigate for mercies they didn't grant their victims. Baze killed two police officers who were attempting to serve a warrant; Bowling shot and wounded a two-year-old, then orphaned the child by killing his parents.

The case for Baze and Bowling was argued (pro bono) by Donald B. Verrilli Jr., a high-profile Washington lawyer later to become U.S. Solicitor General. In 2012, he would successfully argue the watershed “Obamacare” case before the Supreme Court.24

During Verrilli's oral argument against Kentucky's lethal drug mixture, the subjects of pain and constitutionality prompted a courtroom dialogue that found the justices reaching back for comparisons:

Justice Alito: Isn't your position that every form of execution that has ever been used in the United States, if it were to be used today, would violate the Eighth Amendment?

Verrilli: No.

Alito: Well, which form that's been used at some time in an execution would not violate?

Verrilli: We would have to suggest it to the test that we are advocating, which it would…whether there is a risk of torturous pain.

Justice Scalia: Hanging certainly would, right?

Verrilli: Well, it would have to be subjected to the test.

Scalia: Is that a hard question? Is that a hard question, whether hanging would, whether you had experts who understood the dropweight, you know, that was enough that it would break the neck?

Verrilli: If there is a risk of torturous pain and if there are readily available alternatives that could obviate the risk, then any significant risk—

Scalia: Hanging's no good. What about electrocution?

Verrilli: Well, it would depend. The argument about electrocution, Justice Scalia, is whether or not it is painless, and that was its point when it was enacted, that it would be a painless form of death.

Scalia: It has to be, it has to be painless?

Verrilli: It does not, but that was its point, and I think one would have to subject it to the test to see whether it inflicts severe pain that is readily avoidable by an alternative.

Alito: You have no doubt that the three drug protocol that Kentucky is using violates the Eighth Amendment, but you really cannot express a judgment about any of the other methods that has ever been used?

Verrilli: Well, electrocution may well. But it would depend again, Your Honor. If it could be established that it was painless, that there wasn't a risk that it could go wrong in a way that inflicts excruciating pain then it would be upheld…but that would be the test, the mode of analysis here, and I—

Scalia: I would think you'd have to show it's unusual, not painless. I mean, cruel and unusual is what we're talking about—there's no painless requirement in there.25

In the end, the Court upheld Kentucky's chemical protocol by a vote of 7–2. (This is the same case, as noted in Chapter 8, that saw Justice Stevens reverse course on capital punishment.) Said Chief Justice Roberts in the controlling opinion: “Because some risk of pain is inherent in even the most humane execution method, if only from the prospect of error in following the required procedure, the Constitution does not demand the avoidance of all risk of pain.”26

At this writing, Baze and Bowling still reside on Kentucky's death row. They have continued their fight against the three-drug system of lethal injection at the state level and could soon win the battle and lose their lives: Kentucky is considering following the lead of Ohio and Arizona in carrying out executions using one powerful sedative instead of the Chapman formula.

The search for the most efficient and “humane” method of execution, fine-tuning the process of death, continues.