5: Teaching Them How to Work

If you want the children in your home to work, you will have to teach them. Sorry to say, they probably will not learn to work simply by example. You will have to show and tell, inspect and praise, and it isn’t something that is accomplished in a day. But it can be tremendous fun to see a child’s progress because it is so measurable. Children are usually capable of doing much more than is asked of them. We have a tendency to treat our own children as being two years younger than other adults treat them. There are breakdowns in getting kids to work, and many times it is because we have missed teaching a step in the job process. This is a chapter to be reread when having difficulty. How well children learn to work depends on five things. We will discuss the first four in this chapter.

LEARNING DEPENDS ON

1) The child’s learning style

2) Work techniques

3) Teaching methods

4) Supervision

5) Incentives and consequences

LEARNING STYLES

Does your child work best alone or with others? Is she a reader or a listener? Is he influenced more by peers or by family? Each child learns differently, taking in messages from the world in a unique combination of ways. Research has helped educators identify numerous distinct learning preferences in people. They know that some students do well in traditional classrooms while others do best in open living areas with more freedom. At home you can also identify some of your child’s preferred ways of gathering information by asking the following questions. Their answers will reveal whether their style is to do things alone, with others, or with family members; whether directions are clearer for them when heard rather than seen in print; and whether they like detailed step-by-step instruction rather than a freer atmosphere, where they discover the best way to do something with limited guidance.

“Would you rather work by yourself, with a friend, or with Mom or Dad?”

Style: Individual, Group, or Family

“Should we use a chart to show your responsibilities, or can I just tell you what you should do?”

Style: Reader or Listener

“Do you want me to explain carefully how to wash the car or would you rather read and follow the directions on the can of car wash yourself?”

Style: Detailed Instruction or Discovery

Most children have several preferred styles; a strong identification with only one method is rare. Keep in mind that the younger child tends to be more family oriented than the older child. Some children may just like to work with others more than alone, whether they be family members or peers. Consider the example of Erica, an eight-year-old, who spends every free minute with her nose in a book. Her mother’s words seem to go in one ear and out the other. Erica’s style is the written word. A note that lists her job assignments will have more impact than will constantly telling her what must be done. In the same family, John likes to talk, and to listen intently as his father reads to him. John can be told what needs to be done and does it—he is a listener! Some children like to work with a group of people. For them a “family clean-up hour” will produce more help than an assignment to work alone. Other children enjoy private time and do an excellent job working independently.

The incentives and teaching techniques you use with your children can be structured to fit their individual learning styles. If Tom is influenced by friends more than family, use incentives to encourage better work habits that reward with privileges, like having a friend spend the night, or going to a movie with several friends. The younger child can be motivated by the promise of playing a game with Mom or Dad after work is finished.

Watch and listen to your children for clues of their particular learning preferences, fitting the job method to that style—it could make a difference in how easily they learn and how willingly they cooperate.

SHOW AND TELL STEP-BY-STEP

Let us suppose we are going to teach a five-year-old boy how to clean the bathroom. We need to be conscious of:

1. Breaking the job down into learnable parts

2. Teaching the proper method

3. The physical arrangement of the equipment and supplies

We won’t give him responsibility for the whole room. Let’s try three tasks: scouring the sink, polishing the chrome, and shaking the rug. In thinking of the supplies; is the cleanser where he can get it? What do you want him to use, a cloth or a sponge? (Hopefully not the face cloth.) Is it where he can get to it? Can he reach the sink? Maybe a step stool is needed. When it comes to teaching the proper method, you will give instructions about how much cleanser to use, and mention getting the scum around the drain and not putting the cleanser on the chrome handles. When he shakes the rug, teach him to roll it up and carefully carry it outside so that the bits of dirt don’t fall off on the way. In the beginning, new training takes lots of show and tell. Go with the child every day as he cleans the bathroom, gradually decreasing your physical help but continuing the encouragement until he has mastered it at least three times by himself. Encouragement and positive comments need to be made often at this stage. “It does look better when that brown stuff around the drain is gone.” “The handle shines so nicely, you can even see yourself in it.” You are involving not only the child’s physical senses in the job, but emotions as well. In this case, good emotions are shaping work attitudes: “It looks so nice, I can do it, and I like it better this way.” When this child gets older, such time and detail aren’t needed and you can rely more on verbal instructions. But remember, even as an adult, it is easier to cook crepes for the first time after you have seen someone else cook them. (Psychologists call this modeling.)

