With money arriving in a pleasingly steady stream, and the prospect of more to come, in 1889 Charles moved into an apartment at 162 Great Portland Street – the house where Baroness Orczy, writer of the Scarlet Pimpernel novels, had once lived while in her teens. Although this grand house was only a stone’s throw from Great Titchfield Street – where he retained his business premises for the time being – Great Portland Street was a much more prestigious address. In what may have been a conscious effort to present himself as a respectable, upright citizen, he made sure he was included in the electoral register and in commercial directories. And, as icing on the cake, he began to put the letters ‘CE’ (Civil Engineer) after his name.

But Wells continued his patent business on the same principles as before, and was equally happy to receive money from wealthy as well as not so wealthy investors. Frances Budd, a single woman, lived in Worthing, Sussex. In March 1889 she noticed this advertisement:

GOLD MINE (Better than a). — A very large sum

can be realised at once with a very small sum, in a safe,

honourable way; good security given. — Write for full particulars

Gold Mine, May’s Advertising Offices, 162, Piccadilly.

Wells told her that he needed £30 to produce a motor for small machines such as knife cleaners, coffee mills and boot polishers. In his words, the gadget was intended ‘for domestic and general use, cheap, safe and desirable’. Of course, the investment would ‘just suit a lady’. He forecast that it would bring in a return of £600 (£60,000) per year for Miss Budd. As funds were limited, she asked whether she could purchase half of the quarter-share advertised. Wells said he could not do this, because he ‘offers the patent for security’. She then forwarded the initial payment of £5, and promptly received the receipt for the provisional patent application. (Like Dr White a few months previously, she also believed that this was the patent certificate itself. And Wells had carefully omitted to mention that he was already dealing with several other people in connection with suspiciously similar inventions.)

Application date |

Title |

Patent No. |

18 March 1889 |

Motor |

4694 |

21 March |

Spirit motors |

4945 |

23 March |

Motor |

5070 |

2 April |

Petroleum engines |

5633 |

Miss Budd finally scraped together the balance of £25, and sent it to Wells, who wrote to say that he would start work on the invention immediately and would keep her informed periodically as to progress. And that was the last she heard from him for some time.

She became increasingly concerned. The £30 had been more than she could really afford, and the lack of news from Wells was disquieting, to say the least. As her letters to him went unanswered she travelled to London in July to see him in person, but when she reached the Great Titchfield Street premises, he was not there. She wrote again, threatening to put a solicitor on to the case.

Wells replied that he would not try to stop her, but that he had been in Paris trying to sell the idea. Then Miss Budd received a further letter from him on 17 October. He claimed that his only fault was that he hadn’t been able to sell the patent. He told her that she could not receive her money back but that he would send her a share. Although she was not satisfied with this answer, she decided not to involve a solicitor after all, as her friends had advised her not to throw good money after bad. Finally, she contacted the Patent Office in early 1890 and discovered that only a provisional patent had been taken out, and that it had now expired.

Finally realising that the ‘patent certificate’ she had received from Wells was nothing of the sort, she wrote to tell him that she knew the scheme was a swindle and she would prosecute unless he returned her money. Wells politely assured her that he ‘always respects a lady and regrets her action’.

Along the coast at Bournemouth, Dr White had long since lost all patience with the affair. Having sent his £30, he had received a reassuring letter from Charles Wells to say that experiments were progressing, but he quickly formed the opinion that in reality nothing was happening at all. After threatening legal action he received ‘a very unsatisfactory answer’ from Wells, who began by saying that White had behaved in an ungentlemanly manner by setting a solicitor on to him without warning. He gently reproved White for doubting his honesty, adding that if he, Wells, had to pay lawyers there would be less money available to perfect the invention. Then, in December 1889 – some five months after receiving White’s investment – he had written once more to say that the invention was ready and could be seen working. Wishing to have nothing more to do with Wells, White had contacted his solicitor again to see what could be done about getting his money back. The lawyer responded by sending him a copy of a weekly magazine called Truth. This particular issue contained a damning exposé of Charles Wells and his patent schemes. Dr White, stunned by what he had read, had then made contact with the police.

Truth magazine was the brainchild of Henry Labouchère, writer, publisher and Member of Parliament. He came from a privileged background and was educated at Eton. While at Cambridge University later, he had managed to run up debts of £6,000 (£600,000) and was removed by his parents. Over the next few years he travelled to Mexico, where he fell in love with a woman who was a circus performer and he even joined the troupe himself. At one point he spent six months living with a tribe of Ojibwe Indians.

