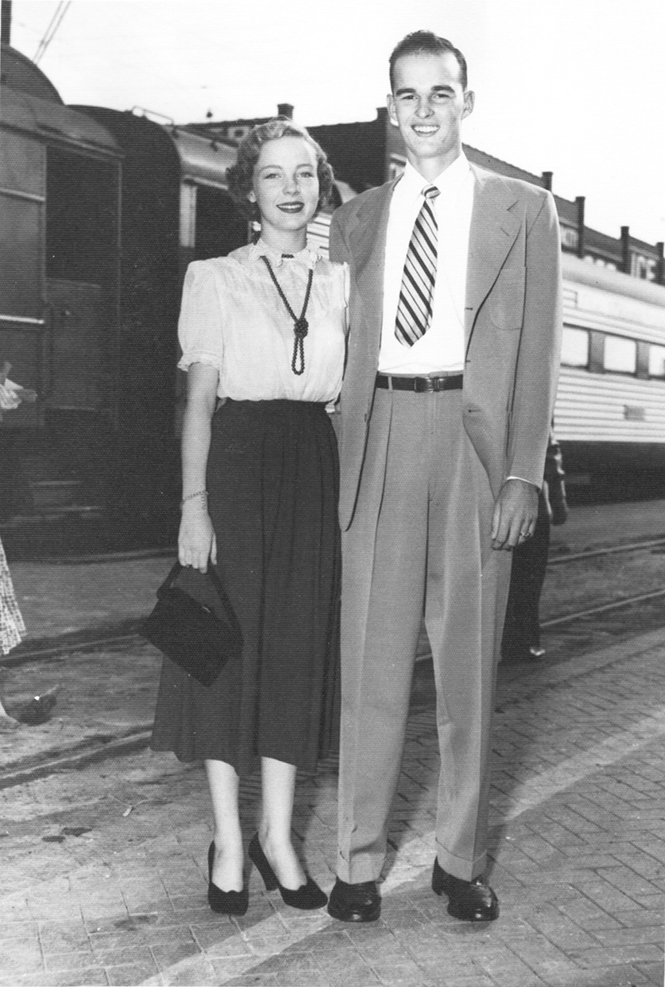

Mom and Dad, age sixteen, as Dad gets shipped off from Waco, Texas, to Andover.

In a way, I’d been preparing for the showdown on Capitol Hill my whole life. I was raised by troublemakers. Neither of my parents ever backed away from a righteous fight.

My father, David Richards, is a civil rights attorney whose career has been rabble-rousing. And Mom? From her earliest days rebelling against the social norms of Waco to becoming the first woman elected in her own right as governor of Texas, she believed she was on this earth to make a difference. It has been nearly thirty years since she gave her famous keynote address at the 1988 Democratic National Convention in Atlanta, yet people still quote me a line or two as if it were yesterday.

My folks grew up in the hard-core Baptist environment of Waco, Texas, high school sweethearts from different sides of town. Mom’s parents were Depression-era survivors, country folk from humble beginnings who worked long and hard for everything they had. Her father—Cecil, for whom I’m named—worked for a wholesale druggist and traveled to small-town drugstores throughout central and western Texas selling his wares. Poppy, as I called him, was well over six feet tall, with a gentle way about him. He never graduated from high school, yet his street smarts and keen sense of people made him a natural salesman. He always had some hilarious way of stating the obvious. “That’s no hill for a stepper” was a favorite. In other words, “You can overcome anything if you’re determined.”

Mom’s mother also had little in the way of formal schooling. But she knew how to fend for herself and her family; she made my mother’s clothes and grew and canned all her own vegetables. There was never a moment when the deep freezer in the garage didn’t have enough food to survive a nuclear holocaust. But not canned tomatoes. Poppy swore he had eaten so many canned tomatoes during the Depression he couldn’t bear the sight of them.

Nona, as we called her, was no-nonsense and did not suffer fools. The day my mother was born, going to the hospital was unthinkable; they didn’t have the money, and giving birth at home was just the country way. When Nona went into labor she called a neighbor woman to come over and cook for Cecil, as it was unimaginable that he would make his own dinner that night. The story goes that the neighbor was struggling to kill the chicken that was planned for his meal, so my grandmother hoisted herself up on one elbow, reached out her other hand, and wrung that chicken’s neck right there from the birthing bed. Mom told that story every chance she got. “Mama is tough,” she’d say with a mix of pride and awe. “She isn’t scared of anything.”

