Be a Bee-Friendly Gardener and Consumer

The European honeybee has been a part of our global conversation for some time. Today, there are more theories on their decline than ideas for how to preserve them. The honeybee we know is not the only insect in the pollination game. In fact, many of our food and medicinal plants are wind pollinated or pollinated by native non-honey bees, flies, moths, birds, and other creatures.

But the European honeybee has become an emblem of the pollinator world. And as her health goes, so goes the health of the rest of the organisms who help plants to be fruitful. If the honeybee is the proverbial canary in the coal mine, we have reason to ask what we can do to support her ability to survive. There are many ways, be you a beekeeper open to change, a gardener who has space to plant helpful things, a responsible consumer, or a conscientious sourcing manager for a big business. How we come together to solve the problem of the honeybee will trickle down to the lesser-known pollinators and benefit us all in the long run.

As the world has become more aware of the plight of the honeybee, there has been a call for more beekeepers. Only a decade ago, our local bee club offered classes for new beekeepers. Each year the classes drew 20 to 30 people. Now, with the spread of knowledge about colony collapse and greater media attention surrounding the bee, the classes run to well over 100! This fivefold increase in our area has had many implications for the serious beekeeper and the honeybee. Equipment to maintain apiaries, a collection of hives, has become more expensive and less available, resulting in increased overhead costs for the professional beekeeper.

In Ancient Greece a law was established mandating that people keep their honeybee hives no less than 300 feet away from their neighbors’ hives. This idea was based on the very real threat to bees if every household had a hive. With any increase to the concentration of bees in a given area, there must also be a comparable increase in forage area for native pollinators so that they too can gather what they need to survive and create an appreciable harvest. We have seen detrimental effects here on our farm as more and more people in our area become beekeepers. Every time a new hobby hive is installed in our neighborhood, the amount of honey our hives produce decreases. Beekeepers need to be conscious of where their hives are located in relation to others in the area.

