3

A Middle Age

Saxa Rubra – Christianity under Constantine – The Basilica – A Turning Point – The Roman Church in a Christian Empire – Competing for Authority – San Clemente – The Commune of Rome

Saxa Rubra

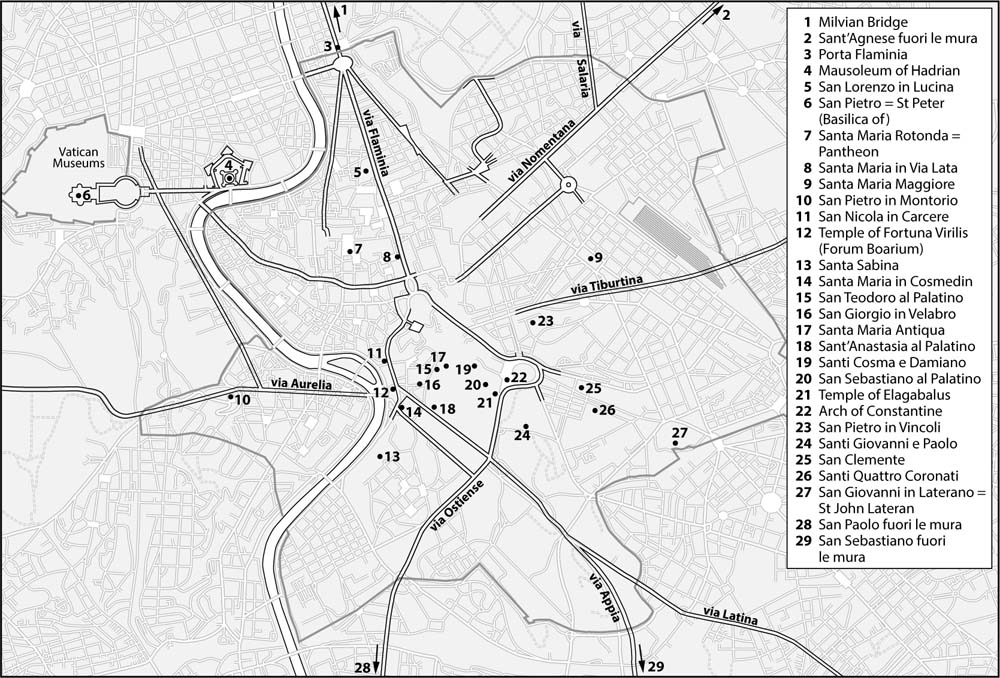

Since the third century BC, via Flaminia has been the principal route north from Rome, originally setting out from the Porta Fontinalis, at the base of the Capitoline, in the Servian Wall) and closely following the path of via del Corso – what was once via Lata. With a new wall came a new gate, and via Lata ran up to the Porta Flaminia (3, now the Porta del Popolo), skewing north and east to eventually reach Ariminum (Rimini) on the Adriatic coast. Today, as you go north from the Piazza del Popolo, you are taken through a well-established twentieth-century suburb and, in the blocks extending to its east, some of the venues and the athletes’ village built for the 1960 Olympic Games. This path brings you to the Tiber and to a bridge that bears the marks of more than two millennia of reinforcing, rebuilding and resurfacing to ensure safe passage or adequate defence, as needs over time have dictated. Despite the richness of the history it has witnessed, the Pons Milvius, or the Milvian Bridge (1), has long been associated with a battle staged not on the bridge per se but between this ancient landmark and the small village of Saxa Rubra a short distance further north – now swallowed up by the twentieth-century creep of the Roman periphery.

The form of rule established by Diocletian at the end of the third century was effectively a rule of four: two Augusti (principal emperors) and two Caesares (or Caesars, second-tier emperors), overseeing an empire that was split into east and west as a practical solution to the problem of ruling such a vast territory from a central capital. By and large, they ruled not from Rome, but from cities of strategic significance to the trading interests and defence of the Empire. Rome was a symbolically important city, but no longer active in the administration of the polity. From the foundation of the Tetrarchy in 293, the Augusti were Diocletian himself and Maximian, both of whom abdicated in 305, clearing the way for their respective Caesares to be elevated in the manner of heirs apparent, which they were. The death of the former Caesar Constantius in 306, and of his successor Severus (at the hands of Maxentius) the following year, provoked a power contest over the western branch of the Roman Empire. The system broke down as Constantine, the former Caesar of Gaul, Hispania and Britain and son of Constantinius, marched on Maxentius, the former Caesar of Rome. Both Constantine and Maxentius had been elevated to the highest rank with support from different quarters. Constantine won the contest for the title of Augustus of the Roman Occidens. His rule brought about the end of the so-called Second Tetrarchy and, after a little more than a further decade’s co-rule, the reinstatement of sole principality over a Roman Empire that would enjoy a brief spell of reunification – even as it witnessed the removal of imperial power from Rome as a city.

At the edge of the Forum, the enormous Basilica Nova documents the power shift that occurred at Saxa Rubra on the day, 28 October 312, when Constantine and Maxentius met in battle. Initiated by Maxentius, it was completed by the victor to an altered design. He furthermore installed a colossus in his own likeness after its completion. This is just one of the realignments to which Rome would be subject in Constantine’s ascendancy. The battle of Pons Milvia is legendary, not simply because of the consequences it wrought upon the history of the Roman Empire. To the side of the path taken by via Sacra, the Arch of Constantine (22) records the victory in relief, but a more compelling account awaits the traveller who finds his or her way across the city to join the incessant throng in the papal chambers painted by Raphael, now part of the Vatican Museum. There you can join the crowd taking in the fresco (figure 3.1) on which is captured the enduring symbolism of Constantine’s conquest, in a setting that owes everything to his victory: an early sixteenth-century rendition by Raphael and his gifted assistant Giulio Romano that celebrated the beginnings of the universal church – just as it had begun to fracture.

Figure 3.1: Raphael (with Giulio Romano), Battle of the Milvian Bridge, fresco, 1520–4. Hall of Constantine, Apostolic Palace.

Constantine’s newfound openness to Christianity was tempered by the greater responsibility of imperial rule. He retained the title Pontifex Maximus as a natural part of his imperium, even if he refused to enact some of the traditional religious functions of the office. His adoption of the sign of Christ was a response to what Eusebius Pamphili (in his Life) called a vision and what Lactantius (in his fourth-century Constantine’s Conversion) described as a direction in a dream. Maxentius himself had been warned (writes Latantius) that he would face defeat if he left Rome, but history favours the symbolism of a Roman emperor winning in battle under the Christian sign, at Saxa Rubra and thereafter. Over the two and a half centuries since Christians had started appearing in Rome, they had endured periods of intense hostility. Constantine’s vision and the success it heralded paved the way for newfound freedoms for Christians throughout the Empire just a decade after Diocletian’s Great Persecution. Constantine met his eastern counterpart, Licinius, in Mediolanum to discuss the status of Christians merely four months after defeating Maxentius, in February 313. Their agreement, the Edict of Milan, resulted in the legalization of Christianity, freedom to worship and compensation for a period of systematic oppression.

Constantine’s vision and the authority he drew from it paved the way for an entirely new religious basis for the rulership of the Roman Empire. The imperial court had already left Rome in the third century, and by the end of the fourth the emperor had outlawed the religions that the city had spread across the Empire – not Constantine, or not exactly, but certainly the sons and grandson who, at one point or another, succeeded him. The Curia was left in charge of a city of Romans that was, by the end of the fourth century, no longer able or willing to sustain the traditions and deities that had evolved in service of their city over nearly a millennium. That the worship of Pluto, Mithras, Venus and Jupiter would become illegal would have been unthinkable to Diocletian only a century earlier, but by the time it occurred the trajectory towards Roman Christianity was clearly enough defined.

Putting aside matters of belief, Giulio’s prolific depiction of the Latin cross in his Vatican fresco is an understandable anachronism for a sixteenth-century painter, and Constantine’s own labarum (military standard), depicted on various fourth-century coins and reliefs, sets the record straight. It is topped with the ‘chi-rho’ christogram formed from the first two letters of the Greek word for Christ – one of the oldest symbols adopted, along with the fish-shaped ‘ichthys’, by the Christian community. (The epigraphic museum at the Baths of Diocletian contains many early examples of its use in Rome.) The depiction of the winged Victory that heralds Constantine’s win on his triumphal arch is a nod to both established and new religions in a moment of transition. This figure is unambiguously transformed and multiplied by the sixteenth century into angelic soldiers fighting for Constantine’s cause. The result, however, holds: a vision that offers the promise of victory for Constantine and, through him, a faith that would become a universal institution.

Christianity under Constantine

There is understandably much to make of this turn from an ancient, pragmatically ‘pagan’ Rome towards the Rome of the middle ages and the Church, caught between temporal rule and spiritual power, but we would do well to think of it as not an abrupt change so much as a tipping point. Some decades ago, the Yale historian Ramsey MacMullen observed that Constantine himself made no direct reference to Christ (or indeed any statements indicating a strong grasp of Christian theology) before 321, the year in which he decreed Sunday the Christian day of rest. Constantine’s paths did not, he wrote, pass ‘instantaneously from paganism to Christianity but more subtly and insensibly from the blurred edges of one, not truly itself, to the edges of the other’.1

In Three Christian Capitals, Richard Krautheimer recalls the obstacles faced by an emperor giving public legitimacy to a religion that went directly against the devotional culture that had hitherto shaped Roman life and its institutions. The Senate, which governed the city, was a bastion of the Roman aristocracy, and it would have been unthinkable to its members not to involve the gods in all aspects of their lives – especially in securing the good fortunes of the city by enacting the rites through which the gods were paid their dues. Unlike Maxentius, who had been Caesar of Rome and Augustus of Italy, Constantine was hardly a familiar face to the Romans. He visited Rome on just three occasions, favouring the imperial cities of the Baltic and expansion to the Empire’s east. His gravitation towards Christianity compounded his apparent disinterest in Rome itself, causing offence among its ruling class, evidenced in his poorly received refusal on at least one occasion to make a ceremonial offering to Jupiter at his Capitoline temple as was called for by tradition. As any good ruler would, however, he rectified his missteps and enacted his role as the chief priest of the religions of Rome.2

Whether out of a sense of politics, tradition or devotion, Constantine demonstrated his adherence to the old religions in many ways that substantiate MacMullen’s characterization of his so-called conversion. It is a notable legacy of his reign that he built for the Christian Church, and built a lot. He donated imperial lands and funds from his private purse for a building programme within greater Rome. This ended the Christians’ reliance, to this point, upon the modest form of the domus ecclesiae –those domestic centres of worship adapted from private houses that had offered, in their anonymity, a degree of cover during periods of persecution and, in times of relative freedom, were intended neither to intrude upon nor offend the world around them. (The role of extra-mural catacombs is often recalled as a discrete setting for worship, for the celebration of the funereal feasts, or refrigeria, and an opportune place to hide, but these networks were neither anonymous nor exclusively used by Christians for burial.) Constantine sponsored the construction of new buildings dedicated to communal worship and the celebration of the Mass. Of the basilicae built in Rome during his reign, which are at least a dozen in number, some are opulent and others modest. Constantine’s relationship with the Senate may not always have been straightforward, but by careful consideration of where to build he neutralized any reservations it might have fostered over the newfound legitimacy given to Christianity by the Edict of Milan.

The Senate had no say over what the emperor could do on his own lands within the city, and so it could not object to the raising of San Giovanni Laterano (St John Lateran, 27) or, nearby, Santa Croce in Gerusalemme. It likewise had no say on what occurred beyond the pomerium, and basilicae were raised fuori le mura (beyond the walls) in honour of, among others, St Peter (San Pietro, on the Vatican), St Paul and St Sebastian (San Paolo, 28, on via Ostiense, and San Sebastiano, 29, on via Appia), St Agnes (Sant’Agnese, 2, on via Nomentana in the city’s north, alongside the family mausoleum dedicated to Santa Costanza) and St Lawrence (San Lorenzo, in the neighbourhood named for him).

You can get the sense of the remove of these sites from such centres of Roman life as the Forum or Campus Martius by walking from the Forum, past the Colosseum, to St John Lateran, which was founded by Constantine in the year of the Edict of Milan as the principal Roman basilica, its archbasilica and cathedral seat of the Bishop of Rome. (St Miltiades held that position until 314, but the great church builder St Sylvester thereafter commenced a reign that lasted until 335.) The Archbasilica of St John was built on lands confiscated from the Lateran family by Nero and which were part, therefore, of Constantine’s own estate. Fitting snugly within the Aurelian Wall, the basilica towered over its otherwise sparse surrounds, but since it was beyond the view of the Forum and two or three kilometres from the Campus Martius it was, to all intents, safely out of the way. The basilica we can visit today has seen its fair share of amplifications, reflecting its unaltered status as the city’s first church over more than 1,700 years. Those changes we face upon entering it were primarily conceived by Francesco Borromini in the middle of the seventeenth century, under the authority of Pope Innocent X of the Pamphili family – a restoration to its former sense of glory undermined by fire and damage during a period of fourteenth-century absence when the papacy temporarily relocated to Avignon. Even accounting for the tendency borne out in the history of church building to deprive simple structures of their modesty over time, or to enrich churches of increasingly clear traditional importance, St John Lateran knew gold from its beginnings: a personal statement of faith and support from the emperor himself, and a declaration as bold and direct as that made by the Colossus installed in his own basilica on the Forum. The Apostolic Palace (or Lateran Palace, not to be confused with the Apostolic Palace at the Vatican) was built in this same century and consecrated, like the basilica, by St Sylvester (I). It was for nearly a millennium a locus of Rome’s religious administration and observance.

The Basilica

We cannot easily accuse St Peter’s Basilica of being a study in modesty. Its dome dominates the Roman skyline, and its vast interior and richly adorned surfaces much less recall the decades in which Christianity emerged from a state of illegality and began to conduct itself with the protection of imperial law than they do the end game of those protections: the Church as an empire in itself. Taking the stairs down to the Vatican Grottos, however, offers a chance to make contact with the original basilica structure – its columns shorn off to make way for the vast reconstruction envisaged by Donato Bramante at the turn of the sixteenth century, but their bases sitting as a reminder of the original, fourth-century church it came to replace – Old St Peter’s – and hence of the first efforts to make way in Rome for a legitimized Christianity. The task of looking for tangible monuments from the fourth century is a little like looking for the architecture of republican Rome. In both cases, these early phases of what would come to be a great enterprise were overshadowed – sometimes early and suddenly, sometimes over centuries – by those expressions of the Church and the Empire at their greatest extent and at the height of their power. These beginnings take on, then, something of an abstract cast, but remain important nevertheless.

Constantine reigned uncontested as Augustus of the west from 313 onwards, and as Augustus of the whole Roman Empire from 324 to 337. In the space of a generation, Christianity went from being a persecuted sect to being a legalized form of worship alongside the pagan sects and cults, firmly on course to become the dominant religion of the Roman citizenry. The fourth century witnessed a long transition mirroring Constantine’s move from one set of blurred edges to the other, from a polytheistic worldview to one formed around the Christian faith and Judeo-Christian premises. The edges of Rome’s official Christianity, though, were moulded by traditions and habits shaped over many centuries. In making a departure of sorts from Roman antiquity into the millennium-long medieval epoch, the basilica was one of Rome’s first and most significant religious and cultural battlegrounds.

The legalization of Christianity and the restorative donation of land and riches by Constantine had placed the Church on a path that, by the end of the fourth century, saw it transformed into the only legitimate form of worship. Rome’s older religions were marginalized and then criminalized, and its gods began to fade into history. Rome entered the fourth century as the historical centre of a polytheistic empire – the largest the world had ever seen, even if its greatest extent was a thing of the past – and finished as a provincial city of increasingly symbolic value for a newly born Christian polity. It bore the very live traces of being the centre of what had become derogatively couched as a pagan world empire. The ruling families from which were drawn Rome’s governing class had deep roots with the city itself and, therefore, strong ties to the gods who had smiled on the city’s fortunes as it had subjugated the civilizations of the known world. Some could see the future in the entrails, as it were, and converted to Christianity; others rendered their devotion to the gods a private, indeed secret, matter.

As paganism was criminalized, all of those temples, all of those shrines, could no longer be used (openly, at least). Consider the Forum and via Sacra: its Temples of Saturn, of Roma and Venus, of Castor and Pollux; or the Temple of Jupiter, on the Capitoline. All neutralized. Since Christian worship needed to form a break from this religious past, it could not simply adapt Rome’s religious architecture for its own ends. The basilica was a new kind of building in a religious sense, even though the basilica as such was a common form of secular structure, in which magistrates applied law and settled disputes and in which a populace engaged in trade and exchange. Of course, in Rome nothing was done without the blessing of the gods, and so the basilica was neutral only ever to a certain degree. But it was nonetheless a site of invention, continuity and compromise, and ultimately it came to stand as an architectural symbol for the essential modesty of Roman Christianity in its earliest incarnations.

As settings for Christian worship, basilicae quickly came to abound in Rome. The care taken by Constantine to build with discretion was no longer necessary as members of the Curia either embraced the new religion or withdrew from public view. Basilicae were sometimes placed on sites of convenience, and at other times on sites of miracles, martyrdoms or burials. From the first century AD onwards, Christians had died in Rome either for what they did or for who they were. St Paul, for instance, a Jewish Roman from Tarsus (in modern-day Turkey) who sought his right to be heard by Nero, had proselytized to the Romans and was killed on the site traditionally thought to be occupied by the aforementioned basilica of San Paolo fuori le mura (28) – St Paul beyond the Walls, on the former Ostian Way. St Paul’s end is a matter of debate, although tradition dating back to the second century has him dying violently at Roman hands, perhaps beheaded. (The tomb long held to be his was excavated in 2009 and its remains were dated to the first or second century, consistent with this tradition.)

Over time, Christians came to venerate the burial places of the apostles and early martyrs, and St Peter’s tomb, in particular, became inundated with visitors. Some hold Peter’s death to have occurred during the bloody festivities of dies imperii in October AD 64, which marked a decade of Nero’s rule and, after the Great Fire in July of that year, the continued pursuit of Christians, whom he declared responsible. According to an errant tradition, Peter was crucified upside-down on a spot now occupied by a beautiful tempietto built by Bramante at the end of the fifteenth century – part of San Pietro in Montorio (10), on the Janiculum. Constantine founded a basilica (16) on the site where St Peter had been buried (the first basilica ad corpus, or ad corpo, built over a burial), which was close to Nero’s circus on the Vatican, where the official persecution of the sect resulted in its first Roman martyrs. An excavation in 1968 identified a first-century burial site believed to contain his remains, and the Baldachin of St Peter – the massive seventeenth-century canopy, designed by Gianlorenzo Bernini and supported by Solomonic columns – sits directly over that spot. From the outset, Constantine recognized the needs of this basilica, and among Rome’s earliest basilicae this was by far the most sizeable, reflecting its importance to the fourth-century Christian community.

Over the next thousand years, Rome witnessed the transition of the Church from the humblest beginnings to having an imperial reach all of its own. In the Jubilee Year of 1300, Pope Boniface VIII introduced the distinction between major and minor basilicae, with the major basilicae referring to the four principal churches within the Diocese of Rome: the fourth-century basilicae of St Peter, St Paul beyond the Walls (more commonly known as San Paolo fuori le mura), St John Lateran and, built in the 430s under Pope Sixtus III, Santa Maria Maggiore (9). The Basilica of San Lorenzo fuori le mura joins these four as one of the five papal basilicae in Rome. St Peter’s Basilica was significantly amplified in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and the Leonine City developed as the Vatican was cemented as the world headquarters of the Roman Catholic Church. The Basilica of San Paolo fuori le mura was almost entirely destroyed by fire in 1823, prompting one of the first and most complex discussions of the modern age around the matter of architectural heritage and restoration. As noted above, St John Lateran fell into disrepair during the Avignon papacy, requiring major building works, during which it was likewise enlarged and enriched. All of these papal basilicae now enjoy the baroque gloss of the recalibration of major sites of Christian worship in the Counter-Reformation, to which we will turn soon enough.

The buildings realized under Constantine’s authority were not consistent in organization, size or purpose. Some churches met the administrative and ceremonial needs of a religion that had long needed to simply make do. Some churches responded, as the Basilica of St Peter had done, to the need to venerate those who had been martyred for their faith. Others, like the Constantinian Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem or the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, served as shrines for key sites of the Christian faith. Some buildings were straightforward arrangements of atrium (outside), narthex (transitional), nave (interior), altar and apse, reflecting the Roman precedent. Others were, like Santa Costanza, centralized and circular buildings, which again drew from the vocabulary of temples like that of the Temple of Vesta in the Forum, or mausoleums like that of Augustus. The more important basilicae introduced a transept, which in its later exaggeration (in the cathedrals of the middle ages) made the plan look like a Latin cross. It was a building form governed not by strict legislation but by what were once the very simple needs of the Church and its communion and, for its builders, by opportunity and reinvention.

A Turning Point

St Paul was among the first to bring the Church to Rome. The circumstances under which St Peter died ensured that when it did flourish, it did so there. Constantine gave it credence and physical presence. After the reign of Constantine, though, Rome and its Church entered a period of marked uncertainty. From early in the fifth century, well-organized tribes from the north who had learned a thing or two from the Romans began making incursions into Italy, with Rome as a symbolic prize. The Visigoth king Alaric I put Rome to siege on three occasions between 408 and 410, each time resulting in significant gains and eventually securing access to the city and its treasures. Gaiseric the Vandal did some damage to the city when he entered with his troops in 455, and nearly a century later, in 546, the Gothic king Totila entered the city after weakening it by starvation for a year. In the meantime, in the imperial capital of Ravenna, the last of the Western Roman Emperors, Romulus Augustulus, abdicated to Odoacer in 476. Rome was no longer the centre of anywhere. It had been taken for the Gothic Kingdom and Ostrogoth Kingdom and remained a Gothic possession until the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian sought to reclaim the most important cities of the Western Roman Empire, like Ravenna and Rome, for Constantinople in the twodecades-long Gothic War (535–54), which left no clear winner. Rome was returned, ultimately, to Constantinople as a Byzantine island in a peninsula increasingly under the control of what would become the Germanic Kingdom of the Lombards.

Gregorius Anicius was little more than a boy when the Gothic War ended, but as Gregory I, styled Gregory the Great – later St Gregory – he would do much to ensure Rome’s eventual return to power through his systematization of the Church across Europe. In many respects, Gregory had an impact upon the medieval course of the Church as definitive as that of Paul in the first century. A Roman aristocrat by birth (of the Anicii family), former prefect of the city, a diplomat, skilled administrator and descendant of the fifth-century Pope Felix III (himself from a senatorial family), Gregory had entered a monastic life, but returned from it to take his place on St Peter’s throne. He became Bishop of Rome in 590, a little more than a century after the Western Roman Empire had fallen to Odoacer. The centuries between the pontificates of Sylvester and Gregory had seen papal authority much diminished. The Gothic War had severely depleted the wealth of the Eastern Roman Empire and left Rome as a mere vestige of its former self and little more than a regional city at some distance from the centre of European power.

As the hold of the Roman Empire had weakened into the fifth century, and with it, the regularity of central or coordinated rule, the spread of Christianity across Europe had acquired a cellular character. It had initially followed the path of the Roman Empire, remaining where it landed as the Empire itself began to shrink, and developing customs and characteristics that differed between, say, Northumbria and Sicily. By insisting upon a shared faith, common practices and administrative regularity, Gregory drew attention back to Rome as the impoverished but central seat of the Church, instigating arrangements that went far towards predicating the Roman Curia as a religious institution. In Rome, especially, he rallied his logistical acumen behind the task of feeding a city that had more or less been left by Constantinople to its own devices, and in so doing activated the economic conditions that would give the Church temporal power in the coming centuries as it acquired lands and bound the distribution of food to the provision of spiritual nourishment.

It would be an exaggeration to say that nothing worked at this time. There were baths; and aqueducts, albeit in private hands, still supplied water to the city. It would, however, be fair to say that those without means – including the large community of those who had sought refuge in Rome from the Lombards (or Longobards) – were not living in a state of great comfort.

The power of Rome to unite the Western Empire had diminished accordingly, so that the organization of the Church followed the lines of the various kingdoms and tribal alliances of which sixth-century Europe was comprised: Franks, Ostrogoths, Saxons, Visigoths, Britani, and so forth. In the face of all this, the Basilica of Santi Cosma e Damiano (19) on the Forum stands as a reminder not to paint with too broad a brush. Incorporating part of the fourth-century Temple of Romulus, as well as the offices of the city prefect, the building was donated by Theodoric and his daughter, Amalasuntha, in 527 and dedicated to the twin martyrs – Sts Cosmas and Damian – for whom it is named. The history of these decades is not (necessarily) a chronicle of conflicts between Christians and pagans. The Empire had been officially Christian since the fourth century and had promoted conversion among all those whose lands were conquered. As Rome’s borders receded, its exterior was populated by those who had set aside their own religious traditions in favour of the Roman Church (or instead, as in the Germanic uptake of Arianism, an amalgam of the old and the new), even as they no longer recognized Roman rule. Those who came to occupy the city of Rome were not necessarily pagans, then, even if their aggression towards Constantinople had them cast as such.

Celebrated for his practical sense, Gregory enacted a series of reforms that determined the place of Rome in the world across the following millennium. On the streets, he initiated a Church-led welfare programme and negotiated a rolling peace with the Lombards, who would otherwise pose a threat to the Church landholdings that quickly expanded throughout southern Italy, Sardinia and Sicily – and on which that programme relied. He built up the administrative structures of the Church to monitor spending and the flow of foodstuffs. Those charged with managing the practicalities of income and expenditure, importation and consumption, were accountable to a centralized organization.

Although they have all been overbuilt to varying degrees, a number of churches offer a material trace of this programme across several centuries: San Giorgio in Velabro (16); San Teodoro (15) at the base of the Palatine; Santa Maria in Cosmedin (14) on the Forum Boarium (made famous by the Bocca della Verità at its entrance); the fifth-century Santa Maria Antiqua in the Forum itself (17); and a short walk north, Santa Maria in via Lata (8, on the Corso) – all within a very short distance from one another, speaking to the concentration of people living in that neighbourhood, and the earliest, like San Teodoro and Santa Maria in via Lata, appropriating the older Roman stores on which the welfare centres, or diaconae, relied. The port area around the Forum Boarium was during these years a centre of importation and distribution, as it had been in centuries past. The sixth- and seventh-century reinvigoration of the city between the Forum and the Tiber also owes something to this process of adjusting for the needs of Christendom and a Christian Rome at its centre, reviving an area that had been all but abandoned as the public administration had atrophied and Rome’s temples were left empty.

In the realm of faith, Gregory aimed at popularization by embracing not the highbrow legacy of Rome’s classical age, which had in any case been thoroughly intermingled with Christian practices – the image of Rome, that is, and all it could be made to stand for – but a ‘simple faith’, as Krautheimer has put it, involving ‘new forms of religiosity shot through with irrational and magical elements’.3 It might be for the priests of the old order to maintain and placate a pantheon of gods; magical trees and rocks may have been the domain of the pagan primitives of the north; but saints and relics could work miracles.

This kind of Christianity particularly appealed to those northern European peoples who had been caught up in the wave of conversions emanating from the Constantinian reforms of the fourth century but who, through Rome’s own subsequent impotence, had melded its premises with all manner of local institutions and customs. As Krautheimer notes, ‘[I]t was through [Gregory] that Rome became the missionary center of Western and Central Europe, the organizational pivot of the Western Church, the spiritual guide of the converted Germanic tribe, and thus both the capital of Western Christianity and an increasingly powerful influence in Western politics throughout the middle ages.’4 (The infamous proliferation of and trade in relics owes something to this. Gregory himself, reflecting Roman values, looked with disfavour on interference with the corpses and burial sites of the martyrs. Others, though, sought a direct connection with the Roman martyrs, or with the Roman practice of venerating martyrs who might have died closer to home.) The effects of these two achievements – restoring the centrality of the Church in Roman life, and Rome to the centre of the Church – ran deep into the foundations of Rome’s longevity beyond antiquity. On one hand, as a functioning (if struggling) city, Rome was managed with great economy. The inhabited city contracted to an area within the walls known as the abitato, and parts of the disabitato (the emptied lands within the Aurelian Wall) were turned over to agriculture, viticulture, ruins and small intra-mural villages. As the Church assumed control of increasingly large parts of the city, its good management of the food supply lent temporal power to a spiritual and social project.

Rome had enjoyed a period of building under the reign of Constantine – and during the papacy of Sylvester and his successors – and while the Empire protected the city, it had continued to support new buildings for the Church as well as to shore up damaged defence works, roads, bridges, and the like. Santa Maria Maggiore (9) was raised in the interval between the visit paid to Rome by Alaric and that of Gaiseric, and remains one of the few architectural documents of that moment, with its central nave and mosaics dating to the papal reign of Sixtus III in the 430s. There were many, many empty temples that might have absorbed the needs of the Church as places of worship and the administration of social services, but it was generally disinclined towards converting pagan structures for its needs. That said, a law passed in 459 allowed for the recycling of building materials from disused temples and public buildings that had fallen into such a state of disrepair that they were arguably irredeemable. We now call this process spoliation, although what ‘disrepair’ and ‘irredeemable’ might mean in any given situation appears to have been an open question. The Basilica of St Peter benefited from this provision, as did St John Lateran, and almost any ‘new’ building project in Rome from the sixth century onwards. The restoration initiated in 461 by Pope Hilarius I of the fourth-century Basilica of Sant’Anastasia (18) at the base of the Palatine may have been an early beneficiary of this legal provision. But the buildings and monuments of Rome’s ancient fabric would continue to be a source of construction materials until the last great ecclesiastical building boom of the seventeenth century. Put simply, the modern state of Rome’s ruins owes more to sustainable building than to invasions from the north.

The first pre-Christian temple to be used as a church may not have been a temple at all, at least not in the strictest sense. Pope Boniface IV was given permission by the (Byzantine) Emperor Phocas to dedicate the Pantheon to St Mary and the Martyrs in 609 as Santa Maria Rotonda (7). The Pantheon stood alone for more than two centuries before another temple was pressed into use for the Church: Fortuna Virilis (12) on the Forum Boarium, dedicated in 872 to St Mary of Egypt. Although they had been consecrated in their own way, the redundant public buildings of Rome’s imperial rule were less problematic as subjects of conversion. As the civic welfare programme expanded, demanding food stores and distribution centres, an increased number of these were converted for the needs of a sparsely populated city now concentrated on the banks of the Tiber either side of the island between Trastevere and the Capitoline hill.

The Roman Church in a Christian Empire

The new kind of temporal kingdom that Rome built under Gregory and his successors grew through the action of missionaries rather than armies. It was organized centrally through an administrative regularity that harked back to a kind of Roman pragmatism that had helped to run an empire. A distant outpost of the Eastern Roman Empire, Rome was made more stable as a city. As a site of pilgrimage, it grew an economic base. Visitors came from across Europe, which fed demand for churches, accommodation, food and stables – a situation that has not changed markedly from that time to this. The earliest tourist guides to Rome were in circulation by the middle of the seventh century, and visitors reflected the geography of the Roman Empire at its most expansive. With Rome as the centre of the Church in a practical as well as symbolic sense, visitors to the city provided it with a religious constituency through which it projected a temporal authority. The sculpture placed on top of the Mausoleum of Hadrian (4) in 1753 by Flemish artist Peter Anton von Verschaffelt captures this intersection of spiritual mandate and temporal power.

In a vision ascribed to Gregory on the event of his papal ascension in 590 (or, perhaps, to his successor Boniface, as some accounts allow), the Archangel Michael alights on the monumental Mausoleum, repealing through divine interference the aggressions of flood (589), plague and Goth (590). In being assigned the name Castel Sant’Angelo, this monument reflects a turning point for the Church in the sixth century and, with it, Rome’s fortunes. It stands on the banks of the Tiber overlooking the ancient Pons Aelius (Aelian Bridge, now the Ponte San’Angelo) as an imposing and powerful symbol of Rome and the Church as dual strongholds. The changes to both that Gregory put in train secured the ascendancy of the Church over a city that found no real authority in its antiquity and was beset from all sides.

Cutting forward to the dawn of the ninth century: Charles the Great (Charlemagne) was crowned Emperor of Rome by Pope Leo III on Christmas Day of the year 800. This event was a culmination of two centuries of adjustments and trades shaping Europe’s landscape, feeding wars, drawing and redrawing the borders of kingdoms and duchies, and, within it all, consolidating the identification between Rome, the Church and the structures it maintained. It is no exaggeration to say that these relationships, even (or especially) in their mobility, shaped the history of Europe for a thousand years. The Frankish kings had consolidated power over western and central Europe over many decades. Charlemagne’s father, Pepin the Short, had received his education at St Denis in Paris, and became King of Francia with the blessing of Pope Zachary. Pepin and Charlemagne expanded their temporal power with ecclesiastical authority, and by force, as they converted heathens to the Christian faith. Making Christians was the same as making subjects. Charlemagne inherited the crown of Francia from his father in 774, acquiring, too, the Kingdom of the Lombards, and with it much of the Italian peninsula. He maintained a special relationship with Rome, protecting its interests as his authority cast a shadow across it. Did the Church serve the holy ambitions of the Kingdom of the Franks? Or did its temporal power emanate from its religious authority, and hence Rome and the legacy of St Peter?

Pope Leo’s long-lived predecessor Adrian (I) recognized Rome’s position as a city under the authority of the Roman Empire in the east, as well as its continued exposure to the threat of the Lombard Kingdom, by which it was all but surrounded. A much closer ally against the Lombards than the court at Constantinople, the Franks were Christian and they offered Rome protection, eventually absorbing the Lombard crown and neutralizing the threat of further warfare. The immediacy of their presence eclipsed, though, the authority of Constantinople. Leo’s election on the day of Adrian’s death in 795 reflected a concern that Charlemagne might have intervened in the selection of a successor. As it happened, the Lombard king was generous to the new pope, offering land and riches, but Leo was unpopular and taken captive by a band of Romans in April 799, en route from the Lateran to San Lorenzo, who accused him of misconduct both ethical and moral. Escaping his captors, Leo sought the assistance of Charlemagne that he might return to his proper place in Rome. A period of more than a year followed in which the king considered whether he could determine a pope’s innocence or guilt. He took Leo back to Rome, where a council of the Church met and determined that Leo could proclaim his innocence of the charges. His innocence accepted, his accusers were expelled from the city, and Leo was reinstated as pontiff. This all happened over the course of three weeks.

Two days after all was resolved, Leo rewarded Charlemagne’s loyalty with an imperial crown – in the Basilica of St Peter, above the remains of Peter himself. This had a couple of effects on Rome’s status in the centuries to come. For one, it introduced a structural ambiguity that would pursue Rome and the Church across the medieval age: did Leo (like a servant) place on Charlemagne’s head a crown that was naturally his, or did Leo crown him, bestowing as pontiff the mantle of emperor upon Charlemagne? The Liber Pontificalis tells it one way, while the royal chronicles tell it the other.5 Furthermore, in assuming the title of Roman emperor (Imperator Augustus Romanum), Charlemagne was at once claiming the mantle more recently held by the deposed Byzantine emperor Constantine VI and calling an end to the power of Constantinople over Rome. It would be another five hundred years before the term Holy Roman Empire came to describe the entity that was given form at the hands (or through the agency) of Leo, but Charlemagne quickly accepted and exercised his imperium as the head of the Frankish Empire. The various positions either left to Rome as a matter of course or available for Rome to fight for very much shaped the events that occurred at this moment, when Empire, Church and city were brought together in a single, contestable gesture.

At the heart of matters, however, is the authority that was acquired by Rome and its later emperors in the early desecration of the Church. The Carolingian hymn Felix per omnes festum mundi cardines contains, in its seventh stanza, this proclamation:

O happy Rome, stained purple

with the precious blood of so many princes!

You excel all the beauty of the world,

not by your own glory, but by the merits

of the saints whose throats you cut with bloody swords.6

Rome may have had a claim to a past of such legendary stature that Charlemagne’s new imperium would be a fitting extension of his monarchy over the Frankish and Lombard domains. Its currency, however, rested not upon the deeds of Augustus and Hadrian, but on the martyrdom (or purported martyrdom) of the early Christians.

Some of the most holy sites in Christianity were in Rome, and when the relic trade failed to satisfy those who found their faith renewed through proximity to the saints and martyrs, there was still the option of undertaking a dangerous and arduous voyage to visit the city itself. From the sixth century onwards, Rome welcomed pilgrims and their purses. In this historical landscape, Sts Peter and Paul had long stood out above all others, but they kept a large and diverse company. The so-called Salzburg Itinerary, Notitia ecclesiarum Urbis Romae, systematically took pilgrims around 106 cemeteries, churches and other holy sites, inside and beyond the Aurelian Wall. Each of the major roads in and out of Rome passed by cemeteries, martyriums and basilicae ad corpus: via Aurelia, via Flaminia, via Salaria (old and new), via Ostiense, via Nomentana, via Tiburtina, via Latina and, of course, via Appia. And within the walls, sites of various kinds line the incursion of arterial roads into the medieval city centre, thus shaping the pattern of the abitato.

This guide was amplified over time, but its original core dated to the mid-seventh-century papacy of Honorius I – a pope later anathematized for his theology, but who did much to raise and restore basilicae above the graves of the Roman martyrs. The Constantinian Basilica of Sant’Agnese fuori le mura (2) was restored under his authority and with great opulence, something documented, not least, in the Byzantine depiction of Honorius standing alongside the saint, holding a model of the basilica itself.7 Many churches that had been built under Constantine or in the immediate wake of his reign and which had fallen into disrepair across the fifth and sixth centuries received, like Sant’Agnese, a new lease on life into the eighth and ninth centuries – an act reflecting Rome’s stronger position in the world, but also recognizing the close relationship between grandeur and status in the practice (and economy) of pilgrimage. This is reflected in the Einsiedeln Itinerary (figure 3.2), likely dating to before the middle of the ninth century. Leading visitors and Romans alike through cross-sections of the ancient and medieval city, it offered an experience of Rome’s holy sites in the broader and deeper setting of its ancient artefacts.8

Figure 3.2: Map of the Seven Pilgrim Churches of Rome by Giacomo Lauro and Antonio Tempestra, ca. 1600.

Gregory the Great had reinvented the administration of the Church, and in doing so had given Rome a new position within Italy and the tattered ruins of the Western Roman Empire as the wellspring of Christendom. The martyrs gave Rome symbolic importance and compelled its allies to offer it protection. Its position at the centre of a vast ecclesiastical system combined with the immediacy of objects of veneration fed a sustained programme of building ex novo, restoration and adaptation. And it defined a contesting set of principles that gave rise to a steady flow of conflicts and compromises between the Church, the major Roman families and the new Roman Empire of Western Europe: all of which understood Rome as properly theirs.

Competing for Authority

The equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius in the Campidoglio is a replica, its original sitting protected nearby in the Capitoline Museums. The original was moved to the Capitoline from its long-standing spot outside the Lateran Palace (alongside 27) by Michelangelo, architect of the Campidoglio, under the instructions of the Farnese pope Paul III. Although its survival through the middle ages is sometimes credited to a misidentification of the figure of Marcus Aurelius as Constantine, the statue has long been a magnet for expressions of dissent. (Think of Domenico’s speech in Tarkovsky’s 1983 film Nostalghia.) And for punishment.

In 964, Otto the Great, whom some name as the first of the Holy Roman Emperors, had sought to depose Pope John XII to answer a number of charges for conduct that history would seem to support as being full of irregularities, both canonical and moral. It is worth noting that the young pope, 25 or less at the time of his election, had crowned Otto two years earlier and founded as an archbishopric the imperial Saxon city of Magdeburg. Perhaps relevant, too, is that John was of the House of Tusculum, from whom the Colonna descend, and son of the Roman ruler Alberic, whose deathbed wish was to see him named pontiff. Alberic resented being ruled by those Rome had, as an Empire, itself once ruled. Otto deposed John soon after his coronation as emperor and installed an antipope of his choosing: Leo VIII. Although Leo was Roman, he did not have the support of the citizenry, who rejected Otto’s authority to intervene and demanded John’s return. John denounced Leo and Otto and anyone of authority who might call him to heel, since no earthly soul had authority over the pope. He died before Otto could call him fully to account. (There are some colourful speculations as to what exactly he was up to as he drew his last breath.) From Otto’s point of view, this restored Leo as the rightful pope. From the perspective of the Romans, it cleared the way for a new election, which placed Benedict V on the Throne of St Peter. Like Leo, Benedict was a Roman. Unlike Leo, he was not in the implied vassalage of the emperor, but Benedict’s papacy lasted merely a month and a day. Otto marched upon and besieged Rome; the Romans capitulated, and Leo was restored. His papacy ended as it was meant to just nine months later, at which point the whole thing kicked off once more – variations upon a theme.

On the death of Leo VIII, the Roman families sought the reinstatement of their own candidate, Benedict, who died before the matter could be resolved. John XIII (John of Narni) was a compromise: he was appointed by Otto, endorsed by Rome and a member of the aristocratic family of the Crescentii. But upon his appointment he set about to shore up imperial authority against that of the city fathers, who were having none of it, and who expelled him from Rome. Otto had appointed one Pietro (or Peter) as the city prefect, but Pietro sided with the disaffected Romans over his emperor. Otto came to set matters right, entering the city in 966, whereupon a dozen decarones (senior city officials) were hanged for the action – as was Pietro, for an unspecified period of time, by his hair, from the statue of Marcus Aurelius, before being flogged and paraded through the city seated backwards on an ass, then consigned to prison and finally exiled.

It neither starts nor ends there, but the imagery of Pietro, strung up by Otto at the Lateran Palace, is a telling document of the unclear position occupied by Rome in the world at this time. The Church held itself to be above the Crown, bestowing upon the emperor his imperium. The emperor held all in his domain to be his subjects, including the officers of Christendom, who lent so much structure to the Frankish Empire. Many Romans thought themselves above it all: the Church was Rome’s gift to the world; so too the Empire, which was a Roman Empire after all, not simply modelled on the empire founded by Augustus, but its inheritance. Like the living subject of an unauthorized biography, the reality of Rome agitated the image on which the Empire maintained its symbolic authority, just as the Church’s recent arrival in the city, relatively speaking, with the persons of St Peter and St Paul, was a sticking point among those who understood their positions in the Roman social structure to reach back to Diocletian and beyond.

From the days of Charlemagne, the new Roman emperors had resided, when they came to Rome at all, at either the Apostolic Palace at the Vatican or the Lateran Palace – two of the most significant sites of papal power across the middle ages. The German emperors did not have their own palace in Rome, which was as much a matter of practicality as it was an admission that Rome’s rhetorical importance to the Empire did not match its geo-political or institutional significance. After many years of relative inattention to Rome, Otto III reinvigorated an imperial enthusiasm for the city amidst adolescent ambitions to clothe it in gold and raise it up as the true centre of the Holy Roman Empire. It was a naïve goal reflecting his inexperience – he had received the German crown at the age of 3, but did not get to use it before he turned 16, and at the end of his regency he went straight for Rome to be crowned emperor in 996. He initiated work on an imperial palace, which was long held to have been on the Aventine, although scholars have recently come to favour the more obvious possibility that he had sought to build on the Palatine, specifically among the ruins of the Domus Augusti in proximity to the church now called San Sebastiano al Palatino (20). (This church was rebuilt among the Palatine vineyards of the Barberini family in the seventeenth century, alongside the ruined third-century Temple of Elagabalus – 21.)

As it happens, Otto’s ambitions were curtailed. Obliged to leave Rome to attend to another of his cities, he felt the sting of Roman rebellion and never returned. His short-lived reign was ended by illness in 1002 and Rome’s eleventh century evolved into something less like a return to imperial glory than a long negotiation of its own stake in the imperial project. Although the ninth century had given Rome a new currency in the European scheme of things, the fact that anything in these years was built at all seems a minor miracle. Families fought other families for and against the pope; the city was divided into competing strongholds, in which streets and bridges were impermeable to the enemies of those who barred access. Familial factions were with the emperor, against the pope, or with the pope, against the emperor, and the contest for authority over papal succession was subject to waves of violent destruction – all of which was exacerbated by the invasion of Rome by the forces of the Norman king Robert Guiscard in 1084. The campanile towers adorning many churches and civic structures at this time were not necessarily intended as watchtowers, but they were doubtless put to use as such. (The twelfth-century reconstruction of both Santa Maria in Trastevere and Santa Maria in Cosmedin are good extant instances of these towers.) Foreign forces were inevitably supported by one or other Roman faction fighting for the strategic upper hand on any number of bases. The authority of the Church and the promise of a truly Christian city had, for instance, lent an authority to some Roman families; others relied on the authority garnered from the immediacy of the evidence of Rome’s antiquity and the position it implied against the Church and either for or against the Empire. No one position was immutable, and the history of these centuries abounds with instances of partisan mobility among Rome’s established families.

The eleventh- and twelfth-century city was filled with those same monuments and markers that had brought the seventh-century pilgrims through its gates. It was filled, too, with the remnants of antiquity: all the monuments we can see today and all those others not yet vandalized to realize the building booms of the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.9 When the canon Benedict wrote his guide to the marvels of Rome (Mirabilia Urbis Romae) in the 1140s, his attention was drawn not to sites of Christian importance but to the ancient world of Rome at the centre of an empire. It was not a casual antiquarianism so much as a politically infused invocation of Rome’s best days and of the structures of governance that secured them for its citizens: a time of consuls and senators, able to put down those enemies who would breach its walls. It called on visitors to regard this grand past at a crucial moment: when the Church was in the ascendancy, and when the leading Roman families required a strong sense of Rome itself in order to grasp the reins of power within a city at the centre of the world. The 1140s would witness an effort to restore the city to its people through the foundation of the Commune of Rome, to which we will turn shortly.

San Clemente

Rome’s path through the thousand years of change initiated by Constantine’s victory over Maxentius is not straightforward; it is complicated by ceaseless negotiations over the true legacy of the Roman Empire and the true nature of its enduring authority over the institutions of the medieval present; it is marked by fundamental transitions in worldview, sweeping rearrangements of the city’s organization, constantly shifting political and military alliances, and, throughout it all, Rome’s position in Christendom. As a city, much of Rome was returned to nature (and the ruin) and agriculture – what in the sixteenth century would be called the disabitato, the uninhabited land within the Aurelian Wall. By the eighth century, its absolute nadir, there were perhaps only three or four people left in the city for every hundred who had lived there in the time of Augustus. And in those built-up areas that remained inhabited, history piled up further: medieval accretions added to monuments of antiquity; temples, warehouses and other buildings from an era safeguarded by Roman gods adapted to the needs of the Church; marble and granite stripped from one building to realize another; towers built, towers destroyed; homes built, homes destroyed; Romans fighting Lombards, Franks, Germans, Normans, Saracens and each other; kingdom versus kingdom on Rome’s behalf; the Church against the city; the Church against the Empire; the Church against itself; the city against the Empire. This rich history adds up to a ceaseless contest between competing images of Rome as a city in (and above) the world, competing bases for its authority and competing legacies, therefore drawing on the lines reaching out from the past and leading towards the future. Every one of these contests was played out through the fabric of the city.

Sitting in an outlying part of the abitato, the Basilica of San Clemente offers a stratified cross-section of this problem that speaks to the slow and steady emersion from antiquity towards the powerful position from which Rome ruled the Christian world in the thirteenth century. Located today on via Labicana between the Colosseum and the Lateran, the Basilica stands as a testament to the triumphant rise of the office of the papacy over that of all other institutions – a moment of clarity emerging from a morass of ambiguities and discordance spanning the ninth to the eleventh centuries. Pope Gregory VII is credited with forcing the issue of papal sovereignty in his conflicts with the Emperor Henry IV. Gregory excommunicated Henry on three occasions; Henry facilitated the removal of Gregory and the installation of an antipope, Clement III (Guibert of Ravenna), having taken Rome in 1083 (a third attempt to assert his control over the city). Gregory held the Castel Sant’Angelo and his allies the Corsi and Pierleoni family held the Capitoline and Tiber Island, respectively, for a time at least. (The tower standing guard over the Ponte Cestio is a document of the Pierleoni occupation of the Island, as is the incongruous house standing opposite San Nicola in Carcere (11) at the intersection of Vico Jugario and via del Teatro Marcello) Gregory sought the assistance of the Norman Robert Guiscard, whose ‘Sack’ of 1084 brought to a head, and in the pope’s favour, the conflict between Gregory and Henry.10 Guiscard’s soldiers were destructive even as he liberated Gregory, and Rome turned against them both. Gregory died in exile, but not before having defended a principle of papal supremacy – Rome as the seat of the Church over the Holy Roman Empire – that would find its most expansive fulfilment just over a century later with the pontificate of Innocent III.

Among the damage done by Guiscard was the destruction of the fourth-century Basilica of San Clemente (25), dedicated to the first-century Pope Clement I, an early successor to St Peter. The original church was erected in the upsurge of church building that followed Constantine’s religious reforms, as were the nearby Santi Giovanni e Paolo (24), San Lorenzo in Lucina (5) in the Campo Marzio, Santa Sabina (13) on the Aventine and San Pietro in Vincoli (23, with Michelangelo’s ‘horned’ depiction of Moses). San Clemente shares a common history for being restored in the Carolingian era. As Ranierius, the future Pope Paschal II had served as its cardinal priest at the time of its destruction by Norman soldiers, and witnessed them ravaging with fire the nearby monastery and church of Santi Quattro Coronati (26), likewise dating to either the fourth or fifth century. Paschal oversaw the reconstruction of both buildings – a scaled-down and reorganized version of Santi Quattro Coronati, still a veritable fortress; and a lavish new church for San Clemente, superimposed on its fourth-century foundations, although several metres above the datum of the original. The atriums (or atria) in each complex pay tribute to the Roman architecture of the fourth and fifth centuries, broadly speaking in the context of a wider appreciation of the model of ancient Rome as it had been celebrated in Benedict’s Mirabilia – and thus paying tribute to an earlier, formative moment in the history of the Church at a time when it was once more asserting its place in the world.

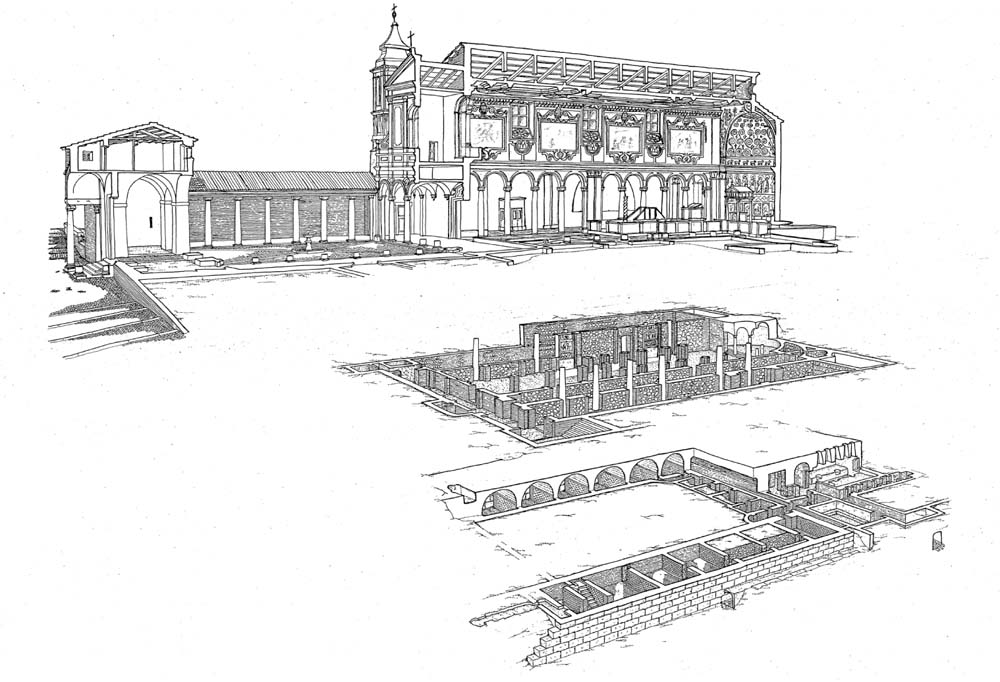

San Clemente (figure 3.3) builds upon Rome’s history symbolically, therefore, but also literally. Its twelfth-century reconstruction under Paschal sits almost directly upon the slightly larger footprint of the fourth-century basilica, which began life above ground but was below street level, or almost, by the twelfth century. Indeed, it proved necessary to the church builders of the twelfth century to slice off the top part of the walls to raise the new structure, and the supports of the upper basilica penetrate down through the older church – which was unused, and then unknown, from the time of reconstruction to the middle of the nineteenth century. Stairs now lead down to the narthex of the earlier structure, and further, in turn, to the structure on which the basilica itself was built. For under the church are the well-preserved and sprawling remains of a first-century AD (pre-Christian) house that had belonged to someone of means and stature, which included a warehouse and (later) a domestic altar to Mithras. The house had at some point in the first century functioned as a domus ecclesia, but not continuously, as the second-century Mithraeum bears out. It is possible that this, too, may all have been raised on the ashes of a house of republican-era origins that was destroyed by the Great Fire of AD 64. The ornate interior we can visit today is an eighteenth-century restoration of Paschal’s reconstruction, but the stunning mosaics remain a vivid record of its medieval worldview. Just as the frescos in the lower church recall that earlier chapter in the life of the basilica, lower still, the surviving Mithraeum reminds us of the world of compromises to which these transitions were inevitably subject.

Figure 3.3: Exploded perspective of San Clemente.

No cross-section in Rome compares with this for its legibility and significance. In San Clemente, we discover the Roman foundations of a structure that, in the twelfth century, invoked Rome’s authority over Christendom. Its authority was theological, of course, and fulfilled, in a way, with the Lateran Council of 1215, which proclaimed papal primacy and confirmed Frederick II as Holy Roman Emperor – the last thorn in the side of the papacy before the reign of his successor, Conrad of Swabia, concluded the Hohenstaufen dynasty and weakened, with its end, the authority of the Empire over Rome. While the thirteenth century confirmed Rome’s pre-eminence among cities, as caput mundi, chief city in a religious empire, it was undermined as the turn of the fourteenth century heralded a crisis of Rome’s identification with the Church and with it the basis for its position in the world of Christendom.

The Commune of Rome

The twelfth-century reconstruction of San Clemente and Santi Quattro Coronati could be misinterpreted as heralding a long-overdue peace. The balance of power in Rome – between the influential families, religious factions and the Empire – was fragile and repeatedly unsettled. Krautheimer recalls that Urban II, who was elected in 1088, spent more than half of his eleven-year pontificate effectively barred from Rome. Urban was no slouch: he launched the First Crusade, and adopted the Curia as a model of ecclesiastical management. However, he was French, and hence a foreigner, and regularly required the protections of the ‘fortified mansions’ of the Pierleoni – even his funerary procession (1099) was rerouted to accommodate the occupation of the Ponte Sant’Angelo by supporters of Clement III (Guibert of Ravenna). It was a city riven by factions and drawn in by temporary declarations of peace. The Concordat of Worms in 1122 would seem to have offered one such moment – Callixtus II and Henry V finding agreement over the problematic investiture of bishops, upon which hinged the question of papal authority within (and therefore over) the Holy Roman Empire. But the papal election held after the death of Honorius II in 1130 started a new series of conflicts: two elections held by two colleges refusing to regard the other as legitimate; and hence the investiture of two popes, Innocent II, the creature of the German King Lothair and the Frangipani family, and the Pierleoni Anacletus II (traditionally the antipope), who holed up in the Castel Sant’Angelo while simultaneously coordinating raids on the city’s churches.11

Amidst all of this, the declaration in 1143 of a Roman Republic, ruled for the people by a Senate, reinstated the ancient hallmark of Roman self-governance (and self-determination) bound up in the acronym SPQR. Asserting the primacy of Rome over both the Church and the Empire, the Senate was comprised of fifty-six citizens, both noble and less so, led by a patrician (patricius). This was, in the first instance, another Pierleoni, Jordanus, who, although a brother of Anacletus (who died in 1138), had not supported him. The pope, Innocent II, was invited in the clearest of terms to surrender his temporal wealth and power to the Roman Republic and to focus on matters spiritual, leaving the people of Rome to take care of all his earthly concerns. Demonstrating how easy it would be to serve the Church unburdened by riches, the city ransacked a number of the palazzi belonging to members of the cardinalate. By way of response, Pope Lucius II (elected into this situation in 1144) used a combination of guile and brute force to end what had from the time of his election rapidly evolved from a state of insurgency into the Commune of Rome. Of course, it was not only the Church that the Senate regarded as subordinate to its authority. After a decade of equivocating with Lucius and his successors, Eugene III and Anastasius IV, and with the king of the Romans, Conrad III, by the middle of the 1150s Rome faced both a new pope and a new emperor. The Senate offered to crown the king who deigned to rule in the name of Rome, Frederick I Barbarossa (Hohenstaufen). He declined the privilege in favour of a papal coronation (by the English pope Adrian IV, in 1155), which, as Krautheimer states so succinctly, ‘ended in the customary bloody battle with the Romans in the Borgo, and in the equally customary malaria epidemic, which forced a quick retreat on the part of the Germans’.12

The stand-off was resolved in 1188 through the intervention, ultimately, of Clement III, who within a year of his election to the papacy had figured out how to return temporal power to the pontiff and to restore the property that had been transferred from the Church to the city over the preceding half-century. A city administration emerged from the peace – a peace in which the Senate was subordinate to the pope, who chose its leader – and the ascendancy of the papacy secured authority not just over the city but also over the Empire.

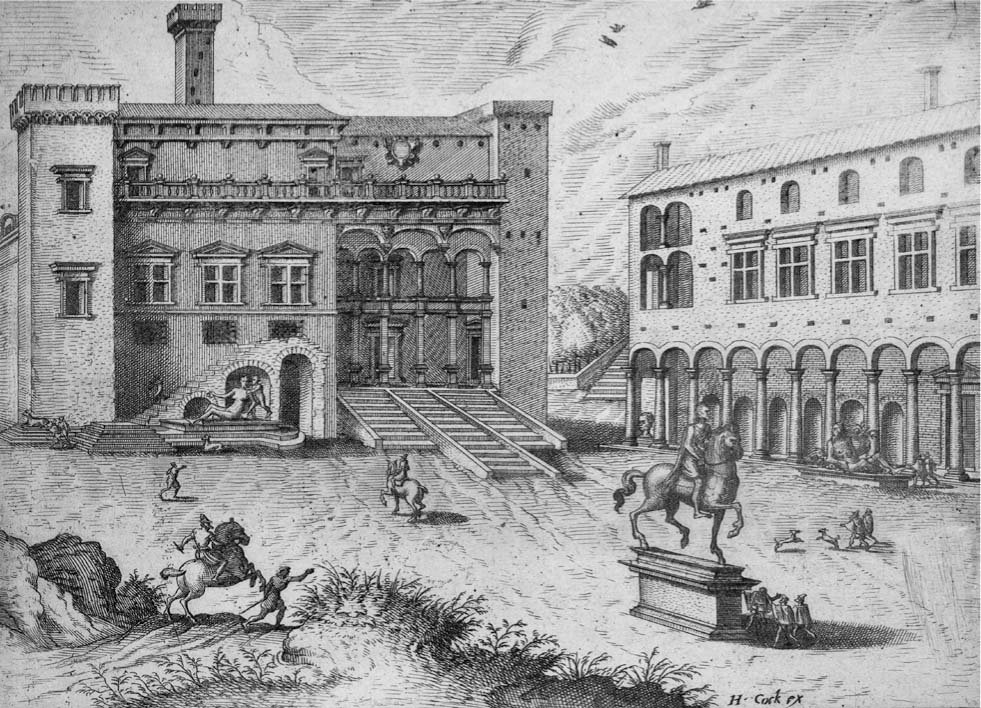

Today, the mayor and councillors of Rome meet in the Palazzo Senatorio (or Palazzo del Senatore) on the Capitoline hill (figure 3.4) – a building designed by Michelangelo in the sixteenth century to overwrite several other layers, structures both ancient and medieval, and completed by Giacomo della Porta in the first years of the seventeenth century. The tower was commissioned by Pope Nicholas V in the middle of the fifteenth century, and the square it faces stands as a compositional study in the anticipation of democratic process – all parts working together in harmony towards common ends (as James Ackerman suggested in his classic study on Michelangelo).13 The site has a rich early modern history of serving this goal. It was likely here that the Senate met during the decades of communal rule, from the 1150s through to the 1180s: a structure built upon the ancient ruins of the republican Tabularium, or official records office, parts of which remain visible from the Forum. Another structure had been raised in its place from around the end of the twelfth century, and a new Palazzo del Senatore was built across the second half of the thirteenth, its towers standing proud atop of the Capitoline, but in no less need of fortifications, despite the apparent security of its position. Rome’s situation, too, may have seemed deceptively inviolate. The rising importance and power of the French monarchy had come to exert a significant force upon the French papacy of Clement V, who in turn was a pawn in the highstakes tussle over European power. The Cathedra Petri was moved to Avignon in 1309, thereby marking a long period of absence on the part of the Church from Rome. The city was under the now distant control of a distinctly French papacy, but otherwise left to its own devices.

Figure 3.4: Lucas van Doetecum (after Hieronymus Cock), View of the Campidoglio on the Capitoline Hill, with Equestrian Statue at Lower Right [and Palazzo Senatorio at the rear], engraving, 1562.

The insurgency fomented in the decade spanning 1344 and 1354 by the popular leader Cola di Rienzo – self-proclaimed Tribune of Rome and would-be uniter of all Italy – speaks to the possibilities available to those Romans possessing an expansive imagination and an impatience with life on the margins. The episode is full of familiar moves: conflicts between powerful families; the Empire pitted against the Curia; the Curia against the Roman barons; and that oft-repeated belief in Rome as the sacrosanct wellspring of all power and authority. Cola did not have the force of history at his back, and he met his end, eventually, under ignominious circumstances, but his example reassures us that the departure of Clement V for the Kingdom of Arles in 1309 barely affected the continuity of Rome as Rome. And the return of the papacy and the Curia, nearly a century later, was a return, too, to the complex exchanges that had shaped Rome’s middle ages. In the fifteenth century, a fresh start would imbue such exchanges with a fresh hue. And it is to this episode that we now look.