Dad’s parents were on the other end of the social spectrum from Mom’s. They were Waco society and belonged to the Ridgewood Country Club. They traveled the globe when that was unheard-of in Texas, and it was my grandmother Eleanor who later introduced me to the world. Worried that their only son would fall in love at such a young age with a Waco girl, they shipped my father off to Andover, a prep school in Massachusetts, in hopes of breaking up the romance. My dad rebelled and soon was back at Waco High and back with my mom.

My parents were a “power couple” from the get-go. Mom was the star of the school debate team, and Dad’s mother had raised him to hold his own beliefs—which from a young age were progressive by any standards, let alone in 1950s Waco. His favorite book as a child was The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood—he loved Little John—and it seemed to inform his politics later in life. On weekends the two of them would see a movie and split a milkshake, then stay out as late as they could, getting into impassioned political arguments. As Dad said later, they were in a rush to grow up and get about the business of life.

Mom and Dad stuck around Waco after high school. They enrolled at Baylor University, a Baptist school where, in Mom’s words, everything was more fun because it was either against the rules or a sin. The singer Marcia Ball jokes that no one at Baylor had sex standing up because someone might think you were trying to dance. It wasn’t until the late ’90s that the school finally broke down and decided to lift the infamous dancing ban; up to that point, it was basically the provincial town from Footloose. For much of my life, Waco’s biggest claim to fame was being the home of Dr Pepper and near Abbott, the birthplace of Willie Nelson. Now when people think of Waco, they’re more likely to mention the HGTV show Fixer Upper.

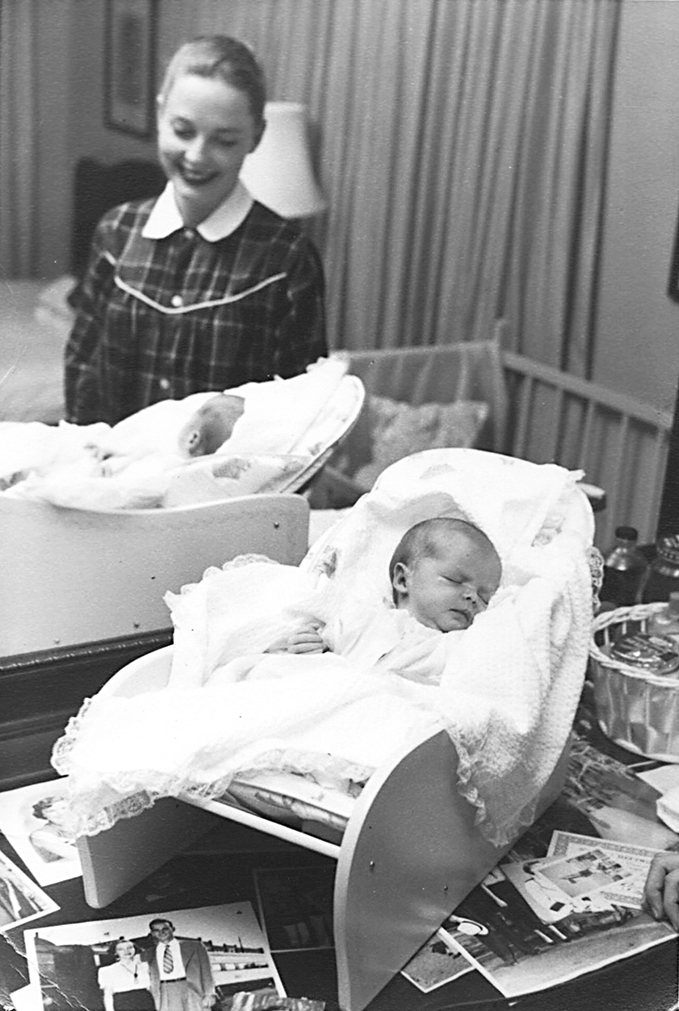

My parents married in 1953 after their junior year of college. A year later they moved to Austin, where Dad went to law school and Mom took graduate classes for her teaching certificate and taught junior high. She later said it was the hardest job she’d ever had, and the experience solidified her lifelong respect for public school teachers. Once he graduated, Dad took a job with a Dallas law firm known for representing labor unions and taking up civil rights cases—two things few others were doing at the time. Right about then Mom realized she was pregnant with me. She was eager to take on the big city with my father, but Nona was determined that her first grandchild would be born in Waco, where she could be close at hand. So Mom grudgingly moved back home until I was born.