But by the late 1880s, he had become one of the most distinguished journalists in Britain, with a well-earned reputation for exposing swindles, scandals and injustices. Sometimes he was sued for defamation, but in most cases he won, and on the rare occasions when he lost he could easily afford to pay damages:

Armed at all points, he never strikes till he is certain that the blow will be crushing. Perfectly fearless, he is perhaps the only journalist for whom the law of libel has no terrors.

In early 1890, Labouchère wrote in his column that he was beginning to receive enquiries about C. Wells of 115 Titchfield Street, and had been prompted to investigate. His article, which stretched to a page and a half of text, quoted three of Wells’ recent press advertisements in full, and listed forty-two of his patent applications going back to 1887. Labouchère informed his readers that thirty-five of them had been abandoned, and conjectured that the other seven might well suffer the same fate.

’It costs only £1 to obtain provisional protection for nine months,’ he wrote. ‘Any twaddle that comes to hand does for this [and] I think I have said enough to make it desirable for ladies or gentlemen eager to make their fortune rapidly to “let Wells alone”.’ In the next issue of his journal he writes:

I never expose a trick or a swindle without at once receiving the thanks of immense numbers of unfortunate victims. The latest case in point is that of Mr. ‘C. Wells, C.E.,’ with his provisional patent trick. In response to the article in last week’s Truth, I have been favoured with several dozens of letters giving further details of Wells’s operations, many of them from solicitors who have been consulted on the subject. I am much obliged for all this information, and I need not say that I shall always have C. Wells, C.E., under my eye in future.

Soon Labouchère was publishing articles on an almost weekly basis condemning Charles Wells. On 13 March he alludes to the case of Dr White (without, however, actually naming him). When White’s lawyer had pursued Wells, the latter had replied that he had been ‘so much frightened by the interference of the solicitor that he had not gone on with the experiments, and that the time of the provisional patent had expired’.

Labouchère added, ‘I hear, however, of one case in which the victim is determined to bring the matter into a law court, and I look forward with considerable interest to that event, when C. Wells will have an opportunity of explaining his Patent Game before the Court and the public.’

Two weeks later Truth warned its readers, ‘not upon any account to have anything whatever to do with his artful patent game, to which I think the authorities of Scotland Yard ought to direct their special attention’. We can be quite sure that Wells was following this continuing saga in Truth, and we know for certain that he was in possession of this very issue of the magazine.

Little by little his advertisements stopped appearing in the newspapers – including The Standard, which had previously carried them on an almost daily basis. Perhaps Wells himself had decided not to push his luck too far following Labouchère’s exposé. But it is just as likely that the papers in question refused to print his announcements because of the adverse publicity which might arise. Others, though, continued as before: The Times, for example, regularly carried Wells’ notices for months afterwards.

Far from responding to Labouchère’s call for police intervention, the authorities failed to act. In part this was because fraud was difficult to prove. Wells could have argued that he had only the best of intentions when he invited people to invest their money in his gadgets. If it turned out that some of them did not work, or if it proved impossible to find a buyer for the patent, that was not fraud – it was simply bad luck. In nineteenth-century Britain, businesses, financial schemes and advertising were largely unregulated: the responsibility to make sure that the scheme was sound rested on the investor’s shoulders. And to secure a conviction for fraud, it was not sufficient to show that Wells had promised something that he later did not deliver. The prosecution had to prove that the accused had knowingly made a false claim about past events.

If a man says, ‘I intend to prospect for gold in Australia – invest £1,000 with me and I will make you a millionaire’, it is unfortunate if investors lose their money, but no fraud has taken place. But if a man says, ‘For the past ten years I have mined ten tons of gold annually: invest in my goldmine’, a fraud has been committed if that claim of past events is deliberately untrue, and if the investor can be shown to have relied on the claims. It can be notoriously difficult to prove intent to defraud, because who can say what a man’s intent was, especially if those thoughts went through his mind some years previously?

