Apparent disparities in sentencing are an inevitable part of our criminal justice system.

—Justice Lewis Powell, ruling in McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279 (1987)

On a Saturday morning in 1978, Warren McCleskey and three of his friends drove around Marietta, Georgia, in a beat-up blue Pontiac, predators looking for likely prey. They found it in Atlanta, instead, after lunch.

The quartet, all African American and with spotty criminal records, had gone to Marietta, a suburb of Atlanta, to case a jewelry store. They decided not to rob it, later picking what appeared to be a better target downtown: the Dixie Furniture store, which sat on a commercial strip of Marietta Street. McCleskey parked the Pontiac nearby and, while his three partners waited, went to check out the store.1

He talked with Dixie cashier Marie Thomas about a fictional gift purchase while looking over the store and the whereabouts of its employees. Afterward, McCleskey returned to the car and worked out a plan with the others; the four men then piled out of the car and headed for the store. McCleskey entered the front door, carrying a .38 caliber Rossi nickel-plated revolver; one man, holding a sawed-off shotgun, went in the back door accompanied by the other two, both of whom were carrying pistols.2

The nine Dixie employees were herded to a back room, tied up with tape, and forced to lie down on the floor. Owner William Dukes handed over $4,100 from the store safe, along with his watch and the six dollars in his pocket.3 Somewhere in this process, one of the employees managed to activate a silent alarm. It would summon Officer Frank Schlatt, a white policeman, to his death.

This kind of alarm call was common for police officers. “You can answer three or four a night and there'll be nothing to them,” said Philip Autrey, who regularly patrolled the downtown area in a squad car. Officers would respond alone. “With the current shortage of police officers, we're patrolling one man in a car, and we do not send backups,” said Atlanta police lieutenant B. G. Hodnett shortly after the incident. “It's a bad situation for us.”4

Frank Schlatt, thirty-one years old, had been on the force for five years. His colleagues regarded him as cautious and careful; he was no cowboy, they said, but he tried to be prepared for trouble. He had his gun in his hand when he entered the furniture store.5

Warren McCleskey fired first—two quick shots. One of the .38 caliber bullets ricocheted harmlessly from a cigarette lighter in Schlatt's pocket. The other hit him full in the face and killed him. McCleskey and his accomplices fled, leaving Frank Schlatt mortally wounded, bleeding out on the store's floor. He was so badly injured that Hodnett, his supervisor, did not recognize him when he arrived at the scene. Schlatt left behind a wife and a young daughter.

The manhunt was massive. Police got their first break after McCleskey was arrested in connection with another armed robbery in nearby Cobb County. During questioning, he admitted to participating in the Dixie robbery, but he denied shooting Schlatt. McCleskey would be done in, however, by his later admissions while in custody, to a codefendant and to an inmate in the next jail cell. Furthermore, two of his accomplices in the Dixie robbery would turn on him.

The evidence looked formidable to John Turner, hired by McCleskey's sister to defend him in the Dixie robbery case. An experienced former federal prosecutor, Turner urged McCleskey to plead guilty in exchange for a life sentence. “In a death-penalty case, if you can get a life sentence, you take it and run,” Turner recalled years later. “But he didn't want to hear it. He was stubborn.”6

The chief witness against McCleskey was Ben Wright, the accomplice who had entered the rear of the Dixie store with a sawed-off shotgun. An experienced felon—he had served fifteen years in prison for another armed robbery—Wright began building his defense strategy as soon as he heard the shots from the front of the store.

Wright was in the back, tying up one of the employees, according to the recollections of the prosecutor in the case, Russell Parker. “When the shots were fired,” said Parker in an interview, “he told this person ‘I'm taking your watch—you remember where I was at the time the shots were fired.’”7

“Ben Wright was a scary guy,” said Thomas Thrash, then a young attorney assisting Parker. He remembers the two of them interviewing Wright about the details of the robbery over a dinner of fried chicken at police headquarters. “For a twenty-six-year-old kid two years out of Harvard Law School, this was a different experience than I was used to,” Thrash told us.8 Thrash is now a federal district judge in Georgia.