It was 1957. The Supreme Court had recently declared segregated schools unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education, and the Little Rock Nine enrolled at Central High in Arkansas. It was an exciting time for America and for Dad, but there was Mom: pregnant, living with her parents, and going stir-crazy. Years later she lamented, “David was starting a new career and I was in my old room.” As soon as I was born, she hotfooted it out of Waco to join Dad in Dallas and never looked back.

After me came my brothers, Dan and Clark, and later my sister, Ellen. We spent our early years in Dallas, in a house on Lover’s Lane. It was small and cramped for the six of us, but Mom spent long hours decorating to try to make it look like the Dallas homes she’d seen in photos; after all, we weren’t in Waco anymore. Wallpaper was in fashion, so she put it up in every room: paisley in the tiny kitchen, white with flowers in the upstairs bedroom. She refinished an old set of dining-room furniture; nothing we had was ever really new, but by the time she was done it looked like it was.

Mom and me in her childhood bedroom.

In those days women in our neighborhood were expected to stay home, take care of the family, and help make their husbands successful. Mom pursued her role as a housewife with purpose. While Dad was working on “a big, important case,” she baked our birthday cakes from scratch and tried every latest recipe from Good Housekeeping. On special days she made chocolate meringue pie; I can still see it sitting on the counter, with beads of sugar forming on top. She drove us to swimming class and took Ellen and me to Brownies and Girl Scouts, made our Halloween costumes, and sewed some of her own clothes. Holidays were epic. We spent days preparing for Easter. Never one to do anything halfway, she’d have us dye dozens of eggs, wrap hundreds of jelly beans in plastic wrap, and throw the biggest Easter egg hunt around. At Christmas she put up the tallest, most elaborately decorated tree. It became an annual tradition: she’d let us all help hang the ornaments, then, true to form, stay up all night disassembling and reassembling to make sure it looked absolutely perfect, tinsel and all. As she once said, “If it was in a glossy magazine, I was doing it!” It was as if every effort was a campaign, soup to nuts. Why go small?

But even early on, I could see that Mom was quietly beginning to revolt against the role she was expected to play. One event in particular is seared into my brain. My father and some friends had planned to take a canoe trip for a few days, and he asked Mom to pack up everything they would need, including their meals. On the day before they left, while Dad was at work, Mom and a friend got together for the afternoon and plotted. They laid out plastic bags and marked each with the day and meal: “Saturday breakfast,” “Sunday lunch,” and so on. Then they filled them with the absolute worst things they could find. From canned diet drinks for losing weight to stewed prunes, each meal was more unappetizing than the last. Everything was so neatly packaged and labeled—as was Mom’s way—that Dad had no idea what was in store until he and his friends got on the river. I don’t believe he left her at home with four kids for a canoeing weekend ever again.

People often say to me, “It must have been incredible to have Ann Richards as a mom!” And of course it was. But to paint the picture a bit more clearly, it was not as if this young mother, the only child of working-class parents, sprung fully formed as a feminist icon. That happened over the course of many years. I suspect it was those early days in Dallas, being the perfect wife and mother, that set the stage for her rebellion later on.

Life in Dallas back then is hard to imagine unless you experienced it. The city was segregated and rampant with racism and homophobia. Dad had been working along with others to fight the poll tax, a scheme to prevent African Americans from voting that was finally declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1966, when I was nine. I recall police raids on movie theaters where gay men were known to congregate, though I was barely conscious of it at the time. Years later my son and I went to see the film Milk, which starts with black-and-white footage of raids on gay bars in the ’60s and ’70s. He turned to me and asked, “Mom, what are the police doing?” I realized then just how different my upbringing in Dallas had been from his world.

Mom shared Dad’s passion for progressive causes, but while he fought injustice in the courts, she was bound to us kids and had to find her own ways to resist the status quo. I remember her dragging my brother Dan and me to the local A&P grocery one day. She marched in and made a beeline for the produce aisle, a woman on a mission. As if we didn’t already have a reputation for being troublemakers in the conservative, wealthy, University Park neighborhood in Dallas, she walked right up to the young teenager stocking the shelves, a head of lettuce in her hand, and asked, “Where is Mr. Jones?”

