The question before the Court today is whether or not the State of Louisiana may, for the sole purpose of executing an inmate, forcibly medicate a mentally ill inmate with psychotropic drugs.

—Keith B. Nordyre, arguing Louisiana v. Perry before the U.S. Supreme Court on October 2, 1990

In 1983, singer Olivia Newton-John, then thirty-five years old, was riding a huge crest of popularity following a successful world tour. Newton-John's “Physical Live” tour had begun the previous year and had brought her renewed fame and more fortune—as well as a determined stalker named Michael Perry. Times were desperate enough for her to call upon a private security service for help.

“[Perry] developed an obsession involving my client's eyes and was convinced they had changed colors as a signal to him,” said Gavin de Becker, head of the security service Newton-John hired. Perry, an escapee from a mental institution, camped out near Newton-John's Malibu home and sent her letters saying he wanted to prove to himself she was “real,” rather than a “Disneyland mirror image.”1 Perry came from a small Louisiana town some forty miles from the Gulf Coast and had written her, “The voices I hear tell me that you are locked up beneath this town of Lake Arthur and were really a muse who was granted everlasting life.”2

“Somehow he convinced himself that she was responsible for dead bodies rising through the floor of his home,” de Becker said. His firm's employees turned Perry away from Newton-John's estate twice. Perry eventually returned to Louisiana, where his fantasies escalated into violence.3

Perry's hometown of Lake Arthur was a sleepy community of about 3,500 people in 1983, though economic changes have since shrunk the population to about 3,000. The principal sources of livelihood were family farms and the oil fields—Louisiana's first producing well was drilled fewer than twenty miles away, in Evangeline, at the turn of the century. Whether you approached from the north on Highway 26 or from the south on Highway 14, you were greeted by a roadside sign announcing, “Lake Arthur—A Good Place to Live.”4 The biggest attraction in town was the high school football team, the Tigers.

While in school, Michael Perry was lead trumpet in the band that played at the Tigers’ home games. Pookie Marceaux, who lived across the street and was a year behind him at school, said Michael was a good student—“His IQ was higher than some bowler's average”—and he was more inclined to books than athletics.5

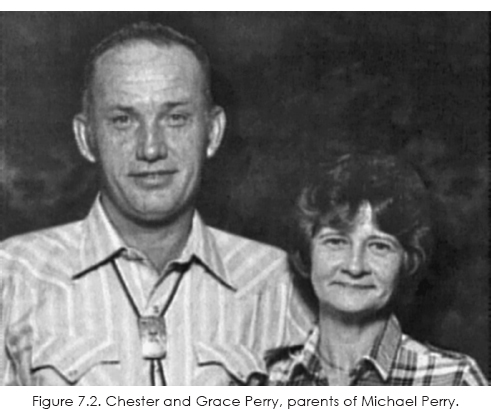

Perry's father worked on oil rigs; his mother was a “tireless homemaker,” said Marceaux, “with a warm smile, a generous box of spattered recipe cards, and a talent for making them a reality.” Michael was the middle child of three in a church-going family.

Marceaux said Perry seemed to lose his way after graduation; he was accident prone and kept getting into minor scrapes with the law. “He constantly attracted attention to himself by doing weird things,” said Marceaux.6 But Marceaux and the entire community were shocked to the core by the way Perry imploded after his return from one of his California stalking trips in the summer of 1983.

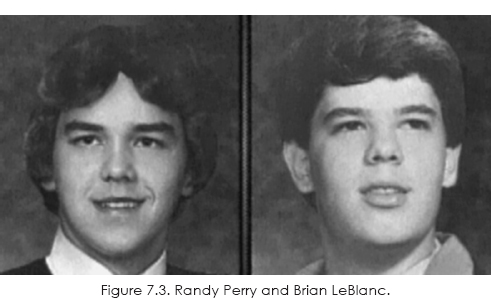

On the afternoon of July 17, armed with a 16-gauge shotgun, a 12-gauge shotgun, a .357 Magnum, and a Beretta pistol, Perry set off on a shooting spree in which he killed his parents and three other relatives. The victims were Chester Perry, forty-eight; Grace Perry, forty-seven; cousins Randy Perry, nineteen, and Brian LeBlanc, twenty-two; and his nephew Anthony “Tony” Bonin—just two years old. Perry shot his parents through the eyes.