Wright was the star witness when the Dixie robbery case went to trial in the cavernous Fulton County courtroom of Judge Sam Phillips McKenzie. He testified that he was in the back room at the time of the shooting, but that McCleskey later told him what happened. “He said the police slipped up on him before he knew it,” Wright testified, “and he said he shot him twice.”9

McCleskey took the stand in his own defense, coming across as “cold and emotionally detached,” according to Thrash.10 The defendant said his admissions to police had been coerced, and he claimed he'd actually been playing cards elsewhere at the time of the robbery. There were no witnesses to back up his story, and McCleskey played a very weak hand from the witness stand:

Turner: Were you at the Dixie Furniture Store that day?

McCleskey: No.

Turner: Did you shoot anyone?

McCleskey: No, I didn't.

Turner: Is everything you have said the truth?

McCleskey: Positive.11

Marie Thomas, the Dixie cashier, was one of the picture cards in Russell Parker's deck. She identified McCleskey as the man who had talked with her about a purchase just before the robbery occurred, and she also said she was “one hundred percent sure” that he was the robber who later entered the store with a gun and shot Officer Schlatt.12

Then Parker played his ace. A jailhouse snitch named Offie Evans told the jury that he was in the cell next to McCleskey, that he gained McCleskey's confidence, and that McCleskey told him it was a simple case of shooting Schlatt or getting caught. He quoted McCleskey as saying, “It would have been the same thing if it had been a dozen of them.”13

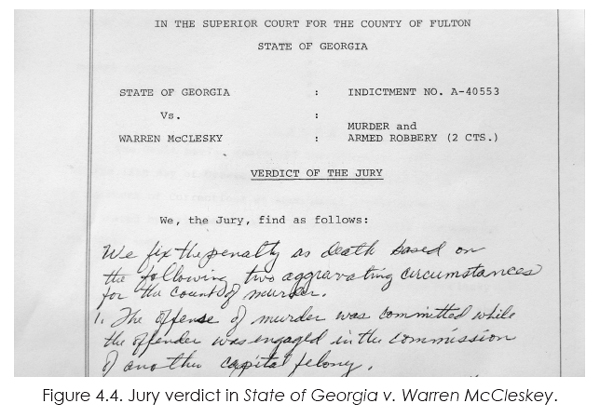

The game was over. The racially mixed jury took only two hours to return a verdict of guilty. “I don't think anyone in the courtroom was surprised,” said Judge Thrash. “The evidence against McCleskey was overwhelming.”14

In accordance with the 1976 Supreme Court mandate in Gregg v. Georgia, the jury then heard evidence in a sentencing hearing. Prosecutor Parker established two aggravating circumstances in connection with the murder: that it was committed during the course of another felony (the robbery) and that the victim was a police officer. Parker requested a verdict of death. “Have you observed any repentance by Mr. McCleskey?” he asked the jury. “Has he exhibited any sorrow? Have you seen any tears in his eyes for this act he has done?”15 The defense, unaccountably, offered no evidence of mitigating circumstances on McCleskey's behalf.

There had been only one previous death sentence meted out in Georgia since the Gregg decision restored capital punishment, and Fulton County had a reputation for “liberal” juries. But Parker had some vigorous local support for his argument. “The law enforcement community felt very strongly that the death penalty was an appropriate punishment for the murder of a police officer struck down in the line of duty,” recalled Judge Thrash.16

Again the jury deliberated for two hours, and the courtroom was hushed as the twelve members filed slowly back into the jury box. The verdict slip was passed to Judge McKenzie, who read it silently and passed it to the clerk who would announce the jury's decision to the courtroom. “It was a moment filled with emotional tension, I would say,” remembered Thrash. The clerk read the verdict: death. Sue Schlatt, widow of the slain policeman, wept.17

Moments later, Judge McKenzie pronounced the formal sentence: death by electrocution.