Mr. Jones was the manager, and he was unaccustomed to political activities at his store. He approached Mom with a cheerful smile on his face and asked, “How can I help you, Mrs. Richards?”

Mom skipped the pleasantries. “You know there is a lettuce boycott on. Where did this head of lettuce come from?”

“Well, I can’t say for sure,” he admitted.

“Well, I want to see the crate it came in, because if it doesn’t have a United Farmworkers label, I’m not buying,” she said.

Mr. Jones, knowing full well the crate didn’t have a United Farmworkers label, hemmed and hawed until Mom finally cut him off. She made it clear her family wasn’t eating any more iceberg lettuce or any grapes until they had a union label. We didn’t have either in the house after that, and I don’t eat iceberg lettuce or grapes to this day.

Her keen interest in social issues and politics ended up being what kept Mom sane in those years. With a tree house in the backyard, a basketball hoop in the driveway, and a station wagon parked in the garage, we looked like the quintessential upper-middle-class Dallas family. But while other families bowled, we did politics. Many of Mom and Dad’s friends were running for office, mainly trying to beat the Dixiecrats who ran the Democratic Party across the state, and we went all in. At one point my dad ran for precinct chair and toppled an establishment candidate.

While we were growing up, our dinner table was never for eating—it was for sorting precinct lists. The earliest photo I have of me walking is at age two, out on our front lawn with a yard sign advertising the congressional campaign of Barefoot Sanders, a progressive Democrat. Our after-school activities were as likely to include stuffing envelopes at campaign headquarters as they were going to gymnastics or soccer practice.

As time passed and my parents’ involvement in local politics expanded, our house on Lover’s Lane became the local gathering place for misfits and rabble-rousers, with parties until the wee hours. My parents hosted local progressive politicians, activists, photographers, and writers from the Texas Observer and the New York Times. Shel Hershorn, the photojournalist who shot iconic photographs of the civil rights movement as well as the picture of Lee Harvey Oswald mortally wounded by Jack Ruby, lived down the street. He and his wife, Connie, were regulars, along with Sam and Virginia Whitten, my parents’ best friends. They’d come around to drink and smoke and commiserate about the city’s sorry state of affairs, and sometimes play a raucous game of “dirty charades.” It was one long continuum of liberal camaraderie, and Mom was the life of the party. It was much later that I realized those early days may have foreshadowed my mother’s struggle with alcohol. All of their friends drank, so it never seemed out of the ordinary. Didn’t everybody’s parents have a few martinis before dinner?

Of course we kids were sleeping during most of those late nights. More than once, my siblings and I would wake up for school in the morning to find some stranger snoring on the couch—the latest traveling reporter or union leader from out of town. Having grown up in that exciting environment, to me, politics never seemed like a chore; it was where the action was.

• • •

Like other progressive Democrats in the 1960s, my parents were in love with the Kennedys. Mom followed everything they did and pledged never to wear white shoes because Jackie Kennedy never would. We even lived in Washington for a couple of years early in the administration, while Dad worked for the Civil Rights Division in the Department of Justice. He was thrilled to be there when the civil rights movement was taking off. Later he told me that change suddenly seemed possible and that Washington had been part of the “new frontier.” But the days of that new frontier were coming to an end.

For Mom, finally getting out of Texas was energizing. She loved Washington. We lived on Capitol Hill, traveled to Mount Vernon, and went to the White House Easter Egg Roll. Mom took us to the National Gallery to see Renoir’s Girl with a Watering Can, a painting she had only ever seen in picture books. She even wrote to Jackie Kennedy to explain that little Caroline and I were the same age, and she thought it would be neat if we could play together. That didn’t happen, but for her, the sky was the limit.

Washington was a refreshing respite for all of us, but after two years Dad grew frustrated with the glacial pace of government bureaucracy. He was surrounded by passionate, well-intentioned people, but for all their high hopes, nothing ever seemed to happen. He told Mom it was time to return to Dallas, where he would go back to practicing law, and that was it.

Things were bad back in Dallas—worse than before we’d left. As Dad described it, “Right-wing hysteria seemed to be everywhere.” One billboard at the time declared, “Get the U.S. Out of the U.N.,” which pretty much summed up the mentality of the city. None of that stopped Mom from throwing herself back into the local political scene—if anything, it spurred her on.

On Friday, November 22, 1963, President John Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon Johnson came to town, greeted by a full-page ad in the local paper accusing them of treason. Mom was at the Adolphus Hotel, along with other Democratic women, waiting to welcome the president and vice president to the lunch they were scheduled to attend. My dad left his downtown office to stand on the street and wave to the motorcade, which passed by right before turning onto Dealey Plaza. Years later Dad talked about that day and how close he was to the president, sitting there in an open car. Dad said he could practically have reached out and touched him.

I was sitting in my first grade classroom that day when a teacher came running in to announce that President Kennedy had been assassinated. The way Mom used to tell it, the kids in the Dallas schools applauded when they heard the news. That may have been true for older kids, but my classmates and I were just six or seven, so I’m not sure any of us really understood what was going on.

They dismissed school early, and by the time I got home, I knew something big was happening. My parents and their friends were glued to the TV, clearly shaken. The death of the president, and within a few days the murder of Oswald on live TV, sent them into despair. They did the only thing they could think to do, which was pack up the family and go camping for the weekend with friends. They were terrified of what Dallas had become and were increasingly convinced that we had to move.

A few years later we decamped to Austin. If Dallas was the heart of right-wing conservatism, Austin was the motherland of the resistance.

• • •

To a twelve-year-old, Austin felt like nirvana. Unlike Dallas, where we never fit in, Austin was full of hippies and protests and love-ins. My brother Dan grew his hair long; we tie-dyed our T-shirts and started a garden in the backyard. Mom ordered hundreds of ladybugs so we could grow vegetables without pesticides, and we planted tomatoes, asparagus, and more. The Vietnam War was raging, and Dad was representing conscientious objectors, defending them from being sent to war against their religious or moral objections. We held benefits at our house for antiwar activists. Mom threw herself into all the things she could never have done in Dallas and seemed to be having a blast.

As was true of so many progressive cities during that era, Austin culture and activism were fused together. It was the 1960s, the decade of hippie counterculture and radical social change; the year of Woodstock, the iconic music festival that brought half a million concertgoers to upstate New York for three straight days of “peace, love, and rock ’n’ roll.” Early Austin bands like Shiva’s Headband and Freda and the Firedogs played at antiwar rallies. My folks were into it. They’d tossed out their Frank Sinatra records in exchange for Jefferson Airplane.

One afternoon their friend Eddie Wilson called and asked them to come over to see a great place he had found, an old abandoned national guard armory just outside downtown Austin. Eddie was lobbying for the beer industry but lived for the music scene, and he was constantly devising wild new ideas. As we wandered through the dusty cobwebbed building that was as big as an airplane hangar, he said he wanted to buy it and turn it into a music hall. It was hard to picture, but Eddie had a vision, and sure enough, he gutted the place, and the Armadillo World Headquarters became a central gathering place for progressives, as well as a must-visit stop for musicians around the country. We saw Frank Zappa, Van Morrison, and Bette Midler. It was magical for me. The Armadillo represented breaking every rule and cultural norm. For the first time in my life, I felt like we were part of the in-crowd.

It was in Austin at age thirteen that I had my most formative run-in with the authorities, so to speak. As they had done in Dallas, my parents hung out at the Unitarian church, less for the religion than for finding a community of other liberals. The kids at church, including my oldest friend, Jill Whitten, whose family had moved to Austin from Dallas a few years earlier, had welcomed me to town, and they were up-to-date on all the political activities, especially the antiwar protests. Activists had called for a national Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, with teach-ins and demonstrations to be held across the country. Kids were planning to wear black armbands to school in solidarity.

My family in Austin, 1970: Mom, Clark, me, Ellen, Dan, and Dad, embracing the hippie culture.

Listening to Crosby, Stills & Nash on the record player in my bedroom, I considered whether I too might wear an armband. I was still relatively new to Austin and had spent most of my time just trying to adjust to a new school. We lived in the country, outside of town, and I didn’t know how the other kids would react to my political statement. Finally I decided that it was a good thing to do, regardless of what my classmates might think.

Before going to bed, I dug around in Mom’s sewing kit and found a piece of black felt. I methodically measured and cut it into an armband big enough that it would be impossible to miss. The next morning I attached it carefully to my sleeve with a safety pin and marched out the door, waving goodbye to my parents. As the oldest child, I had always tried to be perfect, and this felt like the most daring thing I had ever done. The armband might as well have had the word agitator sewn onto it. It was sort of thrilling, especially because I was pretty sure I would be the only person in seventh grade at Westlake Junior High to wear one.

Stepping onto the school bus, I glanced around, trying to play it cool, even though my stomach was churning. I found my friend Alison and sat with her. I’m sure lots of kids on the bus had no idea about the moratorium. I knew if there were going to be repercussions, it would be once we got to school. Sure enough, the principal, Tom Hestand, stopped me on my way to third period and asked that I come to his office. I had never been summoned to the principal’s office, and I assumed it had something to do with the armband. I followed him and took a seat in the chair across from his desk.

“Cecile, do your parents know what you’re doing?” he asked sternly.

I thought about it. “I’m pretty sure they do.”

“Well,” he said, “surely you won’t mind, then, if I give them a call.”

I shrugged and watched as he dialed the phone, then listened to it ring and ring. Finally, he hung up. Mom wasn’t home—perhaps one of the luckiest moments in Principal Hestand’s life. Having tried and failed to censure me, he had no choice but to let me go back to class.

Later that evening, when I recounted the excitement of being taken to the principal’s office—escorted by the principal, no less—Mom went ballistic. “Who does Principal Hestand think he is,” she fumed, “trying to intimidate you just for standing up for what you believe?” It felt like Mom and I were in a conspiracy together. The rush was exhilarating. Whether he meant to or not, Principal Hestand definitely gets credit for helping to launch my life of activism. I’ve always wanted to find him and thank him for getting me started!

From then on, it was Okay, now what can I do? Where can I make a difference? A few months later, inspired by the first Earth Day in 1970, I started my very first organization with some girlfriends. We named it Youth Against Pollution. We picked up trash in our neighborhood and collected aluminum cans in the lunchroom. Then I enlisted the help of my brother Dan to crush them for recycling.

My family always had lots of dogs, many of which just sort of showed up. I became obsessed with washing out all the dog food cans to recycle them. Dad found me doing it in the kitchen one day and asked me in exasperation, “Cecile, don’t you know that it’s pointless to wash out all those dog food cans?”

“It’s for the environment!” I protested.

Dad did what he so often did when he thought an idea was harebrained: he told me exactly how he felt, in no uncertain terms. “You’re not going to save the environment by washing out those goddamn dog food cans,” he said, shaking his head. “Don’t you know that companies are going to have to start doing this for it to make any difference?”

Dad thought I was nuts, and that wasn’t the last time. Despite his idealism, he often let me know how impractical I was—and of course I was so desperate to make him proud. It took decades before I began to understand that he must have felt pride all along, even if he sometimes had trouble expressing it. I’m sure seeking his approval helped drive me to try harder. But it also might have been my first lesson in the importance of doing what feels right and not getting too caught up in what others think—including my father. And I guess in a way we were both right. Recycling did catch on, but it had to begin somewhere. I like to think it got a jump-start from teenagers washing out dog food cans.

• • •

Even in Austin, the promised land, there were problems. I was really tall, so logically I wanted to play basketball. But this was before Title IX, the federal law that would guarantee equal opportunity for girls in school activities, and the geniuses who determined the rules for junior high sports made us play half-court basketball. The school authorities must have thought girls couldn’t run the full court. We played six on six, so three of us were on defense, and once we had the basketball, we could only dribble to half court and then pass it to someone on the other side to shoot.

In Westlake Hills, as in much of Texas, football was the entire focus of our junior high and high school. Since girls’ sports were nearly nonexistent, the other option was to be a cheerleader or join the drill team, who performed at halftime at the football games—a sort of high school Rockettes—but I was five-foot-ten, which disqualified me from even trying out for either of them. My mother was outraged, again, but I opted not to take on this fight, since I would rather have died than be a part of the football scene.

Instead, along with friends like Chris Ames, who was a year ahead of me in school and also a troublemaker, we fought against having to go to the weekly pep rallies—demanding a study hall for students who didn’t want to cheer on the football team. At Westlake pretty much every teacher was a coach, so history and science and even sex ed were taught by folks whose primary responsibility was coaching football. As you might imagine, I was a thorn in their side.

Coach C doubled as a football coach and my eighth grade history teacher. It was pretty obvious what his first love was, as he used to give us assignments in class while he drew football plays on the blackboard. When he started Current Events Day, asking us to bring in newspaper articles to discuss, I brought in one about a student who was suspended for shining his shoes with an American flag. I was outraged on the student’s behalf. “Richards!” Coach C yelled, like I was on his junior varsity team. “That kid got just what he deserved!” I never backed down from a debate with Coach C, and he definitely got me to speak up, since I disagreed with almost everything he believed. He clearly shouldn’t have been teaching history. Still, I almost felt bad when he drove the truck full of band instruments under the overhang at the school and peeled the top of the trailer right off.

Although football was the predominant activity in my school, my classmates were also fanatical about hunting. I’d grown up fishing with my grandfather on Lake Waco, catching crappie and frying them for supper. I learned as a young girl how to bait a hook, how to cast and catch a fish. If I caught something worth keeping and eating, Mom insisted I learn how to scale it, gut it, and fillet it. That was the rule, and I followed it. But there was no way I was going to shoot and clean a deer, much less a cow! So I decided in seventh grade that I would eat no more meat, period. I’ve been a pescatarian ever since.

Westlake High was a dead end for me, and after a while I was spending more time trying to figure out how to skip school and raise hell than anything else. I was a good enough student, so my parents decided to move me to St. Stephen’s, a small Episcopal school. It was the first racially integrated school I’d ever attended—and it changed the direction of my life. Suddenly I had the opportunity to learn from really smart teachers alongside kids from different races and backgrounds. It felt like the world was opening up. I threw myself into acting and music and writing—all of which gave me confidence to express opinions and speak in front of others.

Though I loved my family and didn’t know much beyond Texas, I couldn’t shake the feeling that there had to be more. One of the only times I had ever been out of the state was on a trip to New York City with Dad’s mother, Eleanor Richards, when I was in the third grade. We rode the train to St. Louis from Dallas in a sleeper car overnight, and then flew to New York. She took me to the Automat, where you could put in a quarter and get a piece of pie. I had never seen anything like it. We visited the Museum of Modern Art and the United Nations and even went to see Ethel Merman in Annie Get Your Gun. Now that was something. I can hear her voice still today.

Eleanor grew up at a time when women were expected to stay in the kitchen, but she had seen the world. She had gone to Radcliffe College in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and had been to China and India and Africa. She helped start the League of Women Voters in Texas and fought for integration and civil rights. I loved her. More than anyone in my family, she talked about the world and politics and issues nonstop. Even into her eighties we debated everything under the sun, from Middle East politics to premarital sex, which, by the way, she was all for. She told me, “Shacking up before getting married would have been so much better!”

Momel, as I called her, had big plans for me. When I was still in high school she invited me to go with her to London for a week. No one I knew had been out of the country, unless it was to go across the Texas border for cheap alcohol and Mexican food. My mother had strong opinions about everything, including what I should wear to travel to England. I remember a particular red suit that I wouldn’t have been caught dead in anywhere near my friends, but Mom had decided it was what I was wearing.

My grandmother was a big fan of Loehmann’s Discount Clothing Store, so between the pair of us, we were a sight in London. Momel wore a black patent leather raincoat with embroidered daisies, so at least I couldn’t lose her. Wearing our crazy outfits, we went to the theater, took a boat down the River Thames, and visited Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace. When I came back from England I told my parents they were not going to believe what was going on outside Texas.

Meanwhile, every movement of the ’60s and ’70s was coming alive, and it seemed like my parents were into them all. The environmental movement, despite my father’s skepticism over the dog food cans, made a huge impression. We began camping and canoeing on the rivers of Texas, which were continually threatened by dams and development. It was on these adventures that we became close friends with the columnist Molly Ivins, an inveterate camper; Bob Armstrong, the Texas land commissioner; and some singer-songwriters and erstwhile politicians. Closer to home, the fight to save Barton Springs, a beloved natural spring and swimming hole, created a whole generation of environmental activists who fundamentally saved Austin from becoming another developer’s dream.

It was abundantly clear to all of us that Mom had more than her fair share of pent-up energy. She threw herself into one hobby after another. At one point we even raised chickens in our backyard, until the fateful day that one of our many dogs got into the pen and committed the Great Chicken Massacre. (“But just think how happy that dog was!” Mom consoled my brother Dan.) Everything Mom did was larger than life, a full-scale production. But when she discovered the women’s movement, she found her perfect outlet. After all, she’d spent some of her best years taking care of four kids, and she’d volunteered on many campaigns, helping to elect male friends to the legislature. She said that in those days the real sign of a woman’s power was measured by the length of her phone cord at the campaign office.

I was sixteen when a young lawyer in Austin named Sarah Weddington decided to run for the state legislature. She came to Mom, asking for help. It was a golden opportunity for Mom and she seized it. She would gather us up in the backseat of the car and take us to Sarah’s headquarters, where we further refined our campaign skills, learning to phone-bank and door-knock.

Mom came up with one original idea after another for Sarah’s campaign. One of the most ingenious was a new twist on campaigning at the local fair, where voters could enjoy food and music and meet the candidates. Everyone else in the race had a lot more money to spend and they were certain to have more impressive handouts. Mom’s idea was to paste “Sarah Weddington” bumper stickers on cheap paper bags for Sarah to autograph, which people could use to hold all the other giveaways. It was a huge success: by the end of the day, people were carrying Sarah sacks all over the fair.

That was a really tough race, and I saw firsthand just how ugly it could be for a woman to run for office. This was especially true for Sarah, who had made a name for herself at the age of twenty-six arguing Roe v. Wade before the US Supreme Court, the case that legalized abortion in America. Sexism was widespread in Texas politics; her opponent in the Democratic primary refused to call her by name, instead referring to her as “that sweet little girl.” Even some of the local establishment Democrats were organizing against her, doing everything they could to paint her as a radical feminist, literally driving Catholic anti-abortion voters to the polls on Election Day.

Despite all the nastiness, Sarah won the primary and went on to win in the general election by a comfortable margin—the first woman to represent our county in the Texas House of Representatives. Her victory gave Mom the chance to finally get out of the house and go work at the capitol as Sarah’s legislative assistant. This was a profound change, because up until then, it was my dad who got all the notoriety and fame. By then he was a big-deal labor and civil rights lawyer. But even we kids could tell Mom was coming into her own, and we were proud of her. After years of organizing the family, she was putting those skills to use organizing political campaigns, and she was really good at it. For the first time, we saw Mom in charge. It seemed like she knew everything.

Increasingly, as Mom was figuring out her path and my father was filling his spare time hanging out with his drinking and lawyering buddies, I was looking ahead. College was a given, but there weren’t many people close to me who had been out of Texas. Even though I’d been a good student (besides my scrapes with school authorities, which gave me a bit of a reputation), the college counselor tried to dampen my hopes.

Molly Ivins was one of the few women I knew who had gone away to school. She wanted me to go to Smith, her alma mater and the place where she had “worn black and become a radical.” Women’s colleges seemed like a logical option. But then I read about Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, where the Third World Coalition students had taken over a university building and were protesting racism and financial aid cuts. Now that sounded like my kind of place.

Armed with those facts and a copy of the college handbook (my only source of information on the subject), I made an appointment to see the high school guidance counselor, Dean Towner. An imposing presence at school, he always wore a bow tie, and I was not his favorite student.

I sat across from him in his tiny office, excited to tell him what I’d been researching. “Mr. Towner, I’ve heard about some schools I’d like to apply to. My friend Molly Ivins said I might like Smith, and I’ve been reading about Brown and Williams. They all sound like they might be the kind of place I would fit in. I was hoping maybe I could get your help.”

Mr. Towner looked at me over his glasses with a dubious expression. “Well, Cecile,” he replied, “I don’t think those are schools that you’re likely to get into. So I’ve put together a list of schools that you should try instead.”

Like Principal Hestand, he seemed to be trying to take me down a few notches, and I wasn’t going to let him.

“Okay, well, I think I’m going to try anyway,” I said. I picked up my college handbook and left. I figured out how to get the applications and put together some recommendations. I was proud of myself for getting it done on my own.

In those days the college acceptance and rejection letters all arrived in mailboxes across America on April 1. When the day arrived, I could hardly breathe as I walked down the road to our mailbox. Inside was a fat letter from Brown. I tore it open and read that I had been accepted.

I was leaving Texas for a chance to see the world and make trouble. And that’s just what I did.