Execution is an excessive and disproportionate punishment, in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments, for one who did not himself take life, attempt or assist in taking life, and for one who did not intend that life be taken by another.

—Attorney James S. Liebman, arguing in Enmund v. Florida, 458 U.S. 782 (1982)

If Tom Kersey had it, he flaunted it. “He had a bad habit of flashing his money,” said Perry Knight, “the kind of thing that can lead to trouble.” Knight, who would later become the mayor of Bowling Green, Florida, was reflecting on the 1975 murders of Kersey and his wife, Eunice, just outside of town.1 Kersey's family viewed his bankroll habit as a harmless eccentricity—but it would prove fatal.

The Kerseys—he was eighty-six and she was seventy-four—cultivated vegetables and raised pigs and cattle on their small farm in the rural, central Florida community. Tom Kersey would preach at a small country church on Sundays and tend to his farming chores during the week. The farm had been home to their four children, who were now grown and on their own. The story of the bloodbath on that farm begins with a routine event in the Kersey's life: the sale of a cow.

In negotiating the sale with Earl “Dewey” Enmund, Kersey maintained that he didn't need Enmund's money, that he wasn't anxious enough to accept less than he was asking. “See, I ain't broke,” he said, pulling a fat wad of bills out of his pocket. The argument worked; Edmund paid cash for the cow.2 “Daddy didn't believe in banks,” Mary Lee Albritton, Kersey's only surviving daughter, told us.3 “He loved to flash his money,” repeated Perry Knight, who recalled being in a little country store when Kersey pulled out a huge roll of bills and made a production out of slowly counting off five one-dollar bills. “He liked to play with it,” said Knight.4

The image of Kersey's bankroll stayed with Enmund, age forty-two. He told the story to his twenty-three-year-old son-in-law, Sampson Armstrong, and Armstrong's nineteen-year-old wife, Jeanette. The three of them concocted a scheme to, as Mary Lee Albritton put it, “Get back his money, and then some.”5

Around 7:30 on the morning of Tuesday, April 1, 1975, Sampson and Jeanette Armstrong knocked on the Kerseys’ front door; Sampson had a .22 caliber pistol in his pocket. Earl Enmund waited on the road in a yellow Buick—“He would have been recognized,” Jeanette explained later. Enmund was accompanied by his common-law wife, Jean Shaw, who was Jeanette Armstrong's mother.

The Armstrongs asked for water for an “overheated car” and were directed to the rear of the house, where Tom Kersey met them with a jug. Jeanette's confession, recorded on tape, tells what happened next:

Sampson pulled the gun. The old man said, “Don't kill me. I'll give you the money, but don't shoot.” Sampson grabbed him around the neck at the back door and put the gun in his back. The old man was struggling and yelling to the woman. He told her to get the gun.6

Eunice Kersey came out of the house shooting. She wounded Jeanette Armstrong with her .38 caliber revolver, but by then Sampson was firing back. Thomas and Eunice Kersey were fatally wounded. The Armstrongs dragged them inside to the kitchen. An autopsy would determine that Thomas had been shot twice; Eunice, six times.

“They bled to death,” said Mary Lee Albritton. The bodies were found a short time later by her older sister, Margaret King. “There was a huge pool of blood,” recalled longtime Hardee County sheriff Newt “Duke” Murdock, “and that gave us our first clue.” A blood sample was found that did not match the Kerseys; it was evidence that Eunice Kersey had wounded one of her killers.7

Within a day, investigators got a report of a gunshot victim being treated at Walker Memorial Hospital, about twenty-five miles east of Bowling Green. The victim, Jeanette Armstrong, claimed she had been hit by a stray bullet in a field near the county line. The .38 caliber bullet, which had entered her left breast, was lodged against her spine; doctors could not remove it. “We couldn't make a ballistic comparison” with Mrs. Kersey's gun, Murdock said, “so we couldn't arrest her.”

