It is believed that the runes originally were derived from a northern Etruscan alphabet, which originated among peoples who dwelt in northern Italy and who spread into south central Europe. The earliest forms of runic writing developed among people who were living in Bohemia. At some point, the idea of using symbols as a means of communication traveled northward along the river routes to the lands in northern Europe and Scandinavia.

Pre-runic symbols have been found in various Bronze Age rock carvings, mainly in Sweden, and some of these are easily identifiable in later alphabets. Rune figures can be found chiseled into rocks throughout areas that were inhabited by Germanic tribes. These people shared a common religion and culture and their mythology was passed on through an oral tradition. The people of northern Europe used the rune script well into the Middle Ages. In addition to a written alphabet, runes also served as a system of symbols used for magic and divination, so in this way the process of writing became a magical act.

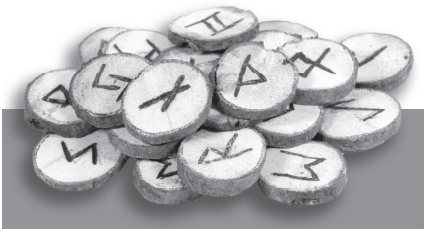

The arrival of Christianity in any particular Nordic area often resulted in a decrease or complete cessation of belief in local mythologies. However, it was the Vikings who colonized Iceland, so Christianity had a much weaker influence in that region. The pre-Christian myths were first written down in Iceland as a means of preserving them. When the Roman alphabets became the preferred script of most of Europe between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries, rune writing fell into disuse. Interest in the runes began to rise again in the seventeenth century, but the Christian church soon banned them. Runes have now been rediscovered as a symbolic system and have become very popular as an accurate means of divination. Their meanings derive partly from life in ancient times—for example, viewing cattle as a form of wealth—and partly from the stories of the Nordic gods and Norse mythology.

It is clear that the runes have always performed two functions: (1) that of containing, conveying, and imparting information through inscribed symbols—as a form of writing—and (2) for purposes of divination and magic.

Before the Germanic peoples of Western Europe possessed a true alphabet, pictorial symbols were carved into stones. About 3,500 stone monuments in Europe, mainly concentrated in Sweden and Norway, are claimed to have been inscribed with runic types of pictures, symbols, and signs. The earliest of these writings date from about 1300 BC, and it is likely they were linked to sun and fertility cults. The names given to the runes indicate that a certain power was ascribed to them. The most famous users of the runes were the Vikings, who inscribed them everywhere they went.

The name rune means “a secret thing or a mystery.” When the high chieftains and wise counselors of Anglo-Saxon England met, they called their secret deliberations “ruenes.” When Bishop Wulfila translated the Bible into fourth century Gothic, he rendered St. Mark's “the mystery of the kingdom of God” and used the word runa to mean mystery.

When the Greek historian Herodotus traveled around the Black Sea, he encountered descendants of Scythian tribesmen, who crawled under blankets, smoked themselves into a stupor, and then cast marked sticks in the air and “read” them when they fell. These sticks were used as a kind of runic form of divination. By AD 100, the runes were already becoming widely known on the European continent.

The most explicit surviving description of how the runes were used comes from the Roman historian, Tacitus. Writing in AD 98 about practices prevalent among the Germanic tribes, he reports:

To divination and casting of lots they pay attention beyond any other people. Their method of casting lots is a simple one: they cut a branch from a fruit-bearing tree and divide it into small pieces which they mark with certain distinctive signs (notae) and scatter at random onto a white cloth. Then, the priest of the community, if the lots are consulted publicly, or the father of the family, if it is done privately, after invoking the gods and with eyes raised to the heavens, picks up three pieces, one at a time, and interprets them according to the signs previously marked upon them. (Chapter 10, Germania)

Runes were used to foretell the future by casting, and they were also inscribed into tools, weapons, and many other items. Runic letters were also used by the clergy as an alternative to the Latin alphabet.

According to Norse belief, the runes were given to Odin, the father of creation, who was able to communicate with his people through the runes and gave them warnings, blessings, and even curses from their enemies.

