IT WAS STILL LIGHT on Monton Street; its sunned bricks smooth, bloody; its strip of sky thinner and bluer than the one over Wythie. The neighbourhood was gridded and treeless, black and white, loud of a Saturday. Open doors, open windows, weekend music. Stuff Jan knew. From an entry corner she watched three taxis make drop-offs – each gone before the next arrived with another feller in a panel tracksuit over skivvies. They entered the last house; two came out quick – with their hair, their walks, like dressed-down punk rockers. One clocked Jan staring and crossed over. He had a bandy run.

‘Ay, smiler.’ Up close he passed into the entry after showing her his empty mouth. It smelled like Bully’s blanket. He shrank into the distance and she looked until Loose Ends’ ‘Hangin’ on a String’ seeped across the road and turned her head.

Jan stepped out and knocked on the end terrace.

A white girl her own age with a coldsore and a crimped mane answered the door and showed her in. This girl had blinked slowly at her first. A bloke’s ratty maroon jumper hid her hands, her shape, before Jan followed her chalk-stick legs sleepwalking up the stairs. The narrow dosshouse went tall. Old air choked with mildew, hash and curry. Slug trails glittered to a leak above where plaster and paper had curled into scraped butter. Through a hole Jan spied between floorboards: a bright inch. . . then eclipsed. She looked down in time to dodge a tipped Henry Hoover. His nose strangling the antique banisters like a python.

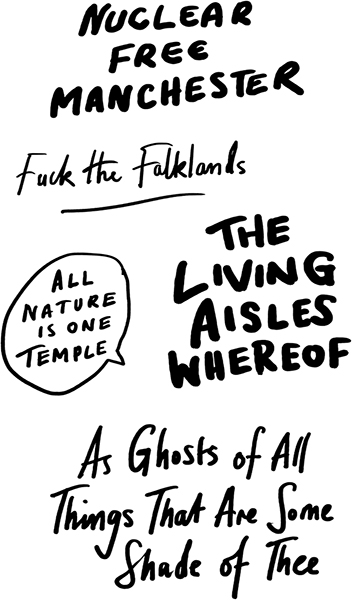

Speech-bubbled felt-tipped slogans and quotations followed them along the next flock wall between Care Bears and unicorns:

Here the girl stopped on the second small landing and pointed her to an open room. The girl and the house under the same spell: this weird dream-quiet, full of listening.

Jan peered into a cramped red office. ‘You Rodney Westlake?’

‘Come in, love.’

From inside she saw a long black-and-tan cowboy rifle propped against the radiator under the window. ‘What’s that for?’

‘Any aggro.’ The man stopped reading a salmon newspaper to glance at her, then the gun; then he smoothed the page on his desk. ‘See, I don’t do too well with me mitts.’ He started the next column. ‘It got used that thing for scaring birds off the airport runway. You know them pigeons what get stuck in the plane engines? Stops nice girls like you from going on their holidays. You see, that thing keeps the birds safe, the planes safe, the nice girls safe.’ He squinted up again. ‘You ever been on a plane, love?’

‘Never.’

‘I’m gunna go Concorde soon. Am saving up. And no fucking feathers’ll stop me.’

His beard had colour but he had shoulder-length grey curls. Thin on top. Thin thatched arms with blurry tattoos. Braces and a string vest. He could’ve been forty or seventy. Extending his desk were turrets of half-squished cardboard boxes for foreign radio sets.

Behind her now Jan heard the other girl’s tread. The girl stooped, came nearer, then froze. She had blistered lips, not a coldsore: ‘Puss, puss. . . puss, puss. . .’

There was a squeak, maybe another floorboard.

‘Is she all there?’ Jan said.

‘She used to be,’ he said.

The girl blinked slowly and left.

The man thumbed a razorblade off the desk and scored-out a salmon square and put it to one side. Jan stood close, aware of the silence, reading upside down.

‘They wanna do a Manchester edition of this,’ he said, creasing the paper and putting it to one side. ‘See, it’s just London classifieds. Southern nutters tryna flog their southern shite. Your uncle Mac brung it up with him from London.’

Jan heard another squeak and crouched. A sleepy grey kitten wobbled across a folded blanket under the desk. A saucer and milk bottle to one side.

‘Some skaghead give it us that puss-puss instead of cash. I’m too soft, me. I’ve always been soft. It’s why the cheeky cunts call me Madam. But see I can’t sell it round here, can I? Might pop an ad in the M.E.N.: Give Wee Moggie The Good Life. No Time Wasters.’

Jan scooped up the kitten.

‘The girls wanna name it Duchess but I think it’s a tom.’

Jan let it walk off her hands. Jan felt fingers in her hair, on the back of her neck. She stiffened but didn’t flinch – just held the chrome-tube leg of his chair. ‘D’you know me brother Kell?’