If Tom Kersey's vanity contributed to his death and that of his wife, there is rough justice in the fact that Sampson Armstrong's bragging led to his own arrest and that of his coconspirators.

It started with a rumor. A deputy sheriff in neighboring Highland County heard that someone was claiming knowledge about the Kersey crime. When he tracked the story to its source, a man named J. B. Neil, he hit a dead end. Questioned by the deputy and then by Duke Murdock, Neil claimed he knew nothing. Murdock was determined to break through Neil's stonewalling. He decided to try another tack. “We brought him back in and sat him down,” Murdock said. “I pulled out ten one-hundred-dollar bills and told him he'd get five when he gave me the names and five when he testified. He started singing.”

Neil said that Armstrong and Enmund had boasted to him about the Kersey robbery-homicide, and Neil provided details to Murdock that had not been released. The information was solid enough to justify arrest warrants for Sampson and Jeanette Armstrong and Earl Enmund. “We got them,” said Murdock.8

The trial of Sampson Armstrong and Earl Enmund lasted five days; the jury took only four hours to convict them of first-degree murder. A sentencing hearing and the jury's decision to impose the death penalty all took place in an additional hour. Judge William Norris immediately pronounced the death sentences.

Jeanette Armstrong was convicted of second-degree murder in a separate trial and sentenced to life in prison. She served twenty-seven years of that sentence before being released in 2007 at the age of fifty-one. None of the interviews done by the authors long after the crimes, nor any of the surviving records, indicate that race played a part in either the crimes or the punishments. The victims were white; the perpetrators, black. But by all accounts, there were no troubling racial tensions in Hardee County.

The death sentences of “Dewey” Enmund and Sampson Armstrong were handed down in the four-year interval between the Supreme Court's Furman and Gregg decisions. The death penalty may have been on a legal holiday, but “Old Sparky,” the oak electric chair built by prisoners in 1923, was being regularly tested and maintained in a state of readiness at the Florida State Prison in Starke. The death penalty was reinstated in 1976 by Gregg while the two men pursued their appeals; their lives were again in jeopardy.

It was Enmund's case that eventually reached the U.S. Supreme Court. “Earl Enmund did not himself take life,” attorney James Liebman told the justices in oral argument on the morning of March 23, 1982. He contended that “execution is an excessive and disproportionate punishment,” violating the Eighth Amendment, for someone who did not kill or intend to kill. In essence, Liebman was making a distinction that Florida law did not, between a gunman and a getaway driver.

The Court agreed, sparing Enmund's life by a one-vote margin. Justice Byron White wrote for the majority, saying the “cruel and unusual” punishments clause of the Eighth Amendment guards against punishments that, because of their severity, are “greatly disproportioned to the offenses charged.” He noted that Enmund was not present at the killings and that there was no proof of a homicidal intent or anticipation of lethal force on his part.9

In his writing for the majority, White also referred to the 1977 Coker decision (discussed in the previous chapter). It was in that case that the Court first addressed the issue of proportionality in the application of the death penalty, ruling that a rape not involving murder was not a capital crime.

Earl Enmund, prisoner number 049515, is, at this writing, under what the state corrections department terms “close custody” at its prison in Dade County, genteelly called the South Florida Reception Center.

Enmund's son-in-law, Sampson Armstrong, had his sentence reduced on appeal to life in prison. His attorneys successfully argued that the judge's instructions to the jury during the sentencing phase of the trial were faulty; the instructions incorrectly limited the jury's consideration of mitigating circumstances. Armstrong is serving his sentence more than a hundred miles north of Enmund, in a penitentiary at Lake Okeechobee.

The Enmund case was the first in which the Court determined that the degree of participation in a murder affected the application of the death penalty. Five years later, in 1987, the justices chose to delve even further into the difficult territory of proportionality when they accepted an appeal from Arizona.

