The branch line to Portsmouth Harbour just stops. Its rails cut off, as if the train had carried on into the sea. The station hangs over the water, its platforms resting on a rusting pier. At the far end there’s a big old wooden clock which used to advise passengers of the time of the next ferry, but its hands have long since stalled.

Through the windows let into the side of the station you can look out, depending on the tide, to a seaweedy waste where mudlarks once wallowed for pennies thrown to them by onlookers; or to a swelling steely sea, buoying up the bulk of HMS Warrior – an ironclad, forty-gun Victorian deterrent so effective that it never saw action. Its long, low presence is now tethered impotently to the quay. Uniformed men patrol the historic dockyard beyond. This is still a working place, although its boathouses and roperies, semaphore towers and smithies, ship shops and basins long since ceased to be essential, outmoded by the ominous presence of modern warships, their sea-green superstructures surmounted by gun turrets and radar domes.

Encircled by a high wall, the dockyard is an insular citadel, with its own subsidiary isles. To the north, tucked into the harbour’s inner shore, is Whale Island. It lost its nominal shape in the eighteen-sixties when it was expanded with debris dredged by convicts. What exists now, joined to the mainland by a causeway, is a functional place, surrounded by silty mud still seeded with wartime bombs; a dead zone where ships go to die and where, on family visits to Portsmouth, I’d see stranded submarines like abandoned bathtime toys. I may have been conceived by the sunny seaside, but my mother, brought on a visit to a submarine when she was heavily pregnant, nearly gave birth to me here, underwater. It’s a wonder I wasn’t born with a caul.

In the late nineteenth century, Whale Island became home to a Sailors’ Zoo, stocked with animals that had been presented to ships’ captains as gifts for the royal family. Centuries ago such beasts might have ended up in the Tower of London as part of the monarch’s menagerie, but now their fate had fallen to men whose wandering had turned their hearts sentimental. According to a 1935 edition of The Times, the zoo ‘grew out of the sailor’s fondness for pets of all sorts, and the care he gives to their well-being’. Somewhat worryingly, it also overlooked the parade ground of the island’s gunnery school, as if its inmates might provide exotic target practice.

It was a reflection of the navy’s secret love of eccentricity, bred by its romance with the sea. ‘For lions and other animals there are spacious iron cages, much like those of the Zoological Gardens. The marsupials have large grass paddocks to roam in; for the aquatic birds there are big ponds, and there are large aviaries for birds of other species.’ It must have been odd for locals to hear the island’s strange noises from over the water, as if a little bit of Africa or the Arctic had been towed into the harbour. The collection was a growling, squawking index of colonialism, complete with a Shakespearean bear pit. ‘Among its first carnivora’, notes The Times, was a polar bear named Amelia, given by Inuit people to HMS Grafton in 1904. Her fellow inmates included one of Captain Scott’s sled dogs who had done brave duty in the Antarctic, and a parrot named Calliope Jack, the sole survivor of HMS Calliope after it sank in a Samoan storm. Jack was the zoo’s veteran: he lived for thirty-nine years on Whale Island, and died in 1919. Another resident, Tirpitz the pig, was rescued from a German warship off the Falklands in 1914. Kept onboard as food, he had been left below when Tirpitz was scuttled, and managed to make his way to the upper deck. He swam for an hour towards a British ship, one of whose officers nearly drowned trying to save the frightened animal. Tirpitz too spent the rest of his life on Whale Island, before performing his final service on a dinner table.

The island had become an animal League of Nations, a melancholy ark. In 1940, its last captives met an abrupt end: on 27 May, lionesses Lorna and Topsy, polar bears Nicholas and Barbara, and sun bears Henry and Alice, were summarily shot. It was a logical move. Apart from fears that the animals might escape and terrorise the city, the country as a whole anticipated food shortages and air raids during which, civilians were informed, no pets would be allowed into the shelters, nor would they be included in rationing. Along with the non-human occupants of Whale Island, domestic animals became the first casualties of war. All around Britain, owners gave up their dogs and cats to be put down. In 1939 – within a week of the publication of an official government pamphlet advising ‘it really is kindest to have them destroyed’ and recommending the ‘“Cash” Captive Bolt Pistol’ as ‘the speediest, most efficient and reliable means’ of doing so – three-quarters of a million pets were shot or gassed, long before the first bombs fell.

There are no caged animals in Portsmouth Harbour now. Rather, centre stage in the port’s stalled drama stands the single most significant historical artefact in Britain: HMS Victory, which I boarded that morning, for the first time since I was a boy.

Victory still stands close to the sea, but unlike Warrior it lacks the reassurance of the waves lapping its hull; its magnificence is marooned in a dry dock. This morning part of its prow is rudely exposed, the bride stripped bare of layers of paint, subject to constant conservation work. The ship’s regal state is somewhat diminished by this care and attention, like a proud octogenarian forced into a nursing home; and by the fact that it has been upstaged by a third warship, one which didn’t manage to stay afloat at all: Henry VIII’s flagship, Mary Rose. After marinating in the Solent for four centuries, the wreck was hauled from the turbid water, and now lies under cover in climate-controlled gloom, its splintered timbers slowly being sucked dry of salt water as their expanded cells are pumped full of silicone. If this is surgery on a grand scale, then the low hum of machinery in the darkness lends the extended shed the air of a giant intensive-care unit.

Arrayed around her – I fall into the gendered terms, seduced by these ships, as much mothers as mistresses, and their crews as lost boys – are the objects the drowned crew left behind. They’re displayed in faintly-lit glass cases, like one long aquarium. I’m peering into the aftermath of disaster: from the surgeon’s velvet skullcap to personal sundials, Tudor wristwatches; from immaculately preserved longbows made from French yew to skeletons of the six-foot archers who used them, their overdeveloped right arms testament to their profession. Peter, my archaeologist friend, points out grooves where strong muscles were attached, and jaws where the bone grew over empty tooth sockets so smoothly that in some the entire lower mandible became one gummy structure.

These objects are dumb, but they speak of the last moments of five hundred men, their names lost to the sea. A hide jerkin which once spread over the substantial chest of its anonymous owner was impressed with his ribs as he came to rest in the mud, leaving his shape in leather. In a nearby case is another nameless skeleton: the ship’s dog. The label supposes it was kept to control the rats foraging on scraps dropped by sailors, but it is easy to imagine how it was loved, too, for its own sake.

Given the contemporary attention lavished on this Tudor wreck – the sort of ship that might have foundered off Prospero’s isle – her eighteenth-century counterpart seems vaguely forgotten, as if she’d been wheeled out of the ward and left to fend for herself. Dismasted and deprived of her figurehead, Victory is naked, exposed to tourists’ stares and all-seeing smartphones. And where Mary Rose is plumped up with silicone, Victory is continually rebuilt in her own image, much as we are always regenerating ourselves. Her wounds heal over; her ship’s knees are as scarred as my own.

As I climb the gangplank – a route once restricted to officers with gold braid around their sleeves – I feel underdressed in my shorts and sandals, expecting someone to bark at me, ordering me to adjust my attire.

Ducking under the doorway, I bend to enter the hallowed maw of what is as much sacred architecture as historic ship. This revered interior, a lowered cathedral, requires genuflection. The layered decks demand obeisance to their holy timbers; the headbutting beams force me to bow. Most historic sites forbid you to touch, but here you cannot help it. You are in constant contact with the structure with hands and head and feet, perpetually aware that you are being admitted to a shrine.

‘It’s two hundred and fifty years old,’ an American woman tells her young son as they ascend ahead of me. It’s not clear whether this is a remark or a reprimand.

Winding through the wooden aisles towards the stern, we’re drawn into a burst of light like a nave. In Nelson’s Great Cabin, a personable, eager young rating in white shirt and black slacks (a term for which such an item is made) stands at ease, legs apart, behind the admiral’s table – a position which, two centuries ago, he could have occupied only if he were waiting on his superiors or awaiting sentence. Today’s handsome sailor imparts his information on a rolling, need-to-know basis, repeated with renewed enthusiasm for every new arrival.

The details are anecdotal, engaging. He tells us all about the en suite facilities the admiral had at his disposal; how he preferred to sleep in a specially designed low leather chair because his constant struggle with seasickness made his swinging cot an uncomfortable resting place; and how the entire interior was transformed for battle, its panels and partitions folded away and cannon rolled in as it became a war room.

All this is delivered with cheery briskness. I feel I want to take a breath for our guide, but he clearly enjoys his performance; he is, after all, flanked by superior set-dressing. In one corner stands a tall vitrine, just shy of the height of our instructor. It holds a headless dummy draped in a replica of Nelson’s full-dress uniform: a blazing, glamorous get-up, from his cutaway coat and red silk sash to the diamond chelengk on his cocked hat, plucked by Selim III, Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, from his own royal turban and awarded to the admiral for having won the Battle of the Nile. Stuck in his bicorne like a comet caught in its felted brim, its fêted recipient was the only infidel on whom this starry decoration had been bestowed. The outrageous assembly of eighteen diamonds – then valued at eighteen thousand pounds – was animated by a clockwork mechanism which slowly revolved its centrepiece, all the better to catch the light, while its thirteen wired rays – each representing an enemy ship defeated in the battle – trembled like studded feathers. Nelson loved to wear this ‘plume of triumph’, at a time when it was not usual for an officer to bedeck himself so. Sir John Moore, the British general, met Nelson in Naples shortly after the battle and gruffly described him as ‘covered with stars, medals and ribbons, more like a Prince of Opera than the Conqueror of the Nile’.

