INITIAL STRATEGY

Sources for the Raid

As the events of 1609 are so little known outside Japan, there are few written accounts in English apart from short passages in George H. Kerr’s Okinawa: The History of an Island People and A. L. Sadler’s The Maker of Modern Japan. The literature about Satsuma’s occupation of Ry ky

ky is more comprehensive, but no book or article contains more than a brief mention of the war through which it all began, and only one academic article on the subject has ever been published in any European language. This is ‘Die Ry

is more comprehensive, but no book or article contains more than a brief mention of the war through which it all began, and only one academic article on the subject has ever been published in any European language. This is ‘Die Ry ky

ky Expedition Unter Shimazu Iehisa’ by R. Binkenstein, which was published in an early issue of Monumenta Nipponica in 1941. Binkenstein, however, made no use of the primary sources referred to below. His sources were largely confined to gunkimono style accounts of the campaign, where the exploits of the brave Shimazu samurai were blatantly exaggerated for the benefit of their descendants, similar to the famous medieval gunkimono such as Heike Monogatari and Taiheiki. Recognising these limitations, Binkenstein included little discussion of the invasion itself and concentrated instead on the events leading up to it.

Expedition Unter Shimazu Iehisa’ by R. Binkenstein, which was published in an early issue of Monumenta Nipponica in 1941. Binkenstein, however, made no use of the primary sources referred to below. His sources were largely confined to gunkimono style accounts of the campaign, where the exploits of the brave Shimazu samurai were blatantly exaggerated for the benefit of their descendants, similar to the famous medieval gunkimono such as Heike Monogatari and Taiheiki. Recognising these limitations, Binkenstein included little discussion of the invasion itself and concentrated instead on the events leading up to it.

The authentic written sources for the Okinawa expedition are few in number and very obscure. They are however very reliable, and may be divided into three categories. The most important are three eyewitness accounts of the events. The first, from the Ry ky

ky an perspective, is Kyan Nikki, which was compiled in about 1627 by the priest Kyan Ueekata (Kian Oyakata) who, originally from Sakai in Izumi province, went to Okinawa in 1600 and became a close associate of King Sh

an perspective, is Kyan Nikki, which was compiled in about 1627 by the priest Kyan Ueekata (Kian Oyakata) who, originally from Sakai in Izumi province, went to Okinawa in 1600 and became a close associate of King Sh Nei. In Kyan Nikki, almost the entire invasion is described in detail by a man who had been involved in the earlier negotiations to avoid the war, saw it unfold on Okinawa and then accompanied his king into exile.

Nei. In Kyan Nikki, almost the entire invasion is described in detail by a man who had been involved in the earlier negotiations to avoid the war, saw it unfold on Okinawa and then accompanied his king into exile.

The other two eyewitness sources are from the Satsuma standpoint and are included in a published collection of historical documents from Kagoshima prefecture. One is entitled Ry ky

ky Tokai Nichi Ki and is the diary of Ichiki Magobe’e Iemoto, who served in the invading Shimazu army in the Takayama sh

Tokai Nichi Ki and is the diary of Ichiki Magobe’e Iemoto, who served in the invading Shimazu army in the Takayama sh (Takayama Company – named after the place in which the unit was stationed). Ichiki was involved in the section of the army that took the overland route after landing on Okinawa. The other account, Ry

(Takayama Company – named after the place in which the unit was stationed). Ichiki was involved in the section of the army that took the overland route after landing on Okinawa. The other account, Ry ky

ky Gunki, was written by an eyewitness who sailed with the fleet as it attempted to force an entry into Naha Harbour. The author is believed to have been a funegashira (ship’s captain) based on the Tokara Islands. Only seven out of the twelve Tokara Islands are inhabited, hence the expression Shichit

Gunki, was written by an eyewitness who sailed with the fleet as it attempted to force an entry into Naha Harbour. The author is believed to have been a funegashira (ship’s captain) based on the Tokara Islands. Only seven out of the twelve Tokara Islands are inhabited, hence the expression Shichit (Seven Islands) that is used in his account. Despite its title, Ry

(Seven Islands) that is used in his account. Despite its title, Ry ky

ky Gunki is not a romantic gunkimono but a sober and often brutal account of the invasion in which no attempt is made to disguise the various setbacks experienced by the Satsuma army. Using these three primary sources, it is possible to recreate a day-to-day account of the operation from three different locations and from two different perspectives.

Gunki is not a romantic gunkimono but a sober and often brutal account of the invasion in which no attempt is made to disguise the various setbacks experienced by the Satsuma army. Using these three primary sources, it is possible to recreate a day-to-day account of the operation from three different locations and from two different perspectives.

The Shimazu family archives are the second valuable source of authentic written material, containing documents relating to the planning, organisation and execution of the raid, such as muster lists, notes on casualties and official reports.

The third category comprises two gunkimono, the Shimazu Ry ky

ky Gunseiki of 1663 and Satsury

Gunseiki of 1663 and Satsury Gundan, which is an abridgement of the former. Shimazu Ry

Gundan, which is an abridgement of the former. Shimazu Ry ky

ky Gunseiki is a fictionalised account of the conflict in which the Shimazu family of the latter half of the 17th century could read of the exploits of their fathers in the family’s last great expedition. As already mentioned, embellishments and exaggerations are common in gunkimono, particularly with regard to troop numbers, but the most curious aspect of Shimazu Ry

Gunseiki is a fictionalised account of the conflict in which the Shimazu family of the latter half of the 17th century could read of the exploits of their fathers in the family’s last great expedition. As already mentioned, embellishments and exaggerations are common in gunkimono, particularly with regard to troop numbers, but the most curious aspect of Shimazu Ry ky

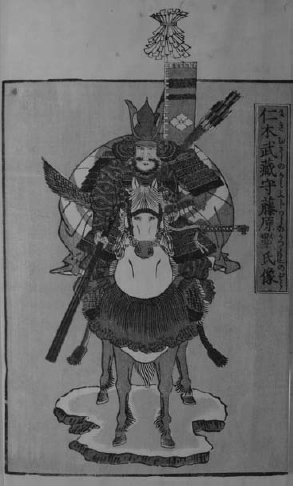

ky Gunseiki is that all the names of the generals who took part and the battles in which they fought have been changed. The actual commanding officer, a samurai general called Kabayama Hisataka, is never mentioned; instead the leadership of the army is credited to the veteran Shimazu retainer Niiro Musashi-no-kami, who did not actually take part in the invasion. At the time of the raid he was already 84 years old, and he died just a year later in 1610. Similarly there is no sense of geography, so the attack on Y

Gunseiki is that all the names of the generals who took part and the battles in which they fought have been changed. The actual commanding officer, a samurai general called Kabayama Hisataka, is never mentioned; instead the leadership of the army is credited to the veteran Shimazu retainer Niiro Musashi-no-kami, who did not actually take part in the invasion. At the time of the raid he was already 84 years old, and he died just a year later in 1610. Similarly there is no sense of geography, so the attack on Y keidan Castle – described as the way in to Ry

keidan Castle – described as the way in to Ry ky

ky – may actually refer to the Shimazu’s initial attack on the fortress of Nakijin, or it may be an entirely fictional episode. Shimazu Ry

– may actually refer to the Shimazu’s initial attack on the fortress of Nakijin, or it may be an entirely fictional episode. Shimazu Ry ky

ky Gunseiki is nonetheless very revealing about the attitudes of the samurai class at that time. According to Shimazu Ry

Gunseiki is nonetheless very revealing about the attitudes of the samurai class at that time. According to Shimazu Ry ky

ky Gunseiki, bullets always ‘fly like rain’ and war cries invariably ‘shake heaven and earth’, while the Shimazu force is sometimes referred to as the ‘Japanese army’ and Japan as ‘the land of the gods’. Despite their many elaborations, the gunkimono may also contain some hints about the way the army was organised. During the early 19th century an illustrated account of the raid was produced. Entitled Ehon Ry

Gunseiki, bullets always ‘fly like rain’ and war cries invariably ‘shake heaven and earth’, while the Shimazu force is sometimes referred to as the ‘Japanese army’ and Japan as ‘the land of the gods’. Despite their many elaborations, the gunkimono may also contain some hints about the way the army was organised. During the early 19th century an illustrated account of the raid was produced. Entitled Ehon Ry ky

ky Gunki (ERG), it contains a narrative based on Shimazu Ry

Gunki (ERG), it contains a narrative based on Shimazu Ry ky

ky Gunseiki.

Gunseiki.

Army Leadership

Shimazu Iehisa, the daimyo of Satsuma, played no part in the actual military operation, although this decision was not based on any lack of soldierly skill. In 1598, he and his father had become the heroes of the battle of Sacheon, and his subsequent rule of Satsuma had shown that he had the necessary qualities of ruthlessness and tenacity to carry out such an audacious operation. The following year, Iehisa’s mansion had become the setting for the murder of Ijuin Tadamune, a man who had once been one of the Shimazu’s most loyal retainers. Tadamune’s personal ambitions and wealth, arising from his service in Korea, had tempted him into setting up a petty kingdom of his own in the Sh nai area, a development which the Shimazu could not tolerate. In 1602, Shimazu Iehisa dramatically quelled the Sh

nai area, a development which the Shimazu could not tolerate. In 1602, Shimazu Iehisa dramatically quelled the Sh nai Rebellion, a revolt led by Tadamune’s son Tadazane, by having Tadazane murdered during a hunting expedition.

nai Rebellion, a revolt led by Tadamune’s son Tadazane, by having Tadazane murdered during a hunting expedition.

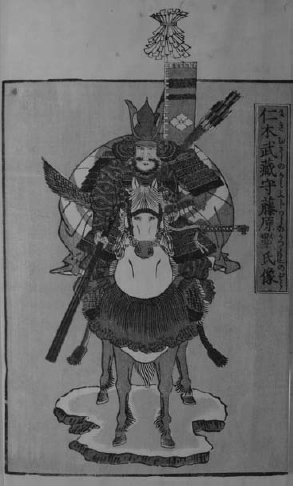

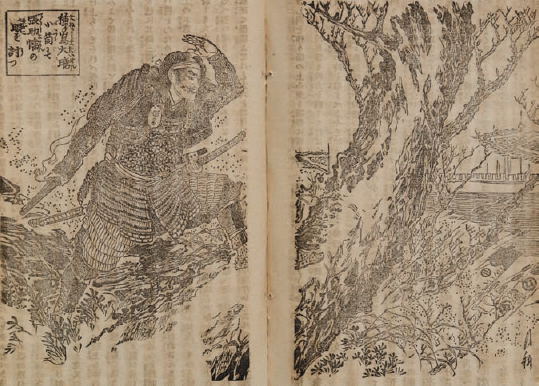

The veteran general of Satsuma, Niiro Musashi-no-kami, is shown here in the frontispiece to Ehon Ry ky

ky Gunki. In the gunkimono accounts of the Okinawa operation he is credited with leading the raid. He actually never left Kagoshima, but the real leader, Kabayama Hisataka, would have looked very similar to this dramatic depiction.

Gunki. In the gunkimono accounts of the Okinawa operation he is credited with leading the raid. He actually never left Kagoshima, but the real leader, Kabayama Hisataka, would have looked very similar to this dramatic depiction.

However, Shimazu Iehisa faced discontent among several senior Shimazu retainers, whose resentment found expression in opposing the overall plan for an expedition against Okinawa, as well as the fine details of its execution. Their concerns over what could be a foolhardy venture served to highlight the fact that the seemingly united Shimazu family was in reality split into three separate factions loyal to the current daimyo and his predecessors. The three groupings were called the Kagoshima-kata, the Kokubu-kata and the Kajiki-kata; they were associated with the castles of Tsurumaru (Kagoshima) commanded personally by Shimazu Iehisa; Shinshiro (Kokubu) under Shimazu Yoshihisa, and Kajiki under Shimazu Yoshihiro. Iehisa’s decision not to lead the army in person may well have taken into account the danger of leaving his fief without its leader, but some of the fiercest opposition to the plans concerned the man that Iehisa had chosen to act in his stead. The leader selected for the invasion was Kabayama Gonza’emonnoj Hisataka, a man whose family would be associated with Ry

Hisataka, a man whose family would be associated with Ry ky

ky for many years to come. His descendant, Kabayama Sukenori, became the first Japanese governor of Formosa (Taiwan) in 1895, but almost nothing is known of the earlier Kabayama. In accounts of the raid he is an almost anonymous figure, even more shadowy than his second-in-command Hirata Tar

for many years to come. His descendant, Kabayama Sukenori, became the first Japanese governor of Formosa (Taiwan) in 1895, but almost nothing is known of the earlier Kabayama. In accounts of the raid he is an almost anonymous figure, even more shadowy than his second-in-command Hirata Tar za’emonnoj

za’emonnoj Masamune. The retainer band opposed Hisataka’s appointment over Masamune, stressing the fact that Kabayama Hisataka was the younger of the two men, but the dispute was eventually resolved at a meeting of the senior retainers on 2m 6d of the 14th Year of Keich

Masamune. The retainer band opposed Hisataka’s appointment over Masamune, stressing the fact that Kabayama Hisataka was the younger of the two men, but the dispute was eventually resolved at a meeting of the senior retainers on 2m 6d of the 14th Year of Keich (11 March 1609). Hisataka was about to yield his position on the raised dais, the seat of honour, to Masamune when the octogenarian Niiro Musashi-no-kami Tadamoto, the most respected among the Shimazu elders, took Hisataka by the hand and made him take his rightful place. From that moment on, all opposition to Hisataka’s appointment ceased.

(11 March 1609). Hisataka was about to yield his position on the raised dais, the seat of honour, to Masamune when the octogenarian Niiro Musashi-no-kami Tadamoto, the most respected among the Shimazu elders, took Hisataka by the hand and made him take his rightful place. From that moment on, all opposition to Hisataka’s appointment ceased.

During the Okinawa raid, Kabayama Hisataka took the place of the daimyo himself in his accepted military role as the s taish

taish . The hatamoto guard was directly accountable to him, while command of the troops of the line, comprising samurai and ashigaru footsoldiers, was delegated to taish

. The hatamoto guard was directly accountable to him, while command of the troops of the line, comprising samurai and ashigaru footsoldiers, was delegated to taish or bugashira. The troops fought in units called kumi (-gumi when used as a suffix), and by 1609 even the elite mounted samurai, expressed as a number of ki, now served in organised groups rather than fighting in individual combat. The ashigaru were arranged in squads, organised according to weapon type, and sub-units of all the divisions fell under the command of officers called either kumigashira or monogashira.

or bugashira. The troops fought in units called kumi (-gumi when used as a suffix), and by 1609 even the elite mounted samurai, expressed as a number of ki, now served in organised groups rather than fighting in individual combat. The ashigaru were arranged in squads, organised according to weapon type, and sub-units of all the divisions fell under the command of officers called either kumigashira or monogashira.

The other type of role that could be assigned to a senior vassal or family member was that of a bugy who, instead of leading the fighting units, carried out various service support functions, acting as the commander’s general staff. Their number would include men in charge of equipment, provisions and supervision of communications. An important role during the Okinawa operation would have been performed by the fune bugy

who, instead of leading the fighting units, carried out various service support functions, acting as the commander’s general staff. Their number would include men in charge of equipment, provisions and supervision of communications. An important role during the Okinawa operation would have been performed by the fune bugy , who took charge of all matters relating to transport on water. Holding a position equivalent in prestige were the ikusa metsuke. As well as identifying acts of bravery and cowardice, they would investigate and assess whether any ambiguous claims of glorious achievement were true or false. While this particular samurai obsession with individual prowess kept them very busy, other tasks included the counting of heads and the identification of both victim and victor.

, who took charge of all matters relating to transport on water. Holding a position equivalent in prestige were the ikusa metsuke. As well as identifying acts of bravery and cowardice, they would investigate and assess whether any ambiguous claims of glorious achievement were true or false. While this particular samurai obsession with individual prowess kept them very busy, other tasks included the counting of heads and the identification of both victim and victor.

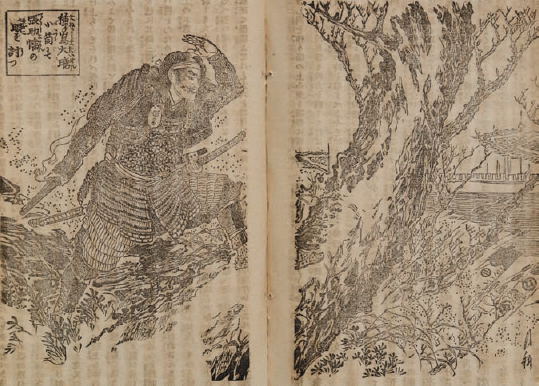

Tanegashima Daisen, the commander of the left vanguard of the Satsuma army, contemplates the fortress on Okinawa that he is about to capture. As befits the lord of the island on which European firearms first arrived, he is shown holding a smoking pistol in his right hand. This is from an 1868 compilation version of Ehon Ry ky

ky Gunki called Ehon Ry

Gunki called Ehon Ry ky

ky Gunki Mokuroku, illustrated by Ogata Gekk

Gunki Mokuroku, illustrated by Ogata Gekk (1859–1920).

