8

Basics of Parallel Programming

Today, almost all computer systems, including embedded and mobile systems, are equipped with multicore microprocessors – not to mention graphics programming units (GPUs), which are equipped with thousands of cores. However, all the programs we have written and analyzed until now perform sequentially. That is, although we have multiple functions and calls between them, a microprocessor sequentially processes only instruction at a time. This does not seem like the most efficient way to use the available hardware resources. Before we go into detail, let's summarize the main topics we will learn about in this chapter:

- Basic concepts of parallel computations

- What concurrent multitasking and threads are

- The risk of using shared objects, and how to protect their access

- How to make standard algorithms like

std::transform,std::sort, andstd::transform_reduceoperate in a parallel mode - Programming asynchronous tasks with

std::future - Basic construction of the OpenMP library – e.g. how to launch and synchronize multiple tasks, and how to make

foroperate in parallel to significantly speed up matrix multiplication

8.1 Basic Concepts of Parallel Computations

Since an example is better than a hundred words, let's start by analyzing the behavior of a simple function

Task_0

run simultaneously on two threads (later, we will show what a thread is and how to make code run on multiple threads). Let's also assume that

Task_0

accesses a global variable

x

. The situation is outlined in Figure 8.1.

After launching the two threads, each running the same

Task_0

, the output may look like the following

or it may look totally different. On five threads, the output may look like this:

Figure 8.1 An example of parallel execution of two tasks that access the same global object

x

. Since each instruction for each task can be executed at any time and simultaneously, the results of such free access are unpredictable and usually wrong. The way out of this problem is to make all lines that access common shared objects protected, to allow only one thread to execute at a time. Code that needs this type of protection is called a critical section, and the protection can be provided using synchronization objects such as a semaphore or a mutex.

More often than not, the results are incorrect and different from run to run. Such a situation is called a race condition or a hazard. In such a case, we would be lucky to diagnose the incorrect output, since this issue can turn on the red light indicating that something is wrong and needs to be fixed. However, in many cases, errors are stealthy and appear randomly, which makes debugging and verifying parallel code much more difficult.

We have to realize that each instance of

Task_0

runs concurrently. This intersperses the execution of

Task_0

's sequential instructions with the execution of analogous instructions, but in different instances (threads). So, for example, an instance run by thread 0 finishes executing line [3], after which thread 5 is faster and manages to execute lines [3–6] of its code. This changes the common object

x

. If thread 0 now gets its portion of time and executes line [6], the values of

x

and

loc

will be far from what is expected and usually random. Also, the expression on line [8], whose intention was to display the two values, is not atomic. That is, its execution can be partitioned between different threads that happen to execute this code at more or less the same time, which leads to haywire output.

There is nothing wrong with

Task_0

itself. If run sequentially – for example, in a

for

loop – it produces correct results that can be easily verified. This simple experiment should alert us that entering the realm of parallel programming can be like entering quicksand. Of course, this is the case only if we are not careful. Knowledge and conscious software design are the best protection measures.

The broad domain of parallel programming is gaining in importance and popularity. Providing more than an introduction is outside the scope of this book, but we can recommend many resources (Pas et al. 2017; Fan 2015; Schmidt and Gonzalez-Dominguez 2017). The intention of this section is to show that with a few new techniques and carefully analyzed cases, writing simple parallel components in C++ is not that difficult. The gain is worth the effort – as we will see, one additional line of code or a single parameter in a function can instantly make our code perform a few times faster than its sequential counterpart. This is in the spirit of C++, which also means better performance.

Before we show these techniques, we will briefly explain the most important concepts related to the domain of parallel programming:

- Task, multitasking – A procedure, function, etc. to be executed. Multitasking usually refers to the concurrent realization of multiple tasks

- Thread, multithreading – A thread is a separate path of code execution. It can be seen as the code and computer resources necessary to perform a task. Multithreading means the ability to run multiple threads concurrently. Threads can be executed by a single core or multiple cores of a processor. A single core can also run one or more threads by means of the OS's thread-preemption mechanism: a thread can be preempted at any moment and put into the queue of waiting threads; it can be then resumed by the OS as the result of an event, a specific condition, elapsed time, etc

- Thread pool – A group of pre-created threads that wait to be assigned to tasks for a concurrent execution. Maintaining a pre-created pool of threads increases performance by avoiding time-costly creations and deallocations of threads, but at a cost of increased resource usage. Once created, the pool of threads is usually maintained until the last parallel region is executed in the program

