Again that morning the sustained din of far-off artillery filled the expected hour of sunrise as darkness lifted from the American trenches. Light fog blanketed no-man’s-land—three hundred boundless yards of ripening beet plants, wheat stubble, and butchery ascending toward the German lines. Beyond the tangle of barbed wire at the unreachable crest of the hilltop, dark rooftop silhouettes of the village of Cantigny materialized against the morning’s leaden sky, framed by a horizon of piney woodlands in the distance.

Once a serene farming hamlet graced with orchards and idyllic red-roofed homes, Cantigny was now a barren maze of hollowed ruins staring back at the American lines across the forbidden plateau. Its smooth walls and rooftops had been whittled to jagged profiles by weeks of artillery fire, and though the village seemed vacant and lifeless, its stone cellars and outlying trenches were stiff with Germans.

By this, the final week of May 1918, tranquil moments on the front lines had grown rare, but for once, above the low rumble of remote shelling, no crashing of nearby artillery or chatter of machine-gun fire attended the emerging dawn. The temperature climbed out of the low fifties, but down in their trench where the bite of the night air lingered, the doughboys lay curled on the cold dirt floor or propped against the hard chalk walls, stealing what sleep they could before daybreak. They had arrived at the front lines only three hours earlier, after a long march lugging their weapons, supplies, and ammunition through crushing shellfire, and what little rest they were able to grab was surely insufficient to equip them for a new day staring down the German lines extending out the north side of the village. As the light fog and overcast sky battled the first glimmers of daylight, the sleeping figures in the trench line dressed in khaki, brown boots, wrapped leggings, and stiff, high-necked collars were lit faintly in colorless relief.

These fifty men formed 3rd Platoon, Company E, 28th Infantry Regiment of the US Army’s 1st Division, and together they held a short 150-yard stretch of the 468-mile-long Western Front—a ragged line of carnage clawed out by forty-five months of the bloodiest fighting in human history. The scene repeated itself in trenches snaking north to the English Channel and south to the Swiss border in alternating shades of French blue, Belgian navy, and British tan. The sight of American khaki in the front lines was a recent development, and though many of these doughboys had just endured their first French winter and some had been in-country nearly a year, they were still considered the new guys—the untested “Yanks.”

For twenty-five-year-old platoon sergeant Ray Milner of Titusville, Pennsylvania, who stood six feet two inches tall, keeping his steel soup-bowl helmet down below the four-and-a-half-foot top of the trench parapet took strained effort. Bent at the waist, he worked his way up and down the line quietly rustling the men, one by one, awake for their morning stand-to. With six years of Army service, Milner was a seasoned veteran when measured against the inexperienced faces he was waking up. Some were just boys, like Pvt. Homer Blevins of Fresno, California, who at seventeen was the youngest in the platoon. Most had volunteered for service in the months following America’s entry into the World War the year before, and many others had been drafted, trained, and added to the unit in the past few weeks—fresh replacements for those lost to snipers, shelling, mustard gas, or the influenza of a harsh winter that had dragged on well into spring.

It was Monday, May 27, 1918, a detail almost universally unnoticed by soldiers who had long before shed their previous life’s mental dividers of workweeks and weekends. Time passed in clusters of days marked only by greater or lesser mortal danger—ten days of cheating death in the trenches, ten days “rest” billeted in drafty barns and cottages of some anonymous French village, then ten days in “reserve” up closer to the front, where the perils of mustard gas and aerial bombardments were often worse than at the front lines. Then over again the sequence repeated, and for how long nobody knew.

Three days earlier, this monotonous cycle was finally broken as these soldiers were ordered from the front lines and trucked twelve miles away to a training area for “battle rehearsal.” As General Pershing promised six weeks before in his sendoff speech to the division officers, the 1st Division had been chosen out of the five then in France to enter that “great battle of the greatest war in history.” Rumors had since circulated among the men about when the “great battle” would finally come, and where, and which unit would get the coveted assignment.

Back at the rehearsal area, these men had learned it was their regiment—of the division’s four—ordered to retake the prize of Cantigny from the German Army. Field Order No. 18, which had descended from the typewriter of a young lieutenant colonel on the division staff, George C. Marshall, laid out the attack operation in great detail, and its thirty-nine pages of supply lists, mission assignments, and artillery barrage schedules formed the script for history. Thirteen months after President Wilson had called them to service in “the most terrible and disastrous of all wars,” and ten months after landing in France to join the Allied cause, the Americans—the “Yanks,” “Sammies,” or “doughboys”—were finally entering the fight, and the soldiers of Company E’s 3rd Platoon would be in the first attack wave going “over the top.”

The first day of battle, “J-Day” was set for Tuesday, May 28, and with two and a half days of battle-plan rehearsal complete, most of the regiment would be spending May 27, “J minus 1,” relaxing back at the training area before moving up to the front lines after dark.* But for the men of Company E there would be no rest. The four companies of their battalion had been ordered again to the front the previous night, May 26, two nights before the attack and a full day earlier than the rest of the regiment. Having taken over the front-line trenches well after midnight, some being rustled awake by Sergeant Milner had managed to squeeze in two or three hours of sleep, but many had found no rest, and fatigued by the night’s long march they were running on fumes. As dawn struggled to break, their collective hope was for a quiet twenty-four hours on the front lines before the shrill whistles blew the next morning at Zero Hour, sending them over the top and into the maelstrom of war.

* * *

Up and down its length the trench began stirring with hushed activity as soldiers sat up, buckled on their canvas web belts, hung their gas masks over their chests, and strapped on their cold steel helmets amid stretching yawns and gulps of cold coffee. Sidestepping slowly through them, moving from soldier to soldier, his stout frame buckled tight in his officer’s Sam Browne belt with holstered Colt .45 pistol, was their platoon leader, Lt. Charles Avery.

Just fourteen months earlier, Avery was a field reporter for the Kansas City Star. The United States entered the war the day before his twenty-fourth birthday, and though married with a three-year-old son, he quit his newspaper job, volunteered for Army service, and was admitted to officer school. After three months training at Fort Sheridan, Illinois, he received his commission, said good-bye to his family, shipped off to France, and was placed in charge of 3rd Platoon by March. In just his second month as platoon leader, Avery displayed an effective leadership that seemed instinctive, but it was his light, personal touch that earned the swift respect of his men. A fellow Company E officer portrayed Avery as “the fun maker” who “bubbled over with fun and scintillating wit.”

A few minutes past 5:00 a.m., as Lieutenant Avery and Sergeant Milner ensured the last of their men were awake, the calm hanging over no-man’s-land was broken by the familiar low rumble of German artillery fire. The soldiers braced at the whistles of incoming salvos, and the distant drumfire continued as the first shots hit halfway across the plateau in crashing thuds of smoke and flame. More shells followed, humming a medley of ominous tunes as enemy gunners dialed in the American lines, marching the footfall of detonations closer to Avery’s hunkered doughboys.

The blasts reached the trench in eruptions of fire and dry earth. Packed spoil of the parapet collapsed and earthen walls caved in as sheets of white flame and hot shrapnel filled the air. Lieutenant Avery scampered up and down the line checking on his soldiers, who were curled up, white-knuckled, hugging the dirt. “No such thing as a dugout in the sector, so we lay like lizards in the bottom of the trenches,” one man wrote home. “The awful explosions would come, the ground would rock, then dirt would fall in on us.” The onslaught was relentless, pounding minute after unending minute for an eternal hour, rupturing eardrums and stretching some men to their psychological breaking point. As their captain would later say of enduring such bombardments, “nothing can be done but wait, and wait, and wait.”

Steel shards and flames sliced through the cramped space, and yells and screams punctuated the thunder of shelling. The undaunted Sgt. Ray Milner, still walking up and down the line and loudly encouraging his men, was the first to fall. In a blinding flash, his standing figure was “wrapped in smoke and fire,” as Lieutenant Avery would later relay; “when the scattered mist of high-explosive fog and the uprush of earth had cleared away, the sergeant lay dead in two pieces, his trunk severed below the shoulders.”

The entire platoon was trapped in the deadly vortex, and between exploding flashes men dropped wounded and dead. Eighteen-year-old Pvt. Charles “Ollie” Shepard fell on the dirt trench floor, “killed instantly by piece of shell in back” a watching comrade would later recount. Likely hit again and buried in the shelling that continued, young Ollie’s body was never seen again. Another blast got the platoon’s youngest, Pvt. Homer Blevins, killed “instantly” when “a shell exploded alongside” him, a nearby private reported.

