Arousal Assessments for Parents, Teachers, & Therapists

These assessments are not standardized tools, but they do provide a gateway to begin the exploration of the child’s needs and desires. There are tools for therapists, parents, and teachers. The first section of the chapter provides an overview on arousal and threshold. Next, we explore possible underlying neurological components of the challenges our children face. This involves an in-depth look at primitive reflexes. Such information is geared toward professional licensed therapists or others working in collaboration with such professionals.

Last are hands-on activities for children and adults to use to perform self-assessments of self-regulation and learn new skills. Be sure to review the glossary in the back of the book to clarify specific terms. After gathering information from the assessments, use the daily targets to present the child with daily activities to help facilitate their self-regulation. Once you have knowledge regarding their arousal level, you can select activities that fit their needs while enhancing growth.

Before we get started on assessments, let’s talk about our measurement tool. We will use a self-regulation and mindfulness “radio” called a SAM box. It allows us to identify our arousal level at a given point in time. Arousal relates to our breathing, how fast our heart is beating, activity level, and attention. To function and engage appropriately, we desire to be in the middle range. Once we experience high or low arousal, we need to do something to get balanced again. This is not a unique concept: The Alert Program® provides a great foundation for self-assessment of arousal levels.

Our SAM box simply provides an alternate tool for assessing arousal, emotions, and sensory integration. It uses terminology similar to that on the volume controls of a radio. I describe ways in which the SAM box is multifaceted, but you can use the SAM box to approach the child’s arousal level. Following is an example of one way to use the SAM box for this purpose.

First, have the child describe their feelings in that moment. Ask the child to describe their breathing and heart rate. You can have them place their hand on their chest to provide additional feedback from their body. Provide examples of high arousal, such as heavy breathing and a fast heartbeat. Share how certain emotions can lead to heightened arousal. Then share that we call high arousal being “loud” on the SAM box. It is similar to a radio’s volume being turned all the way up.

Next, do the same for low arousal. Talk about how low arousal may feel by having the child perform activities such as taking a deep breath and closing their eyes. Then share that the SAM box defines this as being “quiet.” It is similar to having the radio’s volume turned down. If the radio is set too low, you will not be able to hear it. If the radio is too loud, you will not be able to focus on anything else, as the sound is too distracting. For most of our activities, we need our volume to be somewhere in the middle.

Use the SAM box to look at the child’s typical “volume” during play, school, or at home. You can then follow up by sharing how they can change their volume through what they do with their body! See chapter 6 to learn how to make your SAM box.

THRESHOLD AND AROUSAL OVERVIEW

It is important to note that some children have a form of SPD. They may also have another diagnosis, such as ASD or ADHD; however, the SPD diagnosis can stand alone. Children display various responses and behaviors depending on the environment, time of day, activity demands, and levels of rest and digestion. For all of us, there is a daily continuum of varying responses and arousal levels. Our diet, amount of rest, and activity levels result in our avoiding or engaging in certain behaviors, seeking or avoiding stimulation, and having periods of high arousal and low arousal.

Despite this continuum, there is often an overarching commonality. The following table provides an overview of some of the common themes children may embody. The threshold indicates how easily the child detects stimuli, or changes in their environment (low = quick detection; high = slow detection). A child’s arousal is the behavioral reaction to stimuli that we can observe. Please note, there are other areas of sensory dysfunction not covered in this table, which primarily focuses on modulation.

Threshold and Arousal Levels and Treatment Intervention

| OVER RESPONSIVENESS TO SENSORY INPUT | UNDER RESPONSIVENESS TO SENSORY INPUT | CRAVING SENSORY INPUT | |

| Threshold | Low; hypervigilant | High; inattentive | High; hyperactivity |

| Arousal | High; overreaction | Low; lacking a response | High; energetic |

| Preferences | Avoiding certain activities and preferring routine and predictable activities | Needing motivation and encouragement to attend to activities, especially gross motor play | High-intensity activities; risk-taking |

| Sample Treatment Activities | Slowly introducing new activities by pairing with nonthreatening preferred activities; weight-bearing activities; deep breathing; yoga; exercises moving from a flexed position to extension (to help reduce primitive reflexes) | Contrasting activities; fast versus slow; cold versus hot; high-energy activities, such as fast swinging, jumping, and crashing; strengthening activities if child displays decreased muscle activation due to lack of gross motor activities | Intense sensory activities, such as ice play; stimulating multiple sensory areas; swinging and crashing while listening to music; weight-bearing activities and intense input to the muscles and joints; deep breathing; yoga; meditation |

From Miller & Schaaf, 2008.

PRIMITIVE REFLEXES

Primitive reflexes occur at the brainstem level. Such reflexes are observable during the beginning stages of life. They are involuntary reflexes to help a newborn through the birthing canal, assist with feeding, and allow one to learn how to move their body. Yet, they eventually integrate allowing for a coordinated sensorimotor system. Some individuals still present with observable primitive reflexes (Konicarova & Bob, 2013; Taylor, Houghton, Chapman, 2005).

Activation of the lower brainstem area may result in lack of activation of the front part of the brain and the other structures for movement, sensory processing, and learning. When primitive reflexes are evident, one may present with poor coordination, emotional regulation challenges, and difficulty attending to and performing tasks. For example, a baby reveals the primitive reflex called Asymmetrical Tonic Neck, or ATNR, when the head is turned. One side extends and the other one flexes. This can occur both in the upper and lower limbs of the body. If the reflex remains retained, children may have various challenges with school-based activities, balance and coordination, and visual activities. A school-aged child may display poor sitting positioning during tabletop activities.

The following chart identifies the various primitive reflexes, their function, and examples of dysfunction. After the chart, talk about how to test children for primitive reflexes. Most should not be evident after the first year of life. Activation and evidence of such reflexes should be addressed with appropriate therapeutic intervention. Professional consultation, with an occupational or physical therapist, may be indicated.

| PRIMITIVE REFLEXES IN CHILDREN | ||

| PRIMITIVE REFLEX | FUNCTION | DYSFUNCTION |

| Asymmetrical Tonic Neck (ATNR) Appears 18 weeks in utero, disappears around 6 months |

Extension of one side of the body and flexion of the other to assist in the birthing process and later with reaching, eye-hand coordination, airway passage clearance | Poor balance; difficulty with coordinated eye movements needed for reading and writing; challenges in crossing midline of the body and separating the upper body and lower body movements |

| Symmetrical Tonic Neck (STNR) Appears 4–6 months, disappears around 8–12 months |

Assists in preparation for crawling; when the child is on hands and knees, a flexed head results in legs extending; when the head is extended, the opposite occurs, with arms extending and legs flexing | Difficulty crawling on all fours; poor balance; clumsiness; difficulty with midline activities; poor sitting position—“W” sitting |

| Moro Appears in utero, disappears around 6 months |

Occurs during the first breath of life; continues as a startle reflex in response to an unexpected stimulus or threat; the involuntary response is protective, as the infant is unable to distinguish threats; extension of the body (fall reaction), followed by full flexion (protective position), occurs spontaneously | Hypervigilant; overactive fightor- flight reactions; sensitivity to light, sound, touch; poor emotional regulation; hyperactivity; poor attention to task; frequent illness due to a stressed immune system; fatigue |

| Spinal Galant Appears 20 weeks in utero, disappears around 9 months |

Activates when either side of the spine of an infant is stroked; neck extension, hip rotation, and body flexion occur; assists with hip movement and rotation, specifically in utero and during the birthing process, as well as in the development of crawling. | Difficulty maintaining a seated position; constant fidgeting; bedwetting and bladder accidents; sensitivity to touch and certain textures (clothing); challenges in following directions and with shortterm memory |

| Palmar Appears 18 weeks in utero, disappears around 6 months |

Assists in sucking, as the hands contract as the baby sucks; stimulation of the palms results in flexion or a grasp reflex; activation also leads to the mouth opening and jaw movement | Mouth movement as the child performs cutting, writing, or coloring activities; chewing on objects such as pencils; biting people; difficulty with grasp and speech due to tension in hands and mouth |

| PRIMITIVE REFLEXES IN CHILDREN | ||

| PRIMITIVE REFLEX | FUNCTION | DYSFUNCTION |

| Rooting Appears at birth, disappears around 4–6 months |

Assists with feeding; baby will respond to stimulation of the cheek by turning toward the stroked side and opening mouth | Sensitivity in the mouth; challenges with food textures; messy eating; poor speech articulation |

| Tonic Labyrinthine Appears in utero, disappears around 4–6 months |

Assists baby through the birthing canal; as head is flexed, the arms and legs extend | Difficulty coordinating body movement and eye movement; motion sickness; poor balance and posture; poor timing and sequencing (dyspraxia) |

| Landau Appears 3 months, disappears around 12 months |

Head, legs, and spine extend when baby is held in the air horizontally; assists with muscle tone | Challenges with motor activities; high muscle tone (hypertonia) and difficulty learning; toe walking and lack of coordination; possible difficulty sitting against chair back; absence of the reflex during infant years indicates hypotonia and possible intellectual disability |

| Adapted from Retained Neonatal Reflexes (2005). | ||

| ASSESSMENT FOR LICENSED PROFESSIONALS OR THOSE IN COLLABORATION | |

| ATNR | • Have the child get on all fours • Gently turn their head or have them turn it to the side and hold for 5 seconds repeat on the opposite side • Look to see if they can maintain the position or if they fall to the side opposite of the head being turned

|

| STNR | • Have the child get on all fours • Gently move or have the child move their head up and down and hold for 5 seconds in each position • Look to see if they can maintain the position, if they have excessive movement in their trunk, or if they are sitting back on their legs

|

| Moro | • Have the child stand with both feet on the ground and tilt their head back to look at the ceiling • You can also ask the child stand on one foot with their arms out to the side • Look for loss of balance and excessive movement

|

| Spinal Galant | • Have the child get on all fours • Gently stroke the left and right sides of their spine • Look to see if they can maintain the position, if they have excessive movement in their trunk, or sitting back on their legs

|

| Palmar | • Have the child stand with straight arms and ask them to wiggle their fingers • You can also have the child face their palms toward the ceiling; stroke the hand from the thumb toward the palm • Look for excessive wrist movement and movement in the mouth and/ or tongue

|

| Rooting | • Gently stroke the cheeks and the above the upper lip of the child approximately 3-5 times • Look for head movement towards the direction of the stroke and mouth opening and movement |

| Tonic Labyrinthine | • Ask the child to get on their belly, extending their neck, lifting chest slightly off of the floor, with arms extended behind and legs straighten and elevated • Look to see if the feet turn upward with flexed knees

|

| Landau | • Ask the child to get on their belly, extending their neck, lifting chest slightly off of the floor, with arms extended toward the front of the body and legs straighten and maintained on the floor • Remind the child to lift up their chest but keep their feet on the floor • Look to see if the legs leave the floor as in the image above

|

BIOMARKERS

Biomarkers are physiological changes in the body related to heart rate, responses from our nervous system, and breathing. Biomarkers can be monitored to help identify a child’s typical arousal level and threshold response to stimuli.

Biomarker Assessments

The following biomarker assessments can be used for most children. It is recommended that you use these techniques in conjunction with a healthcare professional, such as an occupational, physical, or speech therapist. Basic application of these assessments may provide you with more insight regarding the child’s arousal and threshold. The following are important considerations before beginning an assessment of biomarkers:

• Acknowledge the child’s tolerance for touch, sitting, and participating in tabletop activities.

• The child needs to be able to sit still or lie down for at least 15 to 30 seconds. The child must also tolerate minimal touch for short intervals of time.

• Identify effective methods of communication: speech, pictures, gestures. The child needs to be able to follow directions, such as “look at me” or “let’s sit for a minute.”

• Obtain a penlight, stopwatch, and possibly a device to monitor heart rate (such as a sports watch that measures heart rate/pulse, which can be purchased inexpensively). The penlight will assist you in viewing the child’s eyes. The stopwatch or heart rate monitor allows you to monitor the child’s physiological response before and after selected activities.

Part I: Eye Test Changes in the eye’s pupil occur secondary to light stimulation. Research shows that pupillary dilation (widening of the pupil) occurs during periods of excitation, such as in fight or flight (Moshe et al., 2014). Some children with high arousal levels have dilated pupils on a regular basis. Changes in size, such as when a light is shined at the child’s eyes, would be minimal. In addition, irregular eye motor responses may be limited. Minimal eye reactions provide valuable information about the child’s nervous system responses; for example, a minimal reaction to light may indicate that the child’s fight-or-flight reactions are in constant overdrive or that there is a lack of flexibility or synchrony between the systems controlling regulation. Note that if typical responses are not seen, there may be a need to seek further medical evaluation. The eye assessment may also provide information regarding a child’s progress in treatment: When improved eye reactions, such as an increased pupillary response to light and a smaller resting pupil size, are seen, this may indicate that interventional activities are working.

There is not a specific measure to look for when conducting the following assessments: Each individual child is unique. What you see in their reactions will inform you, and the child, about their arousal and threshold.

Position and Environment Have the child sit in a chair. The room should be dim. Face the child and have them look straight ahead. If needed, place an item of interest on the wall or have a video playing in the distance behind you.

What to look for:

1. Size: Pupil size should be similar in both eyes. Normal size is about 3 to 5 mm.

2. Accommodation: Look for the eyes to move inward toward the nose.

3. Look to see if there are any changes in the pupil. There should be an obvious change in pupil size from regular to dilated to contracted when presented with light.

Accommodation Test Hold your penlight in front of the child’s nose a couple of feet away. Bring the penlight toward the nose to see if the child’s eyes move inward toward the nose.

Flashing Test Slowly shine the light in one eye, then the other, alternating from one eye to the other a few times. Check for pupil changes similar to the images below.

Vestibulo-ocular Reflex Test

1. Have the child look at a target, such as your penlight, a marker, or a sticker placed on a pencil.

2. Ask the child to look at the target while moving their head to maintain their gaze as the target is moved.

3. Move the target from left to right, up and down.

4. Observe the child’s ability to maintain their gaze on the target. The eyes should move in the opposite direction of the head movement.

5. Repeat the previous steps and ask the child to not move their head while following the target with their eyes.

6. Observe the child’s ability to maintain their gaze and follow the target without moving their head.

7. Difficulties with any of the previous steps may indicate challenges with maintaining gaze, stabilizing eye movement with head positioning changes, and balance.

Part II: Heart and Respiratory Rate Have the child sit, and obtain their baseline breathing and heart rate. Avoid recording this information just after activities of high arousal or when the child is tired. Use the heart rate monitor device, if available, to gather the needed information. If you are using a stopwatch, obtain the pulse rate with the help of a knowledgeable professional. You can then use the stopwatch to record a 60-second interval, during which you should count the rises and falls of the child’s chest during breathing.

Use the following chart as a guide for typical respiratory and heart rates. Being below or above the ranges may indicate the child’s arousal level. If you desire, heart rate and respiratory recordings can be performed before and after attempted self-regulation activities. This information may provide additional information regarding the child’s reaction to certain techniques.

| TYPICAL RESPIRATORY AND HEART RATES IN CHILDREN | ||

| Age (years) | Breathing Rate (per 60 seconds) |

Heart Rate (per 60 seconds) |

| 1–2 | Approx. 22–37 | 98–140 |

| 3–5 | 20–28 | 80–120 |

| 6–11 | 18–25 | 75–118 |

| 12 and older | 12–20 | 60–100 |

| Adapted from Novak, C., & Gill, P., (2016). Pediatric vital signs reference chart. PedsCases.com. Retrieved from http://www.pedscases.com/ pediatric-vital-signs-reference-chart | ||

ANIMAL ASSESSMENTS FOR LITTLE ONES

AIM To help identify the child’s typical arousal and threshold level

POSITION AND ENVIRONMENT Well-lit room with an open area in which to move around

To start, you will need to describe the following animals and their characteristics

• Kangaroo: Likes to hop around and move and go on adventures

• Armadillo: Moves quickly and does not like to be touched or loud noises; it protects itself from other animals and things that are around it

• Hippopotamus: Moves slowly and is sometimes clumsy

PART I

Ask the child the following questions, then have them act like the animal discussed. Clarify the appropriate movement if they do not do it correctly.

1. How do you think a kangaroo moves? Show me (i.e., hopping around).

2. Do you know what an armadillo looks like? How do they protect themselves? Show me (i.e., balling their body up on the floor).

3. What does a hippopotamus look like, and how does it move? Show me (i.e., walking around slowly).

PART II

Ask the child the following questions

1. Which animal are you most like? Or, are you not like any of the animals we discussed?

2. Would you like to be a different animal? Which one?

Look for challenges in the child’s movement or willingness to participate. The verbal and observable information shared may indicate their sensory preferences. “Kangaroos” may have high arousal levels and crave movement and a lot of self-initiated sensory input. “Armadillos” may be overresponsive and avoid sensory input and dislike engagement. Their arousal may be high, but their threshold is low. The “hippopotamus” may have challenges moving and avoid or have challenges with physical activity, handwriting, and self-help tasks. Their arousal and threshold levels may vary.

ASSESSMENT FOR NONVERBAL CHILDREN

AIM To help identify the child’s typical arousal level in addition to sensory preferences

The following are important factors to keep in mind and ways to prepare before beginning the assessment:

1. Acknowledge the level of the child on the Self-Regulation and Mindfulness 7-Level Hierarchy. If the child is at the foundational level, you may need to obtain the following information through observation or caregiver interview rather than through active assessment activities. Printouts can be provided to the teacher or parent.

2. Observe the child during activities of low arousal, such as sitting in class, playing with peers, or eating at the table.

3. Make playing cards by printing images of activities of low arousal, such as sitting in class, playing with peers, eating at the table, sleeping, receiving a massage, or sitting on a bean bag chair.

4. Observe the child during activities of high arousal, such as playing on the playground, engaging in gym activities, or taking movement breaks (breaks from other activities to allow the child to engage in a variety of fast, slow, and cross-lateral movements).

5. Print pictures of activities of high arousal, such as swinging, jumping on a trampoline, dancing, or riding a bike or scooter board.

6. Observe the child during eating. Present them with various food types, such as bland, sweet, spicy, chewy, or crunchy.

7. Print images displaying food types, such as bland starches, sweets, bitter/sour foods, spicy foods, chewy foods, or crunchy foods.

8. Obtain a CD player or smartphone to play music. You will need different forms of music, such as classical, ambient, heavy metal, or rhythmic pop.

9. Gather items of different temperatures, such as ice cubes or heating pads.

10. Please note: These activities most likely will require more than one session. It is preferable to present them in short segments and repeat them on different days. This may assist in gaining a better picture of the child’s overall arousal level versus just getting a “snapshot.”

POSITION AND ENVIRONMENT Can vary

Observe the child in the various scenarios identified in the previous list. Record your observations. Organize an interview with the teacher and/or parent(s). Obtain as much information as possible from those individuals. Have a session with the child, and present them with various sensory stimuli or items described in the previous list. Take note of their responses.

If appropriate, review with the child familiar phrases, such as “I want” or “Give me,” or gestures, such as shaking their head “yes” or “no.” Then, work with the child using your selected method and make note of what they prefer; for example, show them cards depicting low- or high-arousal activities and ask them to gesture “yes” or “no” to show which they like better. You can then use a similar process to assess their preferences for stimuli such as music and temperature. Develop a sensory chart similar to the one provided on the next page to record your findings.

Work with your team to provide preferred stimuli to the child while also attempting to present some non-preferred stimuli to build flexibility. Remember that children will use behaviors and seek stimuli that they believe work best. They may rely primarily on one system, such as movement or proprioception, to block out undesired stimulation. The things they prefer provide comfort. While those items may be useful, we need to be sure to present novel items in a nonthreatening fashion to expand the child’s repertoire. The activities for the various targets outlined in later chapters can be helpful in this process. You may find it helpful to complete a chart such as the following to record the child’s sensory preferences.

| SENSORY STIMULATION PREFERENCES | |||

| Notes | Yes | No | |

| Movement | |||

| Food | |||

| Music | |||

| Temperature | |||

WATER ASSESSMENT

AIM To help identify the child’s typical threshold and arousal levels and stimuli supporting or impeding their function

YOU WILL NEED

• To select the environment (i.e., home or school) about which you will ask the child during the activity

• 5 disposable cups

• Marker

• A container of water

• Food coloring (optional)

• Measuring cup or large cup

POSITION AND ENVIRONMENT At a tabletop or flat surface in a well-lit room

PART I

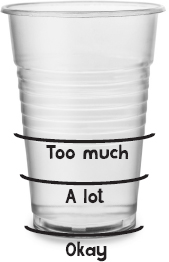

Use the marker to label levels on each of the five cups with “Okay,” “A lot,” and “Too much” and to mark the large cup or measuring cup with “My arousal.” Make three lines on the large cup labeled “Low,” “Medium,” “High”. Provide the child with water, which can be clear or colored with food coloring. Read the child the following questions and ask them to pour water into each cup to reflect their answer. (You can select your own questions or modify the ones provided as needed.)

1. In your classroom (or at home) describe the noise.

2. Describe the lighting in your classroom (or at home).

3. Describe how comfortable the chairs are in your classroom (or at home): Are they okay, pretty uncomfortable (“A lot”), or very uncomfortable (“Too much”)?

4. Describe the smells in your classroom (or at home).

5. Describe the sitting time (length of time you have to sit in a chair) at school (or at home).

Have the child pour the water from each cup onto the large cup (or measuring cup) labeled “My arousal” and see what level the water reaches (“Low,” “Medium,” or “High”).

PART II

Now, write “A little,” “Somewhere in the middle,” and “A lot” on the five cups (or on new cups if the previously used ones cannot be reused), and ask the child the next set of questions, having them pour water into the cups again. As before, these questions can be modified if needed.

1. How much noise do you prefer?

2. How much light do you prefer?

3. How long do you like to sit?

4. How much do you like to smell things?

5. How soft of a seat do you like to sit on?

Relabel the large cup (or measuring cup) with “My threshold” (or use a new cup if the previously used one cannot be reused). Pour the water from the five cups into the large cup and see whether the water reaches “Low”, “Medium,” or “High.”

Talk with the child about the differences between what they like and dislike and what they experience in the various situations that relate to the questions. Have the child use the SAM box radio dial on page 42 to illustrate how they feel (“Quiet,” “Middle,” or “Loud”) when they experience the items presented in the questions. This information helps indicate the child’s threshold and arousal level. Such details can inform you when you are selecting target activities provided in this program.

WHAT PLANT ARE YOU?

AIM To help identify the child’s typical arousal level and methods to support sensory needs

YOU WILL NEED

• To have the child complete the water assessment

• To discuss with the child what plant is more like them (i.e., orchid, fern, cactus or aloe plant)

• To obtain the plant (optional)

POSITION AND ENVIRONMENT Can vary

PART I

Are you a(n) … ?

1. Orchid—particular about the amount of water and light needed; may need the support of a stick to hold it up; needs a lot of care

2. Fern—needs lots of water, humidity, space to move; needs medium level of support to thrive

3. Cactus or aloe plant—survives in most conditions with small amount of care

ASK THE CHILD TO DISCUSS THE FOLLOWING

• How would you care for your plant?

• Discuss what they need every day.

• What do you need every day?

• If you are not getting enough of what you need, how can you fix that?

• What are some things you can do in school or at home?

Refer to the target activities of this program.

PART II

Optional Mindfulness Component

While caring for your plant, simply care for your plant. You can talk to the plant but not to others in that moment. Try focusing on your plant and nothing else! Be mindful of how you care for it. This is a daily exercise that should be practiced consistently.

BONUS Compare the child’s results with your own! How are you similar? How are you different? How do you think this affects your interactions with the child? What changes can you make?

METRONOME ASSESSMENT

AIM To help identify the child’s typical arousal and threshold levels to inform methods to enhance self-regulation

YOU WILL NEED

• To select the environment (i.e., home or school) about which you will ask the child during the activity

• A metronome or a metronome app on your electronic device (which can be obtained for free in most cases)

POSITION AND ENVIRONMENT Well-lit room

PART I

Choose an environment to discuss (e.g., home, school, playground) as well as specific scenarios. You can choose scenarios such as bedtime, sitting in class, or going to the playground. Review how the child normally feels in those environments. Ask them questions relating to the following elements of the scenarios chosen:

1. How does noise make you feel?

2. How does light in the space make you feel?

3. How do you feel when you are sitting?

4. How do you feel when you are moving?

5. How much do you like to smell things?

PART II

Show the child that a fast-moving metronome can be an example of how our bodies feel when we are not comfortable or became nervous or scared. Then, show them that a slow-moving metronome is similar to how our bodies feel when we are tired or bored. Use the metronome to have them represent how they typically feel in those environments and scenarios. Review the obtained information regarding their arousal to select target activities within this program.

OLDER CHILD SELF-ASSESSMENT

AIM To help identify the child’s typical arousal and threshold level and teach them about their sensory preferences supporting or impeding daily function

YOU WILL NEED

• A pencil and paper (optional)

• List of provided questions

POSITION AND ENVIRONMENT Any environment that is comfortable for the child

PART I

Ask the child to complete the list of inquiries on page 58. Follow with a discussion about how certain environments and sensory stimuli can help us get through our day or make it challenging. Explore how the child can use that knowledge. Lastly, use the information gathered to select among the daily target activities that are provided in later chapters.

1. I would best describe myself as: (circle all that apply)

a) Enjoying a lot of activity (e.g., movement, running, jumping)

b) Avoiding physical activity

c) Being a thrill-seeker (e.g., enjoying climbing)

d) Disliking loud or irritating sounds (e.g., other people talking)

e) Disliking certain lighting, such as the lights at school

f) Preferring to wear only one type of clothing (e.g., sweatpants)

2. I would describe my eating and appetite as follows: (circle all that apply)

a) Sometimes I have difficulty knowing when I am hungry until the last minute.

b) I am always hungry and/or thirsty.

c) I only like certain foods and am somewhat picky.

3. I would describe my bodily functions as follows: (circle all that apply)

a) I often have to use the bathroom and have to rush to get there in time.

b) I do not have to use the bathroom often.

c) I do not like using the bathroom (because ________________________).

d) I often feel my heart racing.

e) I often breathe quickly or heavily.

f) I do not feel my heart race or breathe quickly.

g) I do not like a lot of movement.

4. I am a daydreamer (e.g., my thoughts drift off in class). Circle Yes or No

5. What bothers me the most while in class is:

6. What bothers me the most while in public is:

7. What makes me feel better when I am upset, said, or irritated is: