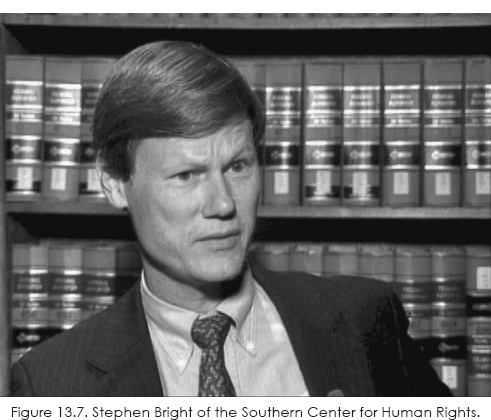

So long as juries and judges are deprived of crucial information and the Bill of Rights is ignored…the death penalty will continue to be imposed, not upon those who commit the worst crimes, but upon those who have the misfortune to be assigned the worst lawyers.

—Stephen Bright, president and senior counsel for the Southern Center for Human Rights, in the Yale Law Journal 103 (1994)

Assume the following: You don't have a lot of money. You've led an exemplary life. But for one reason or another, you're wrongfully charged with a heinous crime. You're on trial for your life, and your lawyer shows up drunk or falls asleep, snoring loudly as the prosecution makes out its case against you. Assume for a moment you're a poor black man in Georgia and your lawyer turns out to be the former imperial wizard of the state Ku Klux Klan, who refers to you as a “nigger” in open court. Far fetched? Not at all. All of the above have occurred and, in each case, resulted in a death sentence. It is scandalous and it continues today.1

The Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees all criminal defendants the effective assistance of counsel. Most of the defendants whose crimes have been recounted in this book have had good lawyers representing them at trial, some have even had outstanding lawyers arguing their appeals. Many capital defendants do get the kind of representation the Constitution requires. Alas, far too many do not. This chapter borrows heavily from the groundbreaking work of Stephen Bright and the Southern Center for Human Rights, which has taken a leading national role in promoting fairness and due process of law to those least able to afford adequate legal representation. The authors acknowledge their deep debt.

As discussed below, some of the nation's most prominent jurists and lawyers have recognized the problem of inadequate representation to poor people generally, and especially to those who are on trial for their lives, but little has been accomplished to remedy the problem. The Supreme Court has reviewed a number of cases involving standards for gauging the level of competency required of counsel in capital cases. The justices have had a wide range of opportunities to clarify the issue. The line between what is acceptable and what is not when a defendant's life is on the line, however, remains murky.

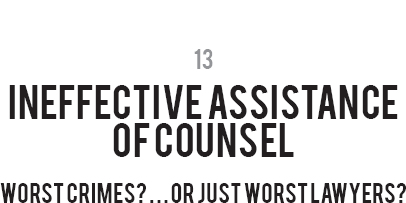

The case of George McFarland would seem to have presented an easy test.2 McFarland was charged with capital murder arising out of the armed robbery of a grocery store in Houston, Texas. Kenneth Kwan had run the C&Y Food Center in Houston's low-income Trinity Gardens neighborhood for seventeen years. He knew that on Fridays, many customers would cash their payroll checks at his store. His routine was to go to the bank on Friday mornings accompanied by a security guard, James Powell, and withdraw enough cash to cover all the checks. Powell would carry a shotgun. On this particular Friday, November 15, 1991, they arrived back at the store to find two armed, young black men waiting for them.

As Kwan and Powell got out of their van, one of the men approached the security guard, pulled out a handgun, held it to the guard's head, and threatened, “Drop the gun. Drop the gun. If you don't, I'll blow your goddamned brains out.” Powell said he complied but then heard a series of shots—“pop, pop”—fired at Kwan, who had rushed toward the store door. The two men ran off with $27,000 in cash, leaving Kwan bleeding to death on the sidewalk.

McFarland was arrested after his twenty-year-old nephew, Craig Burks, called Crime Stoppers to report that McFarland had boasted of holding up a grocery store and had displayed large quantities of cash. Crime Stoppers had paid Burks $900 for the tip; it turns out that Burks was also offered a reduced sentence on a separate aggravated robbery charge in return for his testimony.