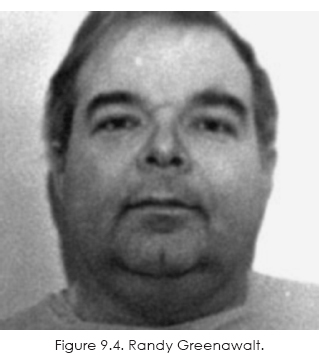

From a satellite view, the pavement of Route 95 near Quartzsite, Arizona, looks like it has been photoshopped onto the surface of the moon, a black ribbon cleaving through desolation. In the early-morning hours of August 1, 1978, the silence of the empty desert along the highway was shattered by sixteen blasts from a 20-gauge shotgun. Eleven of them were fired by Gary Tison, a convicted murderer and escaped prisoner; the others were fired by Randy Greenawalt, another murderer who had escaped with Tison from the Arizona State Prison.

The shotgun pellets ended the lives of John and Donna Lyons; their twenty-three-month-old son, Christopher; and a fifteen-year-old niece, Theresa Tyson (whom everyone called Terri Jo). It was point-blank, deliberate murder: the victims were herded into an abandoned car and slaughtered in their seats.10

A short distance away, near a car that had been hijacked from the Lyons, the shots were heard by Gary Tison's three sons, ages eighteen, nineteen, and twenty. The three had helped their father and Greenawalt escape from prison. Although they did not pull any triggers that August night, their role would become central in a legal battle that would be decided by the nation's highest court. It was a case in which filial love led to felony murder, and then to death row.

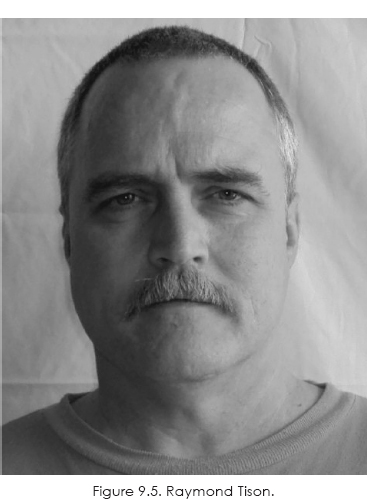

Gary Tison, who first saw the inside of a jail at sixteen, had been serving two consecutive life sentences for the murder of a prison guard. In a walled community riddled with racial and gang tensions, he was known as a tough customer. “Nobody messed with him,” said Lieutenant George Goswick of the guard detail, “he was not someone you would want to cross.”11

“I've never seen a man yet that was too big to tangle with,” Gary Tison told a court-appointed psychiatrist in 1961. Dr. William McGrath took him at his word: “Mr. Tison,” he wrote, “is impressed with being dangerous.” He diagnosed Tison as a sociopathic personality capable of “pronounced moral perversity [and] criminality.”12

He had a burly, broad-shouldered body and a menacing manner—one convincingly captured by stone-faced actor Robert Mitchum, who played Tison in a 1983 movie. Despite his fearsome reputation, Tison was considered a model prisoner. He was housed in a moderate-security wing of the state penitentiary in Florence, Arizona. The facilities included a grassy area inside the gates, where families were allowed to picnic with prisoners.

On the morning of July 30, 1978, a Sunday, the three Tison boys presented themselves at the visitors’ entrance, guns hidden in a cardboard box under a checkered tablecloth. They took over the guard station, aided by Greenawalt, who worked behind the counter as a clerk. He, too, was serving a life term for murder. Tison and Greenawalt changed out of their prison uniforms into western wear brought by the boys, and then the five of them casually strolled out of the prison gates to their car. They pulled away uneventfully, heading out of the prison grounds under the shadow of a silent guard tower.

Tison's sons felt they had been driven by desperation into arranging the escape. Their father had been behind bars most of their lives and was slated to die there. In fact, Gary Tison bitterly joked, with consecutive life sentences, he'd still have time to serve after his death.13 Donald Tison, the eldest boy, had served two years in the Marine Corps and was taking criminology courses at the local community college; his two brothers had been visiting their father in prison since they were eight and nine years old.

The getaway car, a green Ford Galaxie, pulled into a hospital parking lot where the boys had prepositioned a white 1969 Lincoln Continental. They made the switch and pulled out onto the highway again, undetected and unpursued. That second car would break down near Quartzsite the following night and become an execution chamber for the Lyons family.

John Lyons was a twenty-four-year-old Marine about to finish a two-year assignment to the Marine Air Station in Yuma. He and his family were headed home to Omaha, Nebraska, for a visit with relatives; son Christopher's grandparents were going to meet him for the first time. Lyons spotted a young man waving for help on a dark stretch of Route 95 and pulled to a stop near Ray Tison, the youngest son, and his immobile Continental. While Ray engaged Lyons in conversation, his partners emerged from the darkness with guns in their hands. John Lyons had a loaded Colt .38 in the glove compartment, but he had no opportunity to reach it.

The Tison crew was after the Lyons’ new Mazda. They maneuvered the Lincoln off the road into the desert and shepherded their prisoners in its wake. Gary Tison ordered them into the car's back seat and sent his sons back to the Mazda.

Donna cradled Christopher; Terri Jo Tyson held the family's trembling pet Chihuahua in her arms. John Lyons pleaded for their lives. Before the boys left, they heard him say, “Please don't hurt my family. Just leave us out here and you all go home. Jesus, don't kill me.”14

When the shooting started, Donna tried to shield the baby with her body. There was no protection possible; the shotgun pellets riddled the bodies of all of the victims. The interior of the car was carnage, strewn with fragments of flesh, bone, upholstery, and glass. Unlike her relatives, fifteen-year-old Terri Jo did not die immediately; her body was found a quarter of a mile away from the car. She apparently crawled that far despite mortal bullet wounds to the thigh and abdomen.15

A week later, the gang killed again in order to change cars. After crossing into Colorado, Gary Tison and Randy Greenawalt left the boys alone in the woods for a short time and returned driving a new van. The bodies of the van's owners, James and Margene Judge, riddled with gunshot wounds, were later found at their campsite near Pagosa Springs. The Judges, from Amarillo, Texas, had been on their honeymoon. James was twenty-six; Margene, twenty-five.

Gary Tison had hoped to hook up with a friend who owned a small plane that could fly his crew to Mexico. It didn't work out; in fact, the gang narrowly escaped capture. The “friend” tipped off police, who set up an undercover cordon around the airplane. The Tisons spotted the stakeout and hit the road again.

Their luck ran out on Interstate 10 as they returned to Arizona. Police had set up two roadblocks and were on the lookout for the stolen Mazda. They were taken by surprise when the Tisons rolled through the first roadblock in the Judges’ van, guns blazing, but they were more prepared at the second location. Deputies from the Pinal County sheriff's office peppered the van with gunfire; it rolled slowly to a stop a short distance away.

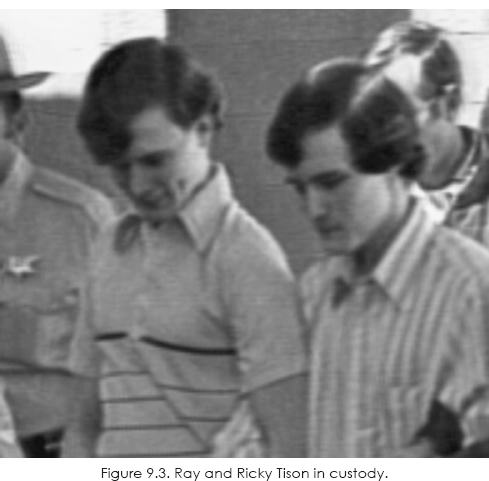

The body of twenty-year-old Donald Tison, the eldest brother, was found in the driver's seat. The others had fled—but in the foot chase and search that followed, Randy Greenawalt was captured, as were Ray and Ricky Tison, ages eighteen and nineteen, respectively. Gary Tison escaped the police manhunt, but not the Grim Reaper. He died in the desert of exposure; his body was found eleven days later.

Greenawalt and the surviving Tison brothers were convicted of the murders of the Lyons family and their niece, and the three were sentenced to death. No charges were ever brought in the murder of the Judges: Colorado authorities closed that case believing that an additional trial of the perpetrators, Gary Tison and Randy Greenawalt, was unnecessary.

Before the three defendants went on trial in Arizona for murder, attorneys for Ray and Ricky Tison had negotiated a plea deal that would have taken the death penalty off the table in exchange for their testimony. But in a meeting with Judge Douglas Keddie, the brothers balked when he informed them they would not only have to testify against Greenawalt but also about the prison break. Since that could have put their mother further at risk as a suspected participant in the planning, the two rejected the deal.

“I'm not involving anyone else,” Ray said. “I understand we already got our lives in prison. What's it going to hurt?” As author James W. Clarke noted in his classic book about the case: “It was the wrong question, asked in the wrong way, at the wrong time, of the wrong judge.”16

The three defendants were tried separately before Judge Keddie for the Lyons and Tyson murders and found guilty of first-degree murder. Sentencing for all three was on March 29, 1979, and Judge Keddie had decided their fates identically: death in the gas chamber. Ray's question was answered.

Under Arizona law, it didn't matter whether the Tison brothers had pulled a trigger or had participated in planning a murder. The fact that they were participants in the events leading up to the murders was enough, under state law, to establish criminal intent. This is the so-called principal-accessory rule, on the books in most states. Plainly put, an accessory before the fact is as guilty as the principal. They were also vulnerable to capital-murder charges under Arizona's felony-murder rule. That rule, also common in many jurisdictions, provides that one who participates in a felony is liable for all natural consequences of the felony, including murder. Ricky and Ray Tison were every bit as eligible for the gas chamber as Randy Greenawalt.

As the long pursuit of appeals played out, the Tisons’ lawyers saw hope in the Supreme Court's ruling in Enmund. The Court agreed to hear their case, and on November 3, 1986, attorney Alan Dershowitz stood at a lectern before the nine justices and declared, “There is no difference between this case and Enmund, except that this case is far more compelling.”17

The justices did not agree about the difference. They did, however, agree that the issues were more compelling—but not the way Dershowitz saw them. In a 5–4 decision, they held that the brothers’ actions could be viewed as far more culpable than Earl Enmund's. There was no doubt, as Justice Sandra Day O'Connor said in her majority opinion, that they were “major participants” in the series of crimes that began with the prison break and continued through the murders. The key question, she wrote, was whether they had acted with “reckless indifference to the value of human life.” If so, their own lives could be forfeit.18

This was a significant expansion of the Enmund criteria—and it came about under unusual circumstances. According to the Court historian Edward Lazarus, Justice O'Connor had entered the Conference Room fully prepared to vote to reverse the Tisons’ death penalties, based on Enmund. He reports that O'Connor was swayed when Justice White, who had written the Enmund decision, voted to uphold the death sentences.19

The good news for the Tison brothers—the temporarily lifesaving news—was that the Court decided to remand the case back to Arizona's trial court to determine whether this newly stated “reckless indifference” standard had been met. The trial court found that it had been met and reaffirmed the death sentences.

It was a legal rollercoaster ride for the Tison brothers, dizzying and nearly fatal, but the Arizona Supreme Court ended it just short of the gas chamber. The justices ruled that because the Tisons were under twenty at the time of the crimes, the death penalty could not be imposed under Arizona law.

Randy Greenawalt died where it all began, at the Arizona State Prison in Florence. He was executed on January 23, 1997, by lethal injection. James Clarke was a witness and, although he has reservations about capital punishment, he had no doubts on that day. “Randy Greenawalt,” he said, “grew older and died a lot easier than any of his victims.”20

Ray and Ricky Tison now live in the Florence prison. In all likelihood, they will die there.

|

For a video report on the Tison Supreme Court case, go to: http://murderatthesupremecourt.com/tison |