Sabotage in the Sky

ERICH VON STRAUB resembled very little the stiff Nazi officer who had, so recently, clicked his heels and bowed shortly to the Minister of the Air in Berlin. Then his manner had been perfectly Prussian.

The Minister of the Air in Berlin had said, “Colonel, according to your record, you studied aeronautical engineering in the United States and you speak the language and know the country. We have a great deal of faith in you. I have had you report here to inform you that you are leaving, via Italy, with properly forged passports and birth certificates, for the United States.”

“Yes, sir,” said von Straub.

“The English and the French are depending on the planes of the United States to achieve their air supremacy. Already we have a sufficient number of agents at work in United States aircraft plants, but they are watched so closely that they can do very little. You, Colonel, have always been a man of resource and intelligence.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“You understand that unless this flow of superior planes is at least hampered, we cannot long hope to continue victorious in the sky. We believe that the best method of hampering this flow of planes is to influence English and French opinion of them. Soon we will have the Messerschmitt 118D for pursuit. It has been brought to us that the United States has, in experimental condition, the one plane which will defeat the Messerschmitt 118D. One other plane is nearly equal to it. The British and French are trying to buy these two types of ship. If those planes convince the British and French that they are superior, the manufacture of the Messerschmitt 118D will be reduced in importance. But, Colonel, you are a resourceful man.

“We are not tampering with our production of the Messerschmitt 118D. We will depend upon you to keep the British and French from buying either of these two American planes and then, because 118D is a secret we will maintain with our lives, we will suddenly be able to take over the sky from the English, sweep their isles, down their retaliating bombers, and so bring victory to our glorious cause.

“If you can arrange to convince the English and French that these two American planes are neither safe nor fast, you will find yourself a hero in your own land. Failing that, you will deliver to us a complete plane of each type. Ample funds are at your disposal. The lives of your brother officers depend upon you, so work well!”

“Heil Hitler!” von Straub piously said, turning sharply and marching away.

But Erich von Straub, a man of resource and intelligence, did not at all resemble Albert Straud who had, very recently, been hired as an aviation mechanic by Beryl-Cannard Airlines. Albert Straud was obviously a Teuton, but then so are a large percent of the employees of all aircraft companies in the United States. His blond hair was curly and his eyes were mild and of an innocent blue; he was of medium stature and only passingly handsome; his bearing had no suggestion of the military, but leaned rather into careless ease. He was cheerful and conversational and helpful and, in fact, lived up completely to the fine letters of recommendation he had brought—letters which had been taken from a Boeing man who had somehow managed to get himself killed in an automobile crash.

He stood just now, this Albert Straud, on the apron of the BCA plant’s second hangar and scanned, with a fellow employee, the murky heights of the southern sky—for BCA is only thirty miles from Washington, DC, and shares Washington, DC’s climate.

There was a flash of silver up there and a powerful engine became loud so suddenly that it sounded more like an explosion than an approaching plane. Abruptly the roar stopped. The silver became a low-wing monoplane, stabbing down at the field. And nearly every man on the BCA property froze, drop-jawed and unbreathing.

Planes landing there were too common to be remarked. But two things were different about this ship. One was that it was coming in upside down, and the other, that it probably contained one Bill Trevillian, absent from these parts for nearly four years.

Straight down the runway streaked the ship, the pilot seemingly wholly undisturbed by this reversal of the average state of scenery. And then, almost at the stalling point, when it seemed that he must inevitably crash, he snap rolled! And when the plane’s landing gear was under it where it should have been all the time, the wheels were also being rotated by an instantaneous contact with earth.

There was a furious geyser of dust at the runway’s end and the field was full of a joyous bellow of power—and the silver ship nearly took off again, headed toward the hangars. Another cloud, then the sputter of a cut motor, and there sat the plane, parked neatly on the line, in between two fighting planes, almost touching wings on either side.

“Well, well, well!” said Albert Straud. “I have not seen that since the great Udet. Any idea who the pilot might be?”

His companion, a stocky fellow with a wise eye and a mouth full of tobacco, namely Greasy Hannagan, spat and drawled, “You evidently ain’t never seen Bill Trevillian before, buddy. Him and Udet used to pick handkerchiefs out of the breast pockets of each other’s Sunday suits with their wing tips.”

“Bill Trevillian? Oh, yes. The racing pilot. I should like to know him.”

“You’ll know him all right, buddy. You and me is goin’ to be his repair crew. He’s up here from Mexico to take charge of the BCA 41 Pursuit.”

“Ah. So they’ve been waiting for him before they tried it again.”

“Yeah. They been waiting for him. Hello, Bill, you old scatter-wit!”

“’Lo, Greasy. You wouldn’t be putting on weight, would you?”

“Hell,” said Greasy, “what’s the difference? Ain’t like it used to be, conserving the payload. How you been?”

Bill Trevillian had eased half out of the pit and sat now on the turtleback, his long, booted legs dangling, while he untangled himself from his radio helmet and oxygen mask. He was good-looking in a sleepy sort of way, very tall, very languid, always looking for something upon which to lean his obviously weary soul. Down in his eyes there lay a watchful spark of humor, and upon his lips there always lingered the ghost of his last smile and the beginning of the next.

Bill slid down and looked at Greasy. “Been a long time, huh?” he drawled.

“Four years,” said Greasy. “Where you been?”

“Oh,” said Bill vaguely, “France, Africa, Mexico. Lots of the best bars, Greasy.”

“I hear you were practically rebuilding the Mexican air force,” said Greasy.

“The report,” yawned Bill, “has been grossly exaggerated. Where’s the boss?”

“Cannard is over at Operations,” said Greasy.

“You my crew?” said Bill.

“Sure. I hadda lick six guys when we heard you was goin’ to work for us again, but I got it, no matter how hard I tried to get out of it. This here is the guy that’s been workin’ with me. He’s a whiz on engines. He quotes poetry to ’em or something. Name of Albert Straud.”

Bill looked at Straud and nodded, instantly reserved, not because he saw anything to distrust about Straud, but because Bill was very shy.

“Very pleased,” said Albert Straud with a short handshake. “I hope I can please you.”

“Please the plane and you’ll please me,” said Bill. “Now listen, Greasy, this is Irma. She was built out of four planes and a truck, and she runs exclusively on tequila. Cold cream her, and take the wave out of her tach, and tighten up her left aileron control. She’s fast, but she’s temperamental, and she’s so jealous of me that she tried to kill the last guy that flew her.”

“Okay,” said Greasy, spitting hugely on the tarmac. He then put his hand on Irma’s turtleback and probably would have said something bawdy to her, but a roaring engine suddenly made all speech impossible.

Heads went up and the plane came down. It had cut in to the field past the usual high-tension wires. Evidently it had been flying ten feet above the housetops, for no one had seen it or heard it until it verticaled into the field. Now it shot outward, snapped into a bank which brought its nose to the wind, and slashed with cut gun down the long stretch of concrete.

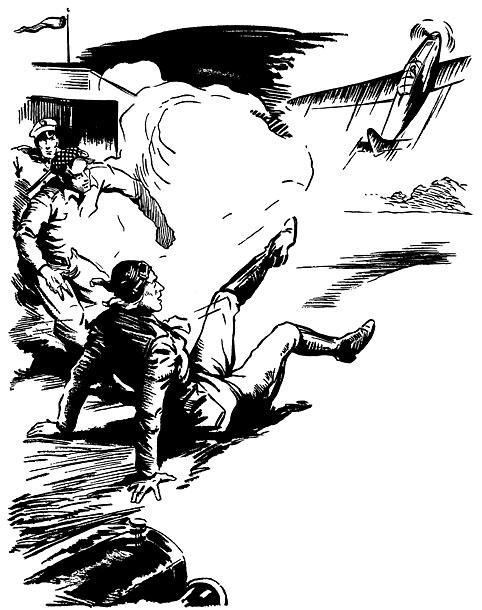

Suddenly the ship skidded to get away from the runway and, leveling out, began to float for a landing. And with one voice, spectators gasped, “The wheels are up!”

Like a bird with its feet tucked up against its body, and seemingly with no effort to put them down, the plane closed the few gapping inches between itself and earth. The engine stopped completely. There came a rending scream of lacerated metal, and dust ballooned skyward, completely hiding the plane.

A crash siren wailed. People began yelling and sprinting. Cars with men on their running boards curved out toward the dust. A fire engine, with asbestos-clad “hot papas” gleamingly apparent upon it, jangled and clanged toward the crash.

But few knew exactly where, in all that dust, the plane had stopped or just how badly it had wrecked itself. It had come to rest about a hundred yards from Bill, and as he was to windward of it, all was plain.