The sentence was front-page news in Georgia, but, as is often the case, it attracted little press attention elsewhere in the country. But at 99 Hudson Street in Manhattan, the McCleskey sentence soon came under very close scrutiny. It was there, at the offices of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund (LDF), that lawyers were sifting through death-penalty cases in search of vehicles for testing the latest strategic weapon in the LDF arsenal: statistical research suggested a relationship between a defendant's race and being sentenced to death row.

The LDF had arranged foundation funding for a major statistical study of death sentencing, which was to be directed by the highly respected University of Iowa professor David Baldus. The study was designed to be independent, despite the LDF's role in its financing. But the results were clearly welcome on Hudson Street.

Baldus's researchers delved into 2,484 murder cases in Georgia between 1973 and 1979. They examined police, prison, and parole files, building a meticulous database that attempted to account for major statistical variables. Their findings on racial factors defied conventional liberal wisdom: blacks were not condemned to death more often than whites. There was no link, according to the statistical analysis, between a defendant's race and the probability of a death sentence.

What was striking was the study's conclusion that the race of the victim was a significant factor: defendants charged with the murder of whites were over four times more likely to be sentenced to death in Georgia than those charged with killing blacks.18 The lawyers for the LDF viewed this statistical finding as a potential silver bullet in their fight against capital punishment. They decided—after much internal debate over the merits of its application in this particular case—to fire that bullet in defense of Warren McCleskey's life.

They used it first in a brief to Judge Owen Forrester of the U.S. District Court for northern Georgia. Forrester, a Reagan appointee who had already turned down a McCleskey request for a federal hearing, was an unlikely target. But the silver bullet had its desired effect: Forrester found Baldus's research intriguing enough to make it the subject of a full hearing.

In the end, despite extensive evidence and testimony offered by Baldus in Forrester's courtroom, the judge was not convinced. He determined that the evidence did not support the LDF argument that Georgia's legal system was so tainted by racial discrimination that its implementation of the death penalty should be declared unconstitutional. His ruling set the stage for further federal appeals on the bias issue that would eventually reach the U.S. Supreme Court.

As a curious sidenote, Judge Forrester developed doubts about testimony at McCleskey's trial made by the jailhouse snitch, Offie Evans. Forrester concluded that the jury should have been informed that detectives had offered to “speak a word” for Evans concerning his own charges in return for the testimony against McCleskey. This, despite the fact that everyone involved except for Offie had denied that he had been made an offer of any kind. A federal appeals court rejected Forrester's doubts.

But it was the Baldus research and the issue of racial disparity that earned McCleskey a slot on the Supreme Court's docket—but only by a whisker. Edward Lazarus, a former clerk to Justice Harry Blackmun and modern historian of the Court, discovered that McCleskey got the bare minimum of four votes necessary for a hearing: Justices Thurgood Marshall, William Brennan, Harry Blackmun, and John Paul Stevens. Not one of the Court's five conservative justices voted to accept the case.19

Inside the Court, Justice Byron White was already engaged in an examination of the Baldus study. Staying ahead of the game was typical of White's competitive approach to life; a former All-American turned professional football player, he had brought his sports ethic into the Court's marble palace. During breaks from work, White's chambers served as a putting green for him and some of his clerks. A putt would be hit in one office and have to travel across another to the justice's office, under the side of his couch, and out through its front legs. White won these contests with what some clerks viewed as a discouraging frequency.20 They were a momentary escape from the weighty cases that consumed most of his working days.

Even before the McCleskey petition reached the clerk's office, White had begun a preemptive attack on the LDF's argument. Having become interested in the Baldus study when its results began to surface in 1985, he assigned one of his clerks to research it. Under White's microscope, the Baldus findings “cut no ice,” as one of his clerks confided to Lazarus.21 White didn't trust the statistics. He took the unusual step, before the case was heard, of sending a memo to his conservative colleagues urging a vote against McCleskey. He pressed Justices William Rehnquist, Lewis Powell, Sandra Day O'Connor, and Antonin Scalia to reject the LDF claims.22

White had lit a backfire before the LDF could light a match; the conservative justices conferred among themselves about his memo. By the time oral arguments were heard on October 15, 1986, the die was cast. “For all practical purposes,” as Lazarus put it, “the fix was already in.”23

Jack Borger, the LDF attorney who rose to make the McCleskey case that morning, had no idea of the odds against him.24 He soldiered on. “There was a time,” he told the justices, “before our nation's Civil War, when free blacks and slaves alike could be given a death sentence merely for the crime of assault on a Georgia white citizen…. Today, we are before the Court with a substantial body of evidence indicating that during the last decade Georgia prosecutors and juries…have continued to act as if some of those old statutes were still on the books.”

Borger came under skeptical questioning from White, who leaned forward, scowling, as he challenged the LDF's position and the Baldus study. David Baldus watched helplessly from the gallery of the courtroom as he saw White's vote slip away. White, who had voted to overturn William Furman's death sentence, offered no hope in the McCleskey case.

White was not Borger's only challenger. Borger also got sharp questions from William Rehnquist, just installed as chief justice, Justice Lewis Powell, and newly appointed Justice Antonin Scalia. Scalia was at his most sardonic: “Now, what if you do a statistical study that shows beyond question that people who are naturally shifty-eyed are, to a disproportionate extent, convicted in criminal cases? Does that make the criminal process unlawful?”

And when Borger made the point that murderers of whites were more at risk of death than murderers of blacks, Justice O'Connor turned his logic on its head: “What's the remedy?” she asked. “Is it to execute more people?”

If the die was cast before oral arguments, it was hardened into steel by the time the justices convened in their second-floor Conference Room two days later. Justice White, taking nothing for granted, had circulated another memo urging that McCleskey's death verdict be affirmed. And it was, in Conference, by a vote of 5–4. The composition of the Court had changed since the case had been accepted—Rehnquist moved into Burger's seat as chief justice, and Antonin Scalia joined the Court to fill Rehnquist's place—but the balance on the Court had not changed. Rehnquist, O'Connor, Powell, Scalia, and White voted to affirm McCleskey's death sentence; Blackmun, Brennan, Marshall, and Stevens voted futilely to overturn it.

White very much wanted to write the Court's opinion, Lazarus tells us, but Rehnquist assigned it to Powell, who had rejected the principal LDF-Baldus argument out of hand: “At most, the Baldus study indicates a discrepancy that appears to correlate with race,” Powell wrote. “Apparent disparities in sentencing are an inevitable part of our criminal justice system…. We hold that the Baldus study does not demonstrate a constitutionally significant risk of racial bias affecting the Georgia capital sentencing process.”25 Justice Brennan wrote the dissent, joined by Blackmun, Marshall, and Stevens, saying the Baldus evidence “relentlessly documents the risk that McCleskey's sentence was influenced by racial considerations.”26 Stevens concluded, in an additional separate opinion, that McCleskey would not be on death row “if he had killed a member of his own race.” He continued, “This sort of disparity is constitutionally intolerable. It flagrantly violates the court's prior insistence that capital punishment be imposed fairly…or not at all.”

But no shadow of doubt appeared in Powell's opinion for the majority: the verdict and the sentence were constitutional, and the State of Georgia had every legal right to put Warren McCleskey to death. The certainty is ironic, given the fact that Powell later regretted both his opinion and his vote in the case. That vote would not only have turned the case the other way, but it could have cast a pall of doubt on all death sentences involving black defendants and white victims. After his retirement, in fact, Powell said his views on capital punishment had changed radically.