‘Aye, I do, love. Your uncle’s been bringing him round. But me and you’ve met before.’

‘When?’

‘You won’t remember. Too young.’

‘Me dad’s funeral.’

‘Well done. Can you remember?’

‘No.’

‘Plenty rum buggers what was after your daddy and granddad. Funny they all got pipped to the post by some kids driving home for Christmas pissed. Bet that’s how your nana tells it, anyroad.’

Jan rose and shed his hand but it caught her waist and she looked to check if the door was still open and it was. Some bloke and another girl, crossing on the stairs, gone. ‘Is me uncle here?’ she said.

‘He’s out tonight, romancing. Wouldn’t say who. Become quite the gentleman, has Mac. Mind you, he always had soul. Be what made him such a terror in his day. See, when he were working for Jim Dodds, he could go overboard, I mean, with his mitts, just so he’d have more to repent. Your dad were a bit like that. Worse at times. But, see, as big as Sefton was, he wasn’t Big Mac.’

The window was shut – the street’s music cut to a throb. Jan saw another taxi go, heard the kitten mewing, then life enter and leave other rooms: shoe steps and voices and skin and mattress springs and short-breaths behind walls.

Rodney touched her arse so lightly Jan had to pull away to be sure. Slowly she reversed to the door then shut it then came back. This time he didn’t touch her at all, looking up at her harder instead, working her out. His face began to blur and she stared through the window again, its light not faint or even turning but better than the room’s. She said: ‘The neighbours never kick off?’

‘We get cabs pulling up right through the week. We get allsorts, they come and go, wanting a wrap or a screw. You might have your grasses in Wythie but no one speaks to the dibble round here. You see, we hate them more than we hate each other. . . Now. What’s it you’re after?’

‘Kelly.’

‘You any better than him at maths, love?’

‘Y’what?’

‘If I get two fifty’s worth of skag laid on and I keep fifty for me health, how much do I need to sell the two on for, not to recoup, but to double me dosh?’

‘Enough to fly Concorde.’

He smiled. ‘You know what your brother’s getting mixed up in? That what you’re here about?’

‘I don’t want our Kell robbing for you. This big job. This jewellers. Just tell him to fuck off next time he’s round. He’s shit anyway. He’s not meant for it. I’m telling you. He’d wind up getting you all pinched.’

‘That right?’ Again he travelled her with care, her top half now, and with more interest, of which she was glad, since she was on. His movements clipped and exact. ‘I said to Mac: Dodds men are bad luck.’ Then Jan found herself weighing his left hand, inspecting a stump fingertip glazed smooth, nail-less and black. ‘Your old man done this, you know, love. In the Silver Birch, after shall we call it a minor disagreement. Done it with Jim’s lighter.’

He led her across the landing and opened a dusty blue boxroom with a camper bed on which the girl with blistered lips had curled asleep. Her fists against her knees. Right ear pressed into a skinned pillow. A topless bloke came out of the blind corner and sat at her feet, hunching over to toke from a glass pipe. He fogged the room lazily, stroking the girl foot to thigh. She didn’t shift but her expressions phased, her face more awake in dreams than out. Jan saw them: read her passions, clear behind the clouds.

Rodney shut them in, ready to try another bed but Jan knew none was free. He laughed on her a little and his breath was sour but no more than most lads. He had her pressed against the graffitied flock wallpaper. When he turned her face to lick her cheek, it was then she saw him –

Kell, stood in the office doorway, aiming the rifle at them from his waist.

‘Now, now,’ Rodney said, seeing with her, their faces pressed together.

Kell with the rifle still and still to move. ‘That’s our kid.’

‘I’m telling you now, son. Don’t get daft.’

Rodney left Jan at the wall and went to him and held the rifle with him and they didn’t fight for it just held it between them two-handed and once they had it pointed high enough Rodney twisted and pushed and Kell having been twisted and pushed onto the landing he looked round to catch himself – grabbed for the banister rail – but Rodney twisted and pushed again and then the rifle was his and he kicked for Kell but Kell was already tumbling down the stairs. Her brother rounded the corner and the thud-thud moved the house. Brought some girls out of their rooms, to gawp at Jan, who was glued to the wall and trying to scream; those dopey girls posed there on the landing, beneath its swinging paper-globe lamp.

Rodney kept the rifle trained down the empty stairs. ‘Speak now, Kelly Dodds of Wythenshawe, if you’re still with us!’

Kell’s groans and coughs came up the stairs.

When she heard them she shouted him but couldn’t move off the wall.

Rodney looked at her then, his shoulders rounded. He seemed to be itching all over. ‘It’s not loaded.’ He propped it in the corner, then he wiped his tattoos, wiping his arms like there were spiders climbing them. In outstaring him Jan freed her body inchmeal. He returned with the rifle to his office, muttering, ‘Puss, puss. . . puss, puss. . .’