Perry confessed the murders to his uncle and aunt after he was taken into custody several weeks after the murder. “He told me the scene was like a battle in Vietnam…because there was blood everywhere,” Zula Lyon, Grace Perry's sister, would later testify. “He said not to worry about it, those people meant nothing to him,” she said.7

“I killed the five people,” Perry told Jefferson Davis Parish jailers Herbert Durkes Jr. and Robert Lee. Durkes testified that Perry asked to see the two jailers because he wanted to confess. It was an unusual request, but Perry refused their suggestion that he talk to police detectives instead. Durkes and Lee went to his cell and squatted down in the corridor so they could talk through the small opening in the cell's steel door normally used to pass food. From that position, they were each able to see Perry's head and shoulders and watch his facial expressions.8

Durkes read Perry his Miranda rights, and Perry said he understood them. Durkes asked if Perry wanted a lawyer present; Perry said, “No.” The surreal preliminaries out of the way, the two jail guards listened intently as Michael Perry recounted his shooting rampage. He first shot his two cousins with a pistol, Perry told the two jailers, then finished them off with the 16-gauge shotgun. Then he crossed the yard to his parents’ empty home and broke in. His mother and father were expected back shortly from an out-of-town trip with their young grandson, Tony. While he waited, Perry passed the time by listening to music.

When his parents arrived home, “I blew my father's brains out,” Perry said. He told the jailers he then walked up to his mother with a pistol and “shot her head off.”9

Durkes said he asked Perry why he killed the child and quoted Perry as saying, “I had to be sure the little witch was dead. The kid was evil, some sort of a devil, a witch.” Durkes said Perry told him that the Bonin child “was a very smart kid, too smart for his age.”10

Following the murders, Perry removed $3,000 from his father's wallet, took his parents’ car, and drove more than 1,200 miles to Washington, DC, where he registered at a motel near the Supreme Court. The proximity of the Court would take on new relevance later, when investigators unearthed an additional list of Perry's potential new victims.

Two weeks after his arrival, Perry was accused of stealing a radio from another motel guest. Metropolitan police officers who responded to the complaint ran a routine check of Perry's name, turning up five murder warrants from Louisiana.

After his arrest and return to Louisiana, Perry told authorities where to find two of the guns, which he had dumped into a canal. The admission took place as Sheriff Dallas Cormier and Deputy Ervin Trahan were driving Perry to a psychiatric evaluation at the Feliciana Forensics Facility, 130 miles away in Jackson, Louisiana. His lawyers would later argue that the statement was inadmissible because of their client's mental condition. The Louisiana Supreme Court ruling on that issue was explicit and in keeping with the odd nature of the case:

Even were we to agree with this medical conclusion, the diagnosing doctors testified defendant lost contact with reality when the trigger words, “Olivia Newton-John,” were used. Otherwise, defendant remained in contact with reality. We note Deputy Trahan testified those trigger words were not brought up during the trip to Feliciana.11

The peculiarities of Perry v. Louisiana would continue to unravel. Perry initially confessed to the murders and then recanted. He pleaded innocent by reason of insanity, then dropped that plea over the objections of his lawyers, entering a simple “Not guilty.” “He told me, ‘I killed those people, but the judge doesn't want me to plead guilty because the case is so serious,’” one of Perry's aunts, Zula Lyon, testified. Perry's delusions and disorientation spilled over into the courtroom.