Break the job down into manageable parts. You can’t just tell a child to go do the laundry without teaching him how. He has to know how to sort the clothes, operate the washer, select a proper drying procedure, fold, and so forth. Each of these categories can be divided into smaller parts. For the child, concepts are easier to remember than rote details. For example, when trying to teach sorting the soiled laundry, you might talk about dividing according to color, soil, and type of fabric, but also include association concepts like: “This skirt is made out of the same fabric as your jeans so we will put it in with the denims, but will we put it with Brother’s jeans or Dad’s greasy coveralls?” Teach them to analyze for themselves. It might help to post a chart in the laundry area as a quick reference for the correct procedure. Clarify instructions and watch out for double meanings.

Children aren’t the only ones who get themselves into bigger messes than they can clean up. Has the kitchen ever been so littered that you didn’t know where to start? Did you wish there was someone to help? Sometimes we have trouble knowing where to start because everything seems to have something else as a prerequisite—you can’t start washing the dishes until there is a place to put the clean ones. Such an elephant needs to be divided into smaller parts so it can be accomplished. Put away the clean dishes that are in the drainer or dishwasher. Empty the sink. Fill it with hot soapy water. Put all the silverware in the sink and wash that much. Dry that much. Fill the sink with dishes again. Clean off a two-foot square on the counter, and so forth. Here again, a chart above the kitchen sink explaining these small steps may be helpful. Even as an adult, Bonnie finds she cannot force herself to deep clean the kitchen all at once. She takes one little section a day—one cupboard or the refrigerator today, the stove tomorrow. Although doing the whole job is not beyond her physical limitations, she can’t cope with it mentally. But after a week of doing one section each day, she says to herself, “Why, I almost have this kitchen done. I bet I can finish it today.” These are techniques for dividing work into small, manageable areas. Krista, a well-loved baby-sitter, gets the children to pick up toys and clothes by color grouping, a little bit of the Mary Poppins theory: “Let’s pick up everything red.”

We all hesitate to enter a tunnel when we can’t see the end, for fear of not getting out. Weeding the garden could sound like a long tunnel, but dividing it up into four-foot-square sections with a rope or just requiring one row to be done a day isn’t as overwhelming. Rather than saying “Let’s pick up the house,” declare a twenty-pick-up (each person picks up and puts away twenty items), or a five-minute pick-up, offering a foreseeable end. Keep in mind that, after the job is done, giving them another task squelches the incentive to get the first one finished. “Why hurry? If I get this row of beans weeded, Dad will just make me do another one.” Telling them where the end is helps them look beyond this task to freedom.

Give notice of upcoming work periods, keeping them short and successful. At most elementary schools, a warning bell rings five minutes before the final bell, which signals the beginning of school. Advance warning of pending work helps secure cooperation. A standard routine such as morning chores before school or play or evening chores at five o’clock have built-in advance notice. This saves what the kids call unfair surprises. Other early warnings could be for extra work days: “Saturday we’ll work in the yard until noon.” Issuing a five-or ten-minute warning before dinner is ready or play time is over contributes to the general feeling of fairness in a family.

How can we motivate the procrastinator? Try a lead-in activity to start a project or to get in the mood. Ask, “What are you willing to do to this room?” Sometimes just working on it for fifteen minutes can get the child over the hang-up. Reinforcing it with a preferred activity often helps the child get into a project he is hesitant to do. Work before fun. Going to the library and swimming don’t have the same appeal to all children. Take an inventory of what your child likes to do so you’ll know natural interests, learning styles, and possible incentives. For the younger child, a typical preferred activity is a bedtime story. The parent might tell the child that when he is ready for bed, with pajamas on and teeth brushed, he will read the story. To get a little more mileage out of the incentive, the parent could set a timer and say, “If you are ready for bed in ten minutes, I will read a story.” There is a point, however, when the incentive is overshadowed by an overwhelming job. It may be expecting too much to say, “When everything in your room is put away, I will read a story.” Sometimes the technique of giving a negative reinforcement or mildly unpleasant punishment will work. “No TV until your clothes are put away” is a negative reinforcer. Give the child a choice and then provide an escape from the discipline when the child performs the task.

