An Australian backyard is the cradle of invention, each with its own cricketing eccentricities. The backyard in East Street opened onto low-lying paddocks that would swamp up in heavy rain. A bowler had to start his run-up at the chook pens and turn a hard left to bowl to a batsman who was up against the back of the house by the barbecue.

JASON AND PHILLIP DEVELOPED a scoring system that made the most of the available architecture and impediments. A shot into the back fence was four. Over it and into the paddock, six and out: get it yourself and start bowling.

The garden bed where Phillip had played with his Tonka trucks was two, the side fence the same. At mid-wicket, the clothesline was 25 on the bounce but 50 on the full. Nick behind and ‘auto wickie’ took the catch, unless you edged it onto one of the narrow veranda poles; then the catch had been spilt and the boys would cry, ‘Taylor’s dropped him!’

Every game was a Test match and Mark Taylor was the slipper. He didn’t drop many. The chook pens, which were at mid-on to a left–hander, were also four. The younger brother’s cut shot was fed, but gained him only two runs, so he learned to work his drives toward the fence at mid-off where he could get four. You can still see the indentations at the point where he pasted ball after ball onto the off-side.

Some afternoons, Greg would let the chooks roam. A chook was 25 runs, an unfortunate bounty for one bird whose life ended when it got in the way. The luckier Hughes birds won prizes at the local agricultural shows, and the boys were given their own.

Every element of the Hughes’s backyard was a scoring opportunity. The fence was two runs, the shed was four, the Hills Hoist was 25 on the bounce and 50 on the full. Phillip’s chickens, once worth 25 runs for a direct hit, still roam nervously.

The Hughes family fence still wears the dings from Phillip’s cut shot.

Competition was fierce between the brothers, the way it has been since Cain sent Abel in to bat, but the toss was a waste of time.

‘He always batted first,’ Jason says without rancour.

A bat was flung into the air and fell ‘hills or flats’. If Phillip lost the first toss, he would call for best of three. If the next, it was best out of five.

‘And if I won again,’ Jason says, ‘he would be like, “Mu-um! Mu-um!” and Mum would yell out, “Jason, Phillip’s batting!”’

Jason would push off the chook shed, turn hard left and the game would begin. Behind Phillip, above slips to the left-hander, were windows. Were. He didn’t mind lofting one over the cordon. While he usually got away with it in a game, in the backyard it resulted in shattered glass and exasperated parents. Virginia replaced that window a number of times and then gave up; the remaining glass was eaten away by cricket balls, shard by shard, until Megan, preparing for her eighteenth birthday party in the backyard, demanded that the window be fixed.

•

PHILLIP WAS FIVE WHEN he first made the papers. He was photographed with Greg, winner of Most Successful Exhibitor at the Nambucca River Show in 1993. A tough man to beat, Greg had previously won Best Commercial Bunch – Irrigated, Best Two Commercial Bunches, Heaviest Bunch of the Show (49.4 kg), Champion Bunch, Three Williams Hands and Heaviest Hand of Bananas.

‘Greg, following in the footsteps of his father, has been growing bananas for 11 years,’ the local paper reported. ‘Greg leaves home for the plantation at 6 am every day and comes back at 4 pm. Part of his work includes cutting bananas once a week, every week.’

Following Jason, Phillip started at St Patrick’s Primary School at five. Mitch Lonergan, whom he first encountered in the maternity ward, also made the journey across town and up the hill to St Patrick’s, part of a rolling wave of boys obsessed with rugby league and cricket in East Street. Every few years, younger brothers joined the pack and were initiated into the ways of the bigger boys: the Lavertys, the Lonergans, the Ramunnos, the Martines, the Wards, the Hugheses and more who biked in from nearby. There was hardly a girl in sight, although cousin Sharnie rolled up her sleeves and joined in. They say she was tougher at football and more skilled at cricket than any of the boys.

The games advanced from one backyard to another and sometimes into the paddocks of the Donnelly Welsh Playing Fields. Each yard had its own cricket rules, but only the Hugheses’ had lighting that allowed the game to roll on after sunset, only winding up when the last kid was summoned home for bath and bed.

If they weren’t kicking or hitting a ball, they were riding around Macksville. Mitch Lonergan remembers going ‘to town to get lollies . . . There were a couple of ways to go up to town. The first street, which was the quickest way, had magpies in two big trees. [Phillip] loved the thrill of the magpies chasing and swooping, but I was too scared and couldn’t go that way, so I would go the longer way and had to meet him up town.’

