2

The Marketplace for Fine Art

Rapid wealth accumulation, social media as a platform for self-promotion, and global demand for art collided in a spectacular way when an Amedeo Modigliani painting was offered for sale in November 2015. It depicted a full-length nude with brunette hair and luscious red lips reclining provocatively on a blanket. Modigliani certainly loved reclining nudes, with this painting from 1917 among the strongest of the twenty-two he made.

The painting was reportedly tucked away in a Swiss warehouse by Laura Mattioli Rossi, an art historian who was bequeathed the painting after her father, Gianni Mattioli, passed away in 1977. Gianni was a passionate collector who set out in the middle of the last decade to assemble a collection of important works by modern and contemporary Italian artists. Modigliani, born and raised in Livorno, Italy, was a prime candidate for the collection. Gianni had not only the desire to collect but also the means due to a successful career in Milan as a cotton merchant. He bought the Modigliani in 1949 as part of a larger purchase of eighty-seven works of art being sold by another Italian collector.1

From cotton wealth to wealth created from the reform of China’s economy, the painting is now owned by one of the wealthiest people in China. Born in 1963, Liu Yiqian started from humble beginnings. He dropped out of middle school and was briefly a salesman in a family handbag business before becoming a taxi driver. In the 1990s, he made his first fortune speculating in the new Shanghai stock market. He is now the chairman of Sunline Group, a diversified holding company.2

Mr. Liu and his wife have been collectors for more than two decades, focused primarily on Chinese works of art. In April 2014, they bought an Imperial Ming dynasty porcelain cup for $36.3 million; Liu then became notorious in China for using his new purchase to have a cup of tea. Seven months later, he bought a fifteenth-century Tibetan tapestry for $45 million. They have two private museums in Shanghai to showcase their collections, with another one on the way. The couple decided recently to start collecting masterpieces of Western art. “We need to collect foreign art so that our museums can be on a par with their foreign peers. Foreign countries have really [sic] a lot of museums, big and small, public or private. But we think China is lacking something when it comes to art … Even if we have enough food, we will be empty inside if we don’t have spiritual fulfillment,” said Liu’s wife.3

Within days of acquiring the Modigliani at auction for a record $170 million, they embarked on a global media campaign to announce their purchase and make it known that it would soon be on view in one of their museums. In those few days, the world learned about Mr. Liu’s wealth and new collecting interests. The owners of Western masterpieces were also happy to discover another buyer potentially willing to pay extraordinary sums for work in their collections.

From collectors like Mr. Liu, to a millennial spending part of their first bonus on a print, the wonderful world of art is propelled forward by a marketplace that employs hundreds of thousands of people around the world. The purpose of this chapter is to describe the important services provided by the four key sectors of the art market: art galleries, art fairs, auction houses, and art advisors. To provide some context, I start by describing how bifurcated the art market is today between selling beautiful, lower-priced items to a large audience and headline-grabbing sales involving a small number of extraordinarily expensive objects. I also touch on why the demand for art has increased, especially for living artists. Appreciating these trends, and the risks associated with them, helps explain some nuances in how the art market works.

WINNER TAKE ALL

Approximately $64 billion of fine art and antiques were sold globally in 2015, as reported by The European Fine Art Foundation (TEFAF).4 To put that in perspective, this was about sixteen times the sales of Tiffany’s and 60 percent of sales at Amazon.

Where do people buy art? Based on the value of the objects sold, the market is roughly evenly split between art galleries and auction houses.5 This has been true for a number of years. But if we use the number of objects sold rather than value, sales through galleries would represent the lion’s share of global sales activity. This is due to extraordinarily valuable masterpieces being sold more frequently at auction, inflating sales totals in that channel.

What type of art are people buying? Detailed numbers only exist for auction sales. Using them, TEFAF estimates the top category was Postwar and Contemporary, at 46 percent of the total value of sales. The runner up was Modern Art at 30 percent, followed by Impressionist and Post-Impressionism at 13 percent and Old Masters at 13 percent.6

What do people spend to buy a piece of fine art? Less than what you may think. TEFAF estimates that 90 percent of auction sales were for objects worth less than $50,000. But these objects represented only 12 percent of the value of auction sales. Most of the remaining balance was associated with the sale of extremely valuable objects. About 2,500 objects sold for more than $1 million in 2015, representing in total almost 60 percent of the value of auction sales.7

How many artists sell at auction? While it varies year to year, work by fifty-nine thousand living and deceased artists was sold at auction in 2015. While this number gives a sense for the breadth of the market, the much more interesting story is that a small number of names accounts for most of the value of sales: about six hundred artists made up 57 percent of total auction sales.8 Like many talent markets, the art market is one of “winner take all,” where the top names capture most of the rewards and the rest sell for far less.

MEANS AND DESIRE

Art is the ultimate discretionary purchase made by those who have the means and desire to own precious objects. The number of people with the means to acquire art has increased sharply, as has the subset that desires it.

Close to thirty-four million people around the world now have a net worth of at least $1 million, up from approximately fourteen million in 2000.9 Further up the pyramid, 124,000 individuals globally are worth at least $50 million.10 The number of billionaires has also increased. My favorite measure of extreme wealth is the price of entry to the Forbes list of the four hundred richest people in the United States. In 2015, one needed $1.7 billion to join the club, almost twice what it was ten years ago. It is also a club that excludes many: 145 billionaires in the United States missed the 2015 list because the bar was so high.11

But means alone does not make an art collector. Three factors are behind the increased desirability of art: education, exclusivity, and opportunity cost. The triumph of liberal arts education has led to greater awareness of art and higher demand for art and design in daily life. Almost sixty-nine million people in the United States now have four or more years of higher education, an increase of twenty-four million since 2000.12 Cultural literacy in this large pool of individuals is an important social requirement to effectively navigate the worlds of business, finance, and professional services. Once culturally literate, it is a relatively short hop to getting involved with the worlds of art and design and experimenting with collecting.

Conventional and social media have also enhanced the sense of exclusivity associated with owning art. Museum curators share stories with me regularly about tours they lead where visitors are excited to see paintings they have only experienced digitally. Ironically, the easy availability of digital images has made the original artwork seem even more precious and valuable. Moreover, as high-quality clothing, restaurant meals, and vacation travel have become more readily available, many luxury goods and services are now viewed as far less exclusive and special. Unique objects created by artists, in contrast, have soared in perceived value. Owning them becomes a way to communicate social status and taste in ways no longer possible with many other luxury goods.

Finally, changes in financial markets have lowered the opportunity cost of owning art. Low interest rates make owning non-yielding assets like art more attractive. Since the financial crisis, the rate on one-year US Treasury Notes has been less than 1 percent, down from around 4 percent in the middle of the last decade. Banks and non-bank financial institutions are also now willing to lend money against a portfolio of high-quality art, upending the historical norm of art being a highly illiquid asset.13

But as a discretionary purchase, collectors can easily elect to defer buying something. Likewise, discretionary sellers can decide to postpone selling work if they feel there may be a lull in buyer demand. Speculators eager to participate in the market when it is on an upswing can just as easily elect to sit out when there is market uncertainty. Taken together, this can lead to sharp changes in sale volume in the art market.

Consider, for example, what happened over the past few years in the market for especially valuable works of art. An important collector shared with me his notes from meetings with auction specialists in early 2015 when they were trying to entice him to sell valuable paintings in his collection by Pablo Picasso and Andy Warhol. They told him the auction market was at an all-time high, driven by new and seasoned collectors, and that many of the new buyers had no “price-point barriers.” When quizzed about what that meant, the specialists told him stories of extraordinarily wealthy new buyers intent on quickly building collections of masterworks by twentieth-century artists. Their drive and ambition made them comfortable bidding far above prices paid earlier in the decade. The upward spiral of prices also led many seasoned collectors to believe that the value of art had structurally adjusted higher, which made them feel comfortable jumping in. The auction specialists felt confident they had the inside track on demand because of their relationships with the exceedingly small group of people willing to spend millions on art. They told him approximately 140 people worldwide had the means and desire to spend $50 million or more on a work of art. For objects worth around $20 million, there were maybe three hundred potential bidders, and at $5 million, the number was closer to one thousand.

To entice masterpiece owners to sell works in 2015, auction houses (sometimes in partnership with third-party speculative capital) took on enormous financial risks. Owners were given generous financial guarantees that their works would sell for at least a minimum price (e.g., $10 million), with a share of the upside going to them if the work sold for more than the guaranteed amount (e.g., 80 percent of the upside above $10 million).

Competitive pressures between auction houses led them to ante-up guarantee amounts and upside-sharing percentages as potential sellers played them off each other. Specialists acquiesced to these demands to keep their auctions full of high-status artworks. Their actions were reminiscent of financial institutions in 2007 right before the financial meltdown, when Charles Prince, the CEO of Citigroup, famously said “As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance.” But many of these guarantees soured when buyers were unwilling to stretch as far as auction house specialists estimated. It turns out that 2014 was the market peak. The financial pain auction houses suffered caused them to be far more parsimonious when negotiating guarantee deals in 2016. With less of this protection available, many discretionary sellers elected to sit on the sidelines. The supply side effects of fewer masterworks from discretionary sellers and less work being sold because of the traditional 3Ds (death, divorce, and debt-related problems) contributed to a drop in auction sales. Christie’s and Sotheby’s reported that first-half sales in 2016 were off by almost 30 percent.

But when great work did come to market, some members of the extremely small group of buyers with the means and desire to spend millions on art still elected to show up. In June 2016, Sotheby’s offered a Modigliani painting of his common-law wife, Jeanne Hebuterne. Unlike the reclining nude bought by Mr. Lui, Modigliani painted her fully clothed and sitting upright in an armchair. It sold for $56.5 million.

BEST TIME TO BE AN ARTIST

Collectors have been passionate about contemporary art for hundreds of years. In 1479, for example, the Doge of Venice sent a prominent artist to work in the court of Sultan Mehmed as part of a peace settlement. Gentile Bellini spent almost two years in Constantinople working for the sultan, who had a particular love for contemporary Italian art and decorative objects. Bellini painted portraits of court members and at least one of the sultan. When he returned to Venice, Bellini was able to return to paintings that he had previously started in the Doges Palace. His portrait of the sultan now hangs in the National Gallery in London.14 While today we think of Bellini as an old master, he was at one time a contemporary art star.

Work by living artists is often easier for new collectors to appreciate, because it is an expression of the zeitgeist in which they live. They do not need to learn about another historical period to gain full appreciation for the art. Interest in living artists is at an all-time high now, in large measure because there are simply so many new collectors. Many established collectors who understand the full sweep of art history also like trying to “see around the corner” and enjoy buying work by living artists who they believe have a chance of making it into the history books. Living artists have an additional advantage over their deceased forbearers: studio visits. A lot of art is sold every year by artists hosting buyers at their studios—so much so that some collectors refuse to go for fear they may be seduced into buying based on the charisma of the artist, rather than the merits of the work.

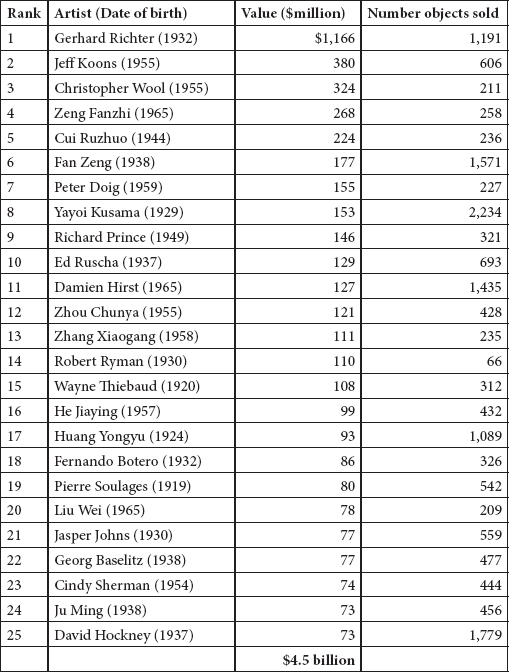

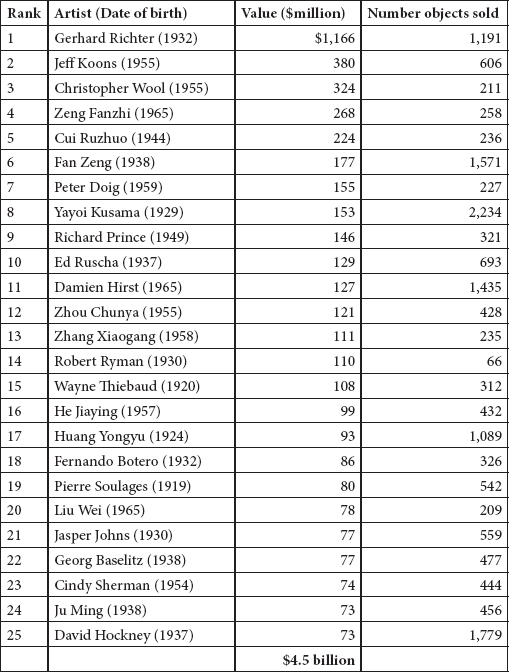

At the very top of the artist pyramid is a small group, no more than three hundred to five hundred artists, who today likely earn in excess of $1 million a year.15 They tend to be represented by the best galleries, enjoy support from important museum curators and tastemakers, and make work that is generally easy to recognize. These artists are sometimes referred to as “branded artists.” The top twenty-five based on recent auction sales are shown in Exhibit 2.1. Gerhard Richter is at the top of the list with $1.2 billion of sales; David Hockney is twenty-fifth with $73 million of auction sales.

Moving down the pyramid, thousands of artists are now able to sell enough of their work to earn at least the median household income of $56,500. A middle-class life, combined with the chance to become an art-market superstar, has led more people than ever before to pursue being a professional artist. The Yale School of Art and the Visual Arts Program at Columbia University are two of the top masters in fine arts programs in the United States. While an advanced degree is by no means required to be a successful artist, acceptance rates at these two programs were 5 percent and 2 percent in 2014, lower than the odds of getting into Harvard or MIT as an undergraduate.16

THE ART-MARKET ECOSYSTEM

Let’s turn now to brief overviews of the services provided by each of the key sectors of the art market: art galleries, art fairs, auction houses, and art advisors.

Art Galleries Select and Promote Artists

Because there are thousands of living artists and artist estates, galleries play an important role filtering this universe to identify those who have commercial potential. Galleries then market the artist’s work to collectors, museums, and art-world influencers. This is the so-called primary market, because it is the first time the work is offered for sale after leaving the artist’s studio.

For many dealers, as for artists, the work is a calling, not a job. But like other businesses, galleries live and die based on sales and their ability to manage their infrastructure costs. As a general rule of thumb, artists and galleries split sale proceeds fifty/fifty, with the gallery responsible for the costs associated with showing and promoting the work. These can include the costs to stage shows, exhibition catalogues, and opening events. Galleries may also be called upon to help cover production costs and advance money to artists against future sales. Well-known artists in high demand can sometimes negotiate more advantageous selling agreements, perhaps receiving as much as 90 percent of sale proceeds.

The world of art galleries is one of the few industries that have been led for years by women. After World War II, for example, Denise René opened her eponymous gallery in Paris devoted to abstract art. She later opened additional galleries in New York and Germany. In honor of her career, the Pompidou Center held an exhibition in 2001 titled The Intrepid Denise René, A Gallery in the Adventure of Abstraction. Another important leader was Ileana Sonnabend, who opened her first gallery in Paris in 1962. She introduced European collectors to postwar American artists like Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol and reversed the flow of introductions when she showed European artists like Gilbert and George, Mario Merz, Piero Manzoni, and Jannis Kounellis in her New York gallery. A list of just some of the many women who run important galleries is in Exhibit 2.2.

Galleries operate in a hierarchical system from those selling expensive, blue-chip art to new galleries run by twentysomethings handling artists just out of school. A gallery’s position in the hierarchy depends on the importance of the artists it handles, the location and quality of its physical exhibition space, the art fairs in which it participates, and its relationships with collectors, curators, critics, and other art-world influencers. Because it can be hard to evaluate the importance of an artist, many buyers rely on the brand of the gallery (i.e., its position in the gallery hierarchy) to help them decide whether the artists represented by the gallery are important.

Given the costs and risks associated with representing an artist, scale is now more important than ever before to running a successful gallery. The largest galleries tend to represent many artists, so they always have something of interest to sell collectors. They have exhibition spaces in several of the major locations where collectors congregate, and they participate in numerous art fairs to stay in touch with as many top collectors as possible. They have talented staff to manage artist and client relationships and curate the numerous shows they put on each year. They have sophisticated back-of-house operations to handle all the valuable objects that flow through their gallery networks. Senior staff in these galleries also tend to have their finger on the pulse of what top collectors are looking to acquire and use this information to help source art in the secondary market for them to buy. Secondary market sales are now an especially important and lucrative part of running a large gallery network. Some of the scale galleries with global exhibition programs are shown in Exhibit 2.3.

A benefit of scale to the larger public is that these galleries can afford to put on museum-quality shows. The Gagosian Gallery, for example, organized in 2009 a retrospective of Piero Manzoni, a major figure in the Italian Arte Povera movement. The show reintroduced the deceased artist to an American audience and was a critical success:

Manzoni’s work has, in general, been a mystery in the United States: familiar, sort of, from books, but fuzzily grasped and seldom seen. Sonnabend Gallery organized a survey in 1972. Then there was pretty much nothing until “Manzoni: A Retrospective,” now at Gagosian Gallery in Chelsea. Maybe that’s why the show feels like such an amazement.

The situation is different in Italy, where Manzoni (1933–1963) is a major presence, both as a pivotal player in the country’s post–World War II avant-garde, and as a progenitor of the homegrown version of Conceptualism known as Arte Povera. The curator who gave that movement its name, Germano Celant, is responsible for the Gagosian show.17

Everyone passionate about art benefits enormously from these types of shows, not only because they see wonderful art for free but also because of the scholarship that typically goes into the exhibition catalogues.

Art Fairs Provide Convenience

From essentially nothing twenty-five years ago, art fairs are now one of the most important venues where people buy art. Close to 40 percent of worldwide gallery sales are conducted at art fairs.18

Art fairs are important because they meet three collector needs:

• Convenience. Collectors are time-starved, like everyone. Art fairs enable them to see art from many different dealers in a concentrated period. Fairs are especially important for collectors who do not live in one of the major art hubs and want to keep up with market trends.

• Comparison shopping. Buyers can easily compare work by the same artist that is being shown by different galleries at the fair. Collectors can also see work by many other artists, enabling them to make price and value comparisons about what to acquire.

• Social engagement. Art fairs are an opportunity to see and be seen. Collecting is a specialized activity, so collectors do not have many opportunities to spend time with like-minded people. Art fairs are a moment in time when collectors, curators, art advisors, and others passionate about art come together.

One of the largest art fairs is Art Basel Miami Beach, held every year in early December at the Miami Beach convention center. The seventy-seven thousand people who attended it in 2016 walked through the equivalent of four football fields of art displayed in more than 250 individual booths, each one representing a gallery who paid substantial fees to be there. Tens of thousands of artworks were on display and available for sale. The show is open to the public and all are welcome.

While art fairs are sometimes derided as crass sales emporiums, they deliver a buying experience enjoyed by many collectors. For an up-to-date calendar of art fairs taking place around the world, consult the gallery apps mentioned at the end of Chapter 1. Most of them have information on upcoming art fairs.

Auction Houses Provide Price Transparency

Auction houses are trading platforms, similar in nature to the New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ, where buyers and sellers meet to exchange art for cash, with a public record of whether the object sold and for what price.

Like stock exchanges, buyers and sellers migrate to the platform with the most liquidity. Participants, however, will resist a single auction platform from forming because it would wield monopoly power. But if there are too many platforms, liquidity is fragmented to the detriment of buyers and sellers. As a result, the fine art auction market in Europe and the Americas tends to be a duopoly with most auction sales occurring at Christie’s and Sotheby’s, followed by Phillips and Bonhams, and then a handful of regional players and some online specialists like Paddle8 and Artsy.

The downside of duopolies is that they invite collusion. This is what happened in the 1990s, when executives from Christie’s and Sotheby’s colluded to raise commission rates. Executives were prosecuted and jailed, and the auction houses paid $512 million in fines.19 Since then, auction houses have competed ruthlessly to win selling mandates.

Due to their global scale and access to lines of credit, the major auction houses are especially useful to collectors looking to sell the following:

• Large collections. Death and divorce, or changes in a collector’s financial circumstances, can trigger a collection sale. Celebrities (Jackie Onassis, Elizabeth Taylor, Joan Rivers), performers (David Bowie, Andy Williams), financial titans (John Whitehead, ex-CEO of Goldman, Sachs), fashion icons (Yves Saint Laurent), and entrepreneurs (Alfred Taubman, a shopping mall tycoon and past owner and Chairman of Sotheby’s), among others, have sold collections at auction. The inside track to selling a collection is covered in detail in Chapter 6.

• Masterpieces. Auctions create a moment in time when the very small pool of buyers with the means and desire to acquire masterpieces must compete for them. Unlike private sales, where it is hard to create a sense of urgency, auctions force bidders to decide whether to participate. Public bidding can also validate for buyers that multiple parties are interested in the work, causing them to bid more.

• Objects with a price guarantee. Selling at auction entails risk to the consignor—risk that bidding will not reach the confidential reserve price (the minimum acceptable sale price set by the consignor). Sometimes consignors will only want to sell at auction if they know with certainty that the object will sell for at least a guaranteed minimum price. Auction houses will sometimes agree to offer a guarantee, either alone, or in partnership with a third party. More information on how guarantee deals work is covered in the appendix titled A Peek Behind the Curtain.

In the battle to win consignments, auction houses sometimes compete by offering ever higher guarantee amounts. In the fall of 2015, Sotheby’s announced that it made a $515 million guarantee to land the Alfred Taubman estate, the largest guarantee in auction history. But the sale of the Taubman Collection performed poorly relative to the guarantee, causing Sotheby’s to book a loss and its stock price to swoon. The story of how the largest guarantee in auction history went awry is covered in Exhibit 2.4.

Art Advisors Are a Solution to Art-World Complexity

With so many wonderful things to buy at so many different art galleries, art fairs, and auctions, it is easy to get overwhelmed. Even when a collector knows exactly what she wants—for example, an abstract work by Gerhard Richter—it is challenging sorting through available work and making quality and price comparisons. With choice comes complexity.

At different points in their collecting journey, many collectors elect to use advisors. To demystify the marketplace for art-related advice, let’s start with different ways advisors can help collectors:

• Collection strategy services. Art advisors can help new collectors decide what to focus on given their interests, their resources, and the time they can devote to collecting. For established collectors, art advisors can help them figure out where to prune or restructure their collection in light of changes in their interests, the art market, or personal circumstances.

• Buyer support services. From strategy comes tactics. Art advisors can help collectors source works of art from the marketplace and negotiate price and terms. Chapter 5 is devoted to this topic.

• Seller support services. Most art advisors can help collectors buy, but fewer of them are skilled in helping collectors sell. The tricky topic of selling art is covered in detail in Chapter 6.

• Collection management services. These are services that help collectors manage and care for their physical art objects. Framing, conservation, installation, and lighting are services art advisors can arrange for clients.

• Credit services. Major private banks, plus a growing number of specialty lenders, will lend money based on some combination of the value of a collector’s art and other assets. Properly trained art advisors can solicit proposals from credit-market providers so the collector gets the best possible deal.

When selecting an art advisor, collectors need to have a clear picture of the type of assistance they need. If they are primarily interested in someone escorting them through a few art fairs and galleries and helping them buy art for a new home, then they need someone who can deliver a terrific buying experience. But if they have been collecting for a number of years and now need to create an art legacy plan, they need an advisor who can help them think through their options and work closely with their tax, legal, and financial advisors. The sometimes-complicated relationship between art, taxes, and legacy planning is covered at the end of Chapter 7.

Collectors need to make sure the advisors they retain will put their interests first, a so-called fiduciary relationship. Clean and simple. They should always have a written agreement that formalizes this obligation and how the advisor will be paid.20 By doing so, it will help them avoid the pitfalls I talk about in “Avoiding the Scoundrel’s Corner” sections, which appear at the end of Chapters 5 and 6 and in the appendix.

One final note about art advisors: auction house specialists and gallery employees are important resources for collectors to draw on for information and advice. But it is important to remember that they are sellers’ agents, not buyers’ agents. The auction house employee is working on behalf of the seller, not the buyer. Likewise, the gallery employee is working on behalf of the artist who consigned work, not the buyer. As a result, advice given by auction house and gallery employees is not fully independent and objective. It is similar to real estate. When you sell your home, the real estate agent you hire is working on your behalf, not the buyer. His or her role is to market the property to potential buyers and sell it for the highest price possible.

* * *

The sexy Modigliani painting of a reclining nude that sold for $170 million was first offered for sale in December 1917 at a Paris show organized by the artist’s new dealer. Until then, Modigliani was painting portraits of fellow artists and the habitués of Montmartre, but few of them had the means to buy anything. His new dealer, Leopold Zborowski, a young upstart looking for artists he could mold and turn into selling machines, suggested that Modigliani paint nudes. Given the rakish charms of the artist and his insatiable sexual appetites, the female body was certainly something he knew a lot about. His nudes became painted sex: pubic hair, luscious ripe colors, and a female gaze of pleasure and satisfaction.

Zborowski was new to the art trade and had yet to open his own gallery. But like all good entrepreneurs, that did not stop him. He partnered with Galerie Berthe Weill to host a show of works by Modigliani that included his nudes. The gallery was located across the street from the local police station, which became a convenient way to manufacture some scandal. After putting a nude painting in the storefront windows and encouraging locals to visit the gallery, the police felt compelled to shut it down for acts of moral turpitude. While raising Modigliani’s profile, it failed to translate into meaningful sales. Two drawings sold and the gallery bought some paintings for inventory, but the now-record-breaking painting did not sell.21

Modigliani finally started to achieve some commercial success about six months before he died in January 1920. The setting was London, not his adopted hometown of Paris. A London department store still in operation today, Heal’s, hosted a group show of works by contemporary artists. Modigliani had more works in it than any other artist, including Picasso and Matisse. Modigliani got the best reviews of his lifetime and sold many works.

But fame arrived too late. He died a few months later at the age of thirty-five. He was essentially a penniless, broken man brought down by his raging egomania, reckless behavior, and a communicable illness—tuberculosis—which he was diagnosed with at the age of sixteen and which he tried to hide from his friends and sexual partners. “People like us … have different rights, different values than do normal, ordinary people because we have different needs which put us—it has to be said and you must believe it—above their moral standards.”22 Modigliani was a lifelong abuser of alcohol and drugs, perhaps to help ameliorate some symptoms associated with tuberculosis. He had a temper and a tendency to act out, and he regularly discarded people, especially women. His common-law wife, with whom he already had one child who they left to others to raise, committed suicide the day after Modigliani died by jumping from a building, eight-months pregnant with their second child. It was Jeanne Hebuterne, the subject of the portrait sold at Sotheby’s in June 2016.

Modigliani’s artistic talents and personal behaviors helped him become one of the most recognized artists of the twentieth century, if not the past five hundred years. When he died, many of the people who were part of his circle sensed that he might be appreciated more after death. His dealer and others with access to his work quickly bought or took title to what they could put their hands on. His artist friends allegedly helped complete unfinished work and created fakes to meet growing demand for his work. Within five years of his death, Modigliani’s work was being sold at auction and traded in the private market for multiples of his pre-death prices. His reputation and the prices collectors are willing to pay for authenticated work have only grown with time, with the wonderful nude painting that was unsalable in 1917 being sold less than a hundred years later for $170 million.

EXHIBIT 2.1

TOP TWENTY-FIVE LIVING ARTISTS BASED ON AUCTION SALES23

2011–2015

EXHIBIT 2.2

ART GALLERY LEADERS WHO HAPPEN TO BE WOMEN

NAME |

GALLERY |

Claudia Altman-Siegel |

Altman Siegel Gallery |

Kristine Bell |

David Zwirner Gallery |

Mary Boone |

Mary Boone Gallery |

Marianne Boesky |

Marianne Boesky Gallery |

Sadie Coles |

Sadie Coles Gallery |

Paula Cooper |

Paula Cooper Gallery |

Virginia Dwan (retired) |

Dwan Gallery |

Barbara Gladstone |

Barbara Gladstone Gallery |

Marian Goodman |

Marian Goodman Gallery |

Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn |

Salon 94 |

Rhona Hoffman |

Rhona Hoffman Gallery |

Susan Inglett |

Susan Inglett Gallery |

Alison Jacques |

Alison Jacques Gallery |

Anke Kempkes |

Broadway 1602 |

Pearl Lam |

Pearl Lam Gallery |

Margo Leavin |

Margo Leavin Gallery |

Dominique Lévy |

Lévy Gorvy Gallery |

Philomene Magers |

Sprüth Magers Gallery |

Lucy Mitchell-Innes |

Mitchell-Innes & Nash Gallery |

Victoria Miro |

Victoria Miro Gallery |

Wendy Olsoff |

PPOW Gallery |

Penny Pilkington |

PPOW Gallery |

Eva Presenhuber |

Galerie Eva Presenhuber |

Shaun Caley Regen |

Regen Projects |

Metro Pictures Gallery |

|

Andrea Rosen |

Andrea Rosen Gallery |

Monika Sprüth |

Sprüth Magers Gallery |

AnneMarie Verna |

AnneMarie Verna Galerie |

Meredith Ward |

Meredith Ward Gallery |

Helene Winer |

Metro Pictures |

EXHIBIT 2.3

EXAMPLES OF GALLERIES WITH A GLOBAL EXHIBITION PROGRAM24

Gallery |

Permanent Exhibition Spaces |

Number of Artists on Website |

Gagosian Gallery |

New York (5 locations) London (3 locations) Paris (2 locations) Los Angeles San Francisco Rome Athens Geneva Hong Kong |

121 |

Pace Gallery |

New York (4 locations) London Paris Beijing Hong Kong Menlo Park Palo Alto |

87 |

Hauser & Wirth |

New York (2 locations) London Los Angeles Zurich Somerset |

66 |

Sprüth Magers Gallery |

Berlin Cologne London Los Angeles Hong Kong |

62 |

David Zwirner Gallery |

New York (2 locations) London Hong Kong (announced) |

54 |

EXHIBIT 2.4

HOW THE LARGEST GUARANTEE IN AUCTION HISTORY WENT AWRY

Alfred Taubman, a real estate and shopping mall entrepreneur, was passionate about art and assembled a large collection of more than five hundred objects. He was also the chairman of the board of Sotheby’s at the time of the price-fixing scandal and went to jail because of his role in it.25 When he died in April 2015, his heirs moved quickly to sell the collection to raise funds for estate taxes and other obligations. Sotheby’s proudly announced on September 3, 2015, that it would be selling the collection. But to win it, Sotheby’s guaranteed the family would receive no less than $515 million from the sale, the largest guarantee in auction history.

When the first of four auctions of Taubman property failed to perform well, Sotheby’s stock price dropped. Once all the sales were completed, total sales proceeds (hammer price plus buyer’s premium) were not enough to cover the guarantee amount. Sotheby’s had to dig into its own pockets to cover the guarantee amount, a disappointment for Sotheby’s employees and its shareholders.

Why was Sotheby’s willing to guarantee the collection for $515 million? The Taubman name has been intertwined with that of Sotheby’s for more than thirty years, ever since Alfred Taubman bought the company in a leveraged buyout in 1983. Sotheby’s felt the Taubman collection was “must win” business. For example, in his 2015 third-quarter-earnings call with securities analysts, the Sotheby’s CEO stated that “only [Alfred Taubman’s] collection had both the size and the unique importance to Sotheby’s shareholders to make this consignment important to win.”26 But Sotheby’s crosstown competitor, Christie’s, also wanted the business. If successful, Christie’s would land a decisive punch and harm the Sotheby’s brand.

Specialists at both auction houses worked feverishly over the summer on their proposals. In addition to creating detailed sales and marketing plans, specialists at both firms estimated the likely hammer price for each object in the sale. This analysis, sometimes referred to as the “will make” process, is essential to setting an acceptable guarantee level.

Creating “will makes” for more than five hundred objects is time consuming. The end product is a spreadsheet with a low, midpoint, and high hammer-price estimates for each object based on specialist input. Senior management then use the spreadsheet to make decisions on different guarantee levels—high enough to win the business but low enough to make money on the sale.

The Taubman family, being especially astute observers of how auction houses work, understood clearly the competitive needs of Sotheby’s and Christie’s and the process they were going through to determine acceptable guarantee levels. The family probably felt that if the two houses devolved to similar guarantee deals during the back-and-forth negotiating process, then Sotheby’s would probably be willing to up its bid at the very end of the process to win it.

No one was surprised when Sotheby’s announced in early September that it was selling the Taubman Collection, but the art world was shocked by the size of the guarantee. Rumors passed that Sotheby’s guarantee was $50 million higher than Christie’s “walk away” guarantee amount. The higher amount probably had less to do with Sotheby’s specialists believing they could sell the collection for higher prices than Christie’s, and more from a conviction they had to win the business at any cost.

How did Sotheby’s market the collection to potential buyers? Sotheby’s executed a thorough and exacting marketing plan so that every potential buyer, anywhere in the world, knew about the Taubman sale. From elaborate catalogues, to special pop-up exhibitions of property in different cities around the world, to videos highlighting works from the collection, Sotheby’s pulled out all the stops to make the Taubman sale a success.

When did financial markets realize that Sotheby’s had a problem? When Sotheby’s announced on September 3 that it won the Taubman estate, it did not impact the company’s stock price. Between the announcement date and the end of October, Sotheby’s stock price remained largely unchanged, trailing somewhat the performance of the S&P 500 over the same period. But in early November, the combination of weak sale results from the first Taubman sale and Sotheby’s announcement that it would at best only cover the guarantee amount led to significant downward pressure on the stock. By the end of November, the stock was down almost 17 percent relative to the beginning of September. Poor results from additional Taubman sales, plus early signs of a weakening in the overall art market, continued to weigh heavily on the stock. By the end of the year, Sotheby’s stock price had fallen 24.3 percent from September 1, while the S&P 500 was up 6.3 percent over the same period.