2

Finding Your Type

Neuroscientists have determined the brain’s dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is associated with decision making and cost-benefit assessments. If MRI brain scans had been performed on my friends and me one summer’s night when we were fifteen, they would have revealed a dark spot indicating a complete absence of activity in this region of our brains.

That particular Saturday night a group of us got the brilliant idea that streaking a golf banquet at an exclusive country club in my hometown of Greenwich, Connecticut, was a wise decision. Other than certain arrest for indecent exposure, there was only one problem: Greenwich isn’t a big town, and it was likely someone we knew would recognize us. After several minutes of deliberation we decided our friend Mike should run home and return with ski masks for each of us.

And so at roughly 9:00 p.m. on a warm August night, six naked boys in ski masks, several of which were adorned with pom-poms, sprinted like startled gazelles through a beautiful oak-paneled room full of bankers and heiresses. The men clapped and cheered for us while the bejeweled women sat frozen in shock. We had hoped for the opposite reaction, but there was not ample time to stop and express our disappointment.

And that would have been the end of it if it weren’t for my mother. “What did you and the guys do last night?” she asked the next morning as I walked into the kitchen and rummaged through the fridge.

“Not much. We hung out at Mike’s, then crashed around midnight.”

My mother is normally chatty, so I was puzzled when she didn’t ask how my friends were doing or what my plans were for the rest of the day. I instantly had an uneasy feeling.

“What did you and Dad do last night?” I said brightly.

“We went as guests of the Dorfmanns to their club’s golf banquet,” she replied in a tone that was one part sugar, one part steel.

Most people don’t ever anticipate that a sudden change in cabin pressure might occur in their home, triggering the hope that an oxygen mask would fall from somewhere overhead to replace the air that shock has just sucked out of their lungs.

“A ski mask?” she demanded, her voice rising as she strolled toward me like an angry Irish cop patting his truncheon in the palm of his hand. “A ski mask?”

The tip of her nose was no more than an inch from my own. “I could pick your scrawny butt out of a lineup in the dark,” she whispered menacingly.

I tensed, wondering what was coming next, but the storm passed as abruptly as it rolled in. My mother’s face relaxed into a sly grin. She turned on her heels and said over her shoulder as she walked out of the kitchen, “You’re lucky your father thought it was funny.”

This was not the first time I wore a mask to protect myself—far from it.

Human beings are wired for survival. As little kids we instinctually place a mask called personality over parts of our authentic self to protect us from harm and make our way in the world. Made up of innate qualities, coping strategies, conditioned reflexes and defense mechanisms, among lots of other things, our personality helps us know and do what we sense is required to please our parents, to fit in and relate well to our friends, to satisfy the expectations of our culture and to get our basic needs met. Over time our adaptive strategies become increasingly complex. They get triggered so predictably, so often and so automatically that we can’t tell where they end and our true natures begin. Ironically, the term personality is derived from the Greek word for mask ( persona), reflecting our tendency to confuse the masks we wear with our true selves, even long after the threats of early childhood have passed. Now we no longer have a personality; our personality has us! Now, rather than protect our defenseless hearts against the inevitable wounds and losses of childhood, our personalities—which we and others experience as the ways we predictably think, feel, act, react, process information and see the world—limit or imprison us.

Worst of all, by overidentifying who we are with our personality we forget or lose touch with our authentic self—the beautiful essence of who we are. As Frederick Buechner so poignantly describes it, “The original, shimmering self gets buried so deep that most of us end up hardly living out of it at all. Instead we live out all the other selves, which we are constantly putting on and taking off like coats and hats against the world’s weather.”

Though I’m a trained counselor, I don’t know exactly how, when or why this occurs, only that this idea of having lost connection with my true self rings true with my experience. How many times while spying my children play or while gazing up at the moon in a reflective moment have I felt a strange nostalgia for something or someone I lost touch with long ago? Buried in the deepest precincts of being I sense there’s a truer, more luminous expression of myself, and that as long as I remain estranged from it I will never feel fully alive or whole. Maybe you have felt the same.

