1

A Matter of Foundations

At the Ara Pacis Augustae – Romulus and Remus – Aeneas and the Origins of the Romans – Foundations – Archaic Rome – The Servian Wall – A City of Seven Hills – The Forum Romanum – From Settlement to City

At the Ara Pacis Augustae

In his biography of the first Roman emperor, the historian Suetonius had Augustus famously observe that he had ‘found Rome a city of bricks and left it a city of marble’: ‘Marmoream se relinquere, quam latericiam acceptisset.’ The year 2014 marked two millennia since the emperor and his marble city finally parted company – the former to enter the afterlife, the latter to continue bearing witness to the passage of time – and the biographer captures perfectly the absolute transformation to which Augustan Rome bore witness. Once the centre of its own world, one settlement among several, it had become the centre of the world.

To mark his achievements in perpetuity, Augustus conceived of three monuments: a domed, circular mausoleum (main map, 2), now called the Augusteum, that would house his funeral pyre (ustrinum) and a dynastic tomb; a massive sundial, the Solarium Augusti, casting its shadow across the Campus Martius; and a monument to the ‘Augustan Peace’, the Ara Pacis Augustae (main, 1), which the sundial would overshadow each year on 23 September, the autumnal equinox and the emperor’s birthday. Each monument entered a state of ruin within the lifetime of the empire Augustus had founded, only to be recovered in piecemeal fashion as the Campus Martius, or Campo Marzio, became increasingly populated with palaces and churches in the early modern era.

Fragments of the Solarium were found from the fifteenth century onwards and placed in their current location before the seventeenth-century Palazzo Montecitorio – once home to the Curia Apostolica and, since Unification, accommodating the Italian House of Representatives (main, 3). Pieces of the Ara Pacis (or what have long been assumed to be such) were also collated from the sixteenth century onwards to form the monument that now sits opposite the forlorn Augusteum, which was restored as part of an urban renewal project conceived under Mussolini’s authority in the 1930s. The bimillennial of Augustus’ death was a dull affair marked by missed deadlines. The 1937 celebration of his birth, however, was vividly coloured by the cult of romanità as ideologues and tastemakers sought to recast Rome as the heart of a new Italian Empire, a natural heir to its ancient imperial forebear. That year saw the inauguration of building works intended to ensure that the Ara Pacis was preserved as a privileged moment within the fascist city – works that were interrupted by war and never resumed. More than half a century later, though, the Ara Pacis found itself encased in a contentious new building designed by the American architect Richard Meier, opening to markedly mixed reviews in 2006.

The significance placed by Mussolini on imperial Rome was hardly the first time that a glorious past had been used to validate present-day claims of authority. Augustus himself built confidently on the bedrock of Rome’s myths – two of which, rendered in marble, we meet upon entering Meier’s stage (figure 1.1). Only with difficulty can we extract the events depicted on the Lupercal and Aeneas panels from the very idea of Rome, and so each deserves our attention.

Figure 1.1: Ara Pacis, building by Richard Meier (completed 2006).

Romulus and Remus

Romulus and Remus are everywhere in this city: twin infants sustained by a she-wolf, one of whom would go on to found Rome itself. The medieval, bronze Capitoline Wolf – with its sixteenth-century addition of the twins – has come to stand for Rome as surely as the Eiffel Tower stands for Paris and the Statue of Liberty for New York. (The eighteenth-century art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann suggested that the wolf was Etruscan, possibly made by the same sculptor, Vulcan of Veii, who carved the reliefs on the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus. Carbon dating has put it instead as being made between the mid-eleventh and mid-twelfth centuries.) In modern times it was used as the symbol of the 1960 Olympic Games and even now appears on the crest of Rome’s premier football team– on almost anything, really, that can be sold at a souvenir stand or market stall. T-shirts, key rings, beanies, barbeque aprons: Romulus, Remus and the wolf, alone in their cave, embody Rome. In the Ara Pacis their story is invoked on the left of the two panels (the Lupercal Relief), which shows the brothers drinking from the wolf in the shade of a fig tree under the protective gaze of their father, depicted as Mars, and the shepherd Faustulus, who found them at the base of the Palatine and raised them with his wife, Acca Larentia.

Standing before the Lupercal Relief is one way to reflect upon this foundation myth. Another is to make the short trek from the Ara Pacis to the Palatine hill (entry through the Forum for a fee) and to the Domus Augusti (House of Augustus: inset map, 33) thereupon, now protected by an incongruous hip roof (and partly visible from the Circus Maximus, or Circo Massimo, that runs along the base of the hill). In 2007, archaeologists announced their discovery of a decorated first-century BC circular chamber beneath the Domus– an apparent celebration of what they claimed to be the very cave in which the twins were said to be raised. It appeared to add substance to the story. Enthusiasm quickly gave way to debate, though, as to the precise identity and patronage of what had first been named the Lupercal, but it is difficult to shake the idea of the emperor literally building his own house upon the embellished grotto in which the idea of Rome was first made possible.

The events held to have followed the discovery of Romulus and Remus on the banks of the Tiber (the course of which having changed over time) comprise what must arguably be one of the best-known stories of antiquity. As is common with siblings, the boys were close, but were also prone to fight, and as they grew into men their conflicts became more pronounced. They were children of the god of war and grandchildren of the king of the principal Latin city of Alba Longa; rulership was in their blood. (Castel Gandolfo, the pope’s summer residence, now occupies the site of Alba Longa.) Before the boys had been born, Amulius had conspired to remove his brother Numitor from the throne, kill his male heir and commit his niece Rhea Silvia to life as a Vestal Virgin. Discovering that she had become pregnant (to the god Mars, she claimed) and given birth to twin boys, Amulius instructed that the boys be killed and their mother imprisoned. The boys, as we know, survived. As youths, they worked the slopes of the Palatine hill and tended livestock, playing Robin Hood in their spare time by depriving thieves of their spoils and distributing the takings among the shepherds. An act of retribution saw Remus in the custody of his grandfather, who (like Faustulus at the same time) did his sums and understood the young man to be his grandson. Romulus and his shepherd brethren met Remus at an agreed-upon time and they together overthrew Amulius, King of Alba Longa.

Not content with waiting to inherit Alba Longa from their grandfather, Remus and Romulus instead embraced the prospect of founding a new city (or two new cities, depending on the account) on the very slopes where they had tended flocks with their adoptive father. Romulus built a wall (or dug a trench) to define the extent of a settlement over which he would rule as king. Remus may or may not have founded his own city of Remoria (main, 31) on the neighbouring Aventine hill, but he insulted Romulus’ fortifications and showed their weakness by climbing (or jumping) over them, at which point either Romulus or his agent Celer (from whom we have Celeres, royal bodyguards) clocked him fatally on the head with a shovel (or a hoe, or some other deadly implement), thereby clearing up the question of sovereignty and defining for the city its first ruler, after whom, naturally, Rome took its name.

This is the most resilient version of events, recorded three centuries after the fact by Quintus Fabius Pictor. Fabius wrote towards the end of the third century BC, in the years of the Second Punic Wars, when Rome had begun to assert itself as a Mediterranean force and acquire colonies. He helped to make sense of the city’s rise and shaped the image that projected its power and authority within the region. The history written by Fabius is now lost to time, but shaped those later histories written by the likes of Polybius, Dionysius of Halicarnassus and Titus Livius Patavinus, known as Livy. Written in the time of Augustus, Livy’s history was called Ab urbe condita (‘from the founding of the city’), borrowing from Fabius to explain the events spanning from Rome’s origins to his present day. As such, his rehearsal of the so-called Fabian myth offers a reassuring version of Rome’s foundations as a city at a time when, under Augustus, Rome was bedding down fresh footings upon them.