The runic alphabet, known as the Futhark, appears to have been derived from two distinct sources. The first is considered to be Swedish, where pre-runic symbols have been found in various Bronze Age carvings, while a second case has been made for a Latin and Greek derivation of the runic alphabet. The roots of the runes are still argued among scholars. The strongest evidence appears to point toward a north Italic origin. There are close parallels between the forms of the letters used in that area, in addition to the variable direction of the writing. Both Latin and Italic scripts derive from the Etruscan alphabet, which explains why so many runes resemble Roman letters. This would place the creation of the Futhark sometime before the first century BC, when the Italic scripts were being absorbed and replaced by the Latin alphabet. Linguistic and phonetic analysis points to an even earlier inception date, perhaps as far back as 200 BC. As time went on, runes became standardized throughout Europe, in some places the runes numbering as few as sixteen, in other areas as many as thirty-six; however, twenty-four runes formed the basic alphabet or Futhark. The Anglo-Saxons are credited with spreading the runes throughout Europe.

The Common Germanic Futhark remained in use among most of the Teutonic peoples until approximately the fifth century AD. It was at about this time that the first changes in the Futhark emerged on Frisian soil. The fifth and sixth centuries were a time of great change for the Frisian language, during which many vowels shifted in their sounds while new phonemes were added. This necessitated the expansion of the rune row, and in this first expansion four new runestaves were added to represent the new sounds in the Frisian language. The changes in the Frisian language also represented many of the changes that would be seen in Old English. Starting in the eighth century, more runestaves were added. It must be pointed out, though, that some of these staves are not proper runes, but rather pseudo-runes.

In the eighth century, the Old Norse language went through changes. Sounds shifted, some ceased to be used, and others were added. Old Norse speakers reduced the size of the rune row from twenty-four to sixteen. As some sounds stopped being used, the runes that represented them accordingly fell out of use. Similarly, the sounds of some runes were taken over by other runes, which resulted in the disappearance of those runes as well.

Though we speak of the Younger Futhark as if there is only one, in reality there were two different Norse Futharks: the Danish and the Norwegian-Swedish, As might be expected of a script that often uses a single stave to represent several different sounds, the sixteen-rune row Futhark apparently proved practical for writing. Eventually, a system of “pointed runes” developed, whereby a runestave that denoted several sounds would have a point or dot added to it in a particular place to differentiate between sounds. This appears to have started in Denmark and spread outward. Unlike the Anglo-Frisian rune row, the Younger Futhark did not fall completely out of use, so the runes were being used well into the Middle Ages—so much so that Iceland eventually banned their use.

From the ninth through to the twelfth centuries, the runes were carried to Anglo-Saxon England and to Iceland. Rune carvings have been found as far afield as Russia, Constantinople, the Orkney Islands, Greenland, and—some believe—North America.

Shaped by the tribal wisdom of northern Europe, the Viking runes soon emerged. With the onset of Christianity, the runes were associated with demonic forces. By AD 800 rune use began slowly to wane on account of persecution of their users.

The situation was different in England; runes were not actively suppressed by the Church. They fell out of use—even for inscription purposes—by the ninth century, at which time they were overtaken by the Latin script. However, they were still being used (albeit in a more limited fashion) in Scandinavia and Iceland.

In 1486, the book Malleus Maleficarum by Henricus Institoris (Heinrich Institoris Kraemer) and Jacobus Sprengerus (Johann Sprenger) set off the witch hunt that was to spread throughout all of Europe. This book was more or less a guide to witch hunting and specifically mentioned runes:

Or even let us conceive that if they superstitiously employ natural things, as, for example, by writing down certain characters or unknown names of some kind, and that then they use these runes for restoring a person to health, or for inducing friendship, or with some useful end, and not at all for doing any damage or harm, in such cases, it may be granted, I say, that there is no express invocation of demons; nevertheless, it cannot be that these spells are employed without a tacit invocation, wherefore all such charms must be judged to be wholly unlawful.

Nevertheless, the runes did not disappear. The Elizabethan magician John Dee worked with runes, and mystical works about rune interpretation and magic continued to be written.

Calendars known as primstave, or runstaf, were used to mark Church holy days as well as planting and harvesting times, and persisted beyond the medieval period in Scandinavia. An indication of their enduring popularity is evident from a seventeenth-century inscription on a church choir wall in Oland, Sweden, which reads, “The pastor of the parish should know how to read runes and write them.” Among the country people of Dalarna, a remote region of western Sweden, knowledge of the runes continued into the twentieth century. In Norway, among the Lapps of Finnmark in the country's far north, drums that have runes painted on them are still in use today by local shamans.

