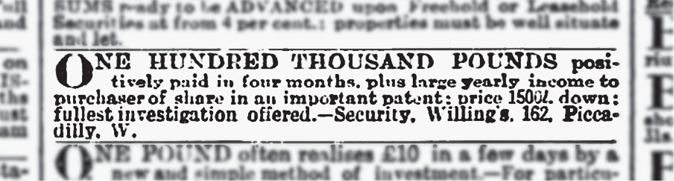

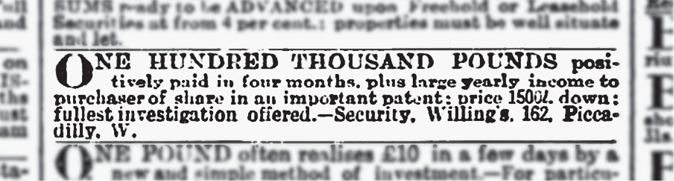

Blake answered this advertisement in The Standard, 16 June 1892.

The fire on board Palais Royal had been a greater setback than Wells cared to admit. Repairing the damage would take a long time, and he found himself once more in serious financial difficulties. Despite this, he put on a brave face and contacted Trench again to say he was going to install new engines in a larger vessel. ‘Now all is right and our harvest is here,’ he wrote. However, the true situation must have been dire because in April he sold the casino shares he had purchased only a few weeks earlier.

Although he had promised Miss Phillimore the enormous sum of £10,000 by mid-March, this sum did not materialise. Instead, using the same tactic he had previously employed with William Trench, he persuaded her to part with a further £1,300: in return he undertook to send £11,000 within a month, plus a £100,000 share in the patent. Miss Phillimore trustingly posted another cheque to him. But instead of cash, Wells sent a bundle of ‘share certificates’, as he called them, in an envelope with a Paris postmark. The shares, he informed her, were in a new company he had formed to promote his inventions – Charles Wells & Co.

Next, he sent a telegram from Menton requesting another £2,000. This time he said he was carrying on important negotiations with the Italian government regarding the sale of an invention. There can be little doubt that he was actually at Monte Carlo and, to cover his tracks, was writing from other nearby towns, Menton being only 12 miles from Monte Carlo. Around the end of April, Wells asked for yet more money, promising a return of £25,000 by the end of the month. For the first time Miss Phillimore appears to have hesitated. However, Wells evidently came up with a convincing response, because in a letter of 9 May she agrees to pay £3,000 into his bank, and virtually apologises for having had misgivings. She emphasises that she has ‘full confidence’ in him, and is ‘sure he would fulfil his promise to pay the £25,000 at the end of May’.

A flurry of letters and telegrams went to and fro until 20 May, when Wells asked for a further £1,200 and promised £150,000 ‘from Russia’. He was now, he said, only short of the ‘miserable amount’ of £500. Although her confidence in Wells was starting to fade again, Miss Phillimore grudgingly paid that sum into his account.

When he did not send any of the money he had promised, Miss Phillimore did what she should have done a long time previously: she consulted her brother, Sir Walter Phillimore, the judge. He advised her to see her solicitor, James Sykes. He, in turn, tried to call on Wells at Great Portland Street. Mr Wells was not in the office, he was told.

On 20 June, a writ was issued against Charles Wells on Miss Phillimore’s behalf, and judgement was obtained for £18,860 (about £2 million). Wells replied three days later to say that he regretted being away at this important time. The attempt to serve him with a summons was ill-conceived, he claimed, because the publicity would be harmful to them both. Soon afterwards he sent another letter in his own handwriting, but on paper headed ‘Wells, Phillimore & Co.’ He addressed her as ‘madam and honoured partner’ and stated that all of the members were liable for any debts of the company, and claimed that if they ruined him they would ruin Miss Phillimore, too, ‘unless she had many millions’. No one could deny that Miss Phillimore had received the shares, he said, and the value of those shares was beyond his control. All shareholders were equally liable, especially ‘founders’. He closed his letter with a jibe at Sykes, the solicitor, claiming that lawyers always tried to make money out of their clients: ‘Very scarce are solicitors who impress upon their clients the wisdom of an arrangement instead of a costly law suit.’ They seemed to think that Wells was a silly fool and that they could get hold of his property. Wells said he knew little about the law, but he had a certain dose of common sense.

