I am innocent, innocent, innocent…. I am an innocent man, and something very wrong is taking place tonight.

—the last words of Leonel Torres Herrera, spoken at the Texas State Penitentiary at Huntsville at 4:35 a.m. on May 12, 1993

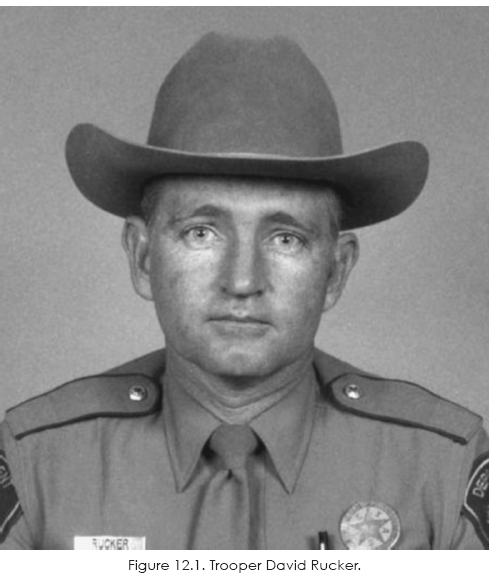

The last hour of Tuesday, September 29, 1981, was the last hour of Trooper David Rucker's life. The Texas Highway Patrol officer died shortly after 11:00 p.m.; his body was found on a stretch of rural highway east of Port Isabel and a few miles north of Brownsville. In the heart of the Rio Grande Valley, it was a dangerous neighborhood where drug trafficking was known to run rampant. Rucker, the father of three, was shot to death twenty-two days shy of his thirty-ninth birthday.

Only four minutes after Rucker's body was discovered, two police officers from the nearby town of Los Fresnos gave chase to a speeding car headed away from the place where the officer had been found. They pulled the car over and Officer Enrique Carrisalez approached the driver's side with a flashlight in hand. His partner, Enrique Hernandez, watched from the relative safety of their patrol car.

Hernandez saw the driver open the door and briefly exchange words with Carrisalez, and then he watched helplessly as the driver produced a gun and fired point-black at his partner. The car sped off; Carrisalez, hit in the chest, would die in the hospital nine days later.

A license-plate check revealed that the car belonged to the live-in girlfriend of Leonel Herrera, a thirty-four-year-old roofer. Hernandez identified Herrera as the shooter and, before he died, Carrisalez was shown a photograph of Herrera and nodded his head to confirm the identification. Herrera's Social Security card was found near Trooper Rucker's body, and blood of Rucker's type was later found on Herrera's jeans.

When Herrera was arrested a week after the shootings, he still had the keys to the murder car in his pocket, as well as a rambling, handwritten letter in which he implied that he had known Officer Rucker and had killed him in connection with a perceived grudge, presumably a drug deal gone bad.

The cold-blooded killing of two local police officers ignited the community. Herrera would be charged separately with each murder and face trial within four months for the death of Officer Carrisalez. Every day of the trial, Texas law-enforcement officers showed up in force in full dress uniform. Even one of the jurors was a Brownsville police detective, his firearm in full display for the remaining jurors to see. Three other jurors were seated who had told the court that friends or close relatives were police officers.1

The case against Herrera was strong. In addition to the letter tying Herrera to both murders, investigators found small quantities of blood on Herrera's wallet and in his girlfriend's vehicle that matched Rucker's type-A blood. Herrera acknowledged that he had access to the car that was used in both murders but said that his brother was using it that night. As for the Social Security card found near Rucker's body, Herrera said he always kept the card in the glove compartment of the car.2

While Herrera was in police custody and after he had invoked his right to counsel, an assistant district attorney walked into the interrogation room and asked Herrera why he had killed Officer Rucker. It was an improper inquiry for the DA to make. The law is clear that once a defendant requests an attorney, all questioning must cease. Herrera responded by jumping up and decking the attorney; he continued to beat the lawyer until forcibly restrained by police. The next morning, in a hospital room recovering from the incident, Herrera threatened to kill the police officers involved in his arrest upon his release. This did not help his case. He was convicted, and his attack on the assistant DA and threats to the police were introduced as evidence of Herrera's “future dangerousness” at the sentencing phase of his trial. Herrera was sentenced to death by lethal injection. Six months later, he pled guilty to Rucker's murder as well.

The case appeared to be open and shut—but Leonel Herrera would attempt to reopen it several times. He had an automatic right to review in the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, the state's highest court for criminal matters. There, lawyers challenged the way in which the two officers had identified him—in Carrisalez's case, from his deathbed and with just a single photograph. Despite the challenge, the conviction and death sentence were affirmed. Herrera then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which simply denied review, leaving the conviction and sentence intact.

In addition to direct appeals to the state's highest court and then the U.S. Supreme Court, a prison inmate can also challenge his conviction in both state and federal court if he can show that an aspect of his arrest or trial somehow violated the U.S. Constitution. The inmate submits what is called a petition for a writ of habeas corpus, the Latin words meaning essentially to “produce the body.” Access to post-conviction habeas corpus review has long been controversial in capital cases. Critics say it allows for interminable delay, but others say it is essential to prevent death sentences from being meted out through an unfair—and unconstitutional—arrest or trial. Herrera had filed a number of such petitions, all of which failed. A new execution date was set for December 17, 1990. Herrera then filed yet another petition in the state courts, which again failed but allowed Herrera to put off his execution for more than a year. The next execution date was set for February 19, 1992.