Fearing that the small white tongues of fire might come dancing out from under the cowl at any instant, Bill loped to the side of the ship and wrestled with the hood until he got it open. And by that time it was certain that the plane would not burn.

Two black hands were lifted to black and opaque goggles. The dripping black face became startling as soon as the goggles were raised, for there were white areas, then, about the eyes. A fine spray of oil from a broken line was still bathing the pilot, but the slippery hands could not seem to get any grasp on the belt. Bill unhooked the belt and helped the pilot out.

The danger was over. The ship was only slightly hurt. And the sight of those two white-rimmed eyes in that jet face made Bill—unfortunate Bill—grin.

“Go ahead and grin, you big ape!” snapped the pilot.

And then Bill—poor, unfortunate Bill—did grin. The pilot was a girl. And her voice had so much challenging ferocity and she looked so funny, standing there about five feet two and threatening him, that Bill guffawed. And after all the nervous tension of expecting to see somebody fried alive, he couldn’t stop guffawing. He sank down on the wing, while fire engines and ambulances—all disappointment now—yowled to a halt and raised more dust.

Bill kept on laughing, for the more he laughed the madder she got, and the madder she got the funnier she looked. No one can glare properly when completely inked with oil.

She stomped away to the ambulance, and when the intern tried to help her in she angrily thrust him aside and, taking the sheet off the stretcher, began to wipe her face. She was getting primed for battle and her big sky-blue eyes were full of the lust to kill. But some helping hand had already thrust Bill away from the plane, and so her quarry was lost. Grimly vowing nothing short of the Chinese rat torture, she hung on to a car and so was taken to Operations.

Bill was still chuckling as he finished his instructions to Greasy. And then, “Leave it to a woman, Greasy. No wheels.” And again Bill was laughing.

“Maybe something happened to her wheels,” said Greasy.

“Oh, that’s not possible,” said Albert Straud quickly—a shade too quickly. But he rapidly amended that error. “I have been hearing that those L97s were very good pursuits.”

“L97?” said Bill. “What a flock of new ships there are that I don’t know anything about at all!”

“It’s an X job,” said Greasy. “Newest thing in pursuits.”

Straud was already too interested in Irma to hear.

“The only thing,” added Greasy, “which’ll come close to it is this here BCA 41 Pursuit.”

“What’s a dame doing with a hot crate like that? And an X job, too?” demanded Bill.

Greasy would have answered, but a messenger came from Cannard asking Bill to come over to the office, and so Bill, forgetting about it, slouched along after the boy.

Cannard was surrounded by silver airplane cigarette lighters and a photo-mosaic of the plant and mahogany furniture and Persian rugs and expensive cigars. It was super-modernistic and indicated the affluence which had descended upon BCA with the breakdown of international diplomacy.

Cannard was a lean, nervous fellow with a trick of stabbing people with voice and eyes, of answering questions before they were asked, and getting angry at things which didn’t exist, and pointing with pride and flaming with indignation only split seconds apart. He was the soul and nerves of BCA, and he seemed to think that BCA planes flew only because his own willpower held them up, despite anything his engineers might say or plan.

“Hello, Trevillian. Have a seat, Bill. Glad to see you back. Sit down and have a cigarette. Well, how was Mexico?”

But before Bill could answer that, Cannard was making a wide circuit of the room, pointing to production and profit charts and laying out BCA business the way a machine gunner lays out an enemy charge.

Bill knew all about this. He sat down on the arm of a chair and slumped into it (he never was known to sit straight in a chair, but always across it) and swung his battered boots indolently, looking interested through force of habit, but really wondering if Mamie’s up the road still put out a good hamburger.

“So there you have it,” said Cannard. “Hundreds of planes ordered. Six new ships experimental. Millions rolling in. And the tooling of the plant may bankrupt us. And the British and French are aching to see our 41 tested, and you are the man who is going to do it.”

“What I can’t savvy,” said Bill, swinging his battered boots and gazing sleepily at his cigarette, “is why you sent all the way to Mexico for me. Aren’t there any test pilots left or did they all drink themselves to death?”

“Bill, you know pursuits. For years and years you’ve known hot ships. You’re aces. You’ve got a name. It’s an asset.”

“And the real reason?” said Bill.

“You’ve trained the pursuit pilots into the last wrinkles in three armies. You’ve slammed the hottest planes ever built to first in the hottest races ever flown. You know all there is to know about pursuit, stunts, fast ships—”

“And now the point,” smiled Bill.

“Well”—Cannard nervously leaped into his chair and shook a finger at Bill—“the point is, we’ve lost two test pilots in a month. You’ll find it out quick enough, so I’ll tell you.”

“Thought a salary like three thousand a month looked grossly exaggerated!” said Bill.

“But they weren’t as good as you are—”

“Both killed on the BCA 41,” said Bill.

“Yes. How did you know?”

“Why, you are offering me three thousand a month to test it, aren’t you? And a bonus of ten thousand for successful demonstration to foreign buyers!”

“Trevillian, we’ve always been friends. Bill, you were brought up with BCA. We know that you—”

“Aw,” said Bill, “I know already that I’m the best flyer that ever flew. I’m half-eagle and half-balloon. I’ve got ailerons for thumbs and flippers instead of toes. But listen, Cannard, if I test BCA 41 I’m just an ordinary son of a gun that sometimes can tell the difference between a prop and a hangar—and if you expect miracles—”

“No, no, Bill! It’s a swell ship. It’s okay.”

“Then,” said Bill, swinging his battered boots, “why did it kill two men?”

“Well—hell’s skyways, Bill, you always were the orneriest drink of water, to talk to in the whole game! Be human! I’m on a spot. We’ve got to test BCA 41. Okay. We’ve got to sell her because our BCA 35 is already obsolete. The Messerschmitt 109F can fly rings around it. But we were tooled for thousands of them, and we’ve got to have a ship to replace it. Unless we’re in production on BCA 41 in one month, we’re broke. There’s the honest story. Our bombers have had three cancellations because Lockheed suddenly trebled production and sucked in the orders that should have been ours. We’re in debt to here, understand? And if you won’t test BCA 41 we’re sunk!”

“That’s it, appeal to my old loyalty to BCA, Cannard. Answer me one question straight.”

“Sure. Sure, Bill.”

“Cannard, do you ever recall—now answer this honestly—do you ever recall telling the truth once in your whole life?”

“Aw, now, Bill!” For Cannard was alarmed at the way Bill was moving toward the door.

“I haven’t refused, have I?” said Bill.

“You’ll take it?” Cannard cried.

“I’ll take it,” drawled Bill.

He had opened the door a little and it was left open while he swiftly changed the subject to avoid further praise.

“Say, Cannard, a pursuit job just came in out there. A girl flying it. I believe it’s an L97—whatever that is. How come?”

“Well, I can’t refuse the field,” said Cannard. “It’s a public field. And besides, she’s a good kid, even if she did get engine trouble and have to land here.”

“Engine trouble?” said Bill.

“Sure. She’s a good pilot. She’s—”

“Yeah,” said Bill. “Yeah, she’s a swell pilot. Doesn’t know enough to put down her wheels! All dames are alike, Cannard. They’re daffy in the switchbox!”

“But her reputation—” began Cannard.

“Has probably been grossly exaggerated,” said Bill. And he started out.

The pilot of the L97 was standing at the weather desk in the outer office, viciously busy with a map which she held upside down. She was still smeared with oil from helmet crown to battered boots.

Bill paused long enough to turn the map around for her, and then wandered out to the field. . . .

At five o’clock that evening, as usual, workmen streamed through the gates in a weary river, having been duly showered and inspected. As the flow dispersed to the parking lot and the street and the buses, one man, Albert Straud, detached himself from his companions and unobtrusively eased into a cigar store.

“Hello,” he said cheerfully to the clerk. “A pack of humps and some change for the phone.”

The clerk, quickly producing the cigarettes and the change, could not resist smiling back. “Looks like it’s going to get hotter, don’t it?”

“Hotter before it gets colder,” grinned Albert Straud. “Thanks.”

He went into a phone booth and dialed long distance, asking for Calver, Maryland, and the number of a pay phone there. He glanced at his wristwatch to make certain he had timed his contact properly. He had. He deposited the quarters required.

“Hello, John?” said Albert. “This is George.”

“How are you, George?”

“Not feeling so well. Saw a crash today and for a moment I thought it was going to be serious.”

“That’s too bad. How serious was it?”

And suddenly Albert, seeing he was alone in this string of booths, let his rage go. “Scratched some paint. Broke an oil line. You bungling fool!”

“I . . . I did all—”

“And L97 is still in flying condition! If I hadn’t been on the field Kip Lee chose to land upon, I suppose you wouldn’t have reported your failure at all! You stupid clod! Do orders mean nothing to you?”