Until the seventeenth century, runes were in such common use that they were found on everything from coins to coffins. In some places their use was actually sanctioned by the Church. Even the common people knew simple runic spells, and runes were frequently consulted on matters of both public and private interest. However, in 1639, they were banned by the Church, along with many magical arts, in an effort to “drive the devil out of Europe.” By this time, runes were of interest primarily to antiquarians, but during the Enlightenment, interest in the runes was rekindled. Scholars transcribed the runic poems and made the first studies into the runes and runic inscriptions. By the nineteenth century, many scholars were studying the runes.

In 1902, the Austrian journalist and author Guido Von List suffered a period of blindness following a cataract operation. It was during this period that he experienced a vision in which an alternative set of runes was revealed to him. He published the details of his experience in his book The Secrets of the Runes, in 1908. Von List was a German nationalist and his runes were linked with the mythological and racial ideology that was Armanism. He founded the Thule Society, which was an occult and right-wing political organization, in order to propagate his views.

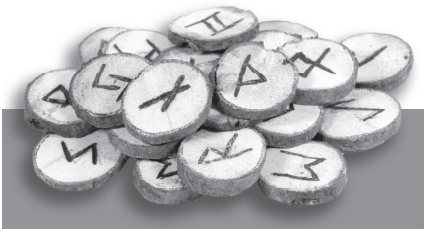

A tracing of The Möjbro

A tracing of The Möjbro

Runestone, ca. 5th century,

Uppland, Sweden. The inscription

is in reverse, and meant to be read

from right to left.

In more recent history, the runes were revived by German researchers connected with the Nazi movement in the 1920s and 1930s. Although occultism was officially banned under the Nazis and many leading German occultists were imprisoned, key members of the party, such as Heinrich Himmler and Alfred Rosenberg, the official idealogue of the Nazi party, had a strong interest in the occult. Hitler was less interested, but he knew the value of symbols and incorporated Roman, Scandinavian, and ancient Germanic symbols of power into flags, staves, emblems, and uniform badges. The works of Von List therefore found favor, and his Armanen runes were adopted by the party for number of their badges and emblems. The Tiwaz ( ) rune served as the badge of the Hitler Youth movement. The rune Sowelo (

) rune served as the badge of the Hitler Youth movement. The rune Sowelo ( ) (or sigil as it was known to the Nazis) was linked with the German word sieg (victory), and a doubled version of Sowelo became the logo of the SS. The lightning flash emblem of the British Union of Fascists was also inspired by this rune. During Nazi rule, runes were used throughout Germany—even on tombstones.

) (or sigil as it was known to the Nazis) was linked with the German word sieg (victory), and a doubled version of Sowelo became the logo of the SS. The lightning flash emblem of the British Union of Fascists was also inspired by this rune. During Nazi rule, runes were used throughout Germany—even on tombstones.

After the Second World War, most likely due to their association with Nazism, runes fell into disfavor, and very little was written about them until the 1950s and 1960s. Interest revived slowly as organizations such as the Odinic Rite and the Ring of Troth were formed to further the study of the northern mysteries and to pursue the religion known as Asatru.

It was not until the middle of the 1980s, with the widespread appeal of the “New Age” movement and the revival of pagan religions (especially the Asatru movement), that the runes regained their popularity as both a divinatory system and a tool for self-awareness. However, as early as 1937 runes gained ground in the United Kingdom with the publication of J. R. R. Tolkien's The Hobbit. Runes were used in the map and cover illustrations of the book. Tolkien continued to use runes as “dwarfish” writing in his other books. Runes appear on the title pages of The Lord of the Rings, which was published in 1954. Tolkien is said to have taken his runes from a Viking longboat discovered in the river Thames. In the 1970s, heavy metal bands such as Led Zeppelin used runes as illustrations on album covers, and accusations of Satanism led to runes being associated with black magic during this period.

