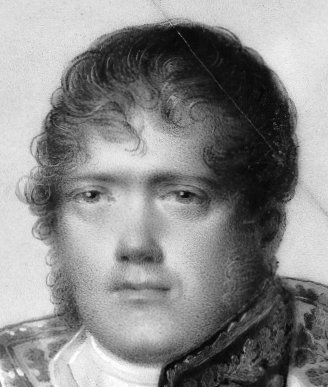

This sketch of Napoleon, made by Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson in March 1812, shortly before the Emperor’s departure for the Russian campaign, shows the unhealthy plumpness which had recently set in, belying his attempt to appear aquiline.

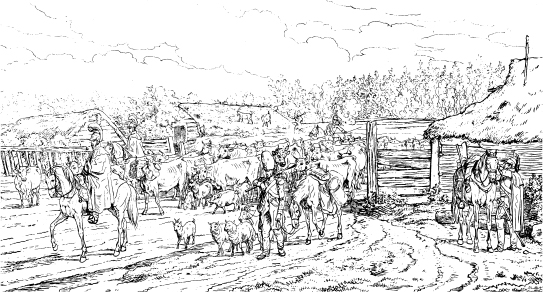

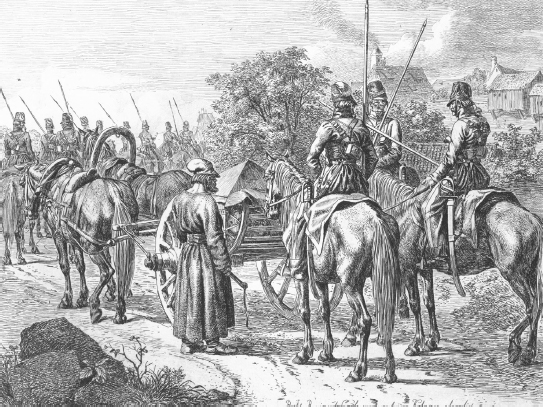

The French army on campaign was a far cry from the glorious image suggested by most military prints, as this scene, drawn from life by Albrecht Adam, shows. Here, a party of cuirassiers are concerned with the vital business of herding food on the hoof.

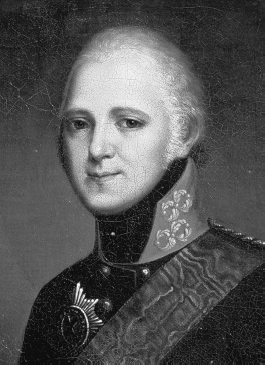

Tsar Alexander I, painted by Gerhard von Kügelgen in 1804, the year he denounced Napoleon as an upstart and before he had been forced to flee from him on the battlefield of Austerlitz.

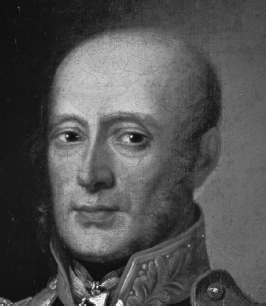

General Mikhail Barclay de Tolly, Russia’s Minister of War and commander of the First Army, a brave but prudent soldier who knew the limitations of his force, by an unknown artist.

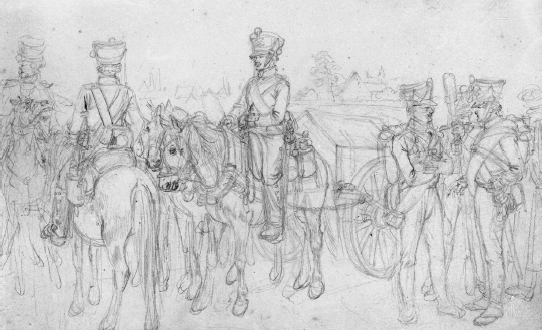

A group of Russian gunners, drawn from life by Johann Adam Klein.The Russian artillery was probably the best in the world at the time.

General Prince Piotr Ivanovich Bagration, commander of the Second Army, a firebrand who believed he should be in overall command, sketched at the start of the campaign by one of his staff officers, General Markov.

General Count Levin Gottlieb Bennigsen, who, despite having been soundly beaten by Napoleon at Friedland in 1807, believed he should be in command in 1812, by George Dawe.

