In March 1845, Henry David Thoreau left the New England town of Concord and set out for the woods around Walden Pond and, having borrowed an axe for the purpose, began to cut down white pines on land owned by his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson. As Thoreau shaped the timbers, he stopped to eat his lunch of bread and butter, reading the newspaper in which it was wrapped. He was constructing a hut, an unfixed locality, citing Indian teepees as eminently suitable to their purpose and eschewing the mortgages to which his fellow Concordians were shackled. The philosopher hoped for a reconnection, albeit a temporary one. ‘We no longer camp as for a night,’ he wrote, ‘but have settled down on earth and forgotten heaven.’ He sought utopia by the water’s edge, just as William Blake, after ‘three years’ slumber on the banks of the Ocean’ in his Sussex cottage, had proposed a new Jerusalem.

The son of a pencil-maker, Thoreau was educated at Harvard University, and had briefly been a teacher – he gave it up after finding corporal punishment an offence to his sensibilities. In 1842 his twenty-six-year-old brother had died in his arms, from lockjaw caught after cutting himself shaving. Thoreau was consumed with grief. He later proposed marriage to a young woman, and was rejected. Thereafter he would work as a surveyor, measuring out the land while pondering its metaphysics. Now he had retreated to a New England wood (the same wood he and his friend Edward Hoar had managed to set on fire when camping there the previous year). Even in his attempt to distil utopia into a commune of only one, Thoreau could not help but be part of the greater world. When he bought the frame of his shanty from an Irish navvy – for four dollars and a quarter – there was another price to be paid: by the family effectively evicted by the transaction, and by their cat, which went feral and was killed when it trod in a trap laid for woodchucks.

By the sandy shores of Walden, in among its trees, Thoreau unpacked his shack and trundled it, bit by bit, by cart to his pondside site, laying out the parts to dry and bleach in the sun (having been told by ‘a young Patrick’ that another Irishman had already stolen all the nails). He excavated a cellar underneath the hut where he could overwinter his potatoes; all houses, he wrote, were ‘but a sort of porch at the entrance of a burrow’. He was digging into the land like a badger.

Friends helped him raise the frame of his house, in the way Shaker barns were raised as communal efforts, and he took possession on the Fourth of July. Construction continued as he built his chimney using stones from the pond, claiming them, as he did the timber, under squatter’s rights. Thoreau relished labour for its own sake. If we all built our own houses, he said, ‘the poetic faculty would be universally developed, as birds universally sing when they are so engaged’. Instead, ‘we do like the cowbirds and cuckoos, which lay their eggs in nests which other birds have built’.

Thoreau saw transcendence in everything he did and wove philosophy out of the commonplace. He lived in his own quietude, finding it more fruitful than the alternative. ‘The man I meet,’ he said, ‘is seldom so instructive as the silence he breaks.’ Made insular by the beauty of the natural world, he wrote about himself, reasoning that ‘I should not talk so much about myself if there were any body else whom I knew as well.’ And if he lived in a dream, what of it? What else should we do with our hours of wakefulness? Nothing more useful than the hours we spend dreaming.

Shingled and plastered, ten foot wide by fifteen foot long, with eight-foot-high posts, Thoreau’s hut contained an attic and a closet, a tiny cellar with two trapdoors, and a brick fireplace. Outside was a woodshed. All built by himself, for $28.12½, including $1.40 transportation (‘I carried a good part on my back’). He reckoned the price to be less than the annual rent paid by most of his townsfellows, another good reason to recommend the effort. ‘I brag for humanity rather than for myself.’

Walden Pond is wonderfully cold on a late spring afternoon. I push out from shore, reluctant to go far, knowing Thoreau’s plumbline drew more than one hundred feet as he surveyed its dark extent. In midsummer this place is alive with people and noise, with children and picnics and canoes. Today, it is silent and still, save for the concentric rings sent out by my body. It’s hard to believe that Boston is only half an hour away. The railway runs close by; it did so in Thoreau’s day, although the whistling trains merely reminded him of his solitude. On the other side of the road there’s a replica of his hut, complete with a bunk covered with a green woollen blanket; a single bed is as eloquent as any obituary, or any passing star. ‘Why should I feel lonely? is not our planet in the Milky Way?’ reasoned its sole occupant. ‘We are wont to imagine rare and delectable places in some remote and more celestial corner of the system … I discovered that my house actually had its site in such a withdrawn, but forever new and unprofaned, part of the universe.’

Thoreau’s daily swims were a communion, undertaken at dawn. ‘I got up early and bathed in the pond; that was a religious exercise, and one of the best things I did … Morning brings back the heroic ages.’ Ever analytical, he tried to examine the very colour of the water – ‘lying between the earth and the heavens, it partakes of the color of both’ – and noted that a glassful held up to the light was crystal clear. And in a dreamlike image, he observed that when the body of a bather – presumably his own – was seen through the water, it was ‘of an alabaster whiteness’, the limbs ‘magnified and distorted withal’. Nowadays analysis of the pond water in summer betrays a high volume of human urine.

Walden Pond became an extension of Thoreau’s hut; he even used its white sand to scrub his floor, wetting and scattering it before brushing it clean. Were all these activities, so exactingly and intensely enumerated, ways of forestalling darker thoughts? The black water offered liberation. ‘After hoeing, or perhaps reading and writing, in the forenoon, I usually bathed again in the pond, swimming across one of its coves for a stint, and washed the dust of labor from my person, or smoothed out the last wrinkle which study had made, and for the afternoon was absolutely free.’

In nearby Concord, after swimming in the clear green weedy river behind Nathaniel Hawthorne’s house, hoping he wouldn’t mind, I visit the basement of the town library, where the curator emerges from the vaults with an armful of oversized documents protected by plastic sleeves. They flap rather worryingly in her hands as she lays them out on the table with a mixture of reverence and familiarity. I am allowed to inspect, but not photograph these relics, prophylactically sheathed in mylar. The air has been sucked out of them; the human has been excluded. Seen through thin plastic they remain remote, even though they’re lying in front of me.

Thoreau’s fine draughtsmanship charts the pond as carefully as a navigator might chart the sea; as his plumbline drew water, so Thoreau drew the pond. Tiny numerals record the depths – 30', 91', 121' – and ruled lines divide its expanse in precise, faint ink, as though he had trailed a sepia fishing rod behind him as he rowed across the pond. Thoreau may have sought to disprove those who believed Walden to be bottomless, but in the figures an implicit poetry seeps out; mere mathematics could not confine his thoughts. These points could be constellations as much as charts of a body of water. To him, ‘there was no such thing as size’, his friend Emerson wrote. ‘The pond was a small ocean; the Atlantic, a large Walden Pond. He referred every minute fact to cosmical laws.’ Walden was a microcosm of everything. ‘It is earth’s eye,’ Thoreau said, ‘looking into which the beholder measures the depth of his own nature.’ Yet in imposing his lines on the wilderness, wasn’t he destroying what he observed, even as he’d managed to burn three hundred acres of it by mistake?

In a tall glass case against a pillar that supports the silent mass of books upstairs – who reads them now? Certainly not the people sitting at the tables, their faces turned pale by their laptops – Thoreau’s instruments are displayed. The polished wooden tripod and theodolite mark the measure of the man, as if he’d just stepped away to take account of the land around, taking in all that beauty and not believing it.

In 1862, as he lay in a Concord attic, dying of the disease that consumed him at the age of forty-four, Thoreau edited his final text, ‘Walking’. It’s here, on the table. I copy the words from his own hand, closing the gap between his then and my now. It is his last will and testament, by default: ‘I wish this evening’ – the two words excised in the edit for posterity’s sake – ‘to speak a word for Nature, for absolute freedom and wildness, as contrasted with a freedom and a culture merely civil, – to regard man as an inhabitant or a part and parcel of Nature, rather than a member of society.’

New England lay empty and full of history, settled and unsettling; it allowed such transformations for its utopians and its Transcendentalists. Emerson had experienced a panoptic epiphany on Boston Common: ‘Standing on the bare ground, – my head bathed by the blithe air and uplifted into infinite space, – all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eyeball; I am nothing; I see all.’ Other peers of Thoreau took matters to an extreme. Samuel Larned was the son of a Providence merchant who had become obsessed with his own consumption. He’d spent a year living only on crackers; the next year devoted to eating only apples. When he stayed at Brook Farm he declined to drink milk and wore vegan shoes. He also swore at everyone he met: ‘Good-morning, damn you.’ We might diagnose Tourette’s syndrome, but Larned believed that profanities uttered in a pure spirit ‘could be redeemed from vulgarity’.

Larned and his young friends were the Apostles of the Newness, marked out by their ‘long hair, Byronic collars, flowing ties, and eccentric habits and manners’. In 1842, three of them set off on a walking tour, wearing broad-brimmed hats, sack coats and as-yet unconventional beards. They took no money with them, relying on people they met to provide them with food, although, as Richard Francis comments, ‘given their severe dietary restrictions, that wasn’t asking much’. When they arrived at Emerson’s house, he quickly moved them round to the back door where their swearing wouldn’t disturb the neighbours. Their appearance was becoming more outrageous: by the time Larned and his friends came visiting the following year, they were ‘peculiarly costumed’ in smocks belted about the waist and made of ‘gay-coloured chintz’.