By the mid 1980s, a large number of rune books were being published. Ralph Blum's book, The Book of Runes, which was accompanied by a complimentary set of runes, started the trend, and it has continued to be the best seller in the genre. Blum drew very little upon the original lore. He even created his own order for the rune row rather than relying upon the traditional Futhark. Blum also introduced the blank rune, although he does not claim responsibility for inventing it. He claims it was included in a set of runes he purchased in Surrey. Many regard it as a misinterpretation of the runes, leading to an upset in their balance. Runes are now popular as a divinatory system, and many people in recent years have been attempting to reclaim their long history.

All systems of divination stem from mythology, religions, philosophies, and beliefs. It is the instinctive fear of these so-called pagan ideas that leads those who sincerely believe in one of our modern religions to vilify these systems. Among those who learn the various divinations, some are fascinated by the stories that underpin them, while others view them as an irrelevance that gets in the way of their desire to use the particular system. However, without knowing what signs, symbols, and archetypes divinatory systems are derived from, how can anyone hope to understand their true meaning? The runes are so heavily dependent upon an ancient belief system, complete with a full cast of characters and a variety of occult meanings, that it is essential to have at least some understanding of the origins of their images.

Hundreds of years before the Christian era, the Germanic people settled over much of Central Europe, living in what is now modern Scandinavia and Germany. Though covering a wide area, they shared a culture, and their myths were passed on through oral tradition. With the advent of Christianity, the northern and Teutonic mythologies faced an end to their development. However, when the Vikings colonized Iceland (which was less influenced by Christianity), their ancestral religion became preserved; thus, it is in Iceland where the myths were first recorded in writing. The tenth-century compilation Eddas offers thorough descriptions of cosmogony, mythology, and the traditions of the Teutonic and Nordic tribes. These early peoples were called Asatru, an Icelandic word meaning “those of the Aesir.” Although replaced by Christianity, their religion was kept alive in Iceland and Lapland into the nineteenth century, and was revived in the 1970s. The Asatru worship the deities of the ancient Norse and Germanic peoples.

The Asatru believed in the “Nine Noble Virtues” of courage, honor, loyalty, hospitality, industriousness, truth, perseverance, self-discipline, and self-reliance. They revered their ancestors and their “honored dead”—those who were killed in battle—and they also revered nature and the spirits of the world. They held hospitality and truth as their highest ideals. The Asatru held four major holy celebrations, which occurred in autumn, at the beginning of winter, in midwinter, and at the beginning of spring.

The gods of Asatru were not seen as remote creatures but rather as beings who exerted an influence on the world and who were considered to be prone to the same flaws as humans. They were subject to the universal laws and could not escape Wyrd, the cosmic justice that forced them to face the consequences of their deeds. Death would come to them all at the end, particularly at Ragnarok—the Twilight of the Gods.

We do not have to go very far into history for spelling to be a moveable feast. For instance, in British English the following words are all spelled differently: behaviour, travelling, centre, symbolise, and criticise. The spelling associated with the runes and their history stretches across many centuries and languages, so there are many variations in the way these mythical characters and places are written within each type of Futhark. In this book, I have made my own choices and kept them reasonably consistent, although there are some extremely obvious slight variations. For instance, Muspell is sometimes referred to as Muspellheim—heim being “home or place of.” Interestingly, heim still means “home or area” in modern German. In addition, there is no distinction between common and proper nouns in German, so all nouns are written with a capital letter, as are the words Futhark and Aettir in this book.

At the beginning of time there was Muspell, which was the realm of Fire. Only the Fire Giants could tolerate the light and heat of Muspell. It was guarded by Sutr, who was armed with a flaming sword. It was believed that at the end of the world he and his companions would destroy the gods and that the world would be consumed by fire. Outside Muspell was an empty land called Ginnungap. To the north was a land of dark and cold called Nifelheim with eleven rivers that flowed from a great well, which froze and occupied Ginnungap. When the wind, ice, and cold met the heat of Muspell in the center of Ginnungap, a place of light, air, and warmth was born and thawing drops of ice appeared. The Frost Giant, Ymir, slept beneath the melting ice. Under his left arm grew a pair of male and female giants. One of the male's legs begot a son with the female. The melting frost became a cow, Audhumla, from whose udders ran four rivers of milk that fed Ymir. After a day spent licking ice, she freed a man's hair. After two days, she freed his head. And on the third day, she freed him completely. This man was called Bury. Bury married Bestla, the daughter of a giant, and they had three sons called Odin, Vili, and Ve'.

