Charles Wells’ advertisement in The Times, 7 September 1891, inviting readers to back him at Monte Carlo.

News of Charles Deville Wells’ success at Monte Carlo took some time to reach Britain. It was not until Saturday, 1 August that a first brief report appeared in the newspapers:

GAMBLING AT MONTE CARLO

MONTE CARLO, JULY 31.

An Englishman named Wells, who is staying here, has just had a run of luck so extraordinary as to be the chief topic of the hour, not only with those who frequent the Casino, but among the residents of Monte Carlo generally … He won several stakes of 26,000 f, and twice consecutively backed the number one ‘en plein’ successfully for 8,000 f, the maximum amount allowed. He also frequently backed with similar good fortune the even chances – red, odd and even, ‘marque,’ and ‘passe’ – and more than once won all these stakes at the same time.

A follow-up report appeared on 3 August, Bank Holiday Monday:

MONTE CARLO, AUG 2.

Mr. Wells … continues to be favoured by the same good fortune. Finding the luck turning against him, he had the prudence to quit the table at which he had been assiduously playing day after day from the opening of the Casino till its close. Before leaving the building, however, he risked a few stakes at another game, trente-et-quarante,1 and, winning each, continued to play till he had further increased his gains by the sum of 160,000 f, or close upon £6,400. Mr. Wells at trente-et-quarante follows the same system that proved so successful at roulette – the famous ‘coup des trois’ – that is to say, following the luck till he has won thrice in succession, and then withdrawing the accumulated stake. People here and at Nice are talking of nothing but his marvellous success.

Another journalist described how the table where Wells was playing ‘was surrounded by a large crowd, and intense excitement prevailed, such persistent good fortune having never been witnessed before’. Wells’ winning streak was beginning to have an adverse effect on the bank, the paper claimed, adding that Wells ‘keeps two secretaries to assist him in his transactions’.

Most readers enjoy a happy, good luck story, especially on a summery holiday weekend, and the reports struck a chord with the public. Charles Wells, ‘the lucky Englishman’, was both envied and admired. People reading his story would have loved to have accomplished what he had just done: but as they were unlikely ever to have a chance of doing so, they imagined what it must be like to be in his position, and admired him for having beaten the system. It was evident that his wins were not due to good fortune alone, but to his own strengths as an individual: his stamina, his cool-headed manner and his tenacity. And, unlike many other gamblers, he had been businesslike and had sent his gains home instead of running the risk of losing them again. Because luck was only part of the winning formula, he was seen as having earned his reward.

His reputation was by no means confined to Britain. Within days his name appeared in newspapers around the world, particularly in the United States of America and in Australia. Wherever his story was told, people wondered how Charles Wells had beaten the bank: had he really invented a foolproof system for gambling? Had he cheated? Or simply been incredibly lucky? Or was there some other explanation?2 Almost everyone had a different opinion, but no one actually knew. And before anyone had the opportunity to quiz him on his triumph he had left Monte Carlo.

His success at the gambling tables enabled Charles Wells to close the lid on his moribund patent business. For the past eight months he had not submitted a single new patent application, and those he had registered at the beginning of the year had not been completed.

In contrast, his plan to break the bank had achieved everything he had hoped for, and more. The money was welcome, but there were other advantages, too. He was praised in newspapers around the world, and within a few days he had achieved far greater recognition than his father had earned in a whole lifetime. And he was determined to return to the casino before very long. There was just one sobering thought. Even with his newly acquired wealth he could not afford to complete the purchase of the ship, and put his business affairs in order at the same time.