Consider the physical arrangement, equipment, and supplies—make it easy for them to succeed. Guests at the McCullough home have a hard time finding a cup for drinking because they are stored below the counter where the children can put them away when emptying the dishwasher or get them out to set the table, all without parental help. Make it as easy as possible for the child to do for himself. Is there a hook on which to hang his coat? Is his bed the kind he can make by himself? (Bunk beds and double beds are hard for children to make.) Also consider whether there are too many items in the area for the child’s managing capabilities. Maybe a smaller broom would be better for sweeping.

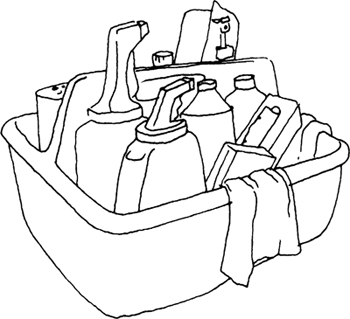

Organize a maid basket in which to keep the basic cleaning supplies: glass cleaner, general cleaner, disinfectant, rags, and paper towels. Having the child take the maid basket with him to clean will encourage a more thorough job. Caution: Keep unsafe supplies elsewhere. Be sure to establish a safe storage location for such supplies, where smaller children cannot get to them. Don’t be afraid to label shelves to show where things go. Trace the outline of the scissors or hammer with a felt-tip marker to show where it belongs. Write out instructions where helpful. Leave notes here and there: “Please rinse out the sink after brushing teeth.” Look for ways to arrange the physical environment so the child can be successful.

It is interesting how clothes affect attitude, actions, and performance. Being fully dressed is part of having the right atmosphere for working. How people work reflects their feelings about themselves. Have the child get dressed, comb hair, and brush her teeth. Even the type of shoes can make a difference in work attitudes. House slippers hint that you are not fully there to work, but are unconsciously in the mood for lounging—and your work may be slower.

Sherolyn found color coding can be a way of making things easier for her child. A newspaper article told about a mother of quintuplet girls who dressed each baby in the same color every day so she could tell them apart. At first, Sherolyn thought that was unfair; surely the girls would grow up to hate their colors. It was, however, a way to make the girls individuals, not just a group. Sherolyn adapted this idea to her children’s possessions, but not necessarily to the color of their clothes. She assigned each of her three children a color; red, yellow, and blue because they are the primary colors and easy to remember. (Mom has green and Dad has purple.) Then she tagged their clothes in the back with a half-inch square of polyester fabric, sewing the swatches into some items of clothing and attaching them to others with gold safety pins. This makes it easy for any member of the family to fold and sort the laundry. Embroidery thread was used on the toes of socks. That way Mom’s nice white tube socks didn’t end up in her teenage son’s pile. Sherolyn bought plastic cups in these colors for the mug rack in the bathroom, to make getting a drink easy and save filling the dishwasher with fifty glasses every day. She used the same colors when buying things like scrapbooks and toothbrushes. Permanent felt-tip pens were used to mark other things. (These could also be the colors used on the family activity calendar.) All of this helped the children to be individual, have their own, and keep it easy. One more thing. Sherolyn ordered two hundred labels from her local fabric store (about two cents each) that said Elrich Family, to sew in clothing. Before a new pair of gloves or new sweater can be worn the first time, the rule is that it has to have a label, making it easier to keep track of possessions. When the kids got navy-blue down coats, just like everyone else in the school, she sewed a little appliquéd figure on the outside to make them easily identifiable. She did the same thing with stocking caps. Even though the Elrich Family tag was on the inside, an appliqéd frog or flag was on the outside, for first-glance recognition.

Teach proper work methods so progress can be seen. Show the child how to work from the outside to the inside, taking care of the clutter scattered around the room before digging into the closet. Starting with the closet first only makes a double mess. Pick up the biggest things and then the smaller things. The bed is usually the biggest item in a bedroom. When it is cleaned off and made up, the room looks seventy-five percent better. Eric commented, “My room seems so much cleaner, and all I’ve done is made my bed.” (An unmade bed is like a signal: “It’s okay to leave everything out today.”) Work in clockwise direction around the room or from the back of the room to the door so as not to work over an area already cleaned. Learn to pick up before the mess becomes monstrous. Stop life and make time after each play period and just before eating or going to bed to allow time to pick up. If you don’t, how can you expect picking up to be a habit? At first it will take great effort, but it will become second nature.