Although a team of psychiatrists had found Perry competent to stand trial and to assist in his own defense, Perry's demeanor was erratic.12 During his preliminary hearing, Perry interrupted witnesses, spit from the defense table, gestured to relatives, and stuck out his tongue at them.13

As his jury was being selected, Perry loudly challenged one prospect who stated he preferred life imprisonment as the punishment for murder. “Sir, are you aware that people get killed in a penitentiary?” Perry called out. Judge Cecil Cutrer told Perry to stop talking. “It's my life, it's my life,” Perry replied. “I'll protect it the best I can. Now shut up,” Cutrer said.

Perry recognized the mother of one of the victims in the courtroom, and he repeatedly gestured at her and made faces until the woman left the room in tears. He removed his shoes and socks while seated at the defense table, and he tied a string and rubber bands around his toes. He also wrapped a white bandanna around his head.

During a break in proceedings, Perry told a television reporter he was doing these things because “it's the lifestyle of the Mafia. You got to keep moving.” He also told the reporter that he was arrested by “a top-secret agent,” and that if the state didn't kill him in the electric chair, then he would be killed in prison. “You remember that; you remember that,” Perry told the reporter.14

By contrast, Perry showed no emotion during testimony or the introduction of exhibits that elicited gasps and expressions of shock from others in the courtroom. Among the exhibits shown to the jury were a bloodstained sofa cushion where cousin Randy Perry's body was found; a bloody, light-blue pillowcase with hair and skull fragments from cousin Brian LeBlanc; an almost completely bloodstained printed pillowcase; and a stained sheet and pink bedspread also from LeBlanc's bed. Some jurors blanched, but Perry did not visibly react.15

Although they had been warned that the photographs would be explicit and gruesome, many of the jurors appeared shaken when they viewed the pictures; several of them openly wept. The pictures, visible at times from the audience, showed the victims and the locations where they were discovered. Large pools of dried blood surrounded the bodies of two-year-old Tony and Michael's mother, Grace Perry. The photos of these two victims appeared to be especially disturbing to the jurors.16

After six days of testimony, Assistant Attorney General Rene Saloman used photographs again in summing up the prosecution's case. He showed the jury pictures of the victims alive and well, then as they appeared after being shotgunned to death. Saloman said they died “by hatred, by design, by purpose of mind.”17

“If you should ever say a prayer, say it for each one of these victims,” the prosecutor said. “If you should ever shed a tear, shed it for these victims. Michael Perry killed out of hate, greed and avarice to put them out of his way.”

Defense Attorney Mark Romero cited “shoddy” police work in his closing argument, saying there were serious flaws in the state's case, especially concerning Perry's alleged confessions, that presented the jury with reasonable doubt. “There's too much doubt, too much doubt,” he said. The jury apparently had few doubts. After just one hour of deliberation—an hour Michael Perry spent eating lunch in his cell—the panel of nine men and three women found him guilty of five counts of first-degree murder. Perry heard the verdict impassively; the mother and grandmother of victim Randy Perry clutched shaking hands as it was read, then collapsed into each other's arms.

Under Louisiana law at the time, it was the jury's obligation to decide on a sentence of life or death; its recommendation would be binding on the judge. In the penalty phase of the trial, conducted on the same Halloween afternoon on which the original verdict was delivered, the defense called two doctors who had examined Perry after his arrest. Dr. Louis Shirley, a family practitioner who was the first to see him in jail, said Perry showed “definite signs of schizophrenia, paranoia” and that he recommended Perry for further evaluation. Dr. Harold Sabatier, a veteran of Louisiana sanity commissions, said his later diagnosis was “chronic schizophrenia.”

Dr. Sabatier testified that schizophrenic tendencies had been diagnosed in Perry's family—the defense indicated that a sister, cousins, aunts, and uncles suffered from mental illness—and that schizophrenic tendencies can be genetic. He said Perry might not have been able to resist the “inner voices” commanding him to commit violent acts. Dr. Sabatier said that a paranoid person had the capacity to plan a crime, such as the ambush of Perry's parents, “ingeniously, and wait for them with unlimited patience.”18

Defense Attorney Romero told the jury that Perry was suffering from mental problems when he committed the five murders and “he's still suffering from mental problems.” “You've seen the way he looks, the way he's acted, what he's done,” Romero told the jury, referring to his client's erratic actions in the courtroom. He asked for a sentence of life without parole, saying, “I don't think taking one life will bring back five other lives.”

Arguing for the death penalty, Assistant Prosecutor Steve Laiche said Perry deserved no mercy. “Where was that mercy for the victims?” he asked. “We should say to Michael Perry that life is precious to us, and if you violate the law, then you have to pay the penalty.”

That's what the jury said. It took them twice as long as the original verdict, almost two hours this time, to decide that Perry had committed the murders “with an intent to inflict great bodily harm,” and in an “especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel manner”—two elements required to return a death sentence and reserve Perry a seat in Louisiana's electric chair.19

As the clerk read the verdict, Perry cupped his hand under his chin, his elbow pressing against the defense table, his face showing no visible emotion. Randy Perry's mother, Gwen Walker, jumped up and wrapped her arms around prosecutor Rene Saloman to thank him for his role in convicting her son's killer.

“The chair is too good for him,” Mrs. Walker told reporters moments later. She held her mother's arm as they stood on the courthouse steps in a chilly breeze, her hands quivering and tears streaming down her face. “It's not going to bring Randy back, or any of them back, but he thought he could get away with it,” she said. “He should be killed just like he killed all of them.”20

Death verdicts in Louisiana are automatically appealed to the state supreme court, which, a year after the trial, unanimously upheld Perry's conviction. The court noted that although Perry had “a history of emotional or mental disorders” predating the murders, three physicians making up a court-appointed sanity commission “were unanimous in their conclusions that the defendant was able to proceed with trial.”21

Perry had killed the victims “in a violent, bloody encounter which was deliberately planned,” wrote Associate Justice Luther F. Cole for the court. “The death penalty in such a case is proportionate to the offenses and to this particular defendant.”22 The Louisiana Supreme Court ruling was definitive in its appraisal of Perry's sanity through the time of his trial, but it left a legal door open to the defense on the issue of the condemned man's state of mind following the jury's verdict. If Perry had become insane after his trial, the court indicated, and no longer understood the death penalty or that it was a punishment for his crime, he might not be competent enough to be executed. In the words of the ruling, “The State will not impose the death penalty on Michael Owen Perry if a court determines he has become insane subsequent to his conviction.”23

The court practically invited Perry's lawyers to seek another sanity hearing. Judge L. J. Hymel, who had inherited the case from Judge Cutrer, granted a new sanity hearing in April of 1988, at which he had a question for the defendant: “What do you want me to do for you, Michael?” Replied Perry: “Well, I know you're the most fierce judge in the world and the whole world knows it…. I want to be found innocent and give me all the money in the world.”

In frequently rambling testimony, Perry said, “I did it. I was tattooed. I was paid $9 million. I did it for you.” Perry also told the court, “I was God when I was 7 years old. And I'm innocent. I didn't do it.” But in response to questions, Perry said he knew the location of the electric chair, the State Penitentiary at Angola, and that it killed people “dead like a doornail, the end of the world.” These statements seemed to indicate that Perry understood the death penalty and its punishment.

Three psychiatrists and a psychologist testified that Perry suffered from psychotic and paranoid delusions, showed a loose association with reality, and was “a moving target” when it came to competency. “He's not in the same place all the time,” Dr. Aris Cox testified. “Sometimes he is competent, sometimes he's not.”24

As Dr. Cox told us in an interview for ABC's World News Tonight, “When he's been off medication, I have him tell me he does not believe that the process of electrocution will kill him. He has a lot of ideas that he's some sort of religious figure who's immortal.”25

At the trial, the experts agreed that Perry's condition improved with medication—and they said that was their dilemma. “I certainly have problems with giving someone medication so that they can get better and be executed,” Dr. Cox told the judge.