In a retrospective interview with his biographer, John Jeffries, Powell was asked if he would change his vote in any of the cases that came before him:

Powell: Yes, McCleskey v. Kemp.

Jeffries: Do you mean you would now accept the argument from statistics?

Powell: No, I would vote the other way in any capital case.

Jeffries: In any capital case?

Powell: Yes.

Jeffries: Even in Furman v. Georgia?

Powell: Yes. I have come to think that capital punishment should be abolished.27

Powell's turnabout came much too late for Warren McCleskey. He was pronounced dead in Georgia's electric chair at 3:13 a.m. on September 25, 1991—but his final hours were chaotic and confusing.

McCleskey had been scheduled to die the previous day. His head was shaved that afternoon to provide better conductivity for the lethal electricity. Shortly afterward, he was served the final meal he had requested: pizza pockets, pinto beans, corn bread, and Kool-Aid. But by that time, he was no longer hungry; there was a lot to distract him.

As the execution hour of 7:00 p.m. approaches, McCleskey's lawyers file a last-minute appeal in federal court with Judge Owen Forrester. The clock ticks on relentlessly.

6:45 p.m. Forrester grants a stay, but only until 7:30 p.m.

7:20 p.m. Forrester grants a second stay, this one until 10:00 p.m., so that he can hear evidence in the case.

9:30 p.m. Judge Forrester orders yet another stay, this one until midnight, while he continues to hear evidence.

11:20 p.m. Forrester denies McCleskey's appeal but allows yet a fourth stay, this one until 2:00 a.m., so that his lawyers can appeal to a federal court of appeals.

1:50 a.m. the court of appeals lifts the stay. Prison officials reschedule the execution for 2:15 a.m.

2:19 a.m. McCleskey is strapped into the electric chair, but as he begins to make a last statement, Warden Walter Zant interrupts him to announce that the U.S. Supreme Court has issued a stay. McCleskey is removed from the chair and taken to his cell.

2:42 a.m. the Supreme Court issues another stay—this one for only ten minutes.

2:52 a.m. the Supreme Court denies McCleskey's appeal.28

One minute later, McCleskey is once again strapped into the electric chair. He makes a final statement to the group of witnesses seated on three polished oak benches on the other side of the chamber's glass. “I want to say to the family of Frank Schlatt, I hope you find in your hearts to forgive me for my participation in the crime,” he says. “I am ready to enter the kingdom of heaven.”29

At 3:06 a.m., three unidentified state employees hit identical red buttons—but only one of them is operational. It sends two thousand volts through McCleskey's body. The electricity is turned off at 3:08 a.m., and doctors wait for a five-minute “cooling off” period before approaching the body and pronouncing McCleskey dead.30

|

To hear an audio recording of the communications in the prison command post, go to: http://murderatthesupremecourt.com/mccleskey |

The legal kabuki dance during McCleskey's last hours concluded with a gaggle of the nation's most senior judges in their pajamas, huddling by telephones to decide if a forty-four-year-old inmate would live to see the light of a new day. They decided he would not.

The incident disgusted Justice Thurgood Marshall, who had already announced his retirement and was serving until his replacement could be confirmed by the U.S. Senate. Ever an opponent of capital punishment, Marshall was particularly exercised about the Court's action—or lack of it—in McCleskey's final hours.

“In refusing to grant a stay to review fully McCleskey's claims,” Marshall said, “the Court values expediency over human life. Repeatedly denying Warren McCleskey his constitutional rights is unacceptable. Executing him is inexcusable.”31 Jodie Swanner saw it differently. She was eleven years old when Warren McCleskey shot and killed her father, Officer Frank Schlatt, on Marietta Street. She said of McCleskey, “I never got to say goodbye to my father. This has nothing to do with vengeance. It has to do with justice.”32

Recalling her father, Schlatt's only daughter said, “I remember my father as a good man…. He believed in the justice system, and it's about time the justice system takes up for my father.”