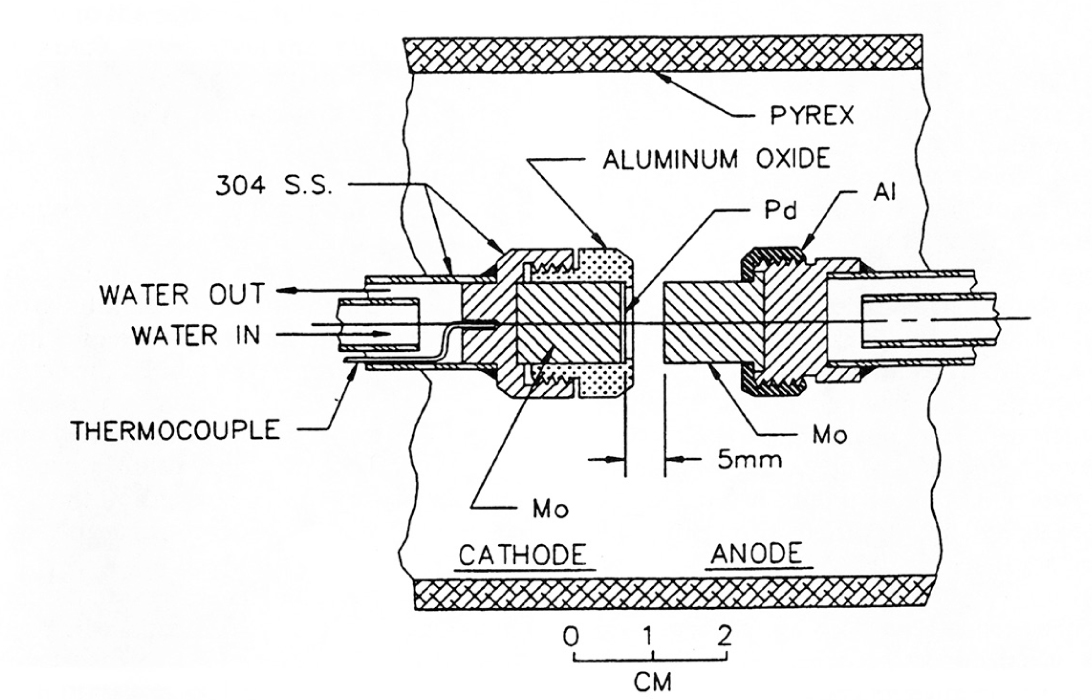

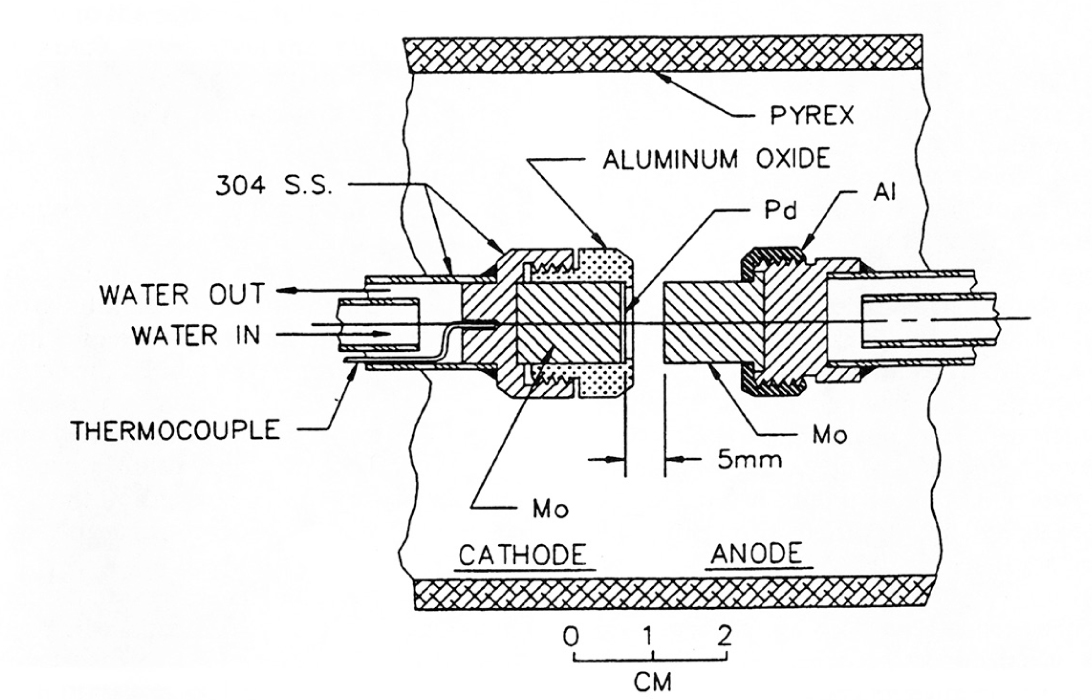

A cross-sectional view of our Kucherov glow-discharge cold-fusion reactor.

“The historian’s mission: to bring out of chaos—more chaos.”

—Robert Harris, Fatherland, 1992

IN THE SEVENTH GRADE, I read a lot of science fiction. I had a subscription to the pulp magazine read by scientists at the Los Alamos nuclear lab, Analog: Science Fiction–Science Fact, edited by John W. Campbell. I read all the classics of the genre in the school library, from writers Robert Heinlein to Alan E. Nourse. My imagination grew expansive, and I daydreamed of space exploration and encounters with faraway civilizations.

At the time, I developed a parallel interest in what were termed UFOs (Unidentified Flying Objects) or flying saucers. The flying saucer spacecraft had become a science fiction staple by then, being used for interstellar travel in such movies as The Day the Earth Stood Still and Forbidden Planet, but the configuration, a dinner plate with another plate inverted on top and an inverted cup topping it off, was not the invention of screenwriters. In this case, art seemed to be copying life. There had been hundreds of sightings of round, flat flying machines that were beyond our ability to construct. Beginning in the late 1940s, newspaper and magazine accounts of flying saucers were appearing often. I read every book on the subject of flying saucer sightings, recovered crashes, and human abductions in the Maud M. Burris Library in downtown Decatur, Georgia. They were cataloged in the basement, under Dewey Decimal 629.133. According to everything I read, we seemed to be on the brink of a solid contact with people from a distant star system, from civilizations more technically advanced than ours.

It turned out that people had been documenting strange sightings for a long time, possibly starting in the Old Testament, where the prophet Ezekiel describes a noisy but soft landing of a manned spacecraft, seeming to touch Earth on four, wheel-equipped struts. Through the centuries, the described machines always seem to be just beyond our ability to duplicate what they were capable of doing. In the nineteenth century, for example, “sky-ships” were seen only at night, from Boston to San Francisco, and they looked like elongated balloons with engine-driven propellers, always with a gimbal-mounted searchlight scanning the ground and blinding Earthbound observers. It was a technology that could be imagined in the nineteenth century, but it was just beyond an ability to own it.

By the 1950s, an unidentifiable flying machine could outrun our fastest jet pursuit planes, turn instantly, hover with a slight wobble, and shut down a car engine by apparently suppressing the flow of electrons in the ignition system. The interstellar explorers in the ship could paralyze a human being, collect data and fluid samples, and almost wipe out his or her memory of having been probed. As in the previous century, they seemed to come at night with their running lights on.

There were obvious hoaxes. In Atlanta in 1953, police officer Sherley Brown happened across an odd-looking burned place in the middle of the street. Getting out of his prowl car to have a look, he met three traumatized witnesses pointing to a body on the side of the road. They claimed that a flying saucer had landed there, aliens piled out, and they hit one with their truck. They could not stop fast enough. The others jumped back into the spaceship and blasted off, leaving that burn on the street surface. Officer Brown could still smell the smoldering tar. The victim looked very small, green, and dead.

The three witnesses, barbers Edward Waters and Tom Wilson and butcher Arnold Payne, together had all the expertise needed to make a dead rhesus monkey look like a Martian. Payne cut off the tail, Waters and Wilson removed the hair using a great deal of depilatory, and a soaking in green food coloring completed the setup. Multiple residents confirmed that a flying saucer had been buzzing around, and a veterinarian confirmed that the creature was not of this Earth. The U.S. Air Force was called to the scene.

The story fell apart quickly when two Emory University doctors, Herman Jones and Marion Hines, took a glance at the corpse. “If it came from Mars, they have monkeys on Mars,” was the last word.224

The most famous and prolific hoaxer was George Adamski in Palomar Mountain, California. He made personal contact with an alien from Venus named Orthon on November 20, 1952, and he had a photograph of Orthon’s spaceship to prove it. Close examination of Adamski’s picture indicated that it was a chicken brooder. The three bright orbs underneath the ship that Adamski identified as landing gear turned out to be three Westinghouse lightbulbs used to warm young poultry. Still, Adamski sold 200,000 copies of his three books, Flying Saucers Have Landed, Inside the Space Ships, and Flying Saucers Farewell.

False sightings and mistakes by inexperienced observers were inevitable, but there were many credible sightings by Air Force pilots, military personnel, entire crowds, and even scientists. Clyde Tombaugh, the astronomer who discovered the once-planet Pluto, gave a detailed report of having seen something strange in the desert sky one evening. Everyone could not be wrong.

The Roswell Incident of June 1947 was the mother of all flying-saucer stories. It had everything: a crashed spacecraft, dead aliens, secret transport of the remains to Hangar 18 at an airbase, and an obvious, massive government conspiracy to cover it up and deny that anything had ever happened. On July 8, 1947, the story hit the newswires. The Air Force had taken possession of a crashed flying disc on a remote ranch near Roswell, New Mexico.225 The “flying disc” had been forwarded to the 8th Air Force at the Fort Worth Army Air Field in Texas.