The good news is we have a God who would know our scrawny butt anywhere. He remembers who we are, the person he knit together in our mother’s womb, and he wants to help restore us to our authentic selves.

Is this the language of the therapeutic under the guise of theology? No. Great Christian thinkers from Augustine to Thomas Merton would agree this is one of the vital spiritual journeys apart from which no Christian can enjoy the wholeness that is their birthright. As Merton put it, “Before we can become who we really are, we must become conscious of the fact that the person who we think we are, here and now, is at best an impostor and a stranger.” Becoming conscious is where the Enneagram comes in.

The goal of understanding your Enneagram “type” or “number”—the terms are used interchangeably in this book—is not to delete and replace your personality with a new one. Not only is this not possible, it would be a bad idea. You need a personality or you won’t get asked to prom. The purpose of the Enneagram is to develop self-knowledge and learn how to recognize and dis-identify with the parts of our personalities that limit us so we can be reunited with our truest and best selves, that “pure diamond, blazing with the invisible light of heaven,” as Thomas Merton said. The point of it is self-understanding and growing beyond the self-defeating dimensions of our personality, as well as improving relationships and growing in compassion for others.

The Nine Personality Types

The Enneagram teaches that there are nine different personality styles in the world, one of which we naturally gravitate toward and adopt in childhood to cope and feel safe. Each type or number has a distinct way of seeing the world and an underlying motivation that powerfully influences how that type thinks, feels and behaves.

If you’re like I was, you will immediately object to the suggestion that there are only nine basic personality types on a planet of more than seven billion people. A single visit to the paint aisle at Home Depot to help an indecisive spouse find “that perfect red” for the bathroom walls might quell your remonstrations. As I recently learned, there are literally an infinite number of variations of the color red from which you can select to brighten your bathroom and wreck your marriage at the same time. In the same way, though we all adopt one (and only one) of these types in childhood, there are an infinite number of expressions of each number, some of which might present in a similar way to yours and many of which will look nothing like you on the exterior—but you are all still variations of the same primary color. So don’t worry, Mom didn’t lie. You are still her special little snowflake.

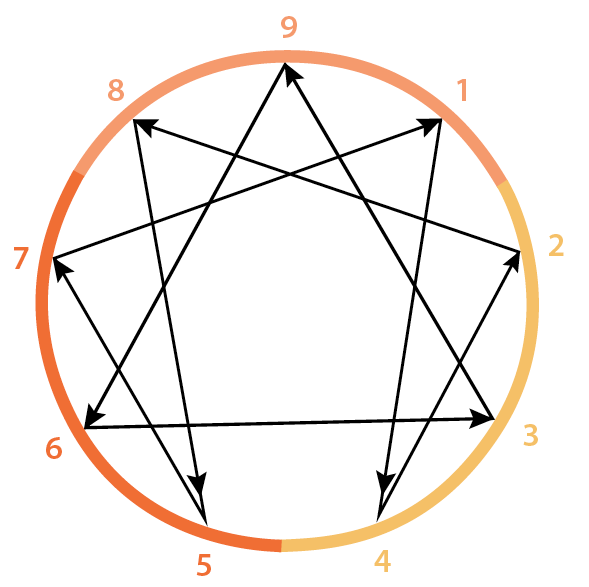

The Enneagram takes its name from the Greek words for nine (ennea) and for a drawing or figure (gram). It is a nine-pointed geometric figure that illustrates nine different but interconnected personality types. Each numbered point on the circumference is connected to two others by arrows across the circle, indicating their dynamic interaction with one another.

If you haven’t already jumped ahead in this book to begin figuring out which number you are, figure 1 is a snapshot of the diagram. I’ve also listed the names and a quick description of each Enneagram number. For the record, no personality type is better or worse than another, each has its own strengths and weaknesses, and none is gender-biased.

Figure 1. The Enneagram diagram

TYPE ONE: The Perfectionist. Ethical, dedicated and reliable, they are motivated by a desire to live the right way, improve the world, and avoid fault and blame.