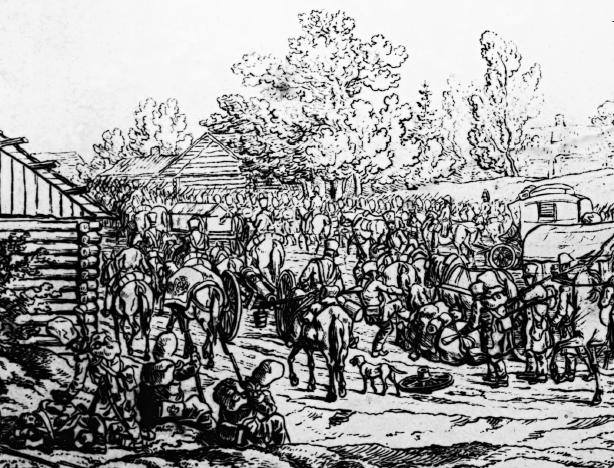

Cossacks on the march, by Johann Adam Klein.A type of light cavalry recruited largely from the cossacks of the Don and the Kuban, they were used mostly to harry rather than to fight.Those depicted here belong to one of the regular cossack regiments.

Napoleon’s stepson Prince Eugène de Beauharnais, Viceroy of Italy, loved throughout the army and esteemed by his peers for his bravery and chivalry, by Andrea Appiani.

Marshal Davout, a strict disciplinarian, probably the most capable and loyal of Napoleon’s marshals, from a miniature on porcelain by Jean-Baptiste Isabey.

RIGHT Joachim Murat, King Joachim I of Naples, a legend of dash and flash who invented his own uniforms. Detail from a painting by Louis Lejeune, a colonel on the general staff.

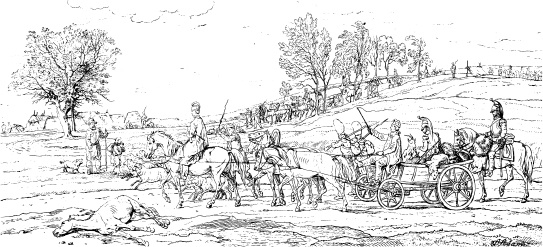

BELOW Elements of the Army of Italy on the march on 29 June, shortly after crossing the Niemen, sketched by Albrecht Adam, an artist attached to Prince Eugène’s staff. At the centre of the picture, an officer has drawn his sabre to try to get a cantinière’s wagon out of the way of his marching men.

A French infantryman returning from the maraude, on a small peasant pony typical of the type to be found in this part of the world, a drawing by Christian Wilhelm von Faber du Faur, a Swiss artist serving in the Württemberg contingent of the Grande Armée.

Portuguese infantry returning from a foraging expedition, by Faber du Faur.

A Bavarian cavalryman haggling with Jewish traders, by Faber du Faur.

French cuirassiers returning from a foraging expedition, by Albrecht Adam.

ABOVE This scene, sketched by Albrecht Adam near Pilony on 29 June, shows how inexperienced many of the men were at the tasks of butchering and cooking.

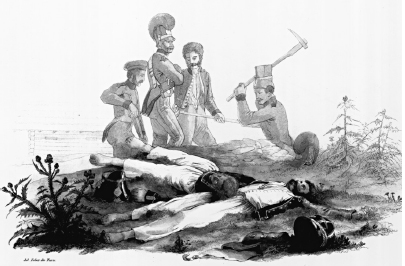

ABOVE A detail of Württembergers on grave-digging duty, by Faber du Faur.

RIGHT Tents were not part of the French army’s equipment, and the only shelter the men could hope for was one constructed with straw or foliage, like this one, depicted by Faber du Faur.

The fierce rainstorm that assailed the Grande Armée four days after it crossed the Niemen slowed progress. This engraving by Faber du Faur shows French artillery teams floundering through a sea of mud on 30 June.

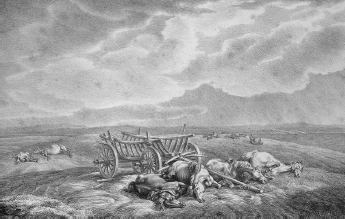

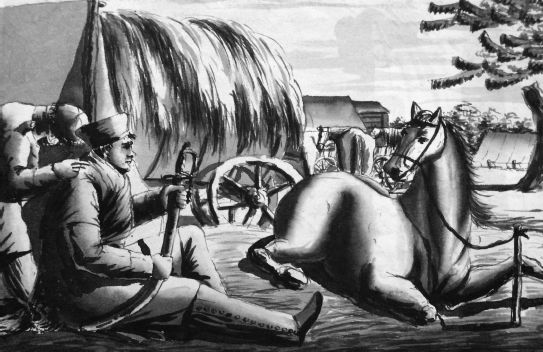

The conditions took a heavy toll of the French army’s horsepower, and it is thought that as many as 50,000 horses may have died in the space of twenty-four hours, often in harness, like these drawn by Albrecht Adam on 29 June.