The police had better things to do with their time than pursue cases that might very well be thrown out of court. Besides, they had their own internal problems to deal with. Aside from a general reputation for inefficiency, they had suffered from bad publicity in the past when their own officers were convicted for corruption. Lately, they had failed completely to solve the infamous ‘Jack the Ripper’ case, after which the commissioner of police, Charles Warren, had resigned. Scotland Yard was in disarray, and it is probable that at the beginning of the 1890s the force thought it could best regain public confidence by concentrating on those cases where there was a good chance of securing a conviction.

The fact that the police ignored Labouchère’s call for him to be prosecuted must have left Wells feeling that his position was unassailable as far as a criminal action was concerned. And when it came to a civil claim, the clients who had considered suing him – such as Miss Budd – often concluded that it would be a waste of time.

It is evident that the Truth articles had not yet come to the attention of Miss Phillimore, who seems to have been the most patient and restrained of all his investors – despite having entrusted more money to him than any of the others. Since sending her £60 for a share in the steam engine patent in early 1889, she had received nothing from Charles Wells, except for a string of empty promises. In June of that year a letter came to say he was searching for a suitable boiler for the engine, and had no doubt about the eventual success of the venture. In October, he said he had been trying to sell the patent in Paris, though without luck so far. Every day, he added soothingly, brought the chance of success. In January 1890, he had written from Paris, to express his thanks for her patience and his hope that she would ‘speedily realise her desire’. After this, it would be many months before Miss Phillimore received another word from him.

Towards the end of 1890, a young aristocrat, the Hon. William Cosby Trench, of Clonodfoy Castle, County Limerick, Ireland, perused his copy of The Times. A classified advertisement under the heading of ‘Partnerships &c.’ caught his eye:

TWENTY-FIVE THOUSAND POUNDS positively paid in four months, plus large yearly income, to purchaser of share in an important patent. Price £475 down. Fullest investigation offered. Write Security, May’s, 162 Piccadilly.

Trench later confessed that he knew absolutely nothing about business, or about patents, but this did not deter him from sending off for particulars. He received in return a letter from Charles Wells, C. E., of Great Titchfield Street (‘established 1868’) outlining proposals for an energy-saving steam engine.

Wells sent details of his latest machine, which he described as ‘a most important proven invention, a new method of obtaining motive power for all purposes, but especially for propelling ships and boats, for the reason that a large amount of cold water is necessary’. The invention, he explained, could be fitted to ships like the Rodney – a large battleship launched two or three years earlier. The navy would pay a substantial royalty to use the patent device. As his invention would produce a fuel saving of up to 60 per cent they would recoup the costs in the first year.

Apart from knowing nothing of business or patents, Trench also knew nothing about engines. But it was common knowledge that any such discovery would be immensely valuable. Trench was interested, but was sufficiently cautious to write back to Wells for more information: in fact, a fairly lengthy correspondence ensued. Wells told him that he had conducted numerous experiments, and could fully understand that Trench might have concerns, and said, ‘when a man saw the certainty of a fortune in his grasp he might be excused for being anxious.’

Trench sent off the customary £5. Wells replied, enclosing what he called ‘the official certificate of patent’, dated 22 December 1890. As for the £470 balance, Wells added that he ‘would be very pleased if he [Trench] could arrange to let him have the money before Christmas’. However Trench was perturbed when he saw the newspaper advertisements continuing to appear, after he had agreed to fund the project. Before sending another cheque he questioned this with Wells, who calmly replied that the series of advertisements had been booked in advance and had not yet run out. Wells said the replies that were still coming in would not be wasted, as he hoped to interest the applicants in another of his inventions, which related to a new electrical discovery he had made.

On New Year’s Eve, satisfied at last that the investment was a sound one, Trench sent his cheque for £470, ignorant of the fact that Wells had filed an almost identical patent application only a few days previously. In fact, during the course of the year just ending, he had submitted no fewer than nine separate patents for steam engines, three for hot-air engines and one with the vague description of ‘steam and hot-air engines’.

Instead of allowing the series of advertisements to run out, as he had promised Trench, he actually inserted several entirely new ones:

MONEY MAKES MONEY. — How to earn a very large sum in a few weeks with a very small sum, by investing in a genuine, honest, reliable way. Security given. For full particulars write Bona Fides, May’s, 162 Piccadilly.

And then, on 6 February 1891, Wells was back with a more generous offer than ever before:

THIRTY THOUSAND POUNDS in three months, and probably more yearly, is the certain product of a SHARE in a PATENT. Extraordinary low price, £500 cash. Write Necessity, May’s Advertising Offices, 162, Piccadilly, W.