The Hughes children’s godparents, ‘Uncle Winston and Aunty Kay’ Clews, lived between Taylors Arm and the Tilly Willy Creek a couple of kilometres away. Winston had built a retaining wall by the river known as ‘Winston’s Wharf’, a favourite fishing spot for the Hughes boys and their friends. There were rumours of a giant groper that lived beneath the bridge, one the kids dreamed of landing.

‘He was competitive at that again,’ Jason says. ‘He would try and catch the biggest fish, but he wasn’t really patient and after a few hours he would ring Mum to pick him up.’

To this day the groper remains unharmed, but the boys landed just enough smaller fish to keep coming back.

The kids from the area made Winston’s Wharf their second home. Kay would bake cakes for birthdays, while Winston baited the hooks and freed the snags. Sometimes he took the kids out on his boat. Phillip would never forget the important people in his early life. Much later, he always visited the Clewses when he was back in town, or called them when he was away. When Winston got cancer, Phillip, by then a Test cricketer, dropped in with a signed cap and when Winston passed away, wore a black armband in the New Year’s Ashes Test match at the Sydney Cricket Ground.

Uncle Winston and Aunty Kay Clews’ beautiful backyard led to a wharf on the river where Phillip and Jason spent many hours fishing.

Kay never cared for cricket, but became infatuated with Phillip’s career. ‘I would get so excited when he came on the news – I would jump up and down and kiss the telly,’ she says.

Phillip gave her a coffee mug with his face and his shirt number, 64, on it when he returned from an Indian Premier League stint with the Mumbai Indians, another prized possession but no more prized than the memories Aunty Kay keeps of the chubby little boy with blond locks and cheeky smile.

Gatherings of family and friends usually took place at home. Aunty Kay’s birthday cakes were the centrepiece of parties where the house was thrown open not only to the kids and their friends, but to the extended Hughes–Ramunno clans. ‘We always had their birthday parties at home and they were lovely times,’ Virginia says. Day-long Christmas barbecues took place in alternating years either at home or at Greg’s parents’ house. ‘Phillip was happy with whatever presents he got, and he loved Christmas,’ Virginia says. ‘There was a lot of food, all the cousins and aunties and uncles were there, and before long there would be football and cricket set up, with everyone playing.’

Country life could never be too white-bread with the Ramunno connection. Virginia’s mother Angela, or Nan’s, riverside home is decorated in the mid-century Italian style, the front room bursting with ornate furniture, porcelain figurines and a wall covered in family photos, a slice of the old country in the heart of the new. Angela spoke both languages but favoured Italian around the family. The kids picked up enough words to understand her and insult each other.

‘We have little words we would speak and continued for years to talk Italian to each other and we had Italian nicknames for each other,’ Sharnie says. ‘We probably don’t really know what we mean.’

A traditional matriarch, Angela, or Nan, could be found mixing flour and eggs for fresh pasta and making Italian dishes every day in her ‘pasta room’ at the back of the house. The kids were encouraged to join in, and would get covered in flour and red sauce. Grandchildren on their way home from school gathered around the big table where dough was pressed and cut by hand or machine, and mixed with sauce made from Nan’s home-grown tomatoes and herbs.

Sharnie, the daughter of Virginia’s brother Geato Ramunno, who also lived on East Street, remembers getting in trouble for eating pasta raw. Nan was not a woman to meddle with, but Sharnie says Phillip had his way with women from a very early age.

‘Boof got pretty much what he wanted from Nan – he was a smooth talker. Sometimes we would ask, “Nan, why are you making that type of pasta?” and you would see Boof laughing in the background. He was pretty cheeky that way.’

Jason recalls his younger brother loving Italian food. ‘I wasn’t a massive fan, but Phillip loved it. Loved it. There were days when he would go, “Oh Mum, could you get Nan to cook me this or that?” and she’d just do it. Bolognese, pizza, pig’s trotter . . . Phillip loved his Italian because the only other exotic restaurant was the Macksville Chinese. He moved to Sydney and he didn’t know what was going on, didn’t know you could go out for Indian or Thai. We didn’t have those things.’

If Phillip got his way, it was because he had a charm that even an older brother couldn’t deny.

‘We did fight sometimes,’ Jason says, ‘but I reckon we have to be up there with the closest brothers going around. You just couldn’t dislike him, you just couldn’t. He had so much going on for him, and he just got what he wanted. When he was young, Mum gave him everything, but she was the same with all of us. She was good, Mum. There were a couple of times where we’d just have a day off school and Mum would take us to Coffs for new Nikes. If Phillip wanted them, he got them. Mum just said yes.’

Phillip adored his mother, and Virginia admits that he got his way too easily. He never had to ask; he just had a way of flashing that smile, twinkling that eye.

‘Even when he’d left home,’ she says, ‘he would call if he needed something. If Greg answered, he’d say, “Dad, I don’t need to speak to you, I want Mum on the phone”. He would say Mum, Mummy or Vinny, and I knew straightaway what he wanted. All the kids were the same, they all came to me . . . He just had a tone of voice . . . He would never say, “Mum, I want money”. He knew how to swindle, it was just a way he had. I’d say, “Okay, it’ll go in today”. But there was no mention of money. I could never say no to him.’

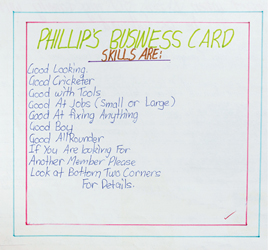

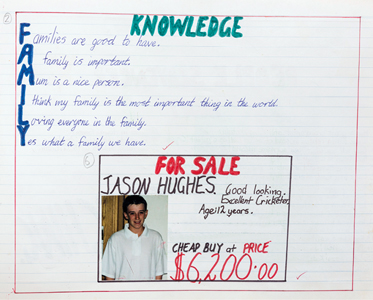

When he was ten, Phillip did a school assignment on the family. The work reveals a deep bond of love that is craftily manipulated for the task. Nan is in an ‘advertisement’ section that reads: ‘Come one, come all, come and visit your elderly relatives. Pop in: Have a Cuppa: Have a chat: Have a hug but most of all come in and visit anytime. Family always welcome.’ The words are arranged around a picture of Angela. Part of the task asked the students to imagine where they would be when they were 30. It’s sweet and heartbreaking at the same time.

Phillip won Champion Junior Boys Swimmer at St Patrick’s. Swimming was a talent he picked up from his mum, Virginia. Phillip said: ‘Mum tells me think positive and you will always do well.’

Fishing from the Macksville Bridge, Nino Ramunno remembers little Phillip almost going over the guard rail as he hooked a big jewfish. ‘I ran over to help but Phillip stopped me in my tracks with an intense look of steely determination in his eyes. There was no way he wasn’t going to land that monster all by himself. And he did.’

Christmas Day is a big event in the Hughes household. Phillip was always the last one to go to sleep and the first one up. Greg, Megan, Phillip and Jason sit among the wrapping paper where Phillip had just unwrapped his beloved Tonka crane.

Virginia, who was working at a chemist’s, drove him everywhere and passed on her talent for swimming. ‘Mum tells me think positive and you will always do well.’

Dad is his cricket coach, Jason is a ‘great mate’ and bowls to him ‘all the time, he has helped me to become a great open[ing] batsman in cricket’. Megan is too young and ‘really hasn’t helped me in anyway as yet . . . but I love her anyway’.

Megan was just two when Phillip did the assignment, but they would strike up a special relationship.

‘He called me Mego or Sis,’ Megan says. ‘Everyone calls me Mego because of him. I don’t know where that came from, I guess one day it just rolled off his tongue. Outside he was Phil, Hugh or Hughesy or something, but at home he was Bro or Boof, because when he walked through that front door from being away I wanted him to feel at home again.’

Like Jason, she says he was too lovable to argue with. ‘You struggled to stay angry with him; he would always make you laugh and stop being angry. If he was irritating me, not making me angry, just playing with me, I would go, “You’re annoying me, Bro”, and the next minute he would do something funny and it was totally gone. I could not stay angry, he had the most beautiful heart.’

When the boys were young, Sharnie, already at high school, would look after them until Virginia got home.

‘We were together every day, basically playing football,’ she says. ‘Cricket started really creeping in when Phillip was around eleven or twelve, and it changed from backyard football to backyard cricket.’

Phillip adored his younger sister, Megan, or ‘Mego’. He used to hug and squeeze her until Virginia would tell him, ‘Put her down!’

The cover drive was born at home because it was worth double, but at the Ramunnos’ the rules were different.

‘That bloody cut shot,’ Sharnie says. ‘That’s where he got it from. He would stand there the whole time. Cut shot, cut shot, cut shot, cut shot . . . until he got a hundred. And we were like, “Seriously, we can’t get this bugger out”. Sometimes we were glad when it was too dark to play because that was the only way to stop him.’

If it rained, Sharnie and the boys went inside and played ‘classic catches’, which involved kneeling on the carpet and pinging a cricket ball to an opponent also on their knees. Many a vase paid the price for not such a classic catch. China, windows, tin fences and chickens all paid the price for the cricket obsession that gripped the East Street kids.