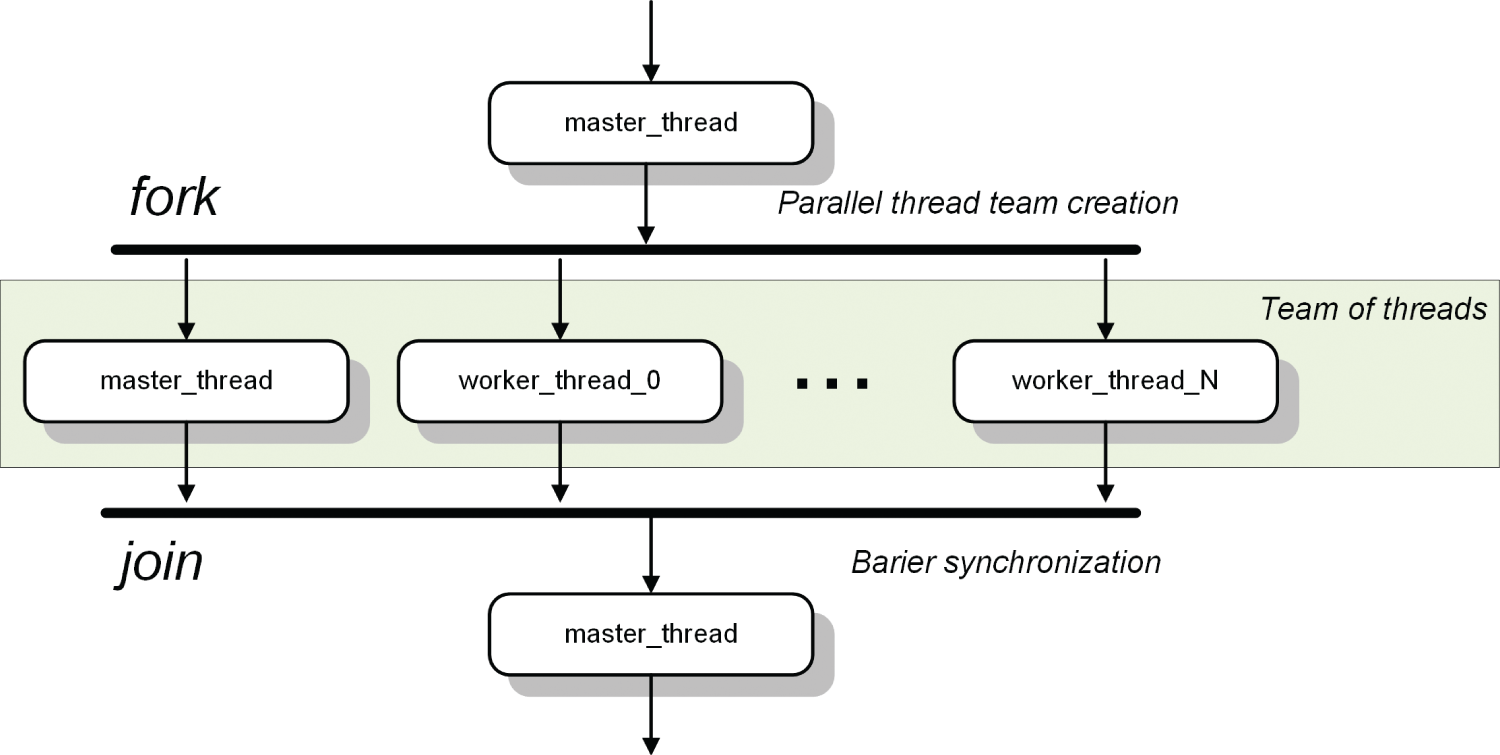

- Team of threads – A group of threads for work sharing inside a parallel region. One of the threads is appointed the master and the others are worker threads, as shown in Figure 8.2. The process of spawning multiple threads is sometimes called a fork. When threads meet at a common point, this is called a join (i.e. they are synchronized)

Figure 8.2 UML activity diagram showing the launch of a team of threads.

- Concurrency – The simultaneous execution of multiple tasks/threads

- Shared objects (resources) – Resources (objects) that can be accessed concurrently by many threads. If a resource can be changed by any of the threads, then special protection techniques should be used to allow access by only one thread at a time, to prevent hazardous results

- Private objects (resources) – Resources (objects) that are entirely local to a task/thread and to which other threads do not have access (e.g. via a pointer, etc.); Private objects do not need to be protected for exclusive access since each thread has its own copies

- Critical section – Part of the code in a task/thread that accesses a shared object and should be protected to ensure exclusive access of only one thread at a time

- Mutual exclusion – A mechanism that allows only one thread to execute uninterrupted its critical section. This is achieved by applying an available thread synchronization object

- Deadlock – An error situation in which threads wait for each other to unlock common resources and cannot proceed

- Atomic instruction – An instruction that can be completed by a thread without interruption by other threads. Atomic instructions are used to perform safe access to shared resources

- Synchronization – The process of waiting for all threads to complete. Such a common point of completion is a barrier. Sometimes synchronization refers to the mechanism of providing exclusive access to resources. System mechanisms such as semaphores, locks, mutexes, signals, etc. are synchronization objects

- Thread safety – A safety policy for an object or class when operating in a multithreading environment. A class is said to be thread-safe if, when an object of that class is created that is local to that thread, it is safe to call any method from that object (this is not the case if e.g. a class contains data members declared

staticor that refer to global objects, etc.). An object is thread-safe if it can be safely accessed by many threads with no additional protection mechanism; this means, if necessary, synchronization mechanisms have been implemented in that object

As we saw in this section and the simple example, writing correct parallel code is much more difficult than simply multiplying instances of sequential code. As we may expect, one of the most important aspects is locating and properly protecting all accesses to common, i.e. shared, objects, especially if these are changed by the code. But in practice this can be extremely difficult due to code complexity, which hides common regions and objects. A hint from this lesson is to first take a closer look at all global and static objects. When porting a sequential algorithm into its parallel counterpart, it is also good practice to compare the results of both versions: for example, by writing proper unit tests, as discussed in Appendix A.7.