The three brothers killed Ymir and carried him to the middle of Ginnungap, creating the world Midgard from his body. Ymir's blood became the sea and lakes, and his skull became the cover of the sky. His brains became the clouds; his skeleton became the mountains; his teeth and jaw became rocks and pebbles; and his hair became the trees. The maggots from his flesh became dwarves, who looked like humans and had human understanding, and lived in the earth. The sparks and burning embers from Muspell gave light, and the stars were named and set in their paths.

Midgard was surrounded by an ocean. Odin, Vili, and Ve' gave lands to the friendly giants who were called the Etin. The Etin created a man and woman from two trees. Odin filled them with spirit and life, while Vili gave them understanding and movement, and Ve' gave them clothing and names. The man was named Ask (Ash) and the woman Embla (Elm), and they are the ancestors of all humans. The brothers then built Asgard, the home of the gods. Odin married Frigga, the daughter of the giant Fjirgvin.

The World Tree, Yggdrasil, rose from the center of Asgard, with its branches reaching over Asgard. One of its roots reaches into the underworld Hel (also called Hell or Helheim). Another root led to the world of the Frost Giants, and a third root led to the world of humans. Underneath the world tree is the Urda well, which was guarded by the Norns, the goddesses of fate who used the well to irrigate the roots of Yggdrasil.

The Norns were three sisters, goddesses of fate, who had some link with the older, pastoral gods called the Vanir. They represented time, so Urd, the Norn of the past, was depicted as an ancient crone who constantly looked back to the good old days. The young and lively Verdandi, Norn of the present, looked alert, while Skuld, the Norn of the future, was mistily pictured in a veil holding an unopened scroll. The Norns were occasionally led by an elemental force called Wyrd, who some scribes recorded as a person representing their mother. The Norns wove the Web of Wyrd (fate), which sets out the fate of gods and humans. This web was so huge that it covered the known world—it is interesting to note that the word weird, with its strange e-before-i spelling, still lingers in our consciousness today.

The wells of Hvregelmer and Mimir also fed Yggdrasil. The dragon Nidhog laid in Hvregelmer's well and gnawed on the roots of the tree. Mimir's well was the well of wisdom and was guarded by Mimir. Odin gave his right eye for a drink of the water from Mimir's well.

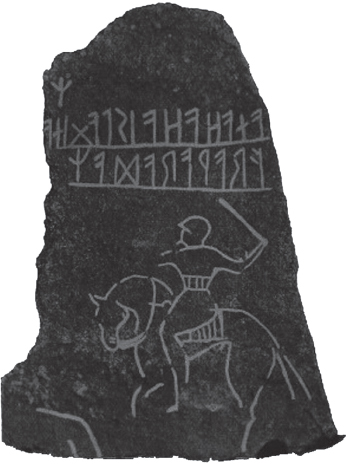

Mimir originally possessed the knowledge of the runes, which he obtained from the underground fountain that lay beneath the middle root of the World Tree that he guarded. After being pierced by a spear, Odin hung upside down from World Tree with no food or drink for nine days and nights. On the ninth night, he saw the shapes of the runes in the trees' roots. Crying out, he caught up the runes from the World Tree. Besla's brother gave him a drink from the fountain. He received nine of the songs that were the basis of the magic that lies in the application of the power of words and of the runes over spiritual and natural forces. The runes then became a channel for the protection of the gods, which enabled them to assist their worshippers when in danger or distress.

The runes of Victory could stop weapons and make those who Odin loved protected against the sword. Other runes had powers that controlled the elements, gave speech to the mute, freed the limbs from bonds, protected against witchcraft, took strength from the love potion prepared by another man's wife, helped in childbirth, healed the sick, gave wisdom and knowledge, and extinguished enmity. Odin taught the knowledge of the runes to his own clan; Dinn taught the elves; Dvalinn taught the dwarves; Asvinr taught the giants; and Heimdal taught the runes to humanity, in particular to selected noble families who were said to possess the power of the runes as a gift of the gods.

Odin sacrifices himself by hanging from the World Tree, Yggdrasil. Illustration for “Hávamál,” in Den ældre Eddas Gudesange, 1895 edition.