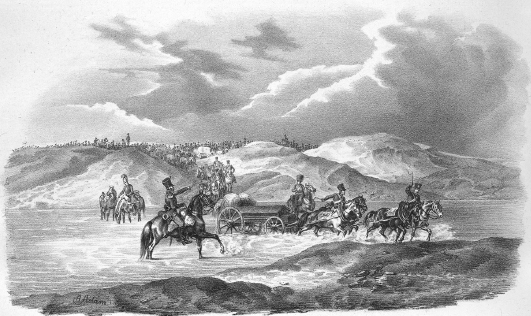

The territory through which the French were moving was criss-crossed by a multitude of rivers, most of which had to be forded. Here, Albrecht Adam shows Prince Eugène’s 4th Corps on 29 August crossing the river Vop, which was to prove a fatal obstacle on the way back.

In this print, made from drawings done on the spot by Faber du Faur, Russian light infantry can be seen fighting a rearguard action in the suburbs of Smolensk against German grenadiers of the Grande Armée.

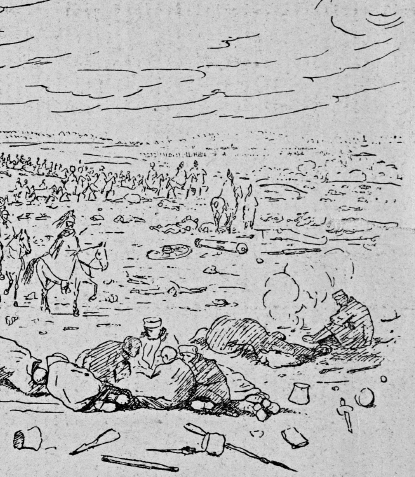

French artillery facing Borodino on the afternoon of 5 September, by Albrecht Adam.

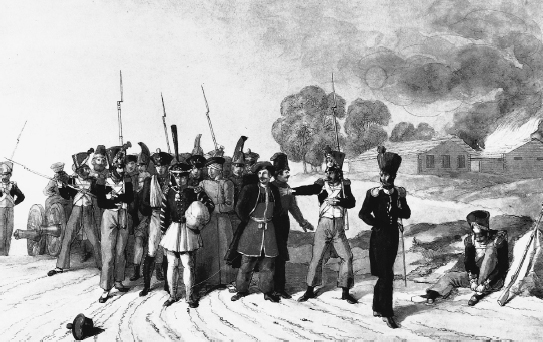

Russian prisoners being led away by French light infantry after the battle of Borodino, by Faber du Faur.

General, later Prince and Field Marshal, Mikhail Ilarionovich Kutuzov, named commander-in-chief of the Russian armies as their continuous retreat threatened disintegration. This etching by Hopwood clearly shows his sagging right eye, the result of a musketball passing through his head and severing the muscle behind it.