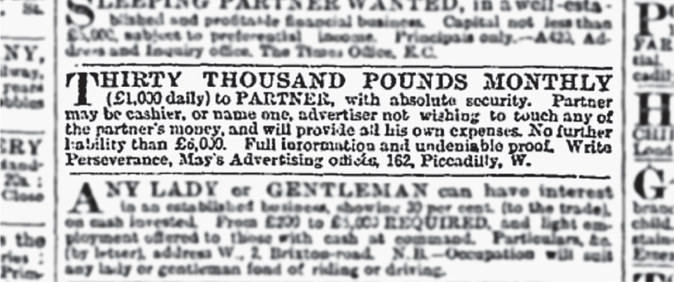

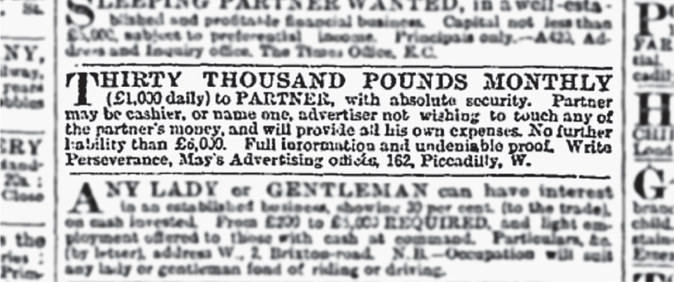

But in a flash of inspiration, he realised that there was a way to expand on his recent attainments, and during September and October he placed a new advertisement in high-circulation newspapers. The advertisement bears a passing resemblance to his earlier publicity, with its headline promising a large amount of cash. But this time, the offer was not a quarter-share in a patent. It was instead the opportunity to back him in his future gambling activities at Monte Carlo. And with this new scheme came the promise of a substantially larger reward than before: £30,000 – £3 million in present-day terms – every month.

The password, ‘Perseverance’, seems particularly appropriate in the case of Wells, who had plotted, schemed, worked and waited so long for success and fame to come. Wells now had a reputation as the gambler who had broken the bank, and was determined to exploit it to the full.

Charles Wells’ advertisement in The Times, 7 September 1891, inviting readers to back him at Monte Carlo.

The idea was inspired. It remains to this day the perfect money-making scheme. Wells is saying, in effect, ‘give me £6,000 [£600,000] to gamble with using my “infallible system”. If I win I’ll give you a return of £1,000 a day [£100,000]. If I don’t, the most you will lose is the £6,000 you have invested.’ Whatever happened, Wells himself could not lose. And the beauty of the stratagem was that – although it was distinctly shady – no one could possibly point to anything about it that was illegal.

We can picture him as he eagerly makes the 1-mile trip from his office in Great Portland Street to Willing’s Advertising Office at 162 Piccadilly – a 1s ride in a hansom cab. He is not expecting a flood of replies, as only a very small number of people have £6,000 in ready cash to invest. But on this particular day he finds an envelope waiting for him in his mailbox, and his pulse quickens.

Yet something about the letter seems familiar: the handwriting, the stationery, a faint hint of perfume, perhaps. As he tears open the envelope the truth slowly dawns on him. This is not something he has reckoned with at all. The sender of the letter is none other than Miss Catherine Mary Phillimore.

Not a single word had passed between Charles Wells and Miss Phillimore for almost two years. Having received her investment of £60, Charles had virtually ignored her, save for his letter of January 1890, in which he hoped she would ‘speedily realise her desire’. Since then, with so many other things on his mind, he had virtually forgotten her.

Miss Phillimore also had more pressing concerns. Her ageing mother, who was nearing the end of her life, doubtless took precedence over Wells, his inventions and the relatively small sum she had invested with him. In short, she had probably forgotten him, too.

But now she had answered his new advertisement, Wells’ interest in her was reawakened. This, he realised, could only mean that she must have £6,000 at her disposal – a thought that had never previously occurred to him. The very idea opened up distinct new possibilities.

The correspondence between them recommenced, with Wells enthusing in a letter about his recent Monte Carlo success. But Miss Phillimore seems to have been quite unaware of these exploits. Far from being impressed, as Wells had expected, she was horrified. She was a devout Christian who took a dim view of gambling, and she told him so.