The next day, the Air Force retracted the story, trying to suppress speculation that they had found an alien spacecraft. A modified press release identified it as a weather balloon that got caught in a downdraft and hit the ground on the Foster homestead. A ranch foreman, Mac Brazel, had noticed a field of odd-looking stuff while on his rounds. It looked like strips of rubber, aluminum foil, sticks, and paper. News of the find got back to the Roswell Army Air Field, home of the 509th Bomber Group that had dropped the A-bombs on Japan. A team was sent to clean up the debris and erase evidence of its having been on the ranch. The story of a crashed flying saucer was cooked up, perhaps too hastily, to hide whatever the weather balloon was doing. A tight lid was pulled over it, and no further information was available from the government authorities.226

After a couple of years of intense research into eyewitness accounts of dramatic flying saucer sightings and encounters, it started to dawn on me, dimly at first, that science is not a democracy. It doesn’t really matter how many people have reported observations if the observations make no physical sense. We don’t take a vote to see if flying saucer attributes, such as antigravity, force fields, and speeds of thousands of miles per hour in the lower atmosphere, are technically achievable. Such features either exist or they do not, and they are judged on compatibility with existing proofs and the results of confirmatory research. There are many strange and even unbelievable phenomena that have been proven and re-proven to exist in the nuclear physics model of the universe, but the capabilities of your common flying saucer are not in this set.

It was possible for everyone who witnessed a flying saucer incident to be simply wrong. In fact, if every person on the planet Earth believes that we have been visited by aliens, that does not make it a correct assertion. Absolutely everyone can be wrong. I was at peace with this scrap of philosophy and was even willing to be proven wrong, but somewhere, deeply buried, there was a tiny detail. It was an unanswered question: what was so utterly secret about a weather balloon that the Air Force would fire off that crazy press release at the Roswell Air Field about a crashed flying saucer just to smother its actual mission?

On Wednesday, April 30, 1989, I was slumped over my desk at the Georgia Tech Research Institute, still taking heat in the slow cooldown from the cold fusion fiasco. People were calling all the time to discuss cold fusion, to propose another experiment, to debate the existence of cold fusion, to float a theory past me, to condemn the rigidity of science in general, or to convince me that I was wrong in my negative findings. I had allowed myself to grow weary of both cold fusion and telephonic communications.

In the midst of these tribulations, a visitor came to the Electronics Research Building, wanting to see me. As it turned out, he and I had sipped from the same fire hose. We had each earned a bachelor of science in physics at Georgia Tech. I replied to the receptionist’s call saying that I would be glad to talk with him. I would be in the conference room. Please send him up.

He introduced himself as Clarence H. “Judge” Ellison, a retired industrialist and physicist, living in suburban Atlanta. He was tall, fair-haired, and getting on in age. That certain rearrangement of the nerve pathways from having done time at Georgia Tech was still there, and he had a twinkle in his eye as he unwound his story as can only a son of the South. When he escaped from school, just as World War II was ending, he had no trouble finding work. The Air Force had new types of airplanes, new types of weapons, and new enemies, and it needed new technical talent fresh out of school. He was hired to work in a top-secret project named “Mogul.” The goal of Mogul was to detect Soviet A-bomb tests from a great distance. The Soviet Union was thought to be involved in a crash program to come to parity with the United States in nuclear weapons, and the fate of western civilization was at stake. Knowing when secret nuclear airbursts occurred was part of the counterstrategy.

It was vitally important that the Soviets not know that we were developing methods to secretly monitor their progress toward making atomic bombs. They had to think that their secrets were still secret, and unfortunately, it had been proven during the last war that our most sensitive activities were riddled with Soviet spies and an impressive intelligence-gathering system. Mogul would have to be as contained and secure as could be managed. All personnel would be thoroughly vetted and monitored twenty-four hours a day, and there would be cover stories on top of cover stories.

Detonating an atomic bomb in the air produces an enormous air-pressure spike, radiating spherically with the speed of sound, with the leading edge reflecting off the ground and causing a secondary shock wave. The effect is similar to that of dropping a depth charge in the ocean to wreck an enemy submarine, and in several decades the navy had developed special, low-frequency microphones, or “hydrophones,” to detect such explosions and sounds caused by submarines. By seeding the ocean surface with a matrix pattern of sonobuoys equipped with hydrophones, connected by radio signals to a surface ship, the source of these underwater disturbances could be triangulated and the exact time and position of otherwise unseen activity could be derived. This developed surveillance system is SOFAR, SOund Fixing And Ranging.