There will be cleaning methods peculiar to your nature or the physical structure of your home that need to be taught. If the disposal isn’t working, the garbage will be scraped into the wastebasket. Tell your children why you put the lettuce on the lower shelf of the refrigerator (so it won’t freeze), and tell them to put a lid on the leftovers because the frost-free feature pulls all the moisture out of the food and because the food will pick up other flavors. We can’t guarantee your children will follow all of your directions, but if they understand the principle, it is more likely to happen.

Insist on order. We subconsciously judge our homes by the impression we get as we come through the door. A custodian said, “When the restrooms and entrances of a building are clean, you assume the whole building is clean.” We are not so worried about what visitors think as about how the family feels about themselves and their home. Filth is just plain unhealthy. Clutter causes confusion, and wastes time. But a sterile house is also uncomfortable. The goal might be for the home to be tidy most of the time. One man complained that the house was always messy—which it wasn’t. The problem was that he entered the home through the garage and into the laundry room, which was piled high with clothes to be mended and folded, and that was his impression of the whole house.

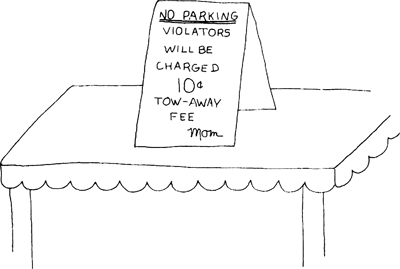

It is important to insist that things not be dropped everywhere and anywhere in the house. In some homes, you can walk in and “read” everything that has happened: The dog won a ribbon for the curliest tail (the certificate is lying on the stereo), a new recipe book arrived (it is on the coffee table), school notices and bills have collected on the kitchen table, and so forth. Make a place for the mail and all the school notices until they can be dealt with. Maybe it will be an in-out file for the mail. The McCulloughs have a “pile-it” corner in the kitchen, (which cannot be easily seen), set aside for “temporary parking” of such items, but they don’t allow every flat surface in the house to become a collecting spot. One mother, who started a campaign against the “drop-it” habit, put up a sign on the table as a reminder of the new emphasis. “No Parking. Violators will be charged 10¢ tow-away fee.”

Many parents complain about children leaving a trail of coats and books behind them as they walk in the house. Create a place to put such items. Install hooks and shelves in a front closet. Then insist that the children use them. Even a box behind a chair for school books is better than books everywhere. Leaving things out in the main living areas gives an illusion of clutter that affects the family morale. A wise man said long ago, “By small and simple things are great things brought to pass.” It may be the control and order of little things that makes a home run smoothly.

Make a time for work. Will your child work in the morning, after dinner, Saturday morning, or Friday afternoon? Having a set time every day or every week will help the child accept the assignment and plan other activities around home responsibilities. To improve cooperation, make this decision together in family council. Contrary to the pleadings of your children, efficiency will improve if friends are not allowed during work time. They will need time, without playmates, to work, and you will need to regulate that work. One mother set the rule that her children would not be available to play with neighborhood friends until noon, to give time for chores, music practice, and quiet play. Another mother preferred nine-to-twelve and three-to-five play periods. A third mother takes a more flexible approach, but says, “no play or TV until chores and bedroom are finished.” Your decision should depend on the children’s ages, interests, the weather, and your schedule. Perhaps you could set up a signal for play time, like the family with a swimming pool, who raised a red flag when it was “free swim.”

HOME MODELS

Make the child believe this job is possible by giving him two types of models: a personal model and a standard for a good job. To offer a human model, be careful when using siblings or friends because resentment might spring up. It is better to use the child himself as a model by referring to past successes. “You did this…, you can probably do this.…” For example, when Eric Monson was struggling with his new paper route in Colorado, his mother pointed out how hard the route had been in Michigan, too, but that it was easier after he had memorized the route. Another time his mother gave encouragement by saying, “You wrote a nice story about Indians. I bet you can write a good one about President Lincoln.” Then she did something about it by taking him to the library. Building on past successes serves as a model for the child, helping him believe it is possible. Mentioning only the good part and not the wrong, the extinction technique, also helps create his own success model because it emphasizes what the child is already doing well. Using the same patience and pleasant comments, pretend your child is the neighbor’s child. It’s interesting how nicely we treat “strangers” but are negative in the familiar atmosphere at home. A positive attitude moves toward something, and a negative attitude moves away from it. A child who is constantly neglecting, forgetting, or procrastinating her chores is moving away from the goals and needs more positive success at the job to serve as her model.