“I jammed the landing gear all right, sir. It couldn’t have worked—”

“It didn’t work . . . but that wasn’t enough! When you get your hands on that ship again . . . Somebody is coming. Well, John, I’m certainly glad to hear you’re feeling better. Be careful not to get sick again. You know what the doctor said . . . the next time it may be fatal. . . . Yes, I’m taking care of him. Yes. Well . . . be seeing you, John.”

“Honest-to-God, sir, I didn’t mean to slip up—”

“And give my best to your wife,” said Albert. He hung up.

When he stepped from the booth, the clerk smiled at him again. “Yessir, it sure looks like it’s getting hotter.”

“Yes, it sure does,” said Albert. “Well, don’t take any wooden nickels.” And humming a little song, he sauntered out.

That night, Bill, in Greasy’s roadster, went to Washington. It was a very natural thing for Bill to do, for he was welcome in any embassy and he had only to pick out the one which was throwing a ball that night and then pick out his dress suit from his baggage and roll.

He was in a very happy frame of mind, despite his present job—for Bill was the sort who lasted a long time, and only pilots who never worry last. He rode along whistling badly off key and driving very, very cautiously—which is also a pilot trait—and only occasionally cursing the motorists who suicidally flipped by. He had flown only two thousand miles the day before and three thousand on this day, and he had had a full hour’s rest at the bungalow of Happy Daye, where he had been invited to park that afternoon.

When he got to the embassy, having navigated innumerable circles and “no left turns,” he had a sudden feeling, a premonition, that he was about to enter upon an adventure of some sort. He was not sure what, but only that it would be something nice—not anything humdrum, like breaking his neck.

He was ushered through the glittering rooms and halls, hailed here and there, past groups of bemedaled diplomats, sparkling officers and predatory women, to the bar, where he fortified himself with two drinks of his own concoction which he called a “Flaming Coffin” and which always set bartenders on edge, the suspense of watching for him to explode was so terrible.

Half a dozen air officers of various ranks and nations collected about him and began congratulating him upon the job he had finished in Mexico—which Bill assured them was grossly exaggerated. He had them served several of his “Flaming Coffins” and was forced, shortly after, to go prowling in search of people who could still talk and walk.

And then his adventure happened. A man in the uniform of the United States Air Service, wearing the stars of a general, eased toward him to cut him off. And on the general’s arm was a young lady who— Well, Bill just stopped.

“Trevillian, old boy,” said the general, “my young friend has been in a flat spin ever since you walked in the door and I’ve been recruited to do the introductions. Miss Lee, may I introduce Bill Trevillian. And don’t say I didn’t warn you.”

Bill bowed, staring. For Miss Lee was something upon which a man could stare for hours on end and still be stunned. Her hair, sweeping down in a cascade of yellow to her creamy bare shoulders, made one’s hands twitch. Her fragile little face—too small, it seemed, to hold her gigantic sky-blue eyes—was something to drive a poet into paralysis from sheer wordlessness. She was about five feet two and slender as a boy, and so light that one became afraid to touch her for fear she would break. Her evening gown, what there was of it, was white satin, and it was apparently supported by miracles.

“Oh, Mr. Trevillian,” said Miss Lee, and her voice was such a soothing caress it would have turned snarling wolves into fawning lapdogs.

Somehow the general managed to vanish.

“Dance?” said Bill, swallowing hard and still staring.

“Please,” said Miss Lee.

They danced. They didn’t say a word. They just danced and the music was only for them and the ballroom was an endless vista of altocirrus. For Bill could dance—and Miss Lee could dance!

Someone tittered and they found they had been dancing for seconds after the music had stopped. But even then they were not confused or even brought to earth.

“Balcony?” said Bill, still staring.

“Balcony,” said Miss Lee.

And they went out and stood upon the balcony, with the spring zephyr in her hair and pressing her gown against her, and Bill put his arm about her so she would not be cold.

They looked at the lighted Capitol dome, which was a mound of white ice cream under the stars. They looked at the Washington Monument, an upright icicle topped with tiny spots of red, and decided that Washington was beautiful.

And then Bill began to tell her about himself: what a lonely life he had led, and how cold and alone it was up there in the sky, and how swift, clean wings soared against the flame of far dawns.

“I . . . I’ve never flown,” said Miss Lee.

“Huh? You’ve never . . . Gosh! Look . . . I’ve got a car. I’ll take you out to BCA. And . . . look . . . there’s the moon. We’ll fly straight up into it, just you and me, and leave all this behind us.”

“Oh, Mr. Trevillian!”

Bill, for all his sleepy languor, was a man of action on occasion. In less than an hour they were having a grumbling night crew roll Irma out on the apron and Bill was putting a flying jacket (it had the double eagles of Mexico embroidered in gold upon it and was much stained with use) about her slim shoulders and felt that if he didn’t own the world, he at least held a mortgage on most of it.

He put her into the front cockpit as one might set an invaluable carving into its carefully padded box.

“Now look,” said Bill. “I haven’t disconnected the controls and I shouldn’t be flying with the duals still in, but you just keep your feet away from those rudder bars and your hands away from the stick and all will be well.”

She appeared slightly frightened, but he soothed her and said there was nothing about which to be afraid, that Irma was the best ship ever, even if her ancestry had been grossly exaggerated.

And then they took off.

Irma sent the field, rows of trees, car-lit roads and a sparkling stream fleeing behind them, and with the bright disc of her prop bellowing into the night, stabbed upward at the moon.

Up, up, up, until cities were patches of blurred yellow and the stars were so bright, despite the moon, that they looked like the ornaments on a dowager’s neck. Up, up, up, until the moon was an enormous coin just within reach, and it seemed that they would leave the world entirely and just soar forever in outer space.

Miss Lee seemed to be taking it well, thought Bill. She was a swell kid. She was the best ever. And he felt so masterful and protective that he almost burst.

But at last he had to stop climbing and start down.

He cut the gun, only blipping the engine occasionally to keep it warm, and the whistle of wind in the wings made the night seem mysterious and lonely.

But Bill, for all his protective urge, would not have been Bill Trevillian if he hadn’t decided he really ought to snap roll a time or two. He did. And then he thought it might be a good idea to fly for a little way upon their back, just to show the girl how things looked in reverse, for it isn’t everyone who can stand the Washington Monument and the Capitol dome—both visible, but far away—on their tops.

Upside down. And now Bill pointed Irma’s nose at the field where they had now put on the floods. The girl seemed to be taking it well, up there in the front cockpit. No hands in sight gripping the coaming.

Well, he’d fly straight and not try a stunt landing. And with a touch of stick and a little rudder to steady—Ye Gods!

Bill felt himself go white. There was something wrong! The controls were like permanent fixtures! Neither rudder would give. Neither to the left nor the right could he move that stick! Frozen controls! Neither forward nor backward—!

And there was that brilliant field, its runways glaringly white in the pattern of wheel spokes. There was the lighted T—there were the hangars! Closer and closer!

He strove to cut the engine, but that, too, was beyond touch. The throttle would not move!

Closer and closer—that white pattern larger and larger and Irma making full speed—three hundred and ten miles an hour—

Bill prayed with sudden, unaccustomed fervor and fury. He tried to break the controls loose. He cursed every nut and bolt in the ship.

And up came the field—three hundred and ten miles an hour!

He could feel the sweat starting out all over him. What a flaming crash this would be! And that poor kid up front—! Her first ride—

It was a matter of only seconds. The field was about to be splattered with flaming chips of a onetime ship!

Abruptly, things happened. Seemingly of her own accord, Irma flipped over and upright and the gun was cut. Irma’s wheels reached for earth. Irma fishtailed and lost her speed. There was a welcome rumble of wheels on concrete—

They were down—safely!

Weakly, Bill ground looped and taxied toward the hangar as the field floods went off. Good old Irma! But how the devil—?

He braked her on the apron and pushed back the hood. Very gently he reached into Miss Lee’s cockpit, expecting to find her in a state of collapse.

“Oh, Mr. Trevillian! That was marvelous!”

“Yeah,” said Bill. “Yeah. I guess . . . I guess I better take you home!”

It was warm on the dirt testing field of Lee Aircraft, Calver, Maryland. A few mechanics were crawling over the L97, which lay, much bruised, on the floor of the shop, having been hauled there in the small hours by a truck. She was now minus her complete landing assembly, which was being carefully checked, while other men replaced the dented and ripped plates under the fuselage and fitted a new prop to the engine. Over at one side, the other L97 was on the verge of completion, but the crew at Lee Aircraft was so small that both activities could not go on at once.

Terry Lee, sitting on the white rail of the fence which ran around the tiny operations office, had his bad, stiff leg stretched out to the warmth of the sun. Terry Lee had been a pilot once, back in the days when Gates had knocked the gasps from the paying customers with wing walking and incredible stunting. And Terry Lee had kept going until the time, three years ago, when he had set his last plane to earth, a scrambled mess of junk. But it hadn’t junked his hopes, and it hadn’t kept him away from the flying game. For years he had built racers for his own contesting, and now, if he could build a pursuit plane faster than any other pursuit plane in the world . . .

Kip Lee was beside him, leaning against the fence, one battered boot crossing the other, a new helmet dangling and swinging from her small, capable hand. The sun made her silken yellow hair sparkle. Her big sky-blue eyes were sad.

“Aw, I won’t let it get me down,” she was saying. “But gosh, for years and years and years, ever since I used to sneak my pigtails down a block from home, I’ve carried Bill around in my head, in my baggage, in my ambitions. Why shouldn’t I? You taught him to fly. You made him into about the hottest thing in the air. And that was my ambition. To get so good that he would pat me on the head and say, ‘Fine!’ Well—that’s all over.”

“Come off!” said Terry, her brother. “You must have looked funny, and, anyhow, you got your revenge—”

“Yeah? I land without my wheels. I couldn’t get them down. And then he laughs at me like a baboon and tells everybody ‘dames can’t fly.’ All these years, all I’ve lived for was to have him give me a big smile and say, ‘Fine!’ And he laughs at me! Why, I used to tag that idiot around like a pup, hanging on every word he said! And last night at the embassy he didn’t even recognize me. Not even when I was introduced as ‘Miss Lee’!”

Terry shrugged, but his eyes were sympathetic on his sister.

“You’ve changed a lot. You’re a magazine cover now—and then you were just a gawky kid with pigtails. And freckles. How should he know?”

“Yeah? He’s a swell-headed sap, that’s what he is. I could kill him!”

“From your account of last night, you darn near did.”

“Yeah.”

She smiled a little, remembering how scared Bill had been, lifting her out of that ship. But still it was not revenge enough. To laugh at her and say dames couldn’t fly and—“I hate him!” she cried suddenly, tears stinging her eyes.

Terry’s oil-burned old face softened as he pulled her toward him. “Look, kid. Bill’s all right—”

“Then why didn’t he ever get in touch with you after you crashed?” she flared. “And here you are trying to put over the 41 and he’s come up to test the only crate that can edge you out. Yeah, sure, he’s all right—except that he doesn’t know his own friends when the world begins to sing songs about him!”

“Sure. He’s got a good job,” said Terry, fishing for his pipe. “He rates a good job. What could I pay him? Besides, I haven’t told him what I was doing. He doesn’t know that Lee Aircraft and Terry Lee are one and the same.”

“He’s stupid if he doesn’t guess!”

“Look, honey! Bill knew I crashed!”

“He did. Sure he did.”

“He wired two thousand dollars to my hospital. And he’s written me three or four letters since that have been forwarded to me. But until I can pay him back or offer him something—”

“Then he doesn’t know?”

“No. And why should I tell him I’m shoestringing it here? I can’t let him sink his last dime into such a place.”

“But he’s testing the one plane—”

“Yes. And if he found out he was competing against my ship, he’d quit, and then he would be out a lot of money. So he isn’t going to know if you and I can help it. We’ll make this 97 job strut its stuff, and we’ll beat out BCA’s 41. I can design ’em, and you can make ’em sing in the sky.”

And then she remembered Bill standing there, laughing at her again. And she heard, once more, his remark to Cannard about “dames.” And she suddenly jammed her helmet on her head and started toward Hangar Two, where an Airdevil Sportster sat.

“Whither bound?” said Terry.

“Any harm in going down and watch the 41’s first tests?”

Terry grinned.

“And I still think he’s a conceited ape!” she flung back at him.

At noon a messenger found Bill sitting on a dolly under a No Smoking sign, lazily puffing upon a cigarette. Bill was outwardly his calm, indolent self, but inwardly he was still asking questions that went unanswered. Irma had little stability. Irma was the cousin of a truck, the sister of a banshee, and the daughter of ill-assorted crates. Why had she, at the very last instant, decided to fly herself? Irma certainly had never done it before.

“Mr. Cannard says he wants to see you, Mr. Trevillian. I guess you’re going to start hopping 41, huh?”

“Yeah,” said Bill. “Hey, Straud!”

Albert paused on Irma’s catwalk, a monkey wrench in his fist and grease upon his cheerful face. “Yeah?”

“You find anything wrong with the controls yet?” said Bill.

“Not a thing,” said Albert.

“Huh,” said Bill. And he got up to tag the messenger toward a group of engineers and officials who were gathering for the slaughter.

“Is he goin’ bugs?” said Greasy, taking a fresh chaw. “These controls are perfect, and yet he’s got us going over ’em again and again, when we ought to be tuning up the crate for him.”

“Yeah,” said Albert.

BCA 41 was already on the line, 1,200 hp Allington engines muttering promises about what it was about to do to a couple of innocent clouds which drifted unconcerned in the deep blue of the sky.

“Are you all right, Bill?” said Cannard.

“Yeah,” said Bill.

“Now look, Bill—we’ve got all the bugs we could think of out of 41. She’s a sweeter ship than the other two we built of her type. She’s fast and she’s able, and she’ll outfly—”

“Yeah,” said Bill, “but maybe it’d be a good idea to let me find that out for myself.”

“Sure, Bill. Hell, yes! Well, there she is. What’re you going to do?”

Bill looked sleepily at the plane and then at the tense engineers. And the engineers looked at the plane and then at Bill. There was little love lost—there never is—between the swivel chair and the cockpit, where design was concerned. The engineers looked both anxious and jealous as Bill started to go over the plane as though somebody might have forgotten a ship needed wings.

BCA 41 was extraordinary in the lack of resemblance to the usual pursuit job. Instead of being a compact set of wings, fuselage and engine, streamlined to the nth, it was really two ships. Each of the two engines swept back into a tail, and the fuselage was just a Plexiglas bomb between the engines and the outriggers. The wings swooped sharply up at the ends, in an attempt to give her stability, and were hugely slotted, to cut her landing speed from the hundred and ten miles per hour it might have been to the sixty-five it had to be.

The pilot’s cockpit was out in front, with visibility all around except back and down, but the gunner’s cockpit, back to back with the pilot’s, commanded this blind spot. The thing would mount eight machine guns in the wings and a motor cannon, 20 mm, firing through the hub of each prop, as well as a double Lewis firing straight aft.

The idea looked sound, for no other ship could get directly on its tail; and as, between them, pilot and observer could see all there was to see, it was doubtful if she could be suddenly attacked without warning. From a war pilot’s viewpoint, she was all a plane should be. But just now the question was, could she stay all in one piece in the sky?

Bill looked into things and kicked things and shook his head as though very sad about the whole affair. The engineers jittered. Bill frowned and pursed his lips and thumped the wings. The engineers muttered. Bill listened to the idling Allingtons and sighed. The engineers appeared ready to take off themselves, ship or no ship.

Greasy and Albert Straud helped Bill into his chute. And then Albert pitched a hundred-and-fifty-pound sandbag up to a greaseball, who grunted and lowered it into the gunner’s pit. Albert got up and lashed it down.

“Well,” said Bill, “personally, I’ll take vanilla.”

The engineers frothed.

Bill slid into the forward seat and unlocked the controls. He wabbled them, looking around to see if all the flippers and rudders worked, and was apparently disappointed that they did. He revved the engines into a frightful din and watched the panel, with all its countless faces, for a story which also seemed to weary him. He slid open the hood again and beckoned urgently to the engineers, who instantly forged up against the blasting slipstream, ready with a thousand explanations as to why something wasn’t working.

“Say!” shouted Bill against the yowling motors. “If Begging Baby wins the third at Bowie, will you radio it up to me?”

The engineers properly reduced to a gibbering frenzy, Bill took to the runway.

With haunted eyes Cannard watched him taxi BCA 41 up and down the field, testing out her horizontal control. This went on for fifteen or twenty minutes, while the dust from beside the concrete strips drifted higher and higher under the blast of the props. Bill would speed up and then slow. He would ground loop and come back again.

Finally he drifted to a stop before the group and beckoned up the mechanics.

“Left rudder feels slacker than the right,” he said, standing on the catwalk and smoking a cigarette. The mechs promptly made the adjustment.

An Airdevil Sportster floated in for a landing and taxied out of the runway to the line. Bill climbed back into the pilot’s seat and closed the hood.

Cannard again watched with twitching lips and dilated eyes. Bill took the 41 to the east-west run and, kicking her into the wind, gave her full throttle. The blast was enough to blow down the hangars. The 41 leaped ahead so fast that it blurred. It lifted ten feet, and then the engines were cut and again its wheels touched. At the far end, Bill came to a braked stop. He taxied back to the group.

“Tab control seems stiff,” he said, getting out for another smoke. “Ease it up, will you?”

The mechs eased it up, and once more Bill taxied out to the east-west run. And this time, when he javelined into the sky, he kept on going.

Quickly building a little altitude, he banked gently to the left and then to the right, but by that time he was out of sight.

“Gee!” said an awed voice at Cannard’s right. “That thing sure travels!”

Cannard glanced aside and then away before he realized who it was. “Oh, hello, Miss Lee. Come to do a little spying, huh?”

“Yeah,” said Kip Lee. “And I’m discouraged.”

“Ha!” said Cannard, with no mirth whatever. “Where the hell has he gotten to?”

There was a rushing drone which swiftly became a bellow and Bill was over them and gone once more.

“Gosh,” said Kip. “I’m not only discouraged, I’m groggy!”

“Ha!” said Cannard. “What the hell does he think he’s doing—taking a sightseeing tour of Virginia?”

“That thing must make five hundred and fifty miles an hour,” said Kip.

“Yes. Hey, Tom! Radio Bill to come back!”

But before Tom could contact the ship on his portable field set, Bill was overhead again. And even those in the crowd who knew little about the way planes should fly could see that something was wrong!

Bill tried to bank into the runway and then shot skyward again. He verticaled and once more attempted to shoot a landing. His wheels were down and his gun was cut, but again he failed. The 41 went racketing out of sight into the horizon haze and appeared once more, heading in downwind!

“He’s crazy!” wailed Cannard.

Downwind! And his wing slots were apparently closed. He was doing a hundred and ten in the air with both guns cut and props nearly still, and the fifteen-mile breeze boosted it to a hundred and twenty-five ground speed! And the ship was not even headed for the runway, but for the rough strips in between!

Kip’s fingers sank into Cannard’s arm and Cannard didn’t feel it. Nobody breathed. The plane wasn’t going to make another try. This would be it!

The engine of the crash wagon started. Hot papas got into their helmets and girded themselves to haul a fried pilot from a blazing wreck. Some people were already running forward; others were frozen to the earth.

Downwind at a hundred and twenty-five! And he was leveling off for a landing with half the field used up already—leveling off a full fifteen feet above the ground. The plane came down to stalling. It floated, devouring landing way at a terrific clip, seemingly eager to get at the high-tension lines and the fences which waited at the far end.

Abruptly plane and shadow met. The ship bounced and was forced back to earth. Again it bounced and came down on its tail wheels, hitting its gear and tipping up until it was impossible for the props not to clip earth. With two sharp pings they did. Then all wheels were down, and the fences and wires were only feet away. The plane ground looped, rocking up to knock an aileron against the dust. It settled back and coasted slowly. It was trembling like a horse that has missed a hurdle. . . .

Kip began to breathe again. She felt too weak to run, but she found herself running. She felt dizzy and ill, and at the same time glad.

She grabbed the tail of the crash wagon as it shot by and clung on until it skidded to a halt beside the battered plane. She leaped down and was up on the catwalk, tearing at the hood, before any other had begun to approach it afoot.

And then Kip stopped. She had the hood open and a string of profanity came smoking forth. And Kip began to grin.

Bill was a wreck. The oil line to the gauge had parted company, nearly drowning him in a bath of hot oil. He was black—all black. When his streaming hands reached up to shove away his goggles, his eyes, surrounded by two white rings, glared forth.

He saw Kip. She had thrust her helmet into her pocket and the sun was in her yellow hair and her big sky-blue eyes were gleaming with glee.

Bill was shocked down to the darkest recesses of his soul. Suddenly he saw it all. This was the one who had landed on the field. And the girl at the embassy. And the frozen controls—Irma—

Bill grew angrier and madder and angrier.

And Kip laughed. With one wild yelp of mirth which could no longer be held in check, she laughed. And she kept on laughing.

“Dames—” she sputtered. “Dames can’t—fly!”

Bill tried to mop away the oil. He climbed out on the catwalk with every intention of throttling her. And she nearly fell off the leading edge.

“Dames—dames—” wept Kip, “can’t fly!”

Then some kind soul averted murder by pulling Bill toward the ambulance. . . .

On the following day, Greasy Hannagan, wandering into the third hangar, was startled by a pair of boots sticking out, feet up, from the pilot’s seat of the BCA 41. The boots were battered, but obviously from the best Italian shop. There was only one pair of boots like that anywhere about the field, and as that pair belonged to Bill Trevillian, Greasy came to the brilliant conclusion that Bill’s feet must be in the boots and that, therefore, Bill was upside down in the BCA 41 third ship. Yes—from the occasional mutters of profanity, it was Bill. Had to be Bill.

Greasy took a chaw and sat down on the wing. After a little, Bill came struggling forth. There was a long lot of him to extricate from that position and it took some time. But finally there was Bill, upright again. In his hand he held a gauge which he had pulled from the back of the panel. On his face was an angry cloud.

“I got it,” said Bill.

“What?” said Greasy.

“The oil pressure gauge. On the ship I nearly smashed yesterday, there was nothing whatever wrong with the panel. I have the photographs of the readings from the automatic camera, and I can’t see a trace of warning for the breaking of that oil line.”

“Well?” said Greasy. “A faulty line, that’s all.”

“Yeah? Well, it isn’t all! This gauge here has been opened since it was installed. The little clips here show abrasions made after the instrument company gave it the final coat of paint.”

“I don’t get it,” said Greasy, frowning.

“It’s open and shut,” said Bill. “And right now I am making sure.”

He took the air hose off the paint sprayer and, with reducers, made it fast to the back of the gauge. There was already one gauge on the air hose, an accurate one, tested every week. Bill shot on the air. The gauge in his hand, which he had taken from the third BCA 41, registered a pressure of sixty pounds. The air gauge contradicted it to the extent of thirty pounds, for it registered ninety.

“There!” said Bill.

“I still don’t get it!” said Greasy.

“Look,” said Bill. “This oil gauge is set to register far less pressure than is actually in the lines. That means that the oil pumps are set way up and it won’t show on this gauge. Now do you see?”

“Nope,” said Greasy.

“Listen, dummy! If a pilot sees his oil pressure going up, he revs down. If the oil pressure goes up and he doesn’t rev down he either breaks his line or spoils his engines. The chances are that the line will break as it comes into the panel, or that the face of the gauge itself will go blooie. In either case it is certain that the lines will break under enough pressure. And either the pilot is blinded or the hot oil catches fire. Now do you get it?”

“Gee!” said Greasy.

“So that crash yesterday was all laid out for me in advance!”

“Gosh, who’d do a thing like that?” said Greasy, blinking.

“I’ll tell you who. The only rival BCA 41 has is the L97.”

“Aw, naw!” said Greasy.

“Aw, yes!” snarled Bill. “Maybe it was a setup for a gag, and maybe it was with malice aforethought to sabotage this ship and put over the L97. But that Lee kid is behind it!”

“Aw, hell!” said Greasy. “You’re off your crankshaft! Miss Lee is a good scout. She’s aces. She wouldn’t—”

“Yeah? Well, when a ten-million-dollar contract is at stake, people will do anything.”

“You’re just all het up because she laughed at you,” said Greasy. “Well, hell, Bill, you laughed at her first!”

“I didn’t try to wreck her ship first.”

“Aw, look, Bill, Miss Lee—”

“Where are they building the L97?”

“Calver, Maryland. But look here, Bill, you better not—”

“A ten-million-dollar contract,” said Bill, “is enough to make anybody do anything. I was wrong about her. I thought she was swell down at the embassy and I was willing to lay down my life—”

“You met her someplace else?”

“Yeah. In Washington, worse luck.”

“Oh, so it was Miss Lee that was out here flying with you night before last. News, you know, gets around.”

“So what?”

“I don’t know who it was. The hangar man said she was with you and came back to get an evening bag that she left in your ship—”

“What’s that? She came back here?”

“Sure. You go past this place to get to Calver, and she drove in and asked to get her evening bag. The hangar man—”

“So! She came back!”

Bill was already on the phone, dragging the night hangar man out of a well-earned sleep. “Look,” said Bill, forgetting that that is hard to do through a phone, “this is Bill Trevillian. The other night I came out here with a girl and I hear she stopped back to get her evening bag. Clean the cumulus out of your wits and remember. How long did she talk to you?”

The hangar man mumbled, “Oh, about half an hour I guess. She sure knew her planes.”

Bill hung up. “So! She talked to the hangar man for half an hour. A good mech, working fast, could jim that pressure gauge in that time and set up the oil pumps. She came in here and covered—”

“Aw, you’re loopy!” said Greasy. “Miss Lee—”

“Ten million bucks and a laugh!” said Bill, now white-hot. And he flung himself out the door and into Greasy’s roadster and went streaking past the startled noses of transport planes. His tires screamed as he careened out into the highway, Calver-bound.

“He who laughs last laughs and laughs!” snarled Bill.

Back at the hangar, Albert Straud drifted up. “What’s wrong with Trevillian?”

“Aw, he’s in a spin. Look, Albert, get a gauge—this one’s been monkeyed with—and install it in the third ship there, will you?”

Albert looked up at the gauge and then at the plane. It was nearly noon, but he worked calmly. When the whistle blew he went with the others out through the gate. According to his watch he had two minutes and a half to make a contact.

“Sure is hot, ain’t it?” said the clerk.

“Yeah, sure is,” said Albert, slipping into the booth. “Get me Calver—” And then, “Hello, John, this is George.”

“Hello, George.” And he could not resist adding, “I hear you had a little trouble with this and that yesterday.”

“Shut up! Trevillian is on his way to the Lee plant. You’ll spot him because he’s lanky and sleepy-looking, and maybe you’ve seen his pictures. He found the altered gauge on the third ship and he’s laying the blame on Lee Aircraft—”

“Good. L97 goes up for altitude this afternoon. A lot of officers here. There’s enough altocirrus for ice, and the de-icers are short-circuited.”

“We’ve got something going,” said Albert. And, hearing someone enter the next booth, “Well, John, I hope you make the grade all right. I gotta eat. S’long.”

“I’ll make the grade,” said John. “’Bye.”

There were a lot of officers at the Lee plant, and the fence which ran about the tiny operations office looked as if it had been decorated with all the braid in existence. French and British aeronautical experts chatted together in low voices, from time to time hopefully glancing toward the line, where three mechs were giving the L97 its final check. Terry Lee hobbled among them answering questions and beaming, nearly bursting with pride at the thought of what his precious baby, the L97, was about to show them.

Kip, in white boots and breeches and shirt, had drawn all the junior officers into her vicinity and they nearly shattered themselves each time she indicated that she needed a cigarette.

“Well, Lee, old chap,” said a British colonel, “if it does all you say it will do—and don’t think we aren’t hoping it will—why, there will be a lot of changes around here, eh?” And he waved his seat-stick in the direction of the weed-grown field and the sagging old hangar and machine shop which had gone six years without a coat of paint. “But what I can’t understand is how you’ve managed to research and build the two ships you have built.”

“I researched ’em in the sky,” said Terry. “And I pawned my grandmother’s false teeth. I’ve wanted to build this plane for years, but it hasn’t been more than six months since they finally got out a twenty-four-hundred-horse engine. That was all she needed.”

“I say, aren’t you a bit squeamish about letting your sister fly it, though? It’s an X job—”

“Kip?” said Terry with a laugh. “Why, Kip cut her first teeth on a rip cord ring, and that’s a fact. She was flying in planes before she could walk. They don’t come better than Kip.”

“Yes. Yes, of course. I know she’s won races and stunting exhibitions and all that, and I’m not questioning either her reputation or her ability. But it is, may I say, a rather dangerous thing kicking a killer like that around the sky.”

“Never mind,” said Terry. “I built it and I know it’s right. And she saw it built and knows every bolt in it.”

The colonel looked at Kip—who could barely be seen inside the ring of junior officers—and shook his head in wonder. A slight little girl like that and a ship which might make five hundred and seventy-five miles an hour—! Strange people, these Americans.

A battered roadster braked to a screeching halt and out of the dust stalked Bill Trevillian.

Two officers recognized him instantly and spoke to him, but Bill went right on by, too mad to see anyone but Kip.

With all the junior officers helping, she had gotten into her parachute harness and was being lifted up to the pit. By the time Bill arrived, she had pulled on her helmet and buckled her belt and the junior officers were all backing up to avoid the slipstream of the gigantic prop. She looked like a little doll put down in the midst of gleaming, lethal machinery to be torn to bits, but the picture had no meaning for Bill. She was jabbing at the throttles when he vaulted up to the wing and yanked back the hood.

“Hello,” said Kip. “What’s the idea?”

“You know what the idea is,” said Bill. “I found that gauge one of your pals jimmied up!”

“Huh? Say, you’ve sprung your prop! What do you mean, ‘gauge that one of my pals jimmied up’?”

“Sure, act innocent!” said Bill. “It was a good joke—only it might have killed me!”

“Mister Trevillian,” said Kip, “if you don’t get off that wing and stop talking blather—”

“Sure! Pretend you didn’t fix that gauge so I’d get oil in my puss! Sure! Pretend you aren’t doing your bit to help your company get the contract away from BCA. Yeah!”

And now she was mad. She was as white as her shirt. “Why, you thick-skulled—” And she blotted it out by jamming the throttle into the board. The blast from twenty-four hundred horses was enough to tear a man in half and Bill hadn’t had any too good a grip on the hood. He was bowled off the wing like a rag in a hurricane. And then the junior officers had him.

He was bowled off the wing like a rag in a hurricane.

Kip closed the hood with a bang and, without so much as a wave at the spectators, shot the big pursuit off toward the runway.

Terry Lee limped forward and rescued Bill. But Bill was still too angry to see or think about anything but Kip, and he was led all the way back to the fence before he realized that the voice on his right was very familiar. He turned with annoyance and then, suddenly, recognized Terry Lee.

“Thought you’d get around to it by and by,” said Terry. “How you been?”

Bill looked at Terry and then at the stiff leg. “Why—I thought you were still flying someplace. What’s the matter with you?”

“They say,” said Terry, “that me’n planes are through so far as the sky is concerned. I’m building them.”

“You . . . you’re Lee Aircraft—! Good lord,” cried Bill, “I never connected them up . . . never once!”

“Well, there are plenty of Lees in this world.”

“But you—then you’re the one that’s building the L97—that L stands for Lee!”

“Yep.”

“And then—then Miss Lee is Kip Lee!”

“Sure.”

Bill’s face was scarlet.

“Oh, my God! Say, I’m in a spin—a flat spin! Oh, lord, have I made a fool of myself! Why doesn’t somebody tell me these things? Kip! Why, I haven’t seen her since she used to steal my tools to build dollhouses. What a change!”

“Yeah, isn’t it,” said Terry. “You know, her one ambition has always been to get as good as you are, Bill. She’s got every newspaper picture of you that was ever published. And she’s damn near made good her brag.”

“Oh, I’m a split-tailed jackass!” said Bill. “Terry, you’ve got to square this. You know what I just did? I accused her of fixing my oil pressure gauge. It caused my crash yesterday, and I thought, because I laughed at her, she pulled a gag or was trying to sabotage BCA or— My God, Terry, you’ve got to square this! Kip, little old Kip—”

“There she goes!” cried several in the crowd.

Everyone, down to the field cat, was watching the L97. The ship was something to look at, too, for it accelerated so fast on the takeoff that eyes had to jump ahead of it to see it at all.

It was of a different design from the BCA 41, in that it followed a more conventional pattern, having but one tail and one engine. It covered its blind spot behind by having its gunner’s pit nearly up against its rudder and gun mountings so fixed that a gunner there could cover all but the smallest possible area below. It would carry ten machine guns and one rapid-firing motor cannon placed through its crankshaft. It saved the weight of duplicated fuel lines and cylinders required for two engines, and for that reason could probably cover more air faster than the BCA. And that gigantic engine was hauling it aloft now at the climbing rate of a thousand feet in ten seconds, a black bullet fired straight up.

“I say!” said the colonel, blinking into the sun. “That thing can’t be fully equipped and fully loaded!”

“With guns, ammunition and gas,” Terry assured him. “Just as if it was going up there to shoot down a Dornier.”

The point caught the colonel’s fancy and he smiled a pleased smile.

But Kip wasn’t smiling. Her face was stony and her knuckles on the stick were dead white. The jets of white flame from the exhausts were as nothing compared to the jets which stabbed from her eyes.

Saboteur, indeed! The big baboon! To accuse her, Kip Lee, the kid who had idolized him, of sabotaging his lousy ship—! And straight up went the L97, straight up at the altocirrus which spread a lacy, delicate pattern seven miles above the earth.

Behind her the field fell away with such shrinking rapidity that people became dots and then barns became dots, and finally fields became dots. The murky horizon stretched further and further until, ever so slightly, the curvature of the earth became apparent.

She jabbed an oxygen tube into her mouth and turned on her heat, for it was getting colder as she streaked up, and at four miles a man finds it impossible to breathe.

The superchargers in the giant engine were whining shrilly and the automatically pitched prop twisted as it tried to get a bigger bite out of rarer air. The plane was all power and flash and sound, and now, at twenty-five thousand, it was still going up at the rate of twenty seconds per thousand feet. Fastened against the panel before her were the sealed barographs the French and British had had installed, for they trusted no instruments but their own. And by this time the plane was wholly invisible in the sky, except to powerful glasses.

The stratosphere pursuit showed no sign of wanting to quit at thirty thousand. Kip, still mad, automatically checked over her instruments and automatically registered the tale of every flickering needle. All was well.

Thirty-one thousand, and the first wisps of cirrus, featherlike strata of ice crystals, were shredded by the wings. Kip switched on the de-icers.

Thirty-two, thirty-three, thirty-four, thirty-five— The earth seemed milky, seen through the sheets of clouds, and the horizon was too thick to be visible.

Thirty-six, thirty-seven—

Ever so little, the ship began to complain about it. The engine heat started down slowly. The controls were a little sloppy. Kip sat forward and leveled out. She’d let this demon take a breather and then try to push it another thousand or two. Her eyes wandered to the earth below, but the earth was only partly visible, a detached and unimportant thing which one found with surprise.

At a lessened climbing angle, she again nursed the plane higher. Thirty-eight, thirty-nine— It was trembling, seemingly ready to stall. The controls were wabbly—

Too wabbly! And then too stiff!

Kip forgot her anger in that second. She saw the right aileron bent down and could not bring it up. It was caught! Ice! The whole leading edge of the wing was thick with frost! And ice had gotten into the hinge of the aileron.

The ship twisted slowly over on its side and then, with a suddenness which left her heart a thousand feet above, curved like a slashing sword and, nose at earth, engine screaming as it revved, headed down!

It was a tight spiral which gradually wound into itself. Kip worked at the aileron with the stick, trying to ease it loose. The earth had turned into a kid’s top and all the colors blurred into a monotone, so fast was it going round. She cut her gun, but this plane was more a bullet than a well-behaved ship and the speed indicator was already getting up toward terminal velocity—and keeping on upward. Six hundred, six-fifty, seven hundred, seven—she was going at the speed of sound! Going straight down, and she’d crash before the passage of her plane was heard. She’d dig even before the scream of her wretchedly protesting wings told of her plight!

She coolly worked at the aileron. It was warmer in these lower strats, but not warm enough to melt that ice. And as she went she picked up a heavier and heavier layer of white death.

Twenty-six thousand, twenty-five, twenty-four, twenty-three—

Around and around, like the blade of an electric mixer. There was still a chance. But she knew better than to try to bail out at this speed, for the air out there would be like ten hurricanes added into their total speeds and her head would be snapped and her back broken before she could ever get free.

She looked at her ammeters and noted that they were registering no current drag. Somewhere, probably in the de-icers, wires had burned through. She had failed in one respect. She had not noticed those ammeters in time to know that her de-icers were not functioning.

Nineteen, eighteen, seventeen thousand feet. Still three and a half miles high and going earthward at six hundred feet a second. In less than a minute—

She hauled back on the stick with all her strength and her arms were almost yanked from their sockets as the plane began to flatten its spiral into a spin. The ASI went mad now, for it could not register speed with the tail flying about in a wider arc than the motor. She brought the thing up to a stall and then let it fall out. Again she flattened the spiral into a spin and whipstalled out of that. Anything for a little delay. And it came to her, as the blood rushed downward from her head with each attempt, that this plane wouldn’t need any gravity tests if it withstood this—for the maneuver was one to wrench out any bolt that could be wrenched.

Delay—delay! Just a few seconds, here at eight thousand feet, and that aileron might let go. Whipstall, spiral, spin. She was getting dazed with the beating she was taking, for she was being buffeted all about, and even with the long practice she had had, she could not fight off dizziness forever.

Whipstall with a vicious swoop and into a giddy spiral. Flatten the spin, stand her up on the nose, swoop off and into another spiral. And each time she fought to get the aileron free.

She wondered what they were thinking about all this on the ground. She really ought to make a note, in case she didn’t survive it. Then Terry would know that something had to be done about the de-icers—

With a jolt that sent the ship hurtling into a reverse snap roll, the aileron gave way. With the speed of instinct she brought the plane level and cut in the engine. The Allington sputtered coldly after its long idling, but it took hold and she went rocketing across the fields, looking for the port.

Somehow she eased into position and lowered her wheels. Somehow she floated to a stall and touched three points at once. Somehow she kicked rudder and got the plane to the line. And then she fainted.

Bill, losing his languor, pushed some junior officers in the face with his right boot and yanked open the hood. Anxiously he lifted Kip’s head. She had bitten the oxygen tube mouthpiece all the way through, and now it fell from her lips. Bill pulled up her goggles.

Sleepily she came to and saw him. A smile crept over her face and dreamily she said, “Oh, Bill—”

“You’re okay, Kip. Altitude silly, that’s all. And gosh, I’m sorry! How was I to know you were Kip? Gee, I feel so bad about it I—”

It was like sticking a pin into a black panther. The whole memory of it came back to her and again his angry accusation was ringing in her head.

“So!” cried Kip, throwing off her belt and standing up so suddenly that she almost knocked him down. “So I sabotaged your plane, did I? Well, how about my plane? How about my de-icers? Yes—how about them? Just because you thought in that evil, crawling mind of yours that I had something to do with your rotten flying, did that give you the right to short-circuit my de-icers? Get out of here! Get out of my sight before—before I turn these machine guns on you!”

The junior officers again hauled Bill down and hurried him to his car, no matter how he struggled.

“And stay out!” Kip shouted after him.

And then she sank down into the pilot’s seat again, and despite all the praise she was getting and all the bravos about the plane—for they had not seen her come down at all—she held her face in her hands and wept big, bitter tears.

The BCA 41 streaked across the field. It verticaled, five miles away and back again, before a spectator could take a breath. Abruptly it snap rolled and went from that into a straight climb, and when it fell out of that it did an inverted falling leaf for three wriggles. It was a bullet that was being fired from all directions, and trying to track it by its sound would have driven a man mad; for very often it was there almost as soon as its own sound was, and very often it was there and some other place before anyone could see that it had been anywhere in the first place.

“What the hell is the matter with him?” said Cannard. “Here! There! Up! Down! On his back and his belly, and picking daisies with his wings one minute and clouds the next. I’m tired of looking at the damned fool!”

Greasy spat philosophically. “Well, if you asked me, I’d say he was trying to work off the williewoofs.”

“The what?”

“The whizzlejits.”

“You mean he’s mad?”

“I mean he’s revved up till his mount bolts is coming loose. He’s been like that all week. Ain’t you seen it?”

Cannard was getting dizzy jerking his head to the left and right following the silver flashes. He turned his back on it, lit a cigarette and then threw it away. He swung some keys around and around on a silver chain and then jingled some pennies and nickels in his pocket.

“He did his tests all right for the British. Came through fine,” said Cannard at last. “If the finals go all right, he’ll get ten thousand bonus. So why the hell has he got the whizzlewoofs or whatever you said?”

“Girl trouble.”

“Who? Bill Trevillian? Nuts, my friend. Not Bill Trevillian!”

“Yep,” said Greasy, renewing his chaw. “’S’fac’. And she don’t like him.”

“Not like Bill? Say, that girl needs talking to—she must be crazy!” He dug the engine snarl out of his right ear and glanced with a wince at the BCA 41, which had just made the wind tee spin on the Operations office roof.

“Yep,” said Greasy. “She’s crazy. He came back here day before yesterday with a black eye. Not much of an eye, but it was black all right for a while.”

“Black eye! You mean she slugged him?”

“Wouldn’t be surprised. Maybe threw a wrench at him.”

“A wrench! Say, look here, Greasy Hannagan—”

“I said a wrench.”

“Who the devil—?”

“Kip Lee.”

“Who?”

“’S’fac’,” said Greasy. “Dunno what the trouble was exactly, but he got the idea she monkeyed up his crate and went roaring over full gun to zoom the place. I told him he was yelling up the wrong tree.”

“Monkeyed up his plane? Say, am I in charge of this place or have I got BO? You mean to say somebody—”

“Yeah. Fixed a pressure gauge and the oil pumps. That was what caused his first crash—or almost caused it. And he said—”

“Kip Lee wouldn’t do a thing like that. Nor Terry Lee either. Are you sure the gauge—”

“I saw it tested with my own eyes,” said Greasy.

“Uh-huh!” said Cannard. “Anything else happen?”

“Not to Bill. Ever since that happened, he damn near takes the plane apart every morning—whichever one of ’em he’s going to test. He found two nuts almost filed through on a strut yesterday, and a pin gone out of one wheel the day before—”

“You mean he’s testing in the full knowledge that somebody is trying to wreck him? And you haven’t told me about it? Why, by the wheels of hades, I ought to fire you on the spot! Sabotage in BCA!”

“Well—there are an awful lot of things that can get wrong with a plane. Bill said just lay low. If we talked about it, why, whoever it was would get scared. Bill said if he caught the guy red-handed, then he could maybe trace back and find out who it was that short-circuited the de-icers on the L97 and so prove to Kip Lee that he didn’t do it because he thought she did things to his pressure gauge—”

“Oh! So we got romance in our business! So agents are trying to sabotage us and we can’t keep an eye out because it might stop one of Cupid’s arrows! Dispatcher! Bring that crazy whizzlewoof of a pilot down here and damned fast!”

Bill, radioed down and flagged down, finally did come down. And when he had eased his long body down the wing to concrete, he looked at Cannard and then Greasy and knew what was going on.

“Just had to talk, didn’t you?” drawled Bill.

“Aw, he wanted to know why you was acting so crazy up there and so I told him. There ain’t no harm in it. We won’t catch the guy ourselves. Honest-to-Pete, Bill, I’m so stiff from sleeping in those 41s that I feel like I’d been eatin’ plaster of Paris.”

“My old pal Greasy!” said Bill, lighting a smoke and leaning against the 41.

“I ought to fire you both!” said Cannard. “Now give me all the details. Why, this afternoon, this very afternoon, the officers are coming out here to make the final comparisons between the two planes, and if that thing was to crash right in front of them they’d give Lee the contract so quick it’d scorch the paper! That ship you are flying seems to be holding together, but I’m going to have it checked part by part, bolt by bolt, rivet by rivet—”

“And rev by rev,” said Bill. “But I’ve already checked it. You think I’d risk my neck in something I hadn’t? That plane is all right, and it so happens that I’ll drill the first gent that touches so much as one wire on it.”

“Not even a refueling crew?”

“I’ll do the refueling—and I’ll do it out of sealed cans,” drawled Bill.

“Why, this is a helluva note! You won’t even trust my own workmen, and yet you won’t tell me—”

“You open up about this and get the FBI crawling all over here and scare that gent away,” said Bill, “and I’ll feed you to the first prop I see!”

“But why—?”

“Because that’s the way it is, that’s all.”

“Listen, Bill Trevillian! Just because you and Kip Lee have to get into a scrap about de-icers is no reason you can tell me how to run my own plant! I’m calling the FBI—right now, if not sooner!”

Cannard went away from there and Bill looked sleepily at Greasy. “Just Walter Winchell himself, aren’t you?”

“Well,” said Greasy, shifting uncomfortably, “I gotta think about your neck if you won’t. Besides, we’ve got one FBI man here all the time, so what difference does another half-dozen make?”

“Cannard is a smart guy,” said Bill. “He’ll howl and rave about this sabotage until the roof comes off, and those French and British officers will just take it as an advance alibi in case BCA 41 falls apart. And if it does fall apart, then they’ll know it was an alibi. I shoulda told Cannard that.”

“You shoulda done a lot of things,” said Greasy, “including stayin’ away from Lee Aircraft that day.”

“Greasy, just for that you can go get me a ham sandwich and a Coke. I gotta fortify myself against the invasion of Uncle Sam’s bloodhounds.”

Greasy was glad to oblige and went across the tarmac like a duck trying to get off the water. Bill stood and communed with his soul, idly snapping and unsnapping his goggles from his helmet.

A nondescript piece of humanity in overalls of the kind one takes for granted slouched up. “Telephone for you, Mr. Trevillian.”

“Huh? Any idea who from?”

“Sounded like a lady, Mr. Trevillian. Long distance.”

“Long—gosh!” And Bill went away from there in a rush. He picked up the down receiver of the hangar phone and told the mouthpiece hello, but the operator parroted, “Number, please.”

“I had a call on this wire,” said Bill.

“Sorry. The party must have hung up.”

“Get me Calver. Get me Lee Aircraft in Calver!”

“Just a moment, please.”

When the call got through to Lee Aircraft, Bill excitedly asked for Kip and waited with eagerness.

“Hello,” said Kip.

“Hello. Look, this is Bill Trevillian. Did you call me just now?”

“Call you?” she said with scorn. “I should say not!” But she didn’t hang up as swiftly as her voice would seem to indicate.

“Somebody said I had a call from a lady, long distance, and gee, I was hoping—”

“Probably somebody you jilted, Casanova!”

“No, look! You’re coming over here this afternoon to test beside BCA 41. Look, I feel lousy about having to fly the ship that may take the contract—”

“Ha! So you’re already grabbing for it, are you? So you’re all set, are you? There’s two planes in that exhibition, Bill Trevillian. And don’t forget it.”

“I didn’t mean—”

“Tell it to whoever phoned you!” And she hung up.

Bill frowned in thought and reluctantly put the receiver back. When he was again beside his plane, the mech was nowhere to be seen and he couldn’t remember which one it had been. There was no one else in sight and so he sat on the wing and waited for his sandwich and Coke.

A few minutes later Cannard came steaming up with a crew in tow.

“Now,” he said energetically, “we’re going to go over this ship bolt by bolt, rivet by rivet—”

“Yeah?” said Bill. “And have one of those monkeys pull out a cotter key someplace? Nope. This thing flies as is.”

“Now, Bill—”

“That’s the way it’s got to be or I quit on the spot!”

Cannard studied him and finally decided that he meant it. He wandered away, dispersing the crew, leaving Bill in grim possession of the lists.

At two o’clock that afternoon the L97 landed at the BCA port and was immediately mobbed by the junior officers. Kip Lee, once more all in white, smiled sweetly upon all of them as she walked toward the stand from which the final contest would be observed. The gallant French would gladly have let her make her way across their bowed heads, and the pink-cheeked subalterns forgot all about the ladies who sighed for them in England. Only once did Kip’s smile leave her and that was when she saw Bill. She passed by him and he was right royally snubbed.

Cannard and Terry Lee were waiting at the foot of the steps with a British colonel, and when the two pilots stood before them, the colonel said, “This is the last proof we must have, you know. We are already quite pleased with the performance of both these American planes. But the question which we must prove is whether one can outmaneuver the other. The camera guns which have been installed upon your wings and mounted in the after pits are connected to the Bowden trips in your cockpits and aligned with your ring sights. Of course the chap who gets the most hits is not necessarily flying the best plane, but I think we can tell which one is top hole by the results. Now, are there any questions?”

“Yes,” said Kip.

“Very well. What is the question?”

“Why can’t we use live ammunition?”

The colonel was quite puzzled, but the mechanics and engineers about, who were in the know, guffawed, puzzling the colonel even further.

Kip turned on her heel and walked to her plane. The junior officers put her into her parachute and then lifted her up. An English boy, swaggering with the honor, climbed into the L97’s gunner’s pit and settled his helmet with a flourish, scowling the while at the BCA 41.

Greasy helped Bill up and then climbed up himself, hauling a filthy helmet down over his ears. Greasy took a fresh chaw and gazed contemptuously at the English lad.

“May the best ship win!” said the colonel, above the mutter of engines.

Kip glowered down the line at the BCA 41 and then shot the throttle forward to send the big pursuit leaping straight out across the field. She was paying no attention to either wind or runway, taking the air in so short a distance that she seemed to need no run at all. She snapped the wing slots closed as soon as she was a hundred feet from the earth and the effect was that of spurs into the flanks of a bronc. Very swiftly she trimmed with the tabs to stabilize for the weight of the young English gunner, and then, climbing in a wide turn, looked back to find that Bill had followed almost upon her tail.

“Showoff!” she growled. And immediately banked the other way to corkscrew skyward and away from him with such speed that between tick-ticks of the heart five miles separated them.

Bill was also climbing, keeping her in sight. The way she had glared at him and then snubbed him had burned like hot iron into his emotions and he was in a state of mind to put her in her place, Terry Lee or no Terry Lee. Snub him, accuse him of sabotage, refuse to see him, laugh at him—! Arrrrr! Wait until he got the camera on her!

Greasy peered speculatively at the black plane and spat indifferently into the slipstream aft. He leaned upon the camera gun and sent an unheard song of considerable bawdy content outward with the racket of the two engines. Some of Bill’s mood entered into him. Far below he could see the bright spots of color which marked the stand, but as these were already fading to a dot he soon lost interest. Kip’s black ship was clawing for height, determined to get the better of the first contact through additional altitude.