Livy has Romulus disappear at the end of his life, being swallowed up by a storm after offering a sacrifice on the Quirinal hill: perhaps an early instance of senatorial regicide, but with the effect of deifying the founder for subsequent generations. Variations on Fabius (and Livy after him) abound, and the now-conventional depiction of the twins, wolf, shepherd and wife is one version of a story told every which way. Some writers accord Acca Larentia with either more base or more divine standing, depending on the storyteller; some conflate her with the wolf. Others have Remus survive Romulus, which would put paid to the Fabian punchline. The importance of the story is not, though, simply in identifying a moment in which Rome comes to be: a makeshift weapon finding its mark and a furrow hitting the earth, first gestures defining the city that would rule the world. It rests rather in the potential authority offered by history to the great families of the third and second centuries BC, whose origins, too, one way or another trace back to the Lupercal. It also lies in the promise of Rome’s enduring power, secured by the bloodlines and blessings of the gods.

Aeneas and the Origins of the Romans

Opposite the Lupercal panel in the Ara Pacis is a relief depicting Aeneas arriving at Latium. After the famous ingenuity of the Achaeans saw the Trojans lose their city, the poet Virgil has Aeneas (son of Venus) embark upon an odyssey directed step by step towards the mouth of the River Tiber and the fertile lands occupied by the Etruscans, Sabines and Latins. In the same way as Livy’s Ab urbe condita (published just a few years earlier) places Romulus and Remus squarely at the birth of the city, Virgil’s Aeneid adds the wanderings and travails of the hero of Troy to the edifice of Augustan authority as Aeneas makes his way towards ‘the destin’d town’ (as John Dryden put it), that others might advance, thereafter, towards ‘the long glories of majestic Rome’.1

Over the centuries, the arrival of Aeneas and the subsequent conquest of the cities of Latium became embedded in the story of Rome’s foundation. Augustan-era genealogies offer compelling credentials for Romulus and Remus deep in the Greek bedrock of Mediterranean mythology. Aeneas entered the royal line of Latium through marriage to Lavinia, daughter of the king Latinus, for whom the region is named, and who precedes the twins by fifteen generations. In recounting the foundations of a city that would come to rule the world, Rome’s first-century BC historians made its origins resonate with the project of empire and with its (likewise destin’d) renovation under Augustus – purchased with the riches it held to be rightly Roman.

Aeneas’ wanderings at Virgil’s behest puts deep history in play with the recent past. Destiny may have secured the marriage between Aeneas and Lavinia (who had, before his arrival, been betrothed to Turnus of the Rutuli), but it severed his earlier marriage to the Phoenician queen Dido of Carthage, whom he abandoned to continue his quest. (The chronology does not add up, but in matters such as these the reader needs to be tolerant.) Betrothal and dissolution both resulted in war: in Latium, leading to victory for Aeneas and the rise of his line; and, many centuries later, in the Punic Wars of the third and second centuries BC, where the sustained clash of the Roman Republic with Carthage (waged concurrently with the Macedonian Wars to the east) largely completed Rome’s ascendancy over the Mediterranean basin, securing its first colonies beyond Italy and, with them, the real prospect of an empire.

In the first instance, and through the intercession of Latinus, the Trojan refugees were peaceable in their settlement of Latium. Aeneas, though, saw it as the rightful inheritance of his dispossessed people, conducting a sustained and bloody warfare to place the people of Latium under his dominion. Eventually achieving a regional peace, he founded his own city of Lavinium (named for his wife, on the site of the coastal town of Pratica di Mare), which became the principal city of the Latin League. (By the time of Romulus and Remus, that position was held by Alba Longa.) Over time, Aeneas was adopted as the original Roman hero, embodying those qualities celebrated by Rome’s governing class in the era of its republic, and eventually by the emperor above all. According to Livy, Venus asked Jupiter (others have her ask the river god Numicus) to make her son immortal, which he did, in the form of the minor deity Jupiter Indiges. After an encounter between the Trojans and the local Rutuli at the Numicus river, his body was never found, which may have been immortalization at work or the consequence of a simple accident. The exploits of Aeneas were nonetheless told and retold over the following centuries, and by at least the fourth century BC had been distilled into a story that, through the Lavinian line, with a mix of Trojan blood, and Latin royalty and divinity, made Aeneas the ancestor of Romulus and Remus and a giant, therefore, of Rome’s prehistory.

In the Ara Pacis, the Aeneas panel captures the moment when the Virgilian hero makes landfall at the mouth of the Tiber – a first step bridging one long journey and another. An ill-fated sacrificial sow stands with the two household gods who accompanied Aeneas from Troy: the Penates, to whom Aeneas offers a drink. To his left is a figure who might just be Ascanius Iulius, Aeneas’ son and figurehead of the Julian line that ultimately gave rise to Gaius Julius Caesar and his adopted son Gaius Octavius, or Augustus, whose likeness elsewhere on the Ara Pacis monument bears a striking similarity to that of Aeneas. In the Iliad, Homer called Aeneas the ‘king of man’. Augustus, too, would share this claim and accept its inevitability as a matter determined by the gods. We, though, tend to read the early histories of Rome as a more fragile affair. ‘It should never be forgotten,’ writes classicist T.P.Wiseman, ‘that our picture of the Romans is almost wholly conceived from the work of authors writing … at the time when Rome was an imperial power which had defined Rome as different from, and superior to, the peoples it had subjected.’2 Fragile or not, this picture invites our reflection on the power of a Roman past capable of being insistently present.

Foundations

It may be premature to speak of Rome’s earliest beginnings as urbanization, or of those beginnings as a city, but bound up in the events depicted on the two above-mentioned panels of the Ara Pacis is a play between facts and myth that can be grounded, to an extent, by spending more time on the slopes of the Palatine hill and, at its northern base, in the Forum Romanum – even if all that dates to this time is either lost or buried. The term ‘Roma quadrata’ describes the roughly square shape of Rome’s earliest form as what many think was once a defined and defended hillside settlement on the Palatine. As Rome grew, it absorbed through treaty or conquest other nearby settlements, including those on the Quirinal hill (a traditional site of Sabine settlements) and in Trastevere (an Etruscan town), which would each rightly claim alternative origin stories for Rome based on an arguably older occupation of parts of the contemporary city. As the intersection, though, of a city fabric and an idea, Rome as Rome begins on the Palatine.

In the first decades of this settlement, the present-day Forum was a marshy valley between this hill and what might have been the Velian hill (or Velial ridge) – a rise depicted in ancient accounts, but which has long since been levelled. Those who stand behind the idea of an original Roma quadrata call the wall that defined it either the Palatine or, after its supposed author, Romulean Wall. Tradition dates this wall and the consequent founding of Rome to 753 BC, but even in the eighth century the Palatine was no terra nullius. Throughout Central Italy, a region of great antiquity, there is considerable evidence of Bronze Age settlement, and on the Palatine itself the oldest structure appears to date to the ninth century BC: a large oval hut on the western slope of the hill (roughly oriented towards the Forum Boarium (main, 23), near to the purported site of the republican-era Temple of Victory (inset, 31), Temple of the Great Mother (Magna Mater) (inset, 29) and Temple of Victoria Virgo (inset, 30), all originally dating to around the end of the fourth century BC. There is more evidence of this structure– posts for wall supports, a general sense of its scale – than of the purportedly more enduring buildings that replaced it around the time of the twins’ victory over Amulius. A ‘fossa’ grave – typically a stone-lined trench – indicates that people lived and died on the Palatine at least as early as the first part of the eighth century BC. Indeed, archaeologists Anna De Santis and Gianfranco Mieli in 2008 reported the discovery of six tombs dating to the eleventh and tenth centuries BC on the site on the north-eastern edge of the Forum Romanum developed in the 40s BC as the Forum Julii or Forum of Caesar. On the two crests of the neighbouring Capitoline hill, the Arx (or Citadel: main, 16) and Capitolium (main, 17), are sites of worship from around the third quarter of the eighth century, likely originating with a temple in honour of the god Jupiter Feretrius that arguably dates to the time of Romulus. The area between these two crests was, according to tradition, a sanctuary for foreigners and called Asylum. It, too, was inhabited from the ninth century BC.

Early Romans, it seems, worked the land and worshipped according to its needs. On the Palatine, there was somewhere to live and somewhere to bury, and on the Capitoline, there was somewhere to make offerings. At the end of the sixth century BC, the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus (Jupiter Capitolinus: inset, 4) joined the Romulean temple of Jupiter Feretrius (inset, 2) on the Capitolium, and was consecrated, in fact, in the first year of the Republic, 509 BC, despite having been vowed by the first of the Tarquin kings after the defeat of the Sabines more than two centuries earlier. (The Palazzo dei Conservatori [inset, 3] and the Palazzo Caffarelli [inset, 5], flanking Michelangelo’s sixteenth-century Campidoglio [inset, 4], now overwrite its footprint.) The idea of Rome might not yet have been born before the eighth-century BC adventures of Romulus, but in the artefacts left behind by the people of this time, evidencing their need for shelter, sustenance, death and worship, the city has its most tangible foundations.

The position of archaic Rome among the cities of Latium was initially secured by battle. Romulus was held to have successfully waged war with the powerful nearby city of Veii, as did Servius two centuries later. As Rome was a settlement established on the basis of a victory by shepherds over the king of Alba Longa, its population was founded on a colony of single men of the land and the region’s disaffected and dispossessed. The violent abduction of the Sabine women was an early act of deceit that secured wives and children for the first generation of Rome’s menfolk, which in turn gave Rome a union of sorts between a new city filled with landless unmarried men and the Sabine people, who were established on the Quirinal hill as well as throughout modern-day Lazio, Umbria and Abruzzo (Sabinium). As the story goes, the new Romans invited their neighbours to a games event intended to impress and befriend, but at a pre-arranged moment the Romans ‘fell upon’ the daughters of their guests (as Pierre Grimal euphemistically puts it), and kept them as wives.3

Tradition has it that this abduction took place around 750 BC, soon after the city’s foundation and long before its clear ascendancy above the region’s established cities – some of which, like Veii, it would conquer, while absorbing others as it entered into the Latin League and the mutual protections assured to its thirty or so constituent cities. There is as much evidence of this abduction as there is of Romulus’ own fratricide, but it has served tradition well by ensuring that the population of Rome would survive beyond its purely masculine founding generation. History accords honour to the Sabine women and those women of other tribes stripped of their daughters that same day for selflessly acting to prevent retribution against those who were now their own husbands.

By the end of the eighth century, there is evidence of enough urban activity to support the image of a structured and organized society at the base of the Palatine and Capitoline hills. For hundreds of years, the Comitium (inset, 14) – a platform for public debate – was at the centre of Rome’s civic life. All aspects of that life took place on the adjacent Forum Romanum, which by the start of the sixth century BC was an established setting for worship, trade, rulership, litigation and recreation. Over the course of two centuries, the bases of Rome’s urban infrastructure – markets and temples, roads and defences – were for the main part in place. Its people had evolved a considered and popular mode of government corresponding to a complex and functional religious culture. Together they supported the significant change to which Rome was subject over the course of the sixth century: it started out that century as a city ruled by kings and ended it as a republic.

Archaic Rome

Historians call Rome of the two or three centuries preceding the Republic ‘archaic’ Rome, a term which spans from the city’s murky beginnings to the end of the sixth century and the reconfiguration, therefore, of the social and hierarchical structures under which it had found its feet and flourished. Archaic Rome was ruled by a succession of kings who were, with two important exceptions, elected to their thrones by a curiate assembly. This assembly was comprised of citizens and arranged according to family groups. Up to the reign of Servius Tullius (who ruled 578–535 BC), there were thirty curiae, comprised of ten representatives of each of the three familial tribes that tradition dates to the reign of Romulus: the Ramnenses, the Titienses and the Luceres (the origins of which are as opaque as much of the history of this era). Each of these curiae was led by a curio maximus, who was a mature patrician – one of the nobles descending from the century of men appointed as senators by Romulus. Citizens who were not members of this nobility were called plebeians. The fifth king increased the number of senators to 200, which was further increased to 300 by two of the founders and the first consuls of the Roman Republic, Lucius Junius Brutus and Publius Valerius Publicola. Senators had wide-ranging powers that varied over time, details of which vary, too, from historian to historian. The Senate may or may not have elected the king (who lived in the Regia: inset, 26), or (later) maintained control when a dictator was appointed to address emergencies of various kinds.4

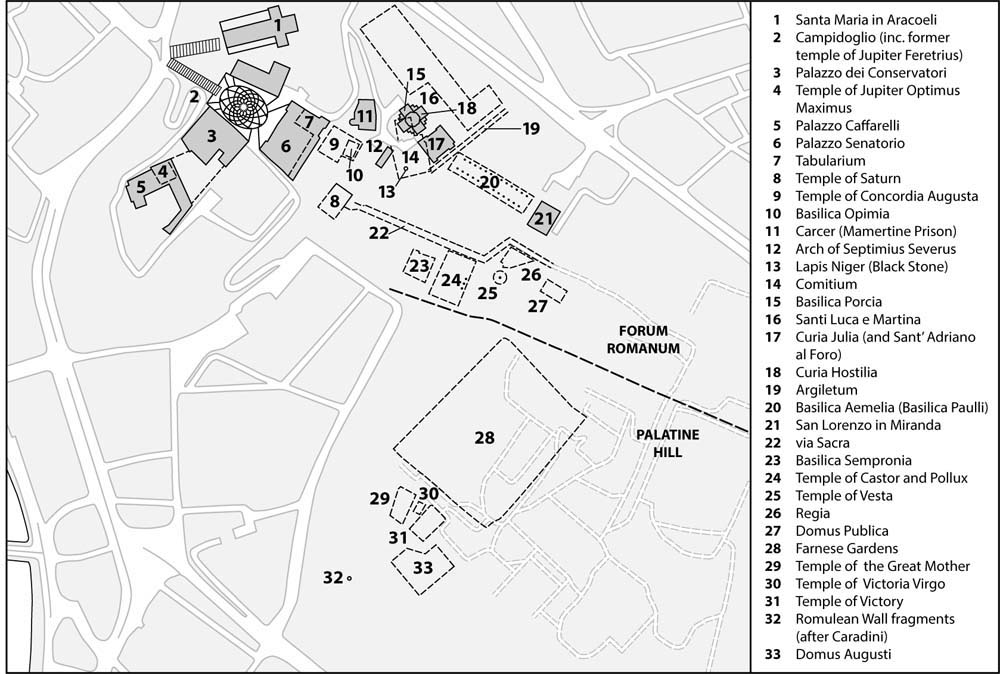

During both its regal and republican phases, the Senate (or Curia) met in the Curia (or Senate House). In archaic times, this meant the Curia Hostilia (named for the third Roman king, Tullus Hostilius: inset, 18), on the site of which the Church of Santi Luca e Martina (inset, 16) now sits. It was enlarged by the dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla in 80 BC (destroying the Comitium), then rebuilt by his son Faustus Cornelius Sulla after it was destroyed by riots in 52 BC, then converted into a temple by Julius Caesar during his dictatorship. The Curia Julia (inset, 17) in today’s Forum Romanum (figure 1.2) is a twentieth-century restoration of the building Caesar did not live to see finished, which was absorbed into the seventh-century Church of Sant’Adriano al Foro. (In The Roman Forum, David Watkin directs visitors to the doors of St John Lateran for an encounter with the original doors of the Julian Curia, which were moved there in the seventeenth century.)

Figure 1.2: The Curia Julia on the Roman Forum, with the dome of Santi Luca e Martina behind it, and the footprint of the Basilica Paulli-Aemelia and ruins of the Templum Pacis in the foreground.

Tradition accords seven men the title of King of Rome. Romulus (753–715 BC) was followed byNuma Pompilius (715/16–673/2 BC), who understood the importance of a well-ordered pantheon and is credited with organizing Rome religiously. Next comes the aforementioned Tullus Hostilius (673–642 BC), then Numa’s grandson, Ancus Marcius (642–617 BC). Three Tarquin kings follow: Lucius (616–579 BC), Servius Tullius (578–535 BC) and Lucius Tarquinius Superbus (534–510 BC) – all dates being tenuous to one extent or another. The ascendancy of the purportedly Etruscan Tarquins to the throne is an important indicator of the slow cultural assimilation into Rome of its religiously and artistically advanced neighbours. The son-in-law of his predecessor and son of a servant, the penultimate king, Servius, is portrayed by history as a popular ruler whose power, like that of Romulus, came from the people rather than the Senate (contrivances notwithstanding). Rome’s earliest defensive wall (on which, more below) honours him in name, recognizing his importance in defining Rome as a city for the Republic that would shortly follow. His Rome was cosmopolitan, even as it remained anchored in its identity to legend; it was a Rome defined as Rome in its own time, a matter of intentions and destiny over circumstance and evolution.

The tyranny of his successor, Tarquinius Superbus (Tarquin the Proud), ended the rule of kings. His reign began with the assassination of Servius and was cut short, in turn, by a popular uprising led by a coalition of four senators. It was born in violence and ended thusly. But this violence also gave birth to a growing awareness of what Rome had the potential to be, which was seized upon by patricians and plebeians alike. Toppling their monarchy, Romans took up a form of self-rule that was something between a democracy, an oligarchy led by the patrician class, and a theocracy. The Senate was led by jointly appointed consuls (originally called praetors), who were elected each year by the comitia centuriata (Centuriate Assembly) and whose appointment was in each case confirmed by the comitia curiata (Curiate Assembly). To all intents, the consuls had the power once held by the kings who preceded them, and were responsible for the protection and sound management of the Republic.

While much of the history of these first centuries was centred in and around the Forum, the force and momentum of Rome in its age of empire were such that very few buildings and structures of the regal and republican times survived that later epoch. The Lapis Niger (Black Stone: inset, 13) is an exception. Dating to the first century BC, it covers over what some believe to have been the grave of Romulus, but which seems more likely to have been a shrine to the fire god Vulcan, named the Vulcanal. Whatever the facts of the matter, these pasts are long buried and their cyphers largely closed to us – certainly to the casual visitor, and in some cases to the specialist. The Palatine contains a number of artefacts of archaic domestic life, but like everything else one might encounter there, these sites demand an archaeological imagination – often jollied along by twentieth-century reconstructions.

It is in and around the Forum – in the valley and on the surrounding hills – that we discover the greatest density of Rome’s monumental ancient history. The corollary of Augustus’ claim to have bequeathed a marble city is that the city of bricks he inherited was almost entirely overwritten, lending form and purpose to what followed in the imperial era, while leaving nothing but the faintest traces on the surface. It is typical of the problem that en route to the oldest traces of its human occupation one encounters a part of the Farnese Gardens (inset, 28) on the Palatine – only to find that this garden is no longer the product of a seventeenth-century antiquarian impulse but has been curated by twentieth-century hands to better represent the horticulture of antiquity.

To approach the history of Rome’s first centuries – to wander, that is, the Forum, the Palatine and the Capitoline as Rome’s archaic focus, or the Quirinale, Trastevere and, later, the Aventine as it expanded over time – is to walk a fine line between what we can glean from works of contemporary scholarship and reconstructions over many centuries and what we can learn from the historians of the late republican centuries and the years of empire – with their combination of chronicle, tradition and myth. In Early Rome and Latium, Christopher Smith reminds us that there is no ‘stratigraphy’ of myth – one cannot dig through it, like an archaeologist, in search of evidence.5 But a lack of evidence is not, in itself, basis for disproof. In the study and experience of a city soaked in legend, there is always a risk of not taking seriously something from the realms of tradition that might turn out to have substance. Recalling the discovery of what was possibly the Lupercal cave, a proposition advanced by archaeologist Andrea Carandini at the end of the 1980s serves to reinforce this point.

On the basis of his findings on the Palatine, Carandini argues the case for an original king and an original wall dating to the middle of the eighth century: an historical Romulus who demarcated and defined Rome as a city – an urbs, in spirit if not scale. The evidence may not support the traditional founding year of 753 BC, but Carandini insists that a founding gesture was made on the twenty-first day of one eighth-century April. This act was less defensive than spiritual, marking out the pomerium: a boundary that consecrated the proper and sanctified territory of the city. In the time of the Republic, a general lost his military authority by crossing the pomerium into the city; a divine portent lost its significance by crossing its threshold in departure; and tribunes (the five to ten plebeians appointed to represent pleb interests in the Senate) could only exercise their authority therein. Rome could (and would, eventually) hold sway over any land it could acquire (as ager publicus, or Roman land – more often than not held in private hands, and extending to provinces and colonies). It, however, required great ceremony to change the pomerium.

Carandini’s interpretation of this discovery invited controversy, being a question of ancient postholes (inset, 32) that supported a coincidence of fact and myth speaking ‘of something emerging from nothing’.6 Whatever might have happened, at whose hands and when, of that much we can be certain.

The Servian Wall

That which emerged was, before long, defined and defended by city walls. This Rome was no longer limited to the Roma quadrata that might once have described the first flowering of this city. This later, fourth-century BC wall contained a mature city – the largest on the Italian peninsula – that would soon come to exceed its own limits. Long replaced by the Aurelian Wall, which remains very much in evidence, the Servian Wall is largely destroyed, surviving merely as fragments along its ancient path. The earlier wall was long held in some quarters to be an extension of that built by Romulus, in which case the wall grew together with the city. By the end of the sixth century, according to Livy, Rome comprised of four tribal regions within the city – urbs et capitolium: the Suburana, Esquilina, Collina and Palatina, all named after topographical features, along with the Capitoline as Rome’s citadel and religious centre – and twenty-six regions beyond, making for a total of thirty tribal areas gathered under Rome’s banner. Livy relates how Rome’s defences were critically challenged in what some historians call the Battle of the Allia and others the Gallic Catastrophe in around 387 BC – a Senone invasion that saw Rome retreat to the Arx, emerging bruised, but intact. Tradition casts the construction of the Servian Wall, from 378 BC, as a response to this event.

We might well blame Fabius Pictor for the coincidence of this story (known largely thanks to his stylus and its influence on Livy) with the fourth-century BC firming up of details around the stories of Aeneas, Romulus and Remus – a long moment from which Rome emerged as a force underpinned by myth and chronicle. Building the Servian Wall meant that the Romans could stay in Rome rather than having to relocate elsewhere. Like Rome’s myths, the wall is a form of self-confirmation. Over the course of the next century, a suddenly land-hungry Republic would subjugate much of the Italian peninsula in the Samnite Wars. From this base, Rome would conduct war against Carthage and Greece in the third and second centuries BC. It may seem convenient to locate in this episode a moment of introspection and pre-emptive defence before Rome set about asserting itself throughout Italy and the Mediterranean. This, though, is what Livy, after Fabius, suggests, and they therefore imbue the wall with greater meaning for a reinvigorated Roman Republic.

Depending on your means of arrival into Rome, the remnants of the Servian Wall – the fourth-century BC wall, that is – could be one of the first things you see. Immediately outside Termini station, there are two sections of the agger (embankment) wall visible in the Piazza del Cinquecento ([main, 7], and another [main, 8] sits alongside the McDonald’s in the station’s underground shopping level). (Archaeologists have also located another small section underneath platform 24 [main, 9] – at which travellers from the airport at Fiumicino arrive on the Leonardo Express.) Heading south, there is a fragment in the Piazza Manfredo Fanti (main, 12), a couple of blocks from the station, in the gardens in front of the nineteenth-century aquarium (main, 13). Another piece can also be found underneath the small church of Santi Vito, Modesto e Crescenzia (main, 15, which dates to at least the ninth century), alongside the incongruously Neo-Gothic church of Sant’Alfonso de’ Liguori (main, 14, designed by Scotsman George Wiley in the 1850s); and yet another in the fabric of the Auditorium of Maecenas (on the Largo Leopardi [main, 21]) at the top of the Esquiline hill.

Some distance around the circuit, at the base of the Aventine hill and a quick walk from the Porta San Paolo ([main, 32], in the later Aurelian Wall), two sections sit alongside the via di Sant’Anselmo (main, 30), commencing in the Piazza Albania and including a section of the wall containing a defensive arch. An underground section on the Vico Jugario (main, 22: historically the Vicus Jugarius, leading into the Forum Romanum) once protected the base of the Capitoline hill; two courses of the tufo giallo (yellow stone) in which sections of it were built can be found on the roundabout on the Largo Magnanapoli, under the shadow of the medieval Torre Milizia, in whose grounds a number of other stones have been found, and below the raised gardens of the Villa Aldobrandini. In a neighbourhood dominated by ministry buildings (which, naturally, have been constructed on top of other traces of the wall), two decent-sized remnants flank the via Giosuè Carducci (main, 5) shortly after it meets the via Piedmonte.7

For both specialists and visitors, this is very much a matter of trying to imagine the whole from well-dispersed parts. The path of the Servian Wall may not be particularly interesting in itself, but it becomes so the moment we start to think of the extent of fourth-century BC Rome captured within its defences. At the dawn of the Republic, however, Rome turned its back on the Tiber and its western banks (thereby excluding the Vatican plane and hill and the fourteenth Augustan rione, or neighbourhood, of Trastevere and the Janiculum), going no further south than the Aventine.

At this time, Rome occupied the high ground, for which the river offered little by way of natural defensive support. That it was small enough to get around on foot can be confirmed even today, offering a study in contrasts with the sprawling metropolis of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Regardless of whether or not that first furrow was laid in the earth at the base of the Palatine in 753 BC, or whether the city’s defences expanded systematically to encompass the increased extent of regal and republican Rome, at some point in the first decades of the fourth century BC the city of Rome (and the idea of the city bound up in it) took shape within and by means of this wall. It offered a yardstick for what followed, and in this its legacy has long survived.

A City of Seven Hills

A tour of the path of the Servian Wall helps us to appreciate the distance Rome has travelled as a city. There is a remarkably rich history contained within it, matched, indeed exceeded, by what would come to take place beyond this first impression of the city. We now turn away from the very edges of the early republican city to its defining topography. This offers another way to regard the early republican city and a geography long occupied by the peoples who together realized Rome, and which shaped the city in the first centuries of its existence as such. It is exceedingly difficult, encountering Rome for the first time, to tease apart its layers, especially when monuments of great antiquity continue to shape the city over time.

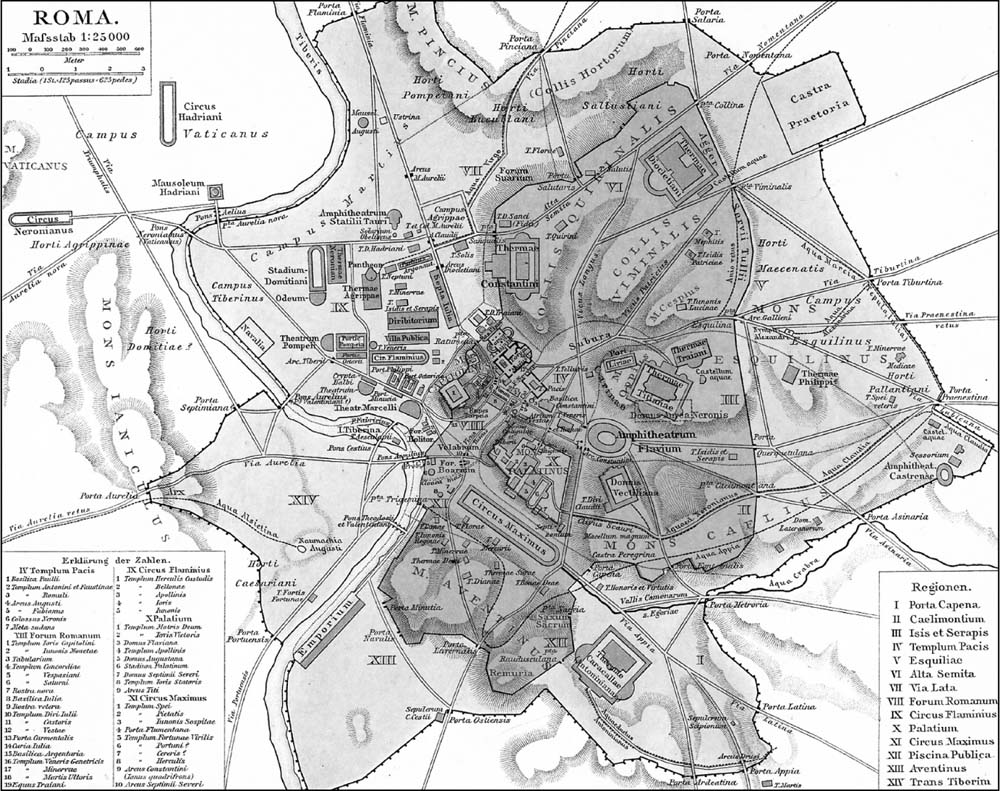

A map published by the German historian Gustav Droysen in 1886 describes something of the problem encountered by anyone confronted by the image of ‘Ancient Rome’ (figure 1.3). He superimposes the two key lifetimes of Roman antiquity – the republican Rome bound by the Servian Wall and the imperial Rome that quickly exceeded it – and flattens half-a-millennium’s worth of construction and erasure into one, practically homogeneous image of a developed but distant epoch in the city’s history. In this it is typical of maps of Roman antiquity, which reflects, in turn, the typical experience of one not versed in the detail of Rome’s archaeological remains. It is telling that the first-century AD Flavian Amphitheatre – the Colosseum – occupies, almost with natural authority, the centre of an ancient city defined by walls that never contained this structure. Very little of what was once bounded by the Servian Wall remains as a touchstone for an encounter with this historical epoch.

Figure 1.3: Gustav Droysen, Map of Rome, Allgemeiner Historischer Handatlas(1886).

Where architecture and infrastructure can fall as easily as they rise, topography tends to win out in the longevity stakes. One configuration of Rome’s seven hills is neatly gathered within the Servian Wall in Droysen’s image. He depicts the sparsely populated Aventine – covered as it was in lowly insulae (apartments, or tenements) rather than lofty domii (atrium houses) – and the Palatine packed with temples and aristocratic dwellings. Between them lies the mammoth ancient racing circuit of the Circus Maximus, dating to the sixth century BC and surviving as a vacated imprint on which one can still freely walk. Its long axis extends south–east to meet the start of the famed via Appia and north–west to encounter the Forum Boarium and the mouth of the Cloaca Maxima (main, 24), the city’s principal sewer, draining Rome’s flood-prone valleys of their excess water.

The Forum Boarium (main, 23) was a large cattle forum and predated the Emporium (main, 29), which was built in the second century BC, serving as the city’s main river port. Two temples still stand on the river-edge of this site (opposite Santa Maria in Cosmedin and its famous Bocca della Verità, Mouth of Truth): the Round Temple, perhaps one of several on this site dedicated to Hercules; and the Temple of Portinus, the god of the harbour. Around the edges of this forum the Capitoline, Palatine and Aventine hills rose up high above the Tiber to define Rome’s western edge. From south to north, the Caelian, Esquiline, Viminal and Quirinal hills form an arc that captures the city from the east. The Quirinal, northernmost of these, may have been absorbed into an expanding Rome as early as the sixth century through the integration of the Romans and Sabines.

Much is made of the famed hills of Rome, but to the extent that they remain part of today’s topography, they are far less pronounced than they were two millennia ago, with centuries of infilling, levelling and drainage robbing the city skyline of the drama they once offered. We can make a best guess at the original seven invoked – which differ from the montes that give name to the archaic celebration of the Septimontium – but this risks making a modern approximation of something that changed in composition as parts of the city changed level over time. Hazards of historical error notwithstanding, to move from one hill to the other is both relatively easy and rich with distractions, offering a direct experience of the scale of the city of Rome twenty-five centuries ago.

Given the antiquity of the traces of civilized life still to be found upon them, the Palatine is a clear contender for being one of the seven hills, as is the Capitoline, and we have already spent time on both. The peak of the Aventine can be reached today by following via Santa Sabina (main, 28), named for the fifth-century Dominican basilica, which terminates with the priory church of the Knights of Malta (main, 27). Extensive public gardens cover the shallow Caelian hill (Monte Celio), including those of the sixteenth-century Villa Mattei, now called the Villa Celimontana (main, 26); and the Basilica of Santi Giovanni e Paolo (main, 25), originally dating to the end of the fourth century AD. Further north, the slope extending north–east from the Colosseum through the archaeological site around the Neronian Domus Aurea (main, 19, now open after extensive restoration works) leads to the site of the Baths of Trajan (main, 20) on the mound of the Esquiline hill. Heading north, via Merulana leads to the fifth-century Papal Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore and, down via Cavour (main, 11), to Termini and (sitting before it) the Baths of Diocletian (main, 6). These baths occupy the juncture of two historical ridges now effectively separated by via Nazionale: the Viminal hill, staked out by the imposing Palazzo del Viminale (main, 10); and the Quirinal, now dominated by the palace and its extensive gardens (main, 4).

A tour of what is left of the Servian Wall might prove disappointing to the reader keen for a strong sense of what fell under Rome’s urban dominion at the moment of its republican coming of age. For one thing, beyond some street patterns that continue to respond to topography and the wall itself, even in its absence, there is very little to which you might attach your gaze. Even the visual spectacle of the hills has been dialled down over the centuries as various hollows have been filled by means of public works or built up as successive layers of construction recalibrated the city’s ground plane in its most heavily populated areas – flattening hilltops and filling in valleys. (One of the more iconic demonstrations of this is Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s eighteenth-century depiction of the half-buried Arch of Septimius Severus [inset 12] in the Forum Romanum – a matter not of subsidence, but of the city floor rising around it over time.) For another thing, as a modern metropolis and a major European capital, Rome now effortlessly exceeds its historical boundaries, so that the logic of its first circuit wall fails to impress upon us an image beyond that of a lost city intermingled with the footings of the modern world. It is, nonetheless, possible to stand unambiguously beyond the city of Rome, as it was then defined: cross the Tiber to Trastevere or the Vatican; descend the broad stairs of Michelangelo’s Campidoglio and head north or west into the plane of the Campo Marzio; climb the Pincean hill to visit the Villa Borghese or follow the via Veneto down to the Piazza Barberini. In the middle of the fourth century BC, none of this is yet Rome.

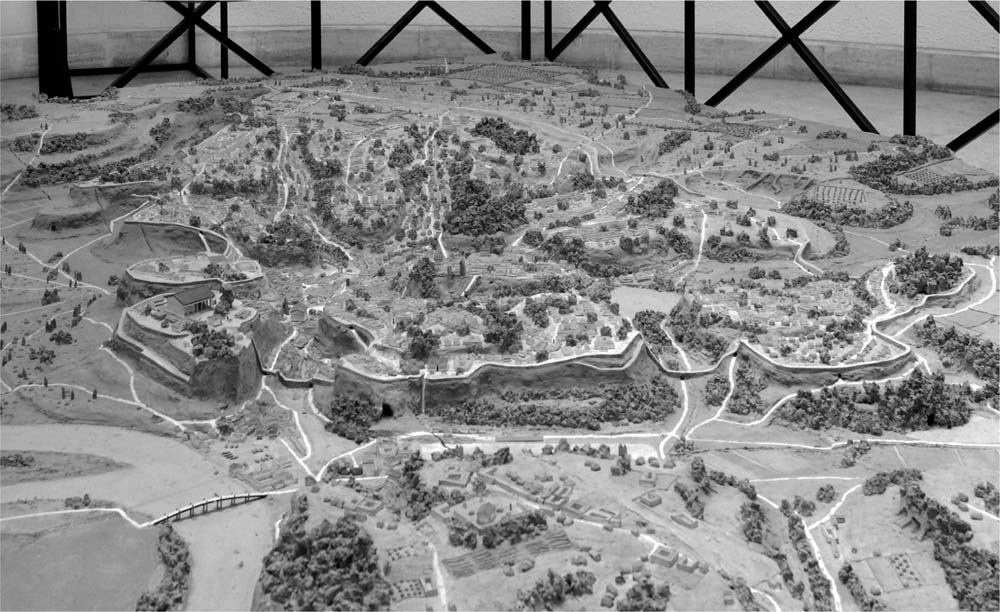

Well beyond the city’s republican borders (and a decent metro ride away from the historical centre) is the neighbourhood now called EUR, after the Esposizione Universale that was planned for 1942 (E42), although never staged. There, in the Museo della Civiltà Romana (Museum of Roman Civilization), is a model made in 1994 of the city at the end of the regal period that will have seemed quite recognizable to Romans born in the time of the Republic: rising dramatically above the plane of the flood-prone Campus Martius to show the urbs as a thing apart (figure 1.4). Its focus, though, its centre of sorts, is the valley between the Capitoline, the Palatine and the southern spur of the Quirinal. By moving to this spot from the city’s edges, we solve at least one of the problems noted above. Standing in the Forum Romanum, we are still unlikely to see anything that might have caught the eye of someone in the fourth century BC, or indeed the second century BC. However, in all senses, the Forum Romanum is – and was for a thousand years – the centre of this city, and to that centre we now return.

The Forum Romanum

David Watkin’s book on The Roman Forum has no obvious rival in its understanding of both the lay of the Forum Romanum and the complexity of this site, and it serves as an excellent companion to any visitor there.8 The Forum is a scene that can, in a sense, be stratified. With the right tools and a properly calibrated imagination, the clock can be reset to see along the length of its thoroughfare the way it might have been at the start of the Republic, or at the time of Hannibal’s incursions into Italy, or the height of Rome’s imperial might, or into the medieval and modern epochs. Few of us, though, have either the tools or the imagination necessary to reconstruct those scenes as they were, and so the Forum can come off as simply a big pile of history. Which it is. While the various layers of the Forum can be (and have been) recovered through excavation and documentation, it has been a setting of perpetual change, responding both to the amassing of events and structures and to the way each successive present moment chooses to celebrate, curate or ignore the various pasts that have been gathered upon it.

Figure 1.4: Lorenzo Quilici, Model of Archaic Rome(1994), Museo della Civiltà Romana, Rome.

As we will see below, four temples were built in this public thoroughfare before the death of Julius Caesar, but like the fragments of the Temple of Castor and Pollux (inset, 24), with their distinctive and conspicuous set of three Corinthian columns, their fabric, where it endures at all, dates not to republican but to imperial times. The Forum changed markedly and without remorse over the course of its life, letting those buildings and institutions no longer needed by Rome slide into obscurity and disrepair. This presents for those specialists who have sought to represent the history of this site the problem of isolating one or other layer of its history. Successive generations of antiquarians and archaeologists have sought to strike a balance between a dispassionate knowledge of the remains of the past and an invocation of the world from which they originate, between fragments and the coherent image. In Rome, and in the Roman Forum, religion and worship underwent considerable and definitive change. The governing institutions that had once been centred there were moved elsewhere. The demands of various building programmes over several centuries denuded many of the Forum’s structures of their marble, gold and bronze – offering a tacit assessment of its symbolic importance for Rome as a whole. Indeed, the Forum as painted by Turner in 1839 was labelled the Campo Vaccino in tribute to the cows he saw there, grazing among its monuments. The Forum is not one thing, and is neither singular nor reducible in its significance.

Even so, above or below a shifting ground plane, the Forum retained something of the centuries’ worth of alterations, elaborations, reconstructions and reorientations tracking its importance as a site of trade and exchange and of debate and resolution, on so many levels. Any view we might have of the Forum Romanum from any vantage today is more likely than not a view that takes the era of empire as its datum – the years, that is, commencing with the plans of Julius Caesar to restore those monuments showing their age (realized, in many cases, by his successor) and to extend the territory of the original Forum into new sites better able to cope with the grand scale of trade and exchange that accrued to a Rome serving as capital of the world. Our eyes, too, might as easily rest upon structures built eighteen or twenty centuries ago as fall upon twentieth-century tributes to monuments known but lost to time.

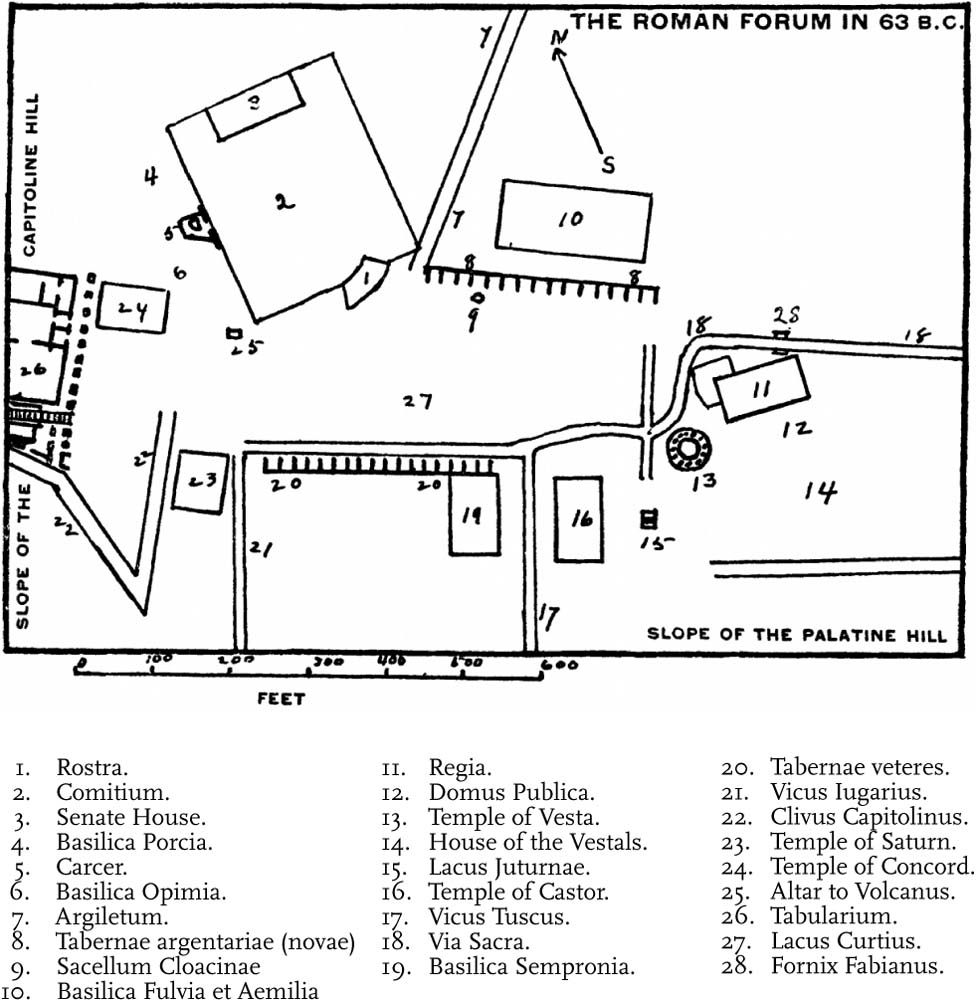

Figure 1.5: ‘The Forum as Cicero Saw It’, annotated plan by Walter Dennison, 1908.

If The Roman Forum helps with the overview, we can read a brief and century-old essay by the classicist Walter Dennison to imagine what the orator Cicero might have seen of the Forum in the year of his consulship, 63 BC (figure 1.5). This is the year in which Cicero exposed from the Rostra the intentions of one Lucius Sergius Catilina (or Catiline) to overthrow the Republic by inciting a popular uprising against the aristocratic Senate. This essay’s own relative antiquity means that it needs to be checked against more recent archaeological studies of the Forum’s contents (as documented in Claridge’s Oxford Archaeological Guide or the Touring Club guide Roma9), but questions of accuracy notwithstanding, it makes for a pleasant read even while taking a break from walking the Forum itself – sketching out an alternative, older Forum than the one we might be tempted to attribute to the Roman Republic on first impressions alone.

As we can quickly gather, the Forum was much developed in Cicero’s time from the earliest acts of draining the valley to establish the Comitium in archaic times. The oldest of its structures, dating to the rule of kings, are the Carcer (or Mamertine Prison inset, 11; Denn., 5, of which a trace remains on the edge of the Capitoline), the structures under the Lapis Niger, the Temple of Vesta (inset, 25; Denn., 13; visible today, in part, as a twentieth-century reconstruction) and the Regia (inset, 26; Denn., 11). The last of these was once the most significant building on the Forum. It originally housed the king, but during the Republic (and thus in 63 BC) it came to serve as the office of the pontifex maximus – the chief officer of Rome’s religions, which were in turn represented by the Collegium Pontificum. (This was a position to which Julius Caesar was elected in 63 BC.) The Temple of Vesta, with its associated housing for the Vestal Virgins, and, in front of it, now in outline, the Regia both sat alongside Rome’s oldest and most ceremonially significant street, via Sacra (inset, 22; Denn., 18).

Cicero addressed his fellow citizens from the Rostra, at the edge of the paved area of the Comitium and the Curia Hostilia. Cicero’s oratory would have reached his audience in a moment in which, as Dennison puts it, ‘Roman citizens still had a personal share in the business of state, and republican forms had not yet lost their meaning.’10 In this same part of the Forum, at the base of the Capitoline hill, the Temple of Concord was raised during the consulship of Lucius Opimius in 121 BC (since largely replaced by the first-century AD Temple of Concordia Augusta: inset, 9). (Lucius is notorious for ordering the execution of three thousand supporters of Gaius Sempronius Gracchus without trial following a mass conflict on the Aventine over Gaius’ defeated tilt that same year at the consulship.) A fire in 210 cleared the way for a series of new buildings that Cicero would have seen, including what was originally the Basilica Fulvia (179 BC) and later the Basilica Aemelia (or Basilica Paulli, dating to 55–34 BC: inset, 20; Denn., 10), which first served as a market hall, the outline of which is quite visible alongside the restored Curia.

This basilica occupied a site that had been used by butchers in the early years of the Republic and bankers from the fourth century BC onwards, and it was one of the first four basilicae of the Forum: Cato’s Basilica Porcia (inset, 15; Denn., 4) is the oldest of these, dating to 184 BC, and the Basilica Fulvia, first completed five years later, is in its final form the most intact, although Alaric’s Visigoth conquest of the city in AD 410 left little to boast over; the Basilica Sempronia (inset, 23; Denn., 19) was built by Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus in 169 BC and the Basilica Opimia (inset, 10; Denn., 6) in 121 BC. The Basilica Aemelia was separated from the Comitium by the Argiletum (inset, 19; Denn., 7), a street extending north to east from the Forum to Subura – a poorer district known for its vice (hence the themes of the 2015 film by Stefano Sollima that takes its name). Of the character of the Forum in that period, Dennison offers these thoughtful conjectures:

It is probable then that the Forum of 63 BC had a plain, perhaps antiquated, look and its structures showed but little influence of the elegant architectural forms of Greek models. Moreover, the buildings were comparatively few and not lofty, their small proportions being somewhat accentuated by the elevated situation of the temples and the newly erected Tabularium [records office: inset, 7; Denn., 26] on the Capitoline and the private residences of the Roman aristocracy [like that of Cicero himself] on the edge of the Palatine. Ruins of the Roman Forum of this period would impress us in much the same way perhaps as do the plain stucco-covered walls and columns of the forum at Pompeii today.11

It was not, then, the highly adorned, decorated and crowded precinct it became from the 40s (BC) onwards, after Julius Caesar returned from Gaul and his truncated dictatorship paved the way for Rome’s rule by an emperor rather than its senators. In its more modest form, the Forum allowed, however, for the Quirites (or Roman citizens) to gather and conduct business and politics of all sorts, to participate in games, to hear speeches and partake in debate, and to engage in civic and religious ceremonies. Along the northern and southern edges of the Forum were market stalls (the tabernae novae and tabernae veteres – new and old stalls – respectively). The area between the Temple of Concord and the Regia was relatively open.

Alongside the Regia was the home of the pontifex maximus, the Domus Publica, which explains why his office later extended into the Regia. Alongside the Temple of Vesta was a basin capturing the spring where the sons of Leda appeared after the Battle of Lake Regillus and Rome’s victory over the Latin League in 496 or 499 BC: Castor, born to the Spartan king Tyndareus, and Pollux to Zeus; both, therefore, siblings of Helen of Troy and Clytemnestra. Their appearance auspiciously marked a victory in what would have otherwise been a very short-lived Republic. Beside it was a comparatively humble temple in their honour (originally dedicated in 484 BC), already rebuilt twice by Cicero’s day and later overbuilt by Tiberius after a fire late in the first century BC. In the face of ruination, the three remaining columns of this later, imperial temple to Castor and Pollux have been standing their ground since the fifteenth century. Spanning via Sacra at the site of the Regia (and, today, the baroque church of San Lorenzo in Miranda [inset 21], which incorporates part of the second-century Temple of Antonius and Faustina), an arch once marked the victory of the general, consul (and dictator) Quintus Fabius Maximus over the Allobroges in 121 BC.

Turning back towards the Capitoline hill would have afforded a view of the Temple of Saturn (inset, 8; Denn., 23) on the site of cult worship dating to the start of the fifth century BC. After Christianity was regularized and pagan worship criminalized at the end of the fourth century AD, the old and new ways were reconciled and the mid-December celebrations of Saturnalia made their way into those of Christmas. What we now see is a fourth-century act of aristocratic resistance: built in honour of Saturn at a time when Rome was turning Christian within a mere generation of the moment when worship of Saturn would be rendered illegal. The Treasury was kept in this temple, under the guard of the Senate, and this was the building breached by Julius Caesar upon his return to Rome. Continues Dennison:

Looking up toward the Capitoline Hill one saw the towering Temple of Juppiter [sic] Optimus Maximus on the left and on the arx, at the right, the upper portion of the Temple of Juno Moneta [somewhere under the eastern end, most likely, of Santa Maria in Aracoeli (inset, 1), whose steps run away from those leading to the Campidoglio]; the latter was hidden in part by the Tabularium, or archive hall, recently erected [in 78 BC, under Quintus Lutatius Catulus] on the slope of the Capitoline overlooking the Forum [its walls today embedded into those of the medieval Palazzo Senatorio (inset, 1)].12

From Settlement to City

Concluding his tour of the Forum Romanum (and thus ours), Dennison recalls that Cicero witnessed many changes after his consulship, both to the Forum and to the Republic. Demolition of the Basilica Sempronia and the two rows of tabernae made way for grander buildings; works were initiated to replace the Curia Hostilia with a new Curia Julia; and the foundations of the Forum Julii were laid, presaging the diminished importance of the Forum Romanum over the imperial forums as the centre of Roman life. The city nonetheless consolidated around this central part of the city as the setting of its most important commercial, legislative and religious activities.

Over time and with Rome’s greatly increased regional authority, its population grew, but its historical patterns tend to follow a straightforward logic: the houses of the powerful gravitated to trade and power, hence the large domus constructions that once grouped around the Forum and crept up the slope of the Palatine. The construction of these basilicae in the second century BC replaced a number of sizeable, single-level atrium houses (domus) owned by Rome’s more powerful families on the slopes of the Palatine and along the via Sacra and other roads leading to the centre of the city, and which had gravitated to the Forum as the place where crucial decisions affecting commerce, government, taxes and foreign relations were regularly taken. Proximity to the Forum, in this sense, was proximity to power. As the population grew, it occupied an expanding urban field, hence the Lex icilia allowing plebeian occupation of the Aventine and the concomitant spread of warrens of insulae (apartment dwellings) thereupon, and the growing importance, too, of the Campus Martius, especially for migrants.

This was a city of growing stature, and its fabric responded to the need to project a strong presence, commemorate military success, pay tribute to an increasing array of deities and accommodate a population that would, by the second century AD, reach a scale not to be seen again for nearly two thousand years. In the wake of the wars with Carthage and Greece, Polybius was impelled, in his second-century BC Histories, to exclaim: ‘For who is so worthless or indolent as not to wish to know by what means and under what system of polity the Romans in less than fifty-three years have succeeded in subjecting nearly the whole inhabited world to their sole government – a thing unique in history?’13 He purportedly dedicated forty volumes to this difficult problem, to which Tacitus, too, turned in his Annals of AD 109:

Rome at the beginning was ruled by kings. Freedom and the consulship were established by Lucius Brutus. Dictatorships were held for a temporary crisis. The power of the decemvirs did not last beyond two years, nor was the consular jurisdiction of the military tribunes of long duration. The despotisms of Cinna and Sulla were brief; the rule of Pompeius and of Crassus soon yielded before Caesar; the arms of Lepidus and Antonius before Augustus; who when the world was wearied by civil strife, subjected it to empire under the title of ‘Prince’.14

Tacitus’ summary of these first seven centuries in the history of Rome is rough and ready but functional enough, and from the valley of the Forum we now turn to its conclusion and to Rome’s life at the centre of an empire.