Introduction: Thinking about Seeing

An Overview – A Work of Art of the Highest Order – Trajectories – From Analogy to Experience – Books on Rome

An Overview

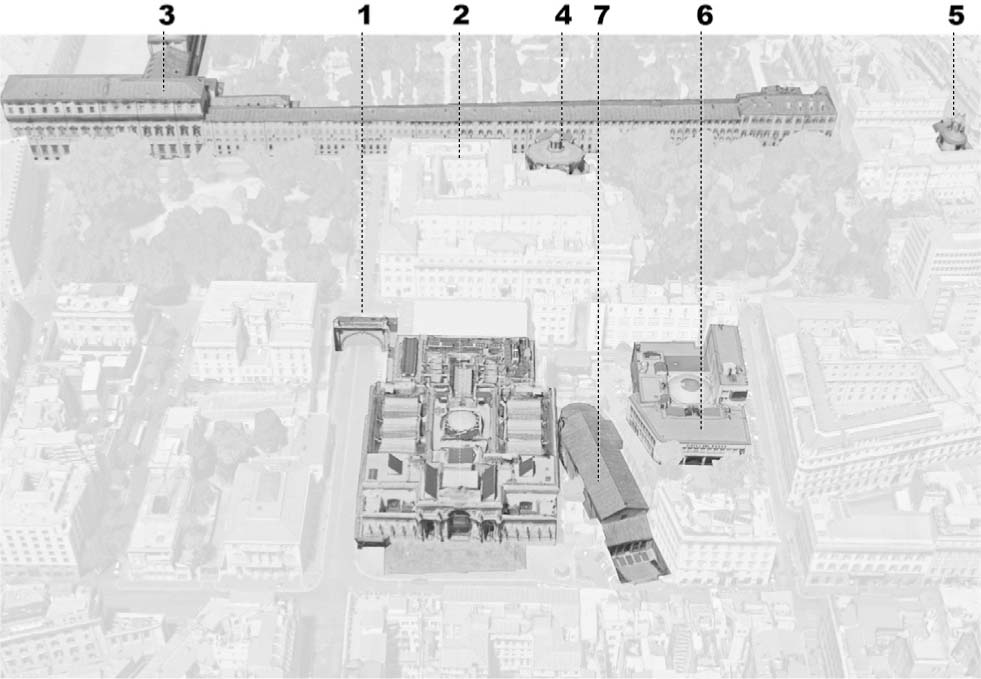

Where to start? Standing to one side of the walls of the Villa Medici in the gardens of the Villa Borghese, you can take in the sprawling ancient Campus Martius and beyond – the entire city, or so it might seem. You are above Rome, more so than if you had climbed the hundreds of steps that place you at the base of the lantern capping the dome of St Peter’s Basilica – and you get to keep that extraordinary monument in view. Looking across the arc from west to south, you can begin to pick out the forms that step forward into the vista: the dome of St Peter’s (figure 0.1, 1), above all, but also, to the right, the two churches dedicated to Santa Maria (2 & 3) that stand on the edge of the massive Piazza del Popolo; the surprisingly imposing dome of San Carlo on the Corso (4); and, further, the shallow curve of the Pantheon (5); just below, the incongruous Victorian spire of All Saints’ Anglican Church (6) on the via del Babuino; and off into the distance, a glimpse of the marzipan Monument to Vittore Emanuele II (Il Vittoriano, 7) – the Sardinian monarch who became first king of a modern united Italy. Beneath the line of hills that lies definitively beyond, and ringed by the highway system of Il raccordo, from this spot the city takes shape as a massive aggregation of marble, plaster and concrete. The monuments through which we identify Rome as Rome – St Peter’s, the Pantheon, the Vittoriano – do not stand apart from the city in time or space, but merely punctuate its sprawling urban fabric.

Figure 0.1: Rome from the Pincian hill.

A Work of Art of the Highest Order

This is one of several vantage points from which it is possible to appreciate parts of Rome as a single, complex entity, even if much lies beyond view, and even if the twentieth-century city bled well beyond the Aurelian Wall that now divides the city from its suburbs. At the end of the nineteenth century, before the sprawl took hold, the Berliner Georg Simmel penned one of the most profound modern meditations on Rome as an object of contemplation. He writes of the ‘indissoluble impression’ it leaves on the mind. As a collection of stuff amassed over centuries and centuries, in which innumerable cultures interacted with one another on innumerable terms, it should be an exercise in chaos. But Rome is indifferent to its past, just as its many and varied parts are indifferent to the whole to which they together give rise.

Here, many generations have produced and built next to and above one another, without any care for (and indeed without entirely comprehending) what came before, surrendering to the needs of the day and to the taste and mood of the times. Mere chance has decided which overall form would result from what has come earlier or later, from what is deteriorating and what is preserved, and from what fits well together or clashes discordantly.1

Making sense of Rome is not a matter of peeling back its layers. History piles up here, haphazardly. Its profound beauty, Simmel tells us, lies in the ‘wide and yet reconciled distance between the arbitrariness of the parts and the aesthetic sense of the whole’.2 The roped-off holes of archaeological excavation are commonplace, as are the sights of timeworn buildings wrapped in scaffolding (not yet given over to advertising); monuments are banal, and this failure of the ‘exception’ in Rome allows history to continue building upon itself, and despite itself, as it has always done. Simmel called it ‘a work of art of the highest order’, accumulating like the sediment that builds up flood after flood, emperor after emperor, pope after pope, endlessly recalibrating its ground-plane and its meaning to those who would look upon it. Its topography is a product, in part, of its antiquity; neighbouring buildings can sit on entirely different levels. ‘What makes the impression of Rome so incomparable’, he wrote, ‘is that in what separates one age from another, styles, personalities and lives which have left their traces here span further than anywhere else, and nevertheless merge into a unity, a mood, and a sense of belonging unlike anywhere else in the world.’ Yet whatever cohesion we find here results not from fine intentions: ‘the form in which Rome is built succeeds in transforming its fortuitousness, contrasts and lack of principles . . . into a manifestly tight unity.’ A unity reinforced (‘effectively, impressively and extensively’) by the time separating one element from the next.3 Rome obliges the present to live with the past, and by doing so to come to terms with it. It is not a city of frozen monuments. It is an experience of history.

It has been centuries since the Quirinal hill marked the north-eastern extremity of Rome proper, but one moment at the base of its southern incline illustrates Simmel’s observation. The long and busy path of the nineteenth-century via Nazionale casts an almost direct line from the Baths of Diocletian to Trajan’s Market and the Imperial Forums. Pausing about half-way along and looking up the slope towards the Quirinal Palace (or Quirinale), one sees several things at once. The via Milano runs perpendicular to the via Nazionale and disappears into the Traforo Umberto I (figure 0.2, 1) – the tunnel built at the outset of the twentieth century to modernize Rome’s traffic circulation, appearing in Vittorio De Sica’s 1948 film Ladri di biciclette (The Bicycle Thieves) as the protagonist Antonio pursues what he imagines to be his stolen wheels. Alongside it one can follow the stairs up the edge of the nineteenth-century Palazzo delle Esposizioni (2) towards the Quirinale (3). At the other end of the block one can do the same, ascending the hill along the via Genova, which brings you to the modest gardens that adjudicate between the two fine baroque churches that stand for the seventeenth-century artistic rivalry between Gianlorenzo Bernini (Sant’Andrea al Quirinale, 4) and Francesco Borromini (San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, 5). The street corner is marked by a nondescript multi-storey building of the kind that blends in easily with the others along the via Nazionale, in this case offering cover to a modernist fire station designed in the 1930s by Ignazio Guidi (6). But between the display windows of this building and the neoclassical mass of the Palazzo delle Esposizioni, an old church extends into the block, at odds with the angles of its neighbours or the street and dropping, too, down two metres or so to the fifth-century datum of the city. Extending sixty metres into this city block, the modestly gabled roof and arched entrance (narthex) of the fifth-century Basilica of San Vitale belie the extensive alterations to which this church has been subject over its life, reflecting, too, the history of Rome’s Christianization. Its presence recalls an earlier stage of the city’s history around which tourists obliviously shop, buses and fire engines speed, motorcyclists park, exhibitions come and go and life generally carries on. There is no real sense here that the weight of the past presses terribly much upon the shoulders of the present.

Figure 0.2: Prospect view north towards the Quirinale Palace.

Imagine Simmel coming to terms with this: a city scene being built up in the very decades around the moment in which he was writing. The history of modern cinema has acclimatized us to taking in the incongruity within any given frame of the very old coexisting with the very new in its depictions of Rome. But Simmel’s reflections will have come not from the city as represented but from the city as walked, following the paths that the first-time visitor would be remiss in failing to rehearse: a wander through the ancient forums, a hike up to the four fountains from Piazza Barberini, a stroll along the via Appia (Antica), past the monumental fragments of an imperial age and the catacombs marking the ascendancy of the next; the Colosseum, Trevi Fountain, Pantheon, Piazza Navona; St Peter’s, the Ponte Sant’Angelo, adorned with the angels of Bernini, and the imposing drum of Hadrian’s mausoleum, the Castel Sant’Angelo, on the Tiber’s western banks; the baths, the theatres, the circuses, the churches; and beyond the city, the gardens of the Villa d’Este or Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli.

These monuments populated the ‘postcards’ of tourists both grand and ordinary, and were already, in Simmel’s age, the things to see. Even if, today, you were to hire a scooter or hit the cobbles to check them off your list, you would have little change from a long weekend. Yet whether Simmel cast his eyes over Rome from the vantage of the lantern of St Peter’s, the steps of Trinità dei Monti, or nearby, like us, from the edge of the Villa Borghese, one can imagine him surveying this city in its dense entirety as he captured the ‘image that governs Rome: the immense unity . . . which is not torn apart by vast tension of its elements’.4

Trajectories

In forging a first impression of Rome, film is our friend, and if Simmel offers us a way to stand apart from the city and make sense of what we see, the camera has time and again shown us how we might move through it – drawing, as it were, individual paths to populate the impression with detail. One could reconstruct the frenetic route taken by Roberto Benigni’s taxi driver in Night on Earth (1991) or Nanni Moretti on his summertime dérives through Rome’s vacated suburbs in Caro diario (Dear Diary) (1993), or the character Jep Gambardella on his epic nocturnal tours in La grande bellezza (The Great Beauty) (2013). Few scenes, though, capture Simmel’s theme of a unity holding fast in spite of its tensions as well as the first minutes of Federico Fellini’s La dolce vita (1960). An American Bell 47 helicopter transports a statue of Christ across the city with a second helicopter in pursuit containing the reporter Marcello Rubini and his sidekick Paparazzo. The first shot tracks their arc across the face of the first-century Aqua Claudia, located in the present-day Parco degli Acquedotti – just beyond the Aurelian Wall in the city’s south-east. It is an incongruous sight: the modern technology of flight against the backdrop of this ancient piece of hydrological infrastructure, with the pragmatics of getting a parcel from one point to another confounded by the magic invoked by the Messiah sweeping through the air.

The chopper jumps to the suburb of Don Bosco, alongside the epic film studios of Cinecittà, and follows a small crowd running down the Viale dei Salesiani as the camera pans across the street front of what is now a well-established tree-lined avenue, but which at the end of the 1950s was part of Rome’s rapidly developing periphery, still very much a city edge under construction. Just before the shot follows the shadow of the lead Bell across a blank wall that is now long built out, a massive dome enters into view, Rome’s second largest after St Peter’s itself, belonging to the Basilica of San Giovanni Bosco and consecrated a mere nine months before Fellini’s film was released– a document of the modern city in its adolescence.

Like Fellini’s Messiah, La dolce vita arrived in the midst of Rome’s rapid post-war expansion, accommodating the needs of a ballooning middle class making the most of Italy’s ‘economic miracle’ and the arrival of thousands upon thousands of migrants from the country’s southern reaches moving towards the industrial north and to Rome as the Republic’s administrative centre. This moment is captured as the helicopters pass by a hillside housing precinct, an under-construction neo-realist invocation of the ‘traditional’ pre-industrial village life to which Italian identity remained bound. It is a testament to the difficulty of shrugging off the values that had shaped the generation that went to war in the summer of 1940, and to the widespread uptake of the public housing estates designed and constructed in the 1950s and ’60s. Its aspirations, however, lay alongside the young women we now see sunbathing on the rooftop of the modernist housing block typical of those that populated the wealthy new suburbs in the city’s freshly developed north – Parioli and its well-heeled neighbours. A fly-way of the newly installed innercity bypass system is visible to the left of the shot as the first helicopter passes on its way to St Peter’s, and as Rubini and Paparazzo pause to circle the sunbathers overhead, their gestured requests for phone numbers unsuccessful, before following their Saviour along the edge of the Tiber towards his final destination, the Piazza di San Pietro at the Vatican. The astute viewer quickly realizes that the Messiah makes nothing so neat as a simple arc across the Eternal City.

This diagonal path across the city’s topography, monuments and fabric gathers together several of the Romes these pages will invoke – a city that changes as forces within and beyond dictate; a city with edges challenged by the future taking shape beyond its limits and by its ever-shifting significance to the wider world. It is at once a centre and centreless. Simmel suggests that Rome can only be one thing by being many things at once. Another giant of modern thought suggests another way of seeing things. For Sigmund Freud, the experience of Rome was like an encounter with memory, its history a kind of burden sitting on the shoulders of the present.

Even before he first passed through its gates, Rome loomed large for Freud as an analogy for the workings of the mind. In The Interpretation of Dreams (1899) he records four occasions on which the city had come to him while he slept: a dream containing a view of the Tiber and the Ponte Sant’Angelo, in which he imagined himself departing from Rome in a train just as he realized that he ‘had not so much as set foot in the city’ but divined the view from an engraving; another in which Rome appeared ‘half-shrouded in mist’, viewed from such a distance that he was surprised by its clarity; a Rome in which the city’s ‘urban character’ had been given entirely over to wild nature, obliging him to ask a passing acquaintance for directions; and a fourth in which he reached an intersection only to be surprised by the number of placards in his native German.5 The interpretation of dreams is a job for professionals, but, read simplistically, these vignettes offer an insight into the experience of Rome itself: known only ever in part by its visitors, who must reconcile image with experience, beholden to a false sense of clarity and confronted by the impossibility of an authentic, unadulterated encounter with this city.

Three decades after writing The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud invited readers of Civilization and Its Discontents (1930) to consider the various forms taken by the city over the course of its history: the Palatine Roma quadrata, the city arranged around its seven ancient hills, the city enclosed by the Servian and then Aurelian walls, and so on. He wonders about the traces ‘of these early stages [that] can still be found by a modern visitor to Rome’. Some things remain in plain sight: beyond a few gaps, the Aurelian Wall was more intact in 1930 than it is today; fragments of the pre-republican circuit wall (or walls) have been recovered by archaeologists. The visitor with ‘the best historical and topographical knowledge’ can both ‘trace the whole course of this wall and enter the outlines of Roma quadrata in a modern city plan’. Yet where the city gives up its earlier forms, its contents have largely been either lost to time or decisively modified and modernized over the centuries. The modern visitor might have the means to locate the sites of specific temples, theatres and palaces, but their structures, suggests Freud, are largely the domain of the past rather than the present, ‘occupied by ruins – not of the original buildings, but of various buildings that replaced them after they burnt down or were destroyed’.6 Freud may have had in mind the large sheets of the Ichnographia Campus Martius, drawn by the Venetian architect Piranesi in the middle of the eighteenth century. Certainly, his observations could not resonate more with Piranesi’s capacity to invoke an ancient city by documenting what he could find, extrapolating part of the balance on the back of ruins and fragments, and filling in the rest with informed invention.

Freud asks his reader to imagine Rome as a city ‘in which nothing that ever took shape has passed away, and in which all phases of development exist beside the most recent’. Consider what we would see: ‘the imperial palaces and the Septizonium of Septimius Severus’ reaching their original full height on the Palatine hill; the statuary adorning the Castel Sant’Angelo in the medieval centuries in full view; the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, where stands the Palazzo Caffarelli on the Capitoline hill; Nero’s Domus Aurea along the site of the Colosseum; and the medieval church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva – housing among its artworks Michelangelo’s Christ the Redeemer and among its sarcophagi that of Renaissance painter Fra Angelico – all in view together with the ancient temple upon which it was built and for which it is named. We would return, too, to the Pantheon (figure 0.3). By standing alongside Bernini’s seventeenth-century sculpture of the elephant and obelisk on the Piazza della Minerva, one can regard the vast concrete drum of a structure originally raised during the reign of Augustus in the first century AD under the great imperial builder Marcus Agrippa – son of Lucius and thrice consul, the commanding frieze tells us (see pp. 95–103) – and reconstructed twice under the authority of Domitian and Hadrian in turn. Freud imagines a trick of the eye allowing the onlooker to see each phase in the life of these monuments at once. This, he says, is akin to the workings of the mental life.7

Figure 0.3: Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Elevation of the Pantheon and of other Buildings in Its Vicinity, engraving, Il Campo Marzio dell’Antica Roma (1762).

Freud found in Rome a demonstration of how memories press through into everyday life – and of how these memories can be weighty even as they shape an individual subconsciously. The analogy works just as well for a Rome reconciled to its past: a city steeped in its own history, in which contemporary life demands that one quite literally navigates around those holes in the ground in which the present is processing that which happened long ago. Rome’s antiquities break into the present persistently and without pattern. The relentlessness with which the present carries on around them regardless lent Freud an ideal analogy for explaining how we deal with memory. He helps us, too, understand something of how the past, here, is palpable in its presence.

An artwork by Elisabetta Benassi in the permanent collection of MAXXI (the National Museum of the 21st-Century Arts, in Flaminio) offers another take on this. Called Alfa Romeo GT Veloce 1975–2007, it consists of an empty car – make and model as advertised– sitting (when properly installed) in a darkened space. Borrowed light picks out the car’s general form, a latent menace, before the headlights spring into life, full beam, as a kind of shock. The car is the same model as that driven by the writer and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini on the night of his assassination, 2 November 1975, and Benassi confronts the spectator with this episode in Italy’s relatively recent cultural history as one not yet assimilated into an easy narrative – as something that once happened, but in a past beyond that which serves as the immediate backdrop to the present. Pasolini’s death is shrouded in secrets that run deep to the heart of Italy’s troubled anni di piombo – the Years of Lead, shockingly punctuated by the assassination of Aldo Moro in 1978 by the Brigate Rosse, or Red Brigades – in which elements of the radicalized left and right were in open conflict and in which the balance of power between governments at all levels, the Church, political groups and organized crime regularly gave way to acts of violence and disruption. Benassi’s centrepiece – the car – recalls all that one might prefer not to know in Rome’s more recent history.

We began with Simmel’s reflections on Rome, but Benassi brings to mind a line from another of his three portraits of Italian cities. Simmel writes of Venice (arguably Rome’s counterpoint) as ‘dreamlike’, a stage over which actors pass without in any way changing it. In a setting like this, ‘reality always startles us’.8 Rome, by contrast, is a city of realities that startle, shattering the illusion of ‘eternity’ and the narratives that it demands to reveal something that expands and contracts, rises and falls, impresses and disgusts. Even Simmel insisted that we can only ever take Rome in as a whole to sense its beauty as a thing entire. We cannot pause before too much in particular.

Books on Rome

To Simmel, Fellini, Benassi and Freud, we could add many other voices contemplating this city and that for which it stands, all trying to make sense of its complexities and contradictions. One more deserves note before we move on. In a recent reflection on ‘why ancient Rome matters to the modern world’,9 classical historian Mary Beard observed: ‘The truth is that Roman history offers very few direct lessons for us, and no simple list of dos and don’ts.’But the folly of ignoring this truth has been repeated across the centuries. The symbols and imagery of the ancient city – the city at the height of its reach (and decadence) – have regularly returned in moments where geo-political ambition and ideological security have reinforced one another. Beard writes of the temptation to view the contemporary plight of western society against the seemingly eternal measure that Rome offers. As much as Rome occupies the individual imagination, fed by paintings, comics, films, novels, etchings and history classes, it has also and often served as a yardstick for those imperial projects that found their measure in the empire founded by Augustus. The middle of the twentieth century witnessed such an invocation – the idea of Rome’s glorious imperial history and unassailable values underwriting Italy’s misguided imperial aspirations in the decades preceding the Second World War.

Against this backdrop, one writer made a gesture that should seem profound to anyone who reads and writes history. In October 1931, the 29-year-old poet and aviator Lauro de Bosis, an antifascist pamphleteer, took to the skies above the Italian capital to distribute two documents to its citizens. The first exhorted the King of Italy, then Vittorio Emanuele III, to act in a way that was worthy of his office and to curb the power of Mussolini and the spread of his fascist rule. The other was addressed to the citizens of Rome, extolling the virtues of a personal freedom that they had given up all too freely. De Bosis traded fuel load for paper and after a half-hour flight across Rome he drifted out to sea, where he is presumed to have crashed. An extraordinary episode on its own, it takes on greater meaning when read alongside the note he wrote in the early hours of the morning of his final flight and sent to his friend Francesco Luigi Ferrari to publish in the Belgian review Le Soir. In a powerful plea to his posthumous readers, de Bosis wrote: ‘Besides my letters, I am going to throw out several copies of a magnificent book by Bolton King: Fascismo in Italia. As one throws bread on a starving village one must throw history books on Rome.’10