It is indefensible to conclude that individuals who are mentally retarded are not to some degree less culpable for their criminal acts. By definition, such individuals have substantial limitations not shared by the general population. A moral and civilized society diminishes itself if its system of justice does not afford recognition and consideration of those limitations in a meaningful way.

—Justice Lawrence Koontz, dissenting in Commonwealth of Virginia v. Daryl Atkins

May 22, 1944

Casablanca, Morocco

Twenty-year-old Army private Albert Trop was being held in the base stockade for having been away without leave (AWOL). He found the conditions at the base intolerable. On this day in May, he managed to walk away from the stockade and the base itself with the idea of never coming back. He wanted to join up with his former unit in Italy, where life, he assumed, might be better. But it was cold and rainy, and he had no money, and he was hungry. His escapade lasted less than twenty-four hours. The next afternoon, he hopped an Army truck and returned to base. But he had been gone again, and this time there would be a higher price to pay.

Desertion in a time of war is a serious offense, even a technical desertion like Trop's. Although the government never suggested Trop was going over to the other side or refuted his claim that he wanted to reconnect with a former unit, he was still court-martialed, sentenced to three years at hard labor and loss of all pay, and given a dishonorable discharge. Eight years later, Trop applied for a passport and learned he had also lost his U.S. citizenship, a sanction authorized by Congress for desertion during wartime under Section 401(g) of the 1940 Nationality Act. His application for a passport was denied.

Trop didn't murder anyone and nobody murdered him. So, one might reasonably ask, why is his case in this book? Trop's subsequent appeal may have had as great of an impact—or greater—on capital punishment in the United States than most of the murder cases that have reached the Supreme Court. And it has contributed significantly to the debate and criticism over how the Court does, or should do, its work.

Trop argued that to deprive him of his U.S. citizenship, essentially leaving him a man without a country, was cruel and unusual punishment beyond the authority of Congress. The U.S. Supreme Court agreed, finding that the involuntary taking away of citizenship amounted to “the total destruction of the individual's status in organized society” and was in violation of the Eighth Amendment.1

The 1954 case of Albert Trop v. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles divided the Court, and it has, to some extent, divided every Supreme Court since. The vote was 5–4. The dissenters were led by an incredulous Justice Felix Frankfuter who—after pointing out that desertion from the military in wartime was punishable by death—asked rhetorically, “Is constitutional dialectic so empty of reason that it can be seriously urged that loss of citizenship is a fate worse than death?”

“At the outset, let us put to one side the death penalty as an index of the constitutional limit on punishment,” responded Chief Justice Earl Warren, adding that “the existence of the death penalty is not a license to the Government to devise any punishment short of death within the limit of its imagination.”

Warren went on to describe the history and meaning of the ban against cruel and unusual punishment with words that have reverberated through generations of Eighth Amendment cases, particularly those involving the death penalty:

The exact scope of the constitutional phrase “cruel and unusual” has not been detailed by this Court. But the basic policy reflected in these words is firmly established in the Anglo-American tradition of criminal justice. The phrase in our Constitution was taken directly from the English Declaration of Rights of 1688, and the principle it represents can be traced back to the Magna Carta. The basic concept underlying the Eighth Amendment is nothing less than the dignity of man. While the State has the power to punish, the Amendment stands to assure that this power be exercised within the limits of civilized standards. Fines, imprisonment and even execution may be imposed depending upon the enormity of the crime, but any technique outside the bounds of these traditional penalties is constitutionally suspect. This Court has had little occasion to give precise content to the Eighth Amendment, and, in an enlightened democracy such as ours, this is not surprising. But when the Court was confronted with a punishment of 12 years in irons at hard and painful labor imposed for the crime of falsifying public records, it did not hesitate to declare that the penalty was cruel in its excessiveness and unusual in its character. The Court recognized in that case that the words of the Amendment are not precise, and that their scope is not static. The Amendment must draw its meaning from the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.2 (emphasis added)

The Court clearly has the authority to draw some bright lines. Few would complain, for example, were it to prohibit the execution of an infant or of one who met the clinical definition of an idiot. But what about a defendant who is only mildly retarded, or a juvenile just shy of his eighteenth birthday but who has still shown himself to be a cold-blooded killer? In these gray zones, addressed in this and the subsequent chapter, the words of Chief Justice Earl Warren about “evolving standards of decency” echo loudly.

August 17, 1996

Hampton, Virginia

Thirty-two-year-old Garland Clay, the foreman for a plumbing and mechanical contractor, had had a long day. It was hot, and he was tired…and it was getting late. Clay was ready to join his coworkers for some billiards and a brew or two at their regular hangout, Petro's Tavern in Hampton. He got there around 9:00 p.m. and hung around until closing. He had consumed at least a six-pack of beer before heading home in the wee hours of the morning. On the way home, all that beer was starting to drain through his body. Clay got off of I-64 at the Lee Hall exit in hopes of finding a little wilderness—what hikers call “the green door”—to relieve himself.

It was now about 3:45 in the morning. As he turned off the road, Clay's headlights shined through some low-lying fog revealing what appeared to be a body stretched out alongside the road. Clay picks up the story in a crowded courtroom in Yorktown, Virginia, a few years later.