The Texas Resource Center, a federally funded organization that represents most of the state's death row inmates, was severely strapped and turned to an experienced death-penalty litigator in Florida for help. Mark Olive had more than a decade of experience in the field and had previously served as director of the Texas Resource Center's sister facility in Georgia. Olive had followed closely the efforts of the Reagan administration to sharply reduce the opportunities for death-row inmates to delay execution through what many regarded as frivolous and unnecessary habeas petitions.3

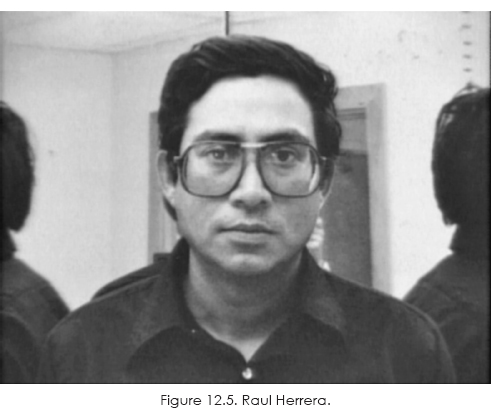

Three days before Herrera was to be executed, Olive came up with yet another habeas petition raising a new claim that took all the judges and prosecutors familiar with the case quite by surprise—that Herrera was actually innocent, that he did not commit the murders but that his younger brother, Raul, did.

Raul Herrera had died seven years earlier, shot to death by a former business partner who also may have been involved in the local drug trade.

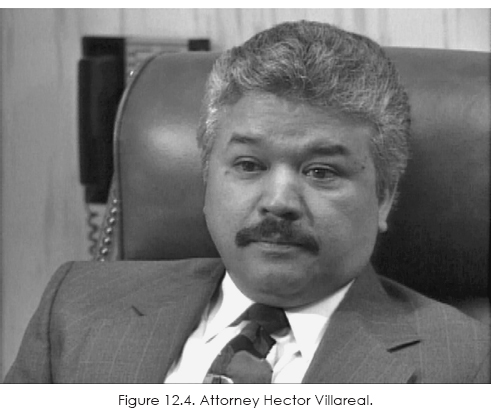

But Leonel now produced affidavits from Raul's onetime lawyer, a former state-court judge, asserting that Raul Herrera had told him that he, not Leonel, had shot and killed both Rucker and Carrisalez. The lawyer, Hector Villareal, told Olive (and subsequently the authors) that the Herrera brothers were both involved in a drug-trafficking operation with Officer Rucker.4

Two other men, one of them a former cellmate, also claimed that Raul Herrera had confessed to them how he had shot the officers. Raul's son also provided an affidavit swearing that he, although only nine years old at the time, had witnessed his father commit both murders. According to the son, he had been hiding in the car his father was driving. (This contradicted the trial testimony of Enrique Hernandez that the killer was alone in the vehicle.)

The state district court again denied the application, finding that “no evidence at trial remotely suggested that anyone other than [Leonel Herrera] had committed the offense.”5 Having exhausted the state-court system, Olive had one last shot—that is, to file again in federal district court. Federal district judge Ricardo Hinojosa was skeptical but also troubled by the prospect, however slim, of executing an innocent person. Citing “a sense of fairness and due process,” Hinojosa granted a stay so that Herrera's claim of actual innocence could be further considered. It would not be so simple.

Our criminal justice system leaves the determination of guilt to trial judges and juries. Whether the evidence was sufficient to support a conviction can be reviewed by a state's intermediate and supreme courts, and sometimes even by the U.S. Supreme Court. The standard for second-guessing a jury's verdict, however, is quite high. An appellate court does not sit as a thirteenth juror. It can only throw out a conviction on the grounds of insufficient evidence, should it conclude that “no rational trier of fact” could have found guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.6

Habeas review, however, does not ordinarily get into whether the defendant is guilty or innocent, only whether the arrest and trial were consistent with the guarantees of the Bill of Rights. Typical questions might include, for example, the following:

- Was the Fourth Amendment guarantee against unreasonable search and seizure violated?

- Was the Fifth Amendment guarantee against self-incrimination compromised?

- Did the defendant have the “effective assistance of counsel” guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment?

Herrera's lawyers argued that for the state to execute an individual who is innocent of the crime for which he was convicted and sentenced is itself a violation of the U.S. Constitution.7

It was now 8:30 in the evening and Herrera had been scheduled to be executed at dawn the following morning. The Texas Attorney General's Office immediately appealed Hinojosa's order to the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which, within a few hours, lifted the stay. Herrera's execution was back on. The three-judge panel stated its decision in stark, unambiguous terms: “The rule is well-established that claims of newly discovered evidence, casting doubt on the petitioner's guilt, are not cognizable in federal habeas corpus.”8 Herrera's guilt had already been settled by the trial Court and could not be reconsidered by the federal court no matter how compelling the new evidence of innocence might be. That, said the judges, was the law.

At 11:00 p.m., attorney Mark Olive took his appeal for a stay to the U.S. Supreme Court. At 1:30 a.m., the media reported that the stay had been denied. Olive called the clerk's office, which was still staffed to handle this case, to learn the vote and was told it was 5–4 with Justices Sandra Day O'Connor, David Souter, John Paul Stevens and Harry Blackmun indicating they would have granted the stay.

Here, Olive's understanding of the internal workings of the Supreme Court took on special value. He was aware that it took five justices—a majority—to grant the stay and that he didn't have five. But he was also aware that it took only four justices to grant review of a case—that is, to accept it and schedule it for oral argument. And he did appear to have four justices who felt his argument was sound enough to grant a stay. He told the clerk that he wanted to convert his application for a stay into what is called a petition for certiorari, essentially, a request that the Court exercise its discretion to take the case. Olive handwrote his changes and faxed the new petition to the Court. It worked, sort of.

Reflecting the sharp divide within the Court on the use of successive habeas petitions in death-penalty cases, the Court accepted the case for later review but still refused to grant a stay. It was the legal equivalent of half a loaf, peculiar to the Supreme Court and a practice the Court has considered abolishing. Without a stay, Herrera would be executed in a matter of hours and his case would become moot. Olive, however, was ready for this. He and his team of lawyers were already scouring the Texas judiciary to find a state-court judge who, when told that the Supreme Court had accepted the case, would grant the stay to keep the case, not to mention Olive's client, alive.

In Texas, the vast majority of judges run for election—which didn't make the task any easier. Eventually they found two judges who would grant the stay (neither of whom would agree to do so separately), and Herrera's execution would be put on hold at least until the U.S. Supreme Court decided his case. It would be one of the first cases the justices would take up when the Court opened its new term the following October.

The widow of Trooper Carrisalez spoke with the authors while the case was pending and she wept. “It just goes on and on and on. It just never ends.”9

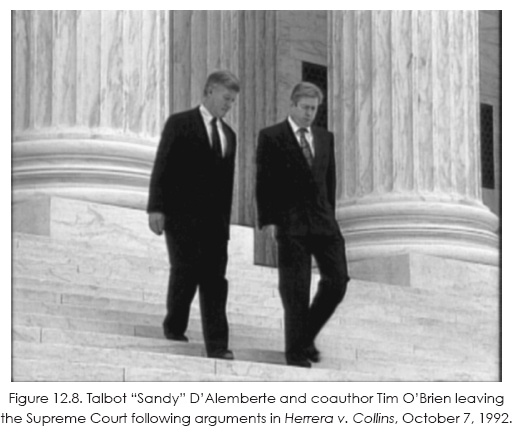

The risk of executing an innocent person has long been an important argument advanced by those who oppose capital punishment, and the leading anti-death-penalty groups pounced on the Herrera case. Given the split vote denying the stay, Olive was well aware that his high Court argument would be a challenge, and he wanted an attorney of exceptional stature to present it to the justices. He didn't have to look far.

Talbot “Sandy” D'Alemberte, halfway through his term as president of the American Bar Association, maintained an office two blocks away from Olive's and would be just such a choice. Olive knew D'Alemberte from the latter's days as dean of the law school at Florida State University, where they had worked together on death-penalty appeals almost twenty years earlier. D'Alemberte, who went on to become president of FSU, was also highly regarded in the legal community for both his intellect and his integrity.

D'Alemberte spent much of the summer of 1992 scrupulously preparing for his high Court argument, including making a visit to the Rio Grande Valley and his new client, Leonel Herrera. He believed in Herrera's innocence and in the valley's reputation for drug violence. More than ten years had passed since Officers Carrisalez and Rucker had been shot to death, but D'Alemberte said he could still feel the tension in the community. “It was a violent, violent place. I detected a widespread perception of corruption within the sheriff's office. I felt uncomfortable and out of place. It was just spooky.”10

After carefully studying the trial record, D'Alemberte felt that he might be able to pair Herrera's “colorable claim” of actual innocence with a constitutional violation. He initially believed that allowing a police officer to serve on the jury along with three other jurors who had close connections to law enforcement was so prejudicial that it might amount to ineffective assistance of counsel in violation of Sixth Amendment guarantees. After his visit, however, he concluded that having jurors who understood local law enforcement and its reputation for corruption might not have been such a bad strategy after all.

His argument in the Supreme Court got off to an inauspicious start.11 Justice O'Connor seemed to view the question presented—whether the state could execute an individual who is innocent—as an oxymoron. She asked D'Alemberte, “Now you don't really think that's the way the case comes to us, do you? He comes to us as a guilty defendant. He has been found guilty.” Herrera had been tried and convicted and sentenced. The conviction and sentence had been reviewed by the state's highest court. At least for this justice, that seemed to be the end of it. In the eyes of the law, Herrera was guilty.

D'Alemberte had anticipated the question and viewed getting the answer right as crucial. He had gone through a number of mock arguments with panels of distinguished lawyers in Florida, Georgia, and Washington, DC, in preparation for his argument in the Supreme Court. O'Connor's question was anticipated in each rehearsal. The answer D'Alemberte wanted to give was that Joan of Arc was also found guilty and burned at the stake at age nineteen for witchcraft and heresy. She's been considered one of the world's great martyrs ever since and was beatified by the Roman Catholic Church as a saint five hundred years later.

The panels D'Alemberte appeared before—which included some of the leading figures in the anti-death-penalty movement—didn't care for the reference. Leonel Herrera bore a striking non-resemblance to Joan of Arc, and some of D'Alemberte's mock inquisitors felt the analogy could rub some justices the wrong way. So D'Alemberte took their advice. “I recognized that many people had a great deal invested in this case and didn't want me screwing it up.”

Twenty years after the fact, he lamented not using the Joan of Arc comparison. The point was not at all that Herrera was like Saint Joan. The point was that if even a courageous heroine could be wrongly convicted, a saint, so can anybody; and federal courts should have the power to undo the damage.

D'Alemberte's advice to lawyers arguing big cases in the Supreme Court is that you do have to listen to those around you, “but in the end you have to decide for yourself what is right, what will work.”

Most states have strict time limits on the use of newly discovered evidence in petitions for a new trial. In Texas and a majority of states, a request for a new trial on the basis of newly discovered evidence must be submitted within thirty days of the conviction. The rationale is that there has to be some finality in court judgments, even death sentences, or the legal system would degenerate into chaos with each losing party seeking to reopen old cases.

But it wasn't just the thirty-day time limit that troubled D'Alemberte. Justice Byron White asked, “Would you be making this argument if Texas had a…say a 5-year time limit?” D'Alemberte responded, “Yes, sir. Your Honor, I believe that innocence is a value which trumps all other time limits.”

Justice O'Connor pressed D'Alemberte to state precisely the rule he would have the Court adopt. D'Alemberte answered: “The rule that we would suggest is the rule that says that an inmate with a colorable claim of innocence may not be executed without provision for a hearing, due process to determine the merits of that claim—”

Justice Anthony Kennedy interrupted, “And if they commuted his sentence to life, then that would be the end of the case?” D'Alemberte: “That would be the end of this case, Your Honor…. I don't—”

Justice Antonin Scalia, who clearly was not persuaded, saw an opening. “That's not cruel and unusual? That's not cruel and unusual to leave him in prison for life although he has a colorable [claim of innocence].”

D'Alemberte replied that he didn't know how far the Eighth Amendment would go to protect a convicted person who had a “colorable claim” of innocence but that it at least must go far enough to prevent his execution. The prospect of countless new hearings to reconsider guilt and D'Alemberte's inability to articulate any limiting principle to the rule he sought weighed heavily on Scalia. “I think one has to consider how much damage we do to the system of criminal justice if we apply it across the board to all prisoners, no matter how much after the fact they choose to bring in new evidence raising a colorable claim of innocence. The witnesses from the prior trial are dead or gone. The burden this would put upon a system of justice is enormous.”

Scalia was moving in for the kill. He got D'Alemberte to acknowledge that no state required the kind of new hearing to determine guilt that he, D'Alemberte, claimed the Constitution required and that such post-conviction hearings were unheard of in Anglo-Saxon common law. “What basis do you have for it other than your intuition?” D'Alemberte responded: “Your Honor, when I read the phrases used by this Court referring to miscarriages of justice and I began to put in my mind what is the greatest possible miscarriage of justice, it occurs to me that the greatest one that I could formulate would be the execution of an innocent person or the execution of a person who had a colorable claim of innocence. You would not want that person to be executed without hearing that case.”

Justice Kennedy was similarly skeptical: “So, in other words, you have two shots at the judicial system? You can elect a strategy that fails and then because you're really innocent, you can start all over again? You can double deal the judicial system in that way just because death is at issue?” D'Alemberte again: “And because innocence is a paramount value, yes, Your Honor.”

In one respect, the Court may have been between the proverbial rock and hard place. What if an individual convicted of a murder in the course of a robbery and sentenced to death could actually demonstrate that he was an astronaut on the moon at the time of the crime? Would Texas still be allowed to go through with the execution? It is a highly unrealistic hypothetical, but what if? The thought had occurred to Justice Kennedy, who asked Margaret Griffey, the assistant attorney general representing Texas, “Suppose you have a video tape which conclusively shows the person is innocent, and you have a state which as a matter of policy or law, or both, simply does not hear new evidence claims in its clemency proceeding. Is there a federal constitutional violation in your view?”

Griffey: “No, Your Honor, there is not.” It turned out some justices agreed with Griffey, but not all.

|

For a video report on the Herrera Supreme Court case, go to: http://murderatthesupremecourt.com/herrera |

The Court announced its decision on January 25,12 a relatively short turnaround for such an important case. It rejected Herrera's arguments. Chief Justice William Rehnquist, writing for a six-justice majority, said that absent some claim of a federal constitutional violation, the federal courts simply did not have the authority to even consider Herrera's “free-standing claim” of actual innocence. The court noted that the trial is the “paramount event for determining the defendant's guilt or innocence” and that Herrera's claims had to be evaluated “in light of the previous ten years of proceedings in this case…. Where, as here, a defendant has been afforded a fair trial and convicted of the offense for which he was charged, the constitutional presumption of innocence disappears.”

Justice Blackmun wrote a passionate dissent that was joined by Justices Stevens and Souter. Blackmun concluded, “Just as an execution without adequate safeguards is unacceptable, so too is an execution when the condemned prisoner can prove that he is innocent. The execution of a person who can show that he is innocent comes perilously close to simple murder.”13

The decision did leave Herrera an out. He could petition then governor Ann Richards for clemency; however, clemency was generally considered an empty remedy in Texas, which, since the Supreme Court reinstated capital punishment in 1976, had been putting more inmates to death than any other state. During the oral argument in the case, counsel for Texas acknowledged there had not been a death-penalty commutation in the state in the past fifteen to eighteen years. In Texas, executive clemency requires a recommendation from the Board of Pardons and Appeals and then action by the governor. Leonel Herrera received no clemency; he was executed by lethal injection on May 12, 1993.

|

To see a preview of the Supreme Court's arguments in the Herrera case, go to: http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/video/tim-obrien-herrera-collins-17067566 |

The case produced six different opinions, and while the result for Herrera was clear—the state of Texas could proceed with his execution—the collection of opinions did not clearly answer the question Justice Kennedy had posed during oral argument regarding the plainly innocent inmate.

Justice White, in a separate concurring opinion, suggested a federal habeas court could stop an execution if it found that “no reasonable trier of fact” would have found the defendant guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. But no other justice joined White's opinion. Chief Justice Rehnquist, in his opinion for the Court, wrote that if the Court were to assume for the sake of argument that a posttrial demonstration of actual innocence would render an execution unconstitutional, Herrera's innocence claims fell far short. Rehnquist concluded that the threshold of proof “would necessarily be extraordinarily high because of the very disruptive effect that entertaining such claims would have on the need for finality in capital cases, and the enormous burden that having to retry cases based on often stale evidence would place on the states.”14

Justice Scalia wrote separately to ridicule the dissenting justices. “If the system that has been in place for 200 years ‘shocks’ the dissenters’ consciences, perhaps they should doubt the calibration of their consciences, or, better still, the usefulness of ‘conscience shocking’ as a legal test.” Scalia concluded, “With any luck, we shall avoid ever having to face this embarrassing question again, since it is improbable that evidence of innocence as convincing as today's opinion requires would fail to produce an executive pardon.”15

The decision, however, did little to dilute the long-standing concerns about the risk of error that some see as inherent in capital punishment. It continues to be one of the leading arguments advanced by opponents. Nor did the Herrera decision spare the Court from “ever having to face this embarrassing question again,” as Justice Scalia had hoped. In fact, one of the side effects of the Herrera case may have been to demonstrate the effectiveness, if not the necessity, of adding an actual innocence claim in any federal death-penalty appeal. For one, Congress amended the federal habeas statute to prohibit federal courts from considering a second, or successive, petition from death-row inmates absent a plausible claim of innocence.16 A plausible claim of innocence, and even one not so plausible, can also draw a faithful following in support of a lesser sentence.

The case of O'Dell v. Netherland,17 which reached the Supreme Court in the fall of 1996, is illustrative.18 Forty-four-year-old Helen Schartner left the County Line Lounge in Virginia Beach at about 11:30 p.m. on February 5, 1985. Joseph O'Dell left the same club a few minutes later. The following day, Schartner's body was discovered in a muddy area across the highway from the nightclub. Tire tracks that matched the tires on O'Dell's car were discovered near Schartner's body.

Schartner had been strangled. She also had been pistol whipped, sustaining eight blows to the head, which had produced extensive bleeding. A handgun had been seen in O'Dell's car about ten days prior to the murder.

A few hours after leaving the County Line Lounge, O'Dell showed up at a convenience store with blood on his face and hands, in his hair, and down the front of his clothes. Later in the morning, he turned up at the home of a former girlfriend, Connie Craig, explaining that he had vomited blood all over his clothes and wanted her help in cleaning them up. Craig, however, had read about the murder at the County Line Lounge in the newspapers, knew that the lounge was a favorite watering hole of O'Dell, and called the police a few days later.

O'Dell explained to police that the blood on his clothing was the result of being struck in the nose while trying to stop a fight at another club the previous evening.

Forensic evidence established that the dried blood on O'Dell's shirt and jacket was the same type as Schartner's. (O'Dell's blood type was not the same as Schartner's, thus proving that it could not have been his own.) O'Dell's car was later seized, and dried blood found on objects in the car also had several enzyme markers consistent with Schartner's blood, but not O'Dell's. Vaginal and anal swabs disclosed the presence of seminal fluid in the victim's vagina and anus containing enzymes consistent with those in O'Dell's seminal fluid. A fellow jailhouse inmate, Steven Watson, testified that O'Dell admitted strangling Schartner after she refused to have sex with him.

At the time of Helen Schartner's death, O'Dell was on parole for kidnapping a convenience-store clerk at gunpoint. He had threatened to rape and kill her. He had spent much of his adult life in prison, where he had killed another inmate.19 At the sentencing phase of O'Dell's trial for Schartner's murder, the jury learned of his troubled past and cited O'Dell's “future dangerousness” as an aggravating circumstance that would justify his death sentence.

At the time of his trial in 1986, DNA testing was still in its infancy and the blood-matching methods in use at the time were not nearly as reliable as what would soon become available. Given his consistent claims of innocence, DNA testing was permitted on O'Dell's clothing four years after the conviction, in 1990. It turned out that the blood on O'Dells shirt—contrary to what the jury was told at the trial—did not match either the victim or O'Dell. Although the DNA tests showed that numerous bloodstains on O'Dell's jacket did match that of the victim, O'Dell and his lawyers claimed the misidentified blood on his shirt exonerated him. The state of Virginia, they claimed, was about to execute an innocent man.

There was another, more persuasive issue surrounding O'Dell's death sentence. Eight years after O'Dell's trial, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Simmons v. South Carolina20 that whenever “future dangerousness” is offered as an aggravating circumstance in support of a death sentence, the jury must be told if the defendant would be forever ineligible for parole if given a life sentence. Lawyers for O'Dell had asked for just such an instruction from the judge in his case, but the request had been denied. The jury was never told that if it returned a verdict of less than death, O'Dell would never be released from prison. The somewhat technical—but nonetheless crucial—question for the U.S. Supreme Court was whether its decision in the Simmons case should be applied retroactively to hundreds of other inmates sentenced to death by juries that had never received the instruction the Supreme Court now ruled was required by the U.S. Constitution.21

It was, however, the more inflammatory question of whether the United States could execute a man who had a plausible claim that he was wrongly convicted that caught fire. That was the way O'Dell supporters framed the issue, even though the trial judge and thirteen Virginia appeals-court judges concluded that O'Dell was guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, notwithstanding the misidentified blood sample from his shirt.

It may have started when O'Dell created his own Internet website to promote his case. Amnesty International, which opposes the death penalty in all cases, also took on a leading role in publicizing the innocence issue. It became a cause célèbre in Italy. The Vatican got involved, with Pope John Paul II sending personal letters to Virginia governor George Allen and President Bill Clinton urging clemency. Top Italian politicians followed, with President Oscar Luigi Scalfano and Prime Minister Romano Prodi speaking out on behalf of O'Dell. So did Mother Teresa, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize. Sister Helen Prejean wrote critically about the O'Dell case in her books Death of Innocents22 and Dead Man Walking,23 the latter of which formed the basis for the highly acclaimed motion picture of the same name.

Did any of this help? Probably not; although the Court did agree to hear O'Dell's appeal. When justices deny review to a case, it is not unusual for a justice to issue a dissent explaining why he or she thought the case should have been accepted. In the O'Dell case, Justice Scalia took the most unusual—to the authors, unheard-of—step of issuing a statement criticizing, and clarifying, the grant of review.24 Scalia pointed out that the Court agreed to review only the question about the retroactivity of Simmons v. South Carolina and that the Court specifically did not intend to consider O'Dell's claim of actual innocence. Scalia is a devout Roman Catholic, and some Court insiders viewed his unusual opinion as, at least in effect if not in intent, a personal letter to the pope. Scalia would subsequently give a talk arguing that the question of capital punishment is not one on which the pope's word is decisive for Catholics.25

|

For a video report on the O'Dell Supreme Court case, go to: http://murderatthesupremecourt.com/odell |

Six months later, the Court issued its decision finding that the Simmons decision should not be applied retroactively, setting the stage for O'Dell's execution.26 His last day alive was July 23, 1997. It was a day of vivid contrasts at the Greensville Correctional Center, just outside Jarratt, Virginia.

Shortly after noon, O'Dell was married to a Boston law student, Lori Urs, whom he had met through Sister Prejean's ministry. The ceremony was conducted through the bars of O'Dell's cell in the prison's L Unit, just steps from the execution chamber. The bride had been strip-searched on entering the unit; she and O'Dell were not allowed to touch during the ceremony. The rings were exchanged by proxy: Sister Prejean for the bride, a chaplain for the groom.27

Joseph O'Dell was put to death by lethal injection at 9:16 p.m., after the Supreme Court rejected a last-minute appeal. Lori Urs O'Dell, married for less than ten hours, was now a widow. The Court simply did not find O'Dell's claim of actual innocence convincing, just as it was not persuaded by Leonel Herrara's claim. In the Herrera case, however, as we'll see shortly, the Court did seem to leave the door open for reconsideration in a truly compelling case. In fact, actual innocence is an issue that is all but certain to dog the Court in years to come.

The U.S. criminal-justice system has entered an age where proof equivalent to being on the moon at the time of the crime is not completely unrealistic. While Herrera's claims were based on affidavits, legal instruments that for all of their weaknesses have an acknowledged place in the legal system, future cases will involve new forensic findings and technologies that are reshaping—and in some cases, redefining—criminal prosecution.

The “gold standard” of scientific evidence in the courtroom—as well as on Law & Order, CSI, and its television forebears—used to be fingerprint identification. No more. The courts have held that fingerprint comparison has components of art as well as science. Stephan Cowans spent seven years in a Massachusetts prison for the shooting of a Boston police officer, convicted primarily on the testimony of a fingerprint examiner who “matched” his print to one at a crime scene. The later testing of DNA strands, the genetic blueprints unique to individuals, proved the examiner wrong and proved Cowans's innocence.28

Hair and fiber comparisons are also subjective. In July of 2012, the Justice Department began a review of thousands of cases, going back to at least 1985, where convictions were obtained because of possibly flawed forensic examinations conducted by the prestigious FBI Laboratory.29

Arson evidence also relies heavily on interpretation. Cameron Willingham was executed in Texas in 2004 for the arson murders of his three young daughters. Months after his execution, five independent experts issued a report questioning the validity of the arson evidence and forensic testimony used to convict Willingham. Texas authorities have begun a reexamination of the state's forensic procedures.30

The reviews of the Cowans and Willingham cases were prompted by the Innocence Project, which has overturned almost three hundred felony convictions by uncovering new evidence and discrediting old evidence, primarily through DNA testing—the new “platinum standard” of forensic evidence.

The Innocence Project was born at Yeshiva University's Cardozo School of Law in 1992, the brainchild of faculty members Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld. Now an independent nonprofit, although closely affiliated with Cardozo, it seeks to overturn wrongful convictions and to reform the criminal justice system.31

Since 1993, with the advent of DNA testing, and primarily through the work of the Innocence Project, seventeen condemned prisoners have been exonerated. Exonerated—as in, their convictions were not overturned because of a procedural error or legal technicality; instead, scientific evidence demonstrated conclusively that the accused had not committed the crimes for which they had been convicted. Although innocent of those crimes, they had been condemned to death.

Those seventeen condemned inmates had been convicted in eleven states and served a total of 187 years on death row. For one of them, exoneration came too late: Frank Lee Smith died in a Florida prison of cancer in January 2000 after serving fourteen years on Florida's death row. DNA evidence subsequently showed he could not have committed the crime.32

|

To view a PBS Frontline documentary on the Frank Smith case, go to: http://murderatthesupremecourt.com/smith |

Frank Smith escaped the executioner because of a terminal disease; but for DNA testing, some or all of the sixteen other exonerated prisoners could well have been put to death.

Some proponents of capital punishment say, “So what?” They argue that, while mistakes were made in a limited number of cases, the system generally works. They challenge the opposition to identify a single case where a clearly innocent person has ever been executed.

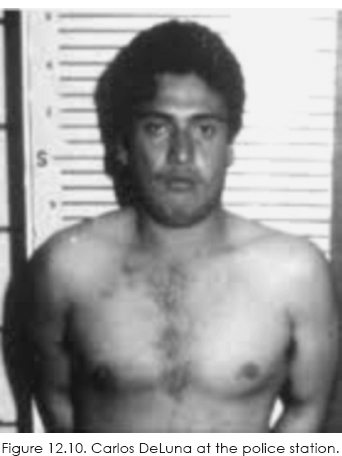

That is difficult to do, but new evidence indicates that the Texas execution of Carlos DeLuna in 1989 may well be that case.33

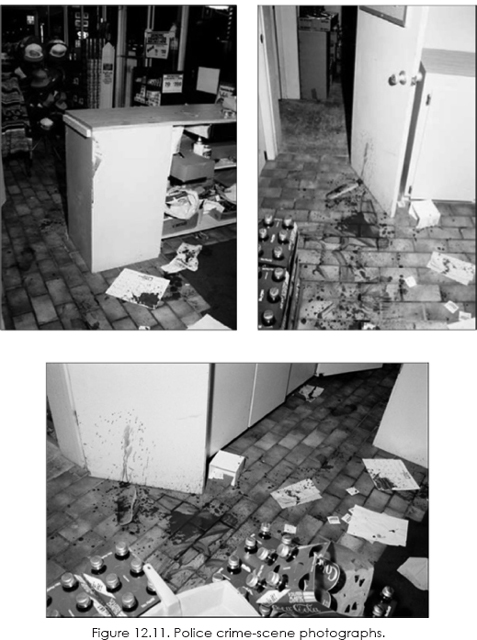

DeLuna was convicted of the stabbing murder of Wanda Lopez, a twenty-four-year-old single mother who was tending the cash register at a gas station and convenience store. A chilling 9-1-1 recording begins with Lopez reporting a man with a knife threatening her, and it ends with Lopez pleading for her life. “Please!” she screams…and the phone goes silent.

A customer pumping gas outside, Kevan Baker, saw a scuffle and ran toward the door, briefly establishing what he called “eye-to-eye contact” with the fleeing attacker. Lopez slipped into unconsciousness as Baker reached her.

Forty minutes later, police arrested Carlos DeLuna, then twenty years old, after dragging him, drunk and disoriented, from under a pickup truck found several blocks away from the gas station. He matched several elements of descriptions provided by Baker and two other witnesses who saw a Hispanic man near the gas station. DeLuna had been arrested many times previously for public drunkenness; he had also served prison time for attempted rape and car theft. Police hustled him to a squad car and drove back to the gas station.

Researchers from Columbia University's law school have put together an exhaustive study of events following Wanda Lopez's death on the night of February 4, 1983. Under the direction of Professor James S. Liebman, they reconstructed the sequence of events by combing all the law-enforcement files in the case and directly reinterviewing the participants. The book-length report, titled Los Tocayos Carlos, was published in the Columbia Human Rights Law Review in the spring of 2012. Details of the case discussed here can be found in full in that report.

Kevan Baker recalled the night vividly when he talked with a private investigator connected with the Columbia project. He was at the gas station when officers arrived with a suspect in the backseat of their car. “Is this the guy you seen?” a police lieutenant had asked him. “Yeah, that's the guy,” Baker had said. Later, at the station house, two other witnesses identified DeLuna's picture from a photo array. DeLuna was booked for capital murder.

“It was really tough,” Baker told the Columbia investigator, but “it seemed like the right guy.” It was also tough identifying DeLuna in court, Baker said, looking back, “But it just seemed right.” His voice trailed off as he added, “Whether I was right or wrong…”

George Aguirre, another gas-station customer, also identified DeLuna as he sat in the squad car. But when he testified at DeLuna's trial, he balked: “I'm not too sure.”

There was no forensic evidence introduced at the trial that linked DeLuna to the victim or the crime scene. No blood traces were found, either on his body or on the clothing police recovered near the location of his arrest. This, despite widespread patterns of pooled and spattered blood near Lopez's body.

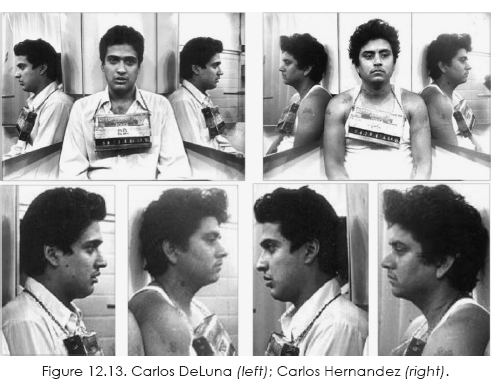

At his trial, DeLuna testified that he had been on the street near Lopez's gas station, and that he had seen another man he knew, Carlos Hernandez, inside the gas station wrestling with a woman. Asked why he left, DeLuna said, “I know I got a record…I just kept running because I was scared, you know?”

Members of the jury may have reacted the same way Wanda's cousin, Becky Nesbitt, did as she heard DeLuna testify: “When Carlos DeLuna said that he did not do it, that it was another Carlos, when I heard that at the trial I thought, that's just a lie.”

The jury deliberated for four hours, and during their deliberations the prosecutor offered to take the death penalty off the table in exchange for a guilty plea. DeLuna refused, proclaiming his innocence. When the jury returned to the courtroom, the verdict was read aloud: “The defendant, Carlos DeLuna, is guilty of capital murder as alleged in the indictment.” And after a sentencing hearing, the same jury condemned him to death.

Judge Wallace Moore would later set the jury's verdict into motion with this formal, stark order:

CARLOS DE LUNA…shall before the hour of sunrise on Wednesday, the 15th day of October A.D., 1986 at the state penitentiary at Huntsville, Texas, be caused to die by intravenous injection of a substance or substances in a lethal quantity sufficient to cause death into the body of the said Carlos De Luna.

The date was delayed several times by appeals, but the order of the court was finally carried out at 12:14 a.m. on December 7, 1989. The apparent truth of Carlos DeLuna's innocence surfaced only later.

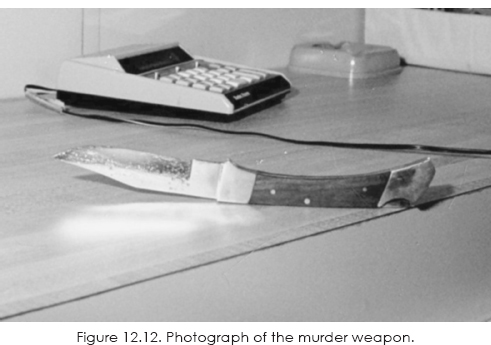

The man DeLuna had accused of the crime, Carlos Hernandez, confessed to several relatives and friends that he murdered Wanda Lopez. The investigators from the Columbia Law School research project documented and cross-checked those confessions meticulously; the details of each account held up. The wooden-handled, seven-inch buck knife that was recovered at the crime scene was identified by a score of Hernandez's associates, friends, and relatives, as well as by police officers who had previously arrested him, as the type of knife he habitually carried. Despite dozens of arrests, DeLuna was never known to carry or use a knife or a weapon of any kind. A careful review of the witnesses’ descriptions of the sloppily dressed, mustachioed man they saw reveals that their descriptions do not match DeLuna, who was clean-shaven and in dress clothes when he was arrested nearby. His clothes didn't have a speck of blood on them, despite the blood-drenched crime scene. The witnesses’ descriptions matched Hernandez's characteristic dress and grooming to a T.

The law school investigators used a photograph of the murder weapon; the original weapon was lost or misplaced after the trial, along with all of the physical evidence in the case, by the District Attorney's Office. But even Hernandez's own lawyer, Jon Kelly, had no doubt about the knife in the photograph: “Yes. He (Hernandez) had that on him all the time,” he said. There was no way to conduct scientific tests on the knife, of course—the evidence had vanished.

Carlos DeLuna was convicted largely on the basis of the testimony of a single eyewitness to the crime. But any confusion by witnesses was understandable: relatives of both men described them as “tocayos”—twins. They were the same weight and height and looked very much alike. When investigators showed a picture of DeLuna to Hernandez's brother-in-law, Fernando Schilling, he first identified it as Hernandez. Told of his mistake, he said, “Man, he's a ringer [for] Carlos Hernandez. That gives me the goose bumps.”

Hernandez was both amoral and brutal. Throughout his life, he had raped and abused children, including his nine-year-old niece and younger brother. He had an extensive felony record, including prison terms for gas-station armed robberies and assault with a deadly weapon (a knife). He was found guilty of negligent homicide in an automobile death, and he narrowly escaped a murder conviction in the knifing death of a girlfriend. He was, his friends said, “a really mean guy” and “a badass.” A police officer was even more direct, calling him a “mean motherfucker.”

Hernandez would eventually die in prison of cirrhosis of the liver. He was serving a sentence for assault—his thirteenth arrest while carrying a knife. His mother refused to claim the body, allowing her son to be buried in a pauper's grave. “Dirt is dirt,” she said.

The mistakes made in the prosecution of Carlos DeLuna are beyond remedy. The flaws in the evidence and the sloppiness by police and prosecutors, combined with lackluster defense, worked to send him to the death chamber. The eyewitness testimony against him turned out to be incorrect. The careful documentation of the Columbia investigation lead to the inescapable conclusion that the wrong man was put to death for Wanda Lopez's murder.

The claim of Carlos DeLuna's innocence was not asserted before his death and, accordingly, never reached the Supreme Court. But the case of Leonel Herrara will almost certainly not be the last to be considered by the Court on the grounds of “absolute innocence.”

The Supreme Court will inevitably deal with that claim again, in the context of new and emerging technologies. However, the Court will not rush to either consideration or judgment; the institution is traditionally deliberate. It is no architectural accident that stone turtles are found in numerous locations around the iconic Supreme Court building, supporting lampposts at the entrances and exit at the ground level, and on one of the corners on the Second Street side. Justice Scalia once remarked in an interview, “Yes, we're slow, just like the turtle. But when was the last time you saw a turtle trip?”34

Both sides in the landmark Herrera case left the door open for future consideration. Justice Blackmun, voicing disappointment as he dissented, wrote, “I believe it contrary to any standard of decency to execute someone who is actually innocent…. I also believe that [a] petitioner may raise an Eighth Amendment challenge to his punishment on the ground that he is actually innocent.”35

Supporting the majority, Justice O'Connor was nevertheless clear about the limitations of the Herrera ruling and about its implications: “The Court has no reason to pass on, and appropriately reserves, the question whether federal courts may entertain convincing claims of actual innocence. That difficult question remains open.”36