Surrendering to the grim lottery of shellfire, twenty-three-year-old Cpl. Chester Melton and twenty-five-year-old Pvt. Fred Turner both shriveled into fetal bundles on the trench floor. A shell hit near Private Turner, and when the smoke cleared he lay motionless in the dirt, seemingly untouched. A fellow private, Franklin Berry, found Turner lifeless, with glazed eyes fixed in a death stare. “It was more concussion than wounds that killed Turner,” Berry estimated, because “there were only a couple of scratches on him but he was as limber as a rag just shook to death from concussion.” Corporal Melton, in sad contrast, had simply disappeared. None of his comrades remembered seeing the blast that killed him, and no trace of him was ever found, leaving his carved name on the Somme American Cemetery’s tablets of the missing as the sole monument to his memory.

* * *

Three hundred yards behind them, in the captain’s small command bunker, the company’s second-in-command, Lt. Irving Wood, was worried and restless. He had been listening intently to the sounds of the bombardment, but repeated checks with the guard outside revealed no runners or messages from the front lines. The commander, Capt. Edward Johnston, was asleep, and as the roar of shelling hit full crescendo, Wood decided to wake him.

“Captain, I don’t want to wake you up about a mere bombardment, but this has been getting steadily louder, and I don’t like it.” Lieutenant Wood was leaned over, shaking his captain’s shoulder. The urgency in his voice was obvious as the packed walls of the earthen bunker telegraphed the distant barking of artillery blasts. Captain Johnston, only an hour into sleep and still in uniform, sat up on his canvas cot and adjusted his eyes. A faint hint of dawn leaked in through the curtain hung over the entrance invading the frosty dark of the dugout just enough to reveal a “somewhat concerned” expression on his number two’s face.

“Lieutenant Desmond here,” Wood continued, gesturing to a soldier stepping in, “says that this is heavier than usual.” It was Lt. Thomas Desmond, or “Desperate” Desmond as his own men called him, though to these officers he was a face from another unit, the 18th Infantry, which Johnston’s company had relieved in the front lines just hours before. Desmond and his men had held the trenches for the past three nights while Company E had been rehearsing for the next day’s battle. Assigned to stay behind as a “liaison officer” to help acquaint the newly arrived platoons with newly dug trenches, fields of fire, and enemy activity, Desmond agreed that Wood’s worry was well placed but added, “[I]t’s hard to tell; the old place has been picking up lately, and they’ve doused us two or three times a night.”

Captain Johnston was uneasy being this far from his men. His small command bunker had been hastily constructed by the French Moroccan unit that first defended this sector the month before. Dug into the face of the slope that descended away from the front, it placed Johnston three hundred yards behind the trenches. On arrival two hours earlier, he thought it “too far from the platoons.” Now the distance forced a dilemma: remain to gather delayed information about the bombardment and keep command intact, or walk up to the front and expose himself to the shelling. Johnston brooded as he and the two lieutenants “stood still in the hush appropriate to such moments,” he would later record, as “they listened to the clatter from without.” Only three months into his command of the 250 soldiers of Company E, he was becoming quickly acquainted with such lonely decisions.

At just twenty-one years old, Edward Scott Johnston was the youngest company commander in the division. One of seven siblings from Bloomington, Indiana, he had enlisted in the Army National Guard two years before, while a student at Indiana University. His unit was activated for service on the Mexican border, and he volunteered for officer training, securing his commission in the Regular Army the same year. When America entered the World War the following spring, young Lieutenant Johnston’s service, although brief, earned him promotion and he shipped off to France with the 1st Division.

Johnston had walked the gangplanks onto French soil with the first American soldiers in the first convoy to arrive the previous June. Since then, he had endured with his men each arduous slice that made up the hell of the Western Front. He had attended the solemn funeral of the first three young Americans killed in action the previous fall. He had survived nerve-shattering bombardments in two previous sectors and buried the grisly remains of young soldiers blown to pieces. He had endured the “hard winter” when “[s]ocks had to do duty as gloves” and “[s]hoes had to be held together with rags and string.” He had led intelligence patrols out into no-man’s-land, low-crawling on his belly, armed only with a pistol and hand grenades, where the faintest sound could trigger a German flare, then machine-gun fire, then death as certain as in a shooting gallery. He had seen gas shells fall from the sky and hiss out mustard clouds, causing men caught without masks to puke pools of blood as they gasped helplessly for air, and their skin boiled up into melting blisters. And just three weeks prior, he had witnessed his own battalion commander—his beloved major whom he called “a warm and living symbol of what we all were at our best”—crushed to death when a German high-explosive shell hit his headquarters.

It was that “soul-searching experience”—the death of his military mentor—that had affected Johnston most. He would later admit wondering to himself, “If this man can be slain, who can escape?” But like all other trying episodes in his service, it served only to buttress his indefatigable drive, and in what he gained from each experience he outpaced not only his men but his lieutenants, all of whom were his senior in age. It seemed that nature had parceled out to the young captain an unfair excess of those qualities that make good leaders.

Lieutenant Wood wrote of Johnston to the sister of a fallen soldier after the war: “[W]e were particularly blessed with a captain, who exacted our profoundest admiration both as an officer and a gentleman; as an officer I have not yet met his equal.” In the same letter, Wood likened Company E to “a happy family, bound together by the ties of good fellowship in a great common cause.” After eleven long months in France, Johnston himself felt his band of soldiers could finally feel “the confidence born of unity—the sense of being one no matter what betide.” His company, he would proudly state, “was certainly the best in the regiment,” and it was his four platoon leaders—lieutenants “all of unusual ability and character”—whom he would credit.

The welfare of these men—Johnston’s officers, his soldiers, his “family”—consumed his thoughts as he listened to the shellfire from his dimly lit dugout in such a lonely moment of command. Without a spoken word, Johnston pushed the curtain aside and walked out past his posted guard and over to First Sgt. Conley Hawk’s dugout. “Daylight had come,” he noticed as he stepped out into the open, “but a gray and sullen sky indicated that the sun might be late in appearing.” Johnston grabbed his first sergeant and two runners and together they rushed up the slope toward the approach trench.

Through the gray morning half-light toward the front lines they could see “[t]he bombardment on the plateau was intermittent, though fairly severe.” Out of the fog walked a French lieutenant who had been staking out a path for his tanks for the next day’s attack. Simultaneously, the French tank commander, the “plump and placid” Capt. Emile Noscereau, ran up and asked, in English, “The Boches are going to attack in a moment?” In a thick French accent, the lieutenant assured Noscereau and the rest, “Oh, no. I have just come from the front trench. It is merely a bombardment, for the most part by our own artillery.”

Somewhat reassured, Captain Johnston left the two runners in a portion of the approach trench with instructions to give immediate warning in case of any attack. As he returned back down the slope with First Sergeant Hawk and they split off to head to their respective dugouts, Johnston instructed his topkick to “keep in frequent touch by runner with the observation post.” Reentering his command bunker, Johnston passed Lieutenants Wood and Desmond, and in a tone he later admitted carried “a touch of severity,” he declared: “I intend to get a bit of sleep. Let me be called if something important develops, and only then.”

* * *

Back up in the front lines, the bloodletting continued. A mortar shell hit and “instantly” killed two more privates, Mike Dummitt of Detroit, Michigan, and James Adams of Kaysville, Georgia. The wounded writhed in pain on the dirt floor among a jumble of shovels and packs and dropped rifles. With no room in most of the cramped trenches for stretchers, many were dragged or carried, bleeding and with broken bones, out communication trenches for a long, painful journey to the first-aid station then driven by truck to a field hospital. Company casualty reports soon painted a picture of the peril at the front: “shell wound penetrating left leg,” “compound fracture left arm,” or “perforating wound of scalp.”

For the survivors, some injured and others paralyzed with fear, added to the thunder above and the screams around them was the familiar rattle of German machine-gun fire from across the plateau. Bullets sliced through the dirt parapet above, shooting sprays of soil into the trench and thumping against the rear trench wall in chalky bursts. The intrepid Lieutenant Avery, still moving up and down the line checking on his men, heard yelling from across the plateau, barely audible over the deafening siege of noise. Between gusts of enemy machine-gun fire he stole a glance over the top of the trench and noticed in the German lines “movement there … unquestionably something: a bobbing of helmets, a shifting along the line of the parapet.” Simultaneously, the enemy shelling stopped.