That was the central issue: Was it legal for Perry to be medicated against his will to make him well enough to be electrocuted? Judge Hymel said yes, and the Louisiana Supreme Court agreed. Michael Perry's fate would now depend upon an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Court had already refused to consider an appeal filed by Perry's lawyers in 1987. No reason for that rejection was cited. But this latest appeal raised an issue that apparently intrigued the justices.

The justices of the Supreme Court had decided in 1986 that prisoners could not be executed while insane. The case of Ford v. Wainright involved a murderer who was apparently both sane and competent when he was tried in Florida and sentenced to death for killing a police officer during a restaurant robbery. But Alvin Bernard Ford deteriorated on death row: he began hearing voices and suffering delusions; he became convinced he was “Pope John Paul III.” A panel of three psychiatrists appointed by the governor could not agree on a diagnosis, but they did agree that Ford understood why the death penalty had been imposed and what it meant. That was enough for Governor Bob Graham. He signed the death warrant.

Ford was within fourteen hours of execution in December of 1981 when a federal appeals court granted a stay, starting his case on the long road to the U.S. Supreme Court. The justices heard the case on April 22, 1986, and Ford's lawyers made two arguments: that there was a common law tradition, dating back to the thirteenth century, prohibiting the execution of the insane; and that Florida had no clearly established procedures for determining the sanity of the condemned.

In death penalty appeals, lawyers generally keep their clients away from the press, concerned about negative images. Ford's defense team used a reverse strategy: they had him hold a press conference so that everyone could see how unbalanced he was. The strategy worked; the hoped-for negative image reverberated from coast to coast.

|

For a video report on the Ford arguments before the Supreme Court, go to: http://murderatthesupremecourt.com/ford |

The Court agreed with the Ford team's arguments, ruling 5–4 that states may not execute prisoners who have become insane and that only an independent panel of doctors or a court may decide questions of sanity.26 There were two further, unusual twists to the Ford case, one of them tragic. In 1989, a federal judge ruled that Ford had become sane and was eligible for execution. Ford's lawyers launched an appeal, but before the case could be heard, Alvin Ford was found unconscious in his cell on Florida's death row. He died two days later at the age of thirty-seven; the death was determined to be from natural causes.

The Supreme Court dealt with the issue of forced medication in 1992 when it ruled in favor of David Riggins, a Nevada prisoner who had been given antipsychotic drugs against his will in order to make him competent to stand trial for murder. Riggins was convicted, but the Court set the conviction aside, ruling that his Sixth Amendment right to a fair trial had been violated by the forceful administration of the drugs before and during his trial.27 The legal stage was set for the Perry appeal. The Supreme Court had resolved the issues of executing the insane and of medicating the insane before trial. But the issue of “forced sanity” to enable an execution was novel enough that the Court agreed to hear Perry's case. And even as lawyers for the opposing sides prepared their arguments, the question spurred furious debate outside the legal community.

Many doctors were particularly incensed. Relations between the medical community and the officials charged with carrying out executions had long been strained: physicians and other medical practitioners felt barred by the canons of their profession from taking an active part in executions. Doctors would agree to pronounce death, but not to assist in it. Medical professionals might help a condemned person prepare for an execution, even to the extent of prescribing tranquilizers, but they drew the line at helping executioners inject lethal chemicals. Now they were being asked to make mentally ill prisoners well enough so that they could be put to death; for many, there was no way to reconcile such treatment with their Hippocratic commitment to “do no harm.”28

“If Michael Owen Perry takes anti-psychotic drugs, he may no longer imagine Olivia Newton-John is a Greek demigoddess beneath a lake,” began an editorial in U.S.A Today, “but then Michael Owen Perry will be put to death.” Medicating Perry in order to execute him was “an insane idea,” the newspaper said. “You cure people to help them, not to kill them. To do otherwise replaces justice with vindictiveness.”29

That editorial stirred up so much reaction that two days later, the paper ran a slew of Letters to the Editor containing such opposing comments as:

—“I think insane inmates should be cured so they can be executed. There are enough murderers in this world.” (Springfield, Missouri)