8.2 Adding Parallelism to the Standard Algorithms

In this section, we will show how to make the standard algorithms perform in a parallel fashion. As we will see, this is easily achieved by adding a single parameter. But we should not do this blindly – as always in an analysis of parallel algorithms, we should identify and protect shared resources to avoid uncontrolled access by more than one thread at a time. However, if there are no shared objects, then many calls to the standard libraries can be treated as separate tasks that can run in parallel. As we will see, adding

std::execution::par

as the first parameter will make this happen.

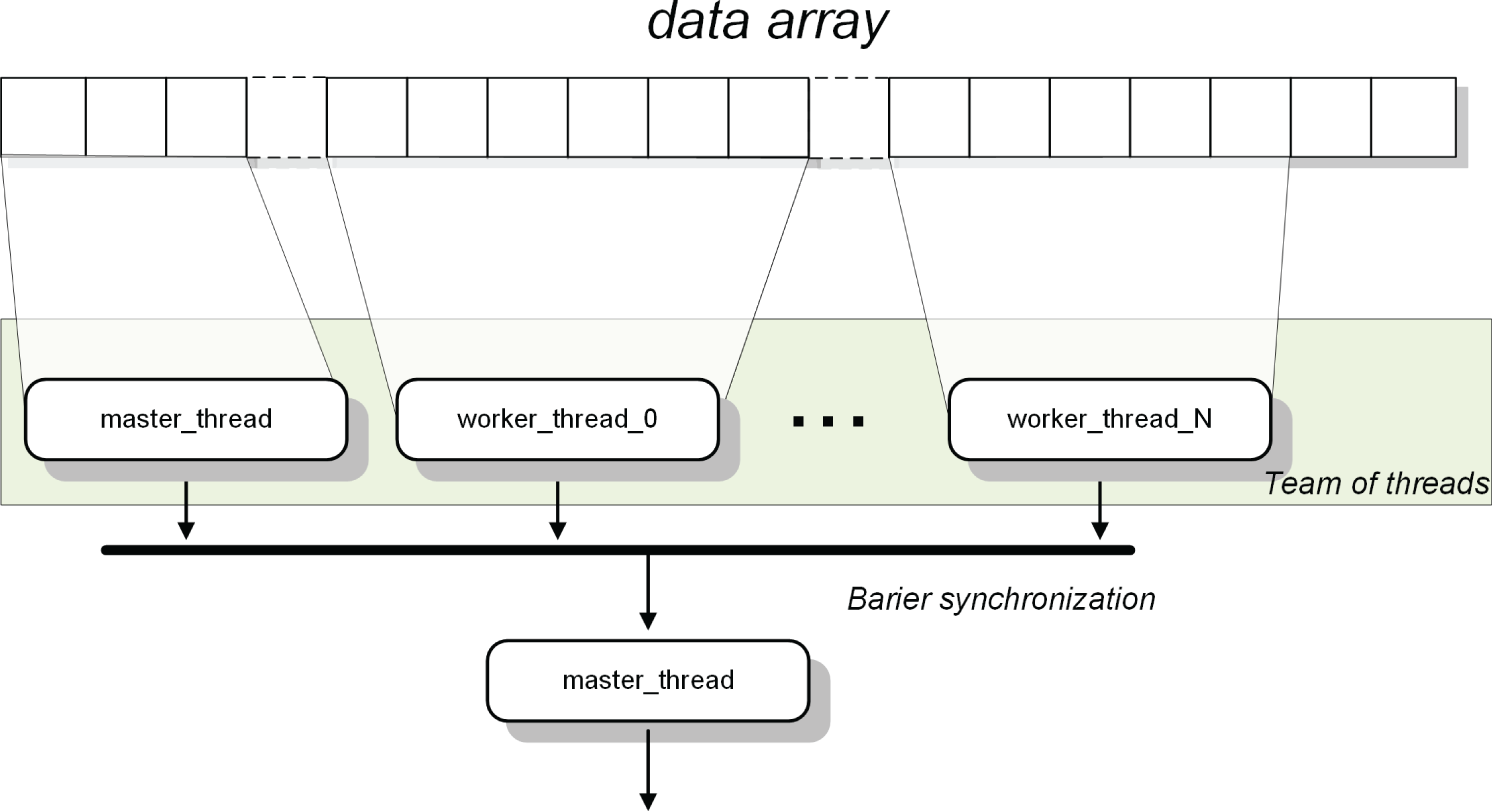

In the following sections, we will build parallel systems based on splitting an initial array of data into a number of chunks that will then be independently processed by separate threads, as shown in Figure 8.3. This methodology is called data parallelism and usually gives good results when processing massive data, such as mathematical arrays, image and video files, etc. We will rely on programming techniques that make this process as simple and error-free as possible.

Figure 8.3 Team of threads operating in parallel on an array of data. Each thread takes its assigned chunk of data. Processing is performed independently in an asynchronous fashion. After all the threads finish processing the entire data array, their common results can be gathered and processed further.

Listing 7.14 shows the

InnerProducts

namespace. It contains three serial algorithms for computing the inner product between vectors (Section 7.4.7). Let's recall their characteristic features:

InnerProduct_StdAlg– Callsstd::inner_productand returns its resultInnerProduct_SortAlg– Creates a vector of individual products between the corresponding elements of the two vectors. These products are then sorted and finally added together. Thanks to sorting, we achieve much more accurate results as compared with theInnerProduct_StdAlgalgorithm. However, sorting significantly increases computation timeInnerProduct_KahanAlg– A version of the accurate Kahan summation algorithm of the products of the corresponding elements of the two vectors

In this section, we will present new versions of the first two functions: they will perform the same action but in a parallel fashion, potentially taking advantage of available multicore processor(s). A parallel version of the third function is presented in the next section.

The first two parallel functions are as follows:

InnerProduct_TransformReduce:Par– Based on thestd::transform_reducealgorithm, which, unlikestd::inner_product, allows for parallel operation. Briefly, transform-reduce is a classical scheme of parallel processing in which a problem is split into a number of smaller problems (transformation) that are then solved, after which the partial results are gathered together (reduction)InnerProduct_SortAlg_Par– A version of the serialInnerProduct_SortAlgthat calls the parallel implementation of the standard sorting algorithmstd::sort

The definition of the

InnerProduct_TransformReduce:Par

function begins on line [11] in Listing 8.1. There is only one expression on line [13], although we have split it into multiple lines for better readability. What is important is the new

std::transform

_reduce

function with the first parameter

std::execution::par

. In our example, it performs the same action as

std::inner_product

; but, unlike

std::inner_product

, it is able to operate in parallel. Going into detail, on line [14] it takes three iterators that define the range of its operation. That is, two input vectors

v

and

w

are element by element multiplied, and these products are added together. This is exactly what transform-and-reduce means – the input elements are transformed in some way (here, they are multiplied) and then reduced to a scalar value, i.e. in our case they are summed. These reduce and transform actions are defined by the two lambda functions on lines [15, 16].

InnerProduct_SortAlg_Par

, defined on line [20], is a parallel version of the serial

InnerProduct_SortAlg

defined in Listing 7.14. Let's compare the two versions. The first difference appears on line [22], as well as in the following

std::transform

. When entering the domain of parallel algorithms,

back_inserter

is the last thing we wish to use. Although it worked fine in the serial implementation, in the parallel world we cannot let many threads back-insert into vector

z

. But the way around this is simple: we only need to reserve enough space in

z

, as on line [22]. Thanks to this simple modification,

std::transform

can operate in parallel and independently with any chunk of data. More specifically, the main difference between the serial and parallel versions is on line [27]. The serial approach uses

back_inserter

. In this version, however, we simply provide an iterator to the beginning of

z

, since it has already been allocated enough space to accommodate all of the results. We don’t need to protect

z

for the exclusive access since each of its elements is accessed only by one thread, whichever it is. Then, on line [31], the parallel version of

std::sort

is invoked. The difference between calling the serial and parallel versions is the presence of the first argument

std::execution::par

.

Finally, the sorted elements need to be summed. In the serial version, we did this with the familiar

std::accumulate

; but it has no parallel version. Instead, we use

std::reduce

, again called with the first parameter set to

std::execution::par

, as shown on line [35].

The only reason we go to all this trouble with converting algorithms to their parallel counterparts is performance. Obviously, the performance time of the serial and parallel versions is the best indicator of success. But in practice, we may be surprised, at least in some of the cases. In the next section, we will show how to perform such measurements and explain what they mean.

We have only scratched the surface of parallel execution of the standard algorithms. The best way to learn more is to read the previously cited resources and visit websites such as www.bfilipek.com/2018/11/parallel-alg-perf.html and https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/algorithm/execution_policy_tag_t.

8.3 Launching Asynchronous Tasks

Still in the domain of the task of efficiently computing the inner product between two vectors, Listing 8.2 shows the

InnerProduct_KahanAlg_Par

function. This is a parallel version of

InnerProduct_KahanAlg

from Chapter 7. But in this case, rather than simply adding the parallel command

std::execution::par

to the standard algorithms, we will go into the realm of C++ multitasking. As we pointed out earlier, task parallelism can be achieved by launching a team of threads that concurrently process the tasks. In this section, we will exploit this possibility.

The definition of

InnerProduct_KahanAlg_Par

begins on line [5]. First, lines [8–14] define the initial control objects. Since

InnerProduct_KahanAlg_Par

performs in parallel, each task is attached to its specific chunk of data, with

k_num_of_chunks

denoting the number of chunks. In practice, data does not split equally, so usually there is some data left. This is held by

k_remainder

. Each chunk of data is then summed independently. Therefore, each result goes to the

par_sum

container defined on line [16]. Also, a summing function is called independently for each chunk of data. Such tasks are easily defined with lambda functions (Section 3.14.6). In our case, this is

fun_inter

, shown on lines [18–19].

The most characteristic part begins on line [21] with the definition of a

std::vector

storing

std::future

< double >

objects. This allows us to define tasks that, after being properly created, can be asynchronously executed. In the loop on lines [25–28], the objects returned by the call to

std::async

with the parameters

std::launch::async

,

fun_inter

, and its local parameters are pushed into the

my_thread

_pool

container. But the tasks are only collected – they are not invoked yet. A similar thing happens on lines [31–34] if there is a remainder.

Line [24] is also interesting: its purpose is to define a variable

i

with the same type as the

k_num_of_chunks

object. So, how do we determine the type of an object given the name of or a reference to that object? Line [24] explains how. First we need to call the

decltype

operator, which returns the type of

k_num_of_chunks

, which is then stripped of any decorators such as a reference, a const, etc. using

std::decay

. Finally, we specify what we are interested in:

std::decay<>::type

.

Let's now return to parallel operations. We have prepared our tasks, which are now deposited in the

my_thread

_pool

container. This way, tasks that are created are invoked in the loop on lines [37–38]. More specifically, the call to

future<>::get

on line [38] launches whatever resources are necessary to execute our tasks. Thanks to our design, these operate independently; hence we were able to use

async

.

Finally, all the tasks finish their jobs – i.e. are synchronized – before the

Kahan

_Sum

function is called on line [40]. Obviously, its role is to sum up all the partial sums returned by the tasks to the

par_sum

repository on line [38].

The lambda function

fun_inter

, on line [18], is based on a serial version of

InnerProduct_KahanAlg

, outlined on line [42]. This is an overloaded version of

InnerProduct_KahanAlg

but with simple pointers defining the beginning of the two data vectors. As a result, the function easily operates with chunks of data that have been allocated in memory.

Next is the most interesting moment – verifying whether all these parallel methods were worth the effort. We ran the serial and parallel versions on a single machine and compared their execution times; the results obtained on our test system1 are shown in Table 8.1.

Table 8.1 Execution times for computing inner products between vectors with 20 000 000 elements each. Three groups of algorithms were tested: simple accumulation, sorting and accumulation, and using the Kahan algorithm. In each case, the timings of the sequential and parallel implementations were compared.

| Algorithm | InnerProd vs. TransRed |

Sort_Ser vs. Sort_Par |

Kahan_Ser vs. Kahan_Par |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serial [s] | 29 | 2173 | 129 |

| Parallel [s] | 12 | 475 | 11 |

| Speed increase | 2.4 | 4.6 | 11.7 |

The most impressive speed increase can be observed for the pair of Kahan-based algorithms. The parallel version outperforms its serial counterpart by more than an order of magnitude! Also, for the algorithms that employ prior element sorting, the speed increases more than four times. This shows that parallel programming is worth the effort. However, in more complex algorithms, an in-depth analysis should be performed in order to spot parts of the code that consume the most processor time. This analysis should be based on measurements and not on guessing. The profiler delivers reliable data to start with, as described in Appendix A.6.3.

8.4 Parallelization with the OpenMP Library

Running parallel versions of some of the algorithms from the SL is simple. But since operations are limited to specific tasks, this mechanism only solves some of the problems involved in implementing parallel systems. We can also design our own threads or run tasks using the ample C++ parallel library (Stroustrup 2013). Doing so has the immediate advantage of building an upper-level interface for the lower-level OS multithreading mechanisms. A correctly designed parallel implementation of the C++ parallel library will work on most modern systems; however, this level of programming requires substantial knowledge, experience, and effort to obtain good results.

The OpenMP library project, which brings us to a slightly higher level of parallel systems programming began in the 1990s. It is aimed at two languages: Fortran and C/C++. It has strong support from the steering committee, and at the time of writing, version 5.0 has been released (www.openmp.org). The most important features of OpenMP are:

- Higher-level programming focusing on tasks that automatically create a team of threads and support synchronization mechanisms

- Operation in a hybrid hardware environment (parallel code can be run on both CPU and GPU)

- Seamless integration with existing C++ code using the preprocessor

#pragma(Appendix A.1). OpenMP code is added in the form of OpenMP directives with clauses. There are also some OpenMP-specific functions

An in-depth presentation of the most important features of OpenMP could consume a book by itself. In this section, we show only a few basic examples. However, they are very characteristic of the common uses of OpenMP, so we can try other parallel algorithms based on them. There are many good sources of information about OpenMP, including the OpenMP web page (OpenMP 2020). A very accessible introduction is Guide into OpenMP by Joel Yliluoma (https://bisqwit.iki.fi/story/howto/openmp). Also, we recommend the recent books by Pas et al. (2017) and Schmidt and Gonzalez-Dominguez (2017). Let's start with a simple example that will demonstrate the basic features of OpenMP.

8.4.1 Launching a Team of Threads and Providing Exclusive Access Protection

The first thing to do when using OpenMP is to add

#include <omp.h>

in the source file, as shown on line [4] in Listing 8.3. The definition of the

OpenMP_Test

function starts on line [8]. Line [13] creates the

outStream

object. This is a string stream to which all output produced by our parallel branches of code will be sent. But we can easily spot that this is a classic example of a shared object. Hence, access to it must be protected to avoid hazards, as will be shown. On line [16], the OpenMP function

omp_get_num_threads

is called. It simply returns the number of threads in the team currently executing the parallel region from which it is called. There is also a counterpart

omp_set_num_threads

function, which lets us set a number of desired threads.

Line [23] contains the first characteristic

#pragma

construction with an OpenMP directive:

omp parallel

says to create and launch a team of threads and to process the following block of code (lines [24–42]) concurrently in each of these threads.

shared( outStream )

explicitly marks the

outStream

object as being shared. However, this does not protect it yet from an uncontrolled access by the threads.

The variable

thisThreadNo

created on line [27] is an example of a private object. That is, each thread contains a local copy. In each,

thisThreadNo

is initialized with the current thread number obtained from a call to the OpenMP function

omp_get_thread_num

. So, if there are 12 threads, the numbers are 0–11. Another local object

kNumOfThreads

on line [30] receives the total number of threads executing the parallel region by calling the previously described

omp_get_num_threads

function (these names can be confusing).

Now we wish to print information about the number of the thread that executes this portion of code, as well as the total number of threads involved. The operation is as simple as using the familiar

std::cout

or

outStream

in our case. However, recall that

outStream

is a shared object and needs to be treated specially: only one thread can perform operations on it at a time, while the others wait. To accomplish such mutual exclusion, on line [36] and again using

#pragma

, we create the

omp critical ( critical_0 )

construction. It tells OpenMP to add a synchronization barrier. As can be easily verified, if

critical

was omitted, the output would be rather messy.2 Then we can be sure that the operation on lines [38–39] is performed entirely by a single thread until it finishes.

Line [42] ends the parallel block, and we are back in the sequentially executed part of the code. So, with no additional commands, on lines [49–50] we can print out the number of threads executing on behalf of this block. Likewise, line [53] prints all the information from the

outStream

object, which was stored there by the threads. Also note that in OpenMP, all thread implementations and manipulations are performed behind the scenes. Therefore it is a very convenient library.

The output of this code can be as follows:

Notice that a total of 12 threads are created in the team and that the critical section is accessed in a random order. But before and after the parallel region, only one thread is active.

An example of an explicit call to the

omp_set_num_threads

is shown on line [58]. If this is omitted, the number of threads in the team will be set to a default value (usually this is the number of cores in the microprocessor).

Also notice that including the omp.h header is not sufficient to use OpenMP in our projects. We also need to explicitly turn on the OpenMP compiler option. For example, in Microsoft Visual C++, we open the project's property pages and under C/C++, Language, set Open MP Support to Yes (/openmp). In the gcc and clang compilers, we set the

–fopenmp

flag in the command line.

8.4.2 Loop Parallelization and Reduction Operations

The next example shows what is probably the most common operation with OpenMP: parallelizing the

for

loop. The function

Compute_Pi

shown on line [3] in Listing 8.4 computes the value of the constant π in a parallel way. This is done in accordance with the method outlined by Eq. (7.52), which computes the integral in Eq. (7.55).

In Listing 8.4, we can see two objects. The first, defined on line [5], is a constant

dx

. The second, on line [8], is a simple variable

sum

of type

double

. Both are shared, but only

sum

will be changed, since tithis is the total sum of all of the elements that are added in the loop. Therefore, it needs to be synchronized. But since this operation is very common, OpenMP has a special

reduction

clause that allows for easy, safe updates of the shared variable.

Let's now analyze line [11]. Its first part,

omp parallel for

, is an OpenMP directive that joins the action of creating a team of threads with concurrent execution of the loop (in OpenMP, only

for

can be parallelized this way). That is, dividing the data into chunks and distributing computations to threads, as illustrated in Figure 8.3, are entirely up to OpenMP. If the

#pragma

line is removed, we are left with a perfectly functional sequential version of the code. As mentioned previously, the shared variable

sum

is used to collect the sum of the series computed by all the threads. Therefore, after each thread finishes its job, the partial result needs to be added to

sum

. All of these actions are performed safely by providing the

reduction

( + : sum )

clause at the end of line [11].

The

for

loop on lines [12–18] is processed in parts by a team of threads. Note that the iterator

i

on line [12] is a local object and does not need to be treated in any special way. The same is true for

c_i

on line [14]. Also, the update of

sum

on line [17] does not require special protection since OpenMP knows its purpose as a result of the previous

reduction

clause and inserts a proper protection mechanism for us. Finally, the result is computed by the master thread on line [21], after the parallel section.

The only thing left is to launch

Compute_Pi

with various numbers N of elements in the series, as well as to measure the execution time. The

OpenMP

_Pi_Test

function, defined on line [23], performs these actions.

First, line [26] creates a list of N values to test. Then, on line [28], a sequential loop starts, which on line [32] launches

Compute_Pi

, each time with a different value of

N

. To measure the execution time, the OpenMP

omp_get_wtime

function is called two times to capture the start and finish timestamps.

The results, printed on lines [35–36], were as follows on our test system:

On the other hand, running the code with the

#pragma

commented out – that is, in a sequential fashion – gave the following output.

The computed values of π are identical for the same N. Naturally, this is good news. But even if we have coded correctly to avoid hazards with unprotected shared variables, there can be differences in numerical values. Why does this happen? Because operations on floating-point values are burdened by phenomena such as rounding errors. In effect, this means addition is not associative in general, as discussed in Section 7.4. Hence, the differences in the order of summation between the sequential and parallel implementations can result in slightly different values.

Interesting conclusions can also be drawn from collating the execution times for corresponding values of N, as shown in Table 8.2. Notice that in all the cases except the last, the sequential version of the code is faster than the parallel version. This may be surprising at first glance. But the explanation is apparent as soon as we recall that creating and calling threads consumes time and memory. Thus it is not efficient to launch threads for tasks with a small amount of data. This also explains why, for significant values of N, the parallel implementation is over six times faster. OpenMP has a special

if

clause that turns on the parallel mechanism only after a given condition is met. Hence, if line [11] is changed to the following

the previous code will execute as desired.

Table 8.2 Timings for sequential and parallel versions of the series summation algorithm with respect to the number N of summed elements.

N

|

100

|

1000

|

10 000 |

100 000 000

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serial [s] | 6e-07 | 4.6e-06 | 4.52e-05 | 0.51 |

| Parallel [s] | 0.027 | 7.9e-06 | 6–05 | 0.079 |

| Speed increase | 2.2e-5 | 0.58 | 0.75 | 6.5 |

8.4.3 Massive Data Parallelization

Our final example shows a parallel implementation of multiplying

EMatrix

objects. The

EMatrix

class was defined in Listing 4.7.

The definition of

operator *

begins on line [2] in Listing 8.5. The code follows the

MultMatrix

function presented in Listing 3.23; the only change is the addition of lines [15–18]. They contain the OpenMP directive with clauses to make the outermost

for

operate in a parallel fashion. We will explain their meaning and then test the performance of this function.

Actually, lines [15–18] are only visible as split into multiple lines: because of the line ending with the backslash symbol

\

, its following (but invisible) newline character is simply ignored by the preprocessor. In this context,

\

operates as a line continuation character, effectively reducing lines [15–18] to one line, which is necessary to be correctly interpreted as an OpenMP directive. We emphasize that to be a line continuation,

\

must be the last character in a line. We have already seen

\

in another context, i.e. in two-character escape sequences, such as

\n

,

\t

, and

\\

. Hence,

\

means two different things depending on the context.

The first

omp parallel for

on line [15], seen earlier in

Compute_Pi

, instructs OpenMP to prepare a team of threads that will run portions of

for

concurrently. The division of work is performed by the OpenMP library, but we will be able to give it some clues.

The second line

shared()

on line [16] declares all of the arguments to be shared objects. We know that these need to be treated in a special way to avoid hazards. However, since they are only read here, we do not need to include any synchronization objects like the

critical

, etc.

default( none )

on line [17] tells the compiler to list all of the objects used in the parallel section. Although all objects by default are treated as shared, their proper classification as shared or private is very important to avoid race conditions.

Finally, in line [18],

schedule( static )

defines the required work-assignment scheme for the threads. This line does not end with a slash, since it closes the entire

omp parallel for

directive. In the

static

scheme, each thread obtains roughly the same amount of work, which is optimal for a balanced workload. There are also other schemes, such as

dynamic

(OpenMP 2020).

The OpenMP directive with clauses pertains only to the first

for

loop on line [20]. The other two, i.e. on lines [21, 22], are local to each thread. Moreover, in each thread, these

for

loops operate sequentially, although nested threads are also possible in OpenMP.

Finally, note that all the other objects, such as

ar

,

bc

, and

ac

, are local: each thread will create its own copies of these objects. Therefore, they need not be protected from access by other threads. But as always, we need to be sure they are properly initialized.

If threads need to make a local copy of an object that is defined before

#pragma omp

, the object should be declared with the

private

clause. But this way, objects declared private are not initialized by default. To ensure proper initialization, we must either place the initialization (assignment) in the code or use the

firstprivate

clause.

The

OpenMP_MultMatrix_Test

function, defined on line [27], serves to prepare random matrix objects and run matrix multiplication to measure its performance time. Again, time measurement is accomplished with the

omp_get_time

function.

The results measured on our test machine are shown in Figure 8.4. Because only one line has the OpenMP directive (and with no other changes to the code), execution was six times faster.

Figure 8.4 Comparing the performance times for multiplying matrices of different sizes in a sequential implementation (blue) and a parallel implementation with OpenMP (red). For large matrices, speed increases by more than six times.

But again, we have only scratched the surface. There have been great achievements in the acceleration of computations. CPU/GPU hybrid systems are especially remarkable and led to the foundation of deep learning and AI. Returning to the problem of matrix multiplication,

EMatrix

is not an optimal representation. Also, more advanced multiplication algorithms are available to take advantage of cache memory (Section 2.1). For example, faster execution speed can be achieved by first transposing the second of the multiplied matrices and then using the multiplication algorithms with the second matrix transposed. As a result, if matrix elements are arranged by rows in memory, cache accesses are more optimal. Table 8.3 summarizes the most common OpenMP constructs, clauses, and functions.

Table 8.3 Common OpenMP constructs, clauses, and functions with examples.

| OpenMP directive | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

#pragma omp parallel for

[clause[[,] clause]… ]

|

Fork

for

loop iterations to parallel threads. |

In this example, a minimum value and its index are found in a vector.

omp parallel

starts a team of thread;

firstprivate

declares

loc_val

and

loc_offset

to be private for each thread and, at first, initialized exactly as in their definitions; and

shared

declares the objects to be co-used by all threads.

omp for nowait

says to execute the following

for

loop in parallel and not wait for other sub-loops, but to immediately proceed to

omp critical

. This is a guard for the critical section and can be entered by only one thread at a time.

|

| #pragma omp parallel | Starts independent units of work. | |

| #pragma omp single | Ensures that exactly a single thread executes a block of code. | |

| #pragma omp critical | Construction for mutual exclusion: at any instant only one thread can perform the block encompassed by

critical

. | |

| #pragma omp parallel sections | Creates a team of threads, and starts independent sections. Sections execute in parallel to each other. | |

| #pragma omp section | Starts independent units of work in a section. | |

private( list )

|

Declares a variable as private. Each thread contains its own uninitialized copy (for initialization, use

firstprivate

). | |

firstprivate( list )

|

Initializes a private variable with the value of the variable with the same name before entering the thread. | |

lastprivate( list )

|

Makes the last value of a private variable available after termination of a thread. | |

reduction( operator : list )

|

Orders parallel execution of the associative and commutative operations (such as

+

,

*

, etc.) with the aggregation of partial results at the thread barrier. |

|

ordered

|

Forces a sequential order of execution within a parallel loop. | |

schedule( kind [,chunk size])

|

Controls the distribution of loop iterations over the threads. The scheduling modes are static, dynamic, and guided. | |

shared(list)

|

Declares objects that will be shared among the threads. Each object can be freely accessed by each of the threads at any moment. Hence, objects that are written to have to be protected, e.g. with

omp critical

. | |

nowait

|

Threads don't wait for synchronization at the barrier at the end of the parallel loop construction. | |

default( none | shared )

|

Tells how the compiler should treat local variables. If

none

, then each variable needs to be explicitly declared as shared or private. If

shared

, then all variables are treated as shared. | |

num_threads( N )

|

Sets the number of threads to be used in a parallel block. |

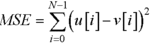

MSE

computes the mean squared error from the vectors

u

and

v

:  . .omp parallel for

is used to start parallel execution of a team of threads,

reduction( + : sum )

introduces a shared variable

sum

to be safely updated by the threads (so no synchronization is necessary),

schedule( static )

imposes an even burden on the threads, and

if

launches parallel execution only if N > 10 000.

|

| omp_get_num_threads() | An OpenMP function that returns the number of threads in the current team. | |

| omp_set_num_threads( N ) | Sets the number of threads to N. | |

| omp_get_thread_num() | Returns a thread number (its ID) within the parallel region. | |

| omp_get_nested() | Check whether nested parallelism is enabled. | |

| omp_set_nested( 0/1 ) | Enables or disables nested parallelism | |

| omp_get_wtime() | Returns an absolute wall clock time in seconds. |

In this example, a parallel pipeline is organized in sections. Threads in each section operate in parallel.

The omp_set_nested

function allows nested parallelism. The

num_threads

function sets a number of threads to be allocated for the closest parallel section. If a sufficient number of threads are available, then the

for

loop within

section

will execute the nested threads.

|

8.5 Summary

Questions and Exercises

- Refactor the matrix addition code shown in Listing 4.10 to allow for parallel operation. Hint: follow the code in Listing 8.5.

- As shown in Listing 8.5, matrix multiplication requires three loops. In theory, they can be organized in 3! = 6 permutations. Extend the code from Listing 8.5, and measure the performance of different loop structures.

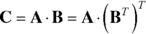

- Consider the following matrix identity

where BT means transposition of matrix B. What would be a computational benefit of implementing matrix multiplication in the following two steps?

- Matrix transposition B → BT

- Multiplication of a matrix with the transposed-matrix: ABT

Implement matrix multiplication in accordance with these two steps, and measure its performance. Compare with the code in Listing 8.5. Hint: analyze the operation of the microprocessor cache memory (Section 2.1).

- Implement a parallel version of the definite integration for any integrable function. Consult exercise 23 in Section 7.6. Measure its performance.

- Write test functions for the code snippets shown in Table 8.3, and measure their performance.

- Data variance provides a measure of how values from a data sample differ from their mean (data deviation measure). One of the methods to compute the variance is based on the following relations:

where

denotes the mean value of a vector x, and N stands for the number of elements in the vector.

- Implement a serial version of this two-pass algorithm.3

- Write a test function that will (i) create a vector with randomly generated values from a given distribution and (ii) compute their variance.

- Implement a parallel version of the two-pass algorithm. Compare the return values and execution times of the serial and parallel versions.

- Apply the compensated summation algorithms discussed in Section 7.4.7. Compare the results.

- C++20 comes with an interesting feature – coroutines. These are functions that can suspend execution and store the current state, to be resumed later with the state restored. This allows for a number of interesting mechanisms such as asynchronous tasks, non-blocking I/O handling, value generators, etc. A function becomes a coroutine if it contains any of the following constructions:

co_await,co_yield, orco_return. For example, the followingnext_int_gencoroutine returns the consecutive integer value on eachcall:

co_yieldsuspends execution of thenext_int_genfunction, stores the state ofvalobject in thegenerator< int >, and returns the current value ofvalthrough thegenerator< int >object.- Read more about coroutines (https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/language/coroutines), and write a test function to experiment with

next_int_gen. - Try to implement a new version of the

rangeclass from Section 6.5, using coroutines.

- Read more about coroutines (https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/language/coroutines), and write a test function to experiment with

- Implement a parallel version of the MSE defined in Table 8.3 using the

std::transform_reduce. Compare performance of your implementation with the OpenMP based version. - Using the

std::transform_reduceand thestd::filesystem::recursive_directory_iteratorimplement a serial code to recursively traverse a given directory and to sum up sizes of all regular files (see Section 6.2.7). Then design a parallel solution. However, since the above iterator cannot be directly used in a parallel version of thetransform_reduce, implement a producer-consumer scheme.