THE SUBJECT OF THE NEWGATE NOVEL: CRIME, INTEREST, WHAT NOVELS ARE ABOUT

The Victorian novel—whether we define the term by author, style, or monarch—has its beginning in a moment of moral controversy. Oliver Twist, Dickens’s first work conceived as a novel from the outset, began publication in 1837 and continued through Victoria’s ascension to the throne. While it never quite reached the heights of popularity achieved by The Pickwick Papers, this “first major Victorian novel”1 was an undoubted success, spurring numerous imitations and theatrical adaptations. Yet, for a number of months toward the end of its run, the novel that a young queen, just six months into her reign, deemed “excessively interesting” was not the most popular novel dealing with underworld themes.2 It was not even the most popular novel serialized in Bentley’s Miscellany. That unofficial title belonged to William Harrison Ainsworth’s Jack Sheppard, published alongside Oliver Twist in Bentley’s beginning in 1839. Influenced in no small part by the popularity of Oliver Twist, and by the popularity of the highwayman Dick Turpin in his earlier Rookwood, Ainsworth focused his “romance” on the life of the famed eighteenth-century housebreaker who had three times escaped from Newgate Prison. The novel’s popularity reached the levels of a full-scale cultural phenomenon. As John Forster wrote, in the Examiner, of the novel’s numerous theatrical adaptations:

Jack Sheppard is the attraction at the Adelphi; Jack Sheppard is the bill of fare at the Surrey; Jack Sheppard is the choice example of morals and conduct held forth to the young citizens at the City of London; Jack Sheppard reigns over the Victoria; Jack Sheppard rejoices crowds in the Pavillion; Jack Sheppard is the favourite at the Queen’s; and at Sadler’s Wells there is no profit but of Jack Sheppard.3

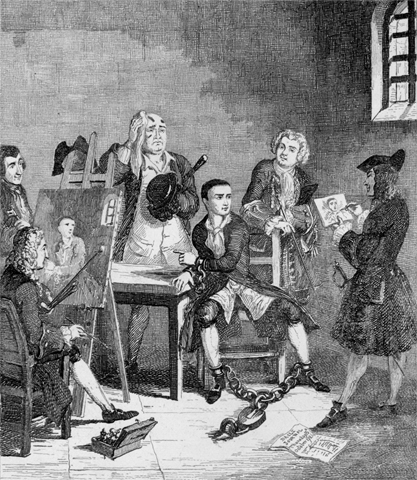

“Nix my dolly, pals, fake away,” the “flash”—that is, slang—song from J. B. Buckstone’s dramatization at the Adelphi became ubiquitous throughout London: “it deafened us in the streets. … It clanged at mid-day from the steeples of St. Giles … [I]t was whistled by every dirty guttersnipe, and chanted in drawing rooms by fair lips.”4 Thackeray reports that at the Coubourg, another theater, “people are waiting around the lobbies, selling Shepherd-bags [sic]—a bag containing a few locks that is, a screw driver, and iron lever.”5 As Keith Hollingsworth puts it, Ainsworth’s novel, and the cultural phenomenon it inspired, became “the high point of the Newgate novel as entertainment.”6

Jack Sheppard, then, was popular. But, as many critics hastened to point out, it was also bad: bad in quality, bad in morals. Worse, it was not an isolated incident. As a review in the Athenaeum put it in 1839, “Jack Sheppard … is a bad book, and what is worse, it is of a class of bad books, got up for a bad public.”7 More worrying than Jack Sheppard itself was the fact that the demands of the “bad public” would produce more of this “bad class of books.” That genre—the “bad class of books”—were the Newgate novels: novels dealing with crime and criminals. Listing further characteristics, as is usually the case with literary moments, seems to be of limited utility. The stories usually, but not always, took place in the eighteenth century. They usually, but not always, were based on characters from the biographies found in the Newgate Calendar. They sometimes, but not always, took place in London. Yet, if we cannot say precisely what the Newgate novel was, as such, we can at least offer a reasonably complete list of what these novels were: Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s Paul Clifford (1830) and Eugene Aram (1832),8 Ainsworth’s Rookwood (1834) and Jack Sheppard (1839), and Dickens’s Oliver Twist (1838).9

Bulwer, Ainsworth, and Dickens—when it comes to literary history, clearly, one of these things is not like the others. But how do we explain the fact that, from this “bad class of books,” Oliver Twist is the only one that is still read? When, in the context of larger discussions of the period, critics make reference to the Newgate novel—and there seems to be an increasing agreement on its importance—it is Dickens’s novel that stands in for the rest. D. A. Miller, for example, refers to the “Newgate novel” as one of four traditions, along with sensation fiction, detective fiction, and realist fiction, that define, in practical terms, the “nineteenth-century novel.”10 Far from discussing a tradition as a whole, though, he confines his discussion to Oliver Twist. For Franco Moretti, Newgate novels play the role of describing the eastern part of London: “West of Regent Street, silver-fork novels; and east of it, in the City … not really City novels, but Newgate ones.”11 To describe this group of novels, Moretti takes the same approach as Miller: “Stories of crime, of criminals, like Oliver Twist.” Differences in canonicity and familiarity may indicate a quirk of literary history or a qualitative evaluation—we remember the good Newgate novel, and we forget the bad ones—but it is not taken to say much about genre.

What I will argue in this chapter, though, is that a good part of the reason that Oliver Twist is read as our Newgate novel of choice, instead of the more popular Jack Sheppard, is precisely because it is not a story “of crime, of criminals”—it may have criminals in it, but it is not understood to be about crime. During its publication, John Forster wrote approvingly of the “delicacy of natural sentiment” evident in Dickens’s novel, in contrast to other novels on similar themes.12 Though Forster was not the most impartial voice when it came to Dickens, we can see the same position taken in a review published in the Monthly Chronicle:

We have somewhere seen the names of Mr. Dickens and Mr. Ainsworth associated, as if they belonged to the same order; but this confusion must have arisen from the ignorance of the writings of one or the other. No two writers can be more unlike. Boz, it is true, has descended into the haunts of guilt and depravity; but he has brought back no foul airs with him, and, by a marvelous delicacy of perceptions and treatment, has described vice faithfully, without shocking the moral sense of his readers by the coarseness of the portraiture. … [T]here is not a gleam [of Dickens’s observations] to be detected in the tea-tray pictures of “Jack Sheppard”: besides, there is a cordial humour, a cheerful humanity, and a healthy purpose that we look for in vain throughout the pages of Mr. Ainsworth.13

Oliver Twist was to be distinguished from other similar novels, and particularly from Jack Sheppard, because of the ways in which it appealed to the moral sensibilities of its reader: “natural sentiment,” “moral sense.” How it did this is unclear from these descriptions—“cheerful humanity” and “healthy purpose” are terms that offer little analytical precision—but the general implications seem clear enough: Oliver Twist is more appealing to its readers’ moral feelings because it has other, “healthier,” focuses than crime alone.

So, according to the novel’s reviewers, our “moral sense” tells us that Oliver Twist might feature crime, but unlike Jack Sheppard, crime is not the novel’s subject. Only the most “confused” or “ignorant” reader could mistake it for a novel about crime. In fact, what a survey of the discourse surrounding Newgate novels makes clear is how debated this question of subject matter actually was. There are a number of rather easy generalizations that could be made about Victorian moral reactions to novels about crime; yet these are overgeneralizations in no small part because they skim over how difficult—then, as now—it is to say what it means for a novel to be “about” anything.

In this chapter, I will look at the way in which morals and intuition come together around that tricky formal question of subject matter. This topic is a difficult one to discuss in any way but the most naive. The best definition for the term would probably be the one that Boris Tomashevsky offers for “theme”: “The idea expressed by the theme is the idea that summarizes and unifies the verbal material in the work. … The development of a work is a process of diversification unified by a single theme.”14 Unfortunately, Tomashevsky does not offer much analytic method for determining what the theme of a particular novel might be. In the years since Russian formalism, there has been little development in the area, and our critical language remains somewhat impoverished. This critical aporia makes it particularly difficult to talk usefully about questions of moral praise and censure in novel history. To take just one famous example, the central issue in the Madame Bovary obscenity trial was whether the novel was about Emma’s sexual activities or instead just featured them as a way of focusing on a moral lesson.15 The moral critique of a novel, in other words, often comes down to the question of whether the novel is about the characters and actions it depicts, or whether its subject is more properly expressed by narrative structure: that is, the logic relating actions to their results, and characters to their punishments and rewards. And what we will see is that the “moral sense” that separates Oliver Twist from Jack Sheppard and the rest—that makes it a crime novel not about crime—is indeed based in the experience of the novel’s narrative.

These formal elements that helped Oliver Twist win the moral debate are, as we shall see, many of those very elements that make the novel seem so familiar to us today. It is not coincidental, in other words, that narrative and moral intuition come together in the one novel that somehow remains recognizably “Victorian”—while the other Newgate novels have become museum pieces. The “high point” of the Newgate genre, as Hollingsworth called it, would also be an endpoint. The Monthly Chronicle wrote in February 1840, while London was still in the grips of “the Jack Sheppard mania,” that Ainsworth’s novel “has had no imitators—that it stands utterly alone—and that, whatever evils of another kind it may have produced, it has not inoculated our current literature.”16 In one year, Jack Sheppard had gone from being the most visible “bad book” of an entire “bad group of books” to being “utterly alone.” Wishful thinking at the time it was written, this claim was nonetheless prescient. After 1840, British novels featuring prominent criminal characters became increasingly fewer and farther between. And today, with that one very pointed exception, the Newgate novels, and their authors, have all but disappeared from the nineteenth-century canon.

That Dickens’s novel can be offered, almost two centuries later, as a synecdoche for an unread group, suggests that it is somehow distinct from the larger subgenre it is claimed to encompass. Hollingsworth writes, “What firmly draws the Newgate novels together is that most of them met firm opposition on the ground of morality or taste. … We are dealing with a school defined by its contemporary critics” (14). The continued acceptability of Oliver Twist throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and into our own, indicates that Dickens’s novel managed to escape the critical censure that drove Bulwer to other genres and cast a long shadow over Ainsworth’s career. Oliver Twist survives not as a Newgate novel but rather as a recognizable Victorian novel that represents some elements of the Newgate subgenre. Oliver manages to escape the Newgate genre, while Jack Sheppard, who escaped three times from Newgate Prison itself, fails.

The controversy at the moment of birth of the Victorian novel, then, is a moment where the formal and the moral cross, and it will allow us to understand better the moral principles that came to inform Victorian novelistic practice. The topic of subject matter—of whether a novel was really about crime or just depicted crime—lay at the heart of the Newgate novel controversy. But this concern went beyond just counting up how many crimes or criminals were in a novel. Rather, in a more complicated way, the loudest voices in the controversy turned again and again to the idea that what a novel was really about was not so much what was in the text, as what it was that kept a reader reading. But how can you define such a nebulous motivation? In what follows, I will suggest that there were specific narrative techniques that became central thematics. First, I will look at Oliver Twist, in order to show how the novel’s subject matter is tied up not only in the narrative question of what will happen to Oliver but also in the moral question of what should happen to Oliver. In order to be generically legible, the novel relies, at a very basic level, on the reader’s intuitive sense of the novel’s correct outcome. The next section will look at Victorian criticism more generally, and in particular the topic of “interest”: a term that Victorian critics used to describe the interplay of text and reader that I am describing. Finally, I will turn to Ainsworth’s Jack Sheppard, in order to try to offer a sketch—based on the terms developed in the previous sections—of the Newgate novel genre as a whole. Oliver Twist and Jack Sheppard embark on their different historical paths at the dawn of Victoria’s reign, at the moment of the coming into being of those literary careers and traditions by which we define the “Victorian novel.” And in the moral outcry against the Newgate novel, we can see the beginnings of the connections of the formal and the moral, which continue to define the Victorian novel for us today.

THE FORM OF INTUITION: OLIVER TWIST

One way to address the question of what Oliver Twist might be about—crime, or the progress past crime—would be to ask which characters it is about. Those Victorian critics who saw the novel as being a novel about crime viewed the criminal characters as, intentionally or not, the focus of the novel. Thus, it is not surprising to see Thackeray, when he insists on the novel’s moral danger, imagining a reader who is “[b]reathless to watch all the crimes of Fagin, tenderly to deplore the errors of Nancy, to have for Bill Sykes a kind of pity and admiration, and an absolute love for the society of the Dodger.”17 Notable here is the fact that Thackeray does not even find it necessary to suggest that Oliver is an unimportant character; he simply omits him from his discussion of the novel altogether. As for the criminal characters that he lists, he does not seem to find it interesting that three of them end up dead, and the other deported. Such endings, it would seem, have little impact on the reader’s understanding of the novel. In this sense, Thackeray’s view of the novel shows a striking lack of interest in any sort of narrative meaning. The description he offers of Fagin in a different context is telling. Fagin is “a clever actor,” and the audience always receives “a knowing wink from the old man’s eye”; he is “a clever portrait … a mask.”18 Such insistence on Dickens’s “cleverness” is intended as a jab at the realism of the author’s depiction, no doubt, but it also serves to highlight the lack of diachronic interest that the character might possess. Fagin is frozen: a still portrait, or an actor caught breaking character to mug for the audience.

Attempts to rescue the novel from such criticism, on the other hand, tended to focus on Oliver. This is not surprising; whatever critics might say about Oliver—usually in the context of sweeping statements about Dickens’s “good” characters—it seems clear that if the novel moves away from crime, it does so by moving him away from crime. John Forster, in an 1837 review of the novel published in the Examiner, suggests that “No one can read [the novel’s opening] without feeling a strong and sudden interest in Oliver, and that interest never ceases” (581). When he expands on this unceasing interest, though, he shifts his terms slightly: “We feel as deep an interest in little Oliver’s own fate as in that of a friend we have long known and loved” (582). We are no longer interested in Oliver himself; instead our interest has become an interest in his “fate.” Furthermore, at the same time that he extends this interest forward in time, he also extends it backward: “long known and loved.” Unlike the tableau scenes of criminals that Thackeray seems to see in the novel, Forster sees, in the character of Oliver, a temporal continuity. More importantly, he sees this continuity as the reason for the reader’s investment in the novel.

This method of redeeming the novel is not particular to Forster. In the twentieth century, Steven Marcus’s insistence on the moral seriousness of the novel led him to claim that any relationship between Oliver Twist and the Newgate subgenre is “superficial and misleading.”19 His argument focuses on the Bunyanesque nature of the novel indicated by its subtitle: “The Parish Boy’s Progress.” Implicit in this claim is the fact that the novel is in fact about the progress—that is, the motion forward—of Oliver, the parish boy in question. The other characters then become backdrop, narrative elements in the forms of temptation, occurring as Oliver’s story progresses. This close connection between the other elements in the story and Oliver’s progression, Marcus argues, is why Dickens’s “intricate and elaborate plots,” and in particular the plot of Oliver Twist, should be excused from the oft-leveled charge of excess coincidence:

[W]e cannot take it as an accident that the first time that Oliver is sent out with the Dodger and Charlie, the person whom they choose to rob turns out to be the man who was the closest friend of Oliver’s father; it is no coincidence that the first time he walks out of Mr. Brownlow’s house he is recaptured by the thieves; and the fact that the house the thieves break into, again when Oliver is first sent out, happens to be his aunt’s beggars the very notion of accident. For the population of Oliver Twist consists only of persons—the wicked and the beneficent—involved with the fate of the hero. (78)

For Marcus, the novel does not rely on coincidence so much as it relies on the figure of Oliver. The presence and actions of other characters in the novels are only justified to the extent that they are connected with Oliver’s fate. Marcus’s claim, then, would be that Oliver Twist should not be grouped together with other Newgate novels because the criminal characters, as part of the novel’s larger “population,” are not the novel’s focus of interest. Instead, they only play a supporting role in a novel really about Oliver—which is to say, Oliver’s narrative.

