The South Africans regained some face with a win in the third Test match in Cape Town – Phillip scoring a brace of 30s – but the Australians were already in celebratory mode before leaving Durban.

‘ONE OF MY BIGGEST regrets is staying home and not going out with them,’ coach Tim Nielsen says. ‘They had a ripping night: I remember the camaraderie, the gleam in their eyes, and Hughesy was right in the middle of it.’

Ponting ranked the 2–1 series win among the best of his seven-year Test captaincy and, given his inexperienced personnel, the location away from home, and the quality of an opponent who had so recently beaten Australia in Australia, he would be justified in placing this on a pedestal above the Ashes whitewash of 2006–07.

Much of the attention in what appeared a sudden and unexpected Australian renewal was focused on Johnson, who was named the ICC Cricketer of the Year, and Phillip. Both had unusual techniques and, in both cases, the praise would be mixed with a picking-apart of their styles and a rising debate over whether they would succeed on the coming Ashes tour of England. Phillip was set for a rigorous examination by bowlers and commentators alike.

His defenders rallied in advance. Justin Langer still rates Phillip’s batting in South Africa in 2009 as one of the best achievements he has seen in cricket. ‘They were saying he couldn’t play the short ball ahead of the second Test in South Africa, and he got those hundreds. Unbelievable: he just kept grinning at them. They were baiting him in the press conference before the game and at him out there, but he just kept grinning. They were the best fast bowling attack in the world and he got a hundred in both innings. That was freakish. Seriously mate, that is Muhammad Ali stuff.’

Clarke says, ‘He loved that they thought they had seen a weakness. Scoring runs was in his genes, in his blood, and he adapted to anything and didn’t care what he looked like.’

But others did care, so much so that ‘experts’ on technique viewed Phillip’s achievements as something of a fluke, disregarding that he had been piling up runs in this style all his cricketing life. As debate grew, the Australian’s Malcolm Conn approached the high priest of correct batting technique, Greg Chappell, who gave a stern rebuff to questions about Phillip’s footwork against fast short-pitched bowling.

‘It’s the way Bradman countered Bodyline,’ Chappell said. ‘There’s no right way or wrong way. Have a look at the scoreboard and tell me that he’s played badly. He doesn’t comply with the coaching manual, but the coaching manual should have been burnt before it was even published, because it’s been the greatest impediment to exploring batting in its fullness that’s ever been perpetrated on the game of cricket. The better players have not necessarily fitted the coaching manual. To focus on replicating the perfect cover-drive actually misses the point of what batting’s all about. You don’t want to hit the ball in the same way and in the same area all the time. Phillip has his own method and who’s to argue with it?’

A gleeful D’Costa told journalists, ‘I can show you a player that the traditionalists would love. He’s averaging 21 in grade cricket.’

Six years on, D’Costa still adheres to the view that the discussion of Phillip’s technique was irrelevant. ‘My job was to get out of his way, keep the road clear for him and keep other people out of his way. He was a batting genius. You just had to set the right environment, a few tips, and keep people out of his way.’

In his post-South Africa interview with Mike Coward, Phillip explained: ‘You get a few coaches who like to change a lot of different things, but my own personal coach, Neil D’Costa, he’s been great. Obviously we’re always working on my game and keep improving it . . . but overall you’ll keep what you’ve been natural at.’

Tim Nielsen, who had overall charge of Phillip as Australian head coach, says that nothing was said to him during the tour by the coaching staff about his technique, and that the sanctum of his personal relationship with D’Costa was respected.

‘People had always spoken about him playing differently,’ Nielsen says. ‘Our biggest thing was, “Don’t doubt yourself, mate, you’ve played this way to get here”. The thing is, all players are going to be on their own when they’re out in the middle. Our approach was to get them thinking about things that might happen, so that when they are confronted with it it’s not the first time they’ve thought of it. So when the South Africans set him nine gullies, eight slips and a couple of deep backward points, he’d anticipated that. He’d always had it. And they still couldn’t get him.’

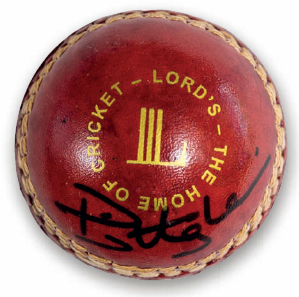

Phillip came home and visited family and friends in Sydney and Macksville, where an award for a promising young local cricketer was named in his honour. He prepared to leave for England, not for the Ashes yet, but instead for a one-month county stint with the Lord’s-based Middlesex club, where he would reunite with his former underage teammate Sam Robson.

Middlesex’s director of cricket, former Test bowler Angus Fraser, had signed Phillip before the South African tour as cover for the county’s Indian overseas player, Murali Kartik.

‘It was seen as a left-field signing at first,’ Robson recalls. ‘Often overseas players had been Test players, so he was an unusual signing.’

Although he had not played in England since the NSW Youth tour in 2006, Phillip adapted with stunning speed. In his first county championship game, at Lord’s against Glamorgan, he struck 118 from 169 balls in the first innings and an unbeaten 65 off 72 in the second. His other county innings were 139 against Leicestershire, and 195 and 57 against Surrey: a return of 574 runs at 143.5. No Australian 20-year-old had hit England with such figures since Bradman. Phillip was less successful in the limited-overs format, but finished his stay with a one-day century and a 50 at Lord’s.

‘Everyone was in awe of the way he played,’ says Robson, who was in the Middlesex Seconds, having elected to pursue his future as an England player. ‘But he was just the same as ever. We hung out together like nothing had changed.’

Phillip came back to Australia to prepare for the Ashes, and impressed his teammates with how little he had changed. He had been preparing for this since such a young age. The low-key maturity – telling Daniel Smith ‘That’s Test cricket’ when he had only played one innings – now seemed to make perfect sense.

‘Some days I still wake up and think to myself how good it’s been,’ he told Mike Coward. ‘It has been a dream, it has happened very fast. But it’s something I’ve always planned for too.’

What happened next was certainly not part of the plan. In retrospect, his first stint in Test cricket seems to have been played in fast-forward: the fourth-ball duck, the plundering of the South African bowlers, and then the downfall. While the suddenness of Phillip’s success at Test level set new records and captivated the cricket world, the rapidity of his demotion was equally stunning.

In the way memory warps perceptions of time, observers will recount how Phillip lost his way against around-the-wicket, short-pitched fast bowling in England in 2009, before being put out of his misery by merciful selectors. The fact is that Phillip did not have any prolonged form slump. He only played five matches over the course of four weeks on that tour. In the first, he made 15 and 78 against Sussex. He then had two single-figure scores against the England Lions at Worcester, where the awkward high action of Test bowler Steve Harmison made his dismissals look ugly.

Teammate Shane Watson, who had only seen Hughes from across state lines in the Sheffield Shield, recalls that Hughes was still batting well in the nets. ‘I remember bowling to him and I thought, “My God, this guy has got his game sorted.” Everything hit the middle of his bat – defence, attack, everything.’

In the first Test match at Cardiff, he made 36 in an hour, and in the second, at Lord’s, a match in which only Clarke mastered the England bowlers, he scored four and 17. His family went to England to watch those two Test matches. In the second innings at Lord’s, Greg remembers Phillip surviving for 45 minutes against Flintoff before edging the ball just short of Andrew Strauss at first slip. ‘The television replays showed that it didn’t carry, and Ricky Ponting was begging the umpires to go upstairs for a review, but they wouldn’t.’ Immediately, Greg’s phone began to fill with outraged texts from friends. ‘We were all disappointed. It shouldn’t have been given out, and if it hadn’t, who knows how many he’d have scored?’

The umpiring error proved to be a turning point in Phillip’s life. In the next match against Northamptonshire he scored ten and 68. He was not setting the world alight, but he had every right to expect to play in the third Test match at Edgbaston. He had planned for this very game, hitting a hundred at the ground for Middlesex, as he had planned ahead by playing Surrey at the Oval, the venue of the fifth Test match.

The day before the Edgbaston Test match, duty selector Jamie Cox knocked on Phillip’s hotel-room door. ‘It was a short conversation,’ Cox recalls. ‘I told him the reasons we were leaving him out of the Test. We had concerns about the way Harmison and Flintoff had got him out, and it wasn’t a decision we’d taken lightly. He was fine – obviously disappointed, but he wasn’t going to drop his lip.’

Phillip had been dumped. The outside world learnt just as abruptly, via the social-networking site Twitter.

‘Disappointed not to be on the field today,’ D’Costa, on Phillip’s behalf, posted on match morning. ‘Will be supporting the guys, it’s a BIG test match 4 us. Thanks 4 all the support!’

Here, too, Phillip was a ground-breaker. Not knowing that the team was not yet publicly announced, he was reprimanded for the breach of protocol and was responsible for a ban on such use of social media by players. There was an irony in this, as Hughes was not a social-media devotee, and rarely sent emails. A brief but affectionate note to D’Costa in 2011 was, he wrote, the ‘first email I have ever sent mate hahahahahaha’.

When Ponting and Nielsen explained Phillip’s omission (though neither was a selector), they offered him a number of interpretations. There was a desire to protect him from a prolonged working-over. He found Flintoff’s action from around the wicket particularly difficult, as had other left-handers including Adam Gilchrist, Justin Langer and Matthew Hayden. There was a belief among selectors that Phillip’s confidence was brittle, and that he needed to be shielded from the trauma of being picked apart in England. Nielsen, who consulted Cox before a phone hook-up with chairman Hilditch in Australia, says, ‘The selection panel was thinking about the long-term impact it could have on him. When he’d made runs on the tour, the execution wasn’t convincing.’

‘Sometimes,’ Cox says, ‘it’s important to find the right time to take them out.’

The immediate reasons were also pragmatic. In Cardiff, Australia had failed to close out a win from a dominant position, allowing England to escape with a draw that was as good as a win. At Lord’s, Johnson and the other pacemen had lost their heads on the first day and Australia had imploded. Ponting felt that he needed more bowling options. The selectors wanted a more experienced player of fast bowling at the top of the order.

Not for the first or last time, Shane Watson was seen as the solution. His Test batting average was 19.76 and he had never batted higher than number six, but he had excelled as a one-day international opener.

‘It was no blight on Hughesy,’ says Nielsen, ‘more that we needed to make a change to counter what England were throwing at us.’

Watson took Phillip’s place, and to his credit Watson proved the most stable of the Australian top order in the three remaining Ashes Test matches, scoring 240 runs in five innings, three of which were half-centuries. Watson himself still remembers Phillip’s fall from favour as ‘the biggest surprise of those Ashes’. He only bowled eight wicketless overs. But although Australia’s batsmen scored eight centuries to England’s two and they had the three top wicket-taking bowlers (Hilfenhaus, Johnson and Siddle), they lost the ‘big’ moments at Lord’s and the Oval, and surrendered the urn.

Some of Phillip’s teammates were, and still are, perplexed by his omission. There was an orthodox idea about young players needing time in the wilderness to work on their game and build their resilience to suffering. It had worked for the nucleus of the recent great era in Ponting, Clarke, Hayden, Langer and Martyn. It had worked for Steve Waugh and Ian Chappell, and it had even been used (for one Test match) to harden up Don Bradman.

Ponting says the decision was one of the most difficult during his captaincy, but supported the selectors’ reasoning and experience, and agreed with the view that Hughes’s confidence might be even more damaged by a prolonged exposure to the skilful English pacemen. He felt Hughes’s pain, but says, ‘We had all been there before, many of us at an older age. I had no doubt he would bounce back.’

It was a proven formula. But in this case, was it necessary?

Mike Hussey doesn’t think so. ‘I personally was disappointed for him. I have never liked that selection policy of giving a young player time in the wilderness, because it shows everyone how quickly selectors can lose confidence in you. I was worried about how he would cope in the short term, and in the long term I was worried about how it would affect the team to see someone that good get dropped so quickly.’

Hussey has an explanation for why, in 2009 and also later, Phillip was so often the man to be dropped when selectors were faced with line-ball decisions. ‘His technique might have made him an easy guy to drop. There’s this story they can tell about going back to first-class cricket to fix up aspects of your technique, and when it came to a choice between Hughesy and another guy, they might have thought it was easier to tell that story to him.’

Katich is blunt in his disagreement with the decision. ‘He copped Flintoff at the peak of his powers, particularly in Cardiff. I can remember him bowling absolute pace with the new ball. It was as quick a spell as I have faced, and then at Lord’s once again . . . on a quicker wicket. Hughesy wasn’t the only one to miss out at Lord’s, and that was the last time Freddie bowled at that pace. I thought [it was unfair] because you are looking at a guy who a couple of Tests before had won us a Test series with the way he played at that game in Durban. To be dropped after three innings, to give the side a change in balance, was hard to take from his point of view. I thought it was tough at the time . . . He paid the price for us not being able to finish the job at Cardiff, a Test we should have won and didn’t, through no fault of his. I understand why they did it – he was the fall guy because we needed another bowling option and the other bats were pretty entrenched.’

Phillip did not parade his disappointment publicly or to many teammates. Cox recalls spending extra time talking with Phillip to reassure him that ‘we thought he was a beauty, he would play an enormous amount of Test cricket. To me, he was quiet but very professional in understanding what I was saying.’

Hussey says, ‘He never really showed how hurt he was. Running drinks, he was cheerful, and he was helpful in the dressing room, which showed really good character.’

Even to close friends back home, Phillip was staying bright. He exchanged texts with Peter Forrest, but, says Forrest, ‘I never heard him whinge. I think it was the first time he had been dropped from any team. Right or wrong, it’s hard to take. It’s on the big stage, there’s so much media hype in England, it’s a lot to go through, but he didn’t show much disappointment to me.’

But privately, on the tour, a different story was unfolding.

‘The guys who aren’t playing, you try to spend a little more time with them,’ Nielsen says. ‘I’m sure that he was smiling through gritted teeth. We trusted our senior players a lot and encouraged them to take younger players under their wings.’

Through late nights in hotel rooms, Phillip shared his devastation and confusion with the senior teammate he most trusted, Michael Clarke.

‘Being vice-captain, I had to do what’s best for the team and act like I had made the decision myself, even if I didn’t agree with it,’ Clarke says. ‘I had to be very careful. Being so close to Hughesy, I couldn’t say, “Yeah, I can’t believe they did that”. I said things more like, “What do you want to do now? If you need a shoulder to cry on, if you want balls thrown at you, if you want to go out to a bar, whatever you want, I’ll be there for you”. It was more about moving forward than going over the selectors’ decision.’

Katich took a similar view. Like Clarke, he could offer sympathy and understanding but was mindful of the need to steer him away from bitterness.

‘He took it hard. I said, “If you need to get it off your chest, come to me”, because I had been through it myself and if anyone understood, it would be me. We did talk, and I understood where he was coming from, the frustration of feeling like he hadn’t done too much wrong . . . I think through that period he went out for a few drinks to let off steam, which is fine. That was his way of dealing with it, which is what most blokes do.’

For a player entirely focused on winning, Phillip was doubly disappointed by the loss of the Ashes. The selectors had gambled by leaving him out, and had lost both ways, losing the series and leaving him with a wound that, Katich says, ‘stayed with him’.

When Phillip arrived back in Australia, he found plenty of support, and the solace of friends who could let loose their own anger.

D’Costa picked him up from Sydney Airport and says, ‘it’s the only time I’ve ever seen him upset. This was his dream. To live it and get it taken away so quickly, to see how people changed their opinions of him so quickly, was eating him.’

D’Costa said the experience changed Phillip, not just because he was out of the Test team so soon after his success but because of the difficulty, for a young man who lived and breathed cricket, of spending the last five weeks on a cricket tour not playing matches.

‘He had too much free time after they dropped him. He needed to be kept busy. That 2009 tour, he went weeks without playing. He’d gone from being a star to being a pauper.’

Even in the car leaving the airport, D’Costa set about building Phillip back up, reminding him that he had broken more of Don Bradman’s records than anyone, that he was the youngest player to score twin Test centuries, and that he was the youngest to make a hundred in a Shield final.

‘If he’d been Indian,’ D’Costa says now, ‘he’d have played every Test and never been dropped, they’d have found a way. It was a disgrace what they did to him.’

In the days after his return, Phillip reconnected with his closest friends. Some tried to steer the talk away from his omission.

Daniel Smith says, ‘If we were at a pub or cafe, we were talking about life, not cricket selections. He had that segregation between the two. He was a deep thinker about the game, but didn’t harp on it 24/7. I saw my role as getting him thinking about something different instead of dwelling on why he’d been dropped. That would only make it worse. I knew he was hurting, but I also knew he was going to get back up and score a lot of runs.’

After an introduction through Brett Lee, Phillip had also begun to seek the counsel and mentoring of radio announcer and former rugby coach Alan Jones. They would communicate by text, Jones sending motivational messages, and sometimes Phillip would drop over at Jones’s waterfront apartment overlooking Sydney’s Circular Quay.

‘Even if I was busy, he would happily sit on the veranda with his form guide saying he was “trying to pick a winner in Muswellbrook,”’ Jones says. ‘Of course, Muswellbrook was a metaphor for trying to pick a winner anywhere.’

As their friendship grew over the years, Jones would find Phillip an inquisitive young man who ‘wanted you to open up and do the talking. He loved to ask questions. I can still see him standing on the veranda. He was fascinated by so many things – he wanted to be worldly and couldn’t learn fast enough. They were precious times.’

When they talked cricket after the 2009 Ashes tour and during the next few years, Jones would pump Phillip up by saying, ‘Worry about the next one, not the last one,’ or relating stories of unorthodox geniuses such as the great left-handed Test opener Arthur Morris. ‘I think he trusted me because I’d had some success on the coaching front,’ Jones says. ‘I’d just say, “You can’t play contrary to your personality.” Or when there was criticism, I’d say, “You’ve got two ears. Let it go in one and out the other.” I think he was happy to hear that.’

Jones urged Phillip not to change his style in response to being dropped. ‘As a sportsman, he was not conventional,’ Jones says. ‘By dropping him, they made the risk of telling him that the way back was by becoming more conventional. I just said, ‘It’s served you in the past, it will serve you in the future.’

Phillip made light of his troubles in his inimitable way. Inviting his close friends to his home to cook for him, he would re-enact games in his lounge room, his bat waving around like a sword. He said that facing Andrew Flintoff had been like having your back against the fence and someone playing brandings, hurling balls at you. He turned the experience into a high-spirited comic routine, making his friends laugh by exaggerating the scenario.

‘I looked at Kato for help and he gave me nothing – he just looked the other way, and when I wanted to run, he wouldn’t back up!’

Already, Phillip was thinking about forcing his way back in. He spoke to his state coach, Matthew Mott, and expressed his disappointment. There was a lot of talk about international bowlers ‘working him out’ and denying him balls to cut, but Phillip had not been in any prolonged streak of bad form.

‘It’s toughest when you get dropped and you feel like you’re going OK,’ Mott says. ‘Flintoff’s bowling had put the spotlight on his technique. He started to question his own method for a while.’

Dave O’Neil, his club president at Wests, met him for coffee at Concord and suggested that he talk with Ponting.

‘He was dropped about three times early in his Test career.’

Phillip wasn’t sure about approaching the captain.

O’Neil said, ‘Wait till you play Tassie and talk to him then, but in the meantime just put your head down and make runs.’

Which was exactly what he did.

First, though, he needed to go to Macksville and rally with Greg, Virginia, Jason and Megan, and with his close friends in the town. He said to Smith, ‘Braz, I’m going home to play with the cows a bit.’