(1859–1920).

Much less is known about the commanders and sub-commanders in the Ry ky

ky an defence forces. King Sh

an defence forces. King Sh Nei of Ry

Nei of Ry ky

ky had inherited the military system set up by his illustrious predecessor King Sh

had inherited the military system set up by his illustrious predecessor King Sh Shin (1465–1526), who had ruled from 1477. Throughout his long reign, Sh

Shin (1465–1526), who had ruled from 1477. Throughout his long reign, Sh Shin had tried very successfully to control the power of the aji, who were the hereditary warlords of Ry

Shin had tried very successfully to control the power of the aji, who were the hereditary warlords of Ry ky

ky . At the same time he managed to develop and strengthen an efficient centralised military system, a process that required a delicate balancing act. To achieve the first, Sh

. At the same time he managed to develop and strengthen an efficient centralised military system, a process that required a delicate balancing act. To achieve the first, Sh Shin required all the aji to reside in Shuri, where he bestowed upon them titles and prestige. A similar system would later be used by the shoguns of Tokugawa to control the daimyo. The aji’s former military roles were then taken by government appointees who were directly accountable to the king, while their weapons were collected and stored centrally in Shuri. At the heart of the Ry

Shin required all the aji to reside in Shuri, where he bestowed upon them titles and prestige. A similar system would later be used by the shoguns of Tokugawa to control the daimyo. The aji’s former military roles were then taken by government appointees who were directly accountable to the king, while their weapons were collected and stored centrally in Shuri. At the heart of the Ry ky

ky an military organisation under Sh

an military organisation under Sh Shin were the hiki, forces that could be rapidly deployed when danger threatened and who at other times carried out guard and police functions. An official was also appointed to oversee the development of artillery, a matter in which the Ry

Shin were the hiki, forces that could be rapidly deployed when danger threatened and who at other times carried out guard and police functions. An official was also appointed to oversee the development of artillery, a matter in which the Ry ky

ky an kings had always taken an interest.

an kings had always taken an interest.

King Sh Nei took no part in the fighting during the raid on his country. The closest member of the royal family involved in action was the king’s younger brother, who, at the northern fortress of Nakijin, was subjected to the Shimazu’s first assault on Okinawa. At the time of the 1609 raid, the names that often appeared in the context of military leadership were those of the members of the king’s sanshikan (Council of Three) – his closest advisers and occasional de facto rulers of the kingdom. In 1609 these were Jana Teid

Nei took no part in the fighting during the raid on his country. The closest member of the royal family involved in action was the king’s younger brother, who, at the northern fortress of Nakijin, was subjected to the Shimazu’s first assault on Okinawa. At the time of the 1609 raid, the names that often appeared in the context of military leadership were those of the members of the king’s sanshikan (Council of Three) – his closest advisers and occasional de facto rulers of the kingdom. In 1609 these were Jana Teid , Urasoe Ch

, Urasoe Ch shi and Nago Ry

shi and Nago Ry h

h . Jana Teid

. Jana Teid was an accomplished general and a successful administrator, who had spent time in his youth in China. His son-in-law led the resistance on Tokunoshima.

was an accomplished general and a successful administrator, who had spent time in his youth in China. His son-in-law led the resistance on Tokunoshima.

Army Organisation and Troop Numbers

The army of the Shimazu daimyo consisted of two categories of soldier, the samurai and the ashigaru. The samurai were the knights of old Japan. Traditionally they had been the only warriors to own and ride horses and, centuries earlier, their primary role had been to act as mounted archers. This skill was much less evident on the battlefield by 1609. The usual samurai weapon at the time of the raid was the yari, which differed from a European knight’s lance in that it was lighter and shorter, and was not carried in a crouched position.

The ashigaru were the footsoldiers of a Japanese army. Well-trained and disciplined, they had evolved over the past century from being casually recruited peasant warriors to becoming the lower ranks of the samurai class, a position that was to be formalised under the Tokugawa. Most ashigaru were organised in homogeneous groups according to the type of weapon carried: spear, arquebus or bow. The bravest ashigaru acted as standard bearers or served as the daimyo’s closest attendants, and it would only be in cases of dire emergency that trained ashigaru would be used for menial tasks like general baggage carrying, for which purpose numerous labourers were employed. The ashigaru were trained to fight in formation. The spearmen usually provided a defence for the missile troops, but could also act in an offensive capacity with their long spears.

While attendants were supplied to a samurai according to his rank, an exclusive body of samurai and ashigaru would have attended the general himself, providing personal services on a larger scale. These would include a zori tori, who, among other duties equivalent to an officer’s batman, carried footwear; grooms to lead the general’s horse; and other ashigaru to carry his provisions, helmet and weapons. Many illustrations show ashigaru in the hatamoto carrying flags, armour boxes, quivers or an assortment of spears with very elaborate ornamental scabbards.

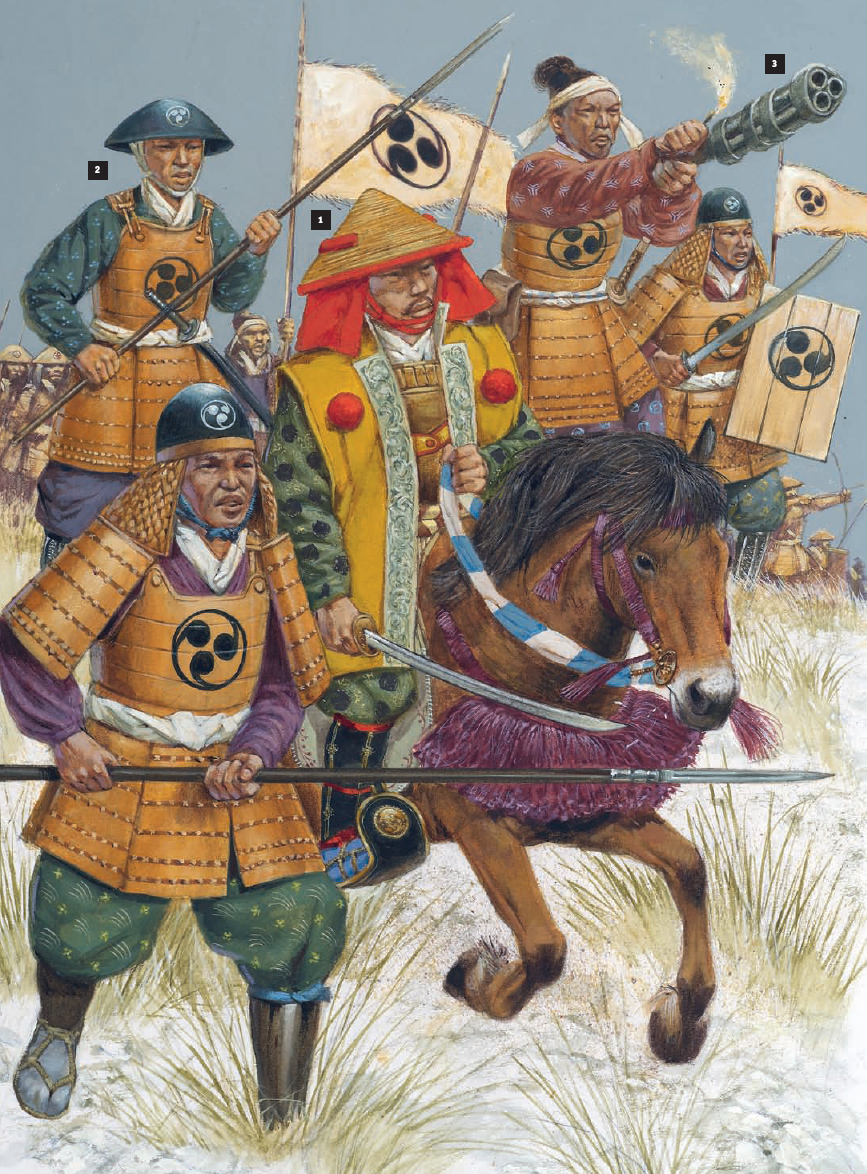

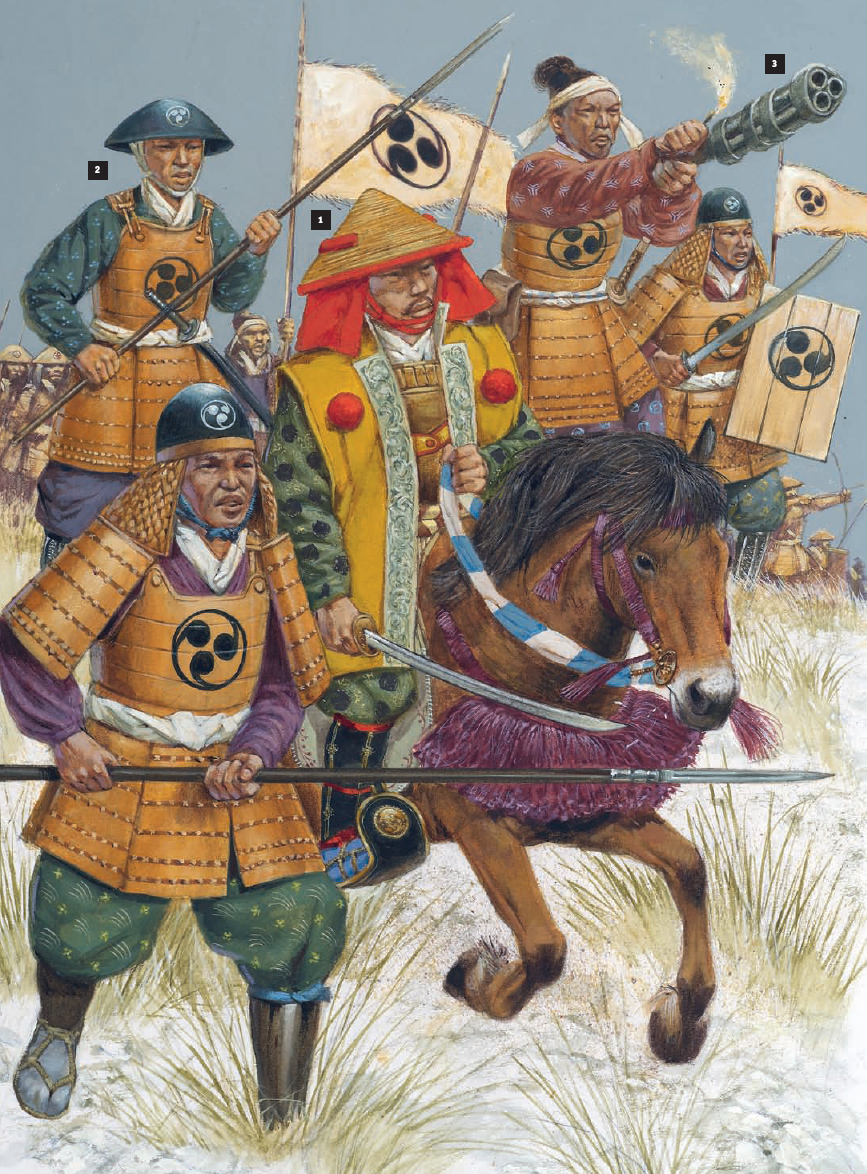

These Shimazu samurai and footsoldiers are dressed in Japanese armour of the highest quality attained during its development, with bulletproof breastplates and sturdy helmets. General Kabayama Hisataka (1) wears fine armour of a traditional, even old-fashioned style. His hatamoto guards (2) are distinguished by wearing a golden fan as their sashimono (insignia). Even the ashigaru (3) are well protected.

Written sources are contradictory with regard to the numbers of soldiers used by both sides in the Okinawa operation. Accounts cite a complement of between 1,000 and 3,000 Ry ky

ky ans mounting a defence against Satsuma. Jana Teid

ans mounting a defence against Satsuma. Jana Teid , for example, commanded 3,000 men in the defence of Naha Harbour. The numbers given for the defence of Amami-Oshima are also 3,000 with 100 for Tokunoshima, but these are the only figures that exist.

, for example, commanded 3,000 men in the defence of Naha Harbour. The numbers given for the defence of Amami-Oshima are also 3,000 with 100 for Tokunoshima, but these are the only figures that exist.

The Satsuma accounts give far more detail for the numbers of the aggressors. The overall strength of the expeditionary force depended, as was usual with any daimyo’s army, on the assessed wealth of the domain and how much of it should be devoted to a military operation. The unit of measurement was the koku, an amount of rice commonly regarded as that needed to feed one man for one year. In the case of the Shimazu, the working total was 402,180.5 koku, of which 75,000 koku was earmarked for the invasion. Iehisa’s retainers were required to supply two men for every 100 koku of their recorded wealth, making a total of 1,500 men. The remaining 320,700 koku was raised from the inhabitants of the province, who were required to supply in total 107 kanme 900 monme (404.62kg) of silver together with supplies in the form of army rice to feed 1,500 men.

Even though the retainer band was required to furnish 1,500 men, the number who went to Okinawa is commonly believed to be 3,000 men, conveyed on about 100 ships. Confirmation of this is given in Kyan Nikki which records that there were 100 samurai within a total force of 3,000 men conveyed on more than 70 ships. Kyan was well informed, and is likely to have obtained this figure from the Satsuma officials with whom he was to be closely associated after the invasion. In contrast the Satsuma eyewitness, Ichiki Magobe’e Iemoto, makes no mention of the size of the army, saying only that it was conveyed on more than 80 ships. It is possible, however, that Kyan may have been estimating the size of the army, and his figure of 100 samurai may have simply been an observation of mounted troops. Furthermore, it is not clear whether the the figure of 3,000 refers to the total headcount of soldiers, ships’ crews and labourers who sailed from Satsuma, or to the actual tally of fighting men. Similarly, there is no indication whether the smaller number of 1,500 relates only to samurai or whether it also includes their personal followers.

A detailed list of the numbers of men supplied by named retainers appears in Ry ky

ky Tosh

Tosh , showing that almost all the members of the retainer band exceeded their actual obligations. So, for example, the general of the invasion, Kabayama Hisataka, had to supply 54 men according to the ordnance, but actually supplied 60. A certain Murao Genza’emon Nyud

, showing that almost all the members of the retainer band exceeded their actual obligations. So, for example, the general of the invasion, Kabayama Hisataka, had to supply 54 men according to the ordnance, but actually supplied 60. A certain Murao Genza’emon Nyud is listed as being required to supply ‘two men, but besides this two men, making four men’. Similar notes appear next to the names of 66 other leaders who supplied 713 men in total. A separate Shimazu document provides a corresponding list of names that gives the figure of more than 100 samurai in an army of 3,000 men conveyed on 100 ships. Reference to 3,000 men on 100 ships also appears in a third document.

is listed as being required to supply ‘two men, but besides this two men, making four men’. Similar notes appear next to the names of 66 other leaders who supplied 713 men in total. A separate Shimazu document provides a corresponding list of names that gives the figure of more than 100 samurai in an army of 3,000 men conveyed on 100 ships. Reference to 3,000 men on 100 ships also appears in a third document.

The Heiromon, one of the main gates of the gusuku of Nakijin, the first castle to be attacked by the Shimazu on mainland Okinawa. There gunports on either side of the entrance, evidence of successive Ry ky

ky an kings’ expertise with early firearms. Where they did not keep pace with the times was in the European-style deployment of massed ranks of arquebuses.

an kings’ expertise with early firearms. Where they did not keep pace with the times was in the European-style deployment of massed ranks of arquebuses.

A different army listing appears in another Shimazu document where Kabayama’s general staff are named according to which of the three ‘factions’, the Kagoshima-kata, the Kokubu-kata or the Kajiki-kata, they belonged. The Kagoshima-kata provided the three bugy who went with the army – two heigu bugy

who went with the army – two heigu bugy in charge of the army and strategy, one fune bugy

in charge of the army and strategy, one fune bugy for sea transport and three bugashira. From the Kokubu-kata came nine bugashira, and a further four were supplied by the Kajiki-kata. There was also an army priest, together with over 100 unspecified samurai and 30 bearers of weapons. To these were added ships’ carpenters.

for sea transport and three bugashira. From the Kokubu-kata came nine bugashira, and a further four were supplied by the Kajiki-kata. There was also an army priest, together with over 100 unspecified samurai and 30 bearers of weapons. To these were added ships’ carpenters.

The deployment of ashigaru weapon groups made use of fighting men in a reserve capacity, so it would not have been difficult to amass a total of 3,000 fighting men. However, as 100 ships would need a large number of crewmen, it is highly improbable the latter were included in the documented total of 3,000. Porters, labourers and boatmen would have also added to the number. In Korea in 1592, about 65% of a typical daimyo’s manpower quota could have been made up from non-combatant staff. In one detailed example, Got Sumiharu sent 220 fighting men to Korea with 485 men in supporting functions. A similar percentage is found on analysing the contingent that was supposed to accompany Shimazu Yoshihiro to Korea in 1592, when the army of Satsuma should have consisted of 600 samurai and 3,600 ashigaru out of a grand total of 15,000 men. The number actually supplied by Satsuma was 10,000, not 15,000, indicating that after being defeated by Hideyoshi in 1587, the Shimazu simply could not meet the obligation. Yet even 10,000 men for a seaborne expedition in 1592 was a much larger number than the 3,000 assembled by the Satsuma in 1609. This may have meant they were in even more desperate financial circumstances after their defeat at Sekigahara. Alternatively, as they were able to field another large army of 10,000 for the siege of Osaka in 1614, it is more likely this figure was all they felt was necessary to conquer Ry

Sumiharu sent 220 fighting men to Korea with 485 men in supporting functions. A similar percentage is found on analysing the contingent that was supposed to accompany Shimazu Yoshihiro to Korea in 1592, when the army of Satsuma should have consisted of 600 samurai and 3,600 ashigaru out of a grand total of 15,000 men. The number actually supplied by Satsuma was 10,000, not 15,000, indicating that after being defeated by Hideyoshi in 1587, the Shimazu simply could not meet the obligation. Yet even 10,000 men for a seaborne expedition in 1592 was a much larger number than the 3,000 assembled by the Satsuma in 1609. This may have meant they were in even more desperate financial circumstances after their defeat at Sekigahara. Alternatively, as they were able to field another large army of 10,000 for the siege of Osaka in 1614, it is more likely this figure was all they felt was necessary to conquer Ry ky

ky in a short and decisive operation.

in a short and decisive operation.

As a final note on troop numbers and organisation, useful information may be gleaned from the gunkimono. Shimazu Ry ky

ky Gunseiki appears remarkably precise and very valuable. It lists every general’s name and gives a breakdown of his followers according to weapon groups. When combined with Ehon Ry

Gunseiki appears remarkably precise and very valuable. It lists every general’s name and gives a breakdown of his followers according to weapon groups. When combined with Ehon Ry ky

ky Gunki, which is effectively an illustrated version of the gunkimono, one is given a complete and detailed account of each unit of the invading army, including each general’s individual heraldry and even the heraldic device on the sails of his ship. Unfortunately it is not a useful historical source, because the names of the generals do not correspond to the names in the reliable household accounts, nor do the figures of the troops they are said to command add up. Tanegashima Daisen, who is named as commanding the left wing of the vanguard, is shown as having troops numbering 4,106, but the subtotal written at the end of his section is almost four times greater at 20,370. The grand total for the Shimazu army using such subtotals works out at an astounding 103,770 men, which may be compared with the 10,000 they sent to Korea as part of a total Japanese army of 138,000, drawn from all the daimyo that took part.

Gunki, which is effectively an illustrated version of the gunkimono, one is given a complete and detailed account of each unit of the invading army, including each general’s individual heraldry and even the heraldic device on the sails of his ship. Unfortunately it is not a useful historical source, because the names of the generals do not correspond to the names in the reliable household accounts, nor do the figures of the troops they are said to command add up. Tanegashima Daisen, who is named as commanding the left wing of the vanguard, is shown as having troops numbering 4,106, but the subtotal written at the end of his section is almost four times greater at 20,370. The grand total for the Shimazu army using such subtotals works out at an astounding 103,770 men, which may be compared with the 10,000 they sent to Korea as part of a total Japanese army of 138,000, drawn from all the daimyo that took part.

If the numbers are unreliable, the breakdown of the army by weaponry and organisation may contain more useful information. The Shimazu family documents, although precise about the names of the bugy and bugashira in separate, matching accounts, reveal a complete lack of understanding as to how the army was actually arranged. Shimazu Ry

and bugashira in separate, matching accounts, reveal a complete lack of understanding as to how the army was actually arranged. Shimazu Ry ky

ky Gunseiki, however, describes the army being split into different sonae of vanguard (left and right), 2nd (left and right), 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th and rearguard. This matches very similar arrangements noted for other armies of the period, so is likely to be based on fact in all but the total numbers of troops. As for the internal organisation of the sonae, this is again addressed in Shimazu Ry

Gunseiki, however, describes the army being split into different sonae of vanguard (left and right), 2nd (left and right), 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th and rearguard. This matches very similar arrangements noted for other armies of the period, so is likely to be based on fact in all but the total numbers of troops. As for the internal organisation of the sonae, this is again addressed in Shimazu Ry ky

ky Gunseiki, where Tanegashima Daisen is said to command three ashigaru units of equal numbers of spears, bows and guns, all led by monogashira. There is also reference to a squad armed with axes and, for signalling purposes, with war drums and bells. Samurai, both mounted and on foot, are described, as well as a designated rearguard for the division. Equipment in other sonae includes kumade and conch shell trumpets. The other sonae are similarly arranged, except that the 6th sonae, the main body under Niiro Musashi-no-kami, contains the sole mention of flag carriers. All the numbers cited are very large, and, as already noted, are not internally consistent. The grand total of the army is swollen by the inclusion of a huge number of named samurai and their followers in the rearguard, and additionally, no fewer than eight named warriors with the family name of Shimazu, all with huge retinues (one having 10,000 samurai to himself). There are also five metsuke, in accordance with what one might expect, and an interesting breakdown of the non-combatant support function, including the men in charge of storing rice, followed by those who transport it by packhorse, cart or on their own backs.

Gunseiki, where Tanegashima Daisen is said to command three ashigaru units of equal numbers of spears, bows and guns, all led by monogashira. There is also reference to a squad armed with axes and, for signalling purposes, with war drums and bells. Samurai, both mounted and on foot, are described, as well as a designated rearguard for the division. Equipment in other sonae includes kumade and conch shell trumpets. The other sonae are similarly arranged, except that the 6th sonae, the main body under Niiro Musashi-no-kami, contains the sole mention of flag carriers. All the numbers cited are very large, and, as already noted, are not internally consistent. The grand total of the army is swollen by the inclusion of a huge number of named samurai and their followers in the rearguard, and additionally, no fewer than eight named warriors with the family name of Shimazu, all with huge retinues (one having 10,000 samurai to himself). There are also five metsuke, in accordance with what one might expect, and an interesting breakdown of the non-combatant support function, including the men in charge of storing rice, followed by those who transport it by packhorse, cart or on their own backs.

Based on the available evidence, an estimate of the likely size and composition of the Shimazu army is as follows:

| General Staff |

|

| General |

|

| Second-in-Command |

|

Bugy |

3 |

| Bugashira |

16 |

| Attendants |

100 |

| Mounted Samurai |

100 |

| Attendants |

200 |

| Foot Samurai |

700 |

| Ashigaru |

|

| Arquebus |

800 |

| Spear |

800 |

| Bow |

300 |

| Others |

200 |

| Total fighting troops |

3,000 |

| Labourers |

2,000 |

| Sailors |

3,000 |

It is likely that around 3,000 fighting men with 5,000 supporters went to Okinawa. These figures are one-fifteenth of the number cited in Shimazu Ry ky

ky Gunseiki.

Gunseiki.

Arms and Armour

The Shimazu samurai and ashigaru were well armed and well armoured. The samurai were predominately spearmen with swords as a secondary weapon. The blades of the yari spears were very sharp on both edges, with their tangs sunk into stout oak shafts. This made the yari into a weapon unsuitable for slashing but ideal for stabbing – the best technique to use from a saddle. A useful variation was a cross-bladed spear that enabled a samurai to pull an opponent from his horse. If a samurai wished to deliver slashing strokes from horseback then a better choice than a yari was the naginata, a polearm with a long curved blade, or the spectacular nodachi, a very long sword with a very strong and very long handle. When having to fight dismounted, the yari would be a samurai’s primary weapon of choice, as was evidenced on Okinawa. There are no references in the literature to cavalry charges, but horses would have been well used in the rapid movement overland.

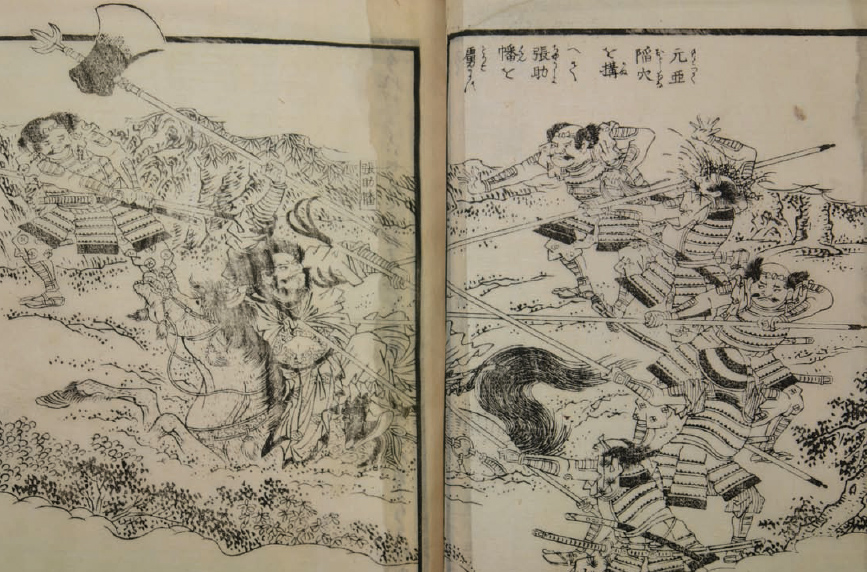

This general of the Okinawa army (1) wears a mixture of Chinese and Japanese styles. His troops (2) are more simply dressed in armour of the haramaki style, open at the back. Some carry the simple three-barrelled firearms (3) favoured by the Ry ky

ky ans. Their use of swords differs from the Japanese, as they wield the short wakizashi in one hand and carry a small shield in the other. They fight under the ‘three commas’ flag of the king of Ry

ans. Their use of swords differs from the Japanese, as they wield the short wakizashi in one hand and carry a small shield in the other. They fight under the ‘three commas’ flag of the king of Ry ky

ky .

.

The samurai’s other main weapon was, of course, the famous katana. This classic samurai sword would be forged to perfection, with a razor-sharp edge within a resilient body. Every samurai possessed at least one pair of swords, the katana and the shorter wakizashi. Both seem to have been carried into battle along with a tant (dagger). The samurai never used shields; instead, the katana acted as both sword and shield, its resilience enabling the samurai to deflect a blow aimed at him by knocking the attacking sword to one side with the flat of the blade, and then following up with a stroke of his own.

(dagger). The samurai never used shields; instead, the katana acted as both sword and shield, its resilience enabling the samurai to deflect a blow aimed at him by knocking the attacking sword to one side with the flat of the blade, and then following up with a stroke of his own.

Samurai wore strong and flexible armour. The traditional style of manufacture had been for the armour plates to be made from individual iron or leather scales laced together. By 1609, the design had been modified to solid-plate body armour, thus giving better protection against gunfire. Lamellar sections, however, continued to be found in both thigh and shoulder guards. Armoured arm sleeves and shin guards protected the limbs. Above the neck would be the most striking part of a samurai’s armour – an iron mask to protect the face. A moustache made of horsehair was often added to the mask and the mouthpiece decorated with a sinister grin around white teeth. The helmet was very solid, but senior samurai, and many daimyo, would use the design of the helmet crown to give a personal touch to what was otherwise very practical protection, using wood and papier-mâché to build up the surface into fantastic shapes.

The other way in which an individual samurai or ashigaru would be recognised in the heat of battle was by wearing a small identifying device on his back, called a sashimono. This would often be in the form of a flag in a wooden holder, displaying the daimyo’s mon on a coloured background so that the unit could easily be recognised. While this would apply to most rank-and-file samurai, senior samurai would be allowed to have their own mon, or sometimes their family name, displayed on the flag. Golden fans and plumes of feathers could replace the small flag, but the most spectacular form of sashimono was the horo. This was a cloak stretched over a bamboo framework that had become a decorative appendage for a daimyo’s elite samurai who acted as tsukai-ban (courier guards). The horo filled with air as he rode across the battlefield, and the bright colours made him visible to friend and foe. There is evidence that excellent communications were maintained between separate units of the Satsuma army on Okinawa, and the tsukai-ban would have been crucial in achieving this. The ashigaru wore simple suits of iron armour, usually consisting of a body armour from which hung a skirt of protective plates. The breastplate bore the mon of the daimyo, a device that also appeared on the simple lampshade-shaped helmet known as the jingasa. Armour protection for the arms and calves was also often provided.

All accounts of the 1609 operation stress the vital role played by firearms in the Shimazu advance. As befitted the rulers of the province that had witnessed the arrival of the first European-style firearms on Japanese shores in 1543, the Shimazu army had never been behind the times in gunpowder technology. Like all other Japanese daimyo, however, their use of firearms was largely confined to the hand-held arquebus rather than cannon. The Shimazu, in fact, seem to have suffered the consequences of cannon more than most, having twice come under fire from European-made big guns owned by the Otomo at the battles of Mimigawa in 1578 and Usuki in 1586. Yet in spite of their previous experiences, the Shimazu do not appear to have taken the heavy weaponry of a siege train with them to Okinawa. Instead, just as in the case of Korea in 1592, hundreds of bullets were to pour from the muzzles of the guns held by the well-disciplined ashigaru in the Shimazu army. The arquebus was fired when a smouldering match, fastened into a serpentine, was dropped onto the touch-hole. To prevent premature discharges, the touch-hole was closed until the point of firing by a tight-fitting brass cover. One disadvantage of the arquebus was its slow loading time compared to the bow, making it necessary for archers to provide cover while reloading took place. The experience of the battle of Nagashino in 1575 had confirmed volley firing as the most effective way of using the arquebus, but it also illustrated the iron-hard discipline needed to make it work.

The use of volley firing by squads of ashigaru armed with arquebuses was a decisive factor in the victory achieved by the Shimazu over the Ry ky

ky Kingdom. Arquebuses are shown here in the hands of a precisely dressed re-enactment group at Oshi castle in 2006.

Kingdom. Arquebuses are shown here in the hands of a precisely dressed re-enactment group at Oshi castle in 2006.

The inclusion of bows in the Shimazu army shows that even at this late stage in samurai warfare, archers were still prized. Some may have been highly trained sharpshooters used as skirmishers or for sniping, but their most important role was to fire volleys of arrows. Even though bows had a shorter range than the arquebus and required a more experienced operator, their rate of fire was more rapid and enemy arrows could be re-used. Archers were supported by carriers who were at hand with large quiver boxes, each containing 100 arrows. The preferred range for firing was from 30 to 80m, and the bow had a maximum effective range of 380m.

The earliest ashigaru spears had been the same length as samurai ones, and were wielded just as freely in the conflicts of the Onin War. From about 1530 onwards, the shaft of the ashigaru weapon lengthened noticeably, producing the nagae-yari that was more akin to a pike. The ashigaru spearmen were trained to fight as a group, formed up in a line of two or three ranks with their spearpoints even, thus showing certain similarities to European pikemen. Other ashigaru units included players of drums, bells and conch shell trumpets, wielders of rakes and axes and importantly, bearers of flags. Long banners called nobori were used for the identification of units, while the daimyo’s uma jirushi (battle-standards) would attract some of the fiercest fighting. Visual communications depended largely on the use of flags, while the uma jirushi and massed nobori played a vital role in orientation on a battlefield.

Ignoring the obvious exaggerations of total numbers, the weaponry described in Shimazu Ry ky

ky Gunseiki does not differ significantly from that described in the only other guide on the subject, a brief summary within the Shimazu archives of the weaponry supplied for the army. Curiously, spears are not mentioned:

Gunseiki does not differ significantly from that described in the only other guide on the subject, a brief summary within the Shimazu archives of the weaponry supplied for the army. Curiously, spears are not mentioned:

| Arquebuses |

734 |

| Bullets |

37,200 |

| Bows |

117 |

| Quivers |

117 |

| Bowstrings |

351 (two spare bowstrings per bow) |

| Kuwa |

397 |

| Axes, hatchets, other tools |

398 |

Kuwa were sickle blades mounted on long shafts, which would have been useful for sea fighting should the Ry ky

ky an navy have tried to intercept the raid. Axes and hatchets would have been employed for construction projects and siege work, and may have been used by non-combatant labourers. The number of arquebuses implies that the Shimazu put great faith in the power of bullets when delivered in controlled volleys, and may be compared in number to the 1,500 arquebuses used by the larger Shimazu army of 1592 in Korea, an operation that confirmed the devastating effects of mass volleys from firearms. By means of such tactics, the Japanese invaders had taken Korean walled cities without lengthy sieges, a point that must have been in the mind of Kabayama Hisataka when he made preparations to deploy his army against the castles of Okinawa, which also had low walls, low parapets and little opportunity for defensive fire. Controlled volleys would have swept the defenders from their parapets, allowing the samurai to mount scaling ladders and fight their way onto the walls.

an navy have tried to intercept the raid. Axes and hatchets would have been employed for construction projects and siege work, and may have been used by non-combatant labourers. The number of arquebuses implies that the Shimazu put great faith in the power of bullets when delivered in controlled volleys, and may be compared in number to the 1,500 arquebuses used by the larger Shimazu army of 1592 in Korea, an operation that confirmed the devastating effects of mass volleys from firearms. By means of such tactics, the Japanese invaders had taken Korean walled cities without lengthy sieges, a point that must have been in the mind of Kabayama Hisataka when he made preparations to deploy his army against the castles of Okinawa, which also had low walls, low parapets and little opportunity for defensive fire. Controlled volleys would have swept the defenders from their parapets, allowing the samurai to mount scaling ladders and fight their way onto the walls.

A written compilation of daimyo heraldry, O Uma Jirushi, produced early in the Edo Period, includes reference to Shimazu Iehisa and this gives a very good indication as to how the Shimazu army on Okinawa would have appeared overall. The designs shown are very similar to contemporary illustrations on painted screens of the Shimazu army at the battle of Sekigahara. Because Kabayama Hisataka led the army on Iehisa’s behalf, it is reasonable to assume that the force had the same overall appearance as if the daimyo himself were present. General Kabayama, in accordance with his rank, would have worn an elaborate suit of armour, although no details of it have survived. The o uma jirushi (great battle-standard) of the Shimazu was a three-dimensional bunch of black cock’s feathers. The nobori banners were diagonally divided in two, with black below and white above, and bore the Shimazu mon of a black cross in a ring (said to be derived from the shape of a horse’s bit, and with no Christian connotations whatsoever) in the upper section. One particularly large nobori acted as the ko uma jirushi (lesser battle-standard). This nobori had a small flag attached to it that was white with the Shimazu mon. One interesting feature of Kabayama Hisataka’s hatamoto was their use of a sashimono that was not a flag. Instead it was a wooden gold-lacquered fan. The samurai in the line infantry and the ashigaru would, however, have worn flag sashimono, more typically consisting of a flag with a white background on which was inscribed the mon, or the same with colours reversed. Tools would have been wielded by non-combatant labourers who, although unlikely to have been wearing armour, may well have been issued with a jingasa. The mon of the Shimazu is likely to have been stencilled on to their coats.

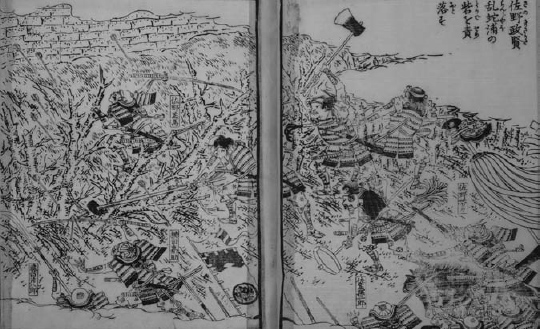

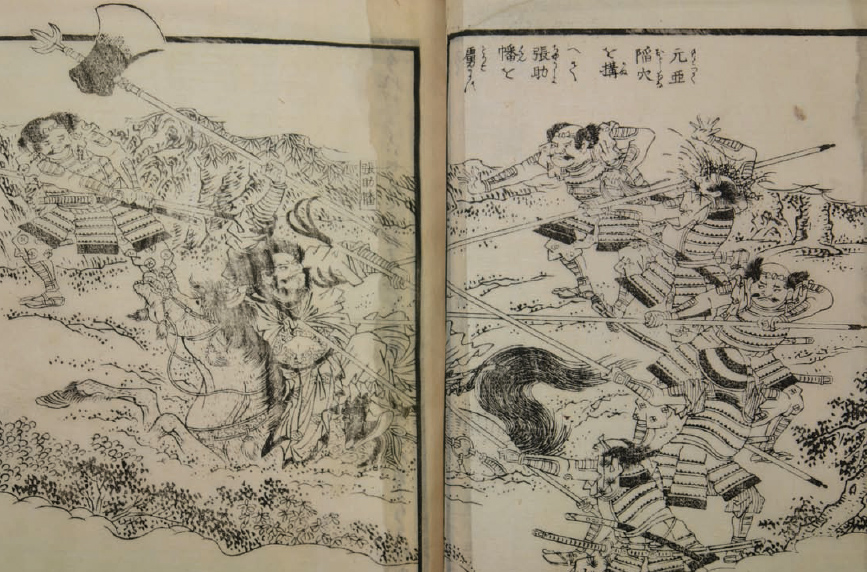

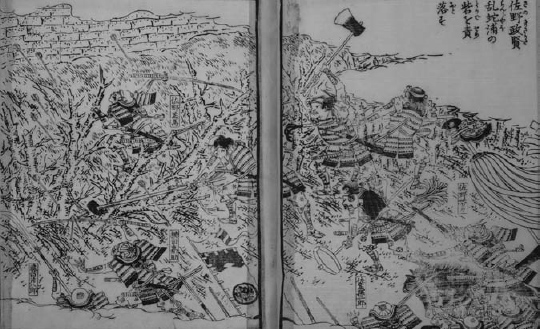

The 5th sonae of the Shimazu army, under Sano Masakata, attacks an Okinawan fortress under a hail of arrows, cutting its way through rudimentary defences of tree branches using axes, hammers and mallets. (ERG)

The details of the arms and armour of the defenders of Ry ky

ky are very sketchy when compared to the information available for the invaders. From written accounts, one may conclude that although the Ry

are very sketchy when compared to the information available for the invaders. From written accounts, one may conclude that although the Ry ky

ky an weapons were not as good as those of Satsuma, they were by no means primitive. It is well established that the Ry

an weapons were not as good as those of Satsuma, they were by no means primitive. It is well established that the Ry ky

ky ans conducted trade between China and Japan involving weapons. However during the 1450s, these armaments were needed at home to defend against wak

ans conducted trade between China and Japan involving weapons. However during the 1450s, these armaments were needed at home to defend against wak , so the inhabitants of Fujian province in China were banned from selling weapons to Ry

, so the inhabitants of Fujian province in China were banned from selling weapons to Ry ky

ky in private dealings. The Japanese sword was valued as much on Okinawa as it was in China, but it is known that adaptations were made to the weapon by fitting it with a handle that would allow fighting with one hand. As the long katana would not have been practical in this regard, it is assumed that new handles were fitted to the shorter wakizashi. Small wooden shields were sometimes carried in the left hand. The Ry

in private dealings. The Japanese sword was valued as much on Okinawa as it was in China, but it is known that adaptations were made to the weapon by fitting it with a handle that would allow fighting with one hand. As the long katana would not have been practical in this regard, it is assumed that new handles were fitted to the shorter wakizashi. Small wooden shields were sometimes carried in the left hand. The Ry ky

ky an forces were likely, therefore, to have presented a mix of Chinese and Japanese armaments, deploying bows, swords, spears and guns. Halberds, either the broad bladed Chinese version or the very similar Japanese naginata with blades more akin to swords, were also used.

an forces were likely, therefore, to have presented a mix of Chinese and Japanese armaments, deploying bows, swords, spears and guns. Halberds, either the broad bladed Chinese version or the very similar Japanese naginata with blades more akin to swords, were also used.

The kings of Ry ky

ky had also been early converts to firearms. The shipwrecked Koreans of 1450 noted that the Ry

had also been early converts to firearms. The shipwrecked Koreans of 1450 noted that the Ry ky

ky an use of firearms was similar to their own even at that early stage. These would have been the short-barrelled weapons obtained from China, which were made with a short iron tube fixed to a long wooden shaft. The barrel was wider round its touch-hole and had a slightly conical muzzle terminating in an elongated aperture. Pictures of similar European models show the stock of the gun being held tightly under the left arm while the right hand applied the lighted match. This type of gun is known to have been used in Japan as late as 1548 at the battle of Uedahara, but it was never widely adopted in Japanese warfare and was immediately scrapped when the much more sophisticated model based on the European arquebus came into general use. A popular version used on Ry

an use of firearms was similar to their own even at that early stage. These would have been the short-barrelled weapons obtained from China, which were made with a short iron tube fixed to a long wooden shaft. The barrel was wider round its touch-hole and had a slightly conical muzzle terminating in an elongated aperture. Pictures of similar European models show the stock of the gun being held tightly under the left arm while the right hand applied the lighted match. This type of gun is known to have been used in Japan as late as 1548 at the battle of Uedahara, but it was never widely adopted in Japanese warfare and was immediately scrapped when the much more sophisticated model based on the European arquebus came into general use. A popular version used on Ry ky

ky had three barrels. It is highly probable the Ry

had three barrels. It is highly probable the Ry ky

ky ans were aware of the existence of the European-style arquebus, even though Kyan’s diary refers to the battle at Tairabashi with the words: ‘The enemy attacked the bridge in a hail of bullets. We did not know about guns like these.’ Such a remark probably indicates his unfamiliarity with volley-firing techniques. It is known that the Ry

ans were aware of the existence of the European-style arquebus, even though Kyan’s diary refers to the battle at Tairabashi with the words: ‘The enemy attacked the bridge in a hail of bullets. We did not know about guns like these.’ Such a remark probably indicates his unfamiliarity with volley-firing techniques. It is known that the Ry ky

ky ans possessed cannon of a type known as ishibiya, a name later given to artillery that fired a shot of one kanme (3.75kg) or more. This is consistent with shot of between 7 and 9cm in diameter that has been excavated from the site of Shuri Castle. Cannon were also mounted in the defences of Naha Port.

ans possessed cannon of a type known as ishibiya, a name later given to artillery that fired a shot of one kanme (3.75kg) or more. This is consistent with shot of between 7 and 9cm in diameter that has been excavated from the site of Shuri Castle. Cannon were also mounted in the defences of Naha Port.

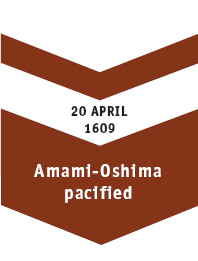

A mounted officer in the Ry ky

ky an army depicted in armour of the Chinese Ming dynasty, is cornered by a group of Satsuma samurai, who stab him with their spears and attempt to drag him from his horse using kumade. (ERG)

an army depicted in armour of the Chinese Ming dynasty, is cornered by a group of Satsuma samurai, who stab him with their spears and attempt to drag him from his horse using kumade. (ERG)

No examples of Ry ky

ky an armour have survived, but in the illustrations prepared for Ehon Ry

an armour have survived, but in the illustrations prepared for Ehon Ry ky

ky Gunki in about 1802, the artist depicted the generals of Okinawa wearing Chinese-style armour, resembling officers of the Great Ming. It may have been artistic convention to represent the soldiers of a kingdom regarded by most Japanese as wonderfully exotic in this way, but the illustrations could well reflect an element of truth. Even though this is a work of historical fiction based on the exaggerated gunkimono accounts of the raid, representations of samurai armour and equipment are meticulous in their detail. Generals on Okinawa are also shown wearing a mixture of Chinese and Japanese armour, often with a Japanese-style jinbaori (surcoat) and the use of a helmet not unlike the jingasa of the Japanese ashigaru. Other Ry

Gunki in about 1802, the artist depicted the generals of Okinawa wearing Chinese-style armour, resembling officers of the Great Ming. It may have been artistic convention to represent the soldiers of a kingdom regarded by most Japanese as wonderfully exotic in this way, but the illustrations could well reflect an element of truth. Even though this is a work of historical fiction based on the exaggerated gunkimono accounts of the raid, representations of samurai armour and equipment are meticulous in their detail. Generals on Okinawa are also shown wearing a mixture of Chinese and Japanese armour, often with a Japanese-style jinbaori (surcoat) and the use of a helmet not unlike the jingasa of the Japanese ashigaru. Other Ry ky

ky an warriors wore Japanese-style haramaki armour that was open at the back. Lower-class warriors on Okinawa were more simply dressed and wore no defensive armour. Instead they appear to have worn the ordinary attire common in Ry

an warriors wore Japanese-style haramaki armour that was open at the back. Lower-class warriors on Okinawa were more simply dressed and wore no defensive armour. Instead they appear to have worn the ordinary attire common in Ry ky

ky , consisting of a kimono-like robe tied at the waist, and a headcloth. Ry

, consisting of a kimono-like robe tied at the waist, and a headcloth. Ry ky

ky an soldiers marched under the ‘three commas’ banner of their kings and other triangular embroidered flags in the Chinese style. Long trumpets and war drums provided their musical accompaniment.

an soldiers marched under the ‘three commas’ banner of their kings and other triangular embroidered flags in the Chinese style. Long trumpets and war drums provided their musical accompaniment.

Both the Ry ky

ky ans and the Shimazu were great sailors, with active sea communications between the numerous islands they each controlled and contested. The ships that conveyed the Satsuma army to Okinawa would have been of two types, the ataka bune and the sengoku bune. The ataka bune were the warships of any daimyo’s navy and had been employed as troop transports and (much less successfully) as warships during the invasion of Korea. No ataka bune has survived, but combined with a few illustrations on painted screens, it is possible to reconstruct their appearance with great accuracy. A typical ataka bune looked like a floating wooden box. The whole of the side surface was one blank wall of thick wooden planks which protected the oarsmen and the samurai, and was pierced with small loopholes for guns and bows. The open upper deck was shielded by a low bulwark that was, in fact, an extension of the side walls. In some versions a cabin, again very solidly built, sat on the deck. In addition to the oar propulsion, there was a mast from which a large sail was hung bearing the daimyo’s mon in a bold stencilled or painted design. In a manner typical of most Japanese ships of the time, the mast was pivoted centrally and very delicately balanced so that, using rollers on top of the supports, it could be folded down when the ship went into action. The normal complement of an ataka bune was 80 oarsmen and 60 fighting men, with three cannon and 30 arquebuses. The sleeker sengoku bune (1,000-koku ship) was the workaday transport of the Edo Period, and these were pressed into service for the raid. Like the ataka bune, the ships would have been ornamented with the Shimazu mon stencilled onto the middle of their sails.

ans and the Shimazu were great sailors, with active sea communications between the numerous islands they each controlled and contested. The ships that conveyed the Satsuma army to Okinawa would have been of two types, the ataka bune and the sengoku bune. The ataka bune were the warships of any daimyo’s navy and had been employed as troop transports and (much less successfully) as warships during the invasion of Korea. No ataka bune has survived, but combined with a few illustrations on painted screens, it is possible to reconstruct their appearance with great accuracy. A typical ataka bune looked like a floating wooden box. The whole of the side surface was one blank wall of thick wooden planks which protected the oarsmen and the samurai, and was pierced with small loopholes for guns and bows. The open upper deck was shielded by a low bulwark that was, in fact, an extension of the side walls. In some versions a cabin, again very solidly built, sat on the deck. In addition to the oar propulsion, there was a mast from which a large sail was hung bearing the daimyo’s mon in a bold stencilled or painted design. In a manner typical of most Japanese ships of the time, the mast was pivoted centrally and very delicately balanced so that, using rollers on top of the supports, it could be folded down when the ship went into action. The normal complement of an ataka bune was 80 oarsmen and 60 fighting men, with three cannon and 30 arquebuses. The sleeker sengoku bune (1,000-koku ship) was the workaday transport of the Edo Period, and these were pressed into service for the raid. Like the ataka bune, the ships would have been ornamented with the Shimazu mon stencilled onto the middle of their sails.

ky

ky is more comprehensive, but no book or article contains more than a brief mention of the war through which it all began, and only one academic article on the subject has ever been published in any European language. This is ‘Die Ry

is more comprehensive, but no book or article contains more than a brief mention of the war through which it all began, and only one academic article on the subject has ever been published in any European language. This is ‘Die Ry ky

ky Expedition Unter Shimazu Iehisa’ by R. Binkenstein, which was published in an early issue of Monumenta Nipponica in 1941. Binkenstein, however, made no use of the primary sources referred to below. His sources were largely confined to gunkimono style accounts of the campaign, where the exploits of the brave Shimazu samurai were blatantly exaggerated for the benefit of their descendants, similar to the famous medieval gunkimono such as Heike Monogatari and Taiheiki. Recognising these limitations, Binkenstein included little discussion of the invasion itself and concentrated instead on the events leading up to it.

Expedition Unter Shimazu Iehisa’ by R. Binkenstein, which was published in an early issue of Monumenta Nipponica in 1941. Binkenstein, however, made no use of the primary sources referred to below. His sources were largely confined to gunkimono style accounts of the campaign, where the exploits of the brave Shimazu samurai were blatantly exaggerated for the benefit of their descendants, similar to the famous medieval gunkimono such as Heike Monogatari and Taiheiki. Recognising these limitations, Binkenstein included little discussion of the invasion itself and concentrated instead on the events leading up to it.