TYPE TWO: The Helper. Warm, caring and giving, they are motivated by a need to be loved and needed, and to avoid acknowledging their own needs.

TYPE THREE: The Performer. Success-oriented, image-conscious and wired for productivity, they are motivated by a need to be (or appear to be) successful and to avoid failure.

TYPE FOUR: The Romantic. Creative, sensitive and moody, they are motivated by a need to be understood, experience their oversized feelings and avoid being ordinary.

TYPE FIVE: The Investigator. Analytical, detached and private, they are motivated by a need to gain knowledge, conserve energy and avoid relying on others.

TYPE SIX: The Loyalist. Committed, practical and witty, they are worst-case-scenario thinkers who are motivated by fear and the need for security.

TYPE SEVEN: The Enthusiast. Fun, spontaneous and adventurous, they are motivated by a need to be happy, to plan stimulating experiences and to avoid pain.

TYPE EIGHT: The Challenger. Commanding, intense and confrontational, they are motivated by a need to be strong and avoid feeling weak or vulnerable.

TYPE NINE: The Peacemaker. Pleasant, laid back and accommodating, they are motivated by a need to keep the peace, merge with others and avoid conflict.

“A humble self-knowledge is a surer way to God than a search after deep learning.”

Thomas À Kempis

Maybe now you’re starting to get an idea of which of the nine types you belong to (or which one explains your seventy-year-old uncle who still dresses up like Yoda and attends Star Wars conventions). But the Enneagram is more than a piddling list of clever type names, so that’s just the beginning. In the following chapters we’ll learn not only about each number in turn but also about how those numbers relate to others. Don’t be discouraged if the terminology or the diagram, with its lines and arrows ricocheting around, looks confusing. I promise it will make sense to you in short order.

Triads

The nine numbers on the Enneagram are divided into three triads—three in the Heart or Feeling Triad, three in the Head or Fear Triad, and three in the Gut or Anger Triad. Each of the three numbers in each triad is driven in different ways by an emotion related to a part of the body known as a center of intelligence. Basically, your triad is another way of describing how you habitually take in, process and respond to life.

The Anger or Gut Triad (8, 9, 1). These numbers are driven by anger—Eight externalizes it, Nine forgets it, and One internalizes it. They take in and respond to life instinctually or “at the gut level.” They tend to express themselves honestly and directly.

The Feeling or Heart Triad (2, 3, 4). These numbers are driven by feelings—Twos focus outwardly on the feelings of others, Threes have trouble recognizing their own or other people’s feelings, and Fours concentrate their attention inwardly on their own feelings. They each take in and relate to life from their heart and are more image-conscious than other numbers.

The Fear or Head Triad (5, 6, 7). These numbers are driven by fear—Five externalizes it, Six forgets it, and Seven internalizes it. They take in and relate to the world through the mind. They tend to think and plan carefully before they act.

Chapter order. Speaking of triads, if you look at the table of contents you will notice we have chosen not to describe the types in numerical order but to group and discuss them in the context of their respective triads: Eight, Nine and One are together; then Two, Three and Four; and finally Five, Six and Seven. The reason we chose to order the chapters like this is to help you see the important ways in which each number compares to its fellow “triadic roommates.” If anything, this will not only make the Enneagram easier to understand but also aid you in your search for your number.

Wing, Stress and Security Numbers

One of the things I love about the Enneagram is that it recognizes and takes into account the fluid nature of the personality, which is constantly adapting as circumstances change. There are times when it’s in a healthy space, times when it’s in an okay space, or times when it’s downright nuts. The point is, it’s always moving up and down on a spectrum ranging from healthy to average to unhealthy depending on where you are and what’s happening. At the beginning of each chapter I’ll briefly describe in broad terms how each number typically thinks, feels and acts when they’re camped out in a healthy, average and unhealthy space within their type.