Virginia Commonwealth's Attorney Eileen Addison: Did you see anything unusual during those early morning hours?

Clay: You could say that. I came across some guy who appeared to be sleeping on the side of the road. And I stopped immediately, rolled my window down, and yelled twice and blew the horn and yelled a third time; and I got no response from him. And from what I could see, I didn't think I was going to.3

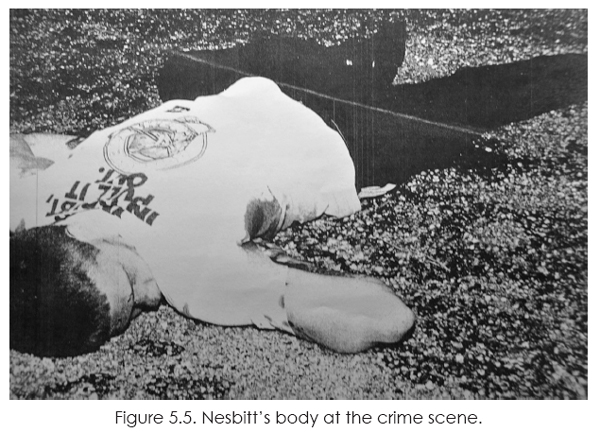

Upon closer examination, Clay saw the bullet-riddled body of a very young man. He drove to the first house he could find, woke the person who was living there, and had them call the police. Deputy Troy Lyons of the Major Crimes Unit of the York County Sheriff's Department said he got the call shortly before five in the morning and “was directed to the intersection of Crafford Road and Tower Road, where a body had been found.”4 Lyons would be the lead investigator of the case.

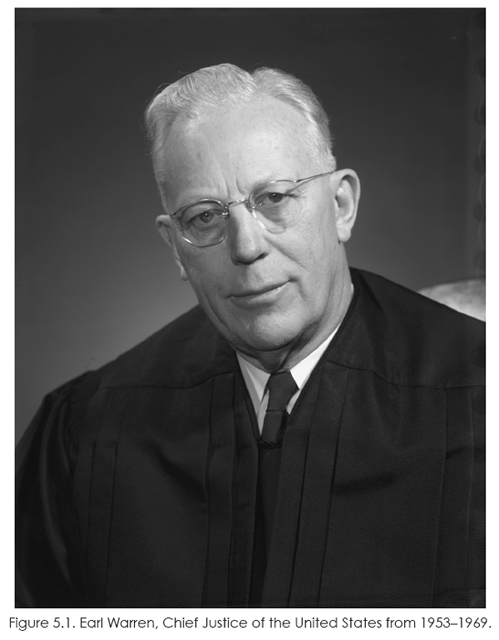

The victim's wallet was missing, leading Lyons to assume robbery was the motive. It had rained that night yet the victim's clothing was still relatively dry. This had just happened, he thought, and the pool of blood surrounding the body told him that it had happened right there, on the spot he was standing, not at some distant venue. Lyons also found a pay stub in the victim's pocket from Advance Auto Parts in Hampton that led to the identification of twenty-one-year-old Eric Nesbitt who worked at the store part-time. Apparently he was also an airman first class at the nearby Langley Air Force Base.

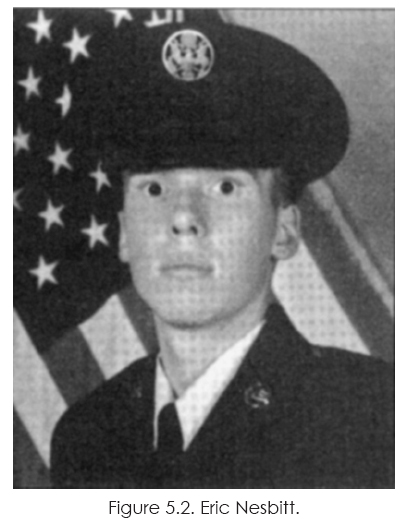

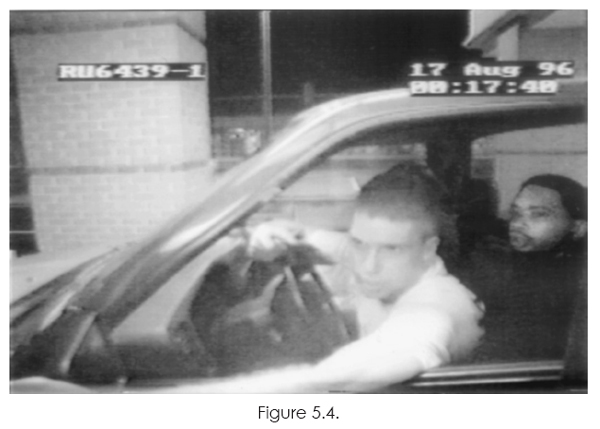

An important break in Nesbitt's murder case came three days after his body was found, when Lyons got a call from the local branch of Crestar Bank saying they had a video tape of Nesbitt making a $200 withdrawal from a local ATM on the night he was killed. In the video, Nesbitt can be seen seated in his pickup truck between two men, one of them holding a gun to his head.