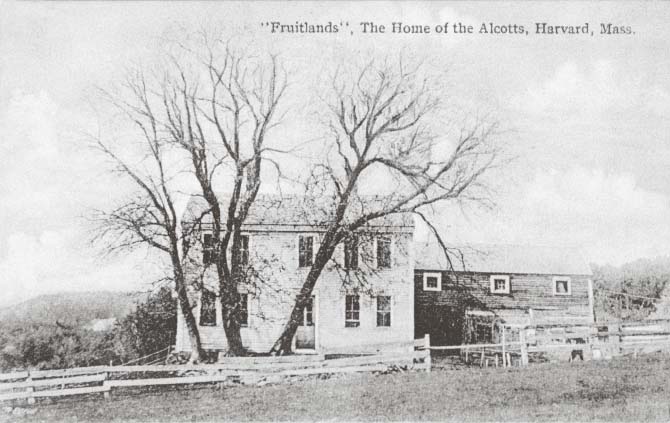

The sight of these visionary young men dressed in what looked like blouses got up from flowery curtains must have made a certain impression in the streets of Concord and Boston, as similarly dressed young men would do in Woodstock the following century. Even at the time they were referred to as ‘ultra’, as if set beyond the pale. That year, 1843, Larned found his natural home in the nearby commune of Fruitlands, whose members declined to enslave animals to plough their fields and used, ate or wore nothing animal or produced by slavery, from cotton to whale oil. Some went naked under the New England sun, while their leader, Bronson Alcott, bathed in cold water, rubbing his body afterwards with a ‘friction brush’. He also claimed to be able to enter a kind of altered state, with sparks flying from his skin and flames shooting from his fingertips, ‘which seemed erect and blazing with phosphoric light’, as if he were a Blakean being. When he closed his eyes, they ‘shot sparkles’, and in his ears he heard a melody, ‘as of the sound of many waters’.

In contrast to these urgent eruptions around him, Thoreau’s was a quieter resistance – for all that he practised civil disobedience and even went to prison for one night as a protest against his taxes being used to support war and slavery. If he was said to be an ugly man, he became beautiful by virtue of what he observed and absorbed. ‘I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life …’ He too discovered slowness, seeking meaningful leisure ‘for true integrity’, free of property and employment. At Walden, he found the earth’s eye. And as he looked into the water, he saw the rest of us too. His last words, knowing he was about to die, were ‘Now comes good sailing.’

Exiled on the island of Crete, Daedalus was imprisoned by the waves and determined to escape. The only way was up. The architect made wings from feathers fastened with wax, hindered in his work by his playful young son. As they set off on their timeless flight, Daedalus told Icarus to ignore Orion the Hunter and be guided only by his father. He must not get too close to the sun or the sea; either would be disastrous.

They took off into the air, watched by fishermen and shepherds who thought they must be seeing flying gods. But Icarus could not resist going higher; perhaps he wanted to be a god himself. Rising high in his ecstasy, he left his father far behind and soared up towards the sun. As his wings melted, his dreams came apart and the boy tumbled into the sea. His father called for his son in vain. Then he saw the feathers on the waves, and cursed his own invention.

Something falls out of the sky and into a lake. There’s a burst of white against the blue. His coming is seemingly unnoticed by the rest of the world. He wanders into a one-horse town; the landscape is as arid as the place from which he came. He looks like a comet, his flame-like hair slicked back on entry into the earth’s atmosphere. Even stumbling down what appears to be an enormous cinder pile he is otherworldly, a pale bird of paradise picking his way through blackened coals. As the visitor exchanges his grey overalls for a plain black suit, he assumes a worldly guise and an ordinary name and proceeds to build a secretive corporation, World Enterprises, producing inventions from instant cameras to electronically generated music.

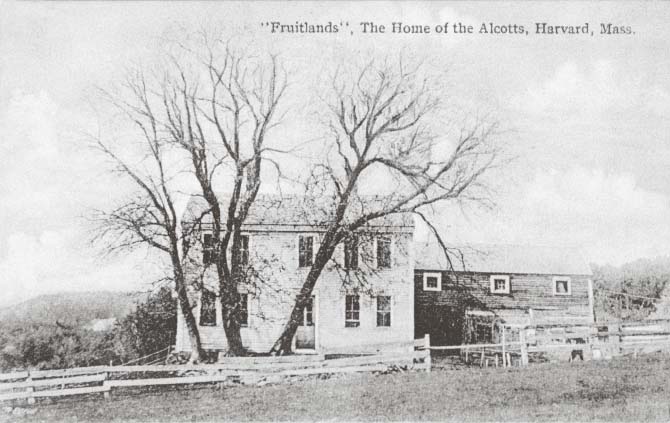

A lavish art book lands on the desk of a university professor, Nathan Bryce. It is published by WE and entitled Masterpieces in Paint and Poetry. It falls open – to a burst of seagulls on the soundtrack – revealing Brueghel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus.

A mere splash of a boy, all kinked knees, plunges into the corner of a world going about its business. A ploughman’s red shirt draws the eye to the centre of the picture; a ship sails on a Renaissance sea. On the facing page are Auden’s lines:

… the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

All these scenes seem to refer to something else before and after, as if, like Orlando, the story was running backwards and forwards in time. As Mary-Lou the hotel maid shows Thomas Jerome Newton to his room, he collapses in the lift. She has to pick him up in her arms – as thin as he is – carrying him down the corridor, his nose bleeding, head lolling and legs dangling like a pietà. The next day she and Newton go to church, where they sing ‘Jerusalem’ – And did those feet, in ancient time, walk upon England’s mountains green.

Newton is oddly innocent, both in and out of control, invincible and vulnerable, wide-eyed at the world yet knowing it all. He is a Prospero arriving on island Earth; a refugee from Anthea, his planet from which the sea has disappeared. He is also an omen, a saviour and a sacrifice: seeking to save his own home and warning us of the danger to ours. He might as well walk on water; even his centre-parted hair is reminiscent of Jesus. In the novel by Walter Tevis on which the film is based, the comparison is more obvious. When he sees a painting of Christ on the cross, Newton is startled – ‘with its thinness and large piercing eyes it could have been the face of an Anthean’ – and when Bryce wonders if there will be a second coming, the alien replies, ‘I imagine he’ll remember what happened to him the last time.’

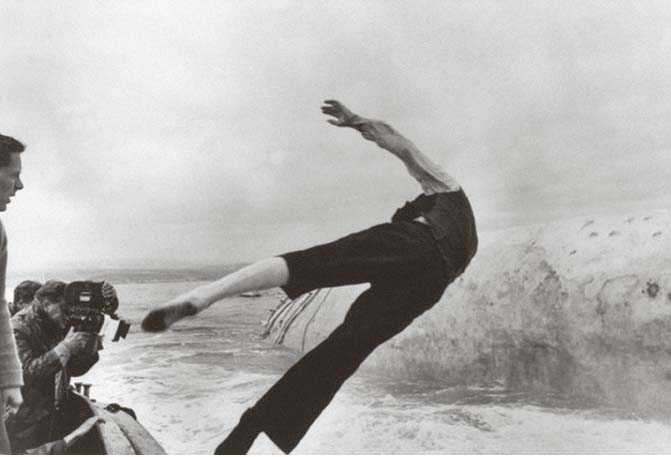

The way he inhabits the film is unsettling. His performance has an interior, kabuki air – perhaps because he had been trained in mime by a man who had felt ‘confronted by this vision of the beautiful archangel Gabriel, glowing, shining’ (among the star’s improvisations were sailors drowning at sea and animals hunting their prey; he and his tutor-lover, Lindsay Kemp, also planned to make a musical of The Water-Babies together, just as two years later, Derek Jarman wanted him to sing Ariel’s songs in his film of The Tempest). On location he kept to his trailer, behind its wooden blinds, declining to mix with the rest of the cast; he told his director, Nicolas Roeg, that he wanted to play Newton as a recluse like Howard Hughes, although he also became addicted to eating ice cream, a habit that had to be curtailed since he started to put on weight, which may explain the corset he wears in later scenes.

Tevis describes his character’s bones as bird-like; when he is driven about, Newton tells his chauffeur, Arthur, to slow down and keep to thirty because he is unused to earth’s gravity. And in an operation in which he reveals what appears to be his true self, he pulls off prosthetic nipples and penis and takes out his lenses to reveal yellow eyes with vertical slits, like some creature looking out over the veldt. It is another mask. All the time, we are aware that the real person behind those blue eyes – which were in reality odd enough, one permanently dilated pupil ringed with bird-like intensity after a boyhood fight – was a transformer who had moved through animal as well as human guises. Most lately he had become half-canine, half-human, a dog star, dangling a diamond earring and singing with a feral yelp, prowling a post-apocalyptic city whose skeletal wreckage prophesied the future ruins of other towers. Like the wolfish Virginia’s vision of Vita as a porpoise or a stag, he was fabulous in the true sense of the word, since fables are our fates as embodied by animals.

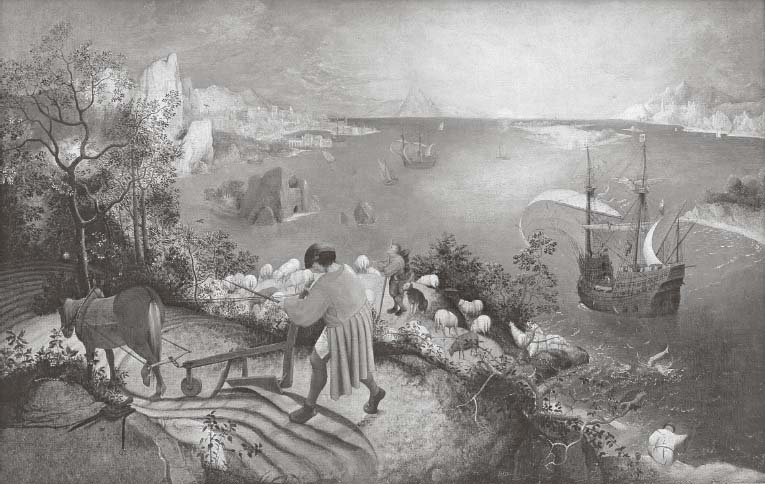

To me, he became another creature too. Looking out over the lake where he fell to earth, Newton sees his desert planet and his family walking through endless dunes where the sea had been but was no more. He dreams of aerial oceans, and in a sequence which I only registered subliminally then, he and his Anthean wife spin around one another in a fluid cybersexual space while we hear snatches of whale song and ‘oceanic sounds’ supplied, as the credits now reveal, by Woods Hole Oceanographic Centre, Cape Cod, and recorded by Frank Watlington.

During the nineteen-fifties, Watlington had been working for a secret American base on Bermuda, where he devised an underwater microphone to listen for Russian submarines, in much the same way that astronomers would listen for signs of extraterrestrial life. From his hydrophone fifteen hundred feet deep in the Atlantic, he recorded the songs of humpback whales for the first time. Watlington had kept his discovery secret for fear it would be used by whale-hunters. But in 1967 he drew it to the attention of a biologist, Roger Payne, and his wife Kathy, who together with the scientist Scott McVay realised there was a repeating pattern to the strange noises off the island that had inspired The Tempest. The Paynes began to record the songs for themselves from their yacht, Twilight. ‘Far from land, with a faint breeze and a full moon, we heard these lovely sounds pouring out of the sea.’

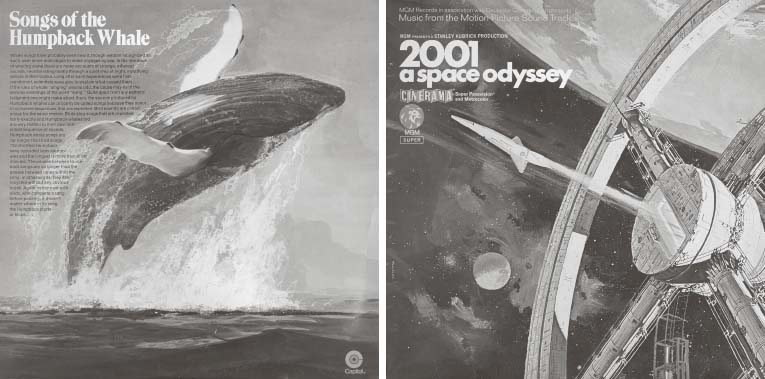

In 1970, Roger Payne released Songs of the Humpback Whale. The future had been announced – not from beyond the earth, but beneath its seas. The blue-toned album cover, showing a whale breaching out of the ocean, echoed another soundtrack – 2001: A Space Odyssey, released two years earlier, displaying a spacecraft shooting from its mother ship like a slender cetacean. Payne’s hydrophone recorded an animal out of time and space. We were looking for aliens beyond our galaxy, when all the while they were living in our oceans. Even their binomial, Megaptera novaeangliae – big-winged New Englanders – invoked a new age. We’d seen our blue planet from outer space and realised that there was nothing we could do. When Newton tells Bryce, ‘Our word for your planet means “planet of water”,’ he is citing Arthur C. Clarke, the author of 2001, who thought the Earth would be better named the Ocean.

In 1972, an atomic-orange poster for a concert to save the whales showed the starman as a space-age Ariel astride a grenade harpoon, superseding its barbaric cruelty with his lamé and lurex. Around the same time, I saw my first whale: a stolen animal in an inland pool, the same graphic orca that would leap out of my notebook. It too was a sign, although I didn’t understand it. It wasn’t until 2001, shortly before the aeroplanes dropped out of the sky, that I saw another whale, launching itself off Cape Cod like the rockets which had blasted off from Cape Canaveral in the seventies, sending probes spinning into the solar system – lonely voyagers loaded with whale song on golden discs for aliens to hear, just as John Dee used his golden disc to communicate with angels, and just as Kubrick’s film hums with another alien sound, emitted from a mysterious black monolith. Like The Tempest, 2001 is filled with classical references and performed in formal language as a masque, a ritual moving languidly from the dawn of man, via titanium-white spaceships, to the end of time.

It is also, as Andrew Delbanco observes, a very Melvillean film. The astronaut, David Bowman – his name oddly close to that of the performer who would be inspired by the film to write a song that set him adrift – resembles a beautiful version of an American football player as he lies under a sunlamp in his white shorts. Space pods float like bathyscaphes; they might as well be sinking in the benthic ocean, crewed by deep-sea divers. Later, Bowman’s mate, the orange-suited Frank Poole, is lost in fathomless space, spinning into infinity.

Bowman, strangely distanced from the drama into which he is plunged, is a twenty-first-century Ishmael caught up in an unknown mission; not for a white whale, but for a black slab. Indeed, a generation before, just before I was born, John Huston had come to Britain to film Moby-Dick, his nineteen-fifties version of Melville’s science-fiction search for a grand hooded phantom swimming in a black ocean, spanning time and space, tugging Ahab out of his boat and into the infinite sea.

All these things seem so fated, from this distance and this close, that I’m not surprised to find that all three alien creations – black monolith, fallen angel, white whale – were filmed in the same studios outside London, born in a sort of suburbia, out of imaginations contained behind tree-lined avenues.

I first saw Kubrick’s film in a small cinema in Southampton’s nineteen-seventies high street, barely recovered from its wartime blitz. The narrow building, more accustomed to showing Swedish porn, was slotted between a shoe shop and a bank; a secret place down a dark lobby, more like a nightclub.

I entered as if I knew I were doing wrong.

Two hours later I emerged dazed from the hallucinogenic ending – the astronaut’s blue eyes staring and shaking as they witnessed the making and unmaking of worlds, blinking in a white room like a giant microscopic slide where he lay as an old man, wondering if that was the way to die, only to become a star-child in a caul, floating far above the earth.

What remained with me, and still does, is the deepness of these worlds – the spaceship, the alien, the whale – only waiting to confirm our future. Whiteness was its aesthetic, an appalling pallor, a plastic dystopia fabricated from petrochemical products that were already starting to poison us. Now, fifteen years after the passing of the year it commemorated, the slowness of Kubrick’s film and its sparse words seem more Jacobean drama than modern movie; a Cinerama version of Prospero’s story, with its Caliban apes (led by Dan Richter, a Provincetowner), its computerised Ariel, Hal, and its brave new world. These moving images barely move at all; continually showing in a loop in some decrepit cinema since I first saw them, they are mechanical, needing and creating light, dreams burned into and out of their celluloid.

How small the past looks from the future; even yesterday seems old-fashioned compared to tomorrow, and the day after that. In my Provincetown attic, as the sun sets over the bay, I re-view Roeg’s film, which I first saw forty years ago, watching it on my white computer, which might have been made by World Enterprises. Newton, wearing a suit of long underwear and a grey buckled corset to keep his bird bones intact, sits in front of a bank of televisions. This is the way he has learned about the earth back on his planet, picking up the incontinent transmissions of the human race as they leak out into space, sampling images to be watched by aliens as if through compound eyes. It was the same way I’d learned about the world, too, from the TV in the corner of our front room. Then, machines were the future. Now, the space station slides across our suburban skies, night after night.

Each flickering cathode-ray tube, tuning in and out of Newton’s array, broadcasts its own footage: an Elvis movie, lions mating, a NASA rocket launch. But in a cut-up worthy of Burroughs or Paolozzi, there’s one black-and-white scene that causes me to pause the film, something I could once have done only in my head. It’s as though the director-magician has inserted it retrospectively for my attention. With the dark sea roaring outside, it seems to have been conjured up out of my wishful thinking.

For a moment I wonder if I’ve imagined the whole thing. I rerun it, rerunning time, and watch it again.

In snatched clips we see a young Terence Stamp, an Adonis with bleached blond hair playing Billy Budd, the Handsome Sailor, in a sequence taken from the 1962 film of Melville’s novella. (The director cannot say why, he later tells me in a London basement.) Betrayed by Claggart, the punitive master-at-arms whom he has accidentally killed, the angelic Billy is about to die. Captain Vere declares solemnly, ‘If you have nothing to say, the sentence of the court will be carried out’ – and we see the sailor with the rope around his neck crying, ‘God bless Captain Vere.’ As Billy’s body is about to be consigned to the deep, the crazy images collide and Newton responds in panic as if he’d seen his own future, ‘Get out of my mind, all of you!’

That summer of 1976, I left school. The days extended, ever hotter, falling on their knees. Southern England became a landscape devoid of water. The port city where I lived registered the highest temperature in the country. The grass burned and the earth baked, great cracks opening up as if to swallow me. If I’d thought about my future at all, I would have felt sorry for the boy I was rather than the person I would become. I wore my sunglasses and my jumble-sale clothes as a collage of all the people I wanted to be, gathered from the dead of a generation whose belongings were being disposed of in scout halls. I felt the texture of the past, recycling history that had never happened to me, looking forward to a foreshortened future. I lived in another time, another place. I don’t suppose it occurred to me that the national emergency – when the rain failed to fall, reservoirs dried up, fires raged over heaths and crops withered – was a sign of things to come. We waited for some change in the weather. Newton’s dry planet was my own. Water had acquired a new meaning, but I had no idea. I couldn’t swim.

At the beginning of the year I’d stood on a railway platform dressed in white school shirt, salvaged black evening waistcoat, trousers with satin seams and cracked patent shoes, my hair slicked back and sprayed gold, waiting to be conducted to a pitch-black arena where Kraftwerk’s crackling ‘Radioactivity’ and the brutality of Un Chien Andalou, in which an eye is sliced open with a razor, gave way to the sound of a relentless engine and the sight of the man himself, improbably teleported to an earthly stage, sunken-cheeked, too thin to be contained by the fluorescent cage of striplights thrown around him.

He’d arrived from Dover in a slam-door train, to be driven from the station in an open-top car like someone to rule us. In a bankrupt, blacked-out country with the power cut off and insurrection threatening, the whiteness of 2001 seemed far away. I felt I had been summoned to his presence, to the future. He was in a new incarnation, a self-portrait seen in a dark glass. There he was, dressed in black and white, a pack of Gitanes in his waistcoat pocket, a Prospero throwing darts in lovers’ eyes as he quoted from The Tempest, singing of the stuff from which dreams are woven; bending sound, dredging the ocean, lost in his circle. I was alone with him in the darkness, overlooking that ocean. The cavernous auditorium in which he performed his apocalyptic cabaret was built as a swimming pool for the 1934 British Empire Games, two years before other games were conducted in another European capital – cities connected by that same railway, that same past and future, that same deathly glamour. I had no idea that his opening song was inspired not by trains but by the Stations of the Cross; although I always noticed the two crucifixes around his neck.

We were separated by the sea: the Pacific he overlooked from his room and the Atlantic he crossed in white liners; New York and California, Hockney’s pools and Max’s Kansas City; white boys in peg-top trousers and dyed hair and chic black girls with peroxide crops. Stranded on a south-coast estuary, mine was a world of wood-trimmed trains and slow-moving cars and suburban streets which still seemed to operate under the shadow of rationing. He gave me a dark glittering world, his monochrome figure held against the moonlight, mime-walking as if caught in a loop, marking time. We’d come from the same place; I was physically like him; yet in that flashlit year of transition he had been transformed anew, by the same alchemical process which had burned his hair.

Gods require us to believe in them; they wouldn’t exist otherwise. Seeing him in the flesh was as disconcerting as the killer whale in a suburban pool. I needed to close that distance. I wanted to feel the high collar of his white shirt against my neck; the tailoring of his waistcoat around my ribs; to look normal, like him, and yet utterly different, like him. I came out that evening carrying the tour programme, ISOLAR, a cross between a newspaper and a secret manual, its cover with his back turned on us like a priest. I looked for every coded detail in its pin-ups set alongside inexplicable radioactive images of his forefinger and a crucifix and a photograph of him in dark clothes daubed in diagonal stripes of white paint from his slash-necked top to his rolled-up trousers (taken in at the waist to fit his shrunken frame) down to his socks. He stands straight, arms by his side, looking to the horizon, disturbing it like a dazzle ship, moving in and out of register like a mistuned television. Even in yellowing newsprint he’s still performing, stripped down to a DIY aesthetic, as if he was a teenager like me, dressing up in front of his bedroom mirror.

And as my first year of adulthood began with witnessing him on stage, it ended with seeing him on film, more remote as he became more intimate. In the sex scenes, his hairless body is both elegant and awkward; he appears hermaphroditic, both animal and disembodied, as if his lower half had always belonged to a dog or a deer. His pale face was his fate, and mine.

Now living by the lake where he first appeared, Newton comes to Bryce one evening, appearing at the end of a jetty: an ashen, hooded doppelganger in a duffel coat, looming out of the darkness like a ghostly monk.

‘Don’t be suspicious, Dr Bryce,’ he says, before disappearing back into the night.

In the chapter in Tevis’s book which inspired this scene, Bryce walks around the lake towards his employer’s house, a white nineteenth-century clapboard mansion, and stops to stare at the water. ‘He felt momentarily like Henry Thoreau, and smiled at himself for the feeling. Most men lead lives of quiet desperation.’ Bryce sees Newton walking towards him, wearing a white short-sleeved shirt and grey slacks. As he draws steadily nearer, the alien’s otherness is made manifest. ‘There was an indefinable strangeness about his way of walking, a quality that reminded Bryce of the first homosexual he had ever seen, back when he had been too young to know what a homosexual was. Newton did not walk like that; but then he walked like no one else; light and heavy at the same time.’ He seems to move as if through water.

The two men sit and drink wine. Bryce wonders whether Newton is from Mars or Massachusetts, and he thinks of the migration of birds, ‘following old, old pathways to ancient homes and new deaths’. He’s worried that the spaceship he is helping Newton construct may be a weapon. Newton asks Bryce if nuclear war, which caused his own planet’s devastation, is imminent (Tevis’s book was published in 1963, a year after the Cuban missile crisis). All the while, as the film makes clear, dark forces are marshalling against the stranger in a country once settled by visitors but which now sees them as a threat. ‘This is modern America,’ they murmur, ‘and we’re going to keep it that way.’

Bryce returns to his house drunk, and peers at a reproduction of The Fall of Icarus on his kitchen wall (Sylvia Plath had the same picture hanging in her apartment). He sees ‘the sky-fallen boy’ who ‘burned and drowned’, and wonders if Daedalus’ invention was where it all went wrong. In the film, Newton stands by a blue light on his jetty overlooking the lake, his incandescent locks and pale profile held against the water, later to reappear on another nuclear-orange cover. He’s an Ishmael or a Gatsby, sensitised to psychic disturbances in the way that Scott Fitzgerald’s mysteriously wealthy anti-hero is ‘related to one of those intricate machines that register earthquakes ten thousand miles away’.

And in a sequence which plays and replays over and over in my head, Newton is being driven through the backwoods when he sees a group of early settlers in sepia, as if his vision had become doglike, as if he were seeing through a filmy continuum. He looks out; they look back, amazed to see, not a boy falling from the sky, but a car driving past. And we see it all in the way we see scenes from a train, as Virginia Woolf wrote, ‘as a traveller, even though he is half asleep, knows, looking out of the train window, that he must look now, for he will never see that town, or that mule-cart, or that woman at work in the fields, again’.

‘I’m not a scientist,’ Newton tells Bryce. ‘But I know all things begin and end in eternity.’ It was another reference, as Roeg would reveal, to William Blake, who saw angelic figures walking among the haymakers in Peckham Rye and trees filled with angels as if caught in the branches, and wrote, ‘Eternity exists, and all things in eternity Independent of Creation which was an act of Mercy.’ And I think of Blake’s image of another Newton: the alchemist-scientist sitting at the bottom of the sea, futilely measuring out infinity. Centuries before – although it might have been hundreds of years ahead – another magician, Prospero, asked Miranda, ‘What seest thou else | In the dark backward and abysm of time?’ That year, recording in a French château, the star asked his producer what a particular piece of studio hardware was for. He was told, ‘It fucks with the fabric of time.’

He scared and excited me. I wanted to be him, not to have him. He represented freedom and danger. He was absolute artifice, but utterly feral too: nothing could be so exciting or so challenging. He had only to walk into an Amsterdam hotel to appear completely otherworldly; wherever he appeared, he was the focus of disruption, a disturbance in the ether. He was my dark star. He had summoned me to the city. A year which began for me watching the television in the suburbs – the same screen through which I first saw him, posturing as a corrupt, tinselled Nijinsky, pawing at his guitarist like some predatory animal – ended in my descent into a real nightclub. I slammed the train door and crossed the river, a brown god by day, a black serpent by night, and walked down a dark street surrounded by empty-eyed warehouses to stand in a queue where a boy in a biker jacket with spiky bleached hair asked me for a light.

As the flame sparked in his face he became another Ariel. We were children of a man stealing time who told us that nothing could help us and who, having visited an oceanarium, as his friend dimly recalls, wished he could swim like a dolphin, like the dolphin he would have tattooed on his skin.

When Songs of the Humpback Whale was released, some people believed they were listening to the voices of aliens. In Walter Tevis’s novel, the description of the recording of Newton reading his poetry in Anthean might as well be an account of whale song, ‘sad, liquid, long-vowelled, rising and falling strangely in pitch, completely unintelligible’. In the book, Newton – who, it is now clear, came to rescue humanity from nuclear and environmental destruction – is blinded by the inept scientific examinations of the authorities, ‘certainly not the first means of possible salvation to get the official treatment’. The alien admits to being afraid of ‘this monstrous, beautiful, terrifying planet with all its strange creatures and its abundant water, and all of its human people’. In the film, Newton is released by the mysterious agency from his apartment-prison, with its rococo wallpaper depicting those same uncanny beasts. In the last scene, set in some future Christmas, we see him – his herringbone coat over his shoulders, his burnt-out eyes shielded by sunglasses, his flaming hair held under a fedora like the ghost of Christmas past and yet to come – drinking in an outdoor bar.

There he is tracked down by Bryce, now an old man. Only the alien remains the same; the rest have aged around him, although he has become human, like us. He has released, anonymously, a grey-sleeved album, The Visitor (when Bryce buys it in the supermarket, we see the colourful cover of Young Americans displayed behind him). As they talk, Newton toys with his drink – his thirst having become an addiction, binding him to earth – and he tells Bryce that his recording has a message for his wife which he hopes she will hear when it is played on the radio, broadcast like whale song, to be picked up back on his home planet. But as he looks up from the table to a helicopter whirring overhead, it is clear that the grounded angel will never be set free; that he will always be under surveillance, like the rest of us.

When interviewed about this time, the star said his work was about the sadness he felt in the world. Perhaps that was why, in some performances on his tour, he appeared with a thin gold veil over his face, denying the gaze of thousands of eyes. A veil to stifle as well as conceal. It was a strangely silent age, for all its noise. Sound had to be physically summoned through a needle or read from magnetic tape.

There was something about this breakpoint, three-quarters of the way through the century, the year in which I turned eighteen. There seemed to be a disturbance in history, the result of accelerating time; the threat of a disrupted country and an overturned world, the threat of violence and extinction, the last point at which the planet was still sustainable; the shift from the twentieth century towards the twenty-first that exposed things between the cracks.

When filming in New Mexico – like New England, a place cleansed of its first peoples – the production used locations which included a Mesoamerican graveyard, from which the actor – who was now living on milk, red peppers and cocaine – insisted on having his trailer moved. Meanwhile the crew reported malfunctioning cameras, an echo of Bryce’s attempt to covertly film his employer using a World Enterprises x-ray camera, only to find that the resulting image showed an empty body.

Throughout this period of flux the star felt haunted by the personae he had created. Beset by a metaphysical terror, himself an exile in America, he consorted with the supernatural, drawing pentacles in chalk and burning black candles, discerning the shape of the devil in his swimming pool and believing that bodies were falling past his window in Los Angeles – a city of lost angels – just as in the film’s most horrifying sequence, Newton’s gay lawyer, Oliver Farnsworth, is thrown through his own apartment window by secret agents. The men pick up Farnsworth by his arms and legs, swinging him at the plate glass, but his body bounces back and he apologises to his assassins, one of whom replies, ‘Oh, don’t worry about it.’

Now at college in an eighteenth-century gothic building, exiled in a London suburb – neither part of the city nor my home – I went to see the film over and over again, as if I were going to Mass rather than the movies. I did not know then that it had been made in studios only a few miles down the road. I walked to the local cinema along the river that followed me down Cross Deep, ignoring its wide green waters that ran under drooping willows. I had no interest in it, only in the nineteen-twenties building ahead, white-tiled like a temple. I took a cassette recorder from my shoulderbag and, stashing it between my feet, illicitly taped the soundtrack so that my underage sister could hear it. The tape did not come out blank, but I might as well have been recording ghosts.

That time is thick with memory. Back in my cell-like room, while my peers played on the football pitches outside, I stuck plastic cups stolen from the refectory in a grid on the wall above my bed to emulate his soundproofed capsule. I fetishised what he wore and tried to wear the same: the high-waisted quilted trousers that ended below his knees in scarlet turn-ups; the plastic sandals and seventies shirts patterned like his wallpaper; even the green visor, white shirt and belted shorts in which he plays table tennis in a room surreally decorated like a forest with autumn leaves scattered on fake-grass carpet. I dyed my hair red, using the same dye my mother used, secret silver sachets from the chemist, and wore a green woman’s jacket with padded shoulders from the nineteen-forties.

To me he represented all the weirdness of that decade which he created and which created him. I didn’t know what people were, physically; I thought then, and still think, that they were another species altogether; that it was they who were the aliens, not me. In the illusory intimacy of film, I thought I was seeing him as he was in everyday life, although what had been created was something stranger, a stranger in a strange land. His melancholy was mine. He told me so.

This is how I remember all of this; it is not necessarily how, or why, it happened, forty years ago, or forty years hence.

‘He’s just a man,’ friends tell me. He may be now, and he may have been before, but he wasn’t then.

When he was photographed for twelve hours in a Los Angeles studio, continually changing into different outfits, he might as well have turned up on Napoleon Sarony’s doorstep in Union Square with a suitcase full of costumes, as Wilde had done when he came to New York as an alien. A century later the starman would arrive on that same square, now home to Warhol’s Factory, wearing a floppy hat and long hair like an Apostle of the Newness, auditioning for another role. Or perhaps just reprising it, in the array of identities which led to that point (and then to another, and another). A few months before he had appeared on a record sleeve in a silvered ‘man dress’, reclining in a pose that referenced Wilde’s languid form draped on Sarony’s couch.

Night after night, as I came out of the cinema and into the sodium-lit street, I thought that the star – who spoke of his isolation and near madness – would walk past me, with his wide urgent stride, wearing his plastic sandals, as if he’d fallen to earth in the nearby river.

‘Surely all this is not without meaning,’ says Ishmael, as he stands looking out over the water while Manhattan rises and falls behind him. ‘And still deeper the meaning of that story of Narcissus, who because he could not grasp the tormenting, mild image he saw in the fountain, plunged into it and was drowned. But that same image we ourselves see in all rivers and oceans. It is the image of the ungraspable phantom of life; and this is the key to it all.’ ‘She had been a gloomy boy,’ Woolf wrote of her Orlando, ‘in love with death, as boys are.’ We all shudder at our earlier selves, and sigh with regret at what we did or did not put them through.

Not long ago, a museum curator led me down into the belly of the building, to the conservation studio housed in its basement. Staff were busy tending to various dummies dressed in glamorous outfits from the twentieth century, each being prepared to take its place in the galleries above. In one corner of the room a plywood capsule lay propped on trestles, like a bier. The curator lifted its curved lid and inside, under a cloud of tissue, lay a costume shaped from tarnished silver gauze; a frail, glittering suit of armour studded with sunflowers and leaves at the shoulders and hips for some Wildean parable. It had been worn in a film in which the starman played another alien, a pierrot picking his way over an irradiated beach lapped by a solarised sea. His long white stockings lay beside the outfit, rubbed with dirt.

Boxed up and ready to be launched out into the ocean, stiff on its legend and sewn over with sequins and pearls, the outfit all but trembled as I looked at it, as if an aquatic insect had emerged from its chrysalis and flown away. It might have been made of nothing. I could have reached down and touched it, this phosphorescent shroud shaped with his form, no more substantial than the glowing mantle on a gas lamp. But I couldn’t make that final connection, for fear my dreams would disappear. It was too late. The moment had passed, forty years before.

Recently I heard his voice, inadvertently, on the radio in my kitchen. It was an interview from 1976 and he was speaking as a civilian, as an ordinary person, making jokes. As I walked past, it sounded so strange and familiar, so confiding that for a moment I thought I was listening to myself.

On 10 December 1972 the starman, who declined to fly and travelled instead by sea, left New York on RMS Ellinis. On his way across the Atlantic, sitting in an overstuffed armchair in his suite, he read Vile Bodies, which opens with a stormy passage on a ship. Inspired by the book’s sense of futility and its passionate bright young things caught between the wars, he wrote a song subtitled ‘1913–1938–197–?’ I remember not wanting to acknowledge the date. On 21 December he sailed up Southampton Water, from where I watch other liners pass like glamorous ghosts in the night. I ought to have been there to greet him when he arrived, to see his peacock plume coming down the gangway, although I was only fourteen and still at school. But forty years before, on that same quayside, I might have met one of those figures from Waugh’s novel, making the same journey in reverse.

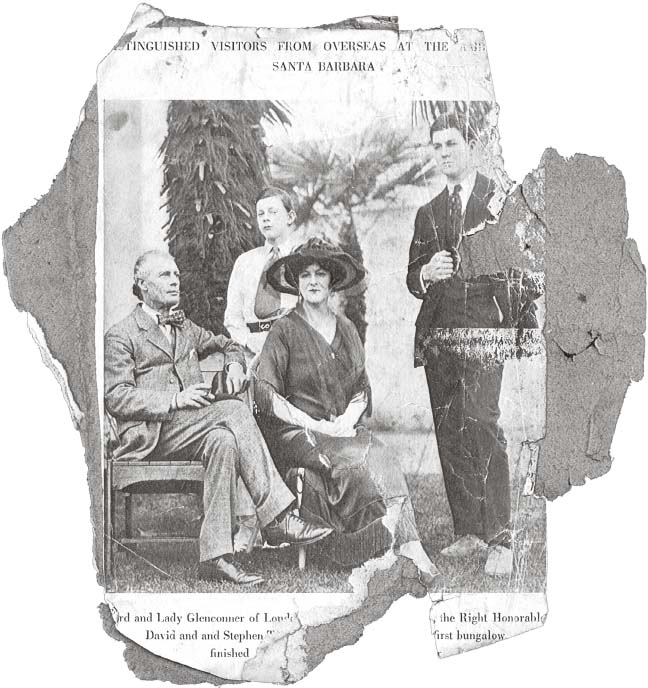

The Honourable Stephen Tennant was born far from suburbia, into a life of privilege and landed estates with intimate connections to power and influence. A magazine cutting torn from his journal shows his family on an earlier visit to America, in 1919. They had sailed from Southampton to New York, and travelled by private Pullman train to Boston, where Stephen’s mother consulted the city’s mediums, trying to contact her eldest son, who had been killed three years before on the Western Front.

Stephen’s father, Lord Glenconner, wearing an extravagant bow tie, sits secure in industrial fortunes gathered in the previous century, and in the privilege of his position. In 1914 it had been Glenconner to whom the Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey turned and said, ‘The lamps are going out all over Europe; we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.’ Next to Glenconner, in a picture hat and tea gown, is his wife Pamela, product of a more poetic breed, the Wyndhams; as a young woman she had known Wilde. David, Stephen’s brother, wears a dark suit, his raffish future as a playboy and nightclub owner presaged by his suede shoes.

But it is Stephen who draws the eye, for all that he too was only in his fourteenth year. It was impossible for any camera to take a casual picture of him. He predicts himself, demanding attention through his own discerning eyes. He stands under a palm tree in his white shirt and wide tie, his trousers cinched with the kind of snake-clasp belt I also wore as a boy. On the family’s tour of America he gave dancing demonstrations in hotel ballrooms and painted pictures in a Beardsley style; his mother believed her son was spiritualistically inspired by Blake. And from the beach he collected abalone shells, ‘the kind with bluegreen iridescence’. They would become an obsession for Stephen, as if their nacre held the sea just for him.

By his coming of age in 1927, a very different one from mine, Stephen had reached the peak of his perfection. That year he was photographed in his Silver Room in the family’s townhouse in Westminster, where a streetlight illuminated the foil-covered walls and ceiling within, and dull silver satin curtains fell like waterfalls. A polar bear skin was splayed across the floor, parrots perched in a silver cage, and alligators languished in a glass tank. This icy reflecting chamber resembled an aquarium installed in a Georgian square. It was a reservoir of Stephen’s dreams. He might as well have kept a porpoise there too, fished from the frozen Thames.

Against a silver backdrop, the colour of water lit by an electric moon, Stephen posed for Cecil’s camera. Clad in a pinstripe suit, striped shirt and silk tie, he wore a shiny mackintosh, enhancing his mercurial sheen. It was the most outrageous act of cross-dressing.Stephen had assumed the conventional attire of a City gentleman. Never had pinstripes seemed so unconfining, no tie so decadently tied. Their ordinariness was stranger than his made-up face and halo of lightened hair. He was an alien in Mayfair, a star of his own making, posing for an album cover in a room as fabricated as Warhol’s Factory. In public he appeared in pageants as a pearl-clad Romeo or as Shelley, ‘gold-dusty with tumbling amidst the stars’. But in more intimate entertainments, Stephen and his friends were filmed all the while by a tall, dark young footman in spectacles, rehearsing scenes yet to come.

In retrospect 1927 seems a signal date, caught between what had happened and what was to happen, as if history could go either way. That same year Virginia Woolf created her Orlando, whose conflation of glamour and gender mirrored Stephen’s: ageless, aristocratic, fluid and vulnerable. The endless rooms of Orlando’s palace are awash with exquisite things from the past, ‘when the silver shone and lacquer glowed and wood kindled; when the carved chairs held their arms out and dolphins swam upon the walls with mermaids on their backs’; and to animate his domain, ‘he had imported wild fowl with gay plumage; and two Malay bears, the surliness of whose manners concealed, he was certain, trusty hearts’. (Vita was once given a Russian bear cub; it had to be put down.) One room is entirely silver, down to the counterpane, although Orlando considers this a little vulgar.

Nor was it by chance that in 1927 Rex Whistler portrayed Stephen as Prince Etienne in his Tate Gallery mural The Expedition in Pursuit of Rare Meats, ‘an Arcadian strip cartoon’, as his brother Laurence called it, with its anachronistic figures in eighteenth-century dress riding bicycles, their hair Eton-cropped. Stephen’s legend was being played out ahead of him. To further honour this dauphin’s adulthood, which would never really arrive, Stephen was sculpted by Jacob Epstein, who was not sure if he was a boy or a girl, but portrayed him half-naked, much as the starman had been photographed as a diamond dog. As Stephen watched himself taking shape in the artist’s hands, he declared, ‘this exquisite grey creature looking like a drugged, drowned Parsifal … when I am dead & forgotten its loveliness will live, gazing back into the past at me – where Ghost meets Ghost’.

Although they seemed not to have caught what Cocteau called ‘the illness of time’, all too soon the passionate bright young things burned themselves out. Stephen and his lover Siegfried Sassoon escaped to Sicily, a legendary island, where Stephen lay about in satin pyjamas while Siegfried, who had once fought the Germans in the mud of the Western Front, cleaned the shells they’d gathered from the beach. Stephen felt that they contained their love. But they became empty echoes when he had to send his lover away; Stephen could never bear too much reality. By 1935 he had retreated to his Wiltshire home, Wilsford Manor, where the river ran clear through his garden and the water meadows beyond. Restless, lovelorn, he wandered to Sussex, to visit Virginia Woolf at her riverside house and its flooded chalk valley. Woolf saw him often that summer and found his attentions amusing, although she looked upon him as a ‘fish in a tank’, so Stephen Spender told me.

What did she see in Stephen? Her letters and diaries of the time follow him and his like with a kind of amused disdain, filled with scenes of the half-life of high society and its shimmer. In one of her albums, along with all the photographs of her and Vita and their spaniels, and Lytton Strachey and Tom Eliot on English summer days, there is a caption in her hand – ‘Stephen Tennant’ – but like those nude photographs of her and Rupert Brooke, the picture is missing, edited out by history, and there is only a blank space where Stephen used to be.

Yet they were not so far apart, these two, attuned to their inner loneliness, fragile in the face of the modern age. Virginia was forced to stay in bed in order to control her mental illness; Stephen, having suffered from consumption as a young man, chose to stay there: for both, such instability seemed a reaction to the speed of the twentieth century. When she returned to Rodmell after lending her house to Stephen, Virginia wondered if she’d find the bathroom littered with his cosmetics; but he had moved down to the coast and the Bay Hotel, set on the cliffs at Seaford. He bought a new journal in the town, and on its cover painted a neo-romantic seascape overlooked by a classical bust and a sailor hailing from a placid quay.

The reality was somewhat different. Seaford was known for the huge waves that crashed over the sea wall in autumn and winter, smashing windows and damaging buildings. In the early hours of 17 September 1935 a terrific storm, the worst for many years, swept down the Channel. In the tempest, all fancies were forgotten. How could anyone sleep or even live through such a storm?

Stephen was woken by the sound of shattering glass. Rushing out to the landing, his plush monkey in his hand, he looked down on the moonlit scene as the sea lashed the shore. ‘I sat in the upper landing window – & watched vast ghosts form & dissolve on the esplanade – waves, giant waves.’ The winds, roaring at one hundred miles an hour from Folkestone to Plymouth, tore boats from their moorings even in protected Southampton Water, and claimed several lives. The next day Virginia drove down to Seaford to see the waves exploding over the lighthouse; she was prevented by the police from driving along the flooded road. Meanwhile, along the coast at Brighton, the doors of the Victorian aquarium – a subterranean chamber where porpoises, a beluga whale and two manatees were kept in the nineteenth century and where, in the nineteen-seventies, I would watch dolphins perform in a space resembling an underground car park – were burst open by tons of seawater and shingle driven in from the beach, flooding its interior six feet deep and all but allowing its inmates – among them a twenty-seven-foot-long stuffed basking shark – to return to their rightful homes.

Throughout the night Stephen’s ‘transparent dreams’ were assailed; the windows banged and the rain lashed the ground, and his calm was only restored in the morning, when the bright light of day brought a letter from Morgan Forster, who was coming on a visit. A week later, having moved inland to Forest Row to escape the raging sea, Stephen sent his Rolls-Royce to the station to meet his friend, who may or may not have been surprised to find bouquets of roses, gladioli and carnations arranged inside, with a pair of tropical butterflies perched quiveringly on the flowers, their frail beauty Stephen’s gesture to the aftermath of the storm.

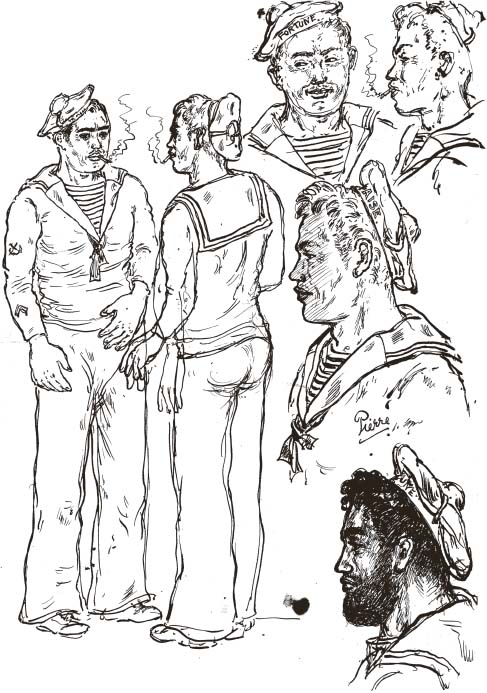

As an ‘aquaeous’ darkness fell outside the dining room, the two men talked late into the night. They spoke of Stephen’s evening with T.E. Lawrence in his hut-like cottage in Dorset; Morgan liked Stephen’s description of the hero of Arabia talking in ‘morse code’; the memory was more acute because Lawrence had since died after an accident on his motorbike. Morgan recounted his recent dinner with Noël Coward, whose equally staccato voice he imitated, and recalled a weekend in Amsterdam with Christopher Isherwood, Klaus Mann and Brian Howard. Then the two men fell to discussing Moby-Dick and the character of Queequeg, the tattooed savage, who fascinated them both. In an essay published in 1927, Forster had called Moby-Dick a ‘prophetic song’ beyond words, and saw Billy Budd as a ‘remote and unearthly episode’, its sadness indistinguishable from glory. For his part, Stephen’s love of Melville merged into the photographs of sailors he stuck in his journal and the fantastical Lascars of Marseilles he drew alongside them, characters from Jean Genet out of Jean Cocteau.

The convivial evening ended with Morgan playing the piano and reading aloud from his stories. But when he announced he had to go, Stephen incurred his displeasure by quoting Virginia, who had complained, ‘Morgan’s always in such a hurry to leave me.’ Stephen could not imagine why anyone would want to leave him.

On 20 November 1935, Stephen sailed from Southampton on the White Star liner Aquitania. He was bound for America, a journey Virginia had been able only to imagine. A century before, Robert Browning had written, ‘there is but one step to take from Southampton pier to New York quay, for travellers Westward’. The transition was seamless for Stephen, whose home travelled with him, carried into that great white vessel like the starman’s wardrobe.

He took: a new blue jumper with red zips by Schiaparelli, a powder-blue hussar uniform with silver braid and skin-tight breeches, and a sensible herringbone suit for the country (Rex Whistler told him it looked like the kind worn by men who said, ‘Well, I’m going to turn in’); a travelling library that ran from a biography of William Beckford to Sylvia of Hollywood’s beauty tips, No More Alibis; numerous cosmetics, perfumes and journals; and a little ‘Jane Austen’ cabinet containing his most precious shells. Stephen had only reluctantly turned down a suggestion by Peter Watson that he should take his new Rolls-Royce as well.

Six days later, after an unsteady voyage installed in a stateroom on A Deck – Rex was travelling on B Deck below – Stephen arrived in Manhattan and was swept from the honking, bustling streets into the solace of the St Regis Hotel. There he rang down from his nineteenth-floor, pistachio-green suite, where he was reading the New Yorker, to Rex on the fifth, to say that he was too tired to dine with Tallulah. He was saving his energy for Willa Cather.

Ever since he was a teenager, Stephen had been fascinated by Cather, whose novels evoked the sea of grass of Nebraska and the prairies where she had grown up as a tomboy, complete with a crewcut. Now she lived in New York, where she would walk barefoot in Central Park every day to reconnect herself to the land. After writing fan letters to Cather for nine years, Stephen was about to meet his heroine. She greeted him at the door of her Park Avenue apartment wearing a flamingo-pink satin tunic and black satin trousers – he couldn’t believe he was talking to the author of A Lost Lady and My Ántonia. Over tea, these two gender-challenging people – an English aristocrat and an American pioneer – discussed Cather’s favourite places in New England. And so, a few days later, Stephen left New York and Tallulah and Cole Porter and Elsa Maxwell behind and journeyed north to Massachusetts where he settled for the winter, like a migratory bird.

He checked into Mount Pleasant House, a shining, snowbound hotel in Jefferson, its verandah overlooking the same mountains that the Fruitlanders saw from their utopia. And there, in the New England countryside where the Apostles of the Newness had wandered penniless in chintz smocks, Stephen, an itinerant soul insulated by his own sense of beauty and letters of credit from London, watched as the snow fell in ‘great white goosefeathers’, their drifts casting ‘the longest sapphire shadows’.

In his solitude he’d take the bus into the nearby town of Worcester, passing wooden houses which looked rather temporary, as if they were made of matchsticks, the rocking chairs on their porches put away for the winter. The countryside rolled past the bus window, its low pines and sandy grass all dusty with frost and snow. One evening Stephen walked to the Jefferson village post office as the sun was setting. ‘The snow was an oblique toneless white, the sky startling in its clarity … shaded like some tropical bird, soft saffron yellow – deepening to flamingo pink & then to violet … the cold seemed to hold & embalm the moment.’ Stephen had only stepped into the shop – to buy more amethyst-coloured vases – when the sky had turned ‘gentian blue, the stars in freezing splintering splendour – the snow a dim miraculous glimmer on the ground’. He felt blessed by the place, free in this New England.

On Christmas Eve, Stephen left Jefferson for Jaffrey, being driven thirty miles north – Pas plus vite, monsieur, nous ne sommes pas presses – into New Hampshire. The Shattuck Inn was still run by the same family, the Austermanns, whom Cather had known when she had begun her visits there twenty years before, writing her novels in a tent in a field before moving into the inn, and rooms which were reserved for her at the top of the building so she wouldn’t be disturbed by other guests walking overhead.

Like Thoreau, Stephen wrote in his journal because he was lonely. He liked the Indian names of the places around him – Pawtucket and Lackawanna – and relished the fact that he was only an hour from the house in which Emily Dickinson had spent most of her life as a recluse – ‘one hour from Paradise in any latitude’. All the while he received a stream of letters and telegrams from Cather, anxious that he should be enjoying the place she loved: ‘Please write to me when you can, everything you think about the country, and everything you do there will be of intense interest to me.’

The Austermanns were certainly solicitous of their titled guest. Their son George – ‘such a nice boy … I was reminded how well I like ordinary brown hair’ – would drive Stephen into town so he could shop for snappy American clothes and admire the Christmas lights, so much more gay and splendid than those in England. A handsome Norwegian ski instructor, John Knudson, took Stephen to a trail in the woods which he was working on. Stephen sat on a pile of logs listening to the chickadees as John chopped down saplings; he even cut down one young birch himself, ‘& only felt sorry 3 hours afterwards – we were so happy & busy’. John told Stephen about his brother in the Canadian Mounted Police, ‘& we discussed the joys of camp life’.

Stephen’s love of nature sat oddly with his life of artifice. He revelled in pigeons and chipmunks and mice – ‘when I want solace I think of the raccoons faces’. But like Thoreau he surveyed his utopia of one, created in his own image; there was no room for anyone else. And where Thoreau was deemed ugly and Stephen beautiful, and the former lived in a wooden hut and the latter in a stately manor, the two men’s spirits shared the same state of separation and ecstasy, standing apart from the world in order to better regard it. They even shared the same poetic disease, consumption. Perhaps they might have set up home together, these two, holed up in another hut in the woods, albeit one exquisitely decorated, probably in chintz. If Stephen could win round Willa Cather or Virginia Woolf, I daresay the philosopher would have soon been rapt by his tales of curious mice and the latest haute couture.

But that winter, New England outgrew its romantic appeal. Stephen was haunted by his broken relationship with Sassoon – and despite the comforts of Whipple’s Cosy Café, of trinkets and little vases bought in Jaffrey’s shops, of excursions to Boston in the snow, drinking sickly liqueurs in smart hotels – in spite of all of this, he fell ill, as much with nostalgia as anything else, and not even Cather could console him. ‘You have seen our winter at its most terrible,’ she wrote; ‘there has been nothing like it since 1917. But there’s a kind of glory about blizzards, don’t you think? not when you are ill though, poor boy.’

Extreme weather seemed to follow him that year. Where he had been disturbed by the storm at Seaford and its rising waves, Stephen now felt oppressed by the snow that came dun-coloured with sand from the west, besmirching its beauty. His mood lowered as the season dragged on, and the glamour was replaced by a greater grimness. The gay nineteen-twenties in which Stephen had shone like a shooting star had been replaced by a different, darker, more punitive decade.

‘Europe continues to grind its teeth,’ he wrote on 11 March 1936. ‘Hitler has re-armed the Rhine, France is hysterical with fear – rushing guns & planes to the area. Flaudin demands that German troops be ousted. Eden wishes to consider Hitler’s peace pact suggestions … Nazi troops by radio-wireless photos entering Cologne – while girls cheer & pile flowers on to them. Outside my window – old dirty snow slips with a soft rushing sound off the roof – mild rain – wet air blows in.’ Stephen’s response to European politics was to order perfumes from Paris via Boston – Caron’s Fleurs de Rocaille, Millot’s Crêpe de Chine (which Siegfried had once given him in the Pavillon Henri IV, St Germain), Guerlain’s Shalimar and Liu, Chanel’s No. 5, and Gabilla’s La Violette – an exotic, narcotic library whose old-world scents might, by their civilised fragrance, exorcise the evil stench.

But these evocative distillations – many of them containing ambergris, the essence of the ocean derived from deep-diving whales once hunted from New England’s whaling ports – failed to achieve their magic. Here, on 14 March 1936, Stephen’s journal ends abruptly with a pencilled note, in what I thought was a literary quotation – ‘thinking of the wonder & exstasy of being alive – I feel that although I am often unhappy & disappointed – it is never life’s fault – always my own …’ – yet which, when entered into a search engine, comes up with references to clinical depression.

Twelve years later, after the world had been overturned by war, Stephen was taken to a clinic outside London and electric currents were passed through his brain. The rubber contacts were placed on his golden hair, as they would be clamped onto Sylvia Plath’s blonde head, the Bakelite switch was turned on, and Stephen’s body shook with convulsions. The machine sought to shock him out of a melancholia that a later tenant on the Wilsford estate, Vidia Naipaul, would diagnose in his reclusive landlord as accidia or ‘monk’s torpor’. It left Stephen bereft and abandoned.

The violence – external and internal – had even threatened his home. During the war Wilsford had been requisitioned as a military hospital; the nurses complained that wounded soldiers should not be expected to use lavatories which had been painted gold. For his part, Stephen’s greater contribution to the conflict had been to climb one of the Wiltshire downs and lay a bouquet of flowers at its summit. He was right, of course: chalk turf and rising larks were more sacred than any cenotaph. But Stephen closed his eyes to death, and when Virginia filled her pockets with stones and stepped into the river to drown herself, he could barely bring himself to register the loss.

He had spent most of the war in a suburban-looking nineteen-thirties flat in the centre of Bournemouth. From there he wandered the parks and chines whose pine-scented air was believed to aid the tubercular, as well as evoking his beloved Mediterranean. His fellow consumptives Robert Louis Stevenson and Aubrey Beardsley had come here for their health, although the resort failed to expel the infection from their lungs – Beardsley had haemorrhaged onto the clifftop path, leaving vivid crimson flowers in his wake. For Stephen, walking or bathing on the wartime strand was problematic: it was strung with barbed wire to keep out the expected invasion.

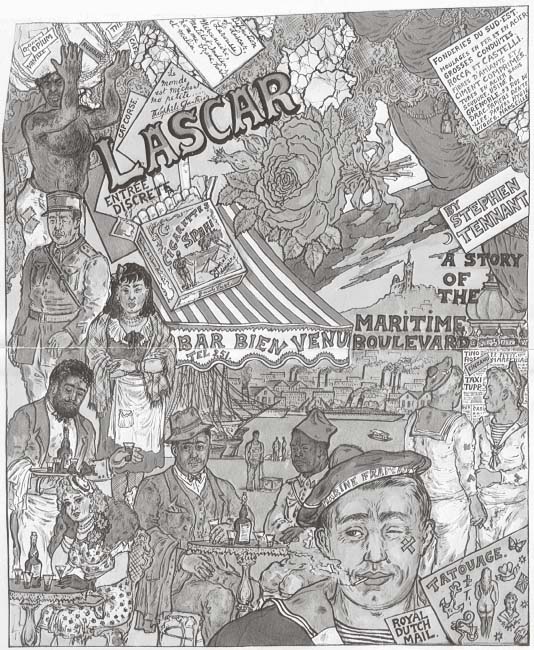

With the coming of a sort of peace, Stephen returned to Wilsford. As the trees grew taller around the silent manor, he retreated into past glories and future triumphs. He became obsessed with his would-be masterpiece, Lascar: A Story of the Maritime Boulevard, whose quayside tarts and muscled Lascars he drew over and over again in increasingly crowded images, as if they couldn’t be confined by the page: the women extravagantly costumed like operetta versions of themselves, the sailors’ bodies graphic with tattoos, while their faces all seemed to have the same features, the idealised matelot of his dreams. Spilling out into its margins, Stephen wrote endless notes to himself in ever-changing ink, cerise and turquoise and vermillion, along with poems about a boy with broken rose-red wings falling into a sea full of tears. He announced, in a self-published flyer printed in Portsmouth, that his book’s spiritual godparents were Joseph Conrad, Emily Brontë and Herman Melville, that it would bear ‘the sea’s illimitable detachment’ and ‘restlessness and mysterious moral strength’, and he had its cover published in Horizon.

But his work would never be imprisoned between hard covers. Like Orlando, who produces screeds of plays and poetry, there was a sense that it would be vulgar for Stephen’s work to appear in public: ‘to write, much more to publish, was, he knew, for a nobleman an inexpiable disgrace’. As the modern world encroached and he went nowhere, he entered an extended reverie of retrieval, travelling backwards into a vanished life preserved in his journals. ‘It was dawn – I was flying … I remember the seaplane as it rose above Southampton – slowly turning – and then going on straight – on & on into the first delicate radiance of early sunrise.’ In his mind’s eye he was still sailing down the same waterway in an ocean liner with a retinue that included his valet, his nanny and his plush monkey; or taking off from another airport: ‘The Prince of Wales is getting into his aeroplane which stands next to mine.’ He was lunching with Gertrude Stein in Paris, and taking tea with Willa in New York, or checking into Brown’s Hotel in London: ‘This morning when I ordered breakfast by telephone the waiter said, “Yes, Madame.”’

And just as he was forever rewriting Lascar in kaleidoscopic colours – merely starting back at the beginning once he had reached the end, so that the entire enterprise became one endless loop – his house was continually reset as a stage for his memories. Its many rooms, once so full of family and visitors, like Mrs Ramsay’s, were now filled with things rather than people. Straw hats from lost summers stayed on the newel posts of the stairs. Stephen replaced emptiness with dreams. His letters lay piled by his side, his jewellery and make-up and books and scarves gathered about him. The pale tide of a pure white carpet laid down when Wilsford had been a luxurious heaven in the nineteen-thirties, like some private film set, was now splattered with starbursts of carmine and ultramarine and emerald as Stephen dipped and discharged his pen, leaving shiny mineral-animal deposits like ground-up shells or crushed butterflies. Outside in his English garden, he ordered twenty-two tons of silver sand to be spread on the lush green riverbank, creating a simulacrum of a Côte d’Azur beach, complete with wheeling palm trees. Tropical birds and lizards escaped from their glass houses and into his illuminated manuscripts; in the winter they took refuge in the conservatory, where they kept Stephen company, listening to South Pacific on his Dansette over and over again.

Meanwhile the sea invaded his bathroom, its tub and basin filled with shells on which Stephen left the taps running, since, as we all know, they look better that way, the way they do in the water. Stephen himself had been left behind by the tide, like Orlando, who returns to her palace of three hundred and sixty-five rooms surrounded by lawns like a smooth green ocean, wandering into a bedroom that ‘shone like a shell that has lain at the bottom of the sea for centuries and has been crusted over and painted a million tints by the water; it was rose and yellow, green and sand-coloured. It was frail as a shell, as iridescent and as empty.’

It was now that Stephen’s obsession began to overwhelm him, in waves of memories merging into one so that it was difficult to know what was real and what was make-believe, whether he was in Wiltshire or Acapulco. His house became inundated as surely as Brighton Aquarium in the storm of 1935. Multicoloured fishing nets from San Francisco were draped over the banisters as if to catch passing fish; the shells in the bathroom spilled out onto the landing and down the stairs; and Lascar became an ever more elaborate reef of words and images, encrusted with salt and ink.

To Stephen, as to Virginia, the sea was a place in which to be subsumed. As young students at the Slade, he and Rex Whistler had united in their desire for a Kingdom by the Sea, an image from Edgar Allan Poe’s last, doomy poem, ‘Annabel Lee’, which they both loved: ‘I was a child and she was a child | In this Kingdom by the sea.’ At that peak of his youthful beauty, Stephen had posed for Cecil’s camera on the rocky shore of Cap Ferrat clad only in a fake leopardskin, and had sketched himself half-drowned in a pool, a Narcissus under a serious moon. Thirty years later, Beaton captured Stephen in a photograph in which, purposefully propped up on an ormolu table with its cover turned to the lens, was a copy of Rachel Carson’s The Edge of the Sea, a book devoted to ‘the place of our dim ancestral beginnings’.

Stephen was now a spectacle all of his own, washed up with his treasures on his bijoux-strewn divan. Beaton brought Isherwood and Capote and Hockney to listen to tales of dear Morgan and Virginia’s peculiarities; Kenneth Anger and Derek Jarman came to hear stories of Garbo and the Ballets Russes and planned to cast him in their films. Stephen’s life had become a movie clip endlessly rerun, ever more scratched and misted.

And there, one afternoon in the autumn of 1986, I was admitted to his darkened bedroom in that closed-up, sleeping house. He lay on an ice-blue satin bed in a room with the curtains drawn tight against the day, as if he might fade away in its light. One bar of an electric heater glowed in the corner; a bare bulb shone faintly from the ceiling. The wind shook the windows and rattled at the latches, stirring up the leaves outside and pushing them through a gap at the foot of the front door. The ancient wilderness was ready to take over, only biding its time. Out of the gloom, Stephen offered me his hand, weighed down with a scarab ring. I reached out with mine. In a fluting voice from another era, he asked, ‘Do people still think of me in London?’ As we shook hands I was conscious of what was passing between us: a secret world, and all the people I had never met.

Then I left him to his dreams and wandered alone around the great empty house, its every surface, from the stairs to the floor to the furniture, covered with books and paintings and letters. Downstairs, in a silver-curtained library, draped over a silver satin chair, was Stephen’s hussar’s coat, its epaulettes and braid spilling over the back of the seat; there were Venetian silver-gilt grotto chairs carved in the shapes of shells, and around the room ran a frieze of plaster scallops, encircling his kingdom beneath the sea. All the while, in the stillness, I could hear Stephen upstairs, laughing and talking to himself, as if the party were still going on and I was the last guest to arrive.

One year later, the Great Storm of 1987 swept up the Channel and into southern England; its hurricane-force winds felled fifteen million trees. At Wilsford, the palms swayed in the garden and as the storm rose to its height that night, one enormous branch smashed into the glass conservatory.

But none of this disturbed Stephen, since he had become ashes, and his earthly remains now lay in the churchyard next door, slowly sinking into the soft green turf.