The distances over which these sounds can travel is remarkable. In the ocean, which is a fluid having complex characteristics of temperature and pressure, sound channeling develops, in which low-frequency components of a shock wave can travel 3,000 miles. In Project Mogul it was reasoned that the atmosphere is also an Earth-spanning ocean, only it is made of air instead of water. Theory had it that there were also sound channels in the atmosphere, and it should be possible to pick up the low-frequency components of an airburst from 3,000 miles away. Instead of dropping floating sonobuoys on the top of the sea, they would send special microphones to the top of the atmosphere. Like the sonobuoys, they would be linked to a central receiver by radio signaling. The vehicles would be helium balloons, and the launching point would be Alamogordo, New Mexico, the forbidden place where in 1945 the first atomic bomb had been tested.

Although the principle was simple and it might even work, there were a few technical details to be worked out. Weather balloons, which were by 1948 being used to find the temperature, air pressure, and humidity in the unmeasured regions of the upper atmosphere, would typically rise until the balloon burst. The below-freezing temperatures would make the rubber balloon brittle, and in the low air pressure the helium filling the balloon would expand until the cold rubber reached the end of its elasticity. The Mogul balloons would have to have some sort of automatic altitude control mechanism.

To triangulate the position of a bomb detonation, multiple balloons in different locations would have to detect the blast simultaneously, and the position of each balloon would have to be known when an explosion signal was received from its radio transmitter. There was no Global Positioning System (GPS) in 1948, but the Air Force owned long-range radar systems, able to track airplanes hundreds of miles away by sending out pulses of tightly directed microwave radio waves and receiving back reflections off metal surfaces on the targets. The directional position of a target airplane was derived from the aimed direction of the radar antenna, and the distance was found by timing the returned pulse. Each balloon would therefore have one or more corner-reflector radar targets hanging from a cord, lightweight, made of aluminum-coated paper and sticks, and named “the kite.”

The kite was three flat squares, interleaved at right angles to form a sort of inside-out box. However you looked at the kite, from the side, top, or bottom, you were seeing an inside corner, which will always send an incoming radar signal back exactly where it came from. Think about throwing a basketball against the wall in a rectangular room. Just hitting a flat wall, the basketball will not necessarily fly back into your hands, but if you aim for a corner, be it a ceiling corner or a floor corner, the ball will shoot right back into your cupped hands. That paper kite, which was about 4 feet tall, looked like a battleship on the radar display. A great deal of the microwave pulse sent out by the radar transmitter would be bounced back to the radar receiver, looking like a very big object.

The electronics package to be lofted by the balloons consisted of a navy ERSB (expendable radio sonobuoy), model AN/CRT-1. It was a cardboard tube, 4 inches in diameter and 30 inches long, with a 39-inch telescoping quarter-wave rod antenna sticking out the top. Inside the tube was a lightly constructed aluminum chassis on which was built a low-frequency audio amplifier driving an FM radio transmitter operating at a frequency selectable between 67 and 72 megahertz. An airplane orbiting below the approximate position of the Mogul balloon could pick up and record the signal from the AN/CRT-1 transmitter from 35 miles away, using an AN/ARR-3 receiver screwed into its air-transport rack. A radio operator would sit in front of it to twist the knobs and wear the headphones.

Judge Ellison’s job was to figure out how to reengineer a hydrophone and make it sensitive to “infrasound” signals transmitted in thin air at frequencies below the threshold of human hearing. Together, Ellison’s microphone, the AN/CRT-1, and its batteries weighed 17.5 pounds. In 1947, there were no transistors and certainly no integrated circuits. Today, an FM radio transmitter can be built on a tiny wafer of silicon, but in those days it required five vacuum tubes, a transformer, four coil assemblies, seventeen capacitors, seventeen resistors, and two very heavy carbon-zinc batteries, 1.5 and 135 volts, all connected together with insulated copper wires. It was a masterpiece of optimized design, and it could operate in the near vacuum at 100,000 feet above ground in subfreezing temperatures.

If a balloon goes up, then it must eventually come down, dropping the AN/CRT-1 and its microphone with it. If anyone were to discover it lying on the ground, pick it up, and say, “What’s this?” they would have to shoot him. Any other part of the Mogul package, from the top balloon to the radar corner reflector, could be explained away as a weather-sampling expedition, but the fact that there was a sonobuoy up in the air gave away the entire Mogul project. That is why the tests were conducted in rural New Mexico, where the population density was similar to that of the lunar surface.

The test vehicle was not just a simple balloon with a sonobuoy attached underneath. It was a string of objects, 596 feet long, consisting of three radar corner reflectors, twenty-three polyethylene helium balloons (spaced at 20-foot intervals), four recovery parachutes, a radiosonde weather data transmitter operating at 74.5 megahertz, three automatic cutoff devices set to separate various balloons or ballast at set altitudes, eight aluminum tubes filled with sand ballast, the AN/CRT-1 sonobuoy with special microphone, and a couple of 3-inch metal rings for holding the thing down before letting it go.227

On the morning of June 38, 1947, the Project Mogul contractors, twenty-three men from New York University and the Watson Laboratories at Columbia University, arrived at Alamogordo to test two innovations for the balloon string. They had replaced the troublesome neoprene balloons with much stronger polyethylene units, and the plastic tubes containing the sand ballast had been replaced with aluminum. As is characteristic of such research, they learned something every time they sent up a balloon string and it failed, and the performance was improving incrementally. On June 4, 1947, they released test flight no. 4 and quickly lost sight of it as it climbed away.228

On June 7, events began to unravel at the Roswell Army Air Field, 60 miles from the launch point at Alamogordo. It was reported that the balloon string had come down on the plains east of the Sacramento Mountains. The balloons, still having some lift capability, had dragged the string for miles, shredding the fragile radar corner reflectors and spreading debris over a long stretch of ground. Personnel from Roswell were sent immediately to recover the sonobuoy and especially the “flying disc,” which was the code name of Ellison’s special microphone, before anybody stumbled over it.

I was stunned. Judge Ellison had just filled in the last piece of the puzzle of the Roswell Incident and closed the lid for me. But that was not what he came to talk about.

Project Mogul dried up in 1949, having pioneered polyethylene balloons, altitude maintenance by aerostat, and the infrasound microphone.229 Its mission of bomb-test detection was taken over by high-flying surveillance aircraft having dust collectors to pick up fission debris released into the upper atmosphere by a test explosion. After working on high-vacuum systems at the American Instrument Company in Silver Spring, Maryland, in the 1950s, Ellison moved to Atlanta, developed a unique product, and started a fledgling industry. His company, which flourished back in the 1960s, manufactured cold-fusion neutron generators exploiting the odd properties of palladium. As I absorbed his tale, my head started to hurt. I had fallen not only into the maelstrom of flying-saucer conspiracies but into another cold-fusion wormhole as well. No one could say that working at Georgia Tech Research Institute was not interesting.

Ellison’s patent, number 3,283,193, applied for in 1962, was for an “Ion Source Having Electrodes of Catalytic Material.” His device, named the Activitron, would produce an impressive 2 × 1011 neutrons per second. He produced an eight-by-ten glossy studio portrait of this baby. It looked like an anti-aircraft weapon from a Flash Gordon episode. Set to roll on casters was a metal tower, about 4 feet tall, tapering from bottom to top, with an access door hinged on the front. Atop the tower was balanced a horizontal, chest-high ray gun, complete with a barrel made of polished stainless steel and a bulbous blunt end, ending in a half-sphere. The business end, where one was advised not to stand, was a water-cooled blank metal cap from which high-energy neutrons would stream when you threw the switch into the on position.

Ellison built a factory on Roswell Road, in what is now the service department for a Buick dealership, where he manufactured and sold twenty-three of these devices for use in identifying trace elements using neutron activation. Using Ellison’s Activitron, it required no chemistry to analyze ore samples, bomb debris, things hidden in lead-lined boxes, or any unknown elements obscured in ways making identification impossible. The neutrons streaming out the end of the Activitron were captured by radiologically inert atoms in the sample, becoming radioactive species of the same elements, each readily identifiable by the energies of the resulting gamma radiation. The multichannel analyzers, developed in the 1950s, made it possible to identify gamma rays across their entire energy spectrum using energy-sensitive scintillation detectors. Even better resolution of individual energies could be found using the new lithium-drifted germanium crystal detectors perfected in the early 1960s. An Activitron could count the number of gold atoms in a shovelful of dirt or turn an aluminum oxide crystal into a blue sapphire, and it did not require a nuclear reactor to make the neutrons.

At the zenith of his machine’s popularity, Ellison’s company was bought by the Technical Measurements Corporation. He produced a photo of himself and a small crew, standing at the open tailgate of a Jeep station wagon. The hot end of an Activitron was pointing at the ground, where they were testing for traces of gold for the state geologist in, of all places, the Dawson Forest.

He sold these things all over the world. One wound up in Hungary in 1966, through a trade-restriction loophole in Austria, eventually to an obscure university called Lajos Kossuth. In March 1989, students there had needed a piece of palladium to try the cold fusion experiment, and they took one from the ion generator of the old Activitron, found languishing in a storage room. They used it to log the world’s first confirmation of cold fusion. There was no follow-up publicity following this announcement, so I had assumed that fault was found with their experiment.

I was in an extremely cautious mood, but I had to ask the question. “What was special about the palladium in your Activitron?” I was not ready to grant the Hungarians a legitimate confirmation, but it did seem interesting.

“It was alloyed with a little bit of silver,” he replied. “It kept the palladium from sputtering in the ion bombardment.” Pons and Fleischmann, he thought, were going about loading the palladium the wrong way. In his machine, he would shoot deuterons toward tritium, using 103,000 volts of electricity, and neutrons would result from deuterium-tritium fusions.

To be struck by flying deuterons, the tritium atoms had to hold still at the end of the accelerator run. To accomplish this, the tritium atoms were embedded in the surface of a thin titanium disk. His description of the machine sounded like another version of the well-studied Cockcroft-Walton accelerator, except that the accelerating voltage seemed too low to induce fusion and thus neutrons.230

What made it interesting was the fact that he discovered that his machine would make neutrons with a reduced acceleration potential of 25,000 volts, which seemed impossibly low, and they streamed out at the tritium target end. The palladium cap on the ion generator was used as a controlled leak to dole out deuterons one at a time into the accelerated beam. Although the electrically driven particle-accelerator was sealed tightly and kept at a hard vacuum using pumps, a window at the front end of the long, thin chamber was made of Ellison’s special palladium-silver alloy. Hydrogen atoms, including the deuterium variety supplied from a pressurized tank, were able to migrate through this metal window freely, as if it were not there. Ellison theorized that the individualized, nascent deuterium atoms in the gently accelerated beam improved the deuterium-tritium fusion cross section over the usual deuterium molecules, made of two atoms stuck together.

I asked where I might find one of these machines, that I could try it and see for myself. “I gave two of them to Georgia Tech,” he replied. Efforts to find these instruments in Georgia Tech inventory were deeply disappointing.231 Accounts of his Activitron’s workings were very interesting, but it ultimately suffered from the usual fusion-reactor problem. The power required to run the vacuum pumps and make the high-voltage current far exceeded any energy recoverable from the neutron output. It made no net power.

My path through life intersected with Judge Ellison again in 1994. The Soviet Union had fallen apart, and scientists in Russia who had once worked in defense ministry research were scrambling for something to do. A team consisting of A.B. Karabut, Y.R. Kucherov, and I.B. Savvatimova had discovered cold fusion, submitting a paper to the refereed journal Fusion Technology, “The Investigation of Deuterium Nuclear Diffusion at Glow Discharge Cathode.” Judge had closely studied the experiment and found it very similar to the effect he had observed back in the 1960s on his Activitron. He wanted to duplicate the Russian experiment. I could not help but agree to participate.

I built the reactor in my home shop, machining the parts for the ion chamber and the vacuum system on my metal lathe and supplying the vacuum pumps, high-voltage power supply, and the instrument rack from my personal hoard. I borrowed the neutron detection equipment from the Georgia Tech Nuclear Research Center, and Nancy Wood loaned me a brand new BF3 tube.

The electrodes, spaced 5.0 millimeters apart in the reactor, were machined from pure molybdenum, with water-cooled stainless steel support structures. Ellison paid to have an insulating cap made of aluminum oxide, threaded to screw into the cathode structure and holding a thin disc of palladium against the molybdenum block. From that disk, a streaming out of neutrons would confirm that deuterium was fusing. A thermocouple was embedded in the cathode and wired back to a readout in the equipment rack so that we could monitor the temperature. Kucherov had indirectly specified 44 degrees centigrade.

A cross-sectional view of our Kucherov glow-discharge cold-fusion reactor.

Ellison was right in the middle of assembling the system when one afternoon his front doorbell sounded. He was in the basement, working on something, and he had to put it down, climb the steps, and open the door. There stood a large man saying, “My car is stalled can I use your telephone?”

Ellison lived in Brookhaven, right west of Peachtree Road, in an elegant older house, and this fellow was not from around here. His request would not have been less believable if he claimed to be selling Girl Scout cookies. Ellison hesitated a second, and the stranded motorist took the opportunity to produce a pistol, point it at Judge’s center of mass, and force open the door. His intent was to steal all he could carry and leave in his victim’s car.

Judge was furious, but he had the presence of mind not to wrestle with the robust-looking individual over the gun. He was told to lead him to the bedroom, where he was tied up, hands and feet, using neckties, and left face down on the floor while the robber stuffed his pockets with everything shiny in the drawers. His father’s Patek Philippe pocket watch went into one pocket, and the car keys off the top of the dresser went into another.

Ellison heard him leave the room and open the door to the garage; after a few seconds, the garage door motor started grinding. The miscreant wasn’t very good at tying knots. Ellison ripped his hands free, stomped his feet out of their binding, grabbed his .22 caliber rifle out of the closet, loaded it, and ran to the sound. The robber was in the driver’s seat of Judge’s black Mercedes-Benz 300SD sedan, figuring out how to start the diesel engine. He looked up in time to see Ellison going for the down button for the garage door, and yelled, “Don’t!”

“Too late,” replied Ellison. The door motor backed up and the wooden garage door started down. The robber gunned the Benz in reverse, it smashed handily through the door in an explosion of splinters, shifted into drive, and screeched down the driveway to the street. Ellison emptied his rifle into the back of his car as it sped away, causing several problems with the paint.

Ellison’s car was found hours later in the train-station parking lot on Peachtree. The robber was never identified. Ellison’s wife, traumatized by the event, had the last word. “When you are through with that cold-fusion thing, we are moving somewhere else.”

We changed plans. Instead of housing the experiment in my basement, we set up the equipment in Ellison’s basement so that his wife would never be left alone in the house while he was doing cold fusion. We took our time and made sure that everything was correctly configured. Ellison did the copper plumbing for the water-cooled electrodes, and he built concrete-block shielding in case the thing was successful, started throwing neutrons, and activated his basement into radioactivity. It was an excellent exercise in scientific experimentation, and we did everything correctly, complete with the control experiment, of course, using a pressure tank of radiologically inert hydrogen gas as the inactive ingredient.

The radiation-counting background in Ellison’s basement was established at about 28 events per hour, over a period of nine months, and we simulated an expected neutron flux out of the palladium anode using a 52.5 microcurie californium-252 neutron source. Finally, one night we ran the experiment. We used the best DC-704 silicon diffusion pump oil, liquid nitrogen in the trap, and a molecular sieve in the foreline to get as clean a high vacuum as we could. After an hour of pumping, the pressure was down to a simulation of deep space, at 5 × 10-8 Torr. Ellison carefully opened the valve on the pressure tank full of deuterium gas, adjusted the injection pressure, and addressed the control panel, slowly turning up the voltage across the electrodes to 600 volts, as prescribed by Kucherov. Monitoring the neutron count and keeping an eye on the electrode temperature, we awaited the commencement of fusion. Over a period of eight months, we ran the experiment with some variations nineteen times.

We submitted a detailed paper describing the experiment to Fusion Technology. It was refereed and published in the January 1996 edition: “An Investigation of Reports of Fusion Reactions Occurring at the Cathode in Glow Discharges.” The last sentence in in the paper reads, “Therefore, if copious quantities of fast neutrons can be produced at the cathode of a glow discharge, it is concluded that these mechanisms and any others that are similarly independent of loading, are not responsible.”

The ion chamber made a haunting blue glow, due only to the 600 volts across the electrodes, but in many hours of operation we were unable to find a single neutron over background. The Kucherov cold-fusion idea slid away into obscurity, but I predict that cold fusion by palladium hydride will be rediscovered sometime in the next fifty years. It never goes completely away, but it is possible for everyone who witnesses a cold-fusion incident to be simply wrong.

The Ellisons moved to Cashiers, North Carolina. I, as usual, soldiered on at the Georgia Tech Research Institute.

There are still many more atomic adventures that the world has yet to experience. There is most likely at least one forming up right now, probably but not necessarily on or near the surface of the Earth. Let us hope that it is a beneficial adventure, and not one of the destructive, unpleasant ones. Whatever it turns out to be, it will be deeply interesting, very technical, and out on the scientific shock wave. Be prepared.

_________________

224 This clumsy attempt at hoax was heard around the world, and the model for the flying saucer pilot became the small, green-colored biped that exists to this day in a jar of formaldehyde on a shelf in the Georgia Bureau of Investigation Laboratory. The signal from the first discovery of a pulsar was named LGM-1 from a first impression that it may have come from “little green men.” The stereotype remained in place until the early 1980s, when it was replaced by “the gray,” a thin, bald guy with large, black eyes and delicate hands.

225 The term “flying saucer” was twelve days old when it was used in the Roswell Daily Record top story headline on July 8, 1947: RAAF CAPTURES FLYING SAUCER ON RANCH IN ROSWELL REGION. It was first used on June 26, 1947, in the page-two headline: SUPERSONIC FLYING SAUCERS SIGHTED BY IDAHO PILOT; “Speed estimated at 1,200 miles an hour when seen 10,000 feet up near Mt. Rainier,” in the Chicago Sun. On June 24, 1947, Kenneth Arnold, a fire-extinguisher salesman from Idaho, was flying to Yakima, Washington, in a CallAir A-2 airplane, when he saw out the left window a string of nine shiny things flying around Mt. Rainier. They looked like “saucers skipping on water” glinting in the sunlight, and they seemed as if they were tied together on a string, moving like the tail on a Chinese kite. Seeing them go behind the mountain, he estimated the distance at 25 miles and saw enough detail to say that they were “crescent-moon-shaped,” they had to be bigger than DC-4 airliners, or over 100 feet wide. Arnold thought they might be experimental military aircraft or possibly visitors from another world. Thus was born the flying-saucer phenomenon.

226 The weather-balloon cover story was weak, but it was the last word on the Roswell flying-saucer crash until 1980, when Charles Berlitz and William Moore rounded up ninety witnesses who had been there, interviewed them all, and wrote The Roswell Incident. In their research, the authors found that the debris field reported by the Air Force was only a touch-down point for the disabled spacecraft. It actually came to a stop miles from there, digging a trench and coming to rest against a hill. One of the crew was found hanging out of the opened hatch, and every one inside was dead on impact. This imaginative account was never mentioned in any story from 1947, but it bears a resemblance to another story from the Land of Enchantment in 1948 that was widely published. In March of that year, a large, disc-shaped spaceship, 99 feet in diameter, unsuccessfully attempted a controlled landing in Hart Canyon, New Mexico. The nearest town was Aztec. The Air Force quickly gained control of the crash site and transported the craft plus the sixteen dead humanoids found inside to Hangar 18 at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio for analysis. A strange detail was that the crew was dressed in Edwardian livery, as if they had expected to land in 1890 and didn’t want to stand out. Frank Scully wrote about the incident in his book, Behind the Flying Saucers, in 1950. A few years later, the incident was revealed as a hoax cooked up by Silas M. Newton and Leo A. Gebauer. The scheme was to sell a device that could detect oil, gas, and gold, based on technology found aboard the spacecraft that had crashed near Aztec. Both men began to serve time for fraud in 1953. The Air Force claimed to be unaware of a spacecraft crash, anywhere, ever.

227 Ellison’s infrasound microphone looked like a snare drum, about 2 feet in diameter, and it was supported with its axis vertical by three cords, right above the AN/CRT-1, which was mounted upside down with its antenna pointed earthward. It was almost the last object in the 300-foot string. Below it was the sand ballast, supplied with a barometric cutoff that would drop it if the balloon string dropped to a specific altitude. Certain balloons in the string would be automatically cut away at 40,000, 42,500, and 45,000 feet, indicating that the optimum operating altitude to catch the sound channel was between 40,000 and 45,000 feet. The batteries supplying power to the AN/CRT-1, four size D flashlight cells plus two 67.5 volt batteries, would only last for four hours. If Mogul wanted to continuously monitor the Soviet A-bomb testing, then at least two balloons would have to be released every four hours for several years. As soon as they had figured out how to keep a balloon up for more than four hours, the next problem was going to be extended battery life.

228 On May 29, 1947, flight no. 3 was released. It was a configuration duplicate of flight no. 4. The balloons apparently ran into high-speed wind at altitude and disappeared from radar heading north. Flight no. 3 was never recovered. Kenneth Arnold’s sighting twenty-six days later, on June 24, 1947, of a string of nine shiny objects, flying as if they were tied together “like a Chinese kite tail,” may be a description of the top segment of the Mogul balloon vehicle, blown all the way up to Mt. Rainier in the high-altitude jet stream. The top segment was separated from the rest of the string by an electrically activated explosive squib as it reached 45,000 feet. That portion of the vehicle string would have been nine polyethylene balloons, looking highly reflective and metallic at a distance. The top two would have been big, 1-kilogram balloons, separated by 36 feet of braided nylon rope (“lobster twine”). After another 79 feet of rope, a series of seven smaller, 350-gram balloons would have followed, each spaced at 20-foot intervals. If so, then Arnold’s description of the speed and distance of the objects would have been misjudged.

229 A remainder of the Mogul infrasound microphones exists today in the ground-based geophysical MASINT, Measurement And Signal INTelligence system, which is installed worldwide. On February 15, 2013, a meteor, coming in at a shallow angle above Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, exploded 97,400 feet overhead. About 1,500 people were injured and 7,200 buildings in six cities around Chelyabinsk were damaged by the shock wave. It was the equivalent of setting off a 500-kiloton atomic bomb high above the city. The blast was picked up by MASINT microphones all over the world, and the data from these measurements were used to calculate the size of the energy spike, which was exactly what the Mogul balloons were supposed to do if the Soviets tested a nuclear device after World War II.

230 When Ellison delivered an Activitron to a middleman buyer in Austria, it was strictly forbidden to export an object containing radioactivity. The Activitron was completely inert except for the deuteron target, which was a 1-inch disk of titanium saturated with tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen with a 12-year half-life. When the Austrians asked advice on how and where they could get the 10-curie tritium source for use in the new Activitron, to their shock Ellison pulled it out of his shirt pocket and laid it on the table. Yes, it was an extremely active source of radiation, but the beta rays produced by the tritium are too weak to make it out of a paper envelope. The radiation from the tritium-infused titanium was not only perfectly safe to handle, it could only be detected by dissolving it in a scintillator fluid. He had walked through the airport terminals with no fear of being stopped and searched for radioactivity.

231 I finally found evidence of an existing Activitron in Sydney, Australia, and I made a trip there to find it, giving cold-fusion lectures at the University of New South Wales in Sydney and the University of Western Australia in Perth. The Activitron was not available for inspection. One Australian scientist got up and angrily claimed that an Activitron could not possibly work, and he had refused to sit through a demonstration of it. Another said it was being considered for use to irradiate luggage at the airport, detecting barium-based explosives by neutron activation.