For the next part of the intrigue Wells went back to the legal clerk whom he had employed previously – Henry Baker Vaughan. Wells explained that he had won a fortune at Monte Carlo and that he was starting a company in France. He had hinted for some time that he would give Vaughan some kind of administrative role in his affairs, and said the time had come to appoint him company secretary. But Vaughan was not to discuss the matter with Wells’ manager, Hermann Eschen, who might be jealous. Wells offered to take Vaughan on an expenses paid trip to Paris, and promised to give him £1 per day for the duration of the visit. In the event, this was hardly a crippling financial burden for Wells, as they were not gone for more than two days. In fact, the whole expedition seems to have been conducted at whirlwind speed.

On arrival in Paris they first went to the Hôtel Terminus. Wells dashed out on some errand leaving Vaughan on his own, but he returned later and gave him a document to copy. This was an affidavit to say that he, Vaughan, was the company secretary of Wells, Phillimore & Co., which had offices at 16 Rue de Surène. Later, Vaughan asked if he could see these offices and, as they sped through the city in a horse-drawn cab, with an airy wave of his hand Wells pointed out the street where the company was allegedly based. Conversations with various people took place in French, which the bewildered Vaughan did not understand. They drew up outside a building which turned out to be the British Consul’s office, and once inside Vaughan was instructed to swear the affidavit. Caught up in this frenzy of activity he did so, against his better judgement.

On his return to Britain, Wells decided that it was time for the Honourable William Trench to make another contribution. On 13 July, he wrote to the young aristocrat saying that yet another new company – ‘Wells, Phillimore, Trench & Co.’ – had been formed in Paris to exploit the invention, and that the further sum of £1,500 was urgently needed, as otherwise the partners would all be ruined. The company was not limited, he claimed, and therefore the shareholders were fully liable for any debts.

Trench must by now have had his own doubts about Wells. Before handing over the money Trench arranged to meet Wells at Drummond’s – a private bank patronised by the elite of British society, including members of the royal family. This was where Trench’s account was held. Trench insisted that he would only advance more funds if Wells could provide security. Wells offered three of his boats: the small steam launch Flyer, in which Trench had travelled on the Thames, and two yachts, Isabella and Ituna. Apparently satisfied that these assets were good collateral for a loan, Trench then handed over the £1,500 that Wells asked for.

Soon afterwards Wells sent a telegram: ‘Bad news from Paris. Company not being limited all shareholders are responsible.’ In a letter similar to the one he had sent to Miss Phillimore, he wrote:

I must explain what I thought you knew very well. A shareholder is liable to pay up to any extent – even millions, as the company is not limited. Each shareholder is liable to pay the whole. If a shareholder prefers to go bankrupt, then the liabilities fall on any other shareholder. You are a shareholder for the moment. You seem to have taken the matter very coolly, but it is very grave, I assure you.

He ended by saying that Trench must stump up another £10,000 (£1 million) or else they would all be liable for debts of £50,000 (£5 million) in a few days. Finally the truth dawned on Trench. What Wells had told him must be wrong. Although the young aristocrat was inexperienced in these matters, he did not believe that the law could be so unfair, and he consulted his solicitors, Hughes & Gleadow. Trench and Wells went together to the firm’s offices in Gracechurch Street. Wells gave his version of the situation, emphasising that Trench was liable for the company debts, and offering to free him from his obligation in exchange for the sum of £2,500. When quizzed by solicitor Paul Gleadow, Wells said that the company of Wells, Phillimore, Trench & Co. had no books of account and no list of shareholders. Only he, Charles Wells, knew the value of the shares.