—“They should be brought to a clarified state of mind, then executed…. Through various psychotropic medications, their level of consciousness may be raised so they can realize the consequences of their action.” (Beaumont, Texas)

—“I think they should be executed whether they're sane or insane. If they're sane enough to obtain a weapon and ammunition and drive down to someone's house and take their life, then they're eligible.” (Crossville, Tennessee)30

A St. Louis Post-Dispatch editorial bore the mocking headline “First Cure Him; Then Kill Him.” “If it weren't true,” the editorial read, “the latest capital punishment case before the U.S. Supreme Court would sound like some kind of sick joke.”31

The pro-execution argument was perhaps most trenchantly summed up by Linda Chavez, a former Reagan administration official writing as a syndicated columnist: “Justice would not be served by allowing a man who has slaughtered five members of his own family to avoid a lawfully imposed punishment. Perry should take his medicine.”32

“The question before the Court today is whether or not the State of Louisiana may, for the sole purpose of executing an inmate, forcibly medicate a mentally ill inmate with psychotropic drugs,” Defense Attorney Keith Nordyke said on the morning of October 2, 1990, setting the stage for his life-or-death argument before the Supreme Court. He argued that involuntary medication of Perry would be a violation of the Eighth Amendment's prohibition against “cruel and unusual punishment,” and it would also violate Perry's Fourteenth Amendment guarantee to “due process under the law.”33

Appearing against Nordyke and speaking from the same lectern in the Court's splendid chamber, Louisiana's assistant attorney general Rene Salomon responded: “We submit that if Louisiana can establish competency for a defendant to go to trial when that individual's presumption of innocence and other rights are at its zenith, then the State of Louisiana should be allowed to establish competency in order to carry out its sentence in this particular case.” It was reasonable, he argued, for the state to require medication that produced sanity for both trial and execution.

In questioning Nordyke, Justice Antonin Scalia noted that people lose many ordinary rights when convicted of crimes and that they also lose the “luxury” of many choices, including medical choices. “I guess the issue is whether someone who's been condemned to death,” asked Scalia, “continues to have that luxury?”

Before Nordyke could answer, Justice John Paul Stevens interrupted, asking the defense lawyer, “Do you agree that's a luxury?”

“Do I agree it's a luxury to be able to refuse medication?” responded Nordyke. “No, Your Honor, I believe it's an absolute, fundamental right that bottoms out in human decency.”

At one point, Salomon referred to the medication as “treatment,” and Justice Thurgood Marshall interrupted to ask, “But the primary purpose is to kill him?”

“I would say, yes sir, that's correct,” Salomon replied. “It is basically to execute him, in this case because the State has an interest.”

Later in the argument, as Salomon continued to press the state's right to inject Perry with psychotropic drugs, Marshall again interrupted to ask sarcastically, “Well, if all you say is true in the interest of Louisiana, while you're giving him the injection, why don't you give him enough to kill him then? It would be cheaper for the State.”

The arguments lasted fifty-five minutes, after which Chief Justice William Rehnquist thanked the lawyers and routinely announced, “The case is now submitted.” With those words, he effectively drew the curtain over a legal mystery that persists to this day.

The Supreme Court never decided the thorny question that prompted it to accept the Perry case for review; that is, whether a condemned prisoner could be forced to accept medication that would restore his sanity to the point where the state could execute him. The Court did spare Perry's life, but it punted. The constitutional issue would live to be fought another day.

Rather than issue a ruling in the case, the justices issued an unsigned order directing the Louisiana courts to reconsider the mandate that Perry be medicated. The Supreme Court said it wanted Louisiana to look at the issue again, in light of a case that it had decided before it even accepted the Perry case for argument. In that case, Washington v. Harper, the Court found that inmates had a limited right to refuse unwanted drugs.

It was a puzzling dismissal of the Perry issue. First, the Harper case was not a death-penalty case; Walter Harper was a disturbed prisoner serving a long sentence for robbery in Washington State. He was manic-depressive and prone to violence, but he felt he had a legal right to refuse psychotropic medication. Second, Harper provided no clear-cut guidance to the Louisiana courts.

In Harper, all nine justices agreed that the Fourteenth Amendment's guarantee of due process gives inmates what the justices called “a significant liberty interest” in avoiding unwanted mind-altering medication. But by a 6–3 vote, the Court ruled that a state can nonetheless “treat a prison inmate who has a serious mental illness with anti-psychotic drugs against his will, if the inmate is dangerous to himself or others and the treatment is in the inmate's medical interest.”

Why did the Supreme Court avoid the issue it had committed itself to resolve by accepting Perry? An empty seat on its bench at the time might provide a clue. Justice William Brennan had retired from the Court after thirty-four years, and his replacement, David Souter, was awaiting Senate confirmation when the Perry case was argued. He did not participate in the deliberations, and it is conceivable that the Court's remaining justices could have cast a tie vote of 4–4 in Conference. As the knowledgeable court observer Linda Greenhouse noted in the New York Times, a tie would have upheld the Louisiana Supreme Court decision that Michael Perry be medicated and executed; remanding the case to the state court for reconsideration on the basis of Harper, instead, insured that both Perry and the constitutional issue would survive the justices’ order.34

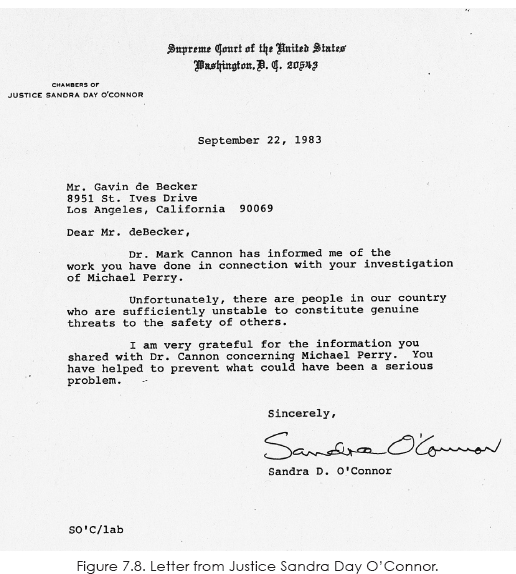

There is another eerie ingredient to this Supreme Court mystery. Michael Perry was arrested in Washington, DC, just a mile from the Court's steps. And at the scene of his murders, investigators found what they believed to be a Perry “hit list” naming other potential victims, including Justice Sandra Day O'Connor.35

Gavin de Becker, the security expert who had been tracking Perry since his stalking of Olivia Newton-John, told us that he believed Perry went to Washington, DC, to kill Justice O'Connor. “Michael Perry had said that he believed that no woman should be in a place that high and that he pursued her for that reason,” according to de Becker.36 There is also an ethical component to this mystery. If a justice is aware that his or her life may have been endangered by a convicted murderer, should he or she be deciding whether that murderer goes to the electric chair? Justice O'Connor participated fully in the Court's consideration of Michael Perry's case. When the authors inquired about the possible conflict at the time of the Court's ruling in 1990, the justice issued a statement saying she was “unaware” of any threat posed by Mr. Perry.

That's understandable, given the fact that threats against the Supreme Court justices are received with such frequency so as to be unremarkable. But she did thank de Becker for the warning, at the time, in a letter he shared with us. “Unfortunately there are people in our country who are sufficiently unstable to constitute genuine threats to the safety of others,” Justice O'Connor wrote. “I am very grateful for the information you shared concerning Michael Perry. You have helped to prevent what could have been a serious problem.”37

By order of the United States Supreme Court, the decision on the fate of Michael Perry would move far away from Foggy Bottom and the hazy memories of Washington, DC, back to a boxlike building just off Interstate 12 in Baton Rouge—the courtroom of Judge L. J. Hymel.