Zuley came home and found them on the top deck outside her Hulme flat. Jan saw she had her keys in her fist. A crop jacket blew open and her belted frock had fluttered along the Crescent’s curve of dinted door after door – white stairwells spaced like knuckles jointing an endless finger. Kell wouldn’t let her near. Jan tried to read them: wordless traffic between their features, their bodies. Zuley stared up at him until he turned and lent on the low concrete wall and dangled his fringe over the courtyard, the Crescents vast and hushed. Across Jan saw ring-rows of glittering windows winding like gold sand through ears of Blackpool shells. Jan saw below: a car battered to tin foil, a thirsty green, heaped binbags hugging pillars and trees. Empties skittling everywhere. She smelled bonfire on the breeze. There was another car, of black bones, and Jan closed her eyes and saw sheets of flame.

Zuley took her by the hand and led her inside.

And Kell followed.

Her place smelled like blown candles and Impulse body spray. The telly had been left on with the sound right up: Tales of the Unexpected’s end credits’ girl was dancing in blood silhouette. The front room was plastic furniture, stacked records, a rainbow of drying clothes. Jan sat on a pink woolly mammoth rug glittering with cat hairs which itched her legs and palms. From it she unearthed one can of Lustrasilk and a lost spliff.

Kell perched, bruised and cracked, behind her on the settee arm, and stared down the hanging mirror. He tried to peel his T-shirt but the pain restricted him and his patience went before he got it over his elbows. Jan jumped up to help. A look kept her away. He heel-kicked the settee, split his T-shirt neck and Hulked off the rags. Jan went from wanting to cry to wanting to laugh. Burning liquid sloshed unspilt behind her face while he rolled his right shoulder, drew his left hand around his ribs and winced.

‘Our kid.’ Kell spoke to her in the mirror. ‘Put some tunes on.’

‘Wish I lived round here,’ Jan said.

‘You don’t get to sleep much,’ Zuley said bringing her a brew. ‘Never know what you’re missing.’ The way she sniffed steam from the cup made it seem special. Like potion to fix everything. As good as her grin.

‘What?’ Jan said.

‘Your hair. Looks dead nice like that. Wish I could towel-dry mine.’

Before she could say But I love your hair, or even just Ta, Zuley had passed her to give a cold can of Red Stripe to Kell which he tossed into the settee dip. Jan switched off the telly and reburied the spliff in the rug. Took her brew over to the records sandwiched in a wheelie cabinet with the player and speakers above.

‘How bad’s it look?’ Kell said to Zuley –

who got behind him to kneel sideways on the seat cushion to explore him. To touch red black blue, first softly with her nails and then again, rolling the cold beer can over each colour.

Jan watched this ritual awhile, then pulled music, then held up the sleeves, making sure to cover the names. ‘Oi, Kell, what’s this?’

‘Cymande, “The Message”.’

‘And this?’

‘Skull Snaps.’

She played the next one first.

He nodded to it, soothed. ‘. . .Wait. Sandy Kerr, “Thug Rock”.’

Jan cupped her brew with her back to them and just listened.

‘We’ve danced to this in Legend,’ Zuley said.

‘Night we met.’

‘Nice try, love. You met us in the Reno.’

‘And I said to you then: don’t get too romantic.’

Zuley opened the Red Stripe and drank. ‘Am worried you’ve broke summat and you don’t know it.’

‘I know it.’ And she gave him the can and he finished it in two.

‘He fell down the stairs,’ Jan said.

‘Whose?’

‘Uncle Mac’s.’

Kell looked at her, wilted. ‘Ask our kid why was she there.’

Zuley looked at him. ‘Why were you? You stood me up!’

‘. . .’

‘Not cos you wanted this uncle and whoever to batter someone with you? Not to give you that dock-off gun he’d showed off to you the other day?’

Kell announced it: ‘Patrick Somerville. Teaching at Poundswick. His missus put his name in that book he give you.’

Jan twisted away again, saw the needle running out of record. ‘I’m not telling you where he lives.’

‘Don’t you worry, our kid. I’ve put word out. We’ll be on his doorstop tomorrow.’

‘You’re being a right prick, Kell, you know that?’ Zuley said.

‘I know,’ he said.

‘How you getting Jan home?’

They talked at each other like this and Jan notched up the music and rummaged through more.

Polaroids slipped out of Terri Wells’ ‘I’ll Be Around’.

A dozen showed them in this flat, in this room: against the wall, on the settee, over the rug. Taking turns with the camera.

disco-glitter eyeshade –

dancing legs parting

a frilly bra draped over her brother’s ears, worn as headphones

a dark grinning cheek unscarred, blazing in the flash

dizzy angles made their bodies into mysteries

gave them fun-house proportions

the two of them stripped and shaped to each other

perfect somehow

for loving.

Jan left each Polaroid out to remind them.

Jan left, her brew untouched.