At one point Trench lost his temper and threatened to punch Wells, who begged Trench not to hit him, as he was ‘a family man’. He didn’t mind being ‘punched by the law’, he said – with a sly glance at the solicitor, no doubt. He ‘had had encounters of that kind and had come out of them successfully’. The meeting produced no useful result, and Trench and Wells went their separate ways.

Trench next received a notice from Wells inviting him to a company meeting in Paris. Trench’s lawyer, Gleadow, decided to look into the matter further and went to Paris to make enquiries. First he went to 16 Rue de Surène, the supposed offices of Wells, Phillimore, Trench & Co. There was no trace of the company, not even a brass plate at the door. The concierge told him that Wells had once lived in a room there, and had then reserved some office space in the building, but when his furniture was delivered it was of such poor quality that the concierge declined to accept Wells as a tenant.

Paul Gleadow then made his way to the Hôtel Terminus, where the company meeting was due to take place. On reaching Wells’ room he heard women’s voices from within. Wells came to the door. He seemed shocked to see Gleadow and was dumbfounded when the lawyer told him that he had been to the place where the company’s office was supposed to have been. Recovering his poise, Wells said that Gleadow was too late: the meeting had already ended. As Gleadow later recalled:

I asked him where the meeting was held … who attended it, and what was done. He declined to tell me. I said the whole thing was a fraud, that the patent was invalid, and I had the proof – the certificate of abandonment, that is, that the patent had been abandoned. … I said the whole thing was a swindle and a fraud. There was a somewhat heated argument – he said he would have me thrown out of his hotel [and] I then left.

With both Miss Phillimore and the Hon. William Trench firmly out of the picture as far as funding was concerned, Wells was forced to look elsewhere. Reluctantly, he fell back on the old patent scam again and began to advertise. This time the promised rewards were more generous than ever before.

Wells was growing desperate, and it showed. The offer seemed far too good to be true, and only one investor came forward. Frederic Hooper Aldrich-Blake was a young clergyman, not quite 30 years of age, who had graduated from Pembroke College, Cambridge, with a master’s degree. Three years earlier he had been appointed vicar of Bishopswood, near Ross-on-Wye, Herefordshire.

Wells proceeded to give him the usual sales pitch about an improved steam engine with a fuel saving of at least 50 per cent. He said he needed £1,500 to develop it, and undertook to provide a steamboat for demonstrations. As was his custom, he offered Blake a quarter of all profits, and he would retain the rest himself. Wells said he was an experienced engineer, ‘45 years of age’ (he was actually 51), who would not take his clients’ money without being quite sure of the results. He posted his bank passbook to Blake to prove the large sums passing through his hands, and to show himself as ‘a man of position’.

Blake answered this advertisement in The Standard, 16 June 1892.

Blake confessed that he knew nothing whatsoever about steam engines, but offered an investment of £750 – half the amount that Wells said he needed. Wells agreed to this, adding that he guaranteed a return of £50,000, and if this result was not achieved he, Wells, would refund all of Blake’s outlay. On the strength of these representations Blake sent a cheque.

On 25 July Charles Wells filed Patent No. 13,545 of 1892 (under the now predictable heading of ‘steam engines’). The Reverend Blake seems to have been his only ‘catch’ on this occasion, because this was the only patent Wells registered in the whole of that year. In fact, it was the last British patent ever to be recorded in his name.

Blake later met Wells at Great Portland Street, and was introduced to Eschen. Wells assured him that work was proceeding and the machinery would shortly be installed on board a ship at Liverpool. Blake could not help noticing that the office was empty, but Wells explained the absence of any clerks by saying that he had given up his ordinary business for the time being so as to be able to concentrate on the present invention. Blake must have been satisfied by this explanation, as he then gave Wells another cheque for £750, on the promise of another £100,000 which would be paid when the invention was sold.

Wells reported on progress from time to time. Things were going splendidly, he said, and there were good prospects in Germany and Italy. Large sums of money would be on their way to Blake within the month. Wells generously offered to let Blake have his money first as he, Wells, could wait. On 12 September he wrote, ‘Herewith I have the pleasure to send you £3,000’ as the first instalment of the profits. This was only a start, he said. There was just one slight drawback: as before, the payment was in ‘shares’. Wells said he would soon be able to exchange these for cash. And the cash payments would begin at the end of the month, by which time the shares would have doubled or trebled in value. He then asked for a further £500, but Blake declined.

In Liverpool remedial work on the fire-damaged yacht was well advanced. Wells had even engaged a specialist to carry out repairs to the piano – ‘to the tune [!] of £69’, according to one source.

It was time for the yacht to make its first voyage since its reincarnation as Palais Royal. In mid-August Wells came to the docks with Jeannette, and Vergis, his agent, was there to see them off. Wells ordered Captain Smith to make the vessel ready to sail. However, Smith had been growing deeply disillusioned with the job. He had been captain of the ship for ten months and Wells had told him they would be going to Monte Carlo, Nice and other exotic places. Instead he had sat around commanding a vessel which had not so much as moved out of its dock in Liverpool and the only excitement had been when the ship caught fire. It was, he said, ‘too easy a berth’ for him. He had repeatedly asked Wells to sign his contract of employment, but for some reason Wells would not do so, and now his patience was at an end. An argument started between the two men: Smith called Wells a rogue, refused to sail the ship out of Liverpool and, despite Vergis’ attempt to pacify him, quit the appointment.

First Officer Thomas Johnston was now instructed to take command of the vessel. On Saturday, 20 August the Palais Royal sailed majestically down the River Mersey and out to sea, with Wells and Jeannette on board. The newly refurbished vessel must have been a magnificent sight with her eighteen-man crew smartly turned out in their brand new uniforms, which had cost Wells no less than £10 (£1,000) apiece.

The sea was smooth and the winds light as the ship steamed southward along the coast. Next morning they awoke to a fine, very warm day as they rounded the south-western tip of Cornwall, and finally reached Plymouth. Here the vessel was moored in the Great Western Docks, a short distance from Walker Terrace, where Charles Wells had lived with his wife and daughter some seven or eight years earlier.

Wells engaged a prominent local engineering firm, Willoughby Brothers, to finish the alterations, reconstruct the saloon and provide new machinery – a contract worth several thousand pounds, on which numerous men were employed. Wells and Jeannette lived on board while this work was being carried out. He spent much of his time supervising the project, but sometimes he indulged his passion for fishing. At other times he was away for several days on end. One of these trips was to Paris, where he called on a Madame Bichet, who ran a lodging house at 35 Rue de Londres. He took a room there, either to provide himself with a bolthole in France for when things became too hot for him in England, or as a convenient address in France for receiving mail.

Since the Reverend Blake had been so reluctant to part with any more money, Wells resorted to blackmail, adopting the same tactics he had used on Miss Phillimore and Mr Trench. He told Blake that the company was not limited, that all shareholders would be ruined unless Blake paid. He even threatened to contact Blake’s father, a senior churchman. On the other hand, he wrote, the small sum of £1,000 (£100,000) would prevent disaster, and all would be ‘bright and happy forever’. But the clergyman was made of sterner stuff than Wells had realised, and refused to pay. Instead, he returned the shares, and sent a letter to Wells at the Rue de Londres address, informing him that he no longer wanted anything to do with him or his inventions. This letter was subsequently returned via the Dead Letter Office.

Wells had already defended himself successfully in a civil action, when Emily Forrester had taken him to court. But now much more serious criminal proceedings appeared inevitable. If he was arrested, his world would rapidly fall apart. He instantly realised that he must have an escape plan, and that the Palais Royal would play an important part in this. But first the work to the ship needed to be finished, and he was running out of money again.