Wells then explained that he needed the money to finance new projects, cheerfully adding that he ‘couldn’t have got through if the Monte Carlo affair hadn’t turned up’. Realising, though, that Miss Phillimore was unlikely to finance his future gambling activities, he skilfully changed tack, and sent her a long, highly detailed letter bearing his new business address of 154–156 Great Portland Street. He told her how successful he had been in other matters and said that he had invented another new device for saving fuel in steam engines. He forecast early results, explaining that he already spent ‘thousands’ on his present venture, and complimenting Miss Phillimore on her good fortune in being in a position to back his idea by purchasing a quarter-share.

He then went on to describe in rapturous terms the lavish new business premises and listed the various departments: ‘machinery in all its branches’ on the ground floor; offices on the first floor; a ‘chemical laboratory and testing department’ on the second floor; a ‘tracing room for models and patents’ on the third floor; and, lastly, an ‘electrical department’ in the basement.

He also wrote about the ship that he proposed to purchase once he had raised the money. The vessel would be used as a kind of travelling demonstration of his fuel-saving devices. A cargo worth £2,000 was already promised, he claimed, and in a single voyage the ship would earn £150. He added that he had thirty ships under his control, and claimed that by fitting his patent engine to all of these he would make a profit of over £1 million in just the first year. He told Miss Phillimore that he could have offered a share in this new invention to a company, but he would rather offer it to her, as a company might fail and that would be ‘an everlasting stain’ on his name.

He promised her a quarter-share of the revenue in exchange for an investment of £6,000, and assured her that ‘as for the £1,000 a day [as projected in his advertisement] it was the least part of the anticipated return’.

Miss Phillimore considered his offer. It sounded as if the ship represented good security, and she agreed to advance the sum that he needed – but on one condition, namely that the ‘loan of £6,000 was made to him on the distinct understanding that he never resorted to that mode of raising money [gambling] again’.

At almost exactly the same time Wells received another surprise in his mailbox at Willing’s. The Honourable William Cosby Trench – surely the most loyal reader The Times ever had – spotted Wells’ new advertisement. Unlike Miss Phillimore, Trench was fully aware of Wells’ gambling achievement – he had, of course, devoured every word of the recent press coverage. But although the notice in the classifieds bore a marked resemblance to those he had previously replied to, it did not dawn on him that Wells was behind it. ‘The advertisement I answered gave the address of Willing’s office,’ he said later, ‘and I had no idea I was communicating with Wells when I answered it. He wrote saying the matter was in connection with his scheme at Monte Carlo.’

Since Trench already knew about his gambling activities, there was no reason for Wells to beat about the bush. He told Trench he wanted a backer to put up £6,000 for him to gamble at the casino again, and wondered whether Trench was interested. He explained in glowing terms how he had devised a system which enabled him to win with certainty. While he was recently ‘in Italy’ to promote the patent machine that Trench was already financing, he had spent six days at the gaming tables playing with money provided by a person who had put up the stake money. He was at pains to let Trench know that his winnings had been £40,000. Although the profits had been so huge, he informed Trench that he had left Monte Carlo to perfect the invention that Trench had financed. But Trench was alarmed at the thought of Wells gambling with his money and – like Miss Phillimore – refused to entertain the idea. ‘I sent him no money to play the scheme with,’ he later emphasised.

As his two biggest ‘investors’ had both refused to back his next gambling expedition to Monte Carlo, Wells now had to rethink his approach. He decided that when he next received a response to his announcement in the paper, he would first send a letter describing in very general terms the fortune that could be earned by investing with him, but carefully avoiding any mention of Monte Carlo or of gambling for the time being.

It is believed that, to prove his bona fides, he sent his bank passbook to each applicant, together with a polite request in the accompanying letter for its prompt return.3 This was a gesture calculated to engender mutual trust between Wells and his prospect. Following his win at Monte Carlo, Wells’ account at the London & South-Western Bank in Sloane Square showed a healthy balance, with large sums credited since July. There can be little doubt that this was part of the ‘undeniable proof’ mentioned in his advertisement.