The results from this last advertisement were disappointing. For most readers the promise of a sum which would today be worth about £3 million must have seemed too good to be true, and no one was gullible enough to reply to it. No one, that is, except the Honourable William Cosby Trench.

A comical situation now arose. Trench did not realise that the advertisement had been placed by Wells. And, for his part, Wells did not immediately seem to be aware that Trench was already a ‘client’. He sent Trench another letter identical to the first one except that this time £500 was requested, not £475. Then, two days later, he wrote in respect of Trench’s first investment to say that the forgings and castings for the machine were nearing completion. Trench now added to the confusion by stating that a friend of his was interested in buying a share of the patent. Wells seemed glad to hear this news: he informed Trench that the ship which was to have had the new engine fitted had sunk. He, Wells, had been compelled to buy another, and thus the opportunity arose for a third party to join them. Another gentleman had applied to take a share, he confided, but Wells said he would prefer Trench’s friend. The outcome was that Trench sent Wells a further £500.

During these first weeks of 1891, Wells made four new and entirely separate patent applications in respect of steam engines, and another for ‘galvanic batteries’. Not one of these was ever taken beyond the provisional application stage. On 14 March Wells registered an invention for obtaining ‘motive power from exhaust of steam engines’, but it would be one of the last he ever delivered to the British Patent Office. He intensified his advertising campaign but, with the exception of Trench, who seemed determined to thrust large amounts of cash into Wells’ hands at the slightest provocation, it was becoming evident that it was the patent scam itself that was running out of steam.

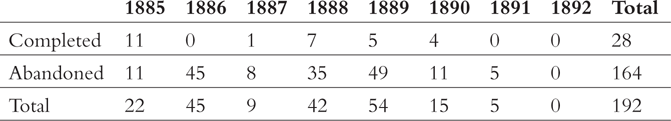

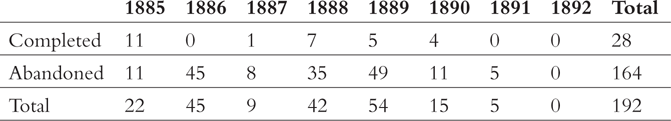

Reviewing his applications to date, it is plain that overall Wells had only ever completed one in seven of the patents he submitted – in contrast to a national average of one in two:

As these figures show, Wells’ activities in connection with patents reached a peak in 1889, when he made fifty-four applications, but dwindled to almost nothing in 1891, finally ceasing by 1892. The character of the inventions had also changed. Whereas in the earlier years he had applied for a very mixed bag of patents – from balloons to bows and arrows – from 1890 onwards it appears that he had lost interest in dreaming up fresh ideas, and from that point his submissions were uniformly described as ‘steam engines’.

Several years had passed since Charles’ wife and daughter had returned to France. But in about 1890 he met the love of his life – a striking young French woman named Jeannette Pairis. She had dark eyes, ‘a pretty pouting mouth’ and brown hair in a long plait which reached down to her waist. According to some accounts, she was ‘an artist’s model from Chelsea’.

This seems to have been one of those instances where ‘opposites attract’. Jeannette loved to wear new clothes, hats, jewellery and shoes, while Charles pottered around in a threadbare old suit. She enjoyed champagne and fine food, yet he was quite content to dine on a couple of boiled eggs he had prepared himself. In age, too, there was a wide gap. At 21 she was much younger than Wells, who was approaching 50.

He was old enough to be her father – he actually was born a few months before her father – and, for her part, Jeannette was several years younger than Charles’ daughter. Yet they seemed oblivious to the age gap and were plainly besotted with each other. As Dr Francesca Denman explains, ‘Psychologists talk about men who want to be young forever and young women are a way to do this.’ And other sources confirm that he always had a penchant for ‘little ladies’.

As we have seen, Charles Wells had begun to phase out his patent scam, and was already preparing for the next money-making endeavour. And it seems likely that Jeannette’s arrival on the scene may have had something to do with this change of direction. Having expensive tastes, perhaps she perceived something that he did not – that his patent business simply was not making enough money. Maybe it was she who came up with the next big idea. But while his mind was occupied with future plans, Wells still had Trench as a willing backer, and made the most of the opportunity.