Look at the Enneagram diagram and you’ll see that each number has a dynamic relationship with four other numbers. Each number touches the two on either side, as well as the two at the other end of the arrows. These four other numbers can be seen as resources that give you access to their traits or “juice” or “flavor,” as I like to say. While your motivation and number never change, your behavior can be influenced by these other numbers, so much so that you can even look like one of them from time to time. As you’ll see in each chapter, you can learn to move deliberately around the circle, using these for extra support as needed.

Wing numbers. These are the numbers on either side of your number. You may lean toward one of these two wing numbers and pick up some of its characteristic energy and traits. For example, my friend Doran is a Four (the Romantic) with a Three wing (the Performer). He is more outgoing and more inclined to perform for recognition than a Four with a Five wing (the Investigator), who is more introverted and withdrawing.

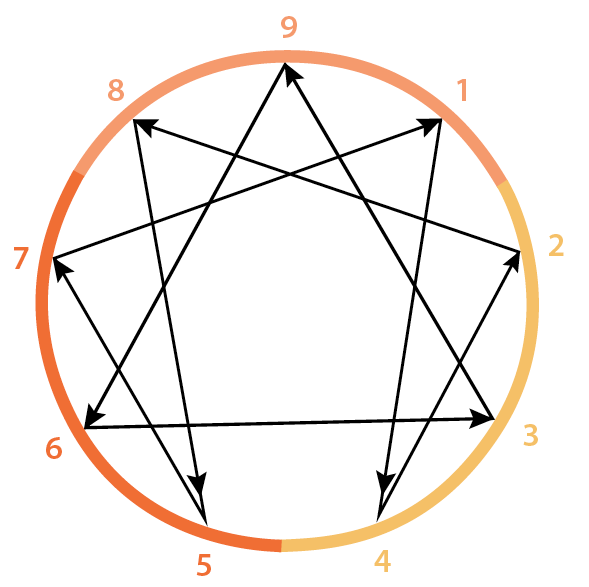

Stress and security numbers. Your stress number is the number your personality moves toward when you are overtaxed, under fire, or in the paint aisle at Home Depot with an equivocating friend or partner. It’s indicated by the arrow pointing away from your number on the Enneagram diagram in figure 2.

Figure 2. Stress and security arrows

For example, normally happy-go-lucky Sevens move toward and take on the negative qualities of the One (the Perfectionist) in stress. They can become less easygoing and adopt more black-and-white thinking. It’s important for you to know the number that you go to in stress so that when you catch it activating you can make better choices and take care of yourself.

Your security number indicates the type your personality moves toward and draws energy and resources from when you’re feeling secure. It is indicated by the arrow pointing toward your number on the Enneagram. For example, Sevens take on the positive qualities of Five when they’re feeling secure. That means they can let go of their need for excess and embrace the notion that less is more.

Spiritually speaking, it’s a real advantage to know what happens to your type and the number it naturally goes to in stress. It’s equally valuable to learn the positive qualities of the number you instinctively move toward in security as well. Once you become familiar with this material you can know and catch yourself when you’re heading in the direction of a breakthrough or a breakdown, and make wiser choices than in the past. There’s a lot to this topic of security and stress, but because this is book is a primer we’ll only cover the basics. Just know there is much more to learn about it.

Discover Your Deadly Sin

It may sound like something from a medieval morality play, but each number has a deadly sin associated with it, and in each chapter Suzanne and I will be diving deeper into what that looks like. For some, the word sin evokes terrible memories and feelings. Sin as a theological term has been weaponized and used against so many people that it’s hard to address the subject without knowing you’re possibly hurting someone who has “stood on the wrong end of the preacher’s barrel,” so to speak. But as a weathered sinner and recovering alcoholic with twenty-eight years of sobriety, I know that not facing the reality of our darkness and its sources is a really, really bad idea. Trust me, if you don’t, it will eventually come out of your paycheck at the end of the month.

“It is my belief no man ever understands quite his own artful dodges to escape from the grim shadow of self-knowledge.”