Hymel, a lifelong Baton Rouge resident with a background as a prosecutor at both the state and the city levels, had been elected to a state district court bench in 1983. He would later be appointed a U.S. attorney by President Bill Clinton. It was Hymel's court order to medicate and execute Michael Perry that the U.S. Supreme Court had “vacated and remanded” five months before Hymel again gaveled his court to order on April 25, 1991.

The session was short. There were no arguments; each side had submitted briefs and the judge was prepared to rule. “I have essentially done what the U.S. Supreme Court ordered me to do,” Hymel announced. “It's my opinion that Washington v. Harper doesn't change any of the conclusions I reached on Oct. 22, 1988.” He then reissued his original order that Michael Perry be forcibly medicated to allow his execution. “There is no question that Louisiana's interest in carrying out the verdict overrides Mr. Perry's rights,” Hymel said.38 Hymel decried what he viewed as a lack of guidance in the Supreme Court's order. “I call upon the U.S. Supreme Court to answer this question forthrightly,” Hymel said. “We're not dealing with some penological requirement. This is a case dealing with mental competence to proceed.”39

“I was frustrated,” Hymel told the authors almost twenty years later. Looking back, he felt the Supreme Court had failed to deal with the central issue of medication after a verdict: “The jury determined the defendant's guilt and decided on the death penalty,” Hymel said, “and I thought the verdict should be given effect. A defendant should not be able to escape the verdict of a jury by refusing medication.”40

Hymel was not alone in his frustration. In the interim between the Supreme Court finding and Hymel's hearing, Assistant Attorney General Salomon had filed another appeal to the high Court imploring the justices to decide the underlying issue of medication to enable execution; his petition was denied without explanation.41 The justices remained mute.

Keith Nordyke then unleashed a new assault upon the Louisiana Supreme Court, hoping that the remand from Washington might carry more weight with the state's highest court than it did with Hymel. He was right; the state supreme court essentially reversed itself on the same set of facts—and the identical Hymel order—after reexamining the case in light of Harper. The court's decision read:

The trial court's determination that Perry is not competent for execution without the influence of antipsychotic drugs is affirmed. The court's order requiring the state to medicate Perry with antipsychotic drugs without his consent is reversed. The execution of the death sentence is stayed.42

The Louisiana high court interpreted the remand order very differently from Judge Hymel. “As the Supreme Court has recognized,” the 5–2 state supreme court decision read, “the forcible injection of antipsychotic drugs into a nonconsenting person's body, even when done in his medical interest with medical appropriateness, represents a particularly severe interference with that person's liberty.”

The scholarly decision, written by Justice James Dennis, analyzed the way the U.S. Supreme Court had dealt with the concept of “cruel and unusual punishment” through a variety of cases—from the abortive electrocution of Willie Francis through the more contemporary legal travails of Troy Gregg, William Henry Furman, Alvin Ford, David Riggins, and Walter Harper. It dissected Louisiana law on the issues of punishment and personal freedoms. In thirty-nine painstaking pages, the court artfully reversed its conclusions of 1986.43

Michael Perry's life was spared; he did not have to take the state's medicine. “Carrying out this punitive scheme would add severity and indignity to the prisoner's punishment beyond that required for the mere extinguishment of life,” Justice Dennis wrote.

And the court stuck by its guns: less than two months after the ruling, the state attorney general's office filed another appeal, labeling as “ridiculous” the court's conclusion that the state's interest in carrying out the death penalty was not sufficient to override Perry's interest in refusing medication. The court ruled, again by a vote of 5–2, that it was dead serious about its conclusion.

Michael Perry, who is not eligible for parole, is serving his life sentence as Inmate number 111850 at Angola State Prison, a forbidding eighteen-thousand-acre penitentiary that is the largest in the United States. He will presumably die there, and, if his body is unclaimed by relatives, he will be buried in Angola's Point Lookout Cemetery.

The case of Perry v. Louisiana is closed. But the question of medicating to execute is still open, waiting to be addressed again by the United States Supreme Court.

|

For a video report on the Perry Supreme Court case, go to: http://murderatthesupremecourt.com/perry |