Try using examples and nonexamples. “Four times five equals twenty-one is a nonexample. Giving an example of how it doesn’t work may make the children more aware of the correct process. Using a little furniture polish on the mirror and then comparing the results with the results of using window cleaner may make the point. Most of us at one time or another have confused salt with sugar—a nonexample.

Be sure to discuss improving the method rather than attacking the personality. Avoid bringing in all past mistakes by using such words as always, never, or every time. You could use yourself as a model. Instead of telling the child to put more soap in the dishwater, you could say, “Sometimes I have to add more hot water and soap to get all the grease off the dishes.” The choice is still the child’s. “I find it best to bring all the wastebaskets to the kitchen and empty them into the plastic garbage bag. In case the bag should break, it is easier to clean up.” (This parent is using himself as model and offering “advice.”) If the child chooses another method, fine. He is not defying a parental command, but if the garbage bag breaks on the carpet, guess who gets to clean it up?

A child models best when he has already had a little bit of experience because it puts him in a position to observe and evaluate. If he goes to a friend’s house and helps them wash dishes, he just might observe the advantages and disadvantages of their techniques compared to those used in his own home. The child will begin picking up information from other homes as a baby-sitter or friend, from grandparents, businesses, and at school. A reserve of experiences will be stored on which he can build the satisfying feeling, “I have seen it done; I believe I can do it, too.”

JOB STANDARD MODEL

The second type of model is a standard of acceptable work. How often has a child tried to tell her parent, “But you didn’t tell me that was part of the job,” switching the blame of an incomplete job to the parent. If the adult is very busy or the home has other children, the parent may not be sure if the child is right or not. Try writing a job description for each room or job in your home. When Bonnie did this, it only took about thirty minutes and it helped her decide, in detail, what needed to be done and how often. No matter who was working, whether it was the regular or substitute, they knew exactly what must be done. The job description saves misunderstandings with the children and can help them self-evaluate. It is a measure for parents to use, taking them out of the “bad-guy” spot, and giving the child the responsibility for checking on herself.

Following are the cleaning specifications for the McCullough home. They were typed on index cards and tacked in the closet or behind the curtains of the appropriate rooms. Make your written standard so explicit that a stranger could walk in and understand exactly what should be done.

GUIDED-DISCOVERY QUESTIONING

Guide a child into discovering for himself what still needs to be done by asking questions. “Standing here at the doorway, how does it look?” “Is there something you could do to the drawers to make them look better?” (Close them.) When offering help, leave the responsibility with the child by asking, “Would you like me to help?” But also give him the chance to discover what needs to be done: “What would you like me to do?” Children need to be taught to see disorder and dirt as the adult sees it. “Did you notice…?” However, don’t ask questions that build guilt or demand confessions: “Why is your room such a mess?” How often has a parent gone into a messy bedroom and told the child to put everything away and received the answer “It is put away; that’s where I keep it.” The inspection chart used by the Monsons (as shown here) was a good method for helping their children know what Mom was checking. They were given a copy of the grading chart to inspect for themselves, after Sue had checked it, and they saw their bedrooms in a new way.

CLEANING SPECIFICATIONS

(to be tacked in closets):

Front Room

Daily:

Put away books and toys

Close piano; put bench under

Straighten cushions

Put newspapers neatly under table in far corner

Vacuum traffic areas

Weekly: (Saturday)

Vacuum carpet

Dust all furniture

Take newspapers to garage

Damp-wipe around door

Shake rugs

Sweep porch

Bathroom

Daily:

Pick up all hair equipment and straighten counter

Pick up toys and clothes

Straighten towels

Scour sink and polish chrome

Wipe off back of toilet

Shake rug

Weekly:

Scour toilet bowl

Wash towels

Wash brushes and combs

Polish mirrors

Sweep and mop floor

Bedrooms

Daily:

Make bed

Pick up clothes

Fold and put away pajamas

Keep top of bed and chest neat

Weekly:

Dust

Vacuum

Straighten drawers

Change bed sheets

Damp-wipe around door

Family Room

Daily

Pick up toys and books

Straighten blankets and pillows

Weekly:

Vacuum carpet

Wipe TV and around doors

Dust

Kitchen

Daily:

Rinse and put dishes in dishwasher

Refill cold drinking water

Cover leftovers and put in refrigerator

Wash pans and serving bowls

Dry pans and serving bowls

Shake rugs

Sweep floor

Scour and polish sink

Wipe off counters and table

Put away chairs

Fold down table

One father plays a game with his kids which is patterned after the observation game. The observer gets a minute to look at twenty items on a tray before it is taken away, and then tries to list them all. This father challenges his young children to put away twenty things, and then Dad tries to remember as many of them as he can. This trains the child to notice what is out of place. After a while the child may put away little tiny things to trick Dad, but that’s okay because awareness is developed. It is a way of giving immediate, positive social attention to what has been put away, rather than negative reminders about the items left out. Dad’s attention is such a premium, the kids love it.

As adults, once we have become good at a job, it is hard to realize there could be another way to do it. An optimistic young adult, Joan, went to Israel to live in a communal kibbutz. Even though all the work positions were treated with dignity, Joan said, the individualism was gone. When someone was assigned to clean the dining room floor, there were supervising experts who had been streamlining the job for forty years. They were so efficient that a drain had been installed in the center of the dining room floor. The floor could be hosed down and wiped with a squeegee such as we use on windows. They knew which side of the room to start on and which way to make the strokes. They were so efficient, there was no room for individual interpretation or personal discovery. One woman carries negative memories of her mother picking at her for every little thing, even yelling at her for sweeping dirt away from her with the broom rather than toward her. The daughter preferred the “away” strokes because it kept her shoes from getting dusty. In your home, you have a right to expect a minimum standard, but not to dictate every action. Self-discovery can be a great motivator. “Tell me how you think this would be best done?” It could be taken so far as to ask the child to write down what she thinks would be the best method for cleaning the bathroom, and share them with the family. Parents get in a habit of issuing commands, especially when we are very busy, and forget to let the child do the discovering. To discover an answer or method is better than to be told. The discovered answer is remembered longer because it involves an analytical process in the mind rather than using just the ears. Most questions automatically arouse curiosity. Use them often.

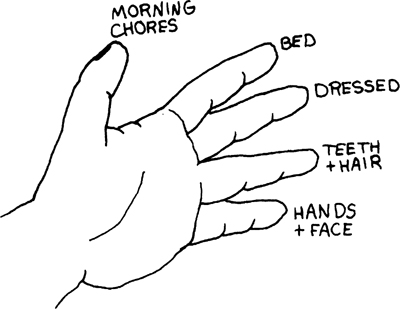

Finger plays for chores. Teach young children to take on their own responsibilities with a simple reminder system on their fingers. Instead of demanding “Is your bed made?” the parent can ask “What do you have left to do this morning?” and the child can answer “I still have to make my bed and brush my teeth.” You have put the responsibility where it belongs. What makes this work? The parent teaches the child a sequence of key words or phrases, one for each finger. Each day, the child runs through the list on his fingers and does each task. When he is finished, he is ready to go to school or play.

To begin this in your home, list the tasks that need to be done every day. Pick a noun as the key word to represent each job. Arrange them in sequential order. Brushing teeth and washing would come before dressing, to prevent splashes on clean clothes. The sequence the McCullough family uses is as follows: (1) hands and face, (2) teeth and hair, (3) dressed (including shoes and socks), (4) bed (including room pick-up), (5) morning chore, or just toys for the youngest children. They don’t include eating breakfast on the list because they don’t have a problem in that area. Use the same set of words for all children in a family. Added responsibility can be attached to the symbol word as the child matures, but don’t try to change the key words. For instance, under the third category, bed, a four-year-old may not be asked to vacuum his bedroom, but by the time he is seven, vacuuming might be part of his responsibility.

When the child needs a reminder, the parent says, “What have you finished so far?” After going over the sequence of words on his fingers, the child will answer, “Well, I’ve swept the stairs and made my bed, but I still have to brush my teeth.” She has been the one to recognize what must be done, and she is on the way to self-rule. This memory device of learning the morning routine on fingers can be started as young as two years or as late as seven years, and will last a lifetime. The most important point is that the child learns to answer the questions “Am I finished yet?” and “What must I still do?”

The McCulloughs started teaching their youngest child personal responsibility at two and a half years. After dressing him, Bonnie takes his hand in hers and points to one finger at a time (like playing piggy-wiggy). “Now, Mattie, let’s see what you have to do. Hands and face?” (He nods yes whether he has done it or not.) “Teeth and hair? No? Let’s do that now.” When he has finished brushing, she begins again. “Dressed? Yes, and your shoes are on too! Good! Bed?” (Nods yes.) “No, I’ll help you. Toys? We’ll pick up your books after we have made the bed.” Taking him by the hand, she leads him patiently through each activity. Naturally, he was too young in the beginning to make his bed, but he stood next to her while she did it. In a year or so, he was climbing up at the head of the bed and Bonnie was tossing the quilts to him. Then he would put the pillow on and cover it up. When they were all finished, Bonnie gave a positive comment and then told him he could play because all his chores were finished. He left feeling grown up and successful. A bonus: Mom had fewer interruptions because all of his immediate needs had been taken care of first.

After the basic hygiene and chores are taken care of, a child is free from parental promptings. He feels rewarded for his accomplishment because he is ready for whatever opportunity comes up. He can go for a ride to the store or play with a friend. Once the basic responsibilities are established, parents can be more than just reminders. They can be leaders instead of herders.

SUPERVISION

If you want to achieve the goal of getting your child to work at home, be available to supervise—not as a taskmaster with a whip but as a coach, to direct, help, encourage, and motivate. It won’t happen if the parent is off in the basement ironing or doing a complicated job while the children (four to ten years) are supposed to be working. On a construction job, organized under a labor union, a supervisor cannot participate in the actual labor. This policy does not apply at home. A little friendly help from the parent now and then fosters a “caring” attitude in the home. Being reachable lets the child know that if he needs assistance, it is available.

When the parent is near the action, expressions of encouragement on how well the job is coming and appreciation when the job is completed are more likely to be given—helping to fill the basic human need for self-esteem. When these verbal rewards are given, the child is more likely to work again for you. The child also wants to know, “Did I do it right?” One neighbor commented that even as a teen she never worked when her mom was gone, even though the hours dragged and there was nothing else to do. She needed adult feedback. Unconsciously, some children feel that even negative chastisement is better than nothing at all. Kids like a little reminding as a signal their parents care. As children get older, they work alone for longer periods of time. There are even a few teens who prefer to get their work done before their parents get home. Part of this is a feeling of grown-up-ness. You will find the logic quite interesting. Teens say they do their chores before their parents get home:

Because it’s easier and I can do them my way

Because we don’t have to do a good job

Because my mom won’t do things that I want if I don’t do my chores

Because I really love them and don’t believe in cheating on work

To surprise them when they get home

Because I don’t like a dirty house

Make sure the child has enough practice at succeeding with a job. The more we do something, the easier it becomes. The first time you make a new recipe, it takes almost twice as long as the second time. There are children who prefer a chore assignment for a week or two because they become efficient at the job.

Should I call a child back to re-do a job? Yes, if there has been a specific rule infraction or the child has tried to slip by with a half-way job. But remember this: If you are always calling your child from play or interrupting an activity, you may one day wonder why your child doesn’t stick to one project for more than a few minutes. One mother found it worked, especially in the summer, to keep a list of things that needed attention and brought it forth at the next work time, giving the children some “free time” between the work sessions.

For some jobs, we not only need the skill, but we have to develop the self-motivation to do it every day—for example, bed making. It not only takes help to learn the skill, it takes parental help, especially supervision, to learn the mature work habit of following through—a principle not usually considered. We assume that because the child has the skill, he can do it. The reason he often can’t, is because he doesn’t have the habit yet. Establishing the habit takes much longer than teaching the skill. Parents can help establish firm habits by offering proper supervision, providing practice, exercising patience, and yes, by dangling carrots—incentives. Proper supervision takes “super vision.”

While you are working together, take time to talk, but don’t lecture. Talk about future plans, what happened at school, an exciting book, anything. This can be a time of communication. Thirty years ago, children spent most of their lives in close, side-by-side working associations with their parents and relatives. This togetherness helped the child model, pick up similar values, and learn to work. In our society today, a child spends less than fourteen minutes a week talking with his parents, which hardly represents competition for television, school, and peers. Take time to talk with, not just talk at, your child. If you run out of things to talk about, try telling jokes or singing together.