Photographs made from the video were distributed to local newspapers and television stations, and it wasn't long before deputies received a number of “Crimeline” telephone tips that one “William Jones” appeared to match the man in the driver's seat in Nesbitt's truck. The truck itself turned up at a motel in Newport News, Virginia. Police maintained surveillance of the motel area, and when Jones returned, they promptly arrested him.

No one other than William Jones and the second man, subsequently identified as Daryl Atkins, can say what actually happened that night, but prosecutors—and apparently the jury—believed Jones's version, which was offered in exchange for leniency. The following story is now part of the official record in the lower courts and in the U.S. Supreme Court.5

Jones and Atkins were “drinking fruit juice and gin and smoking weed” at the home Atkins shared with his father. It continued late into the evening; friends came and went. One friend of Atkins's, Mark Dallas, showed up around 10:30 at night with a handgun. He gave it to Atkins, who said “that he wanted to use it and would bring it back in the morning.” An hour later, Atkins and Jones made one of several walks that day down to the 7-Eleven to buy some beer. Atkins told Jones he didn't have enough money and was going to panhandle to get what he needed, with the gun tucked behind the waistband of his pants, partially concealed by his belt buckle.

While Jones waited, Atkins approached several people to ask for money and collected a bit from one or two customers. Nesbitt arrived at the store in his 1995 Nissan pickup truck at around 11:30 p.m. After a brief conversation with Atkins, Nesbitt went into the store. When he came back out and got back in his truck, Atkins whistled at him. Nesbitt stopped and rolled down his window. That turned out to be a fatal mistake.

Atkins then went to the passenger's side of the truck; Jones, to the driver's side. Atkins pointed the handgun at Nesbitt's head and ordered him to “move over, let my friend drive.” Both men then entered the truck, and Jones drove off.

Atkins demanded that Nesbitt surrender his wallet. Atkins removed sixty dollars and, as he handed the wallet back, noticed Nesbitt's Crestar ATM card. On Atkins's instruction, Jones drove to a Crestar Bank ATM. Once there, Atkins forced Nesbitt to withdraw another $200. The security camera in this automatic teller machine recorded the truck arriving at the bank shortly after midnight on August 17, 1996. The videotape produced by the camera showed that Jones was driving, Atkins was in the passenger seat, and Nesbitt was between them. During this entire time, Atkins kept the handgun pointed at Nesbitt.

Jones then drove to the parking lot of a nearby school where he and Atkins discussed what they should do with Nesbitt. Jones urged Atkins to “just tie him up so we can get away.” Atkins told Jones he knew of a place near his grandfather's house in Yorktown where they could leave Nesbitt and directed Jones to drive toward Yorktown on Interstate 64. Nesbitt pleaded with them, saying “just don't hurt me” and made no attempt to escape.

Upon arriving in a secluded area off of I-64, Atkins exited the truck and ordered Nesbitt to do the same. “Nesbitt stepped out of the vehicle and probably took two steps” when Atkins began shooting him. Jones jumped out of the truck and tried to wrestle the gun from Atkins. In the ensuing struggle, Atkins was shot in the leg. Jones, now in control, drove Atkins to the emergency room of a local hospital, leaving Nesbitt's dead body at the scene of the shooting. Outside the emergency room, Jones asked Atkins for some of the money that had been taken from Nesbitt and then drove away, alone in Nesbitt's truck.

Jones then drove to the King James Motel in Newport News where he abandoned the truck. He spent the next several days moving from motel to motel. He cut his hair in an attempt to disguise his appearance. He subsequently returned to the first motel, where police were waiting and arrested him. The handgun was not found in the truck and was never recovered.

One of the “Crimeline” tipsters that turned police on to Jones reported that “a person that Mr. Jones runs with was a Daryl Atkins.”6 Jones's father confirmed to Deputy Lyons that Atkins was with his son on the night of the murder, and he provided Atkins's address. Lyons then went to Atkins's home, saw that Atkins matched the security camera photographs, and placed him under arrest.

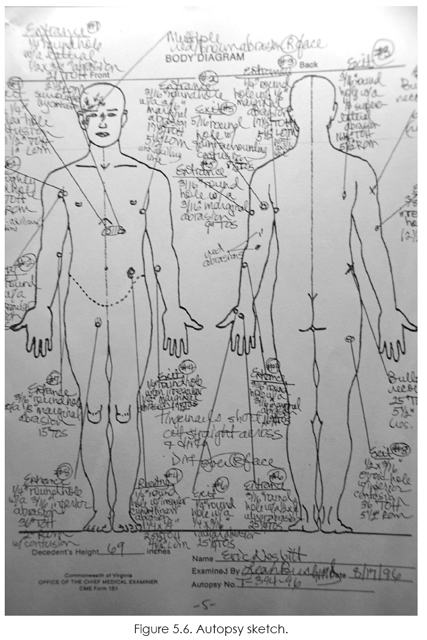

An autopsy revealed that Nesbitt had sustained eight separate gunshot wounds to the thorax, chest, abdomen, arms, and legs. Several of the bullets exited and reentered the body. Three of the gunshot wounds were lethal. However, the coroner concluded that Nesbitt could have lived for several minutes before “the bleeding was to the point where his blood pressure would not support consciousness and life.”7 Three bullets were recovered during the autopsy.