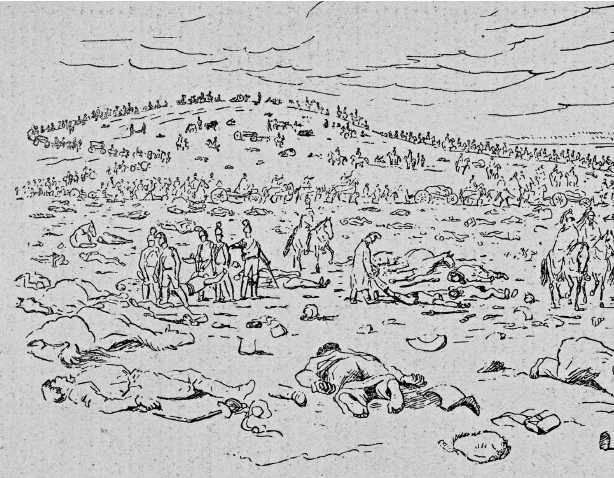

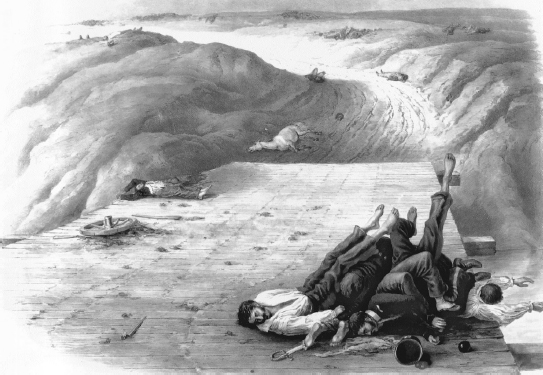

The field of Borodino, sketched on the morning after the battle by Albrecht Adam. Not until the first day of the Somme in 1916 were so many to be killed in a single day’s fighting.

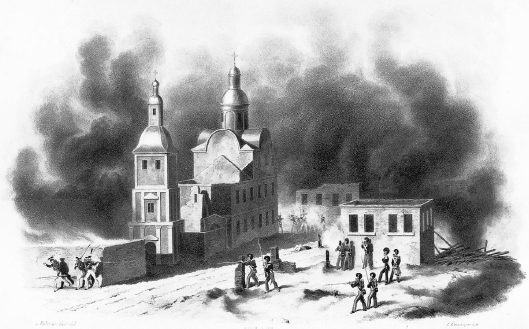

French soldiers looting as Moscow burns, by Albrecht Adam. The group at the centre provide a good illustration of the extraordinary range of objects taken from the houses and palaces of the gentry, most of which would be jettisoned along the road during the retreat.

Looters at work and surviving inhabitants among the ruins of Moscow, by Faber du Faur. Note the tin roof lying up-ended at the centre of the picture. These roofs were lifted in one piece and sent flying up into the air by the rush of hot air generated as the houses they covered went up in flames.

Count Fyodor Vassilievich Rostopchin, Governor and destroyer of Moscow, intelligent, cultivated, and possibly mad, by Orest Adamovich Kiprensky.

The troops passed their time as best they could in the ruins of the burnt-out city, waiting for Napoleon to decide on the next move, as this group, sketched by Faber du Faur on 8 October, shows. The weather was growing cold, which is why the sentry is wearing his greatcoat. Two of the card-players are wearing the bonnet de police, the forage cap worn off-duty.

A gloomy French sentry watches over the burnt-out suburbs of Moscow, a lithograph by Albrecht Adam after a sketch made on the spot which epitomises the hollowness of the French victory.

The roadside between Mozhaisk and Krimskoie, sketched on 18 September by Faber du Faur. Stragglers and wounded shelter in the corner of a stove, all that remains of a wooden dwelling, whose occupants’ corpses were calcinated when it was burnt down. By all accounts, this was the picture all along the road travelled by the Grande Armée, and is characteristic of conditions in its rear.

As the French cavalry’s horses perished, they were replaced by the little local ponies, with ludicrous results in the case of cuirassiers and carabiniers such as these, who were specially selected for their height and were supposed to be mounted on large horses. Pen, ink and wash by Faber du Faur.

Armand de Caulaincourt, drawn here by Jacques Louis David, was a wise and devoted friend to Napoleon, whom he had consistently discouraged from invading Russia, foreseeing the worst.

As this lithograph from a drawing by Faber du Faur shows, even the bridges over the Kolocha at Borodino in the Grande Armée’s rear had not been cleared of the dead and debris of battle.

Three irregular cossacks enjoying a meal, by Jean-Pierre Norblin de la Gourdaine.

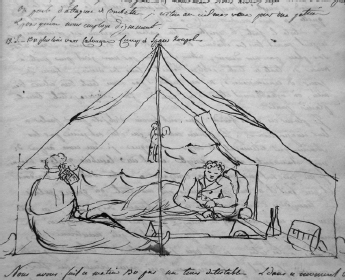

Lieutenant Aleksandr Chicherin of the Russian artillery made this sketch of himself writing his diary on 2 October while his comrade S.P. Trubetskoi looks on. Although they were in despair at the abandonment of Moscow, the Russians were beginning to realise that the French were in worse condition than themselves.

This forty-five-year-old retired officer who had returned to service in order to defend the fatherland was characteristic of a class of patriots, and was dubbed ‘Le nouveau Donquichotte’ by Chicherin, who drew this picture of him in his diary. He would spend whole days dreaming of vanquishing the French, but when his favourite horse, ‘Mavr’, was stolen, he went into a decline and fell behind.

When the temperature dropped on 6 November, Napoleon exchanged his characteristic Chasseur uniform, greatcoat and tricorn hat for a Polish-style fur-lined coat and hat. He was sketched by Faber du Faur as he warmed himself by the roadside at a fire made of the limbers and wheels of an abandoned gun near Pneva on 8 November. Behind him stand Berthier and, in plumed hat, Murat.

The French were now assailed by hordes of irregular cossacks, more feral and vicious than their brothers in regular regiments, who preyed mercilessly on the stragglers. This drawing, by Aleksander Orłowski, captures the character of these fearsome, if not fearless, horsemen.

When Faber du Faur caught up with his fellow Württembergers on the morning of 7 November, after the first heavy snowfall and frost, he was surprised to find them still apparently asleep in their makeshift shelters. As he tried to rouse them he discovered that they had frozen to death. (See p.391.)

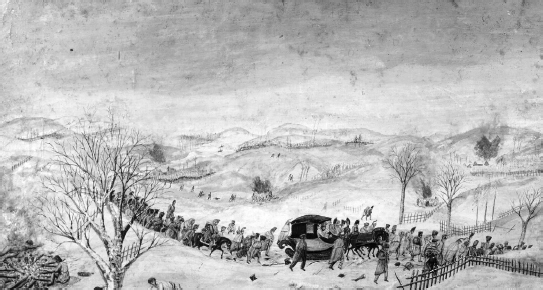

As can be seen from this watercolour by an unknown participant, the retreating column was in places little more than a procession of stragglers.

This lithograph by Faber du Faur depicts a group of men cooking up at Krasny on 16 November. The soldier on the left has donned a lady’s pelisse, originally booty destined for sale or for his beloved in Paris. The pair on the right have acquired a small pan, a life-saving implement which permitted men to make an improvised pancake out of whatever was available.

Marshal Ney, known as ‘the bravest of the brave’, whose exploits at Borodino and during the retreat earned him the title of Prince de la Moskowa, from a miniature on porcelain by Jean-Baptiste Isabey.

Artillerymen of the 25th Württemberg Division, part of Ney’s 3rd Corps, spiking the guns they no longer have the horses to draw and throwing them into the river Dnieper before moving out of Smolensk. The spike was driven into the firing-breach, making the guns unusable even if recovered. A lithograph by Faber du Faur.

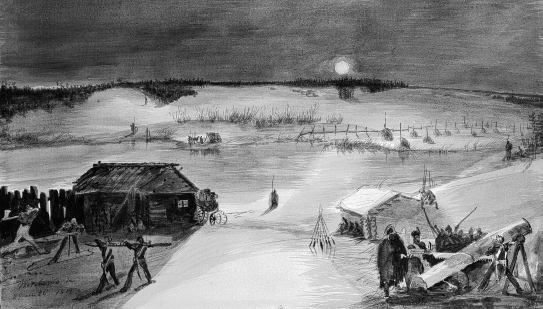

The river Berezina near Studzienka on the night of 25 November. The French pontoneers have just begun building the struts for the bridge. In the bottom right-hand corner their commander, General Eblé, can be seen directing the work. Across the river, a cossack picket is keeping an eye on the proceedings, and, beyond the woods in the top left-hand corner, the sky reflects the campfires of the Russian force which was supposed to prevent the French from crossing. The scene was drawn from life by François Pils, a grenadier in Oudinot’s corps. (See p.464.)

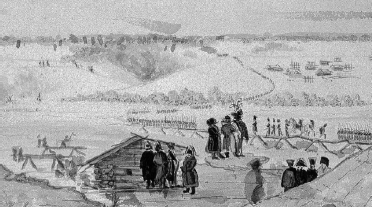

In the early hours of 26 November, Napoleon reached Studzienka. He is pictured here by Pils talking to Oudinot in front of the bridge-struts, which are ready to be hauled down to the river. The tallest struts, at about three metres, were nearly twice as tall as Napoleon.

LEFT This sketch by Pils shows Oudinot’s corps crossing the river on the first bridge, as Napoleon watches, flanked by Berthier and a plumed Murat.On the left of the picture, sappers are at work on struts for the second bridge.

RIGHT General Eblé sketched by Pils on 28 November as he exhorts stragglers to cross the river before he must burn the bridges.Note the soldier in the foreground cutting open a horse’s stomach with his sabre to get at its heart and liver, the most prized nourishment.

The Grande Armée bivouacking on the right bank of the Berezina on 27 November, by Faber du Faur.In the background, some generals who have taken over a hut are trying to prevent their shelter being dismantled from outside by men desperate for firewood, a frequent occurrence.

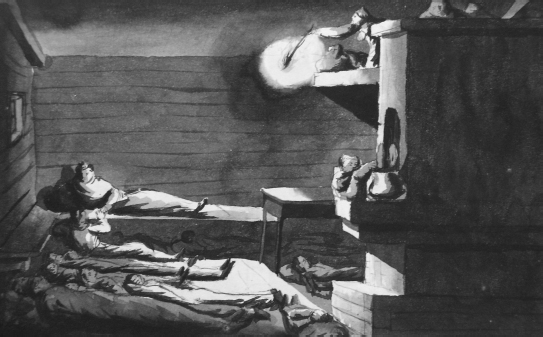

‘Billets – understand? Billets! Not a bivouac, not a camp, but real billets – a palace, paradise!’ noted Chicherin in his diary on 11 November, the first time they had not camped in the snow for two weeks.In his drawing of the scene one can see him and his brother officers pressed like sardines on the floor, with the luckiest ones on the shelf above the stove – the warmest place.

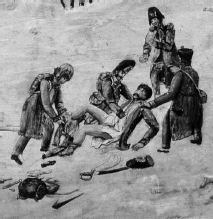

The pursuing Russians were under severe strain as well, both physical and psychological, and iron discipline had to be applied.This grim watercolour in Chicherin’s diary records the execution of a Russian officer.

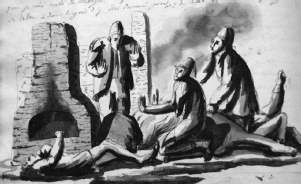

A dying man being stripped by his fellows, a watercolour by an unidentified participant.

This detail from a watercolour by an anonymous French soldier shows men cutting up a horse for meat.

‘The sight of these people so numbs the heart that in the end one ceases to feel anything at all,’ Chicherin noted over this drawing of a group of stragglers seeking a remnant of warmth among the corpses and embers of a burnt-out cottage.

Many witnesses noted that as they froze to death, men looked haggard and even appeared to be drunk. Detail of a lithograph by Faber du Faur.

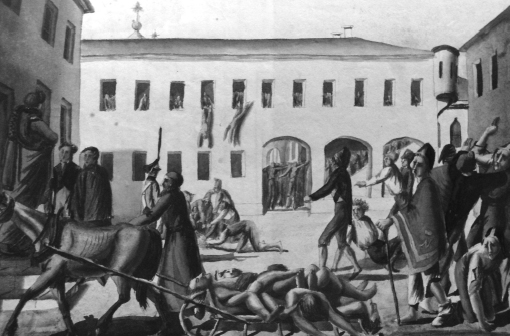

Remnants of the Grande Armée drifting into Vilna on 9 December, sketched by Jan Krzysztof Damel. Note the variety of bizarre raiments, including liturgical vestments, with which they have supplemented their uniforms.

Charles de Flahault, one of Napoleon’s aides-de-camp, carrying his servant David up the slope of Ponary outside Vilna, assisted by his secretary Boileau.Alerted to the fact that David had collapsed at the foot of the slope, Flahault had gone back to fetch him.By the time he arrived, the man’s boots had been stolen by a needy soldier.David could only wail: ‘Mon Dieu! Mon Dieu!’ as he was carried up, and died before they reached the top. A painting by Horace Vernet, executed under Flahault’s direction.

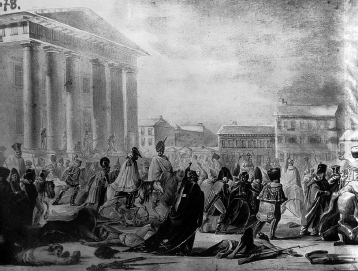

‘I cannot render the horror that overpowered me this morning,’ Chicherin wrote in his diary on 20 December, after visiting one of the improvised prisons in Vilna.Returning to his billet, he painted this watercolour, in which one can see corpses being thrown out of the ‘hospital’ windows, and others being carted away on a sledge, while emaciated French soldiers fight amongst themselves or wander aimlessly, wearing, in the case of one of them, little more than a horse-blanket.