The glittering commander-in-absence illuminates the space, casting glorious rays on the proceedings. Far from the gloom of the rest of the ship, his day cabin is flooded with light: the stern is one long wall of glass, a giant Georgian bow window. The walls are delicate duck-egg blue; the floor canvas, painted to resemble the black-and-white tiles of an elegant interior. It might as well be a Regency drawing room as a working war office; a suitable setting for a Prince of Opera covered with stars.

But out of its princely glow, the mazy darkness returns, brown and murky. I climb on through the ship, feeling my way along the decks, as disorientated as if I were lost in a multi-storey car park; only here the floors are laden with three-ton guns rather than Fords or Audis. Victory’s sides are spiky with cannon which once disgorged a dragon’s breath, each discharging a pulverising death. The entire ship is an organic war machine, almost animal itself, looped and bound with hemp and canvas and wood and iron, soaked to the skin with tar and blood and sweat and piss. If a whale ship was slick with spermaceti oil, then this vessel, this container, was lubricated with the oil of humans.

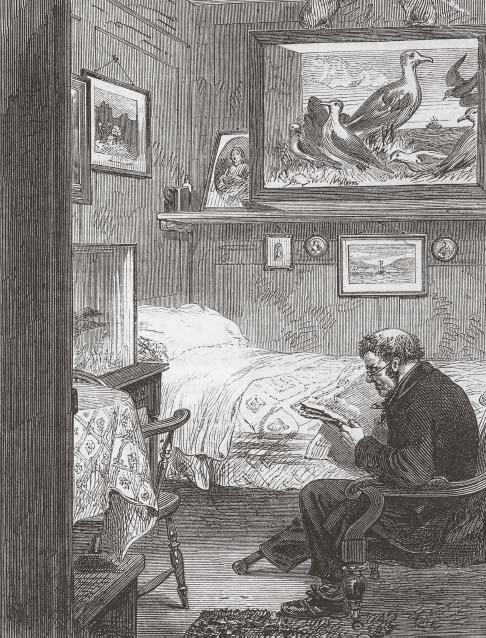

I’m funnelled through midshipmen’s cabins with their neat cupboards and plank bunks, past the galley – the only place on the ship where fire was allowed, in an oven the size of a carriage – down to the whale-belly bilges laden with pig iron and what looks like railway ballast, laid to steady this lurching leviathan. I’m led by an invisible, smelly sailor, head and body bent, along gangways and alleys and into dead ends where all manner of misdemeanours and conspiracies might have taken place while the officers were busy in their drawing room above, planning their next engagements over a glass of port. Finally, bending ever lower, I reach the place where he lay. It is marked by a gilt-framed copy of Arthur William Devis’s painting on an easel, displaying, a still from a Regency movie, a re-enactment of the admiral’s death.

Devis, an enormously successful but reckless artist who was let out of debtors’ prison to create his canvas, was allowed to board Victory on her return from Trafalgar so that he could sketch the principal players, both living and dead. Like Trelawny, he’d had his fair share of drama. He had served on an East India ship and survived an attack by New Guinea islanders during which he was wounded in the face, leaving him with a locked jaw. During his career he had reached great heights – he was paid an astonishing £2,530 for his portrait of the governor-general of India, General Charles Cornwallis – and great depths, having been imprisoned as a bankrupt. Now came Devis’s last chance to make a mark on posterity – and pay off his debts. His commission was the most prized in England. He would have to do it justice.

The artist stayed on the ship for a week, sketching every aspect of the scene with forensic detail, and when Victory sailed to Chatham for repairs to its own battered carcase, Devis accompanied it. He assisted William Beatty – the ship’s surgeon who had attended the dying Nelson – as they decanted the admiral from the alcohol-filled cask in which he had been pickled. Manhandling him like a giant fish, the two men dressed the hero in his uniform, preparing him for his final performance.

The means of preservation had left Nelson’s features distorted and discoloured, and despite Beatty’s attempts to restore them by rubbing, it was decided that Nelson looked too unlike Nelson, and unfit for public display at his forthcoming lying in state. Yet for Devis, it was an extraordinary opportunity. He could do what a doctor could not, restoring the dead with a gaudy slap of paint.

The finished canvas was, as Sir John Moore might agree, a suitably operatic scene. Nelson has been felled from above, and lies ashen and limp, his life ebbing away. His accoutrements and awards are discarded uselessly beside his body, which even now looks greenish, as if already steeped in fine brandy and sweet wine; his clothes lie at his feet, the surgeon having cut away his breeches to allow access to his wounds. Nelson was perfectly aware of the significance of his death – from the handkerchief placed over his face and medals as he fell so that his men should not recognise him, to his comment to Hardy, ‘They have done for me at last. My backbone is shot through’ – to his urgent request that his body should not be thrown overboard, as other bodies were being tossed into the Atlantic all around him.

Around his pale glowing flesh – ‘a dismal light about it, like a bad lobster in a dark cellar’ – gather mechanical figures. Like Rembrandt’s depiction of a dissection or a resurrection by Titian, Devis’s painting plays tricks with dark and light; it manages to be both overlit and obscure at the same time.

His rival, Benjamin West – a Pennsylvanian Quaker, now president of the Royal Academy, and celebrated for his spectacular Death of Wolfe – complained that Devis’s work was not an ‘Epic representation’, and that Nelson looked ‘like a sick man in a Prison Hole’. (Devis might have countered that at least he knew what such a hole looked like.) Given that West had painted his own version of the most famous event in British history, the contrast between the competing works – these aesthetic autopsies, both fighting for historical supremacy – is a wonder to behold.

West presents an action-movie version of Nelson’s demise, all red-coated marines and a pair of bare-chested sailors who wouldn’t look out of place fighting in a dance hall in Pompey tonight. Hats are raised, heroic stances struck. Every earnest, seaworthy face is turned towards the stricken admiral, who sinks gracefully like a stove schooner in his officers’ collective embrace. Meanwhile the battle rages behind, triumphantly won even in its victor’s fading light. To the boy in me, such scenes were thrilling. In my early teens I was obsessed with the Napoleonic Wars; I spent hours painting tiny metal soldiers with the peacock colours of hussars, chasseurs, dragoons, grenadiers, cuirassiers, lancers and mamelouks, their frogging, plumes, epaulettes, dolmans, pelisses, shakos and leopardskins the epitome of the exotic military dandy.

How much darker is Devis’s vision! Where there’s scarlet and gold in West’s painting, there’s murk and gloom in Devis’s. His is the mumblecore version of Nelson’s death, all whispers and shadows, imbued with mortality rather than pomp. One is a celebration, the other a Christian parable, a rousing crescendo or a plangent aria: both issue from a theatre of war which neither artist witnessed, staged on an immortal ship with its sails as backcloths, its crew as the angelic chorus, and its rigging as the stairway to heaven.

It’s all getting a bit fetid down there, fuggy with all this smoke and blood and guts, and I’m relieved to return to open air, ascending to the most sacred spot of all, the ground zero of British history. Screwed into the top deck is the plaque marking the place where the sniper’s musketball did its job, entering Nelson’s left shoulder to lodge between the sixth and seventh vertebrae, carrying golden threads from his epaulette as it travelled on its fatal trajectory, and skewering the heroic corpus in an Olympian apotheosis, forever falling back, over and over again.

HERE NELSON FELL

21st Oct 1805

Except that this is not where he fell, nor is this the ‘original’ plaque which once marked the spot. Like much of the ship, the quarterdeck has been replaced even since I last stood here. And this morning the timbers are being laid again.

‘What are they made of?’ my companion – who happens to be named Horatio – enquires of one of the workers, who is busy kicking a black bin bag full of rubbish over the place where he lay.

‘Wood?’ the man replies, pleased with his own sarcasm.

Not even hearts of oak; as Horatio points out, the new decking is comprised of tropical hardwood.

Suddenly, I feel fooled. Is any of this real? The cannon ranged along the lower decks have long since been replaced by fibreglass replicas, for reasons of weight and wear, we’re told; although the cannonballs are made of concrete rather than iron. The entirety of this ‘Victory’ might as well be a set for a seventies television production, with a different crew: a director in thick-rimmed spectacles and sideboards, lumbering cameras on wheels wielded by men in huge headphones, and a smart young continuity woman, clipboard at the ready. Someone plays some stirring music.

When the Athenians honoured Theseus’ ship by replacing its rotting planks, their philosophers agonised as to whether it was Theseus’ ship any longer, any more than a river is the same river as its waters constantly flow out to sea, or than you are the same you since your body has rebuilt itself many times since you came into being. We are memory, not history. At what point, in the transmigration of maritime souls, did Victory stop being Victory, if it ever did? For the long nineteenth century the Regency relic lay along the quayside, accessed by Victorian visitors by boat and ladder, reincarnated in the Victorian image like an over-restored country church; a Victorian version of what it should look like, rather than the Georgian ship Nelson had known. In 1922 it was brought into dry dock as a pageant, a nineteen-twenties edition of itself. In the Second World War it was a symbol of resistance while the dockyard buildings burned around it in the Blitz. Then it became a life-size Airfix kit for boys like me.