The gruesome details of the crime began to filter in. Although only eighteen years old at the time of the offense, Atkins had more than twenty felonies under his belt, including a burglary when he was only thirteen. Atkins was the only defense witness at the guilt phase of his trial, and his testimony sharply contradicted that of Jones. It was Jones who initiated the contact with the victim, insisted Atkins. It was Jones who forced his way into Nesbitt's truck. And it was Jones who fired the fatal shots. The jury, however, believed Jones, convicting Atkins of capital murder. Under Jones's agreement with the government, he pled guilty and was sentenced to life in prison.

The prosecution made clear that it would be seeking the death penalty for Atkins, citing both the “vileness” of the crime and Atkins's “future dangerousness” as the aggravating factors. Prosecutor Eileen Addison told the jury: “He could have simply pushed Eric Nesbitt out of that truck and left him stranded in the woods. He could have knocked him unconscious, he could have shot him in the leg so that he would have trouble getting to a house to get help. But that wasn't enough for Daryl Atkins. It wasn't enough to shoot Eric once or twice. He shot him eight times. Eighteen bullet holes where the bullets went in…and passed out…and back in again. The evidence of Daryl Atkins's crime is horrifying. It is vile.”8

The jury also heard from Nesbitt's friends and relatives. Nesbitt's coworkers recalled the squadron picnic the afternoon of the murder and remembered Nesbitt as being “light-hearted” and “fun-loving,” “a guy who liked to joke around,” and the “life of the party.” But now he was “gone.” Mark Armitage, an Air Force buddy who claimed to be Nesbitt's best friend, said he was devastated. “It hurt really bad. My wife was nine months pregnant and I had to tell her he was dead. She didn't stop crying for four days. She gave birth four days later. Eric was supposed to be my son's godfather.”

But the most wrenching testimony came from Nesbitt's mother, Mary Sloan, who told of the pride she had in her son, an Eagle scout who aspired to have a career in the Air Force. “I had a little counseling after Eric had died but it didn't seem to do any good. I just sat there and cried. I don't know how you can counsel for something like this.”

The jury recommended the death penalty for Atkins, and the presiding judge, Prentiss Smiley, agreed. In Virginia, as in most states, all death sentences go to the state supreme court for automatic review. The Virginia Supreme Court upheld the guilty verdict, but in an opinion by Justice Lawrence Koontz, it found a procedural flaw in the sentencing part of the trial. On retrial before an entirely different jury, the defense pressed its claim that Atkins should be spared because he was mentally retarded.

Virginia, like many states, left it to jurors to assess how mentally impaired a defendant may be and to weigh the testimony of competing forensic psychiatrists (and in this case psychologists) whose expertise far exceeds their own. The bible of the psychiatric community is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, published by the American Psychiatric Association. Version Four (DSM-IV) was in use at the time, which defined the essential feature of mental retardation as “significantly sub-average general intellectual functioning (Criterion A) that is accompanied by significant limitations in adaptive functioning in at least two of the following skill areas: communication, self-care, home living, social/interpersonal skills, use of community resources, self-direction, functional academic skills, work, leisure, health, and safety (Criterion B). The onset must occur before age 18 years (Criterion C).”

“Mild” mental retardation is typically used to describe people with an IQ level of 50–55 to approximately 70.9 Dr. Evan Nelson, a forensic psychologist, testified that Atkins's IQ was 59, suggesting a mental age of from nine to twelve. Atkins's “adaptive functioning” was quite awful. In addition to his various felonies, Atkins never held a job and was an abject failure in the Hampton public schools. He had failed the second grade. He had received failing grades in all his classes when in the eighth grade and had scored in the fifteenth percentile on standardized achievements tests. It was further downhill from there. When he reached the tenth grade, which he also failed, he scored in the sixth percentile. With a cumulative high school grade point average of 1.26 out of a possible 4.0, he dropped out of school. Nelson diagnosed Atkins as “mildly retarded” with an antisocial personality disorder.

The Commonwealth of Virginia countered with its own forensic psychologist, Dr. Stanton Samenow, who never administered any IQ tests to Atkins but interviewed him twice and concluded that he was not at all retarded. When Atkins's lawyer, George Rogers, asked, “Do you have an expert opinion as to the Defendant's intellect?” Samenow answered, “He is of average intelligence, at least.” When asked to explain how he came to this conclusion, Samenow said it was through “the vocabulary and syntax that he used in talking with me.” Samenow was also impressed that Atkins was able to name the governor of Virginia and knew that the son of former president John F. Kennedy had died in a plane crash.10

Whatever weight the jury applied to the defense's claims of mental retardation, it wasn't enough. After deliberating for thirteen hours, the jury recommended death and Judge Prentiss Smiley again complied. The Virginia Supreme Court affirmed the death sentence, rejecting a claim that sentencing a mentally retarded offender to death violates the Eighth Amendment prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment.

The Virginia Supreme Court decision could hardly have come as any surprise. On matters of federal constitutional law, state courts and lower federal courts are all bound by the interpretations of the U.S. Supreme Court. And the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled only seven years earlier, in 1989, that mental retardation was not an automatic bar to a death sentence, although it was a factor a jury could and should consider.11 That case involved Johnny Paul Penry, convicted of the brutal rape and murder of Pamela Mosely Carpenter, sister of the Washington Redskins’ star placekicker Mark Mosely. Although Penry was said to have had the mental age of only a seven year old, the Court ruled he could still be a candidate for the death penalty. The Court noted that the abilities of mentally retarded individuals vary and that many may still “act with the degree of culpability associated with the death penalty.” The Court also rejected the use of a presumed “mental age” as an excuse for criminal conduct, finding it susceptible to being feigned and inherently unreliable.12

Significantly, however, the Virginia Supreme Court was not unanimous; two justices dissented. Lawrence Koontz—the same judge who had written the earlier decision upholding Atkins's guilt—wrote a bold and passionate dissent that seemed to repudiate everything the U.S. Supreme Court had said in its Penry decision years earlier. “It is indefensible,” admonished Justice Koontz, “to conclude that individuals who are mentally retarded are not to some degree less culpable for their criminal acts. By definition, such individuals have substantial limitations not shared by the general population. A moral and civilized society diminishes itself if its system of justice does not afford recognition and consideration of those limitations in a meaningful way.”13

Justice Leroy Hassell joined Koontz's dissent but also wrote separately about the commonwealth's claim that Atkins was at least of average intelligence: “I simply place no credence whatsoever in Dr. Samenow's opinion that the defendant possesses at least average intelligence. I would hold that Dr. Samenow's opinion that the defendant possesses average intelligence is incredulous as a matter of law.” As you will see, the words Justices Koontz and Hassell chose would have a subsequent impact even they could not have foreseen.

Watching these proceedings carefully from the sidelines was a law professor in Albuquerque, New Mexico, named Jim Ellis. In addition to teaching constitutional law at the University of New Mexico Law School, Ellis had devoted most of his adult life to working on behalf of people with mental disabilities. A conscientious objector during the Vietnam War, Ellis agreed to alternate service as an orderly at the Yale Psychiatric Institute. The experience changed him forever. At the time, he was changing bedpans. But in the years that followed, he would be changing lives.14

After his time at the psychiatric institute, Ellis went to law school, became a lawyer, and channeled his skills to advance the cause of America's less fortunate. He rose to become the president of the American Association on Mental Retardation (AAMR); he had filed more than a dozen legal briefs on behalf of the association in various court cases, including one in the landmark case of Penry v. Lynaugh discussed earlier The decision against Penry was a huge disappointment for Ellis. At the time the Penry case was decided, only two of the thirty-eight states that authorized capital punishment had made an exception for offenders with mental disabilities—which was hardly a national consensus. Drawing on the Court's 1958 decision in Trop v. Dulles, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor wrote for the majority: “While a national consensus against execution of the mentally retarded may someday emerge reflecting the ‘evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society,’ there is insufficient evidence of such a consensus today.”15

Ellis took the Penry v. Lynaugh decision personally, and he personally traveled the country to change the legislative landscape, to create the national consensus that Justice O'Connor found lacking. He appeared before dozens of legislative committees arguing for the rights of people with disabilities. And it appeared to have worked. In the next thirteen years, another sixteen death-penalty states joined the ranks of Georgia and Maryland in prohibiting the execution of such individuals, in no small measure due to the efforts of Jim Ellis.

While Ellis was watching the Atkins case rebound up and down the courts of Virginia, the Virginia Resource Center, which was handling Atkins's defense, had its eyes on Ellis. And when the U.S. Supreme Court announced it would take up the Atkins case, the center tapped Ellis to argue it. It was a daring gamble. Ellis had never argued a court case in his life, not even for a traffic ticket. Now he would be in the highest court in the land arguing an issue that had, for decades, been the closest to his heart. It would be the challenge, and the opportunity, of a lifetime.

The Atkins case was now national news. The Supreme Court's argument, set for February 20, 2002, had drawn much more attention than either the trial or the crime itself. It was one of those special cases in which even a reporter regularly assigned to cover the Court had to make a reservation to be assured a seat.

As the Petitioner in the case challenging the Virginia Supreme Court's decision, Ellis was first up. He began by declaring, “the evidence is now clear that the American people in every region of the country have reached a consensus” against the execution of mentally retarded people.16

Less than a minute into his argument, Chief Justice William Rehnquist interrupted, “What is your definition of a consensus, Mr. Ellis?” Ellis replied: “It's when the American people have reached a settled judgment based on a—” Rehnquist again interrupted, “That's a perfectly sound phrase, but how do we go about figuring out when that occurs?” Defining just what constitutes a consensus would dominate most of the hour-long hearing.

Ellis emphasized how the number of death-penalty states prohibiting the death penalty for mentally retarded individuals had grown from only two in 1989 to eighteen in 2002. The question then arose how the Court is to count the twelve states that don't have capital punishment at all. If we were to add them in, we would have thirty states opposed to such executions. That would constitute a clear majority and further evidence of an evolving consensus.

At this point, Justice Antonin Scalia broke in, saying that “an evolving consensus isn't enough, you need a consensus.”

Rehnquist wanted to know how New Hampshire, where he maintained a summer home, might be counted. The New Hampshire death-penalty law allowed the execution of offenders with mental disabilities, but there hadn't been an execution in the state in sixty years.

Justice John Paul Stevens, one of the four dissenting justices in the Penry case and the only Penry dissenter still on the Court, was clearly sympathetic toward Ellis and tossed him a red-letter pitch: “Apart from the consensus arguments, what's really behind your position? What's wrong with executing the mentally retarded?” Ellis answered that “they lack the culpability, the blameworthiness…because they lack the full understanding of the consequences of their actions.” Justice David Souter interjected: “They know it's wrong, but they don't appreciate how wrong it is.” Ellis: “Yes.”

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg appeared frustrated that Ellis had failed to address another possible explanation—one Ellis had made in his written brief to the Court—as to why mentally impaired offenders should be spared death sentences. “Isn't it true, she asked, “that people in this class of diminished capacity will often respond inappropriately, such as smiling when they should be showing remorse,” making it all the more difficult for counsel to effectively represent them?

Ellis agreed, saying the phenomenon presented “a particularly and uncomfortably large possibility of wrongful conviction and thus wrongful execution.”

Justice Scalia, who clearly did not believe mentally retarded defendants were entitled to any blanket exception, asked Ellis why the defense can't simply explain the defendant's inappropriate conduct to the jury: “It seems to me…the more he'd smile, the more…the jury would say, ‘Boy, this—this person really shouldn't be executed. He's not playing with a full deck,’ or whatever.”

Ellis responded with what most criminal-defense lawyers know well. The mental-retardation defense is a double-edged sword. While research shows that mentally impaired individuals are less likely to resort to violence than those in the general population, some juries may be even more disposed to sentence a mentally impaired defendant to death, particularly one who, for whatever reason, might smile when charged with a horrible crime.

When Pamela Rumpz, the assistant attorney general representing the Commonwealth of Virginia, got up to speak, the argument returned to determining what constitutes a “consensus” and how trends of the past thirteen years might bear on the country's “evolving standards of decency.” What follows is a summary of the discussion in the Court.

The twelve states that don't even allow capital punishment are not part of the equation, insisted Rumpz. These states had not staked out any position on the mental-retardation issue, and if they were to subsequently change their laws to allow the death penalty, there would be no way of predicting whether mentally retarded offenders would be included.

Rumpz went on to argue that even the eighteen states that Atkins's lawyers said had created a consensus have not entirely abandoned the death penalty for impaired offenders. New York, for example, will still allow the execution of an impaired inmate who commits murder while in prison. And several of the eighteen states do not apply the exception retroactively to offenders sentenced before the changes in the state's laws took place. And even if you do count all eighteen states, pressed Rumpz, that isn't a majority given that twenty other death-penalty states have no such exceptions. If there is any consensus, continued Rumpz, it is to allow the juries to decide.

By now, the U.S. Supreme Court had spent nearly thirty years refining death-penalty procedures. The justices’ best efforts, however, left some potholes to traverse in succeeding cases. One of them came up in the Atkins arguments. In Gregg v. Georgia, the court insisted that defendants on trial for their lives be given careful, individualized consideration, taking into account “their character and record.” That command was central to Rumpz's argument: “What is at stake here is this Court's long-established jurisprudence of individualized sentencing in matters of the death penalty. Atkins would have this Court remove from individualized sentencing one whole group of people based upon one mere factor, and that is their alleged mental retardation.”

As she pressed the point that a defendant's mental disability is exclusively a matter for the jury, Rumpz found herself wading into treacherous waters. Justice Anthony Kennedy, who has an uncanny talent of being on the winning side in close cases, asked, “So any person who has criminal responsibility can be executed, no matter how retarded they are? That's your position?” Rumpz: “That is the position of the Commonwealth of Virginia, yes.” Justice Scalia threw Rumpz a lifeline: “You would not say ‘no matter how retarded,’ I mean, presumably, there's some point at which the retardation is so severe that the person does not comprehend what he's doing.” Rumpz, reversing ground: “Exactly, Your Honor.”

Rumpz's point seemed to be that the state would still have to prove the act was deliberate and carried out with premeditation; after that, anyone would be eligible for society's ultimate sanction. Justice Souter asked how that rationale might be applied to children: “Let's take five year olds. Would you argue that five year olds should be executed if they deliberated on the act and the state can otherwise prove the mental element?” Rumpz responded: “I think that's unlikely to happen, but if a person can deliberate and premeditate, and if a person can commit a brutal, calculated, premeditated murder, and if a person is found competent at the time he commits that murder, and competent to assist his lawyers at the time of the trial, then we're not looking at somebody whose culpability is any less than yours or mine.”

The hour-long argument ended with no clear winner. And at no time during the hearing did the actual crime that led to this high-stakes court case ever come up; the name Eric Nesbitt was not uttered a single time.

The case was argued on a Wednesday, so if the Court followed its usual practice, the first tentative vote would have been the following Friday—only two days later. While that tentative vote rarely changes, it still took the justices a full four months to get their decision out. On June 20, 2002, the Court announced its long-awaited ruling. The justices had voted 6–3 to throw out Atkins's death sentence and put an end to the execution of anyone who met their state's definition of mental incapacity.17

The decision of the Court was announced by Justice John Paul Stevens, who, after laying out the facts of the case, quoted at length from the dissenting opinions of Justices Koontz and Hassell on the Virginia Supreme Court. “Because of the gravity of the concerns expressed by the dissenters,” wrote Stevens, “and in light of the dramatic shift in the state legislative landscape that has occurred in the past 13 years, we granted certiorari to revisit the issue that we first addressed in the Penry case.”

The Court's majority concluded that executing mentally retarded offenders would serve neither of the two accepted social purposes of the death penalty identified in Gregg v. Georgia, that is, retribution and deterrence. “Unless the imposition of the death penalty on a mentally retarded person measurably contributes to one or both of these goals,” wrote Stevens, it “‘is nothing more than the purposeless and needless imposition of pain and suffering,’ and hence an unconstitutional punishment.”18

The Court reasoned that because those who are mentally impaired have a diminished understanding of the consequences of their actions, they are more likely to act on impulse and are generally incapable of the same premeditation and deliberation as those who are not so afflicted, that they are less culpable and less deserving of the retribution of death. And, for the same reasons, they are also less likely to be deterred by the threat of a death sentence.

The justices also relied on polling data, which Stevens said “shows a widespread consensus among Americans, even those who support the death penalty, that executing the mentally retarded is wrong. Although these factors are by no means dispositive, their consistency with the legislative evidence lends further support to our conclusion that there is a consensus among those who have addressed the issue.”19

The decision drew a withering dissent from Justice Scalia, who seemed to pick up where the prosecutor left off with dramatic oratory in her closing argument. “Atkins ordered Nesbitt out of the vehicle and, after he had taken only a few steps, shot him one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight times in the thorax, chest, abdomen, arms, and legs.”

Scalia is a thoughtful justice and a good writer, but he is at his combative and uninhibited best when he writes dissents, which, unlike opinions for the Court, do not need the vote of any other justice. He has been a particularly forceful critic of the Court's death-penalty decisions and his dissent in the Atkins case was no exception:

Today's decision is the pinnacle of our Eighth Amendment death-is-different jurisprudence. Not only does it, like all of that jurisprudence, find no support in the text or history of the Eighth Amendment; it does not even have support in current social attitudes regarding the conditions that render an otherwise just death penalty inappropriate. Seldom has an opinion of this Court rested so obviously upon nothing but the personal views of its members.20 (italics in the original)

But it was not so much the Court's setting aside Atkins's death sentence that set the Justice off as it was the rationale behind the decision, that the sentence went against “the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.” Scalia has long argued that Trop v. Dulles was wrongly decided and that evolution in the Constitution can only be through a constitutional amendment. That is, the words of the Eighth Amendment mean what they say and cannot be changed in any way other than by the rigorous process of amending the Constitution.

Scalia had written previously that “the risk of assessing evolving standards is that it is all too easy to believe that evolution has culminated in one's own views,”21 precisely what he claimed the Court's majority had now done in the Atkins case. He accused the Court's majority of using a “fudged” and “contrived” consensus to reinterpret the meaning of the words “cruel and unusual” in order to impose its own view of what is right for America, adding, “The arrogance of this assumption of power takes one's breath away.”22

In his opinion and during the oral argument, Scalia did acknowledge that there is some point at which the Court might draw a line on the mental state of a defendant who might be sentenced to death. At the time the Bill of Rights was ratified, observed Scalia, the severely or profoundly retarded would not face execution. But in 1791, it would have been up to the jury to determine how Atkins, who was mildly retarded at worst, should be punished. Given that the words of the Eighth Amendment are precisely the same today as they were then, contended Scalia, the Court does not have the prerogative to take that authority away.

As you have seen in previous chapters and will see in subsequent chapters, this approach to the Constitution has had Scalia voting to uphold death sentences where a majority of his colleagues would not. It has also worked to the benefit of criminal defendants in some noncapital cases. His literal interpretation of the Sixth Amendment is just as strong as it is of the Eighth Amendment. And Scalia has shown no hesitation to set aside the convictions of other murderers,23 drug dealers,24 and child molesters25 where it has been shown that they have been denied the right to confront the witnesses against them face-to-face in court, as the Confrontation Clause of the Sixth Amendment requires.

While the Court declined to ban the execution of mentally impaired offenders in 1989 and imposed just such a ban in 2002, it didn't technically overrule itself. The test the Court applied in each case was the same: whether the practice was consistent with the country's evolving standards of decency. Only the facts had changed from one case to another, with the Court finding a consensus in 2002 that it did not perceive in 1989.

And while the majority did throw out Atkins's death sentence, they left open the possibility that he could still be executed. You will recall there was a difference of opinion during the trial as to whether Atkins was in fact mentally disabled, the forensic psychologist for the defense insisting that he was, but the forensic psychologist for the state insisting that he wasn't. The U.S. Supreme Court did not weigh in on this question but rather remanded the case back to the Virginia courts, where it continued to take some odd, if not bizarre, twists and turns.

The Virginia Supreme Court ordered the Circuit Court for York County to empanel another new jury and conduct yet another sentencing hearing, the third such hearing. It did so, and the new jury concluded that Atkins was not mentally retarded under Virginia law and once again recommended he be put to death. After three trials that produced a cumulative vote of thirty-six to nothing in favor of executing Atkins, Judge Prentiss Smiley again dutifully followed the jury's recommendation. And as Atkins was being led from the courtroom, he fulfilled Justice Ginsburg's apprehensions about mentally impaired defendants by flashing a broad smile and a peace sign to his family in the spectators’ gallery. Atkins appeared to be the only person in the courtroom quite unfazed by the outcome.

The case, however, wasn't over yet. Attorneys for Atkins again appealed to the Virginia Supreme Court citing thirty-seven errors in the latest sentencing proceeding, most of which went nowhere. But the Court did find two of the alleged errors persuasive. The Court agreed with the defense that one of the state's witnesses should not have been allowed to testify as a so-called expert. The Court also ruled that prosecutors should not have told the new jury that a previous jury had already sentenced Atkins to death and that doing so was unduly prejudicial. The Court ordered the Circuit Court to try again with yet another, fourth jury, solely to determine whether Atkins was mentally impaired under Virginia law.

What followed was a twist that no one could have anticipated. One of the central issues during the initial trial back in 1998 was who had actually shot Eric Nesbitt. Was it Daryl Atkins? Or was it his codefendant, William Jones? Each had accused the other, and Jones had agreed to testify against Atkins in exchange for a life sentence.

In preparing Jones for his courtroom testimony back in 1998, prosecutors had questioned him for two hours about what he was going to say, which is not at all an unusual practice. The session was tape-recorded. But when Jones's story became what prosecutors later described as “problematic,” they shut off the tape recorder. Some of what Jones was saying was inconsistent with the forensic evidence. While the recorder was off, prosecutors staged a reenactment of the crime to help Jones get his story straight. And when they turned the recorder back on sixteen minutes later, Jones's story had changed somewhat.

The defense never learned about the unrecorded break in the interview until Jones's lawyers came forward with the story many years later. Atkins's lawyers seized the new information to accuse prosecutors of suborning perjury in the coaching of their witness and of failing to disclose to the defense Jones's uncertainty, in violation of Brady v. Maryland, the landmark 1963 decision requiring prosecutors to turn over all relevant exculpatory evidence.26 After all of this, could it be that they had the wrong man? Was it possible that Jones was the killer and not Atkins after all?

Probably not. The chief investigator for the case, Troy Lyons, who attended Jones's interview and operated the recorder, told the authors that the change was insignificant, that Jones was merely confused, that he got mixed up over such matters as to whether the gun was in Atkins's left hand or right hand.27 But Judge Prentiss Smiley saw that mix-up as significant, believing it might cast doubt on Jones's credibility, that it might provide just enough doubt in the jury's mind about who pulled the trigger to make a death sentence inappropriate. Judge Smiley had already sentenced Atkins to death three times. He had had enough. Following two days of hearings, he commuted Atkins's sentence to life in prison.

This time, it was the Commonwealth of Virginia who appealed to the state supreme court arguing, among other things, that Judge Smiley had been directed only to determine whether Atkins was so mentally impaired that his execution could not proceed under the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in his case. Throwing out the death sentence on unrelated grounds, the commonwealth argued, exceeded his authority. Dividing 4–3, the Virginia Supreme Court disagreed and upheld Judge Smiley.28 The decision was announced by Justice Leroy Hassell, the same justice who felt early on that Atkins was not an appropriate candidate for the death penalty and who had dissented so passionately from the Virginia Supreme Court's initial decision holding otherwise.

Ten years after the trial and seven years after the Supreme Court's precedent-setting decision in the now-famous case of Atkins v. Virginia, it was finally over. And despite all the wrangling over the punishment for mentally retarded defendants, Atkins's own punishment wound up turning on a completely unrelated matter.

Atkins is now serving out his life sentence at the Wallens Ridge State Prison in Big Stone Gap, Virginia. Jones is serving his life term at the Nottoway Correctional Center near Burkeville, Virginia. Under Virginia law, neither will ever be eligible for parole.

Judge Prentiss Smiley never did learn how his case ended. He passed away after a long bout with cancer, two months before the Virginia Supreme Court affirmed his decision to commute Atkins's death sentence to life in prison.

In a recent interview with the authors, Eric Nesbitt's mother, Mary Sloan, expressed neither anger nor indignation at the case's outcome. But Sloan told us she believed “Atkins knew what he was doing. I felt the jury did a good job. It was an intelligent, well-picked jury and they [the courts] should have listened to them. We miss Eric. He's still a member of the family, even though he's not here.” And she added, she has adapted to the loss: “You have to adapt. You have no choice. You can't let someone like Daryl Atkins take your life away.”29

The Virginia State Bar dismissed misconduct charges against commonwealth attorney Eileen Addison for her handling of the Atkins prosecution. In August 2011, however, Addison was cited for misconduct for withholding exculpatory evidence in another, unrelated murder case.30 Two weeks later, she lost her bid for reelection in the Republican primary election, defeated by a former deputy.

Jim Ellis, who played such a large part in turning the country around along with the Supreme Court, continues to be a very popular law professor at the University of New Mexico Law School. Following his landmark Supreme Court victory, the American Bar Association presented Ellis with its prestigious Paul Hearne Award for Disability Advocacy. He received the Champion of Justice Award from the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. And, although he had only one actual court appearance under his belt, the National Law Journal, one of the country's most respected legal periodicals, named Ellis its 2002 Lawyer of the Year.