Wells had begun to spend more time on the Continent than in London. From Marseille he wrote to Trench to say that he was making ‘splendid openings’ there regarding the patent. In April he wrote again enclosing a statement from a Monsieur Georges Thibaud, whose engineer had inspected the machine and given a glowing report. On the strength of this, Wells invited Trench to take an additional share in the French patent for the sum of £1,250 (£125,000). On the sale of the patent Trench was to receive £50,000 (£5 million). Trench replied with alacrity, enclosing a cheque.

The next letter was from Paris and was dated 3 May 1891. Wells said he was setting up a Franco-Belgian company to exploit the patent, and needed £2,500 for the purpose. As he only had £500 himself he asked whether Trench would put up the other £2,000. He said Trench must not think he would be upset if he couldn’t do this, as he (Wells) could easily get the money elsewhere, but he wanted to give Trench first refusal.

Up to this time the two men had never met, but later that month Trench went to the Great Titchfield Street premises, where Wells showed him a model of a steam engine, explaining that this was the invention he had put his money into. Trench seemed confident that the machine would be a success, though he said he was not sure that it would generate such immense profits as Wells had forecast. But Wells assured him that it would. This seemed to satisfy Trench, who left a cheque for the sum of £2,000.

Trench received another letter from Wells on 24 June – this time from Turin. Wells stated that he was going from there to Vienna and then Paris to form one large company. He promised Trench that for a further investment of £2,500 he would later receive £25,000 in cash, together with shares in the new company worth £50,000. Trench duly handed over the money and Wells informed him that this would bring his shareholding up to £225,000. To back this up, Wells actually sent several ‘share certificates’, as he described them. These showed Georges Thibaud to be the president of the company.

In July 1891 Wells invited Trench to London to watch a demonstration of his invention. The trial involved a small steam launch which Wells owned, Flyer, and took place on the River Thames near Charlton Pier. It was not a very salubrious setting. This stretch of the river was lined with chemical works, plants for processing guano from Peru, factories for paints, dyes, rubber and gutta-percha, sewage works and chemical refineries. Although raw effluent was no longer pumped into the river, the Thames was still a repository for all kinds of household rubbish, industrial waste and even dead animals.

Trench later recalled, ‘I went on board. We went down the river for about twenty minutes. He [Wells] said he had the engines on board, but I could not see them.’ It did not occur to Trench to check the most elementary piece of evidence – the amount of coal used. Nor did he question Wells about the fuel consumption. ‘I was satisfied with his assurance that it would turn out a success. I could not estimate if it saved coal, and I learned nothing from the trip.’

Wells himself gained rather more from the outing. As the diminutive craft chugged up and down the river, Trench was a captive audience. Wells regaled him with expansive details of the new French company he was setting up, for which he would need more capital. He was going to make the journey to Paris in one of his own boats, he said, and Trench asked if he could accompany him. Wells agreed to this, but whenever the subject was mentioned again he always made some excuse.

By now, though, the funds which Trench obligingly supplied were Wells’ main source of income. His investment had reached £6,750 (£675,000), and he was the only ‘client’ to have parted with any really substantial amount of money. But still it wasn’t enough to launch the project Wells had in mind. On 21 April Wells inserted his most ambitious advertisement to date, offering a larger reward than ever before: the equivalent of £5 million. But this time, it seems, he had gone too far; if anything, the advertisement smacks of desperation:

FIFTY THOUSAND POUNDS positively paid before four months to the PURCHASER of a SHARE in a PATENT. Price £1,250. Ample security given for the £50,000. Write Engineer, May’s, 162, Piccadilly.

Apart from William Trench, the backers had all advanced relatively small sums to Wells: Frederick Goad had handed over £25; Dr White, Mrs Forrester and Miss Budd had each contributed £30; Miss Phillimore £60. His annual revenue – before Trench came on the scene – cannot have been much more than £1,500.1

On the other side of the balance sheet, his outgoings were heavy, and he continued to take on ever greater financial responsibilities. While retaining his business premises at Great Titchfield Street, and his luxury flat at 162 Great Portland Street, he now signed the lease on a much larger commercial building, too. This imposing five-storey corner property at 154–156 Great Portland Street was just a few yards from his apartment. It had a 46ft façade on to Great Portland Street itself, with several shop windows. The ground floor was sufficiently roomy for Wells to have a very old, full-size traction engine, ‘nicely painted to give it a good appearance’, driven into the showroom, where it could be admired by passers-by. The rest of the building consisted of both business and living accommodation on a grand scale. But it was expensive. Wells paid £800 for the new lease (£80,000) and was committed to an annual rent of £200 (£20,000).

