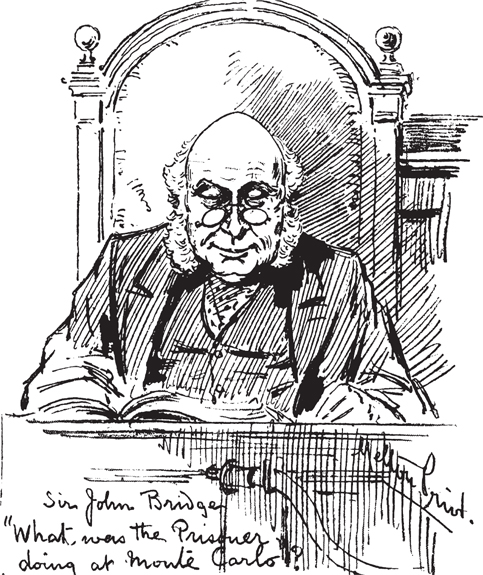

The magistrate, Sir John Bridge.

The arrest of ‘Monte Carlo Wells’ at le Havre was received in Britain with shock, dismay and disbelief. Headlines in the papers such as, ‘SENSATIONAL ARREST FOR FRAUD’ and ‘THE HERO OF MONTE CARLO’ trumpeted the news:

Monte Carlo Wells was for the time the most famous man in Europe. He eclipsed every other social notable. His wealth was supposed to be immense, and everything he touched turned into gold. He became the theme of every music hall and pantomime ditty. No comedy of the day was complete without a reference to the man who broke the bank. … Suddenly there came the crash, and the public learned with pain and surprise that the darling of the hour had been arrested …’ [Author’s italics].

Readers were reminded of Labouchère’s repeated attacks on Wells in the pages of Truth, and there was much conjecture on the outcome of any prosecution, which now seemed inevitable. ‘Perhaps Mr. Charles Wells will emerge triumphant from the web which Mr. Labouchère has been weaving for so long. The man who broke the bank at Monte Carlo ought, at all events, to make a good fight even against so redoubtable an antagonist.’

Wells initially tried to prevent his deportation to Britain by declaring that he was a French subject. However, since he could not possibly substantiate this claim, he later retracted. In his prison cell at Le Havre, he had plenty of time to reflect. At any time someone might discover his crimes in Paris a decade ago, when he had fled the country and been sentenced in his absence. He weighed up the odds, as any gambler would: wait around and serve a two-year prison sentence in France – or stand trial in Britain with a chance of being acquitted. After some thought, he agreed to being handed over to the British authorities without the formalities of a long-winded extradition procedure.

On 9 December, Wells was led into a Le Havre courtroom by two gendarmes. He walked unsteadily and appeared to have suffered a wound to his head. Since arriving in France he had incurred debts, and a Cherbourg businessman had applied for the Palais Royal to be impounded until Wells had settled his bill. A large unpaid invoice from the shipbuilders in England had also caught up with him. Today he was to be examined over these liabilities.

While giving evidence he replied in a faint voice and appeared somewhat confused. In answer to the judge’s questioning, he said he had spent £20,000 on repairs to the Palais Royal. He was rather hazy about the vessel’s present value, however, and also neglected to mention that the ship was already mortgaged in Britain. He told the court:

I recognise the debts contracted by me at Le Havre and Cherbourg, particularly to M. Martin of Cherbourg, but cannot accept the English ship-builder’s invoice. As it is necessary for you to appoint an administrator for my yacht, choose a competent person, because the vessel needs skilled care. In addition, the ship has on board numerous valuable objects, including statues. I insist that an inventory of these goods be made, and a copy given to the captain.

The wound to his head prompted claims that Wells had tried to commit suicide by banging his head against the wall of his cell. However, this rumour was dispelled by a report in Le Temps:

Since his arrest, and contrary to reports, Charles Wells has shown himself to be in good spirits, and, last evening, when officers told him that it had been announced that he had made a suicide attempt he burst out laughing. The owner of the ‘Monte Carlo fleet’ never considered suicide.

It was Jeannette, the newspaper claimed, who had threatened suicide, as she was now left high and dry in France with no funds whatsoever. The Public Prosecutor eventually accepted that she had not participated in any of Wells’ frauds, took pity on her, and gave her the fare back to London.

Shortly afterwards, Wells wrote two letters from his cell. The first was addressed to his agent, Aristides Vergis, asking him to take care of Jeannette. The other was to Jeannette herself, telling her that she could have certain articles at the house in Great Portland Street. He ended by saying, ‘Don’t forget anything. Remember the desk with pigeon-holes.’1

He told reporters that he was sanguine about his return to Britain, and had nothing to fear from the British judges. After all, he said, he just owed some debts, which he would easily be able to repay at some convenient time in the future.

He was due to be handed over to the British police on 12 December, but the documents from London were not delivered in time for this to take place. Then, on the very next day, a local man turned up at the jail and asked if he might be allowed to see the prisoner in his cell. Of all the ports he could have picked, Wells had made the worst possible choice. The man in question was the sea captain from Le Havre who, almost ten years earlier, had invested in the phoney railway at Berck-sur-Mer. He identified Wells as the man who had absconded with his 15,000fr.

British detectives arrived, meanwhile, expecting to take Wells back with them. But this most recent development forced them to return empty handed. The French authorities debated whether to enforce the prison sentence which had been imposed on ‘Will-Wells’ in his absence years ago.

Christmas came and went, as did New Year. Wells remained in his cell while his fate was decided. France’s statute of limitations extended for ten years from the date of the crime. But although, strictly speaking, this period had not quite elapsed, it was clear that some of the crimes had taken place months earlier, and could not therefore be introduced as evidence. Since a conviction was by no means certain, the French authorities decided not to proceed. Besides, the prisoner was proving to be a nuisance and they were finally ‘only too glad to get rid of Wells’.

Appallingly bad weather marked the beginning of 1893. In Paris the thermometer fell to 6 degrees below freezing and the River Seine froze. Snow fell all over northern France. Life in a prison cell is not conducive to the health of a bronchitis sufferer like Charles Wells at the best of times, and the intense cold and damp, combined with the grey skies, must have added to his misery.

Palais Royal was moved to an immense dock close to the town centre, the Bassin du Commerce, where it was moored near the Velléda. This was a boat owned by Henri Menier, a great sailing enthusiast and heir to a renowned chocolate manufacturer. A press report declared that Velléda, one of the most beautiful – and largest – of all French yachts, looked small beside Wells’ ship. The Palais Royal would probably be sold at Le Havre, but it was recognised that its immense proportions might make it an unattractive proposition for ordinary yachtsmen. To make it a little more appealing, all of the furniture and fittings were stripped out to be sold separately.

Wells’ dreams were crumbling and he was powerless to prevent it. To add to his problems, a bankruptcy petition was served on him while he was in the prison. The tailor who had made his crew’s new uniforms, a man named Jupp, had still not been paid for them, and could no longer afford to wait for his money. This action had an immediate and devastating effect on Wells: with a pending bankruptcy he could no longer borrow money to cover his needs, or even access any funds of his own.

On Saturday, 14 January, two British detectives disembarked at Le Havre for a second time with twenty-four warrants from the Bow Street Court. They planned to take Wells back with them on that evening’s ferry, but Wells was said to be ‘seriously ill’ with bronchitis, and their departure was delayed another two days. Finally, French police took Wells to the harbour, and handed him over to detectives Dinnie and McCarthy of Scotland Yard, along with a large bundle of papers which had been found on Palais Royal. After they had boarded the steamer, Dinnie formally read out to Wells the twenty-four warrants – some for fraud, some for theft.

Wells was shaken. ‘I knew of the cases of fraud,’ he replied, ‘but not the larcenies.’2

The overnight ferry Wolf left Le Havre around 10.00 that evening with Wells and the two detectives. The ship ‘had nothing about it in terms of elegance or comfort to remind him of his beautiful yacht the Palais Royal, currently surrounded by ice in the Bassin du Commerce’. As they pulled away from the quayside, it is just possible that Wells may have glimpsed the very top of his yacht’s masts above the rooftops of the town. If so, it was the last time he ever laid eyes on his beloved ship.

Wolf had made this same journey countless times, but after thirty years of service she was nearing the end of her days. Her antiquated engines battled against violent winds and massive waves. Inspector Walter Dinnie, Detective McCarthy, and Charles Wells settled down to the long overnight crossing. Dinnie and Wells were ill-matched travelling companions: both were sons of poets, but they had nothing else in common.

Dinnie was almost ten years younger than Wells, having been born in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, on Boxing Day, 1850. His eldest brother, Donald, a renowned gymnast, was variously described as the ‘greatest athlete in the world’ and ‘the world’s strongest man’. Walter was also a keen sportsman, though he never matched his brother’s prowess in that sphere. Instead he joined the Metropolitan Police in 1876 and became an inspector in 1889. He was a hardworking, straight-laced egotist, who did everything by the book and took an exceptionally dim view of gambling. Quite what he made of Wells, the bank-breaker of Monte Carlo, we can but guess. Nevertheless, Wells was reported as being ‘lively and talkative’ during the voyage. Polite as ever, he thanked the detectives for allowing him time to recover from his illness before making the journey.

Finally, the ferry reached Southampton at 8.00 a.m., over an hour late. The detectives had to help Wells walk from the quayside to their reserved second-class compartment on the train. Detective Inspector Richards – the officer who had searched the Great Portland Street building – met them at Waterloo Station and they all went by cab straight to Bow Street Magistrates’ Court where, again, officers helped him to alight. A little crowd had gathered outside, but no one seemed to recognise ‘the Monte Carlo Hero’, as some newspapers still called him.

This comes as no surprise. If they were expecting to see the debonair young blade described in the music hall song they would have been disappointed. Wells was dressed in a shabby blue overcoat, so long that it reached his ankles. He wore a soft Alpine hat, pulled down over his eyes so that his face was hardly visible. He looked extremely ill and dishevelled. In the words of one onlooker, he was of ‘somewhat common-place appearance, apparently rather over middle age, somewhat under average height … somewhat stout …’

He was somewhat unkempt in appearance, his linen being stained, and his clothes having none of that exquisite fit with which the Wells of a more prosperous period was associated. He looked ill and miserable [and] walked lamely …

A few weeks in a French jail, followed by a return to the cold, damp, smoke-filled air of London had aggravated his chest condition and his cough was ‘quite painful to listen to’.

The mysterious wound to his head was clearly visible and prompted much speculation. In France he may have scoffed at the suggestion that he had attempted suicide, but now an even more implausible explanation was offered by the press. While on Palais Royal, they claimed, ‘he was firing a cannon on board,3 which, being overcharged, recoiled in an unexpected manner and grazed his forehead. Had he received the full force of the blow he would certainly not have lived …’

At this preliminary hearing in the magistrates’ court, the task of the prosecution was to present a sample of the evidence against Wells. Then, if the magistrate determined that the case was sufficiently strong, Wells would stand trial in the Central Criminal Court. If not, he would walk away a free man.

Charles was led into the dock, clutching his hat and avoiding the inquisitive glances directed towards him. At first he looked depressed and downcast, as if he had no fight left in him. Sir John Bridge, Chief Magistrate for London, read out the charges and named some of the alleged victims. As he did so, Wells slowly regained his usual poise. ‘His confidence returned and his demeanour changed to one of apparent bravado. As the charges were read out he appeared unconcerned.’

Sir John asked him whether he was represented in court by a lawyer. When Wells replied to say he was not sure whether his representative was in court, it was the first time the public had heard him speak. ‘It was curious to note that the prisoner’s Continental sojourning had lent him quite a foreign accent.’ Those present in the courtroom also noticed his unusual mannerisms, which included a typically French shrug of the shoulders.

After formal evidence of the arrest had been given by Inspector Dinnie, the hearing was adjourned so that the other witnesses – who were said to be ‘all over England’ – could be rounded up, and to give Wells time to recover from his illness.

A brief but dramatic incident marked the resumption of the hearing eight days later. Seated on the bench was Catherine Mary Phillimore. Beside her sat her brother, Sir Walter Phillimore, the eminent judge. It had been almost exactly four years since she had first answered Wells’ newspaper advertisement. Four years, in which time she had handed over to him the equivalent in today’s money of about £2 million. And the only time they had even come close to meeting in person was when she had become concerned about her money and made the trip to Great Portland Street. This was the occasion when Eschen, the manager, had informed her that his boss was not there, and would not let her in.

Now, in the confines of the crowded courtroom, Miss Phillimore and Charles Wells exchanged glances for the very first time. It must have been a heart stopping moment for them both. A second or two passed as if in slow motion. And then it was back to reality as the hearing began in earnest. Prosecuting counsel Charles Frederick Gill, a barrister of twenty years’ experience, outlined the substance of the case. Since 1888, Charles Wells had done ‘absolutely nothing but defraud people’, he declared. Wells had pretended that his business was established in 1868, and had called himself a civil engineer; he had even put the letters CE after his name but he was not entitled to do so, Gill alleged, as he was not a member of the Institute of Civil Engineers.

However, in reality Wells had become a self-employed engineer in France around 1868. And furthermore, he was considered to be an ingénieur civil in France, as previously mentioned. Besides, there were many people in Britain who claimed to be civil engineers without being members of the Institute of Civil Engineers.4 All of these points should have been challenged by the defence barrister later, but were not.

Gill went on to say that Wells had gone through the motions of patenting everything imaginable – including electric baths.

Sir John Bridge peered over the top of his pince-nez. ‘There was a musical skipping-rope, was there not,’ he enquired.

