THE WORM’S-EYE VIEW

Florence Nightingale, a legendary English Victorian figure, was a terror to the members of Parliament and the British army generals whom she confronted. There is a tendency to think of her simply as the founder of the nursing profession, a gentle, self-sacrificing giver of mercy, but the real Florence Nightingale was a woman with missions. She was also a self-educated statistician.

One of Nightingale’s missions was to force the British army to maintain field hospitals and supply nursing and medical care to soldiers in the field. To support her position, she plowed through piles of data from the army files. Then she appeared before a royal commission with a remarkable series of graphs. In them, she showed how most of the deaths in the British army during the Crimean War were due to illnesses contracted outside the field of battle, or that occurred long after action as a result of wounds suffered in battle but left unattended. She invented the pie chart as a means of displaying her message.

When she tired of fighting the obtuse, seemingly ignorant army generals, she would retreat to the village of Ivington, where she would always be welcomed by her friends, the Davids. When the young David couple had a daughter, they named her Florence Nightingale David. Some of Florence Nightingale’s feistiness and pioneering spirit seem to have transferred to her namesake. F. N. David (the name under which she published ten books and more than 100 papers in scientific journals) was born in 1909 and was five years old when World War I interrupted what would have been the normal course of her education. Because the family lived in a small country village, her first schooling consisted of private lessons with the local parson. The parson had some peculiar ideas of education for the young Florence Nightingale David. He noted that she had already learned some arithmetic, so he started her on algebra. He felt that she had already learned English, so he started her on Latin and Greek. At age ten, she transferred to formal schooling.

When it came time for Florence Nightingale David to go to college, her mother was appalled at her desire to attend University College, London. University College had been founded by Jeremy Bentham (whose mummified body sits in formal clothes in the cloisters of the college). The college was designed for “Turks, Infidels, and such as do not profess the Thirty-nine Articles.” Until its founding, only those who professed the Thirty-nine Articles of faith of the established Church of England were allowed to teach or study at the universities in England. Even when David was preparing for college, University College still had the reputation of being a hotbed of dissenters. “My mother was having fits by this time about my going to London … disgrace and iniquity and that sort of thing.” So she went to Bedford College for Women in London.

“I didn’t like it very much,” she said much later in a recorded conversation with Nan Laird of the Harvard School of Public Health. “But what I did like was I went to the theatre every night. If you were a student, you could go to the Old Vic for sixpence … .

I had a great time.” At school, she continued, “I did nothing but mathematics for three years, and I didn’t like that very much. I didn’t like the people and I suppose I was a rebel in those days. But I don’t look back on it fondly.”

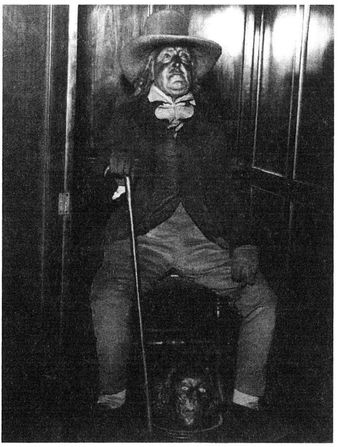

The mummified body of Jeremy Bentham, preserved in the cloisters of University College, London

What could she do with all that mathematics when she graduated? She wanted to become an actuary, but the actuarial firms would take only men. Someone suggested that she see a fellow named Karl Pearson at University College who, her informant had heard, had something to do with actuaries or something like that. She walked over to University College and “I crashed my way in to see Karl Pearson.” He took a liking to her and got her a scholarship to continue her studies as his research student.

Working for Karl Pearson, F. N. David was set to computing the solutions of complicated difficult multiple integrals, calculating the distribution of the correlation coefficient. This work produced her first book, Tables of the Correlation Coefficient, which was finally published in 1938. She did all these calculations, and much more during those years, on a hand-cranked mechanical calculator known as a Brunsviga. “I estimated that I turned that hand Brunsviga roughly 2 million times … . Before I learned to manipulate long knitting needles [to unjam the machine] … I was always jamming the damn thing. When you jammed it, you were supposed to go tell the professor and then he would tell you what he thought of you; it was really rather awful. Many was the time I had jammed the machine and had gone home without telling him.” Although she admired him and was to spend a great deal of time with him in his final years, David was terrified of Karl Pearson in the early 1930s.

She was also a daredevil and used to take a motorcycle on cross-country races.

I had a hell of a crash one day into a 16-foot wall, which had glass on the top, and I pitched over and hurt my knee. I was in my office one day and I was miserable and [William S.] Gosset came and he said, “Well, you better take up flyfishing,” because he was an ardent flyfisher. He invited me to his house. There was him [sic] and Mrs. Gosset and various children in the house in Henden. He taught me to throw a fly and he was very kind.

David was at University College, London, when Neyman and young Egon Pearson began looking at Fisher’s likelihood function, angering old Karl Pearson, who thought it all nonsense. Egon was afraid of angering his father further, so rather than submit this first work to his father’s journal, Biometrika, he and Neyman began a

new journal, Statistical Research Memoirs, which ran for two years (and in which F. N. David published several papers). Then Karl retired and Egon took over the editorship of Biometrika and ended the Memoirs. F. N. David was there when the “old man” (as he was called) was being usurped by his son and R. A. Fisher. She was there when young Jerzy Neyman was just starting his research in statistics. “I think the period between the 1920s and 1940 was really seminal in statistics,” she said. “And I saw all the protagonists from a worm’s-eye point of view.”

Jerzy Neyman with two of his “ladies,” Evelyn Fix (left) and F. N. David (right)

David called Karl Pearson a wonderful lecturer. “He lectured so well, you would sit there and let it all soak in.” He was also tolerant of interruptions from students, even if one of them spotted a mistake, which he would quickly correct. Fisher’s lectures, on the other hand, “were awful. I couldn’t understand anything. I wanted to ask him a question, but if I asked him a question, he wouldn’t answer it because I was a female.” So she’d sit next to one of the male students from America and push his arm, saying, “Ask him! Ask him!” “After Fisher’s lecture, I would go spend about three hours in the library trying to understand what he was up to.”

When Karl Pearson retired in 1933, F. N. David went with him as his only research assistant. As she wrote:

Karl Pearson was an extraordinary person. He was in his seventies and we would have worked all day on something and go out of the college at 6:00. On one occasion he was going home and I was going home and he said to me, “Oh, you just might have a look at the elliptic integral tonight. We shall want it tomorrow.” And I hadn’t the nerve to tell him that I was going off with a boyfriend to the Chelsea Arts Ball. So I went to the Arts ball and came home at four to five in the morning, had a bath, went to the University, and then had it ready when he came in at nine. One’s silly when one’s young.

A few months before Karl Pearson died, F. N. David came back to the biometrical laboratory and worked with Jerzy Neyman. Neyman was surprised she did not have her doctorate. At his urging, she took her last four published papers and submitted them as a dissertation. She was asked later if her status changed as a result of being granted a Ph.D. “No, no,” she said. “I was just out the twenty-pound entrance fee.”

Looking back at those days, she noted, “I’m inclined to think that I was brought in to keep Mr. Neyman quiet. But it was a tumultuous time because Fisher was upstairs raising hell and there was Neyman on one side and K. P. on the other and Gosset coming in every other week.” Her reminiscences of those years are much too modest. She was far more than a worm “brought in to keep Mr. Neyman quiet.” Her published papers (including one very important one cowritten by Neyman on a generalization of a seminal theorem by A. A. Markov, a Russian mathematician of the early twentieth century) advanced the practice and theory of statistics in many fields. I can pull books off my shelf from almost

every branch of statistical theory and find references to papers by F. N. David in all of them.

When war broke out in 1939, David worked at the Ministry of Home Security, trying to anticipate the effects of bombs that might be dropped on population centers like London. Estimates of the number of casualties, the effects of bombs on electricity, water, and sewage systems, and other potential problems were determined from statistical models she built. As a result, the British were prepared for the German blitz of London in 1940 and 1941 and were able to maintain essential services while saving lives.

Toward the end of the war, as she wrote:

I was flown over in one of the American bombers to Andrews Air Force Base. I came over to have a look at the first big digital computers that they built … . It was a Nissen hut [called a Quonset hut in the United States], about 100 yards long, and down the center were a whole lot of duckboards, on bits of wood you could run on. Either side, about every few feet, there were two winking monsters, and in the ceiling was [sic] nothing but fuses. Every thirty seconds or so, the GI would run down the duckboard with his face up to the sky and push in a fuse … . When I got back, I was telling somebody about it … and they said, “Well, you better sit down and learn the language.” And I said, “Not on your nelly. If I do, that’s all I will ever do for the rest of my life and no, I’m not going to—somebody else can!”

Egon Pearson was not the domineering person his father was, and he initiated a new policy that had the chairmanship of the

biometrics department rotate among the other members of the faculty. About the time F. N. David rotated to the chairmanship, she had begun working on Combinatorial Chance, a book that is one of the classics in the literature. It is a remarkably clear exposition of complicated methods of counting, known as “combinatorics.” When she was asked about this book, in which exceedingly complicated ideas are presented with a single underlying approach that makes them much easier to understand, she replied:

All my life, I have had this beastly business that I start something and then I get bored with it. I had the idea of combinatorics and I had worked on them for a long time, long before I knew Barton [D. E. Barton, the coauthor of her book, later to become professor of computer science at University College] or taught Barton … but I took him on because it was time that the thing was finished. So we got to work and he did all the fancy work, proceeding to limits and things like that. He was a good chap. We wrote quite a lot of papers together.

She eventually came to the United States, where she was on the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley, and succeeded Neyman as chair of the department. She left Berkeley to found and chair the statistics department at the University of California, Riverside, in 1970. She “retired” in 1977 at age sixty-eight and became an active professor emeritus and research associate in biostatistics at Berkeley. The interview that provided many of the quotations in this chapter took place in 1988. She died in 1995.

In 1962, F. N. David published a book entitled Games, Gods, and Gambling. Here is her description of how it came about:

I had lessons in Greek when I was young and … I got interested in archaeology when I had a colleague in archaeology who was busy digging in one of the deserts,

I think. Anyway, he came to me and said, “I have walked about the desert and I have plotted where these shards were. Tell me where to dig for the kitchen midden.” Archaeologists don’t care about gold and silver, all they care about are the pots and pans. So I took his map and I thought about it and I thought this is exactly like the problem of the V-bombers. Here you have London and here you have bombs landing and you want to know where they come from so you can assume a normal bivariate surface and predict the major axes. That’s what I did with the shard map. It’s curious there’s a sort of unity among problems, don’t you think? There’s only about a half dozen of them that are really different.

And Florence Nightingale David contributed to the literature of all of them.