Wages and salaries for Eschen, two or more other engineers and a couple of clerks accounted for at least £300 per annum. Expensive models were made in support of at least some of his patent applications, and there was an enormous advertising bill, as we have seen.

His private outgoings were also huge. From 1888 onwards, he had bought and sold a succession of boats, often owning two or more at the same time. They included: Kettledrum (a 55ft steam yacht); Ituna (a 137ft steam yacht); Wyvern (a 60ft steam yacht which was wrecked while in Wells’ ownership); and Flyer (the small steam launch in which Trench had been taken up and down the river). The yacht Isabella was also in Wells’ possession for a time. On another vessel, Kathlinda (a 93ft steam yacht), he already owed money for repairs, rent of moorings and so on: the outstanding debt on this boat alone eventually reached nearly £600 (£60,000).

And to add to his business worries, some of his ‘investors’ were becoming agitated, and wanted to know what he had done with their money. Some even called at his place of business. On one occasion Eschen answered a knock at the door, and Miss Phillimore stood there, asking to see Mr Wells. But Eschen was under strict instructions. ‘When people came asking for Mr. Wells I let them in,’ he later said. ‘If he was not there I did not.’ Miss Phillimore went away empty-handed.

And then, of course, there was Jeannette. Her shopping bills were already a drain on his finances. Yet he wanted to please her, and to impress her, and so he decided to buy another yacht. Not just an ordinary yacht like those he already owned. His new acquisition would be a truly spectacular floating palace to rival any vessel afloat. And he knew it would be hugely expensive.

Wells went to see an acquaintance, a man calling himself Aristides Vergis, although this is unlikely to have been his true identity. Vergis was a man of no fixed address – or name, or age, for that matter. He had recently served a twelve-month sentence in Pentonville Prison, having been found guilty of obtaining a large quantity of valuable jewellery by false pretences. On his release he had set himself up as a yacht broker with upmarket offices in London’s fashionable Sloane Square2 – probably financed with his ill-gotten proceeds from the fraud.

Vergis told Wells about a ship for sale in Liverpool. It might possibly be suitable for conversion into a large pleasure craft. The vessel in question was Tycho Brahe,3 an iron cargo ship of 1,633 tons, built almost a quarter of a century earlier. Motive power was provided by steam, but she had two masts and a full set of sails, and, like many ships of her era, could be propelled by either the wind or by her engines, or both (Plate 5).

She had undoubtedly seen better days, having spent most of her life on the gruelling transatlantic run between Britain and South America, carrying coffee and other cargoes. But at 291ft in length she would be one of the largest and most impressive yachts in the world. In short, this was just what Charles Wells was looking for. She was being sold at the knockdown price of £3,500 (£350,000), but would need a much larger sum than this to turn her into a luxurious pleasure craft.

Despite the seeming impossibility of the task ahead, Charles agreed without hesitation to buy the ship. At the same time, he appointed Vergis, the professional yacht broker and fraudster, as his agent for all maritime matters.

His latest money-making scheme would take care of the balance of the money to complete the purchase, Wells considered. But it needed £6,000 in start-up capital. He first tried to resolve this chicken-and-egg problem by placing an advertisement in The Times, inviting readers to lend him the money. Provided at least eighty people advanced £75 each, he would be home and dry:

SEVENTY-FIVE POUNDS LOAN REQUIRED, immediately, for a short period. Full security and 15 per cent interest given. Safe investment. Only private investors treated with. Write Security, May’s, 162, Piccadilly.

In the event, Wells didn’t even wait for the replies to come in. Possibly the funds had unexpectedly materialised from another source. At any rate, by the time the notice appeared in print he had somehow acquired £4,000 capital and was already on his way to the place with which he would be associated forever after – Monte Carlo.

______________

1 From the beginning of 1887 to mid-1891 Wells had filed about 100 patent applications, and presumably each application represented another new investor.

2 The office was almost adjacent to the bank where Wells had an account. Sloane Square is located in the Chelsea-Fulham-Brompton area of west London, where both Charles and Jeannette seem to have had many connections.

3 The vessel was named after the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546–1601).