Here, though, we come to a rather tricky—and counterintuitive—point: even if we grant that the novel is centrally concerned with Oliver’s progression, why do we assume that it is a progression away from crime? Burton M. Wheeler offers textual evidence that it was only with his decision to extend his serial piece into a novel that Dickens “decided to rescue Oliver from a representative ‘Parish Boy’s Progress,’ that is, from workhouse to criminal associates to deportation or the gallows.”20 Wheeler points to slight textual alterations that seem, in their original, to bear out this claim.21 Even in the revised version, though, some moments in the early chapters remain ambiguous. After the chestnut scene in which Oliver asks for more, a Mr. Limbkins declares, “That boy will be hung. … I know that boy will be hung.”22 When the sentiment is repeated at the chapter’s end, the narrator offers the following: “As I purpose to show in the sequel whether [Mr. Limbkins] was right or not, I should perhaps mar the interest of the narrative … if I ventured to hint, just yet, whether the life of Oliver Twist had this violent termination or no” (15). It is difficult not to read this as coyness on Dickens’s part—in large part because it is difficult to imagine reading the novel unaware of its outcome—but the evidence indicates that when this chapter was written, the trajectory of the “life of Oliver Twist” was, at the very least, an open question.

A good point of comparison here—both in terms of generic convention and direct influence—would be Bulwer’s 1830 Paul Clifford, understood at the time as the first Newgate novel, and still, while Dickens was writing, the representative work of the genre.23 Paul Clifford attacked the criminal justice system by arguing that it was punishment that in fact produced criminals. As Bulwer put it in an 1840 preface, the novel sought to draw attention to both “vicious prison discipline and a sanguinary criminal code”: “the habit of corrupting the boy by the very punishment that ought to redeem him, and then hanging the man, at the first occasion, as the easiest way of getting rid of our own blunders.”24 It was most likely this ostensible moral purpose that Dickens admired in the novel, though he at the same time maintained some distance. In the 1841 preface to Oliver Twist in which he defends himself against Thackeray’s criticisms, Dickens invokes “Sir Edward Bulwer’s admirable and most powerful novel of Paul Clifford” along with the Beggar’s Opera as works that depict the underworld but have “other, wider, and higher aims” (liv).25 In a scene from Bulwer’s novel that seems to have provided a model for Oliver’s mistaken arrest, a still relatively innocent Paul is sent to prison when his companion steals an esteemed lawyer’s watch on the street (75).26 Sent to prison to pick oakum, Paul falls in with criminal acquaintances and thus begins his life of crime. Picking oakum is also the task Mr. Limbkins assigns to Oliver when he arrives at the workhouse. Such generic similarities did not go unnoticed. Punch, in 1841, offered a “recipe” for a “startling romance,” after the fashion of Jack Sheppard:

Take a small boy, charity, factory, carpenter’s apprentice, or otherwise as occasion may serve—stew him down in vice—garnish largely with oaths and flash songs—boil him in a cauldron of crime and improbabilities. Season equally with good and bad qualities—infuse petty larceny, affection, benevolence, and burglary, honour and house-breaking, amiability and arson—boil all gently. Stew down a mad mother—a gang of robbers—several pistols—a bloody knife. Serve up with a couple of murders—and season with a hanging-match.

N.B. Alter the ingredients to a beadle and a workhouse—the scenes may be the same, but the whole flavour of vice will be lost, and the boy will turn out a perfect pattern.—Strongly recommended for weak stomachs.27

There is a sneer in the reference to Oliver at the end, to be sure, but there is also some insight into the effect of the novel. Whatever the reason that Oliver’s path changes course, the end result is that the novel loses its “flavour of vice.”

But when does it lose this “flavour”? Or, what comes to the same thing, when does it become apparent that Oliver will not become a criminal? Biography can be of some assistance here. In June 1837, Dickens’s sister-in-law Mary Hogarth died, an event that plunged Dickens into grief, and left him—for the first and last time—unable to write. The June number of Oliver Twist did not appear in Bentley’s. When the number, containing chapters nine, ten, and eleven, did appear a month later in July, the novel had started to move in a different direction. For it is in the tenth chapter that Mr. Brownlow, who will be Oliver’s benefactor, and ultimately solve the mystery of his birth, first appears, and it is at the end of the eleventh chapter that Brownlow takes Oliver home with him. This marks a significant moment, for Brownlow is the first character to enter the novel from outside what D. A. Miller calls the “world of delinquency”: made up of the workhouse, Fagin’s lair, and the criminal justice system.28 Generally speaking, he is the first character who is not involved in the corrupting process that Bulwer describes—a pattern Dickens, seemingly, had been following.29

It is as a direct result of Brownlow’s entry into the novel that Oliver is able to cross over from the world of crime and the workhouse to the middle-class, domestic world. Such crossing between the two worlds is quite rare, because the novel keeps these separate worlds tightly segregated from one another. For Oliver to go from Fagin’s clutches to Brownlow’s protection, for example, he cannot simply walk (109). He seemingly cannot even have agency in crossing. He must be taken by force, first carried by Brownlow while unconscious, and then, upon returning, carried kicking and screaming by Nancy and Sikes. Similarly, when Brownlow later brings Monks to his house to answer for his plots against Oliver, it is only with the help of two unnamed enforcers. By contrast, both Oliver and, later, Noah Claypole, are able to walk directly from the world of the workhouse—what Miller classifies as part of the world of delinquency—to Fagin’s lair. Nancy’s attempt to come in contact with the other world, finally, will lead to her death. If the novel has one significant shift in its narrative sense, then, it most likely comes at this moment. Forster’s comment on the interest we feel in “Oliver’s fate,” for example, appears in response to the following number.

The tendency here, I think, is to see this moment as a confirmation that Oliver has always been good, and therefore as the fulfillment of a Lukácsian “poetic necessity.” But this interpretation seems to rest on an unjustified teleology, which explains away a significant shift in narrative trajectory by claiming that the shift is, itself, the natural outcome of a narrative trajectory. We should be careful not to assume, in other words, that the reason the novel shifts into a redemption narrative is that it had always been tending toward redemption. Such retrospective reading is subtly present, I think, in even the most sophisticated analyses of the novel. Miller, discussing Brownlow’s disciplining desire to know everything about Oliver’s past, writes that it is “clear what Oliver’s story … is going to do: it will entitle him to … a full integration into middle-class respectability.”30 What Miller is referring to here, in “Oliver’s story,” is of course, the detailing of events of Oliver’s life, up to and including the present moment. The story of Oliver Twist—the novel, in italics—is also the story of Oliver Twist, the boy. We see this later, when Oliver is asked, again, to tell his story to Dr. Losborne and the Maylies. What must be the longest uninterrupted speech that Oliver delivers in the novel—if not in his life—is described by the narrator without direct quotation: “The conference was a long one; for Oliver told them all his simple history. … It was a solemn thing, to hear, in a darkened room, the feeble voice of the sick child recounting a weary catalogue of evils and calamities which hard men had brought upon him” (233). By withholding Oliver’s direct discourse, the narrator leaves the reader no choice but to assume that Oliver has given the same account to his protectors as the narrator has given to us. Miller’s point about what Oliver’s story will make “clear” to his domestic, middle-class listeners also seems to be a point about what this novel has already made clear to us: domestic, middle-class readers. This connection between us, as readers, and Brownlow makes sense, since Brownlow is a reader too: he first encounters Oliver while he is at a bookseller’s stall, “reading away, as hard as if he were in his elbow-chair, in his own study” (73). And if Brownlow had read the novel that we have been reading, or so Miller suggests, then he would clearly see where it is heading. As I have been arguing, though, before Brownlow takes Oliver to his house, there has been no clear direction, or, if there is one, it tends toward the gallows. Brownlow does not take Oliver home in accordance with a redemption narrative—he produces that narrative. To rely on our sense of structural necessity to explain his actions, then, would be to reverse the order of operations.

Rather than occurring as a result of what has come before, Brownlow’s action brings something new into the novel; and it is here, in what is new, that the novel has to rely in a fundamental way on intuition. Brownlow, after all, has never seen Oliver before. Yet his decision to take him home with him is not simply benevolence; the novel suggests that he would not have taken just any orphan boy. As he tells Oliver, “I feel strongly disposed to trust you …, and I am more interested in your behalf than I can well account for, even to myself” (104). And indeed, this seems to fit with the novel’s general emphasis on the trustworthiness of Oliver’s physiognomy. We have already heard, from Brownlow’s point of view, that “it was impossible to doubt [Oliver]; there was truth in every one of its thin and sharpened lineaments” (90). Later on, a similar moment will occur when Rose Maylie not only understands his virtue but manages to intuit almost his entire story on sight: “think that he may never have known a mother’s love, or the comfort of a home; and that ill-usage and blows, or the want of bread, may have driven him to herd with men who have forced him to guilt” (231). Yet this later moment is of a different sort, because it occurs well after Oliver’s first introduction into the domestic sphere, with the implications of the genealogical story—on which I will have more to say shortly—already underlying the narrative. When his goodness appears obvious to Rose, it is, for the most part, already obvious to the reader as well. Thus her intuition is a confirmation of sorts. Brownlow’s intuition, on the other hand, actually plays a motivating role in the narrative; for it is due to this intuition that he moves not only Oliver, but also the novel, into the domestic sphere.

This intuition, though, should not be understood simply as a clumsy contrivance or deus ex machina. There is a motivation, even though Brownlow has never seen Oliver before. It is just not a motivation that is based in Oliver’s story, as we have known it up until this point. Here is the moment when Brownlow first gets a good look at Oliver:

“There is something in that boy’s face,” said the old gentleman to himself as he walked slowly away, tapping his chin with the cover of the book, in a thoughtful manner; “something that touches and interests me. Can he be innocent? He looked like—Bye the bye,” exclaimed the old gentleman, halting very abruptly, and staring up into the sky, “Bless my soul!—where have I seen something like that look before?” (77)

Here the genealogical story, which will be developed in the novel’s next chapter, and finally revealed in full in chapter forty-nine, enters the novel.31 Oliver is an orphan, of course, and we are told that he looks like someone, even if we do not know whom. This seems to be a clear sign of some sort of familial connection, though not necessarily of parentage. It can be startling, given what we know of the novel, to look back and realize that this is the first time that Oliver’s genealogy has even been treated as an enigma, much less an enigma that demanded a solution. Indeed, as the opening chapter indicates, Oliver’s predicament is common enough to be a well-defined social situation: Oliver “fell into his place at once—a parish child—the orphan of the workhouse—the humble half-starved drudge—to be cuffed and buffeted through the world—despised by all, and pitied by none” (3). Dickens’s quick succession through these phases, from “parish child” to “despised by all,” depends on the familiarity of the figure of the orphaned pauper. And since it is so familiar, there is no expectation that more need be said on this front. Here, though, Brownlow not only articulates the enigma and starts to offer an answer (“He looked like—”) but also cuts it off, and withholds the resolution (“Bye the bye”). Brownlow’s felt motivation to bring Oliver over to the novel’s other world is introduced with a new formal device in the novel: what Barthes would call the hermeneutic code, or what we might call, more simply, “suspense”—using Caroline Levine’s broad definition of the term as “conspicuously withholding crucial pieces of knowledge” from the reader.32 Here Brownlow’s characteristic “absentmindedness” serves the purpose of the narrative, by holding this information back.

But that same absentmindedness—or, really, any sort of mindedness—also serves a second important purpose: it locates the source for this information elsewhere than in the events described in the novel. This is the first time in the novel that we are given access to private speech or recorded thought that indicates the existence of a knowledge of people and events that we, and Oliver, do not know. It is not surprising—in light of the lessons of Marxist and new historical criticism—that the introduction of the middle-class domestic world should bring with it the internal space of private subjectivity.33 What I want to stress here, though, is that this glance inward is also a glance away from the world of the novel. Brownlow is drawing his intuitions from places and scenes to which the novel’s reader has no access. As he tries to place Oliver’s face, he retreats to his memory and imagination: comparing Oliver to a “vast amphitheatre of faces.”: “There were the faces of friends, and foes, and of many that had been almost strangers peering intrusively from the crowd; there were the faces of young and blooming girls that were now old women” (77). Part of the function of these lines, of course, is personification: hammering home the point that Brownlow is old, is kindhearted, has suffered loss. At the same time, though, the lines makes it clear that whatever the nature of the genealogical plot will be, its possible cast of characters is much larger than that which is presented to us through the narration. Oliver’s story, as Miller describes it, is inseparable from the accounts depicted in the novel. The genealogical story is a separate story, with its own timeline and characters. And it is based on this story—the existence of which he senses, even as the specifics elude him—that Brownlow first intuits Oliver’s goodness.

To sum up, then: the chain of events that have taken place in the novel’s Newgate plot—that is, in the world of the workhouse and criminals—do not in themselves make it clear that Oliver belongs in the domestic plot. Dickens instead introduces another story, which he vaguely hints at but does not elucidate, and uses this story as the basis of Brownlow’s intuition. The one thing that we are given is that this story is, in some way, connected with Oliver’s genealogy. As the novel continues, this underlying story comes to provide a logic of explanation for nearly everything that happens. Previously, Fagin’s desire to corrupt Oliver had been explained by the fact that an innocent-looking child would make a good pickpocket, and Fagin had sought to retrieve Oliver from the police so that he could not “peach” about Fagin’s organization. Starting in chapter twenty-six, though, the novel shows that Fagin’s interest in Oliver to be due to payment from a mysterious figure. Along with this character, the novel also introduces groups of unknown characters, discussing a locket that we have never seen. The novel makes it clear, in other words, that the events that it is showing are determined by a story that its readers cannot fully access, except through its textual manifestations. The chapter titles self-consciously remind the reader of this: the title of the locket chapter explains that its contents “may be found of importance in this history”; the chapter describing Monks’s first visit to Fagin advertises, “In which, a mysterious character appears upon the scene; and many things, inseparable from this history, are done and performed.” From the moment of the introduction of the genealogical story, then, the novel draws attention to the fact that its events are determined by an underlying rationale, even as the specifics of this rationale are kept hidden.

Here, though, we are faced with what I referred to in the previous chapter as the “antinomy of narrative theory”: the fact that the underlying story determines the narrative without pre-existing it. In the case of Oliver Twist, it is this genealogical story that is not actually there—at least not until chapter forty-nine, when Brownlow interrogates Monk and records the story into the textual narrative. Up until that point, the novel repeatedly asserts the existence of a determining logic but does not say what it is. In a rigorous sense, then, the genealogical story does not exist. This is true in a rather more practical sense as well: in March 1838, while the chapters mentioned earlier—the introduction of the locket as a MacGuffin,34 Monks’s machinations—were being published, Dickens famously wrote in a letter that no one would be able to produce a premature stage version, because “nobody can have heard what I mean to do with the different characters in the end, inasmuch as at present I don’t quite know myself.”35 Though the novel insists on the existence of this underlying story, it only exists for the reader the same way it exists for Brownlow—as an internally felt certainty that there is a way that events should be occurring, that still only takes the form of nebulous intuition.

As soon as Brownlow begins to figure out the specifics of the story, we are no longer allowed access to his thoughts. The moment when Brownlow’s intuition is proven correct comes when he has taken Oliver to his house. There, he sees Oliver sitting under a painting: “he pointed hastily to the picture over Oliver’s head, and then to the boy’s face. There was its living copy” (90). At this point, though, in a rather clumsy contrivance Oliver faints away from the surprise of it all, and Dickens offers a self-conscious “meanwhile” to deflect the reader away from Brownlow’s discovery:

Oliver knew not the cause of this sudden exclamation; for, not being strong enough to bear the start it gave him, he fainted away. A weakness on his part, which affords the narrative an opportunity of relieving the reader from suspense, in behalf of the two young pupils [the Dodger and Charley Bates] of the Merry Old Gentleman. (91)

Because Oliver has fainted, then, Dickens does not even follow Brownlow’s finger to the wall, leaving us in a similar position to the one that Brownlow was in earlier: Oliver looks like—someone. What Dickens has done here, effectively, is to shift the onus of intuition from Brownlow to the reader. We know now that there is a genealogical story, which is producing the effects we see in the novel. But we don’t know the specifics of that story. The narrator’s claim, then, that he is “relieving the reader from suspense,” is more than a little disingenuous, since it comes in the context of explicitly holding knowledge back from the reader. What it does indicate, however, is that the reader’s engagement with the novel is now based on suspense: the belief that there is something to be known, which we do not yet know. The fact that the novel seems to know this, and to dole it out and withhold it, is what gives Oliver’s narrative its sense of definite direction.

I started by suggesting that Oliver Twist was considered exempt from the Newgate genre insofar as the novel was considered to be about Oliver. What that means, though, is not so much that the novel is about Oliver at any one point in time but rather about his progress through, and away from, crime. In contrast, for Thackeray to see the novel as being not about Oliver, he has to see it not as a progression but rather as a static portrait. Fagin, Nancy, and Sikes are, for Thackeray, not characters whose deaths are ultimately important to how we perceive them. The moral reading of the novel, then, requires that a specific narrative trajectory be part of Oliver’s characterization. As I have been trying to suggest, that narrative trajectory first enters the novel with Brownlow and takes the form of a moral intuition based on, and drawing from, the genealogy plot: from the belief that the sequence of events that we are reading has a specific direction, tending toward Oliver’s final acceptance into middle-class society. In generic terms, we can also see the introduction of this underlying story as the move away from Newgate fiction, from novels about crime and criminals.

My argument, with its emphasis on the intuition of the direction of the novel’s narrative, may seem to locate its object halfway between the reader and the text. For, what ultimately allows the novel its exemption in the Newgate novel controversy is also what gives it its familiar narrative form, the structured plot based on the intertwining of suspense and actions: suspense only being created insofar as the actions occur in the novel, the actions having meaning and coherence based on the determining knowledge that the reader must assume underwrites the text. It is this relation that produces the “ought” in Oliver Twist. Recall Harpham’s formulation of the “ethical” dimension of reading: “Readers … construct the text freely but construct it as the law of the text.”36 The reader follows what seems like the underlying structure of the text while at the same time supplying that structure—building it from a mixture of textual clues and intertextual generic knowledge. Harpham is careful to keep his general formulation separate from any specific ethical content; this allows the “law of the text” to be specific to whichever text happens to be under consideration. In the case of Oliver Twist, though, we do not need to abstract so far, since its representations of vice were part of a debate situated not only in abstract normativity but in specific Victorian norms: What may be represented? What should we read? What I have been trying to suggest is that the answer to these questions, in Oliver Twist, was not simply about what appeared in the text. Rather, it was about how the text made the reader feel, at an intuitive level, in relation to what was depicted. Not only the underlying narrative structure but also the reader’s role in the creation of that narrative structure determined the moral quality of the novel.

INTERESTING CRIMINALS: THACKERAY

The moral quality of Oliver Twist, then, can be traced back to the reader’s role in the production of the novel’s narrative trajectory. In this section, I would like to turn to the critical discourse that surrounded Newgate novels—the sum total of which we usually now refer to as the “Newgate novel controversy”—to show that Victorian critics took a consistent, if somewhat unconsidered, approach to the issue of novelistic morality, emphasizing the interaction between the novel and the reader. In the same way that critics located Oliver Twist’s moral quality in the way it oriented its reader toward an ending, so the Newgate novel controversy, in general, was not about what represented elements were in the novels so much as what methods the novels used to keep their readers reading—what, to use the term that critics of the time used, made the novels “interesting.” I will be focusing particularly on Thackeray, who was one of the most vocal and consistent critics throughout the period.

First, though, we should address the reason most often given for Victorians’ strong reaction to novels about crime: the fear of emulation. Literary history usually offers one case in particular as an example of this fear: the confession and execution of Benjamin François Courvoisier. Some background is in order: on May 5, 1840, the elderly Lord William Russell was murdered by Courvoisier, his valet. When the Times published his confession on June 25, it mentioned as well that, under questioning from the sheriff, Courvoisier had asked him “to let it be known to the world, that the idea was first suggested to him by reading and seeing the performance of Jack Sheppard.”37 The book, he said, had been lent to him by another servant, and “he lamented that he had ever seen it.” Ainsworth then wrote a letter to the newspaper claiming that he had investigated the matter and found that “The wretched man declared he had neither read the work in question nor made any such statement.”38 Most available evidence indicates that Ainsworth was closer to the truth, but that did not prevent parliamentary handwringing about the novel, or the eventual refusal on the mayor’s part to grant any new licenses for plays bearing the name Jack Sheppard.39

In the journals and reviews of the time, though, we actually find considerable reticence to assign such immediate influence on Courvoisier to Ainsworth’s novel. No less than many modern critics of cultural productions that glamorize violence or crime, the critics of the time had an ambivalent, if not equivocal, relation to the question of moral influence. In “Going to See a Man Hanged,” his magisterial denunciation of the death penalty, Thackeray describes moment by moment the scene of Courvoisier’s public execution. Yet he never once mentions Ainsworth or Jack Sheppard. This omission is particularly odd, since contemporary novels do play a part in his discussion. Noticing a prostitute “that Cruikshank and Boz might have taken as a study for Nancy,” he concludes that she is quite unlike the portrayal of such women “in late fashionable novels.”40 Rather than point to the novel that had been tied in public discussions directly to the crime, Thackeray instead makes vague jabs at Dickens’s novelistic verisimilitude. After insisting, famously, that since Dickens would not be able to “paint the whole portrait” of a prostitute, he “had better leave the picture alone altogether,” Thackeray moves even further into generalization to make his final claim: “The new French literature is essentially false and worthless from this very error—the writers are giving us favourable pictures of monsters … (to say nothing of decency or morality)” (155). Eliding the very novel attached to the case he was seeing, Thackeray turns instead to Dickens. And then, when he turns to the possibility of indecency or immorality, he turns to an unnamed body of “French literature”—the ultimate point, furthermore, in parentheses. At what should have been—and was, by many historical accounts, perceived as—the proving grounds of Newgate novels’ pernicious effects on public morality, Thackeray’s interest seems to be drawn more to a discussion of selection of details. In other words, the discussion is not one of whether it is permissible to portray crime, but how one can portray crime without falling into error. If novelists cannot “paint the whole picture,” that is a result of public morals, but it implies that painting the whole picture—even of criminals—would have at least artistic validity.

The depiction of vice, then, was not simply seen as morally pernicious. Thackeray may, at the time, have believed that public morals made it impossible to present crime in any other fashion, but this conclusion was largely his own. Other critical voices tried to distinguish between a novel that simply depicted vice and one that was about vice. In the Athenaeum review of Jack Sheppard mentioned earlier, for example, we find that the novel was not criticized simply for depicting vice. While casting Jack Sheppard as a “bad book,” the review is at pains to point out that tales of criminals could be morally valuable. In what becomes a critical commonplace in reviewing the novel,41 the Athenaeum draws a comparison between Ainsworth’s novel and two famous eighteenth-century presentations of its principal characters: Fielding’s Jonathan Wild and Gay’s Beggar’s Opera. These eighteenth-century works, we are told, had a moral plan behind their depictions: satirizing the economically and politically “great,” to use Fielding’s term, by showing their similarity to petty criminals.42 What makes Jack Sheppard a “bad book” is the absence of any such purpose. It lacks a moral message and depends solely on its depiction of crime to engage its readers. In Ainsworth’s novel, according to the Athenaeum, crime “is the one source of every interesting situation.” This whole “bad class of books” is bad, then, not because of the depiction of crime but because of the way it relies on crime alone to produce the novel’s interest.

This term, “interest,” is nowhere explicitly defined, though, as we shall see, it recurs with startling regularity throughout discussions of Newgate novels. The discussion from the Athenaeum offers a useful context for understanding the term’s usage. Novels that depict vice can have, in the terminology of modern American obscenity legislation, “redeeming social importance.” This, for Victorian critics, was the value of a Gay or a Fielding. A novel like Jack Sheppard, on the other hand, simply presented crime for its own sake. This distinction is familiar enough, though notoriously difficult to pin down in a specific case. “Interest” becomes important in Victorian criticism specifically as a way to make clear what the central element of a novel is. Tomashevsky, as I have mentioned, offers an account of theme that correlates loosely with the idea of subject matter. But as Tomashevsky points out, a theme in a novel—crime, for example—is not by itself enough to structure a literary work. In addition, “interest must also be maintained, attention stimulated.”43 Something goes from being a theme of a book to an indispensable element of the book through focusing and maintaining the reader’s interest.

If we turn back to Oliver Twist, we can see that what I have been describing as readerly engagement, or the production of intuition, can also be understood as “interest.” When Brownlow first appears, he sees something in Oliver’s face “that touches and interests” him; he later tells Oliver that he is “interested in [his] behalf.” Or, as Forster similarly wrote: “No one can read [the novel’s opening] without feeling a strong and sudden interest in Oliver, and that interest never ceases.” Building on the discussion of narrative intuition in the previous chapter, we can extend Tomashevsky’s claim that “the function of sympathy is primarily to direct interest and maintain attention.”44 Sympathy, in its various forms, can do this sort of work, and often did in Victorian and post-Victorian fiction. Yet sympathy is, in its novelistic form, a largely synchronic operation, operating through metaphors of the visual, as Audrey Jaffe argues when she points out “the powerful interplay between the specular quality of Victorian sympathy and the spectatorial character of Victorian culture.”45 There seems to be something different operating in the sort of diachronic narrative interest that we see with Oliver. Sympathetic representations can produce interest, but just as we should not assume that all criticism of Newgate novels was based on a fear of emulation, so we should not assume that interest in a character—criminal or otherwise—was necessarily based on sympathetic identification.46

As with the production of the genealogical plot in Oliver Twist, there is a certain ambiguity, in both Victorian and twentieth-century criticism, around who is actually responsible for the generation of interest. If reader’s interest defines the subject of the novel, then what produces the interest? Tomashevsky strikes a middle ground, claiming that, though the reader’s emotional reaction is essential to his theory, “this emotional coloration is inherent in the work; it is not imposed by the reader” (65). This qualification may contain a certain predictable formalism—locating meaning ultimately in the work itself—but it is not particularly different from the ideas put forward by Victorian critics. A novel’s interest was not presented as an inherent quality, it is true; the reader’s reaction was what was ultimately important. But the way in which a novel engaged the interest of the reader, as we shall see, would be presented as the novelist’s responsibility.

The reader’s interest thus plays a complicated role: at once the measuring stick of a novel’s moral worth, and almost thoroughly under the control of the novelist. Thackeray’s Catherine offers a usefully explicit rendering of these themes. This rather uneven novel was intended as a parody of Newgate conventions, one that would, in Thackeray’s words, make it impossible for the reader to “mistake virtue for vice” or “allow a single sentiment of pity or admiration to enter his bosom for any character in the piece.”47 Perhaps suspicious of his own sneaking affection for his characters, Thackeray breaks from his parodic authorial voice to offer several explicit critiques. At the end of the first chapter of the parody, the author criticizes novels that depict crimes committed by virtuous characters: “if we are to be interested by rascally actions … let them be performed, not by virtuous philosophers, but by rascals” (19).48 No better are those novels that do feature rascals but “create interest by making their rascals perform virtuous actions.” “Interest” here seems to stand in for a certain sort of engagement that a reader has with a novel. Notable, though, is the fact that Thackeray’s imagined reader has little control over how his or her interest is directed. Since we cannot help but be interested by rascally actions, it is up to the author, who “creates” the interest, to make sure that such actions are performed by rascals. The creation and maintenance of a reader’s interest, we are left to infer, is at the novelist’s discretion. Discussing Dickens’s Oliver Twist in his afterword, Thackeray writes, “The power of the writer is so amazing, that the reader at once becomes his captive, and must follow him whithersoever he leads.” The result: “No man has read that remarkable tale of Oliver Twist without being interested in poor Nancy and her murderer” (132). The novelist holds such sway over the reader’s interest that “no man,” Thackeray presumably included, can help but be interested. Such interest can even be quite against the reader’s better judgment. Turning from Dickens to Ainsworth, from bad to worse, Thackeray has this to say of Jack Sheppard: “bad, ludicrous, monstrous as the idea of this book is, we read, and read, and are interested, too” (132). In a slightly later discussion of the works of Eugène Sue—we should recall that in his article on Courvoisier’s hanging, Thackeray slipped easily from a critique of Oliver Twist to one of “fashionable” French novels—almost identical language is employed: “Read we must, and in spite of ourselves; and the critic … though compelled for conscience-sake to abuse this book, is obliged honestly to confess that he has read every single word of it, and with the greatest interest, too … though we know all this is sheer folly, bad taste, and monstrous improbability, yet we continue to read to the last page.”49 Apostrophizing the reader, finally, Thackeray asks, “Do you not blush to have been interested by brutal tales of vice and blood?” (234). The danger inherent in novelistic depiction of crime and criminals is not that the reader will believe the “bad,” the “ludicrous,” or the “monstrous” to be true. Instead, even knowing the novel to be false, we—Ainsworth’s readers, Sue’s readers, all readers—cannot help but read, and we cannot help but be interested.

This is not to say, however, that “interest” is a thoroughly negative term. Instead, it is a fact of novel reading; a reader’s interest determines what a novel, in blunt terms, is about. When the Athenaeum writes that Ainsworth makes crime “the one source of every interesting situation,” the contrast is with eighteenth-century authors who, according to the logic of the review at least, derived interest from other sources. In the case of Newgate novels, there was no shortage of alternative sources of interest. Bulwer’s Paul Clifford was a political satire—early reviews and advertisements made much of its representations of royals and parliamentarians in the guise of thieves; Eugene Aram was a psychological novel; Rookwood was to be an English gothic, an attempt, as Ainsworth puts it, to write “a story in the bygone style of Mrs. Radcliffe”;50 Jack Sheppard was a historical romance. In fact, when Thackeray criticizes the novels, he takes care to point out that he is not criticizing them as a whole but only their “Newgate elements.” In any of these novelistic subgenres, a certain thematics of crime might have been acceptable, as a means to an end other than entertainment through crime alone. In each of these cases, then, the claim that the novel was actually a Newgate novel meant that its portrayal of crime went beyond mere theme and ended up overtaking the subgenre it was supposed to support. The reader’s interest came to rest, in other words, on the crime, and only on the crime.

John Forster’s review of Jack Sheppard in the Examiner—perhaps the most damning review of the novel to see print—criticizes the novel on specifically these grounds. Ainsworth starts off promisingly enough, Forster writes, with “a few spirited scenes” of historical romance, and there is hope that “the nominal hero may be … a mere background” to a better sort of novel:

Soon, however, is this illusion dissipated, and crime—bare, rascally, unmitigated, ferocious crime—becomes the idea constantly thrust before us. From that instant all of what we will call the interest of the book may be said to hang upon the gallows, and the reader finds himself suddenly launched on one undeviating and very dirty road to that pleasing and elevated object.51

Though the novel may be called Jack Sheppard, though it may feature Jack Sheppard, Forster begins the review by offering the hope that the novel might not be about Jack Sheppard. The interest of the book could have rested somewhere else: in “that sort of a picture of romance, for a correct rendering whereof Mr Ainsworth has indisputable requisites”—in other words, in historically meticulous descriptions of Jacobite intrigue. Certainly crime, and the world of Jack Sheppard and Jonathan Wild, would have played a part in such a picture, but it would not have been the source of interest. The historical verisimilitude of the romance, after the fashion of Scott, would have used crime to produce a different source of interest. Ainsworth, though, neglects this calling and uses “bare, rascally, unmitigated, ferocious crime” as an alternative to this other, better approach. Though he has a generic choice, Ainsworth’s fault lies in allowing the Newgate themes to be the source of all “the interest of the book.” A Newgate novel, in other words, is not only a novel with “Newgate themes” but rather a novel that uses those themes to keep a reader’s interest.

These alternative sources of novelistic interest, though, go beyond generic themes; they derive as well from the novel’s formal relation to narrative structure. We can glimpse this in Forster’s offhand comment that Jack Sheppard’s interest “may be said to hang upon the gallows.” The Tyburn gallows are not where the novel ends, precisely—there is a small amount afterward dealing with the noncriminal characters—but they are the end of Jack Sheppard’s story. Insofar as the novel makes clear that crime is the source of its interest, that interest ends on, or hangs upon, the gallows. Not only that, but this ending is clear “from the instant” that it is clear that the novel’s interest lies in crime. From this point forward, the rest of the novel is only an “undeviating and very dirty road” to Tyburn. This criticism of the novel suggests that, in its move to crime as its main source of interest, the novel also settles into a recognizable generic storyline, made familiar by the Newgate Calendar—or, more properly, one of the numerous collections of criminal biographies that bore that name.52 If there is a positive generic feature in these novels it is this: as Hollingsworth puts it, “a Newgate novel was one in which an important character came (or, if imaginary, might have come) out of the Newgate calendar” (14). As the parenthetical qualification suggests, this classification is not absolute, nor is it absolutely reliable. Still, to the extent that a subgenre relies on certain readerly expectations, there could be little mystery of the final outcome of a Newgate story. Newgate Calendar biographies almost always ended on the Tyburn gallows. A large part of what separates the novel that simply depicts crime—the novel that Jack Sheppard might have been—from the novel that is about crime—the novel it turned out to be—seems to lie in the way it enacts certain generic conventions of the criminal story. Thus, for Forster, it is enough to say, by way of shorthand for all of the moral problems that Ainsworth’s concentration on crime presents, that we know how the story will play out; we know its ending.

The alternative to such knowledge—the form of interest that kept a reader reading specifically through a lack of knowledge—took a form we have already seen: suspense. In an 1836 letter to his then-publisher John Macrone about his story, “The Black Veil,” Dickens writes, “I am glad you like The Black Veil. I think the title is a good one, because it is uncommon, and does not impair the interest of the story by partially explaining its main feature.”53 The “interest of the story,” by this usage, would be something ruined by an early revelation. This is hardly a peculiarity of Dickens’s phrasing; we see a nearly identical usage in a review of Charlotte Brontë’s Shirley: “while the interest of the story is generally well sustained, the dénouement is veiled with a greater tact than is usually employed in modern fictions.”54 The term, then, seems a shorthand for suspense, mystery, deferred knowledge. Of course, suspense is only sustained for so long, and deferred knowledge is ultimately conferred. So interest here displays its economic connotations as well: the promise of a narrative payoff for the time and attention invested. Victorian interest, then, appears to do what Peter Brooks has famously attributed to “narrative desire”: the desire that “carries us forward, onward, through the text.”55 Brooks’s reference to psychic drives is, as we shall see, somewhat stronger than the Victorian concept of interest. Still his terminology fits nicely with Thackeray’s description of the reader who “must follow” the novelist “whithersoever he leads.”

In the late 1860s, Alexander Bain’s Mental and Moral Science would attempt to systematize, and make physical, the notion of the “interest of the story.”56 Drawing an explicit connection between novel reading and physical excitement, Bain refers to “the mental attitude under a gradually approaching end, a condition of suspense, termed Pursuit and Plot-interest.”57 “Plot-interest” here describes more than literature alone. Any activity that requires the pursuit of some end—“combining a small amount of uncertainty with a moderate stake” (270)—will, according to Bain, produce roughly the same reaction. As his name for the phenomenon indicates, however, narrative literature enjoys certain pride of place in his system. After moving through a series of increasingly refined experiences—“the excitement of pursuit as seen in the lower animals,” “field sports,” “the occupations of industry,” “the sympathetic relationships,” and “the search after knowledge”—Bain turns to “the literature of plot, or story.” Such literature, he claims, is “the express cultivation of the attitude of suspense.” The audience of a narrative will not actually be experiencing the events described, but the mechanics of plot will make it seem as if they were:

An interesting stake, at first remote and uncertain, is brought nearer by degrees; and whenever it is visibly approaching to the decision, the hearer assumes the rapt attitude that takes him out of the subject sphere. … The entire narration in an epic poem, or romance, is conceived to an agreeable end, which is suspended by intermediate actions, and thrown into pleasing uncertainty; while minor points engage the attention and divert the pressure of the main plot. (272–73)

“Plot-interest,” then, has two elements: the promise of an “agreeable end” combined with the “pleasing uncertainty” that the end will come about. The steadily increasing proximity of the conclusion not only engages the reader but actually makes the reader momentarily forget his or her own subjective circumstances and become engaged with the narrative’s own actions and diversions.

This does not mean, though, that readers thoroughly forget themselves; and it is in this that we see why concerns about sympathy with criminal characters were different than concerns about actual emulation. We should recall Thackeray’s reticence to attribute a complete loss of control in the Courvoisier case to a reading of Jack Sheppard. In fact, he turned away from that issue entirely to make a digression—one that, absent the larger context of Courvoisier’s case, would appear to make little sense—through novelists’ one-sided presentations of criminals. The critical position, in other words, would seem to be that a reader’s engagement in a novel, even in its worst forms, does not lead to an absolute loss of subjectivity.

We see this in Bain’s language, which consistently returns to the relative moderation of the sort of interest he is describing. The reader might be “rapt” and “thrown into pleasing uncertainty,” but that uncertainty is still of a “small amount,” and the stakes are “moderate.” Plot-interest, according to Bain, must remain “within limits”: “if the stake be high, the fear of losing it will deprive the situation of the favourable stimulus of plot-interest” (269–70). Interest, then, lies in a site between critical detachment and thorough identification. This mediate position, I would argue, is crucial for our understanding of nineteenth-century descriptions of novelistic interest. As Albert Hirschman demonstrates in The Passions and the Interests, the idea of interest developed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as a “countervailing” force, which could balance the passions that were coming to be seen as the principal motivations of human action.58 Unlike concepts such as religion and rationality, which increasingly seemed ineffectual to control our baser desires, interest came to play the role of an inclination that, even while it was itself a natural inclination, exercised a moderating control over the other passions. Tracing the evolution of this concept from Machiavelli to Adam Smith and Hume, Hirschman suggests that this notion of a force at once primitive and moderating laid the philosophical groundwork for the eventual emergence and hegemony of market capitalism. Capitalism, founded on the notion of interest, became naturally virtuous: natural because it was inherent in all humans, virtuous because it resisted the animal passions that would lead a person, or a society, to ruin. Francis Hutcheson offers an evocative formulation: the impulses capable of moderating the passions take the form of the “calm desires.”59 Not desire in the sense of Brooks’s psychic drives but moderate, calm desire—this perhaps best describes the way in which Thackeray imagines the experience of novel reading.60 Readers are never imagined to thoroughly forget themselves; neither will they believe in the “ludicrous,” nor will they become criminals—even though the novel exerts some force that keeps them reading, in “captivity” to the novelist. If we are to understand Victorian moral concerns about novel reading, then, it is necessary to see that the problem with misdirected sympathy was not simply that it would lead to an enacting of crimes.

In fact, the problem with such sympathy that emerges in Thackeray’s criticism seems more related to questions of artistic honesty. Thackeray’s main dispute with Newgate novels, recurring throughout his criticism, is that they engendered in their readers “a false sympathy for the vicious and criminal.”61 The “false” part of the accusation is every bit as important as the “sympathy,” if not more so. Thackeray’s main critique of Oliver Twist, after all, stems not only from the fact that Dickens “leads” the reader to “deplore the errors of Nancy, to have for Bill Sikes a kind of pity and admiration, and an absolute love for the society of the Dodger” (132). This is only an effect of Dickens’s one-sided description of these characters. As Thackeray famously puts it, thieves and prostitutes may have their virtues, but they are “not good company for any man”: “We had better pass them by in decent silence; for, as no writer can or dare tell the whole truth concerning them, and faithfully explain their vices, there is no need to give ex-parte statements of their virtues” (132). In “Going to See a Man Hanged,” he makes a similar point. Since an author cannot present a full picture of a criminal, “he has no right to present one or two favourable points as characterising the whole; and therefore, in fact, had better leave the picture alone altogether.”62 Thackeray’s central complaint seems to be not that these authors depict criminals, or even that they cast them in a favorable light. These come as side effects of the fact that the author does not, and cannot, present the whole criminal character to the reader.

Underlying this criticism is a belief that readers are all too comfortable with their romantic preconceptions about criminals. The novelists, when they conform to such presuppositions, are only giving the readers what they want. The Athenaeum, in fact, offered this as an apology of sorts for Ainsworth, suggesting that he is a “mere caterer to public appetite”: “It is not his fault that he has fallen upon evil days, and that, like other tradesman, he must subordinate his own tastes to those of his customers” (803). Or, as Thackeray puts it, the “present popular descriptions of low life,” while “shams,” are “endlessly tickling to the reader.”63 So long as it remains in favor with readers, “the writer will not, of course, give up such a favourite mode of composition.” When it comes to crime, then, the Newgate novelists under attack give the readers what they demand; but they also give the readers what the readers already know. There is no new information about the underworld. In fact, Thackeray goes so far as to suggest that the novelists themselves know little about their subject, albeit in roundabout form: “and when we say that neither Mr. Dickens, nor Mr. Ainsworth, nor Sir Lytton Bulwer, can write about what they know not, we presume that not one of these three gentlemen will be insulted at an imputation of ignorance on a subject where knowledge is not, after all, very desirable.” So, between the novelist and the reader, there is only a repetition of familiar stereotypes and well-known caricatures.

Such depiction is a far cry from the sort of didactic depictions that Thackeray believed should be offered, if any were to be offered at all. Thus, he writes to those who enjoy Eugene Aram, Dick Turpin, or “Biss Dadsy”: “No, my dear Madam, you and your daughters have no right to admire and sympathize with any such persons, fictitious or real: you ought to be made cordially to detest, scorn, loathe, abhor, and abominate all persons of this kidney.”64 Note that the mother and daughters are not required to arrive at this outlook on their own; it is the novelist’s imperative—the novelist “ought”—to make them hate criminals, and the only way to do so is “to paint such thieves as they are.” This was what, in Thackeray’s view, figures such as Fielding, Gay, and Hogarth did, and why they therefore stood as the point of comparison to which nineteenth-century novelists would never attain. In his more thoughtful moments, Thackeray would suggest that it was that they would not be allowed to attain it, for “[s]ince the author of Tom Jones was buried, no writer of fiction among us has been permitted to depict to his utmost power a MAN. … Society will not tolerate the Natural in our art.”65 Thus, it is unclear whether Thackeray thought a moral novel concerning a criminal was even possible—a seeming equivocation that underlies both his affections for the character of Catherine and also his later insistence that Vanity Fair was a “novel without a hero.”

Equivocations aside, this description of the “right” way to depict unsavory characters and situations has a good deal in common with the focus on narrative we saw in Forster. Thackeray believed that the only moral way to portray crime and criminals was to go beyond the reader’s expectations and preconceptions. The novelist, therefore, must not only tell readers the truth but also tell them something new, something they did not already know. The only correct way to present crime would be by imparting knowledge that the author has and that the reader should have. For Thackeray in other words, if an author is to hold a character’s interest in a criminal novel, that author can only do so by capitalizing not on what the reader already knows but on what the reader does not know. Recall that the central formal move in orienting Oliver Twist away from crime was the introduction of an explicitly withheld backstory. Just as Forster criticized Jack Sheppard for defaulting to a generic structure that the readers already know—and, implicitly, moving away from one whose source of interest would be less obvious—Thackeray holds out the possibility that even criminal novels could be read morally, if only readers were interested by the promise of something unknown. He might not have counted Oliver Twist among this list, but his critical ideas help to suggest why others did, and why we still do today.

WHEN YOU KNOW WHAT’S GOING TO HAPPEN: JACK SHEPPARD

Reading novelized accounts of real people and events can be an oddly powerless experience. History has already happened; Moscow was evacuated and burning when Napoleon arrived. I know that in a different way than I know that Jane Eyre married Rochester. Both are immutable, but somehow, as a reader, I feel involved in the re-creation of Jane’s plot. This time, she hasn’t married him yet. (And maybe, just this one time, Tess will live.)66 When reading novels about historical figures, though, that involvement feels a good deal more limited. Stephen Jarvis’s 2015 Death and Mr. Pickwick, to take one recent example, spends its first five hundred pages or so largely focused on Robert Seymour, Pickwick’s original illustrator. I know relatively little about Seymour, but I know he ended his life with a fowling piece, and I know the author knows it. Even if I put the book down, that death has already happened, and the book itself is a reminder of that. The book exists because Seymour died, just as War and Peace exists because Napoleon failed.

This feeling of constraint is not an issue in most realist fiction—even in most historical novels. The reason for this is simple: most of the characters we read about are fictional, and so the outcome of their story is not so fenced in by a shared historical narrative. As Lukács famously observed, in the historical novel, “world-historical” figures “can never be central characters in the action” of the historical novel. That role falls to “the ‘middling,’ merely correct and never ‘heroic’ hero.”67 These are everyday people, representative of a type. But it is precisely this typicality that allows—or even demands—fictionality. The more fictional the characters are, the more they can be understood as types as well as individuals; the more typical they are, the more the fictional representations will be recognizable. History is necessarily present in all this, but it takes its place in the background, as part of the “real” in realism, and does not take center stage. The result is that history becomes a more or less hidden element of these novels. Lukács, according to Jameson, sees realism as describing a “future of society secretly at work within its present.”68 Implicit in our understanding of realism, then, is the idea that its determining structure is hidden. This results in the paradoxical experience of relative freedom, or character autonomy, that we encounter when reading purely fictional characters: these exist to serve an underlying structure perhaps, but the conventions of realism dictate that this structure cannot be evident. Once we know that a character derives from a specific historical model, on the other hand, even if we don’t know the specifics of that history, we can’t help but read with awareness that the ending already, immutably, exists.

This helps to account for the historical fate of a novel like Jack Sheppard, which shared a moment of extreme popularity with Oliver Twist and yet has not only been largely forgotten by literary history but, somehow, feels dated. Oliver, as I’ve been discussing, bases its “plot-interest”—using Bain’s term—on something withheld: the idea that what we see is not all there is. While we read the events in the narrative, we are also aware that those events are working toward some end—toward a purpose, that is, but also toward a conclusion. This is a condition of intelligibility for most novels in the nineteenth century, a tacit answer to that unspoken question, “Why are you telling me this?” Suspense, in its broader sense, goes beyond the confines of the mystery or the potboiler. Suspense is the indication that a novel has a plan (a plot). When we read, then, we understand that we are being told about something more than the scenes and characters that the novel depicts. We are also being promised something about where the narrative is going. This describes an experience of reading that has become deeply familiar as a formal characteristic. What I have been trying to show, through the example of Oliver, is that this sort of formal familiarity—this novel that feels like a novel—was understood, in its moment, in moral terms.

Jack Sheppard, on the other hand, relies on its readers’ understanding of its own historical determining story. It refers back to its source in the confessions of the true Jack Sheppard, hanged at the Tyburn gallows. The book’s ending, Jack’s death, is the condition of its possibility. In fact, throughout, the novel suggests what its end result will be: a hanging, a confession, and the source of the novel. This circular logic—if we’re reading this book, he must have been hanged—calls attention to the fact that, unlike Oliver, Jack Sheppard is not underwritten by a separate determining story. Instead, it is determined, through a strange set of operations, by itself. The crime in the novel is a means to an end, but that end is the story itself. This is how its oddly dated feel—an example of an ephemeral subgenre instead of part of the Victorian novel tradition—relates to its narrative form, and the moral understanding of that form. The critics are quite right that Jack Sheppard is a novel that is ultimately about crime. This narrative effect comes as the result of the novel’s repeated foregrounding of the fact that its narrative is one that is not just being told but also being retold.