The gods built a bridge from a rainbow between Asgard and Midgard and rode across it daily. It was guarded by the god Heimdal, who supposedly slept lighter than a bird, could see one hundred travel-days in each direction, and could hear grass and wool grow. It is said that the bridge will collapse when the Frost Giants ride over it at Ragnarok.

The gods were divided into two groups: the Aesirs and the Vanir. The Vanir, or earth gods, symbolize riches, fertility, and fecundity, as they were associated with the earth and the sea. The most important gods of the Vanir were Njord, Freyr, Aegir, and Freya. The Aesir, or sky gods, symbolized power, wisdom, and war, and were not immortal. The Aesir lived in Asgard in two buildings, Gladsheim for the gods and Vingolf for the goddesses. The Vanir were the older race of gods and were also masters of magic. They lived in Vanaheim.

There was a clash between the two sets of gods, making the Aesirs, led by Odin and Frigga, and the Vanir, led by Heimdal, Freyr, and Freya, into enemies. The spark that ignited this war was an attempted murder by the Aesirs of the oracle and sorcerer Gullveig, who was said to be concerned only with her love for gold. The Aesirs burnt Gullveig to ashes three times, but each time she recovered. The Vanir, angered at her treatment by the Aesirs, prepared for war.

Eventually, peace was declared, and the gods exchanged hostages. The Vanir sent Njord and his children, Freya and Freyr, to Asgard, while the Aesirs sent Honir and Mimir to Vanaheim. Honir caused the Vanir to be suspicious. Believing they had been cheated, they beheaded Honir and sent his head back to the Aesirs. The dispute was eventually resolved. The Vanir became assimilated, and all the gods continued to live in Asgard.

Odin was the leader of the gods. Thor was the god of thunder, and Loki was a giant who became an Aesir by adoption, thus a blood brother of Odin. Loki was a trickster. Odin's son, Baldur, settled disputes. Baldur had a dream in which his life was threatened. His mother, Frigga, forced the elements of fire, water, metal, and earth—as well as stones, birds, and animals—to swear not to harm him. Loki discovered that the only thing that could harm Baldur was mistletoe—so he created a set of arrows with it. He took the arrows to the blind god Hodor, who was Baldur's brother, and had Baldur killed. Baldur did not die in battle, so he was sent to Hel. Odin begged for Baldur's release. Hel, who was Loki's daughter, decided to release Baldur only if everything in the world, alive or dead, wept. The only one not to respond to Hel's plea was the giantess Thokk, who was actually Loki in disguise. The Aesir captured Loki and chained him beneath a serpent that dripped venom upon him as punishment for his crimes, causing him great pain.

When Mimir ceases to guard his well, Yggdrasil's root will start to rot, and the Nidhog dragon/serpent will gnaw through the root at Hvregelmer's well. Odin's sacrificed eye will see the coming of three years of an endless winter followed by Ragnarok. One of Yggdrasil's branches will break and fall, striking Jormungand (the world serpent), which immediately will let go of its tail. [Note: Some traditions suggest that Jormungand is a turtle and that the tree and the world are all perched on its back. The popular fantasy books by Terry Pratchett use this myth as their basis.]

The Het ship, Naglfar, will become visible in the mist. The wolves Skoll and Manegarm will move closer and closer to Sun and Moon. Loki will be released by giants, and Nidhog will leave the roots of Yggdrasil and head toward Asgard. As the giants march on Asgard, Heimdal will sound a warning and Loki will lead the monsters and giants in their last great battle. Many of the gods will die and the World Tree will fall down and burn. Some Aesir will escape in Frey's ship. Midgard will be destroyed by fire and sink back into the sea. Finally, the earth will re-emerge from the sea, and seven son's of the dead Aesir will return to Asgard and rule the universe.

Before continuing, we need to fully understand the nine worlds that comprise the universe and which are all connected by the roots and branches of the World Tree, Yggdrasil, and which are subject to the web of Wyrd. Odin traveled freely through these worlds on the back of his mighty eight-legged stallion Sleipnir. Ancient sorcerers also traveled on dream journeys through these worlds using the runes as talismans, amulets, and keys to other realms of existence. Keep in mind the following: