Chapter Three

Have Difficult Conversations

“Speak when you are angry and you will make the best speech you will ever regret.”

—Ambrose Bierce

Interpersonal conflicts are the most common source of stress that I see in workplaces. It’s tough working with people who have different attitudes, approaches, and behaviors than we do. Often, we feel frustrated, misunderstood, or angry. Most of us just want to avoid having a difficult conversation, but the longer we avoid it, the more complicated having the discussion becomes.

When we have the tools and confidence to have a difficult conversation, we can have it sooner which will ensure the discussion goes far more smoothly than if we let things fester for days, weeks, or even months and then try to deal with the situation. This chapter is full of tools to help you prepare for and have all those conversations you’ve been avoiding

.

To prepare for a difficult conversation, it’s a good idea to identify the source of your stress, understand how you are contributing to the situation, and consider the possible actions you can take.

You might not think you are doing anything to contribute to the situation, but I guarantee that you are. Even if all you are doing is being silent about your frustrations and not addressing the problem, you are contributing to the situation. To help you think through your part in the dynamics, consider the personal responsibility questions again:

Personal Responsibility Questions

1. Why is this situation so upsetting for me?

This question helps you identify what you’re feeling and why.

2. How did I contribute to this situation?

This question helps you identify how your behaviors might have contributed to the stressful situation and begin to change them.

3. What can I learn from this situation?

When you focus on learning from the situation, you can concentrate on growth rather than stressing out.

4. What can I do about this situation?

This question helps you focus on specific solutions and strategies.

5. What can I do differently next time?

This step helps you identify the specific behavior you need to alter to get different results in the future.

When we focus on ourselves and take personal responsibility for our role in a difficult dynamic, our intention in a conversation switches from fixing or blaming the other person to improving our interactions.

Preparing For the Conversation

To prepare for a difficult conversation, we want to think about what our purpose in having the conversation is. When we’re focused on the outcome of the conversation, we can prepare what we want to say and even practice having the conversation (you can role-play with a trusted

friend, coach, or your mirror) with our intentions in mind. I encourage you to let go of your judgments and assumptions about the person you’ll be talking to—it’s a difficult conversation because of something that they have done or said, and the discussion becomes more difficult when we layer our own judgements on top of their actions. When we can go into difficult conversations with an open mind and listen to the other person with curiosity rather than judgment, we will usually get a far better outcome.

Another strategy is to start the conversation by taking personal responsibility for our behavior. When we can identify how we have contributed to the dynamic, often we will set the tone for the other person to reflect on their behavior, and the conversation is a lot less bumpy than if we go into it with guns blazing.

It’s also really important for us to manage our feelings before we go into the conversation. I’ve coached so many people who are either nervous or angry or frightened going into a difficult conversation. Rather than taking those feelings into the conversation with you, explore and express them before you enter the conversation. You can write out everything you’re feeling or tell the mirror how upset you are or talk through your feelings with a coach or a close friend. When we’ve addressed our feelings about the issue, we can enter the conversation from a much calmer place.

Listen First

If we enter a conversation with the intention to listen deeply to the other person to understand where they are coming from, we can have a much different conversation than if we go into it prepared to make our points and prove that we are right. It can be hard to slow down enough to listen, but when you bring up a concern and then listen to the other person’s perspective before trying to get your own point across, the conversation goes way better.

We also need to schedule enough time to have the difficult conversation. Many people are so busy that they try to have important and complicated conversations in a short time frame, which ultimately

results in people feeling rushed and not listening well. This can lead to misunderstanding, miscommunication, and sometimes conflict.

If listening is a challenge for you, here are a few reminders of how to listen well:

- Remove all distractions: put your phone away, turn off computer notifications and turn away from your computer.

- Go for a walk or plan the discussion in a neutral, distraction-free environment.

- Schedule enough time for the conversation so you aren’t rushed or thinking about your next meeting.

- Let go of your stories and judgments about the person and the situation and listen with curiosity and an open mind.

- Paraphrase what you’ve heard to ensure you’ve understood correctly.

- Acknowledge the feelings the other person is expressing.

- Ask questions to keep yourself focused on the conversation and ensure you understand the speaker.

- Enter the conversation with the intent to listen to the other person with the goal of understanding their perspective (rather than listening with the intent to prove your point).

When we can approach a difficult conversation with an open mind and the intent to listen to the other person, it will often transform into a much easier conversation than we envisioned.

Your Triggers

We all have our own histories and unique experiences that make us react more strongly to some situations or individuals than other people might. These are often called triggers

as they trigger automatic reactions in us.

For example, years ago, I worked for a man who was a very distant and distracted manager. One of my coworkers absolutely loved working for him as she liked the autonomy she had. While I also appreciate freedom and autonomy, there was something about this manager’s

style that I found upsetting. I often felt dismissed and hurt after our interactions. After one of our more difficult meetings, during which he was confused about what projects I was working on—even though we’d discussed the projects in detail a few days earlier—I asked myself the first personal responsibility question, “Why is this so upsetting for me?”

As I sat with the question, I realized that I felt similar to the way I’d felt as a child when I’d told my father about things that were really important to me, and he didn’t really pay attention so he promptly forgot. My father was very distracted while I was growing up, and this manager had similar behaviors. I reacted to his behavior quite strongly because it brought up old feelings. Because I’d taken some time to think about what was so upsetting for me in our interactions, I realized this was my issue and was able to deal with it myself rather than have it interfere with our working relationship.

When I went into meetings with my manager, I expected him to be unprepared and distracted, and I didn’t take his lack of attention to my work personally. I knew he was really busy, and he trusted me to get the work done. Changing my perspective made our working relationship far less stressful.

Asking the first personal responsibility question is a good way to help you identify if you might be feeling triggered and bringing some of your own interpretations or past issues to the interaction.

Is there someone at work who you have a very strong reaction to?

Why is that person so upsetting for you?

Are there ways that you need to adapt your approach to working with this person

?

Managing Your Emotions In the Conversation

When we’re in the midst of a difficult conversation, it can be hard to remain calm, but staying emotionally steady is going to create the best outcome in the conversation. Here are a few tips to help you bring yourself back to a place of calm if you find yourself getting emotional. We will discuss more general strategies in the “Manage Your Mental and Emotional State” chapter, but these ones are useful for calming yourself down in the moment:

- Breathe deeply, take three deep breaths—this is magic, just try it now and see how much more relaxed you feel.

- Remind yourself that you have no idea what the other person is going through.

- Don’t take the other person’s behavior personally.

- Identify what you’re feeling—simply labeling the emotion in your mind will reduce the emotion.

- Put things in perspective—How much does this really matter? How much will it matter next week? Next month? Next year?

- Notice the physical signs of escalating feelings and change your posture to a more relaxed posture (unclench your fists, relax your shoulders, unclench your jaw, etc.).

- If necessary, leave the situation temporarily to get grounded and come back when you are calmer.

- Focus on what you can control: your response. If you get emotional, the other person won’t remember what you said, only that you were angry, sad or upset, so your message will be lost.

- Ask questions or discuss facts. This moves you from the emotional side of the brain to the rational side of your brain

.

Talk to Coworkers, Not About Them

An unhealthy workplace behavior that I see frequently is when one person has an issue with another person, but they don’t talk to them, they talk about them.

If you do that, stop. It doesn’t resolve the situation; it actually makes the situation worse and contributes to a culture of gossip and negativity. If you’re really frustrated and need a listening ear, talk to someone outside of work who can keep the conversation confidential. If it’s a situation that has workplace implications and you need to involve your manager, your union rep, or HR, do so after you have thought through the situation and you are clear on your part in it and the kind of support you need.

Many people, consciously or unconsciously, choose endless, sleepless nights over having a difficult conversation. They talk to everyone in the world about the problem except the person they have the problem with. Please stop avoiding tough conversations. Instead, prepare for them.

Focus On Preserving the Relationship

Dealing with interpersonal conflict requires a genuine desire to resolve the situation and find a good outcome for both of you.

The point of conflict is not to determine who is right or wrong (a trap I sometimes fall into) but to find a way to stay in relationship with each other.

If we can approach a difficult conversation with the goal of staying in relationship with the other person and discussing our perceptions as perceptions rather than facts, the conversation will go more smoothly. Both people need to work at it, and, of course, you can only do your part. But you’ll often find that if you do your best to make it work, the other person will follow your lead

.

Trust me, I know that there are people out there who are almost impossible to work with. They seem to delight in making life difficult for others. I’m sorry if you have to work with someone like this—it’s awful. I’ve lived it and it nearly broke me. I’d come home every day feeling frustrated and stressed out and dreading having to work with this colleague the next day. Then I figured out how to have difficult conversations and deal with my challenges in a healthy and professional way. Believe me, that person was never my favorite person in the world, but dealing with them became much easier after I had the courage to have a difficult conversation. Even just having the conversation was enough to change the dynamic between us, and I felt more relaxed.

Think about some of those people who cause you a lot of stress. Wouldn’t it be nice to reduce their impact on you? There are two ways to do this. You can choose to not take their behavior personally and ignore it, shrug your shoulders, and think “Oh, that’s just Amy, doing her thing, nothing to do with me.” This is the approach to take if the behavior is designed to get a reaction from you or if it’s really just not worth getting that upset about. When you stop reacting and taking the behavior personally, your stress levels will decrease.

The other response is to address the behavior. This is the approach to take if you want to let the other person know how they are impacting you. Your goal in this conversation is to make changes in how the two of you interact. A common progression is that people try the first strategy of letting the behavior roll off their back; then if they realize they can’t let the behavior go, they choose to have a conversation to give the other person some feedback.

Reframing Feedback

One way we can become more comfortable offering feedback is to reframe it. We often perceive a feedback conversation as a threat, something that will cause us pain. Usually when thinking about giving someone feedback, we feel a pit in our stomachs and dread coursing through our veins. We’re worried that we might upset the other person and possibly damage our relationship with them or make things even worse

.

What if we reframed the whole idea of feedback? When we give someone feedback, it’s because we want to improve our relationship—otherwise we wouldn’t bother. When we can stop being fearful of hurting the other person and can recognize that our true intent is to help them, feedback conversations feel less frightening.

When you tell someone that their fly is undone, they’re genuinely grateful as you’ve saved them from embarrassment! A coworker might feel the same level of gratitude when you let them know about a workplace behavior they’ve been engaging in that’s having a negative impact.

We can also reframe a feedback conversation to see the potential reward of taking our power back by dealing with our stress.

Timing and the Difficult Conversation

When preparing to offer feedback or to have a difficult conversation, it’s important to consider the timing. In an ideal situation, you’ll want to offer feedback as soon after the incident as possible. It’s possible to give feedback within a few minutes or an hour of an interaction, but only if you feel calm enough to have the conversation respectfully and if you sense that the person is able to be receptive and listen to the feedback.

If you need some time to recover or prepare and you sense the other person might have the same need, I recommend the twenty-four- to forty-eight-hour rule: give yourself a day or two to process the events, consider your approach, and get yourself into the right mind frame to address the issue. Don’t leave it any longer than that because the associated stress and worry just builds up and the situation becomes harder to deal with. Ask the person when a good time to talk would be and approach the conversation with a genuine desire to resolve the situation.

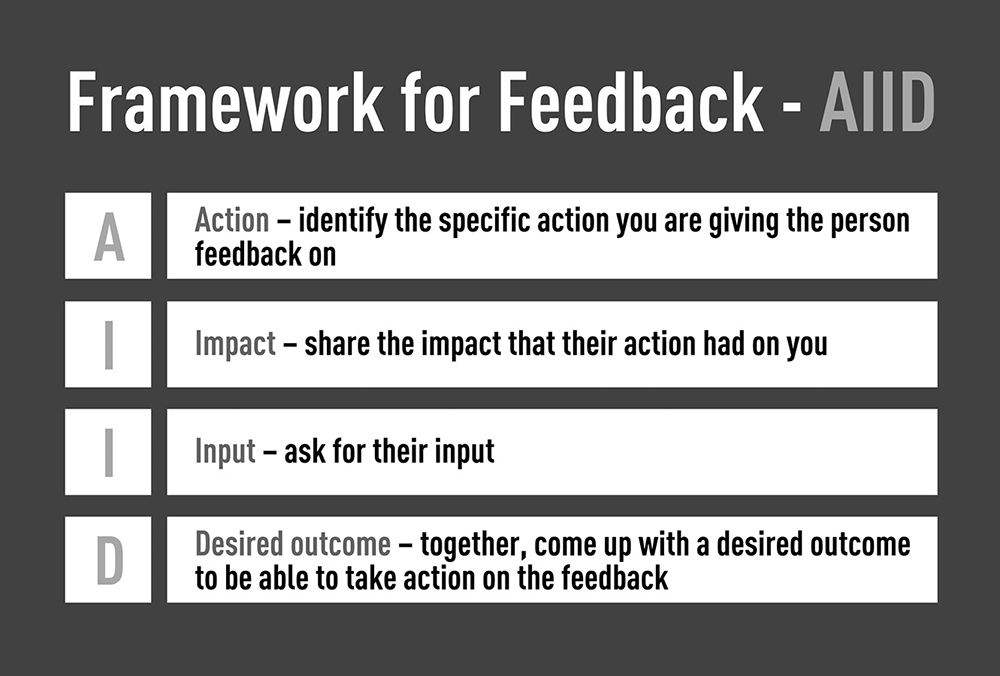

The AIID Model

We can also have conflict and challenges with people that we enjoy working with, and we need tools to resolve these challenges as well.

If you decide to have a feedback conversation, either with a difficult person or your work spouse, I encourage you to use the AIID feedback model. I’ve taught this approach to thousands of people, and I’ve seen it dramatically change their relationships for the better.

A

stands for Action.

The first step of the AIID feedback model is to identify the specific action that is problematic. Here, you have to be as specific as possible—being vague is tempting because you may feel nervous, but being specific is stronger and more clear. Think about the last time you got frustrated with someone at work—what did they do specifically?

For example, if one of your coworkers or staff members is always late, you don’t want to be vague and say, “You’re always late these days.” That broad and judgmental statement is likely to make the person feel defensive. “Always” and “never” are words best avoided in any conversation.

Instead, choose a specific action or behavior that has occurred in the recent past (ideally in the past day or two, and no more than one week ago) and describe it as specifically as possible. You could say, “For the last three days, you have come in fifteen minutes late . . .” or, “I noticed you came in twenty minutes late four times last week; I’m just

wondering if everything is okay?” This specific feedback is much easier to receive. I’ve used a very simple example here, but if you think back to George, he used this model to give his manager feedback on the specific ways he was feeling micromanaged. You can use this model for any kind of feedback, just remember to be as specific as possible when describing the Action

.

I

stands for Impact.

After you have clearly stated the Action

, you need to share with the person the Impact

that their action had on you. This is key. So many people make significant changes to their behavior after they became aware of its impact.

In this situation, you could simply say, “We can’t get started until you are here, so we start our days late.” Or, “When I’m waiting for you to arrive, I feel frustrated because I’ve worked hard to arrive on time.” This approach helps the person understand how you feel in response to their actions, and we can usually connect with one another’s feelings.

Being aware of our tone in these conversations is really important. We want to have an open and curious tone. That’s why it’s a good idea to address issues as soon as they arise.

We usually feel more frustrated as the situation goes on, but if we speak to someone about a challenge as soon as it arises, it’s easier to maintain curiosity and open-mindedness.

Understanding our impact on others can generate insights that will propel us to take action and change. In one of my leadership classes, I give students an assignment to go and ask five people for feedback. One of my students had a profound realization when people told him that when he was sarcastic it made them shut down and they did not want to bring issues to him. When they shared how he made them feel (anxious, worried about his response), he had a much better understanding of his impact.

He had always known that he was sarcastic and until then he had prided himself on it, thinking it made him funny and approachable. When he saw that he was having a totally different impact than the one he’d intended, he cut out all sarcasm because he wanted to be approachable

.

The second

I

stands for Input.

This is the step we most often forget, but it’s so important. Without asking the other person for their Input

, we haven’t really communicated, we’ve just told them about the Action

and the Impact

it’s had on us.

After you’ve shared your feedback, it’s time to stop talking and listen.

At this stage, you ask the other person for their Input

. There are two questions you can ask. The first question is something along the lines of “What’s up?” or “What’s going on?” Again, we need to be so aware of keeping our tone light and curious in this discussion. When we ask the person what’s going on for them, and truly listen, we can get to the root of the problem and work towards solving it. The next question is: “What do you think we can do about it?”

The most important thing to do now is to listen to the other person.

Keep in mind that they might be feeling hurt or defensive, so it could be difficult for them to engage in the conversation.

Give the other person the opportunity to share their perspective and ideas. After you have listened to them, you can share your own ideas. Often people will come up with far better solutions than you will—and most importantly, they will be committed to them because they suggested them. If I were to suggest to a staff member or coworker who was always late that they just set their alarm twenty minutes earlier, how do you think they would respond? Most of us know how best to solve our own problems, we just need someone to listen and talk things through with us.

D

stands for Desired Outcome.

When having a feedback conversation, it’s important to make sure both of you are clear on the desired outcome based on the feedback given. It’s valuable to come up with this outcome together so that you are both invested and it doesn’t feel like one person is telling the other what to do (yes, this works well even when you are a manager speaking to an employee). In the example of the coworker being late, the Desired Outcome

seems fairly obvious: that they arrive at work on time. But your discussion might land you somewhere totally different. For instance, you may realize that due to

their circumstances, they need to start and finish their work day half an hour later.

Go into the conversation with a curious, open mind, and you’ll be surprised at where it can lead.

Usually the Desired Outcome

will grow organically from having listened well to one another.

After you have both agreed on the Desired Outcome

, set a time to follow up and see how things are going. If things are still off track, you can discuss other solutions. If things are on track, you can focus on what’s working and build on that.

Give Feedback Frequently

Whenever you have a challenge with someone, give them constructive feedback. The more comfortable and practiced you become, the easier it is to do. Often, when we let someone know about the impact of their behavior on us, that is enough for them to make a change.

Other times, they won’t change no matter what we say or do. But if that is the case, you’ve done your best; you have taken action to reduce your stress. If you’ve given someone feedback and things haven’t changed, you can simply turn your attention to managing how you respond because that’s the only thing you can control in the situation.

Who do you need to have a feedback conversation with?

Who have you been avoiding sharing constructive feedback with?

Take a moment right now to think about how you would frame the specific action and impact to help you prepare for the feedback conversation. Here’s a basic example

:

Specific action: When you interrupted me three times during that conversation.

Impact: I felt frustrated and I didn’t feel like my opinion mattered.

After you’ve identified the action and impact you want to discuss, set yourself a deadline within the next few days to go and have the feedback conversation you’ve been avoiding. I know it can be hard to work ourselves up to the conversation, but the sooner you do it, the less stressed you will feel. In the future, do your best to stop avoiding these types of conversations—the next time something feedback worthy happens, push yourself to give feedback within one to two days.

Remember to approach the conversation with an open mind and listen to the other person’s perspective. I regularly give an assignment to students where they have to have feedback conversations they’ve been avoiding, and they always return to class feeling relieved that they had the conversation. Almost all of them find that the conversation goes far better than they anticipated.

The more frequently we give feedback, the more comfortable we become having those difficult conversations.

How Feedback Can Help You

I know you’re not a difficult person at all, neither am I. We are perfect, and all those people we work with are difficult. I get it. But on the rare occasion, it’s just possible that we might also be a teensy bit difficult.

If you can find the courage to ask your coworkers and your manager for feedback, you might learn a few things that will help you grow. In addition to improving your relationships, asking for feedback has plenty of career benefits. As Sheila Heen and Douglas Stone share in their book

Thanks for the Feedback

, research has found that “feedback-seeking behavior has been linked to higher job satisfaction, greater creativity on the job, faster adaptation in a new organization or role, and lower turnover. And seeking out negative feedback is associated with higher performance ratings.”

1

Asking for feedback might be really good for us, but it’s kind of terrifying. The first time I asked someone for feedback, I felt like I was

going to throw up. The second time, I felt slightly less nauseous. Now, I just get a few butterflies. If you can muster up the courage to do it, you’ll have my utmost respect.

We all want to be loved and accepted just as we are. Feedback hurts because it’s the opposite of that. But if we can focus on our desire to learn and grow rather than our need to be accepted, we can take feedback in much more easily.

Just like when we are giving feedback, we want to be as specific as possible when asking for feedback. Maybe you want to improve your communication or presentation skills, or you would really like feedback on how to be a better listener.

Instead of saying, “Can you give me some feedback?” say, “Can you give me some feedback on how I can be a better listener?”

When someone is giving you feedback and you feel tempted to punch them in the face and then explain all the reasons they’re wrong, know that your reaction is totally natural. We’re hardwired to defend against feedback. Instead of a throat punch, smile and thank the person for sharing their feedback as you know it takes courage. Then see what you can learn from what they have offered you.

Likewise, when giving feedback, be prepared for a defensive reaction. When it happens, acknowledge that it’s hard to hear difficult feedback, and express that you appreciate that the person has listened to your concerns.

Who are three people you could ask for feedback?

What specific feedback questions will you ask them?

I’d encourage you to choose at least one or two people from your personal life as well as your workplace. The first time I asked for feedback on my listening skills, everyone I asked thought I was a very attentive and focused listener except . . . wait for it . . . my husband. He was right: I was using up all my attentive listening at work. I was so grateful I’d

asked (and listened openly to his response), and I’m a much better listener at home now because I really want my family to feel listened to and valued.

Give the people you’ve selected a heads up, so they have time to think about your questions. When asking for feedback, we want to give the other person time to prepare so that they can offer us useful feedback.

We also want to have one-on-one conversations. One of my clients complained to me, “Every week in our staff meeting, I ask my staff for feedback, and they just smile and say everything is good.”

I laughed and explained, “That’s because they are nice people. They don’t want to say anything negative to you in front of others.”

Her eyes opened wide. “You’re so right. That would have been really awkward if they’d been critical of me in front of the team.”

When she scheduled some one-on-one meetings where she asked for specific feedback, she was able to get meaningful feedback that helped her adjust her management style.

If you’ve decided to ask someone for feedback, you might want to send them an e-mail and let them know you’d love some feedback. Include your specific feedback questions and ask them to meet with you to discuss their responses.

Here is an example e-mail that I often have my clients send to their staff when they are seeking feedback on their management style.

Hi, John. I’d really value your feedback on how I’m managing you. I have a few questions that I’d love you to consider before we meet:

-

As your manager, what would you like me to do more of?

-

As your manager, what would you like me to do less of?

-

As your manager, what would you like me to keep doing?

And, of course, if there is anything else that comes to mind, I’d love to learn from your feedback. I’m genuinely interested in hearing how I can support you

as your manager, so please be as open and honest as possible.

Please don’t e-mail your responses. I’d prefer to meet in person to discuss. Can we meet next week?

You could easily take this sample and insert your own questions into it to help you open up the feedback conversation. Asking for feedback takes courage, but when you have those conversations, you’ll learn a lot and build more trust in your relationships. There are two keys to building trust through feedback conversations: don’t get defensive and act on the feedback you’ve received.

To Give Feedback or Not

When I’m assessing whether I should give another person difficult feedback, I consider how much energy I’m putting into the issue:

- Is it keeping me awake at night?

- Is it impacting our working relationship?

- Is it impacting the work we are doing?

- Am I talking to a coach or trusted friend about it?

- Do I complain about this person to my husband on a regular basis?

If the answer to any of these questions is yes, I always choose to give feedback. Giving feedback is an action I can take to resolve the situation. I give feedback, then let go of the outcome. I hope that the other person will change, but I can’t control that.

We encounter all kinds of challenging situations and personalities at work and in our lives. Some people are outright jerks, others are just going through a difficult time themselves. Some people are genuinely unaware that their behavior is causing any problems. When we give those people feedback, we are actually doing them a favor by letting them know about the impact of their actions.

If we want to reduce our stress, we have to figure out ways to reduce the impact that difficult people have on us. We can’t control other people, so we have to focus on what we can control: ourselves and our responses.

The way we interact with others has a huge impact on our productivity. We’ll talk more about this in

Chapter Eleven

, but for now, think about what you can do to ensure you have strong working relationships. The better your relationships are, the more effectively you’ll be able to work together.

The Value of Positive Feedback

On the note of building positive relationships, the AIID feedback model can also be used for providing positive feedback. We’re often so busy that we forget to make the time to point out what we appreciate about one another.

I encourage you to give positive feedback as often as possible. When you notice things going well or feel appreciation for someone, acknowledge it by giving them positive feedback. Taking two minutes to share a specific action someone took and the good impact it had on you will go miles towards building strong relationships, both at home and at work.

It can be a quick conversation, a two-line e-mail, or a thank-you card, depending on the situation. Giving positive feedback doesn’t take much effort, but it can have a powerful impact on our relationships and the people that we work with. Building and maintaining healthy relationships is always preferable to having to fix them.

Please give positive feedback in a separate conversation than when you’re offering constructive feedback.

Our brains are hardwired to remember only the more negative aspects of a conversation, so the positive feedback gets forgotten too easily if it’s delivered at the same time as constructive feedback

.

You don’t want to be the person who offers only critical feedback—you know, the one that people cringe when they see her coming? Even if it’s your natural style to be more critical, think of the ways you could provide positive feedback and the great impacts that could have on your relationships. As a bumper sticker I saw recently said: “Wag more, bark less.”

Giving positive feedback doesn’t just help build our relationships, it also significantly improves productivity. Research conducted by Marcial Losada determined that we need to have a ratio of three positive interactions for every negative one in order to make a corporate team successful.

2

Interestingly, John Gottman, researcher and marriage expert, found that to keep a healthy marriage, the ratio was five positive interactions for every negative one.

3

The research is in: be nice to your coworkers and even nicer to your spouse.

Losada used the three-to-one formula with a global mining company that was losing money. He told team leaders they had to give more positive feedback and encourage more positive interactions. And do you know what happened? The company went from losing money to making money. They improved their performance by over 40 percent.

4

I love this research because it shows the very tangible result that we can get from sharing positive feedback and engaging in positive interactions.

Providing positive feedback can have incredible impacts on our team’s productivity, on our relationships, and on our work. It takes no time at all, and you can make someone’s day by sharing your positive feedback with them.

This doesn’t apply just to work. Think about all the people you encounter in your day: your friends, family members, the server at the restaurant. Sharing positive feedback with others builds stronger relationships and connections, helps improve productivity, and increases happiness.

Who can you share some positive feedback with today

?

Take a moment right now to think about how you would frame the specific action and impact to help you prepare for the feedback conversation. Here’s a simple example:

Specific action: When you stayed late to help me work on that project.

Impact: I felt really supported and even more motivated to get the work done.

Take some time to have a positive feedback conversation in the next week and notice the impact it has.

Conclusion

Nobody loves having a difficult conversation. But the sooner you have the conversation, the easier it will be. You’ve now got plenty of tools to enable you to have a difficult conversation, remember to listen well, maintain your calm, reframe feedback conversations, find ways to reduce the person’s impact on you, use the AIID feedback model to guide you through a tough conversation, and focus on the one and only thing you can control in these situations: your actions and responses.

The more often you have difficult conversations and deliver difficult feedback, the easier it will get.

And remember, we’re all difficult at times. Maybe asking for some feedback and reflecting on your own behavior might help you be a little less difficult for some of the people you work (or live) with.