The only other evidence against McFarland was from an eyewitness, Carolyn Bartie, who was sitting in her car outside the store about to buy some stamps when the shooting unfolded. She told detectives at the time that everything had happened so fast, she did not think she could identify either of the assailants. A month later, however, Bartie, who worked for the Houston Police Department in a secretarial capacity, tentatively identified McFarland as the shooter from a display of photos of six individuals. She subsequently picked him out at a lineup and identified him at trial. The security guard, James Powell, also testified at McFarland's trial. Asked if he saw the man who shot Kwan seated in the courtroom, Powell responded “No, I do not.” Enough to create a reasonable doubt?

There was no forensic evidence connecting McFarland with the murder. No fingerprints. No murder weapon. Bartie initially told police that the man who shot Kwan was about five feet eight inches tall and weighed about 150 pounds. McFarland is six feet one and weighs over 200 pounds. He has consistently maintained his innocence.

Texas has no public-defender system for capital cases, and the court-appointed lawyers in Harris County had a reputation for moving capital cases through the system swiftly. Some of the lawyers favored by judges (but heavily criticized by the local bar) would be handling a dozen capital cases at the same time. Aware of this, McFarland scraped up all his money to hire his own attorney.

The idea was sound, but the selection of seventy-two-year-old John Benn turned out to be a fatally bad choice. Benn had forty-two years of trial experience but hadn't tried a capital case in the last twenty. He'd been around the block a few times, perhaps a few times too many. The trial judge, Doug Shaver, said later, “I knew John Benn. I knew he wasn't competent.” Shaver said Benn had the appearance of a heavy drinker. “His clothes looked like he slept in them. He was very red-faced; he had protruding veins in his nose and watery red eyes…. I can't imagine anyone hiring him for a serious case.”3

Benn spent only about four hours preparing for the trial. He failed to interview any of the witnesses. He prepared no motions and sought no subpoenas. Instead, he relied exclusively on what was in the prosecutor's file. He never went to the crime scene. He visited McFarland only twice prior to the trial.4

If the pretrial work was lacking (and it clearly was), the performance at the actual trial was even worse.

Benn slept through critical portions, including jury selection, at the very start of the trial, and at the end during the penalty phase. It was not just an occasional doze. The sleep was often accompanied by loud snoring. Benn did not deny it. At a posttrial hearing, Benn explained, “I customarily take a short nap in the afternoon.” In an interview with the authors, Benn said he found the penalty phase of the trial “boring.” We reminded Benn that this was the part of the trial when the jury would decide whether McFarland would live or die, that it wouldn't be boring for his client. Benn conceded, “No, it would not.” McFarland's life was on the line. “Yes, it was.”5

Speaking from death row at the Polunsky Correctional Center in West Livingston, Texas, McFarland told us that he was furious with his lawyer but didn't know how to show it, fearing the impact any visible display of anger might have on the jury. “He slept so hard,” said McFarland, “I stuck my foot up on his chair and nudged him, and he jumped.”6

The local papers carried stories about how Benn, on one of the last days of the trial, fell asleep in his chair, “head rolled back on his shoulders, his mouth agape.”7 Aware that Benn was not quite up to the task, Judge Shaver appointed another lawyer, Sandy Melamed, to assist Benn. Melamed, however, had never handled a death-penalty case. He says he had little communication with Benn before or during the trial other than to establish that Benn would be the lead attorney and would be making the critical decisions on trial strategy. Melamed later told the Houston Chronicle, “I think the poor old guy was tired at the end of the day. Being at trial for 10 or 12 days in a row, I think it wore him out.”8 Judge Shaver later allowed in his interview with us, “It's not the kind of defense I would want if I were on trial for my life.”9

Could this, by any standard, have been a fair trial? The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, dividing 7–2, concluded that it was. The Court noted that McFarland did have two attorneys, the one who was asleep (Benn) and the one who had no death-penalty experience (Melamed). The court's majority opinion pointed out that Melamed himself had said Benn's dozing off could have had the effect of winning the sympathy of the jury, a strategy the court found plausible.10

Judge Charlie Baird wrote a sharp dissent:

I find the majority's suggestion that it was somehow reasonable trial strategy for appellant's lead counsel to take a “short nap” during trial utterly ridiculous. The possibility of jury sympathy can never be a reasonable alternative to effective representation. A sleeping counsel is unprepared to present evidence, to cross-examine witnesses, and to present any coordinated effort to evaluate evidence and present a defense. In my view, a sleeping attorney is no attorney at all.11

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals is the state's highest court for criminal cases, and its decisions can be appealed directly to the U.S. Supreme Court. McFarland's new attorneys did appeal to the Supreme Court, but on November 29, 1993, the justices announced that they would not hear the case.12

Denial of review means the lower-court decision stands, but with neither approval nor disapproval from the nation's highest Court. The denial of review sets no binding precedent on other courts.

Curiously, the identical sleeping-lawyer issue came back to the U.S. Supreme Court almost ten years later, except that in this case, the lower court had ordered a new trial, finding the defendant's right to the effective assistance of counsel had been violated. The justices again, without comment, denied review, allowing that contrary decision to stand.13

The justices do try to resolve conflicts among the courts, especially when they arise out of different federal circuits on questions of federal law. But it takes the consent of at least four of the nine justices for a case to win review, and there can be some strong and little-understood reasons for voting not to review a case. The Supreme Court regularly takes up the most divisive questions facing our society, and it should come as no surprise that the Court itself is often sharply divided on some of these issues. The justices get along remarkably well, having recognized that serious disagreement goes with the job and that the weight of opposing viewpoints needs be taken into consideration when granting review to a case. A case may be denied review not because the justices believe it was correctly decided at the lower court level, but rather because they believe it was wrongly decided and it could only become worse—thereby setting a national precedent—should a majority of the Court vote to affirm. We do not know why, however, the Court declined to review these two sleeping-lawyer cases and pass up the opportunity to provide much-needed guidance to the states on the level of competence required of attorneys in capital cases. The justices rarely explain why they deny review, and they didn't in these cases.

At last report, McFarland was still on death row more than twenty years after the offense. He still has motions challenging the fairness of his trial pending before a federal judge in Houston. He is still angry about the representation he received. His attorney falling asleep, however, isn't what bothers him most. What he says bothers him most is that he spent the last twenty years of his life incarcerated for a crime he insists he did not commit.14 No other suspect has been arrested.

McFarland had spent much of his life in trouble. He had a long arrest record. And as prosecutors had argued in the penalty phase of his trial, he may well have posed a continuing threat to society. He may be guilty as charged. Those to whom we entrust the power to enforce the rules, however, must also play by the rules. No matter how guilty the accused may appear to be—or may in fact be—the trial must be fair and appear to be fair. In all too many cases, it is neither. It has become readily apparent to those who have studied the issue that the abysmal representation of court-appointed counsel in death-penalty cases is the single most spectacular failure in the administration of criminal justice in America.15 The McFarland case is but a small slice of a very large pie.

The National Law Journal, after an extensive study of capital cases in six Southern states, found that capital trials are “more like a random flip of the coin than a delicate balancing of the scales” because the defense lawyer is too often “ill trained, unprepared…[and] grossly underpaid.”16

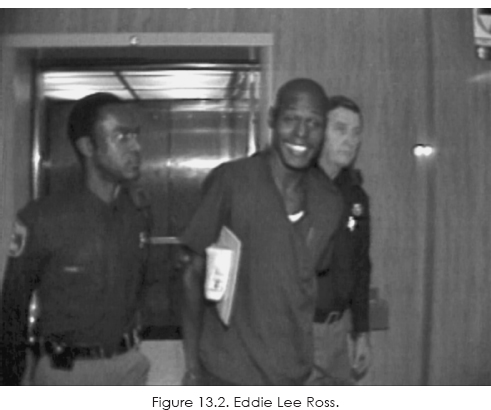

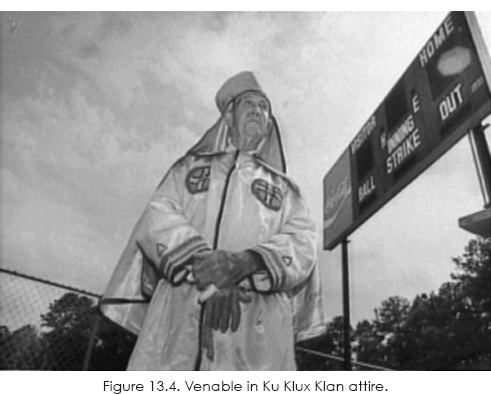

Like George McFarland, Eddie Lee Ross—charged with a gruesome murder in DeKalb County, Georgia, in 1983—didn't want to take a chance on a court-appointed lawyer. Or at least his family didn't. They were black and had little cash, but they scraped together whatever they could to hire seventy-seven-year-old James Venable to represent their son. What they didn't know was that Venable was also a former imperial wizard of the Ku Klux Klan in Georgia. For fifty consecutive years, he had hosted Klan rallies on Labor Day at Stone Mountain, Georgia, replete with cross-burning ceremonies.

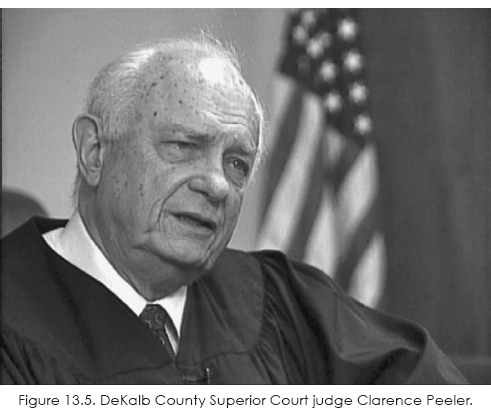

Venable also slept through portions of the trial and sometimes didn't even show up. Recognizing a problem, presiding judge Clarence Peeler appointed back-up counsel. But unlike in the McFarland case, here the two lawyers could never agree on who was in charge and what strategy would be best for their client.

Venable wanted Ross to testify. The court-appointed lawyer adamantly resisted, believing it might undermine his own trial strategy of portraying Ross as merely a deeply troubled and disadvantaged youth. At the close of the state's case and without any preparation, Venable called Ross to the witness stand, where Ross proceeded to self-destruct.

Whether to testify or to assert one's Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination can often be a difficult choice. Here, Venable's strategy made a conviction and death sentence all but inevitable. Did he have his client's best interest at heart? Was it merely a strategic error? During the course of the trial, Venable from time to time did show some hostility toward his client, referring to Ross in open court as a “nigger.”17

We went to DeKalb County, Georgia, to interview the presiding superior court judge Clarence Peeler about this. We found a warm, friendly, soft-spoken Southern gentleman who confirmed that Venable had repeatedly resorted to racial slurs during the course of the defense of his African American client.

Did that not trouble you?” we asked. “No, not at all,” said Peeler, “because I knew him to be a good lawyer who would do a good job.”18 Ross was convicted and sentenced to death in Georgia's electric chair.

The Georgia Supreme Court did not have quite as lofty an assessment of Venable's performance. It threw out Ross's death sentence on the ground of incompetent counsel. Venable later agreed to stop practicing law after the state bar association threatened to disbar him for senility.19

In the end, the experience may have been a lucky break for Ross. The crime he was convicted of was particularly brutal and the case against him was strong. According to his own statement to police, it was shortly after 5:30 in the morning when Ross, using a screwdriver, pried open the back window of the home of eighty-seven-year-old grandmother Ellen Funderburg. After rummaging around for money, Ross entered Mrs. Funderburg's bedroom and for some reason started bashing her with a vase.20

The Georgia Supreme Court, in its statement of the facts, picks up the story from there, quoting from Ross's statement to police.

She woke up and screamed, to which he responded by stabbing her with a pair of scissors. She quit screaming. Then he “started to have sex with her.” However, he only “juked about one or two times,” and quit, because he “realized that wasn't me, you know.” Ross got $11 in cash and some credit cards out of the victim's purse, took a wedding ring off the victim's finger, and took some other jewelry and some checks that he found in the house. He pawned one of the rings for $15 and then filled out one of the checks and tried unsuccessfully to cash it at a bank across the street from South DeKalb Mall. Next, he went to the mall and bought [a] radio, using the victim's credit card. That purchase, Ross recognized with regret, led to his arrest.21

It was about ten in the morning when Mrs. Funderburg's daughter stopped by just to say hello, as she frequently did. Immediately upon entering, Vivian Turner discovered that the house had been ransacked. She found the partially nude body of her mother lying on the bedroom floor, the handle end of a large pair of scissors protruding from her chest.

If Georgia is to have capital punishment, Eddie Lee Ross would seem to qualify absent some mental disease or defect not reflected in the police or court record. The Ross case stands for the proposition that it is not just the defendant who is harmed when the state fails to insure that a defendant on trial for his life is adequately represented. The state suffers, too. The failure to provide truly effective assistance of counsel raises the prospect that an innocent person is convicted, allowing the real murderer to go free.

But it can also mean that one who is clearly guilty of a horrible crime is not adequately punished or is not punished at all. In this case, Ross pleaded guilty rather than face a new trial. In exchange for his plea, he was sentenced to life in prison. He remains today in the custody of the Georgia Department of Corrections.

The murder rate in the United States has been declining over the last decade, but there are still around fifteen thousand homicides a year. The number of death sentences returned in recent years is also on the decline, now just over a hundred annually. Statistically, less than one percent of the homicides result in a death sentence. Most of the homicides do not satisfy the statutory requirements of a death sentence. Of those that do, whether a defendant lives or dies often depends on the competence and the tenacity of the defense lawyer.

The case of Rebecca Machetti and John Eldon Smith, coconspirators in a murder in Bibb County, Georgia, is illustrative. The crime is one of the most notorious in Bibb County history, and it resulted in Machetti becoming the only female on death row and Smith becoming the first person to actually be executed in Georgia following the reinstatement of capital punishment by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1976.

Machetti and Smith had schemed to murder Machetti's ex-husband, who had recently remarried. The plan was not the product of a spurned heart; rather it was simple greed. Machetti and Smith wanted to cash in her ex's $20,000 life-insurance policy. Machetti was the “brains” behind the operation, the “mastermind.” Initially, she wanted to poison her ex-husband. But then she got to thinking in grander terms. The Mafia, she felt, could use a few good hit men, and her new husband might make a favorable impression by knocking off her old one. He would have to change his name, of course. Something with a little more Mafioso panache. Smith started going by the name of “Anthony Isalldo Machetti.”22

If the name fit, the face and body didn't. Short, bald, chubby, with a walrus-like moustache, he looked every bit the TV repairman he pretended to be when he showed up at the home of Ronald Akins and his wife of twenty days, Juanita Akins. But he did the job, shooting them both dead at point-blank range with a 12-gauge shotgun. Juanita was killed solely because she was there, at the wrong place and the wrong time.23

Both Machetti and Smith were charged with capital murder, convicted in separate trials, and sentenced to death. Both had their death sentences affirmed by the Georgia Supreme Court. They had one other thing in common, too. In each case, women had been systematically, and unconstitutionally, excluded from jury service. Neither defendant was judged by an impartial jury of one's peers as the Sixth Amendment requires. The Supreme Court had struck down gender discrimination in jury selection only a few weeks earlier. The attorney for Machetti knew of the decision and knew enough to object promptly in state court. The attorney for Smith was unaware and failed to object. The Eleventh U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ordered a new trial for Machetti. The court, however, refused to consider the identical issue in Smith's case because his lawyers had failed to preserve it with a timely objection.24

On December 15, 1983, the state of Georgia put John Eldon Smith to death at the Georgia Diagnostic and Treatment Center, fifty miles south of Atlanta. “Hey there ain't no point in pulling the straps so tight,” protested Smith mildly, as prison guards strapped him into the state's brand-spanking-new electric chair. The execution made national news as evidence that the death penalty was back. United Press International sent out the news under the headline (adopted in many newspapers around the country): “Apprentice Hit Man Is Second Person Executed in Two Days.”25

Machetti, however, was spared. In her new trial, with a more representative and more constitutional jury, she was given two life terms. Unlike today, “life in prison” in 1983 seldom really meant life in prison. Machetti was released on parole in June 2010 after having served thirty-six years in prison.26

Had Machetti been represented by Smith's lawyers in state court and Smith by Machetti's lawyers, Machetti would have been executed and Smith would have obtained federal habeas corpus relief.

So was the imposition of the death penalty because the crime was so bad or because the perpetrator was so incorrigible? Or might it be more a reflection of Smith's inadequate representation in court?

Stephen Bright, president of the Southern Center for Human Rights, is an outspoken opponent of capital punishment in all cases. He says that “a large part of the death row population is made up of people who are distinguished by neither their records nor the circumstances of their crimes, but by their abject poverty, debilitating mental impairments, minimal intelligence and the poor legal representation they received.”27

Writing in the Yale Law Journal, Bright quotes a member of the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles, saying that if the files of one hundred cases punished by death and one hundred punished by life were shuffled, it would be impossible to sort them out by sentence based upon information in the files about the crime and the offender.28

George McFarland and Eddie Lee Ross had hired their own lawyers in the belief that court-appointed lawyers might not defend them as zealously as hired ones. While the strategy might not have worked for them, there is some validity to the underlying premise. Statistically, there is research showing that roughly 75 percent of capital defendants represented by court-appointed lawyers end up getting a death sentence. But only about a third of those represented by hired counsel go to death row.29 A more recent study of the federal death penalty indicates that the greater the financial resources made available to the defense in a case, the less likely a death sentence will be handed down.30

According to the Death Penalty Information Center, which keeps tabs on such matters, the costs of defending a capital case are out of reach for most Americans. The center's executive director, Richard Dieter, says, “The reality today is that virtually no defendant can afford to hire fully adequate death penalty representation.” Asked about research, he wryly replied, “The people with that kind of cash on hand probably are not going to face the death penalty very often, so it would be hard to do a reliable study of comparison.”31

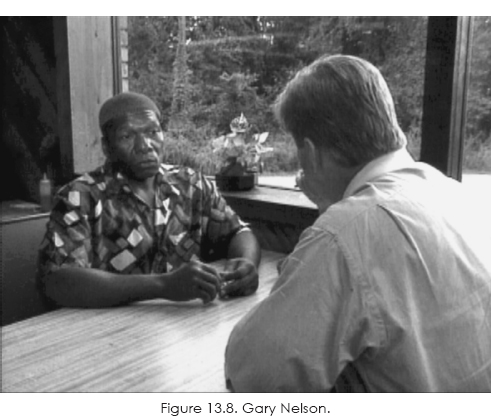

The vast majority of defendants in capital cases don't have the resources to hire a private attorney and have to take whatever the court will provide.32 So it was for Gary Nelson, convicted and sentenced to death, though it turned out the state never had much of a case against him.

The case against Nelson was premised largely on a hair found on the victim's body that a prosecution witness testified could have come from Nelson. Nelson's attorney, Howard McGlasson, hired no investigators and offered no rebuttal witnesses. McGlasson (who was later disbarred on unrelated matters) was defensive when we caught up with him years later: “Out of what money, sir? I mean, you know, you've got to realize I was barely paying my rent, barely paying my mortgage, barely putting food on my table.”33 McGlasson was paid only between fifteen and twenty dollars an hour; his request for cocounsel was denied. He didn't even ask for an investigator, believing he did not stand a chance of getting one.

In subsequent appeals, Nelson was represented by attorneys who were willing to put up some of their own money to challenge the state's testimony on the hair evidence. It turned out the Federal Bureau of Investigation had previously determined the hair was in no condition to be linked to anyone, including Nelson. The Eleventh U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals eventually threw out Nelson's conviction for insufficient evidence, but only after he had spent eleven years on death row.34

Nelson later told us, “I had little or no representation. I knew he was a court-appointed attorney and I really didn't expect nothing from him. And he didn't give me anything.”35

These horror stories are not uncommon. Defendants on trial for their lives are typically represented by the “bottom of the bar”36 and often have no representation at all in appeal and post-conviction proceedings.

It should come as no surprise that the level of representation accorded many capital defendants in these cases violates the Sixth Amendment guarantee of the effective assistance of counsel. What is remarkable, however, is the large number of cases where the courts have held the fundamental right to counsel had not been violated, notwithstanding what would appear to be egregious representation.

In 1984, the U.S. Supreme Court set out a two-part test for competency in the case of Strickland v. Washington.37 To establish that one has been denied the effective assistance of counsel, the defendant must show that “counsel's representation fell below an objective standard of reasonableness” and that “there is a reasonable probability that, but for counsel's unprofessional errors, the result of the proceeding would have been different.” Writing for the majority, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor warned that the “scrutiny of counsel's performance must be highly deferential,” noting that it “is all too tempting to second-guess a lawyer's performance after the fact, and that courts should try to ‘eliminate the distorting effects of hindsight.’”38

The language of the opinion in Strickland v. Washington made it easier for the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals to find attorney John Benn's dozing off to be part of a strategy that should not be second-guessed through “the distorting effect of hindsight.” In Strickland itself, the Court upheld a death sentence even though the defendant's lawyer chose not to offer any mitigating evidence at all at the sentencing phase of the trial, although there was plenty of information that would have helped Washington and could well have saved his life.39 Justice Thurgood Marshall dissented.

Among other things, Marshall took issue with the Court's pronouncement that trial lawyers must have wide latitude and that reviewing courts must be “deferential.” Much of the work, he felt, is subject to uniform standards such as applying for bail, conferring with one's clients, making timely objections to questionable rulings by the trial judge, meeting deadlines for motions and appeal notices. Marshall suggested failure to meet those standards should not be subject to any deference at all.

Marshall also took issue with the majority's view that the determination of whether a defendant's right to counsel was effective should hang on the fairness of the outcome. The fairness of the procedure, said Marshall, matters just as much. “The majority contends that the Sixth Amendment is not violated when a manifestly guilty defendant is convicted after a trial in which he was represented by a manifestly ineffective attorney. I cannot agree.”40

Marshall also argued that attorneys in capital cases should be held to a higher standard than those in noncapital cases given the severity and irrevocability of a death sentence. The Supreme Court itself has been through a gauntlet of test cases, much of it documented in this book, that has left death-penalty litigation more complex than ever.

The Court's majority, and the legislatures of states desiring capital punishment, would have done well to heed Justice Marshall's advice. The quality of representation in the years since the Strickland decision was announced does not appear to have gotten any better. Death-penalty critics make a strong case that it has only degenerated further, quite often attributing the decline to the high Court's decision in Washington v. Strickland.41

Most court-appointed lawyers simply do not have the training necessary to represent someone on trial for his life. The playing field is anything but level. As Stephen Bright put it in his Yale Law Journal article,

Many death penalty states have two state-funded offices that specialize in handling serious criminal cases. Both employ attorneys who generally spend years—some even their entire careers—handling criminal cases. Both pay decent annual salaries and provide health care and retirement benefits. Both send their employees to conferences and continuing legal education programs each year to keep them up to date on the latest developments in the law. Both have at their disposal a stable of investigative agencies, a wide range of experts and mental health professionals anxious to help develop and interpret facts favorable to their side. Unfortunately, however, in many states both of these offices are on the same side: the prosecution.42

In general, court-appointed lawyers, and many private attorneys, are simply no match for the professionals working for the district attorney and in the offices of the state attorney general. In fact, according to one study, in the states with the largest number of death sentences, a third of the lawyers practiced mostly civil law and most had never handled a capital case before. And having tried it once, more than half said they'd never do it again.43

In addition to extensive training, capital cases also take a great deal of time. And yet, states pay next to nothing for the work. The rates vary not only from state to state but also from county to county and city to city. In Philadelphia, court-appointed attorneys in capital cases have recently been getting only about forty dollars an hour for preparation time.44 No wonder there might be little pretrial preparation. For years, Alabama had set a flat rate of $2,000 for trial preparation, even though a good capital defense could easily run up a thousand hours of work. That has since changed but, as of this writing, they are paid around only seventy dollars an hour, and Alabama law does not require any death-penalty litigation experience when representing clients on trial for their lives.45 Often judges end up having to choose from the least able or least experienced lawyers, those who cannot get clients any other way.46

The Houston Chronicle reports that Texas lawyers have repeatedly missed filing deadlines between 2009 and 2011, resulting in the dismissal of their clients’ appeals. At least six of those clients have since been executed. Taxpayers appear loathe to pay the price for adequate representation of those charged with murder.47 The defendants are generally poor, disproportionately of color, often afflicted with mental disabilities, and always accused of a horrible crime. And when the community talks about “justice,” it is more in the nature of revenge than of a just legal system and the guarantee of a fair trial.

And even if they wanted to, providing true justice may be beyond the means of some jurisdictions. Consider the case of Robert Haggart, accused of shooting seven people to death—three of them children—in one of the worst crimes in Michigan history.48 The crime occurred in 1982 in Clare County, which, with a 19 percent unemployment rate and $3,700 per capita income, ranked among the poorest counties in the state. Yet getting the case to trial meant staggering expenses: Haggert fled to Tennessee and had to be brought back to Michigan along with many of the witnesses. That cost an estimated $24,000. Add in $40,000 for police overtime, $4,500 for autopsies and other lab work, plus the cost of attorneys, and the total bill came to over $200,000, or 7 percent of the county's annual budget. Trash collection was reduced to once a week; school budgets were frozen.

The victims were lifelong residents of the area, widely known and well liked. The murders traumatized the community, as did the bill. Charged with both prosecuting and defending an accused mass murderer, the county was left in the worst financial straits in its history, with no one to turn to for help. Haggart ended up being sentenced to life in prison without parole. He died in prison in 2003. Clare County did what it had to do. After all, the right to a fair trial is fundamental. Courts may be standing in line to guarantee it, but as the citizens of Clare County sadly learned, no one is standing in line to pay for it.

Add to all of the above that many clients tend to be undesirable from a variety of standpoints. Many have actually committed the horrible crimes of which they are accused. While they are still entitled to a fair trial, there can be social pressure against taking on such clients, particularly in small, rural communities where many capital crimes arise. In sum, the work is hard, a defendant's life is on the line, the hours are long, and the pay is low. And when all else fails, the capital defendant's final resort is to challenge the competency of his lawyer. It is all but guaranteed, even in many cases where counsel performed exemplary service.

The climate has improved somewhat in recent years. In 1994, the Court extended the right to counsel beyond the trial and direct appeals to federal habeas corpus petitions. Even after all direct appeals have been exhausted, a defendant in state court has the right to challenge the fairness of his trial in federal court, and counsel must be provided in death-penalty cases.49

The Court has also somewhat refined its decision in Strickland. Lower courts may not have carte blanche to second-guess a defense lawyer's strategy of not providing any mitigating evidence at the punishment phase of a capital trial, but the attorney still must undertake a meaningful inquiry to determine what mitigating evidence might exist. The Supreme Court ruled in 2003 that the failure to even research and consider factors that might result in mercy is per se ineffective assistance of counsel.50

More still needs to be done. The American Law Institute (ALI),51 made up of about four thousand judges, lawyers, and law professors, was instrumental in drafting the framework for capital punishment legislation that the Supreme Court upheld in Gregg v. Georgia (setting the stage for a revival of capital punishment in thirty-eight states). But in October 2009, the ALI pronounced the project a failure, citing among other things the apparent and historic inability of states to fund competent defense counsel. In backing off from what had at one time been considered a monumental achievement, the ALI cited “the current intractable institutional and structural obstacles to ensuring a minimally adequate system for administering capital punishment.”52

Since 1997, the American Bar Association has called for a moratorium on executions in large part because of the failure to provide adequate counsel to defendants on trial for their lives. Citing the “quality of legal representation that capital defendants receive and the fairness of capital proceedings,” ABA president Laurel Bellows says the association “encourages jurisdictions not to carry out executions until critical reforms are implemented.” Although the association opposes the death penalty for juvenile offenders and mentally impaired defendants, it has not taken a position on the death penalty itself.53

The right to counsel in death-penalty cases since the Supreme Court reinstated capital punishment in 1976 has been, at best, illusory, raising the question of whether it can ever be “done right.” Whatever one's position on capital punishment, and particularly for those who might embrace it, this condition is intolerable and needs to be remedied. The chronic failure to provide effective assistance of counsel, compounded by the slim prospect of improvement, has emerged as one of the leading arguments for doing away with capital punishment once and for all.

|

For a video report on ineffective assistance of counsel, go to: http://murderatthesupremecourt.com/counsel |