In a desperate move, on 3 October he borrowed £1,535 (about £150,000) from a finance house in the City of London. In doing so, he surrendered his outright ownership of the vessel, something he was doubtless very reluctant to do. And the fact that he agreed to pay interest at the exorbitant rate of 20 per cent simply underlines the seriousness of his situation. Then, when it seemed that things could get no worse, a new article from Henry Labouchère appeared:

THE BIGGEST SWINDLER LIVING

Readers of Truth are familiar – too familiar, I fear – with the name of ‘C. Wells,’ the fraudulent patent-monger, who carries on business in Great Titchfield Street,1 London, W. For nearly three years past I have been doing my best to warn the public against the machinations of this unscrupulous villain. But there are certain members of the great British public who, unfortunately for themselves do not read Truth, and from among these Wells continues to find victims. Encouraged by the impunity which he enjoys, and the co-operation of some of the leading London papers, he has grown even bolder, and some of his latest coups have been on such a scale that I am quite prepared to find the facts received with incredulity.

The article then goes on to mention – without disclosing their names – a lady who had entrusted Wells with £18,000 (doubtless Miss Phillimore), a gentleman who had invested £10,000 (Trench) and another (unknown) who parted with £4,000–5,000. Labouchère asks, firstly, how it could be that ‘Wells of Monte Carlo’ needs to continue with these frauds if he did in fact win ‘the large sums which he was credited with in sensational telegrams emanating from unknown sources at Monte Carlo’. And, secondly, he asks why Wells has not yet been prosecuted, and urges any of Wells’ other victims to come forward and testify in the interests of justice.

A pivotal moment followed on the morning of 16 November in the High Court of Justice, when a man named Harris, who had invested £240 in one of Wells’ patents, finally brought civil proceedings. Harris claimed repayment of the £240, with an additional £1,000 in damages. Wells had made fraudulent misrepresentations, he claimed, and there had been a breach of contract. It may be that Wells could have avoided a great deal of trouble if he had made an out-of-court settlement. But clearly he did not have the money to do so.

Harris’ counsel described how Wells had obtained funds ‘mostly from widows and unprotected ladies’. There were, he added, ‘a large number of people who had been victims of this heartless swindle’, and he said the public should be made aware of it.

Wells was present in the courtroom, but – once again – took no part in the proceedings. His lawyer tried to argue on his behalf that as the sum of £240 was not disputed, there was no need to go into the alleged fraud.

The judge disagreed. If the allegations were true it was a matter for the criminal courts, and the Public Prosecutor should be informed. The barrister representing Harris left the public in no doubt when he said, ‘I think it should be known that the address of Mr Charles Wells is 154 and 156 Great Portland Street.’

Charles realised that the game was finally up and hurried out of the courtroom. It seems that one or more of his opponents were waiting for him: at any rate, Wells was apparently punched. Nursing a swollen eye, he dashed round to his bank in Sloane Square and withdrew £5,000 from his account, leaving a balance of 5 shillings. Finally, at Paddington Station, he caught the overnight train to Plymouth, where Jeannette anxiously awaited him on board the Palais Royal.

The train drew into Millbay Station just before 5.00 a.m. Charles ‘instructed the cabman to drive with all speed to the yacht, where he told the engineer to get up steam to be away as quickly as possible’ and sail to France. Workmen scrambled to gather their belongings together at such short notice. Some reports suggest that the ship left so abruptly that some of the workers did not even have time to disembark and had to remain on board for the journey. Another, more plausible, version of this story is that Wells had intended to make London his first port of call before proceeding to the Continent. He had at first offered to give two workmen who lived in the capital a lift home. However, as he risked being arrested, he seems to have had second thoughts about the stop in London, and the ship sailed straight to France instead.

Alexander Ferguson, a Scotsman in his early thirties, was second engineer on board. ‘There was a small leak in the boiler at the back of the furnace leading into the combustion chamber,’ he later recalled. ‘Wells said he did not intend to do much to the boilers as he intended to take the fronts out altogether when he got to Marseilles.’ As trivial as the exchange may seem, it demonstrates Wells’ confidence in engineering matters, even when the task ahead was a difficult one. And with remarkable sangfroid for a man on the run, Wells calmly informed Ferguson that he also intended to complete the alterations to the ballroom once they reached Marseille.