Joseph Conrad

Bearing sensitivities in mind, allow me to offer a definition of sin I have found helpful and one we might use together in our conversation. Richard Rohr writes, “Sins are fixations that prevent the energy of life, God’s love, from flowing freely. [They are] self-erected blockades that cut us off from God and hence from our own authentic potential.” As someone who goes to a church basement several mornings a week to meet with others who need support to stay away from just one of my many fixations, this definition rings true. We all have our preferred ways of circumventing God to get what we want, and unless we own and face them head-on they will one day turn our lives into nettled messes.

Every Enneagram number has a unique “passion” or deadly sin that drives that number’s behavior. The teachers who developed the Enneagram saw that each of the nine numbers had a particular weakness or temptation to commit one of the Seven Deadly Sins, drawn from the list Pope Gregory composed in the sixth century, plus fear and deceit (along the way a wise person added these two, which is nice because now no one needs to feel left out). Each personality’s deadly sin is like an addictive, involuntarily repeated behavior that we can only be free of when we recognize how often we give it the keys to drive our personality. Again, don’t think the term deadly sin sounds too early Middle Ages to still be relevant. It’s timeless and important wisdom! As long as we are unaware of our deadly sin and the way it lurks around unchallenged in our lives we will remain in bondage to it. Learning to manage your deadly sin rather than allowing it to manage you is one of the goals of the Enneagram.

There are other personality typing systems or inventories like the Myers-Briggs or the Five Factor test that are wonderful but exclusively psychological in orientation. There are others that describe and encourage you to embrace who you are, which isn’t very helpful if who you are is a jerk. Regardless, only one of these instruments addresses the fact that we are spiritually mottled creatures. The Enneagram is not exclusively psychological, nor is it feel-good, self-help pabulum when taught correctly. (By the way, if my “self” could have helped my “self,” don’t you think my “self” would have done it by now?) The true purpose of the Enneagram is to reveal to you your shadow side and offer spiritual counsel on how to open it to the transformative light of grace. Coming face-to-face with your deadly sin can be hard, even painful, because it raises to conscious awareness the nastier bits about who we are that we’d rather not think about. “No one should work with the Enneagram if what they seek is flattery. But no one should fail to do so if what they seek is deep knowing of self,” as David Benner cautions. So, bravely on!

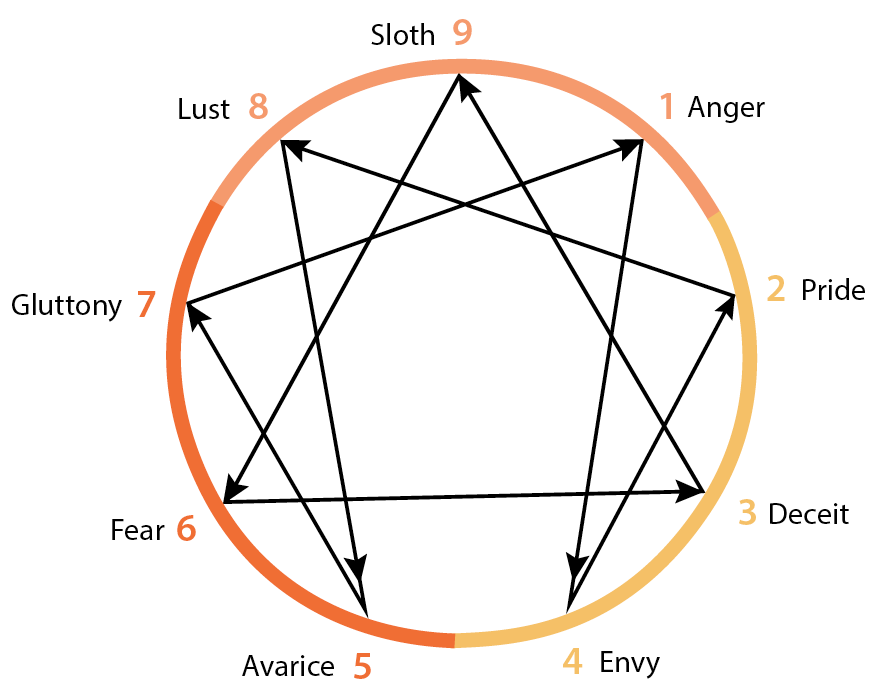

Here’s a list of the Seven Deadly Sins (plus two) and the number to which each correlates, as well as a brief description of them (see figure 3). The descriptions are drawn from Don Riso and Russ Hudson’s The Wisdom of the Enneagram.