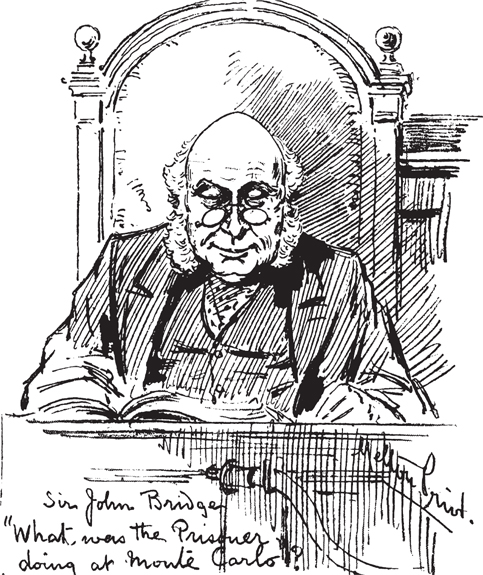

The magistrate, Sir John Bridge.

’Yes, Sir John – and that was the only patent on which he proceeded so far as to get a patent.5 The prisoner applied for such things as navigable balloons, sunshades and foghorns ... signalling fires … bows and arrows, and spring guns.’ Gill accused Wells of having used the huge sums of money he had obtained in this way ‘for gambling’.

Wells was represented by 34-year-old Edward Abinger, who had been a barrister for about five years, and was renowned for the distinctive habit of tapping his snuffbox as he was putting a searching question to a witness, or submitting a difficult argument to a judge.

Miss Phillimore was sworn in and began to tell her side of the story. Looking younger than her 45 years, and clad ‘in deep mourning’ (her mother having died only twelve months previously), she soon won the sympathy of the onlookers. Though nervous, she gave a long and detailed account of her dealings with Wells: the many letters and telegrams, the increasingly urgent requests for more funds, the ever larger cheques. Wells had never sent her a penny of the promised returns, she told the court.

Abinger, with snuffbox at the ready, pointed out that although Miss Phillimore had not received cash, Wells had sent her a parcel of shares instead.

‘They are pieces of paper,’ the magistrate snorted. ‘To call them shares is nonsense.’

‘They are for a larger amount than the capital of the company,’ Gill added, which raised a laugh in the courtroom.

The Honourable William Cosby Trench entered the witness box next. Contemporary accounts portray him as a ‘gentleman of youthful appearance’ with considerably more money than sense. In his testimony he admitted that he had answered no fewer than four separate advertisements, all placed by the same person – Wells. Although the notices all looked remarkably similar, it had simply never occurred to him that they all emanated from the same source. And, every time he responded, Wells offered him a fresh ‘business opportunity’. Then, after Wells had sent him what purported to be the ‘official certificate of patent’, Trench failed to notice that it was only a receipt. This comment met with another outburst of laughter. (But, as we have seen, Trench was certainly not the only one who failed to notice this crucial point. In fact, there is no evidence that any of Wells’ victims realised that the ‘patent certificate’ was no more than an acknowledgement for the application.)

Trench recalled his meeting with Charles Wells at Drummond’s Bank, when he advanced the sum of £1,500 against the security of three of Wells’ yachts. When Wells had failed to repay the money, Trench had taken possession of the boats. However, when they were auctioned off to settle the debt, the amount realised was only a fraction of what Trench had handed over. Between them, the Isabella and the Ituna raised only £90, while Flyer was nowhere to be found.

‘It flew away!’ Sir John Bridge said with glee. ‘Had you no one to whom you could go for advice?’

‘I did not ask anyone.’

‘How old are you?’

‘Twenty-four.’ Trench had no experience of London, and said that the people in the south of Ireland were all honest. He admitted, too, that he had not received a college education. He had seen the enticing advertisements but did not think the profits would be nearly as great as forecast. In fact he had said as much to Wells himself.

As it was now late, the magistrate asked whether the prisoner had any objection to the hearing being continued next day.

‘Please yourself,’ Wells replied nonchalantly, ‘I don’t mind.’ And he was taken back to the cells.

When the next session began, however, Wells was in a despondent mood again. His lawyer was late and missed the start of the proceedings. Sir John asked Wells whether he was represented. He was not, he answered. He didn’t think it was any use being represented after what had happened on the previous day. He would take some notes himself, he said.

A few days later, when Wells appeared in court for a fifth time, it was reported that he had ‘considerably improved in appearance during his incarceration. He now looked in good health and spirits, and watched the case with interest and occasional amusement.’

A woman in her seventies, Caroline Eliza Davison from Paddington, testified that in 1889 she had agreed to invest £100 in a fuel-saving device invented by Wells. She called on him repeatedly to check on progress, and on each occasion he made excuses, blaming the delay on both the Patent Office and the ironworkers who were making the parts. On one occasion he offered her a £50 note and had the gall to say that she could keep it if she would write a glowing reference for him to give to another prospect. She naturally declined to do so, and put the banknote down on the table. Wells snatched it back in the blink of an eye and replaced it in his pocket. Laughter again echoed around the courtroom. Mrs Davison added that she had subsequently sued Wells, but the case had been thrown out on the grounds that the evidence against him was not strong enough.

George Samuel Smith, former captain of the Palais Royal, appeared next. After Smith’s falling out with Wells the prosecution very likely expected his evidence to help clinch the case. He described how the ship had been converted by constructing a saloon, a ballroom and a ladies’ cabin. The ladies in question were described as Wells’ nieces, he added.

‘I don’t suppose there were any uncles?’ Sir John enquired, raising a further laugh. But it is safe to assume that Jeannette – who was in court that day – failed to see the funny side of this particular exchange. As the prosecutors had hoped, Captain Smith’s account of a bevy of young females strengthened their case considerably. It would suggest that Wells’ alleged businesses were actually nothing more than schemes to raise money which he subsequently squandered with abandon.

But then Second Engineer Ferguson was sworn in. He had joined the ship shortly before she sailed from Liverpool to Plymouth, he explained. He recalled Wells coming aboard with Jeannette. In contrast with the captain’s version of events, Ferguson said that he had only ever seen one woman on board, and that he recognised her in court today.

It was clear that Captain Smith had fallen out with Wells. Could Smith’s word be relied on? Perhaps the living was not so riotous after all. And Ferguson’s replies under cross-examination did more good than harm to Wells’ case. He was ‘a very plain-living man,’ Ferguson declared, ‘in fact he lived more plainly than we did.’ If this was the best the prosecution could deliver there was a chance that Wells might be acquitted. But Wells did not have it all his own way. His insistence that the Palais Royal had been bought and fitted out with the sole purpose of demonstrating an improved steam engine was seriously undermined when both Captain Smith and Ferguson testified that the ship’s engines were very old. Neither man had seen any alteration being made for the purpose of saving fuel, or heard of any such plan.

The preliminary hearings at Bow Street dragged on into March, by which time Wells was beginning to look ill and worried again. Miss Frances Budd was the last of his ‘clients’ to give evidence at this stage, and she explained how she had, with difficulty, raised £30 to invest in the small motor for coffee grinders and other household machines. As he had done with other backers, Wells had referred her to his patent agents, Phillips & Leigh, who had told her that he conducted his business with them in an honourable manner. But time passed and she received nothing for her money. She had accused him of being a swindler and would have sued him there and then, she told the court, but friends had advised her that it was not worthwhile.

By an extraordinary coincidence, she later visited Monte Carlo and was taken aback to see none other than Charles Wells at the casino.

‘What was he doing?’ Sir John Bridge enquired.

‘Gambling,’ Miss Budd replied.

‘Breaking the bank, Sir John,’ interjected Wells’ defence lawyer. [Laughter.] The magistrate pointed at Wells. ‘Is that the man you saw playing at the table?’

‘Yes.’

‘Did you follow his luck and get your £30 back?’ Abinger asked.

‘Well, I watched him playing trente et quarante for about half an hour, but I didn’t play.’

Sir John Bridge said that after hearing all the testimony and legal arguments he found evidence of false pretences in all of the cases. He then formally committed Wells for trial.

______________

1 The precise contents of this desk were never revealed, but one item it almost certainly contained was the key to Wells’ safe deposit box in Chancery Lane. This key never was found. As bailiffs were in attendance at the same time as Richards was conducting his search, it is quite possible that they had already removed the desk and its contents. Wells had probably intended to go to Great Portland Street to remove any incriminating items, but – as mentioned above – he evidently decided against returning to his London office and running the risk of being apprehended. (Bankruptcy, 1893, opening remarks (probably read out from Wells’ own statement of affairs).)

2 Larceny (theft) carried a maximum sentence of fourteen years, and was usually easier to prove than fraud.

3 Perhaps the twin of the weapon found by Inspector Richards at Wells’ London premises.

4 The list of civil engineers in the 1892 Kelly’s Post Office Directory – which, incidentally, includes Wells – clearly shows which of these persons belong to the Institute of Civil Engineers. About one-third of those describing themselves as civil engineers do not belong to the Institute.

5 This statement was also wrong, and should have been rebutted by the defence. Twenty-eight patents had in fact been completed.