Now, in the twenty-first century, it is no more or less Victory than a forest is the sum of its replanted parts. In a Hampshire nature reserve, another plaque tells me that the oaks from which Victory was made took three hundred years to grow, three hundred to flourish, and three hundred to die. Perhaps the ship should be allowed the same dignity. In the interests of historical accuracy she ought to be left to rot there in the dockyard as a memorial to all that she meant, and now does not mean.

On Christmas Eve 1849, wearing his new green box coat, of which he was inordinately proud, Herman Melville took a cab from his lodgings in Craven Street, which lay just off Trafalgar Square and its lofty statue of Britain’s naval hero. The narrow road ran down from The Strand towards the unembanked shore, where the Thames flowed wide and filthy, ‘the inscrutable riverward street packed to blackness’, as Henry James would see it. After three months away from home, Melville was leaving London.

After a five-hour journey from Waterloo station, he arrived at Portsmouth, where he spent the night at the Quebec Hotel on the Point, a spit of land jutting out into the harbour. Nicknamed Spice Island, it had long been a lawless place, a huddle of taverns, warehouses and whorehouses. The hotel still stands, a genteel Georgian building, and its address – Bath Square, at the end of Bathing Lane – advertises its original function: as a bath house fed with salt water, the waves almost running into its dining room and up to its guests’ tables. Predating Torquay’s medical baths by half a century, the Quebec was a testament to a serious pleasure: that of entering the sea for its own sake.

The building is dwarfed on either side by stone ramparts. At their feet runs a slender beach where, in summer, old men with blurred tattoos turn the colour of coffee, and where local lads throw themselves off walls made to repel invaders, their pale bodies arcing into the water like seals. I swim there too, in the narrow channel dredged deep enough to accommodate aircraft carriers. I imagine Herman watching me from his room, before taking to the streets.

It was late December, and a cold wind blew up the Solent. That coat came into its own. This was the sort of place to which Herman was always drawn, like the Battery in Manhattan, where he was born; places where the streets stopped and the sea took over. On his early-Christmas-morning stroll, he ‘passed the famous “North Corner”’, as his journal records. ‘Saw the “Victory”, Nelson’s ship at anchor.’ Then he returned for breakfast, only to be rudely interrupted by news that the ship which was to take him home had appeared in the harbour. In a flurry of capsized coffee cups, he dashed to grab his bag, and set off on his voyage back to New York.

There is no hint, in his scant account, of Melville having actually boarded Victory; it was then a receiving and training station, not officially open to visitors, although ‘this would not prevent an enterprising sailor extending an informal invitation to come aboard for a few shillings’. But he certainly boarded it in his imagination: when Father Mapple delivers his sermon on Jonah from a pulpit-prow in Moby-Dick, ‘impregnable in his little Quebec’, a ray of light, shed from a window with an angel’s face in it, illuminates a spot on the chapel floor, ‘like that silver plate now inserted into Victory’s plank where Nelson fell’. Nor is it any wonder that this story so affected the young American on his visit to Portsmouth, since the shore from which he left England was the same from which Nelson embarked for his fated appointment.

On that last day on land, the vice admiral had tried to ‘elude the populace by taking a byeway to the beach’, only for a crowd to gather at Southsea, ‘pressing forward to obtain a sight of his face; many were in tears, and many knelt down before him, and blessed him as they passed’. It was as if he were already a saint.

The numbers swelled as they reached the sea wall, pushing towards the parapet, ‘for the people could not be debarred from gazing till the last moment upon the hero – the darling hero – of England’. At two o’clock in the afternoon, Nelson embarked from the bathing machines, and was rowed to Victory past the wheeled huts lined up on the shore.

A month later, on 21 October 1805, he strode on deck to face the enemy. In the literary accounts that match Devis and West’s paintings with their florid words, he was a standing target. According to the poet Robert Southey – on whose biography of the hero Melville drew – Nelson ‘wore that day, as usual, his admiral’s frock-coat, bearing on the left breast four stars of the different orders with which he was invested. Ornaments which rendered him so conspicuous a mark for the enemy were beheld with ominous apprehension by his officers.’ For his part, Melville saw ‘a sort of priestly motive’ which led Nelson to ‘dress his person in the jewelled vouchers of his own shining deeds; if thus to have adorned himself for the altar and the sacrifice’. In fact, that day Nelson wore his undress coat with sequin replicas of his awards sewn over his heart. Yet those paillettes and silver-gilt thread did indeed turn his coat into a conspicuous costume, ‘an ornate publication of his person’.

These stories preoccupied Melville, who was busy creating his own myths. In London, he had made a pilgrimage to Greenwich, taking the steamer from the Adelphi down the Thames; he was already familiar with the river, having crossed from Wapping by the new tunnel to Rotherhithe, ‘flinging a fourpenny piece to “Poor Jack” in the mud’. He even claimed to have seen a beggar on Tower Hill with a board hanging around his neck like an albatross – only it was painted with the whale that had bitten off his leg.

Greenwich’s naval hospital was well known for its veterans, identified by their own wooden stumps and archaic blue frockcoats and cocked hats which earned them their nickname, Greenwich geese. The building itself was a great ship beached on the riverbank, with figureheads on its walls and peg-legged sailors accommodated in ‘cabins’ along with their mementoes, from maritime paintings to stuffed seabirds.

Wandering along the terrace, Melville met a fellow American, ‘an old pensioner in a cocked hat with whom I had a most interesting talk … a Baltimore Negro, a Trafalgar man’. This chance encounter would assume a certain importance for the writer. During the Napoleonic Wars, many Americans were press-ganged into the British navy, ‘all kinds of tradesmen and Negroes’ – twenty-two on Victory alone. The Baltimorean told Melville that even the gaols were raided for crews.

In a photograph taken in 1854, five years after Melville’s visit, a group of Greenwich veterans sit on a bench. Among them is an elderly black man. Records indicate that one Richard Baker, born in Baltimore, served at Trafalgar on HMS Leviathan and later joined the pensioners; his ship was retired to Portsmouth Harbour as a prison hulk, holding convicts bound for Van Diemen’s Land. Was this Melville’s countryman? He sits in antediluvian company, an exotic figure clutching a cane, a medal on his waistcoat, his hair turned entirely white.

To Melville, this sailor, an alien like himself, was a living memory of a legendary past, in a place where time and space began and ended: embedded in the hill behind was a brass line over which one could step from one hemisphere to another. When he walked into the Painted Hall, Melville found fifteen hundred veterans at dinner; the contrast between the rough mariners in their frockcoats and the baroque interior was remarkable: ‘Pensioners in palaces!’ And in an anteroom he came into the presence of the hero himself: a row of glass cases filled with Nelsoniana.

Six years later, in 1856, Melville’s friend Nathaniel Hawthorne would also visit Greenwich. He’d just arrived in London from Southampton, where he’d seen Netley Abbey and was fascinated by the gypsy woman who’d lived in the ruins for thirty years. Ever attuned to the gothic, Hawthorne was struck by the Painted Hall and its sanctuary, ‘completely and exclusively adorned with pictures of the great Admiral’s exploits. We see the frail, ardent man in all the most noted events of his career, from his encounter with a Polar bear to his death at Trafalgar, quivering here and there about the room like a blue, lambent flame.’ For Hawthorne, as for Melville, Nelson was a legend. ‘But the most sacred objects of all are two of Nelson’s coats, under separate glass cases.’

One is that which he wore at the Battle of the Nile, and is now sadly injured by moths, which will quite destroy it in a few years, unless its guardians preserve it as we do Washington’s suit, by occasionally baking it in an oven. The other is the coat in which he received his death wound at Trafalgar. On its breast are sewed three or four stars and orders of knighthood, now much dimmed by time and damp, but which glittered brightly enough on the battle-day to draw the fatal aim of a French marksman. The bullet-hole is visible on the shoulder, as well as part of the golden tassels of an epaulet, the rest of which was shot away. Over the coat is laid a white waistcoat with a great bloodstain on it, out of which all the redness has utterly faded, leaving out of it a dingy yellow hue, in the threescore years since that blood gushed out. Yet it was once the reddest blood in England, – Nelson’s blood!

Seventy years and many wars later, these relics retained their power. In 1926, when writing To the Lighthouse, Virginia Woolf visited that Greenwich chamber and found it heady with emotion. The sight of the coat whose decorations Nelson had hidden with his hand as he was carried down, ‘lest the sailors might see it was him’; his ‘little fuzzy pigtail’ tied in black; and his long white stockings – ‘one much stained’; all these prompted her almost to burst into tears, ‘& could swear I was there on the Victory’.

In the Ordnance Survey of Great Britain, the Thames shore is accounted part of the country’s coast, the sea inside the city turned inside-out. Up until the nineteen-thirties the riverbank at Greenwich was used as a beach from which Londoners swam, as if it were a resort. Walking there a few years after Woolf’s visit, Denton Welch passed the desultory strand where the low tide still reveals blackened bones, empty oyster shells and the soft stems of clay pipes like the debris of some long-forgotten feast. On the shore he saw a pair of children playing ‘some spiritualistic ghost game … close to the horrible black water’. The young artist felt overwhelmed by the insistent sights and sounds of the river, ‘their never-ending story of time passing, longing, death’. Later, riding over the Thames on a bus at night, he looked down from the bridge into the swirling darkness and imagined how awful it would be to swim around its stone piers. He wondered if they had barnacles on them, and thought of the black mud at their edges, so deep that he might sink up to his neck in it. What if he were to see someone jump from the parapet? Would he dive in too, only for the suicide to clutch at him frantically, drowning him as well?

I realise, as I walk along the river, that my pockets are so full of stones I’ve collected from other beaches that if I fell in I’d probably sink as quickly as Virginia sank into the Ouse. One step over the embankment and there’d be nothing the modern world could do to save me; I would enter another world. The solidness of the stone edge only intensifies the intimation of mortality: when it replaced the beaches of the city, the embankment made the Thames flow more dangerously, ‘running away with suicides and accidentally drowned bodies faster than a midnight funeral’, as Dickens wrote. Its blocks still stand as gravestones for the lost, the two dozen or more souls who throw themselves into the river each year as it courses through the capital.

Behind me rise Wren’s colonnades and cupolas – ‘among the most splendid things of their kind in Europe’ – measuring out the imperial reach. This is London’s water palace, built to service its maritime empire. And at the heart of the baroque complex, so little changed that it is often used in films as a stand-in for the eighteenth-century city – is its chapel, its domed entrance draped with semi-naked female figures and captioned with Biblical exhortations for those who would take to the sea.

WHICH HOPE WE HAVE AS

AN ANCHOR OF THE SOUL

BOTH SURE AND STEADFAST

FAITH IS THE SUBSTANCE

OF THINGS HOPED FOR

THE EVIDENCE OF THINGS NOT SEEN

To one side stands a memorial dedicated to Sir John Franklin and his expedition, listing the crew lost on his ships Terror and Erebus. Overlooked by shards of marble ice – from which, as Woolf imagined, the explorers looked out ‘to see the waste of the years and the perishing of the stars’ – a disconsolate figure in mittens and boots mourns one of the lost, found by an American expedition in 1869 and whose anonymous remains are interred below, an unknown warrior of the Arctic.

Leaving this sombre interior, I cross to the Painted Hall and walk into a bursting polychromatic lightbox. Floodlit by huge windows, its vast murals are as vivid as a colonoscopy. This echoing space, where Melville watched the inmates dine, was a truly extravagant interior for such an ordinary purpose, created by the architects Wren and Hawksmoor and the artist James Thornhill. Its opulent canopy, a Technicolor trick of the eye, is animated with classical gods, monarchs and emblems of the four known continents – Australia was yet to be discovered – with New England represented by a Native American in a war bonnet; soaring across the walls are cosmological symbols of the seasons and stars. Washed by grey London light, the effect of this panoply is overpowering, sending the visitor below scurrying across the black and white tiles like a beetle.

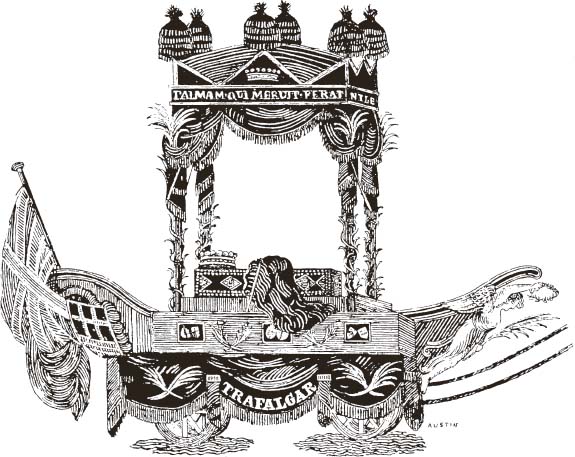

And at the point at which any sacred place would be dedicated to a saint there are two brass plaques let into the floor. One commemorates Vice-Admiral Collingwood; the other, his fellow commander. For three days in January 1806, thirty thousand souls trooped into this chamber, its windows boarded up and its murals deadened with black crêpe, lit by hundreds of candles. It was a sepulchral stage set, directing all eyes to the hero whose disembowelled corpse lay in a black-velvet-covered coffin studded with bronze symbols of a sphinx, a crocodile and a dolphin; heraldic familiars from his victories to accompany him into the afterlife.

The sheer press of people threatened to throw the arrangements into disarray; the authorities feared a riot. On 8 January Nelson’s coffin was placed on a barge and rowed up the Thames to the Admiralty, accompanied by so many vessels that one could have stepped across them from one bank to the other, and passed under bridges so crowded that bystanders fell off and drowned as a result of their eagerness to see the last of their saviour.

Brought to shore at the Whitehall Stairs, the bier was carried on a funerary car shaped to resemble Victory, complete with glazed stern and a figurehead bearing a victorious wreath. The procession was so long that its end hadn’t left Whitehall by the time its beginning reached St Paul’s; all the while, it was watched by murmuring crowds. Inside the cathedral, another Wren interior, a huge tiered wooden arena had been built to accommodate the congregation. The sound of military bands playing a tune to Psalm 104 – ‘Yonder is the sea, great and wide | which teems with things innumerable, | living things both small and great. | There go the ships, and Leviathan which thou didst form to sport on it’ – swirled around the Whispering Gallery, which was lit by one hundred and sixty Argand lamps burning whale oil.

Then, in a final piece of theatre which to one newspaper smacked of a ‘stage trick’, the coffin was lowered directly through the floor of the nave to the crypt below. Sir John Moore would have harrumphed. At that point, the sailors of Victory came forward. They were supposed to fold the colours and lay them on their commander’s coffin, yet such was their fervour that they tore the flag into pieces, the scraps of red, white and blue becoming relics of a man who had been translated into a myth.

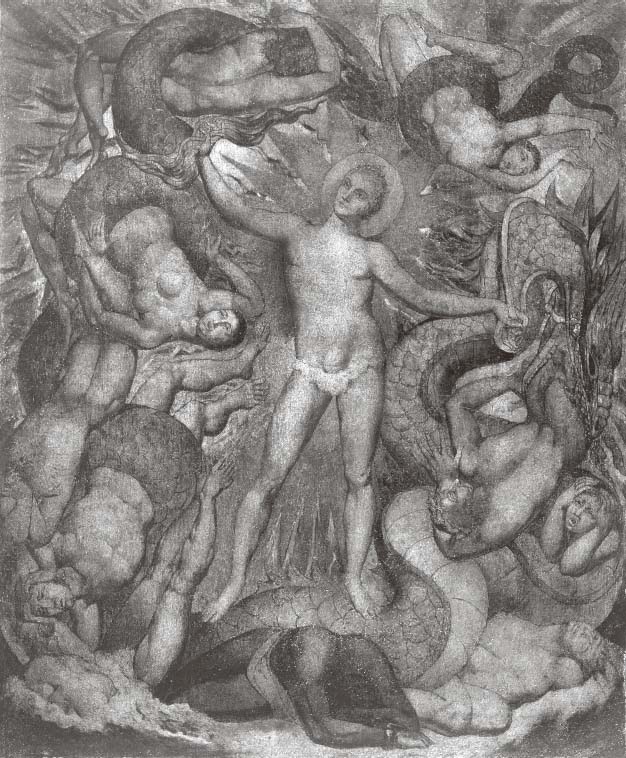

Meanwhile, a few miles away, William Blake was at work on his own mystical tribute – The spiritual form of Nelson guiding Leviathan, in whose wreathings are infolded the Nations of the Earth – in which the admiral rises naked and transcendent from the dead, an Apollo arrayed on the coils of a sea monster.

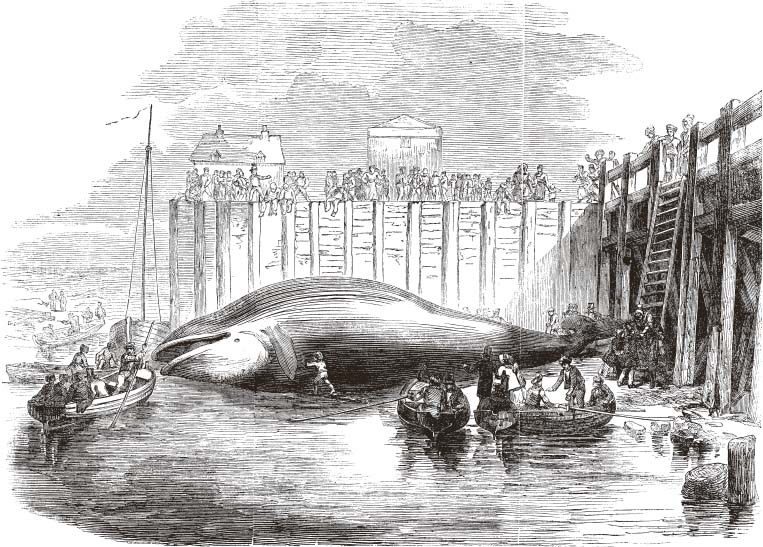

Three years later, as Blake displayed his finished picture in his brother’s Soho shop, the river received another body. In 1809 a ‘wonderful large fish’ was seen south of Greenwich at Sea Reach.

This leviathan – a seventy-six-foot-long fin whale – was shot, taking four hours to die, before being displayed at Gravesend: a suitably-named site, where the grey mud is the colour of a Weimaraner, where Pocahontas died of disease before she could return to Virginia, where Mayflower dropped down with the tide on her way to Southampton, and where Franklin’s Arctic explorers would attend their last service at a waterside chapel. Thousands viewed its carcase.

It seemed each generation summoned its own sacrificial beast up the river. In October 1849, Melville’s arrival in London was preceded by another whale, laid out on the front page of the Illustrated London News below a report on the Irish famine, as if he had imagined it out of his future story. Labourers had seen something dark floating on the water, ‘when suddenly the violent plunging and dashing of one end of it intimated to the men that it was some living monster of the deep’. The fifty-eight-foot fin whale ‘made desperate efforts to obtain its freedom’, but was duly lashed with ropes and dragged onto the beach where, ‘by the aid of a sword its life was dispatched, and the men then set about inclosing it for exhibition’.

The rain is pouring down at the end of an Indian summer as I cycle into the car park off Trafalgar Road, Greenwich. An anonymous warehouse stands before me; it might contain frozen foods or car parts. I sign in, deposit my soaking rucksack, and am conducted by Amy and Louise into a cavernous, climate-controlled space. Amy, who is from Pennsylvania, is lamenting London’s lack of an autumn. She strides to one of the giant racks and pulls out a wire grid on wheels. Hanging from it rather haphazardly, as if it had just been found in a skip, is a large gilt frame; and within the frame, a full-length portrait of Nelson painted by Leonardo Guzzardi to commemorate the Battle of the Nile in 1798. It was this victory which earned Nelson his chelengk – along with enough booty to please any pirate, including another diamond-set tribute from the Russian czar, a sable pelisse from the grateful monarch of Sardinia, and the dukedom of Bronté from the King of Naples.

In Guzzardi’s painting, commissioned for the sultan in return for his gift, Nelson stands resplendent in dress coat and white breeches, as bedecked as a Christmas tree. One arm points out of the frame to the enemy fleet he has destroyed. The other, of course, is lacking; his empty sleeve lies across his breast, both useless and potent. His stance is balanced; as the two curators note, it is that of a dancer rather than a fighter. ‘Everything in the eighteenth century was about the legs,’ Amy tells me. To modern eyes, the hero’s shoulders slope inordinately; all attention is focused downwards, in an unmistakeably sensual manner.

I see an entire era anew. It’s like being given access to a secret code, only to realise how obvious it was all along.

Nelson slips one slender leg in front of the other. His pose reminds me of Mr Turveydrop, the dancing master in Bleak House, a pomaded relic of the Regency, usually to be found ‘in a state of deportment not to be expressed’. The classical ideal, says Amy, was to look like a marble statue.

But all this civilian distinction, more suited to a ball than a battle, is dispelled by Nelson’s face. Only in this portrait are his wounds so visible; it is more pathology than painting, like a medical illustration from the Royal College of Surgeons. Running from his hairline to his eyebrow (half of which has been shaved off) is an insane Ahabian scar – as if he’d been struck by lightning – a zigzag rip which left a flap of skin dangling in front of his already blind eye, exposing his skull.

This living Nelson is a damaged, emaciated, asymmetrical crash. As the skin fell over his face during the battle, blood pouring into his eyes, he collapsed into the arms of Captain Edward Berry and was carried below, crying, ‘I am killed, remember me to my wife,’ and calling for his chaplain. Stitched by the ship’s surgeon in dim light, the repair is not an invisible one. Any dandy would have reprimanded his tailor for such work.

Nor was it the first time he had nearly died. In an expedition to the Arctic as a fifteen-year-old coxswain, Nelson had leapt onto the ice to shoot a polar bear whose pelt he wanted as a present for his father. In the legendary scene, he discharged his weapon, missed, and only a chasm opening up between him and the beast preserved him. ‘Never mind,’ Southey had him say; ‘do but let me get a blow at this devil with the butt-end of my musket, and we shall have him.’ Nelson was, said Southey, feeble in body but affectionate in heart. In India he fell victim to a disease which defied diagnosis and left him ‘reduced almost to a skeleton’, unable to use his limbs. In the Caribbean, having avoided being bitten by a venomous snake, he drank poisoned water that left ‘a lasting injury upon his constitution’ according to his doctor; perhaps he was a victim of the same vodou which poisoned Bro’s moonlit dolphin. He then contracted dysentery, which rendered him so helpless that, like Elizabeth, he had to be carried to and from his bed, ‘and the act of moving him produced the most violent pain’. Even his family seemed prone to dramatic tragedy: in 1783 his sister Anne ‘died in consequence of going out of the ballroom at Bath when heated with dancing’.

Nelson was so attuned to his own mortality that he had a coffin set upright in his cabin behind his dining chair. He was forever rehearsing his noble fate, falling and rising and falling again. He was one long wreck. The year before the Battle of the Nile, when his arm was smashed by a musketball at Tenerife, he told his sixteen-year-old stepson Josiah standing next to him, ‘I am a dead man.’ After it was amputated, his arm reappeared as a phantom limb: feeling his own ghostly fingers pressing into his palm, Nelson declared he’d discovered ‘direct evidence of the existence of the Soul … For if an arm can survive annihilation why not the whole person?’ In Moby-Dick, as he lies sleeping with Queequeg’s arm around him, Ishmael is scared by the childhood memory of his sleep-deadened hand; while Ahab, feeling the tingle of his own lost leg, muses on the absence: ‘How dost thou know that some entire, living, thinking thing may not be invisibly and uninterpenetratingly standing precisely where thou standest; aye, and standing there in thy spite? … And if I still feel the smart of my crushed leg, though it be now so long dissolved; then, why mayst not thou, carpenter, feel the fiery pains of hell for ever, and without a body? Hah!’ The age invented Nelson: a Creature of his constituent parts; or already a resurrected god, as Blake saw him.

Amy and Louise are busy on the other side of the room. Working a sort of windlass, Amy opens up a floor-to-ceiling unit and, with Louise’s help, takes out three white body-length bags, one after the other. Carrying them as carefully as orderlies might lift a patient or a cetologist a dead porpoise, the two women lay them on the table. One by one, their shrouds are unwrapped for my benefit.

Out of that bright whiteness, in the fluorescent-lit laboratory interior, the god is revealed in wool and thread and metal. The intense, almost black navy cloth is revealed under the kind of light it would never have seen in its occupant’s lifetime, its lustrous darkness enhanced by rows of gold buttons two centuries have failed to dull. The mattness of the material, which lies so flat, is heightened by these gilt bursts. It is in these contrasting qualities that the essential power of these garments lies. Over the next two hours we talk over the three coats like doctors at a bedside, moving from one to the other as our assessments are made. Every detail, every loop of gold thread, every delicate stitch is discussed and diagnosed as we admire artefacts as finely engineered as any ship of the line.

Opening up the first – the undress coat worn by Nelson at the Battle of the Nile, as seen by Melville and Hawthorne two centuries ago – Amy shows me the fine linen lining, darkened at the neck and lower down by rusty brown stains. Nelson’s blood, she says matter-of-factly, even though she is as aware as Hawthorne, her fellow American, was of the ritual power of those words. Flipping the coat over with Louise’s help, like a nurse administering a bedbath, Amy points out a greasy horizontal smear on the back, just below the collar. It is the tideline of Nelson’s pomade, left behind as his pigtail brushed back and forth while its owner issued commands and exhortations. This honoured raiment is a grubby, scabby rag, a reminder of the messy business of being human. It would normally be Amy’s signal duty to expel any organic substance from such an important item. Here it is her task to preserve Nelson’s memory and conserve his genetic residue, as if he might at some future point be regenerated when England needed him again.

But then, the cloth itself is impregnated with the subtle oil of Spanish Royal Escurial merino sheep, their fleeces coated with mud which dried en croute to preserve their lanolin, producing wool so prized that English visitors would be taken to see the crusty ruminants as if they were a stop on the Grand Tour, as essential as any Michelangelo statue carved in marble. This fabric, with its threads finer than human hair, absorbed the indigo dye that enabled the colour known as navy blue, advertised in the eighteenth-century press as the patriotic shade to wear in wartime; an austere, deluxe colour, the same deep blue which adorned Beau Brummell’s dandiacal body. Once milled, felted and pressed, the cloth lay so neat and tight that it needed no hems. The raw edges of this coat are just that: raw, still bearing the cut marks of the tailor’s scissors, shaped out of his art with exquisite precision.

History takes over. Nelson steps out from Luzzardi’s canvas, leaving a human hole in the canvas, to lie on the melamine table for our intimate examination. The effect is fixating, sensual; the cloth lies around the admiral’s absent body as a fabric memory, all curves and flaps and seams and pleats. The tailors – Gieves of London, Meredith of Portsmouth – worked late into the night by candlelight focused through glass bulbs, filled with water rather than electricity, to create these miraculous constructions.

There’s a naval strategy to this design: the sweep of the lapel, the rise of the collar, the arch of the pockets; they too contain codes. These are maritime coats, made for the sea, amphibiously adapted from the land and worn with white woollen breeches for warmth and ease of movement. They might be soaked with seawater, but such outfits were never washed. Shoulders would be sponged, breeches brightened with pipe clay; I daresay they’d have stood up of their own accord. The pleated skirts swung as Nelson walked, an echo of the extravagant attire of the macaronis of a generation before. Rather than set or follow fashion, military garb absorbed and slowed it down, incorporating it into its own masculine flash. Any other man covered in such fine cloth and gold lace – cuffs as weighed down with gold thread as any chunk of gold chain – might be regarded as offensively flamboyant. No one could accuse Nelson of that, at least not to his stitched-up face. Yet the implicit swagger of those skirts combined with his torn face, his scars, his missing arm and eye to create an autofact as reconstructed as his vessel; an elegant man of war at home in a salon with his mistress, at a torchlit gothic party thrown by a noble pederast, or on a lurching deck, dealing death. As Amy says, such a costume civilised a hired killer. A murderer in the ballroom.

As we work through the three coats, I continue with my questions, as I would over the necropsy of a cetacean. What is this for, why is this there, what does that mean? Why all this gold thread and silver wire, sequins and shiny green foil, so brilliant and ersatz that they might have been confected from the wrappers of a tin of Quality Street? The three Nelsons laid before us are eloquent of his stature as well as his status: the narrow-cut shoulders, the nipped-in waist, the length of the coat are evidence of a short man, five foot six inches tall. I long to slip my arms in those slim sleeves and feel the skirts sway and bounce like a kilt; to be constrained by its tight chest and back; to be a hero, just for a minute or two. Yet for all the finery of these items, they are overshadowed by one last detail. In each coat, Nelson’s redundant right sleeve – which goes unlined, in a random act of economy – ends in a thin silk loop, fixing the empty reminder of a former skirmish to his coat front; as much a badge of honour as any of the other awards sewn there.

Our audience with the admiral is over. As Amy and Louise fold the clothes like valets returning their master’s attire, I notice a sequin fall out of one coat – a dull tarnished disc, like the scale of a fish or a lizard’s eyelid, a bit of stardust. I consider licking my finger and dabbing it up as an illicit memento. Instead, I do my duty and point it out to Amy, who tucks it back into the cloth. The coats vanish back into the collection. The unit rolls to a close with a click, and we sign out of the building.

In old age, Melville’s youthful trips to Greenwich and Portsmouth came back to haunt him. They were the holding places for his last story, as if he had been saving them up. His visits to those ports, which had precipitated the triumph and failure of his great white whale, rushed back like a late tide. With them they brought the body and soul of the Handsome Sailor, washed ashore at his feet.

Billy Budd is a work of poetry only pretending to be prose. It was written as an elegy from the end of Melville’s life, long since spent on land as a customs inspector on the banks of New York’s East River. It is a melancholy, beautiful tale, seen through his personal, and a greater, history; the momentous century he lived through, yet which in many ways passed him by. Melville was always at sea, in his head. You could see it in his eyes, as if the ocean pooled in them, as if his eyes had become the sea.

In his 1923 essay on Herman Melville, D.H.Lawrence saw the American as ‘the greatest seer and poet of the sea’, ‘half a water animal … a modern Viking’. He had, said Lawrence, ‘the strange, uncanny magic of sea-creatures, and some of their repulsiveness. He isn’t quite a land animal. There is something slithery about him. Something always half-seas-over. In his life they said he was mad – or crazy.’ He was the outcast and the sensor, like Thomas Jerome Newton, Martin Eden, and Jay Gatsby, a lost, lone figure, all at sea. ‘For with sheer physical vibrational sensitiveness, like a marvellous wireless-station, he registers the effects of the outer world … of the isolated, far-driven soul, the soul which is now alone, without any real human contact.’

And Lawrence saw it in his gaze, his pale blue eyes that took in too much light. ‘There is something curious about blue-eyed people … something abstract, elemental,’ he concluded. ‘In blue eyes there is sun and rain and abstract, uncreate element, water, ice, air, space, but not humanity … The man who came from the sea to live among men can stand it no longer … The sea-born people, who can meet and mingle no longer: who turn away from life, to the abstract, to the elements: the sea receives her own.’

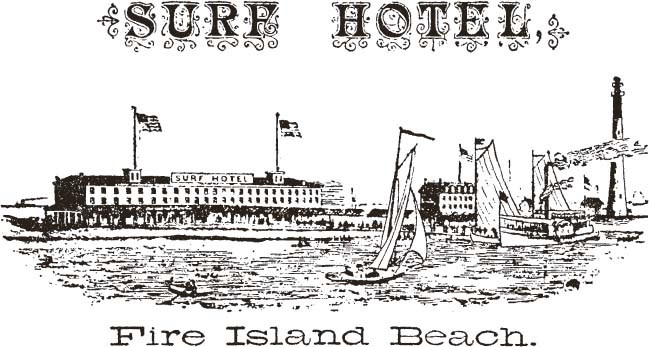

From his exile on East 26th Street, in a dark townhouse where his granddaughter would recall the fright of seeing a bust of Antinous covered by a veil to keep it from Manhattan dust, Melville escaped for Fire Island. He stayed there with his family in the Surf Hotel, which advertised itself as the only establishment at whose ‘very doors you may revel in the sand or sea’ and enjoy ‘all the beneficial effects of the Ocean, without the discomforts of a sea voyage’. Melville worked on Billy Budd in his room overlooking the ocean: the same shore where Wilde had swum, where Thoreau searched for Margaret Fuller, and where Auden and Isherwood would dally, too; a fractured, queer coast, a halfway place like Provincetown, between here and Manhattan and the open Atlantic.

His memory was stirred not only by the sea, but by what had happened to his own cousin. As a junior officer in the US Navy, Guert Gansevoort had been party to the conviction of a young sailor, Philip Spencer, hanged for mutiny in 1842. Gansevoort had done his duty, but he was haunted by the episode for the rest of his life. Drawing on this family remembrance, Melville dived into his books like a library cormorant, reading Southey’s biography of Nelson and accounts of notorious naval mutinies. Looking back to an era that ended just before he was born, he invested the sadness and splendour of his life in the fate of a blue-eyed sailor. His story was simple, like Billy himself; but it had all the power of a parable.

1797. The Royal Navy, busily engaged in fighting the Napoleonic Wars, is threatened by the enemy within. There are mutinies at Portsmouth and the Nore on the Thames estuary, sparked by the spirit of the French Revolution. Anarchy is about to be imported to British shores. There’s an apocalyptic vibration in the air.

William Budd, sailing from Bristol, is impressed in the Narrow Seas off the English coast. He is seized from his merchantman, Rights of Man (named after Thomas Paine’s revolutionary text), and brought aboard HMS Bellipotent, commanded by Captain Edward Fairfax Vere. Billy, beloved of the ship from which he is taken, becomes the darling of the ship he joins. His besotted shipmates do his washing for him and darn his trousers; they all but swoon, and the carpenter makes him ‘a pretty little chest of drawers’, much as if they might set up home together. His perfection has only one flaw: a speech impediment which gets the better of him at moments of crisis. For all his beauty, Billy is as fated as the Ancient Mariner; his stammer is his albatross.

As his powerful allure is transferred to Bellipotent – from the civilian to the military – Billy’s charm quells all quarrels. But his popularity is a challenge to John Claggart, the master-at-arms – the ship’s policeman. Affronted by a beauty he cannot possess, Claggart frames the Handsome Sailor as a scheming mutineer. He bribes an afterguardsman (the name is not coincidental) to meet Billy in the lee forechains, one of those secret places in the ship, and proposition him with sinful insurrection. Billy responds violently, stuttering, his honour outraged. But his innocence has been tainted. Confronted by Vere and accused by Claggart, Billy’s defect becomes fatal. Asked by the captain if this claim is true, the sailor’s stammer leaves him tongue-tied, unable to deny the charge. And as words fail him, Billy uses his fists. He lashes out at his accuser; Claggart falls to the floor, accidentally killed by the blow.

The drama of the story lies in the meeting of these three men, these three symbolic powers. Vere, an introspective, educated man, perpetually looks out to sea, as if he might find the answer to some unexpressed question there. He is respected by his crew as a man who will lead them to victory against the enemy. Yet he lacks Nelson’s common touch; like Billy, whom he loves like all the rest, he is failed by his powers of communication. He cannot engage with his men, other than on an airy level – hence his nickname, Starry Vere, drawn by Melville from a poem by Andrew Marvell. Unlike Moby-Dick’s Starbuck, whose name implies the sky secured, Vere’s underlines his aloofness. Claggart too is detached and foreign, with his strange ‘amber’ complexion and uncertain background: there are hints that the master-at-arms may be fleeing some episode in his past. He is neither officer nor seaman; a disappointed man, a manipulator, a villain: all these we read into his brutal name. Like Ahab, he is the personification of impotent rage. In the 1962 film of Melville’s book, as watched by Newton in his apartment, Claggart declares, ‘The sea is calm you said. Peaceful. Calm above, but below a world of gliding monsters preying on their fellows. Murderers, all of them. Only the strongest teeth survive. And who’s to tell me it’s any different here on board, or yonder on dry land?’

Filled with signs and wonders, told slowly as if he had all the time in the world, yet shortened where Moby-Dick was long, Melville’s tale takes on the tone of another last work, The Tempest. With its ritualistic sparseness, it too could be played silently, in the way Britten’s operatic version of Billy’s story replaces words with music. Characters become types: Vere is removed from the natural world, too philosophical and internalised to see it; Claggart stands over the darkness, at the edge of the abyss; Billy is beyond them both, a natural child, his only flaw echoed by his own alliterative, childish name which stumbles over itself. He is eager to please and to report for whatever duty his masters demand of him, unquestioning, like a loyal dog.

Not that there is any time left for questions. Starry Vere knows Billy to be innocent, but the king’s justice requires retribution: ‘Struck by an Angel of God. Yet the Angel must hang.’ Hoisted from the yardarm by his own shipmates, Billy dies crying, ‘God bless Captain Vere.’

At the same moment it chanced that the vapory fleece hanging low in the East was shot through with a soft glory as of the fleece of the Lamb of God seen in mystical vision, and simultaneously therewith, watched by the wedged mass of upturned faces, Billy ascended; and, ascending, took the full rose of the dawn.

Out of the silence that follows, a murmur of insurrection rises from the assembled crew – the very reaction this punishment sought to forestall. The swelling protest is arrested by the silver whistles of the officers, a sound as shrill as a sea hawk. Billy’s virginal body, hanging as a ‘pendant pearl from the yardarm-end’, is unsullied by the ejaculation experienced by other executed men (while Starry Vere stands watching, ‘erectly rigid’). He is then sewn into his own hammock and, weighed down with lead shot, tipped into the deep in a fulfilment of his song, an echo of Ariel’s, and Jonah’s: ‘Fathoms down, fathoms, how I’ll dream fast asleep … Roll me over fair! | I am sleepy, and the oozy weeds around me twist.’

Where Icarus fell into the water, burnt by the evening sun, the rose-tanned Billy rises with the morning sun, before being lowered to the deep. The sea hawks circle over the spot, so near the ship that the crew can hear the crack of their wings and the ‘croaked requiem’ of their cries. And as Ahab is dragged down by the whale, and Ishmael bobs up out of the whirling maelstrom, clinging to Queequeg’s coffin, rising from the dead like Lazarus, Billy’s innocent body is hoist to the sky then consigned to the sea, both condemned and resurrected.

Twentieth-century critics noted that Melville had read Matthew Arnold’s On the Study of Celtic Literature and other accounts, and shaped his sailor out of Beli or Budd, the Celtic sun god of glorious death. Billy is a golden talisman found in the sea, miraculously untarnished. He is part god, part animal – the word victim signifies a beast for sacrifice – just as Lawrence, writing about Moby-Dick, saw Jesus the Redeemer as Cetus the Leviathan. ‘Everything is for a term venerated in navies,’ Melville writes at the end of Billy Budd. He tells us that the spar from which the Handsome Sailor hung is passed as a relic from ship to dockyard by sailors to whom ‘a chip of it was as a piece of the Cross’.

There is a third and final death in this trinity. In an epilogue, Captain Vere is struck on deck by an enemy musketball. The ritual is complete. And as he lies dying, in an opiated stupor, Vere mumbles not ‘Kiss me Hardy,’ nor even ‘God bless the King,’ but ‘Billy Budd, Billy Budd.’ It is not an expression of remorse.

Lodged in the archives at Harvard is the manuscript of Billy Budd. It is as much-patched as Billy’s trousers, its pages still pasted and pinned together, evidence that Melville revised his work ever more urgently, as if fearful that the story might grow to the length of Moby-Dick, yet knowing he had little time left in which to accomplish it. Racing across loose sheets of laid paper, Melville’s open and slanting longhand – forever catching up with itself – allows for fewer than one hundred words to a page, even as it expands to a novella; while the date, added to the top of the first page – ‘Friday Nov. 16. 1888. Began’ – begs an ending, perhaps his own.

Melville was nearly seventy by the time he came to write Billy Budd. His eyesight, never strong, was failing, and he was ever more ‘the occasional victim of optical delusion’. (When I meet his great-great grandson, Peter Gansevoort Whittemore, in New Bedford, shaking his Melvillean hand and looking into his pale blue eyes, he tells me that the family’s only relic of the writer was a pair of his thick spectacles.) Perhaps that was what fed his imagination, those eyes that had seen too much. He was plagued by the memory of his son Malcolm, who had shot himself in his bedroom at East 26th Street with a pistol he kept under his pillow; his other son, Stanwix, had died of consumption in a San Francisco hotel.

In these tragedies of children who had predeceased him, this Daedalus held his invention to himself, unwilling to let it go. Billy Budd, as pure and provocative as it is, is suffused with regret and glory. It has a double power, since it was not published for forty years, long after its creator made careful corrections and pastings and pinnings and crossings-out, each scissored slip subtly swelling its reach. Alluding to the love of the crew of the Rights of Man for their Handsome Sailor, Melville notes that they would even ‘darn the seat of his old trousers for him’, a line which he amended, perhaps because it gave too much away. Yet he hardly reined in the homoeroticism of his hero, whose entrance is announced by the impressing officer, suitably impressed himself: ‘Here he comes; and, by Jove – look at him – Apollo with his portmanteau!’ The author’s love of double-entendre had not left him.

And if Billy Budd is a kind of folk hero, all but stitched onto a scrap of cloth or carved into a bit of whale bone, there’s an odd naïveté to his creator: the bawdy sailor turned autodidact like Shakespeare, for whom the whale ship was his Harvard and Yale. Melville’s writing, even now, at the end of his fitful career, had an unconstrained innocence and a coded knowingness, one which was let loose yet made more mysterious by the sea – like Billy himself. His story’s subtitle – ‘An Inside Narrative’ – admits as much, as if he were caught between Elizabeth Barrett Browning, whose works he avidly read, and Virginia Woolf, who avidly read his works; the same prophetic quality which would cause Lawrence to declare Melville ‘a futurist long before futurism found paint’.

The revisions and replacements and parentheses, the attached flaps and sliced scraps of stray words and gathered phrases play with the past and the future like the starman’s cut-ups, adding layer upon layer, harnessing a fleeting memory while achieving exactly the opposite effect. Supposedly taken from a broadside published in Portsmouth, Billy’s story might as easily appear in Lascar, or a novel by Genet or Burroughs, in The Tempest or on Mr Newton’s TV screens. There’s something of its innocence in The Great Gatsby, published the year after Billy Budd, whose hero is called ‘a son of God’ and dies outstretched on his pneumatic mattress-coffin, floating in his pool, ‘the holocaust complete’; while at the end of the century, in her film Beau Travail, Claire Denis would reset it in the Horn of Africa, where the sea becomes the desert and the sailors foreign legionnaires, performing a brutal, bare-chested ballet, choreographed to a soundtrack from Britten’s opera.

As much as he covered his traces, Melville laid flagrant clues for future readers. If the published text – which he would never see – wasn’t enough of a giveaway, the manuscript betrays its intentions in its written hand. For page after page he rhapsodises over the elusive Billy, spilling words in his direction. He lovingly evokes ‘a lingering adolescent expression in the as yet smooth face all but feminine in purity of natural complexion’, the sort of boy Owen met on English beaches; a boy ‘cast in a mould peculiar to the finest physical examples of those Englishmen in whom the Saxon strain would seem not to partake of any Norman or foreign other admixture, he showed in face that mild humane look of reposeful good nature which the Greek sculptor in some instances gave to his heroic strong man, Hercules’. He lingers over Billy’s body like a movie camera, ‘the ear, small and shapely, the arch of the foot, the curve in mouth and nostril, even the indurated hand dyed to the orange-tawny of the toucan’s bill, a hand telling alike of the halyards and tar bucket; but, above all, something in the mobile expression, and every chance attitude and movement’. And he constantly underlines the phrase the handsome sailor. The effect is similar to the cinematic manuscript of Frankenstein, in which Shelley replaced his wife’s description of the Creature as handsome with the word ‘beautiful’.

Melville was making all these things up, even as he drew on Celtic myths and naval legends. Billy has no precedent; we do not know where he comes from, nor does his creator. When asked where he was born, Billy replies brightly, ‘God knows, sir,’ adding only that he was found as a baby ‘in a pretty silk-lined basket hanging one morning from the knocker of a good man’s door in Bristol’. The words ‘pretty silk-lined’ have been added afterwards, in an improbable detail reminiscent of Stephen Tennant’s tough sailors and their unlikely interest in ribbons, while the officer’s response is worthy of Wilde: ‘Found, say you?’

Suffused as he is with strength and beauty, possessed of comeliness and power, Billy is primal and animal, and ‘Like the animals, though no philosopher, he was, without knowing it, practically a fatalist.’ And if no animal suspects its own mortality, neither does he. ‘Of self-consciousness he seemed to have little or none, or about as much of it as we may reasonably impute to the animal creation an intelligent mastiff a dog of Saint Bernard’s breed.’ Billy is with the beasts; he is wild, but ends up in chains. Like a bird, ‘he could not read, but he could sing, and like the illiterate nightingale, was sometimes the composer of his own song’. He stutters like a bird, too. He is the Lamb of God, an animal sacrifice. But he is also a natural force, a noble savage, a foundling: Melville compares Billy – known as Baby Budd – to Kaspar Hauser, a lost boy; but he could be Peter Pan or Mowgli. In early drafts, Melville seemed to indicate that his Handsome Sailor was black, a conflation of the Trafalgar veteran at Greenwich and another memorable sailor he’d seen in Liverpool on his first visit to England in 1839:

The two ends of a gay silk handkerchief thrown loose about the neck danced upon the displayed ebony of his chest, in his ears were big hoops of gold, and a Highland bonnet with a tartan band set off his shapely head. It was a hot noon in June; and his face, lustrous with perspiration, beamed with barbaric good humour. In jovial sallies right and left, his white teeth flashing into view, he rollicked along, the center of a company of his shipmates.

A black Billy would have been a wondrous cynosure, in the true meaning of the word, from the ‘dog’s tail’ North Star, the star around which all the others revolve. But our Billy moves among his mates like another luminary, ‘Aldebaran among the lesser lights of his constellation … A superb figure, tossed up as by the horns of Taurus against the thunderous sky.’ His heavenly body is the summation of his creator’s desires. And whether golden Adonis or dark star, human or animal, what was certain was Billy’s perfection, confirmed by a single fault, like Byron’s club foot. ‘Though our Handsome Sailor had as much of masculine beauty as one can expect anywhere to see; nevertheless … there was just one thing amiss in him.’ Billy’s stammer belies his gender, yet he is made almost asexual by his innocent beauty.

In 1828, Robert Dickson, a ship’s surgeon on HMS Dryad serving in the Mediterranean, noted a remarkable case in his logbook. He described eighteen-year-old Samuel Tapper, one of the able-bodied seamen, as having a ‘brown complexion – an active and hardy lad’. But Tapper had a secret, hiding in plain sight. ‘I had frequently requested to observe this lad (who is an excellent swimmer) bathe with the other boys,’ Dickson wrote. ‘Tapper’s breasts so perfectly resemble those of a young woman of 18 or 19 that even the male genitals which are also perfect, do not fully remove the impression that the spectator is looking on a female.’

It was as if Darwin had fished a merman out of the Med; this intersexed sailor sporting like a dolphin, an Orlando in mid-transition, or even some new species in the process of evolution. There is more than a little voyeurism in Dickson’s observations. Having watched from afar as the boy bathed with his mates – who appeared to ignore Sam’s ‘curious formation’ – Dickson gained access to this alien body when Tapper was brought into the sickbay. On close examination, the surgeon discovered that the young sailor’s breasts were glandular, ‘not at all resembling the fat mammille of boys’. Dickson deliberated, in an objective, Enlightenment manner on the cultural context for his interest, evoking Shelleyan images of marriages of male and female, and a magical ability to change shape. ‘I have been chiefly moved to notice this case,’ he wrote, ‘having lately seen in the Royal Gallery at Florence the statue of an Hermaphrodite, (so called) perfectly resembling Tapper, in breasts and genitals.’

Melville was always romantically drawn to transformation. He saw Billy’s imperfection as ‘an organic hesitancy’, an ambivalence in a story which, like Moby-Dick, is filled with strange undercurrents and digressions. But it was also by way of reassuring the reader that Billy’s fate drew on hard fact: the threat of violent subversion against the leviathanic state and what the true rights of man might be.

The Great Mutiny of 1797 had shocked Britain with its ‘unbridled and unbounded revolt’, more menacing than all of Napoleon’s armies of the Antichrist. The ordinary sailor had become the enemy within. Off Portsmouth’s Spithead, the crew of Royal George rebelled, demanding better food – vegetables with their beef instead of flour – as well as pensions to Greenwich. These were denied. One admiral, Gardner, was so incensed by the petitions – including one requesting absolute pardon for their actions – that he ‘seized one of the delegates by the collar, and swore that he would have them all hanged, together with every fifth man in the fleet’. The mutineers responded by hoisting the red flag. On London, Marlborough and Minotaur, sailors refused to go to sea; when they raised their guns, their officers opened fire, killing five men and seriously wounding six others.

By now the unrest had spread to the Thames. The men of HMS Sandwich seized control of their ship at the Nore anchorage, south of Sea Reach, the wild point at which the river became the sea, past which Melville himself would sail, unable to write his journal for the ‘jar & motion’ of the ship. The mutineers’ ringleader was Devon-born Richard Parker, an educated man who had previously challenged his captain to a duel. (He was also a man ominously christened, this Richard Parker, slipping in and out of history, from the fictional Richard Parker of Poe’s Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, published in 1838, a cabin boy who is eaten by his shipwrecked mates, to the real-life teenaged Richard Parker of Southampton who met the same fate in 1889.)

Under Parker’s brief leadership, the Nore insurrectionists made avowedly political statements. They demanded the dissolution of Parliament and immediate peace with France. Theirs was a maritime utopia, proposed on the same stretch of sea-river where Frank Harris had offered Wilde his freedom, the shore from which Oscar might have set sail for his own utopia, or where Shelley might have floated his anarchist fleet. Physically achieving what the poets had tried to do with words, the mutineers’ Floating Republic was a direct challenge to the landbound state: they blockaded the venal capital, threatening its lifeblood of trade. The authorities responded by stopping their own food supply.

The mutiny failed. Parker tried to take the fleet to France, but his supporters deserted him. Arrested, tried, and sentenced to swing from the yardarm, Parker declined a white hood and jumped off before he could be hoisted, breaking his own neck. Far from becoming a martyr like Billy, his body was displayed in a tavern for a week to discourage further dissent.

But such grim tactics did not seem to be working. As the Nore and Spithead mutinies got under way, the insurrection spread to Parker’s native Devon. In Torbay, two mutineers, William Lee and Thomas Preston, were hanged from the yardarm of Royal Sovereign, signing off their dramatic death letter, ‘We who this morning are doomed to bid adieu to this World … launched into the Gulph of Eternity.’ Their bodies were put into coffins drilled with holes and sunk off Berry Head (only to be later retrieved by Brixham fishermen and respectfully buried on land). And at nearby Plymouth, the third centre of Britain’s maritime power, two sailors on HMS St George were sentenced to death for sodomy. A deputation came to the quarterdeck to ask the captain, Shuldham Peard, to intercede on the condemned men’s behalf. But Peard was warned by two men who slipped into his cabin that the crew were close to mutiny. He had four men court-martialled and hanged that Sunday, despite protests at the profanity. (Nelson said he would have hanged them on Christmas Day.) Ten years later in the same port, William Berry – Billy Berry – described as ‘above six feet high, remarkably well made, and as fine and handsome a man as in the British Navy’, was hanged for sodomy.

All these bodies paid the price extorted by the state. Melville made no direct reference to such injustices, but his work is full of them; nowhere more so than in the starry innocence of Billy Budd. In the body and soul of the Handsome Sailor, he looks beyond law and the ordinary world, to a place where we might all be set free.

The manuscript of Billy Budd was found, not in a basket but a bread box – along with Melville’s note to himself, ‘Stay true to the dreams of thy youth’ – thirty years after its author’s death in obscurity in New York. The book was dedicated to Melville’s long-lost English friend Jack Chase, ‘Wherever that great heart may now be, Here on Earth or harbored in Paradise’. And it was left to England to resurrect Billy, as if he were a twentieth-century boy. When it appeared in 1924, the story alerted D.H.Lawrence, Virginia Woolf, E.M.Forster and W.H.Auden to Melville’s startlingly modern writing. In his collection Another Time – published in America in 1940, the same edition which included his hymn to Icarus, ‘Musée des Beaux Arts’ – Auden reimagined Melville. He saw him in those last years, his beard greying, his blue eyes failing, sailing into ‘an extraordinary mildness’. Mindful of his own time, Auden – who owned a shack on Fire Island where, unbeknown to him, the Handsome Sailor had taken shape from the sea – wrote that ‘Evil is unspectacular and always human,’ while goodness ‘has a name like Billy and is almost perfect | But wears a stammer like a decoration’.

A decade later, in 1950, Benjamin Britten’s Billy Budd appeared during a new era of fear. In New England during the McCarthyite purges, Newton Arvin, the Scarlet Professor who taught Melville to Sylvia Plath at Smith College and whom Truman Capote, his lover, called ‘my Harvard’, would be prosecuted when images of naked men were found in his office. For Britten, as for Forster, his librettist, and Auden, their friend, Melville’s writing was an eternal, subversive response, embodied in the otherness of the sea. His opera subtly altered Melville’s story. Its oppressive setting and impressed men evoked the recent trauma of war and fears of a nuclear world in which terrible new weapons were detonated in remote oceans. As his crew toil and sing ‘We’re all of us lost forever on the endless sea,’ so Starry Vere echoes their words with his own: ‘I have been lost on the infinite sea.’

Falling and rising and falling again, they’re all lost, these unmothered men and boys, abandoned to their fate like poor beautiful Billy, like Ishmael, like their blue-eyed creator.

All of them lost forever on the infinite sea.