Figure 3. Sins correlating to each number

ONES: Anger. Ones feel a compulsive need to perfect the world. Keenly aware that neither they nor anyone else can live up to their impossibly high standards, they experience anger in the form of smoldering resentment.

TWOS: Pride. Twos direct all their attention and energy toward meeting the needs of others while disavowing having any of their own. Their secret belief that they alone know what’s best for others and that they’re indispensable reveals their prideful spirit.

THREES: Deceit. Threes value appearance over substance. Abandoning their true selves to project a false, crowd-pleasing image, Threes buy their own performance and deceive themselves into believing they are their persona.

FOURS: Envy. Fours believe they are missing something essential without which they will never be complete. They envy what they perceive to be the wholeness and happiness of others.

FIVES: Avarice. Fives hoard those things they believe will ensure they can live an independent, self-sustaining existence. This withholding ultimately leads to their holding back love and affection from others.

SIXES: Fear. Forever imagining worst-case scenarios and questioning their ability to handle life on their own, Sixes turn to authority figures and belief systems rather than God to provide them with the support and security they yearn for.

SEVENS: Gluttony. To avoid painful feelings, Sevens gorge themselves on positive experiences, planning and anticipating new adventures, and entertaining interesting ideas. Never satisfied, the Seven’s frenzied pursuit of these distractions eventually escalates to the point of gluttony.

EIGHTS: Lust. Eights lust after intensity. It can be seen in the excessiveness they evidence in every area of life. Domineering and confrontational, Eights present a hard, intimidating exterior to mask vulnerability.

NINES: Sloth. For Nines, sloth refers not to physical but to spiritual laziness. Nines fall asleep to their own priorities, personal development and responsibility for becoming their own person.

The Nine Types in Childhood

It’s staggering to think how many messages our uncritical minds and hearts pick up and internalize in childhood, and how many hours and dollars we later spend on therapists trying to pick them out of our psyches like burrs from the coat of a sheepdog. Some messages and beliefs we unconsciously take in as kids are life giving, while others wound. Most of us unknowingly surrender our lives to the messages that most perforate our beauty. We should remind ourselves of this more often. We would be kinder to each other if we did.

In the chapters that follow we’ll take a look at how each number tends to play out in childhood, with Twos learning to happily give up their Cheez-Its at lunch to buy love and Fives observing the other kids’ play before tentatively deciding to join in. These kids are reflecting both their natural tendencies and the mask they are unconsciously hoping will protect them. They are growing into their number.

The good news is that there are healing messages that we can choose to change the direction of our thoughts, beliefs and behaviors. Learning a healing message unique to each number is a useful aid to help us along on our journey back to our true selves, to the wholeness we crave. It can become a salve of compassion for ourselves, teaching us to respond to old patterns by reminding us to let go of the false self we developed to protect ourselves in childhood and to put on the true self.

Your Type in Relationships and at Work

I once worked with a person whose self-awareness quotient was so low as to be unquantifiable. His lack of self-knowledge and inability to self-regulate wounded so many of his colleagues that he should have been removed by OSHA as a workplace health and safety hazard.

The truth is, people who lack self-knowledge not only suffer spiritually but professionally as well. I recently read a Harvard Business Review article in which the entrepreneur Anthony Tjan writes, “There is one quality that trumps all, evident in virtually every great entrepreneur, manager, and leader. That quality is self-awareness. The best thing leaders can do to improve their effectiveness is to become more aware of what motivates them and their decision-making.” Numerous other books and articles on the topic of self-awareness in magazines from Forbes to Fast Company all say the same thing: know thyself.

In this book, we’ll look at a few ways the behaviors associated with our particular number can help or hinder us as we perform our work and relate to colleagues. It can also help us in the process of discerning what career path we should pursue, whether we’re currently on the right one for us, or whether the professional environment we’re currently working in is a good fit based on the strengths and liabilities of our personalities.

God wants you to enjoy and be effective in your work (unless, like my wife, you’ve chosen to teach eighth grade, in which case you got the pizza you ordered). By expanding self-knowledge and self-awareness, the Enneagram can help you perform better and experience more satisfaction in your vocation, so much so that companies and organizations like Motorola, the Oakland A’s baseball team, the CIA and clergy from the Vatican, among many others, have used it to help their people find more joy in their work. Even Stanford University and Georgetown University’s business schools have included it in their curriculums.

The Enneagram also offers great insight into how our personality types engage in relationships with partners or friends and what we most need and fear from those interactions. All of us bring some amount of brokenness to our connections with others, but you should understand that every single number on the Enneagram is capable of healthy and life-giving relationships. Every number has its healthy, average and unhealthy range of behaviors. With greater self-awareness, you can help ensure that your typical behaviors land more on the healthy side and don’t sabotage your interactions with the people you love the most.

“I love a lot of people, understand none of them.”

Flannery O’Connor

Spiritual Formation

“Accepting oneself does not preclude an attempt to become better,” observed Flannery O’Connor, and she’s right. Your Enneagram number is not like a note from your mother that you can hand the universe whenever you behave badly that says, “To Whom It May Concern, you must excuse my son John. He is a Nine (or whatever John’s number might be) and is therefore incapable of acting any better than what you’ve witnessed him do to date.” If anything, once you know your Enneagram number it takes away any excuse you might have for not changing. Now you know too much to cop the “This is just who I am so deal with it” plea.

Recently in an AA meeting I heard someone say, “Insight is cheap.” Man, is that ever true! As Fr. Rohr points out, “Information is not transformation.” Once you know your type you owe it to yourself and the people you love (or don’t love, for that matter) to become a kinder, more compassionate presence in the world. May a pox fall on anyone who reads this book and walks away with no more than something “interesting” to prattle on about at a dinner party. The purpose of the Enneagram is to show us how we can release the paralyzing arthritic grip we’ve kept on old, self-defeating ways of living so we can open ourselves to experiencing more interior freedom and become our best selves.

At the end of every chapter you will find a spiritual transformation section that offers each type a few suggestions on how they can put what they’ve learned about themselves to good use. This is helpful information so long as you don’t waste your time trying to accomplish any of it apart from the transformative power of God’s grace. Anyone who says they’re “trying” to be a good Christian right away reveals they have no idea what a Christian is. Christianity is not something you do as much as something that gets done to you. Once you know the dark side of your personality, simply give God consent to do for you what you’ve never been able to do for yourself, namely, bring meaningful and lasting change to your life.

How to Read Each Chapter and Figure Out Your Type

It’s tempting, but as you read the chapters that follow, don’t try to type yourself solely on the basis of behaviors. At the start of each chapter you will find a list of “I” statements designed to give you a sense of how people of that particular number might describe what it’s like to live in their skin. Keep in mind as you read these lists, however, that your number is not determined by what you do so much as by why you do it. In other words, don’t rely too much on traits to identify your type. Instead, read carefully about the underlying motivation that drives the traits or behaviors of each number to see whether it rings true for you. For example, several different numbers might climb the ladder at work, but the reasons they do so are very different: motivated by a compulsive need to improve things, Ones might seek advancement because they’ve heard only people in top management have the authority to fix the countless imperfections the One can’t help fixating on in the company’s day-to-day operations; Threes might climb it because getting the corner office is important to them; and Eights might scale the ladder just to see who’s stupid enough to try to stop them. Motivation is what matters! To find your number ask yourself why you do the things you do.

It will help you identify your type if, as you read along, you think back to what you were like at age twenty rather than who you are now. Even though your personality type never changes, it’s never more florid or clear than in early adulthood when, as James Hollis says, you haven’t lived long enough to figure out that you are “the only person who is consistently present in every scene of that long-running drama we call our life”—in other words, the source of most of your problems is you. It’s also important to think more about the way you act, think and feel at home.

Look for the type that best describes who you are, not the type you’d like to think you are or have always wanted to be. If given my druthers I’d like to be a charming, happy-go-lucky Seven like Stephen Colbert, but I’m a garden-variety “Bob Dylan” Four minus the talent. (Throughout the book I give examples of famous people for each number. These are guesses on my part, not self-reported by the people themselves.) As Anne Lamott says, “Everyone is screwed up, broken, clingy, and scared,” so there’s no sense wanting to be differently screwed up than you already are. As you try to figure out your type, it’s great to ask your close friends, spouse or spiritual director to read the descriptions and offer their opinions about which type they think sounds most like you—but don’t kill the messenger.

If while reading a description you begin to feel squeamish because it’s captured your inner world in a way only someone who hacked into the server where you back up your personality could know about, then you’re probably zeroing in on your number. When I first read my number I felt humiliated. It’s not pleasant to be the rat in a dark kitchen who is so focused on devouring crumbs that he doesn’t hear the stealthy homeowners approaching and therefore doesn’t have time to take cover before they suddenly switch on the light and catch the rat in the act with a bagel in its mouth. On the other hand I felt consoled. I didn’t know there were other rats like me. So if this happens, don’t despair. Remember each number has its assets and liabilities, blessings and blights. The embarrassment will pass, but in the words of novelist David Foster Wallace, “The truth will set you free, but not until it’s done with you.”

Don’t expect to identify with every single feature of your number—you won’t. Just be on the lookout for the one that comes closest to describing who you are. If it’s any comfort, it takes some people several months to explore the numbers and gather feedback from others before they feel confident in identifying their type.

I often hear beginning students of the Enneagram taking what they’re learning about other types and turning it into a weapon to dismiss or ridicule other people. It gets my hackles up when I hear someone say to another person something akin to, “Oh you’re so Six” or “Stop being such a Three,” particularly when the person they’re saying it to has no idea what the Enneagram is. The Enneagram should only be used to build others up and help them advance on their journey toward wholeness and God. Period. We hope you take this to heart.

A few of the type descriptions might also sound suspiciously reminiscent of a family member, coworker or friend. You might feel tempted to call your sister to tell her you now understand the reason she made your childhood a living hell had more to do with her personality type than demonic possession as previously believed. Don’t do this. Everyone will hate you.

“I don’t want to be pigeonholed or put in a box.” People express this concern to Suzanne and me all the time. Fear not! The Enneagram doesn’t put you in a box. It shows you the box you’re already in and how to get out of it. So that’ll be good, right?

Now this is very important: At times, you will feel that we’re focusing far too much on the negative rather than the positive qualities of each number. We are, but only to help you more easily discover your type. In our experience, people identify more readily with what’s not working in their personalities than with what is. As Suzanne likes to say, “We don’t know ourselves by what we get right; we know ourselves by what we get wrong.” Try not to get all pouty.

Finally, have a sense of humor and be compassionate toward yourself and others.

The universe is undemocratic. A man in a white lab coat holding a clipboard didn’t appear at the moment of your conception to inquire whether you preferred to be genetically matched with Pope Francis or Sarah Palin. You didn’t pick your parents, your lunatic siblings or the place you occupy in the family birth order. You didn’t choose the town where you were born or the side of the track on which your childhood home sat. That we were not consulted about these matters has long been a source of contention between God and me. But over time I’ve learned that in addition to sins born of the ego’s desire to have everyone in the world organize their lives around ours, we face many challenges that are not of our own making but which we are responsible to do something about. Either way, always maintain a compassionate stance toward yourself as God does. Self-contempt will never produce lasting, healing change in our lives, only love. This is the physics of the spiritual universe, for which we should all be grateful and say, “Amen!”

And so as Br. Dave would say, “Now we can begin.”