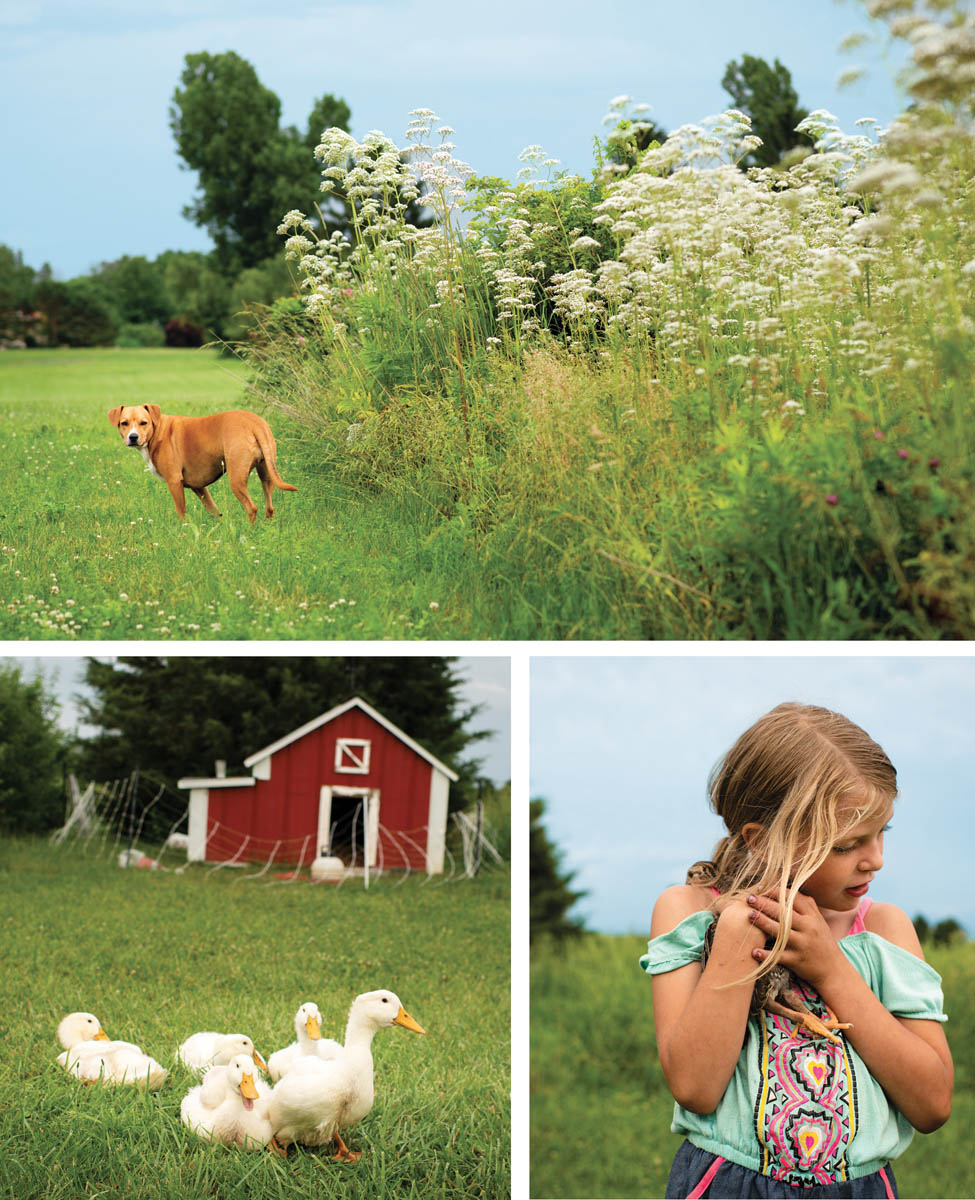

Another issue contributing to diminishing returns for bees is that many beekeepers live in a conventional farming area that focuses on grain production. For years, the United States has incentivized grain over meat production through government subsidies, which has resulted in less open grazing land. As more and more ground is taken over for grain operation, farmers have done away with windbreaks between fields. The cumulative loss of this important foraging area means that it has become more difficult for bees to find the nectar they need. The easiest and best way to help is to encourage natural areas in which bees can forage. You can convert areas of your lawn to native plantings or let acres of farmland go fallow to increase conservation.

In addition to losing grazing land and windbreaks, other agricultural changes have hurt the bees’ ability to collect pollen and nectar. The shift to genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and chemically treated seeds has reduced available food sources. Traditionally, beekeepers could expect significant honey harvests from certain crops, like soybeans. When we first started out as beekeepers, we placed hives in a woodlot surrounded by soybean plants. During our first year, the bees were very active and we had ample honey production from the new hives. However, during the second year, despite hundreds of acres of soybeans, the bees struggled to produce honey. The one variable that had changed was the farm’s switch to using GMO seeds.

Honeybees are extremely smart insects — and may be more insightful than people at times! We believe that, reacting to the altered pollen and nectar from modified soybean seeds, our bees began flying long distances across the soybean fields to find pollen and nectar that was suitable. All this travelling used up their energy stores and reduced their honey production. If you are concerned about the health of bees, you can support the use of untreated and non-GMO seeds, chemical-free farming, and organizations and groups that foster efforts to save and preserve our heirloom seed strains.

Most common landscape plants don’t provide the pollen and nectar needed to support the honeybee. A survey done in Berkeley, California, of 1,000 landscape plants found that only 128 received measurable attention from the honeybee. Today, many commercial gardening operations and retail outlets are beginning to recognize the need for bee-friendly plant options and are offering more native flowers and perennials. Consider the types of plants you choose to plant on your own property; a focus on species native to your region will help keep honeybees healthy and happy.

Perhaps one of the biggest impacts you can make to help the bees is leaving the weeds in your lawn and garden. The boost in valuable foraging and the decline in the amount of pesticide contamination can contribute far more to the health of all our pollinators than the addition of a hive to your property.

Another way you can contribute to the health of the bee is to be an informed consumer of bee products. This means being informed about the practices your local beekeeper uses to care for the bees, and understanding what it costs the bees to make the health products we enjoy. The articles we read extolling the health benefit of various hive products rarely consider what it does to the bees to produce them.

Many in the movement to help save the bees believe that we need to stop using hive products altogether, but I disagree. I think the bee is a willing part of a partnership with humans that began with the Langstroth box hive more than 160 years ago. However, we are not holding up our end of the deal. While we do need to stop consuming some products of the hive, we simply need to consume less of others. It is time for us to put the health of the bee ahead of ourselves in this beekeeping partnership.

Commercial beekeeping tends to view the hive as a storehouse of wondrous treasures waiting to be collected for our benefit. Even if a beekeeper is well intentioned and loving with her bees, it is easy to overlook the bees’ needs. Once I came to recognize that bees are a community made up of individuals, my perspective shifted. The products that we have identified as health promoting for humans have a purpose within the hive beyond that of providing goodies for us to reap.

People often ask us: What kind of honey do you produce? On our farm, we work to ensure that the honey contains everything the bee might collect from spring all the way through fall. This is done to benefit both the people buying our products and our bees. It is a very different beekeeping model from one that harvests varietals. A varietal is a honey that is made up of only one kind of nectar. For example, hives are set down next to an orange grove or a big field blooming with white clover. While that one plant is blooming the bees fly out each day and collect that specific nectar. They tend to be single-minded when there is a large bloom of one type of flower. When the flowers are done blooming the honey that has been sealed in the upper portions of the hive, called the honey supers, is collected all at once. This is how beekeepers get buckwheat, clover, orange blossom, tupelo, or any other kind of varietal honey.

In our beekeeping model, varietals are problematic because we don’t know what each one means to the bee. A human cannot necessarily see the qualities of different kinds of honeys with the naked eye or even with our tongue. The same cannot be said for the bee. To the bee, honey is not just sugar. The cells within the hive contain a complex pantry of varying levels of carbohydrates, antioxidants, proteins, and beneficial phytochemicals. When the bee collects from the flowers, she is stocking up with what the hive needs to eat a balanced diet.

We have seen firsthand that the bees know the difference between these varietals. When we leave the honey supers on into the fall, the workers are very selective in the honey they pull down into their brood chamber for the winter. They never take all of one type. It is essential that the colony have a bit of everything to make up a balanced diet. In the years before we worked our bee yards in the way we do now, we often pulled all the honey in early fall and let them go into winter with just aster honey. The hives would weaken or die off due to a disease called Nosema, a digestive disease brought on by an unbalanced diet. Now we avoid harvesting varietals because we can’t know what they may need at any given time. This approach benefits people as well! Honey made from everything harvested from spring through fall contains the best mix of vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals.

Commercially, beeswax is used as a solidifier and as a preservative. It is also widely used in body and skin care products like balms and salves. Beeswax is created by worker bees and sculpted into the familiar honeycomb shape that houses honey. Worker bees produce wax from special plates on their abdomen and they require a great deal of nectar to do it. This means that beeswax is created at the expense of honey making. It costs about 8 pounds of honey to build 1 pound of wax. Beeswax can be sustainable if it is harvested incidentally as part of the honey harvesting process and when it is kept chemical-free by the beekeeper’s practices. But when it is a commercially farmed product it becomes an undue burden on the bee.

In a commercial outfit aimed at gathering as much beeswax as possible, empty supers are added to the hive. Bees don’t like empty spaces and will fill every square inch so that they can either collect more nectar and pollen or hatch out more colony members. This requires a good deal of energy and resources, and it costs bees valuable time and honey supply to put up what they need to feed the hive. Moreover, conventional beekeeping practices routinely pollute the beeswax in the hive with toxic miticide chemicals. We believe that the beeswax is the “soil” of the hive. As with our own food, if the soil is not healthy, the things that grow in it will not be healthy either. It is essential that sustainable practices utilize methods that ensure healthy, clean beeswax inside the hive so as to maintain healthy bees and produce healthy honey.

Pollen is a complete protein source and a good source of B-complex vitamins, making it an important component in treatments for anemia, allergies, energy, mood, and other conditions. To collect pollen, beekeepers typically place a tray system at the hive entrance to alter how bees enter and leave the hive. Bees returning to the hive must move through a screen system to get to the inner recesses of the hive. While the bee is moving through the screens, the pollen sacs on the bees’ legs are shaken and the pollen falls through the screens into a collection tray for the beekeeper. The pollen is then cleaned and can be dried or used in its raw state.

Pollen is a sustainable hive product for us to use if it is shared with the bee. Bees feed their young with the pollen that they store in individual cells in the hive, and they use it to gear up for spring after the cold winter. If you look at areas of the comb where pollen and nectar are stored, you will see that the cells containing pollen create a beautiful patchwork of colors. Each color represents a different kind of pollen that the bee has collected from different plants. Some grains taste sweet, some bitter, some grassy, and each is a unique food source that is important to the hive.

Beekeepers can use pollen traps to ensure that some of each variety of pollen goes to the bee and some goes into your own collection, but it does require a lot of work to monitor the entrance and open and close the trap. It is important to use pollen with respect so as to ensure there is enough pollen in the hive and enough of a diverse mix of pollen to create a balanced diet for the bee. We can be conservative in our own use of pollen; half a teaspoon occasionally or once a day for allergies is sufficient.

Because of its antibacterial and antifungal properties, my family loves to use propolis for sore throats. We suck on it like hard candy when we feel one coming on. Propolis is an incredibly tough and sticky resin, so it is important that you never chew propolis if you like your teeth where they are! Many beekeeping books will refer to propolis as “bee glue,” but this is an oversimplification. Propolis is an amalgamation of tree resins, often from pine and poplar species, and it is used by the bees to seal up tiny openings in the hive where air or sunlight might seep in. It cements the whole hive structure together, and it can act like freshly stuck-on chewing gum when, for example, you try to lift off a hive cover in the middle of summer. While it does tend to act as a kind of glue, this quality is from a human perspective. The real purpose of propolis is to act as an external part of the immune system of both the individual bee and the community. The propolis that lines the brood chamber, inner hive walls, and walkways is antibacterial, antimicrobial, and antifungal. Studies show that reducing the amount of propolis in the hive creates a jump in the incidence of mite load and disease. Seeing this substance for what it is helps us gain an important understanding of the bee as an individual: one with a body that deserves to be whole and healthy.

Propolis is only a sustainable hive product if it is used sparingly. Propolis is not sustainable if it is farmed. As such, propolis should be harvested in limited supply. To harvest propolis commercially, the top cover of the hive is propped askew so that light and air can enter, and then a special slatted plastic screen is inserted at the top of the hive. The bees frantically divert energy away from collecting food to fill this frame up and protect themselves from intruders. Just as they get the job done, the beekeeper takes the screen, puts it in the freezer for a day to crack off the propolis, and then repeats the process. This is not a great practice. Just as we wouldn’t want to continually stimulate our own immune system to fight intruding pathogens, it is not healthy to stress the bees into continually collecting and processing propolis to protect theirs.

When harvested sustainably, a beekeeper will gather propolis incidentally while collecting honey. During honey harvest, pieces of propolis can be removed from the frames that are being harvested. However, the process can be time consuming and it requires care by the beekeeper. A few hives will produce enough propolis to last our family of four a couple years, but it won’t supply enough for commercial production.

Royal jelly is an undeniably amazing substance. There are numerous clinical studies on its ability to effect change in a multitude of degenerative diseases in humans. It is reputed to contribute to longevity and rejuvenation both internally and externally. Unfortunately, royal jelly production for human use is not sustainable for the honeybee. Royal jelly is a superfood for the bee. The amount in the diet of a young bee is what determines whether she will become a worker or a queen.

You should not let royal jelly go to waste if you come across it organically as a beekeeper — if you happen to bump open a queen cell, for example. Beyond that, it’s clear to me that we should leave this superfood be. It comes at too great of a cost for the bee to share. To harvest royal jelly on a large scale, the hive is made queen-less, removing the source of the pheromones that allow bees to feel secure. This puts the bees under an enormous amount of stress. You can actually hear a queen-less hive from a great distance if you know what to listen for. The bees keen, creating a noise of sadness and distress. In a royal jelly operation, special frames that encourage the feeding of queen bee larvae are inserted and the worker bees go into royal jelly production mode. After a few days these frames are harvested, the queen larvae destroyed, and the frames are returned to the hive to start again. I have heard that it is possible to extract some of the royal jelly and allow the larvae to live, but this is labor intensive and is not the norm.