Once the applicant was well and truly hooked, Wells would move on to the second stage. For this he doubtless had an impressive booklet printed, describing the gambling ‘system’ he had perfected, detailing the potential profits, and probably quoting passages from recent newspapers about his Monte Carlo successes.4 In short, more ‘undeniable proof’.

But these over-elaborate measures did not work. A few other replies did come in, apparently, but no other subscribers are thought to have signed up to Wells’ new project. In fact, this is where his planning went off the rails completely: several people, on receiving his first letter outlining the scheme in the most general and non-committal terms imaginable, had reservations about the business. Instead of writing back to Wells accepting his offer of an explanatory brochure, they forwarded his letter to Henry Labouchère at Truth magazine.

With the new influx of funds from Phillimore and Trench, combined with the proceeds of his Monte Carlo adventure, Wells completed his acquisition of the ship Tycho Brahe. The mountain of other debts probably swallowed up the rest of the funds. On 15 October 1891 he engaged Captain George Samuel Smith to take command of the vessel for a salary of £180 per annum (£18,000) with food and uniform provided. He told Smith he intended to sail to places such as Monte Carlo, Nice, Cannes, Menton and other Mediterranean ports, and promised him an extra 7s (£35) a week when the ship navigated these foreign waters.

Smith – a man about the same age as Wells – was born in the coastal town of Exmouth, Devon. He went to sea at an early age and, in 1869, while still in his mid-twenties, qualified as a ship’s master on sailing vessels. Two years later he earned his ticket to command steam-driven ships. Then he sailed for years on the lucrative South American run, between Liverpool, Brazil, the River Plate, the Caribbean and the eastern ports of the United States. These were the very routes that Tycho Brahe had been built for, and certainly there were few captains with more experience of this kind of vessel than George Smith. By the time he crossed paths with Charles Wells he had undoubtedly been around the world many times.

When he was not sailing on the ocean waves, Captain Smith lived in Redesdale Street, Chelsea, about half a mile from the offices of Vergis, the shipbroker. It is more than likely that the two were acquainted and that Vergis had introduced him to Wells. At first Smith was cautious. It was well known among mariners that passengers were far more troublesome than cargoes, and besides he was not sure quite what to make of Wells. To Smith, who was a man with both feet firmly planted on the ground, the scheme to create a luxury yacht out of an old rust bucket like the Tycho Brahe seemed quite preposterous. He certainly would not have paid as much for her as Wells had. And, as for the intended improvements, only ‘a mug’ would spend £20,000 (£2 million) as Wells proposed to do. But he conceded that she must have been a beautiful ship when new, and that she was seaworthy. And after some deliberation he decided to give it a try.

A few days later, on 22 October, the purchase was completed and the official register of shipping was amended to show Charles Wells as ‘managing owner’. Wells immediately changed the vessel’s name from the obscure Tycho Brahe to Palais Royal – an inspired choice, which perfectly evokes the floating palace that he had in mind.

The new name was fitting for several other reasons, too. The Palais Royal in Paris had been, from 1642 onwards, the king’s official residence: it is situated at the southern end of the Avenue de l’Opéra, where Charles had his offices a decade earlier. Lastly, as Charles almost certainly knew, it had once been renowned as a gambling centre, where games such as roulette were played before being outlawed in France. It was in this very place that the rules were first established for the principal casino games.

The old cargo ship was moved to the Herculaneum Docks beside the River Mersey. Wells found a nearby shipwright, John J. Marks (‘Ship and Anchor Smiths; Shipwrights, wood and iron’), to transform the decrepit old steamer into a pleasure craft of the most lavish kind. As both Marks and Wells were early subscribers to the new telephone system, they could conduct long-distance discussions between London and Liverpool about the progress of work on the ship.

An important task for Marks was to alter the arrangement of the accommodation below decks so as to provide a saloon, as well as opulent cabins for Wells and his travelling companions. But the pièce de résistance would be the ballroom, 50ft long and extending the entire width of the ship, 32ft, with room for fifty or sixty people to be entertained in comfort. An organ, a grand piano and a harmonium would be provided for the delight of the guests, and for Charles to demonstrate his keyboard prowess.

At that time only 4,000 people out of a population of nearly 38 million were privileged enough to own a yacht. With his existing ‘fleet’ of smaller vessels, Charles Wells was already a member of this elite community: but when the conversion had been completed, the Palais Royal would be something quite out of the ordinary. According to Lloyd’s Register of Yachts for 1892 (which lists ‘all yachts the particulars of which are known’) the Palais Royal would be the seventh largest vessel of its kind in the entire world: Charles Wells Esq., of Portland Place, would soon find himself among some extremely distinguished company. After all, he reasoned, if Queen Victoria and the Emperor of Germany could have gigantic luxury yachts, why should he and Jeannette not have one too?

|

Name of Yacht |

Tons |

Owner |

1 |

Mahroussa |

3,359 |

His Highness the Khedive of Egypt |

2 |

Poliarnaia Zvezda |

3,034 |

His Imperial Majesty the Czar of Russia |

3 |

Derjava |

2,753 |

His Imperial Majesty the Czar of Russia |

4 |

Ceylon |

2,360 |

Mr Drury-Lavin (private owner) |

5 |

Victoria & Albert5 |

2,243 |

Her Majesty Queen Victoria |

6 |

Victoria |

1,692 |

Steam Yacht Victoria Ltd. |

7 |

Palais Royal |

1,633 |

Charles Wells C.E. |

8 |

Osborne6 |

1,490 |

Her Majesty Queen Victoria |

9 |

Hohenzollern |

1,439 |

His Imperial Highness, the Emperor of Germany |

While work on the ship proceeded, Wells paid regular visits to Liverpool, staying at the North-Western Hotel, beside Lime Street Station. In many cities the area around the principal rail terminus becomes the red-light district, and Lime Street was no exception. Its reputation for ‘ladies of the night’ had never been more lurid than in the 1890s.7 And whenever Wells turned up at the docks to see how work on his ship was progressing, he was invariably accompanied by young women. He explained their presence to Captain Smith by saying that they were his ‘nieces’ – an assertion which no doubt caused some amusement among the crew of worldly mariners. Smith later said that he saw champagne being drunk, though Charles Wells, who seldom took alcohol, did not have any.

At other times Wells turned up with Jeannette – also described as a ‘niece’, predictably. The crew naturally noticed that when she and Charles spoke together it was always in French. By way of explanation, Wells told them that she was of Swiss nationality, and was from Zurich. In this, as was so often the case, Wells was not quite telling the truth.

______________

1 A casino game played with cards.

2 We return to this question, reassessing all the possibilities in some detail, later in this book.

3 Although such an action would be most unusual today, Wells is known to have done this on at least one occasion, as described below. In an era long before photocopying had been invented, it was common enough for valuable original documents to be sent back and forth via the postal service – which was, incidentally, both quick and secure.

4 Several references have been found to a book or pamphlet purporting to have been written by Wells, under the title How the Bank was Broken, or similar. Presumably, only a tiny number of copies were ever sent out, and it is believed that no specimens have survived. References to a book by Wells appear in Auckland Star (NZ), 9 July 1892 and Truth, 27 October 1892 – ‘he wrote a book with the object of inducing some fool to furnish him with £8,000 [sic, actually £6,000] in order that he might carry on his gambling operations on a larger scale.’ (See also Coborn, p.227.)

5 The royal yacht.

6 The tender to the royal yacht.

7 The old folk song about a Liverpool prostitute, ‘Maggie May’, popular at the time, includes the line, ‘She’ll never walk down Lime Street any more’.