The ship stopped at Brest, then went on to Cherbourg, where five of the crew left. ‘We remained in Cherbourg about a week,’ Ferguson said. ‘[Wells] was going to meet a friend, but I do not know that anyone came.’ Ferguson heard some talk of proceeding to Lisbon. This would have been a shrewd move on Wells’ part, as Britain and Portugal did not have reciprocal agreements on extradition. However, the crew’s articles2 would not permit them to go any further than Brest.

‘We could not go to Lisbon,’ Ferguson explained. ‘We were under coasting articles, and if we had gone beyond the coast we should have had the Board of Trade after us, and had no protection from the English Consul.’ Instead, they proceeded eastwards to the port of Le Havre.

A few days later, Detective Inspector Charles Richards went to 154–156 Great Portland Street to search the premises. Just inside the front door stood a large cannon, he noted. In the office upstairs he found a quantity of the headed paper Wells had used for his letters to Miss Phillimore. Printed down one side was a list of the various departments supposedly located at the property, but, on looking around, the officer could see no evidence of the ‘electrical department’, or of the ‘chemical laboratory and testing department’, or ‘machinery in all its branches’ – unless, by some stretch of the imagination, this description extended to the old traction engine, a weighing machine, two pumps and a few lengths of pipe.

What he did find, though, was a large quantity of papers, which he collected together and took away with him as evidence.

It was a dull November day with temperatures hovering just above freezing point when the Palais Royal moored alongside the Quai de la Seine at Le Havre. Charles Deville Wells was so short of ready cash that he made it known in the town that he was prepared to sell 100 tons of coal from the ship’s bunkers. When two smartly dressed gentlemen came marching purposefully along the quayside and boarded the vessel he assumed that they were coal merchants who had come to make an offer. He was mistaken. Britain had applied to France for his extradition. The men were French detectives and brought with them a warrant for his arrest.

The exchange that followed was farcical. The individual who greeted them matched a description of the man wanted by the British authorities: ‘age 50, height 5 feet 4 inches, hair whiskers and moustaches dark (turning grey), very bald, supposed black eye’. There was one discrepancy, though. The fugitive was described as an Englishman, whereas this character insisted that he was French. Indeed, ‘his French was so pure that the detectives were for a moment half inclined to imagine they had got hold of the wrong man’. The ensuing conversation did not exactly clarify matters.

‘Who am I? It’s not my business to find out, it’s yours,’ said Wells.

Charles and Jeannette were placed under arrest and taken to the local jail. The Public Prosecutor ordered his men to search the Palais Royal, and maritime police officers were left to guard the vessel. Under questioning, Wells admitted his true identity, and boasted that he had recently broken the bank at Monte Carlo. At the time of his arrest, though, he had only 24fr. (less than £1) in his pocket.

The story of Wells’ exceptional success at the gaming tables had so far attracted little or no attention in the French press. But the arrest of this mysterious Englishman and his ‘niece’ on a yacht of gargantuan size set the pages of the Paris newspapers ablaze. Motivated more by sensationalism than by any quest for accuracy, Le Figaro claimed, ‘The magnificent English yacht Palais Royal, well known on the shores of the Channel and the Mediterranean, having moored more than once at Nice, arrived yesterday at Le Havre from Cherbourg’.3 According to the article, Wells was ‘one of the richest men in England’. Other dispatches claimed that he had been on the point of leaving for Lisbon, and was only waiting for the tide to turn before doing so. ‘Wells is the man who twice broke the bank at Monte Carlo,’ declared an overexcited columnist. ‘He owns several yachts known as “the Monte Carlo Fleet”.’

The fact that he was accompanied by an attractive woman half his age added spice to the story. ‘Charles Wells, the adventurous man whom Truth has pilloried and assailed with vigour, bids fair to provide us with a romantic titbit for conversation at Christmastide,’ a British journal, the Penny Illustrated, reflected, adding that ‘a young woman who appeared greatly attached to him was found in his company on board the Palais Royal’. Jeannette’s identity remained a mystery until a resourceful journalist probed a little more deeply than his rivals had done, and revealed that ‘she is the daughter of a railway employee from Reims, who recently died’. But this was only part of the story.

Marie Jeanne Pairis was born in 1869 in the Alsace region of France at Mulhouse, an industrial town on the French–German border. Culturally and linguistically, Alsace had always been heavily influenced by its immediate neighbour: most people spoke German as their first language and many had German surnames.

Jeannette – as she was generally known – was the second of eight children born to Georges Constant Pairis and Marie Pairis (née Busch), who had married in 1867 when he was 26 and she was only 16. Georges secured a job with the Eastern Railway of France as a kind of travelling deputy stationmaster. If a local official at one of the smaller stations was indisposed or on leave, Georges was sent there to stand in. The company controlled a railway line extending from Paris to Basel, via Strasbourg, and the family’s life was mapped out between points on this line as Georges was dispatched from one place to another.

All was well until the eve of Jeannette’s first birthday, when the Franco-Prussian War began. The Prussians invaded Alsace and absorbed the region into the German Empire. The invaders had believed at first that the local population would welcome them as liberators, but in reality – despite the people’s strong Germanic roots – very few welcomed the Prussians. Along with some half a million others, the Pairis family became refugees, scrambling and jostling at the railway station and fighting for a place on one of the trains leaving for the unoccupied parts of France. The family settled near the city of Reims, an important railway hub on the Eastern Railway some 80 miles to the north-east of Paris.

A law was passed to the effect that any former inhabitants of Alsace who had migrated in this way could retain their French nationality provided they pledged their allegiance to the country, and undertook not to return to Alsace. In July 1872, 3-year-old Jeannette, her elder sister Léonie and a younger sibling, were taken to the mairie by their parents, who completed the formalities enabling them all to remain French citizens.

By the time Jeannette was 10, her mother was about to give birth to her eighth child. However, some grave complication must have arisen, as the baby lived for only one day and the mother died three weeks afterwards. Jeannette’s father remarried a year later, and it seems that he still preferred younger women, as he was now 40 and his new bride was only 20. This meant that only about ten years separated Jeannette and her stepmother. Friction can often exist between children and a step-parent, but in this case the situation was serious. Georges’ new spouse had eyes for him alone – not for his brood of seven children. And to make things worse, as far as Jeannette was concerned, a new stepbrother and stepsister promptly came along.

All of the children of Georges’ first marriage were then split up and farmed out to various families. The details are unclear, but it is quite likely that Jeannette and her older sister became little more than unpaid servants to their new hosts. Anxious to escape this loveless, Cinderella-like existence, Jeannette eventually made the daunting journey to London on her own – an extremely courageous and possibly dangerous move in those days for a young woman in her teens or early twenties.

While contact with the rest of her brothers and sisters appears to have been sporadic, she seems to have been in regular communication with her elder sister, Léonie. In letters from Britain, Jeannette wrote that she was engaged to an English aristocrat; that he had unexpectedly died just before the wedding; and that his family had rejected her, and left her to fend for herself in a foreign country. The story seemed highly implausible, but it was all Léonie and the others had to go on.

Jeannette was an attractive young woman with remarkable strength of character and a keen sense of adventure. Yet she desperately needed love, stability and material comfort. When Charles Deville Wells came into her life he was able to provide her with these advantages, and a passionate love affair developed between them. There would be times when Charles was on top of the world; and times of great hardship, too. The bond between them survived these extremes of fortune – even though their life together was not always plain sailing.

______________

1 Labouchère overlooks the fact that Wells’ headquarters were now in Great Portland Street.

2 In effect, their contracts of employment.

3 In reality, the only journeys Wells ever made in the ship were from Liverpool to Plymouth and then from Plymouth to Le Havre via Brest and Cherbourg. (Financial Times, 4 April 1893.) Many accounts in books and periodicals describe imaginary voyages with prominent guests being entertained on board. One describes a glittering, but wholly fictitious, dinner attended by ‘five British peers … with their wives, and a German millionaire, three American millionaires and a distinguished French diplomat’. But no doubt this is the sort of thing Charles Wells had in mind when he bought the ship. (Fielding, p.95.)