Avery recognized the stirring in the German line and the sudden lift of the barrage as a clear signal: this was not another routine morning bombardment. It was an attack. Or a raid, at least, and he needed to notify the artillery. He scrambled back through the trench, found his Very pistol, checked it had a cartridge, aimed it high, and fired. The magnesium flare fizzed up and split into three stars that glowed white against the gray, overcast sky, signaling the artillery two miles behind the trenches to lay down a barrage beyond Avery’s position. He waited. Hearing no response behind him, he impatiently loaded another flare cartridge and fired again, then again and again until finally he heard the unmistakable drumfire of the division artillery.

“There was a tumultuous thudding from the rear,” Captain Johnston would later report, followed by “a rushing across the sky,” a comforting sound for Lieutenant Avery and his men. But relief turned to alarm as the rushing sound changed pitch, then went eerily silent. Avery’s men braced, and the shells hit. Detonations again filled the trench, this time in concentrated groupings fired by their own guns. The division artillery evidently had the wrong coordinates for 3rd Platoon’s position. Avery grabbed one of his men from the trench floor and yelled, “Go to the captain. Tell him the Boches are attacking, and our barrage is falling on our own trench!” The runner shuffled out the communication trench as Avery rummaged through his box of flare cartridges, clutched a handful of single-star whites, and shot them up one after another to signal the artillery to “lengthen the range.”

“The trench had become a scene of horror,” Captain Johnston would later report. “[I]n places it was no longer a trench, but merely a smear on the ground.” Trapped in the prolonged pounding of his own artillery, Lieutenant Avery moved up and down what was left of his trench, lining his remaining men up at the parapet with their rifles ready to defend against the German infantry attack he knew was imminent. One of them, Pvt. William Cameron of Superior, Wisconsin, was standing with his rifle when a shell “exploded at his feet,” killing him “instantly,” a comrade would report.

Avery continued moving down the line pulling five-round clips from the ammo belts of his fallen soldiers and redistributing them by the handful to the surviving remnants of his platoon, actions for which he would be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. In the words of the citation, Avery “exhibited unusual courage in holding together his handful of men, after one-third had become casualties, and distributing ammunition to remaining men.” Suddenly he was enveloped in a massive explosion. Thrust down and crushed, things went dark as masses of earth collapsed, pushing him down with mounting force. Folded awkwardly, his head was smashed against his legs, which were still stuck out in a standing position. Dirt clumps and debris sifted past his ears, and from above he could hear only the faint, muffled sounds of men’s yells. To the remains of his platoon, Avery had disappeared from sight, buried alive.

Manning the trenches to the left of Avery’s position were the men of Lieutenant Curry’s 1st Platoon. Untouched by the bombardments, the soldiers here were lined up at the parapet with bayonets fixed and rifles ready. Their leader, John V. Curry, twenty-two and a native of Plains, Pennsylvania, was Avery’s best friend. The two had completed officer training together, shipped off to France together, and two months earlier arrived for duty with Company E together. In the morning the platoons they led would be assigned to advance side by side in the first wave of the attack. For the past ninety minutes, Curry had seen the prolonged high-explosive barrage that had been ripping up Avery’s stretch of trenches. Though Curry had no idea his friend was buried alive, he readied his own platoon, still at full strength, to defend his own line and Avery’s against any German infantry attack.

The barrage lifted from the front lines, and Curry could hear a series of loud, rhythmic detonations behind his position. Enemy guns had laid down a box barrage, patterned to trap the Americans up in the targeted trench and prevent reinforcements. For the Germans, ever methodical in their tactics, this was their cue to attack.

All American eyes in the front lines were fixed on the German trenches, and each soldier strained and repositioned himself to get a clear line of sight. The ground of no-man’s-land, covered with a blanket of knee-deep wheat, ascended gradually toward the German lines which, tailored by war’s calibrations, bent closer to the American trenches there than at any other point in the two-mile-long division sector. Above the wheat and through the fog and acrid smoke blanketing no-man’s-land, field-gray figures crowned with coal-scuttle helmets emerged from the earth. The watching line of doughboys leaned glued to the dirt of the trench front like guard dogs forcing restraint until the signal to attack. Flinching and ducking instinctively as enemy machine guns strafed the parapet with covering fire, they pressed their cheeks against the wooden stocks of their rifles, each soldier lining up over the sight post of his barrel a walking gray figure to drop, awaiting the order to fire.

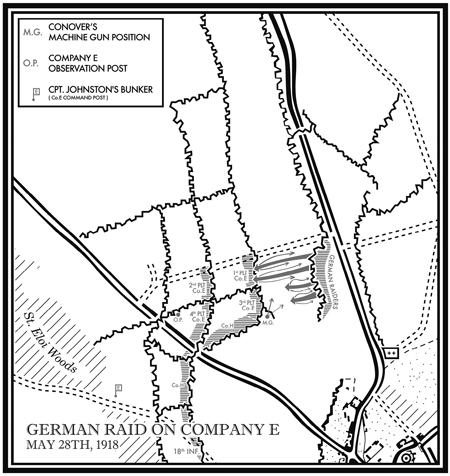

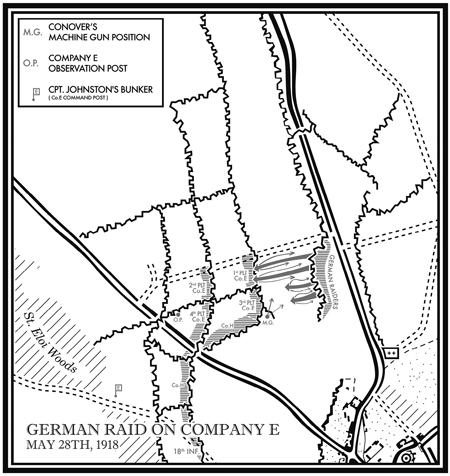

In the trench beside 3rd Platoon a machine-gun crew waited, concealed behind a clump of trees. The gun-crew chief, twenty-year-old Cpl. Richard “Dickie” Conover of Newport, Rhode Island, stood peeking over the parapet, waiting for the approaching Germans to get closer to give the order to fire. The loader held a stiff twenty-four-round ammo strip out from the receiver with an open box of more stacked at the ready. The gunner leaned in on the shoulder rest and eyed the approaching enemy down the long steel barrel of the Hotchkiss, tightly gripping its wooden handle, his trigger finger ready to squeeze out grim retribution.

Most of these doughboys had spent weeks and months in trenches learning to hate the Germans—the “Huns,” the “Boches,” “Fritz,” “Jerry”—an unseen, faceless adversary that lingered beyond the barbed wire and darkness of no-man’s-land, stripped of human qualities. Now as they eyed the kaiser’s soldiers approaching steadily, loaded with grenades and clutching Mauser rifles with fixed bayonets, individual human features began to emerge. Encountering for the first time the face of the enemy in a clash of kill-or-be-killed, these young Americans saw war instantly reduced to its tragic potential. One private muttered nervously, “By God, I’ll bet they are as scared as I am.” A sergeant defiantly whispered, “Let ’em come. None of them will go back.”

* * *

The “bit of sleep” Captain Johnston had intended to get never came. “A dull but rhythmic thudding, that had woven itself into the very stuff of dreams,” as he would later describe it, continued from the front, keeping him and Wood and Desmond wide-awake in the gradual growing light of the bunker. Johnston’s concerns over the ambulatory nature of his command mounted, and he lamented aloud to himself what “bad business” it was to be “this far away from the outfit.”

Before the words had left Johnston’s lips, a soldier dove through the curtained entrance and landed on the dirt floor. It was Lieutenant Avery’s runner, who had sprinted and dodged his way through the shellfire down the communications trench from the front lines. “Gray with dirt, and somewhat rumpled as to appearance,” the young private stood up, saluted his captain, caught his breath, and delivered Avery’s message: “Sir, the lieutenant directs me to say that our own artillery is firing on the 3d Platoon trench.”

But the winded runner neglected the first part of Avery’s message—that the Germans were “attacking.” And neither he nor any of the officers present could know that Avery was slowly suffocating under a crushing heap of upturned earth. Acting on the only information he had, Captain Johnston instructed the runner to return and inform Avery that for the moment 3rd Platoon “simply had to grin and bear it” and that Johnston would be on his way up shortly. He then scribbled a message reporting the friendly fire, gave it to another company runner, and with a slap on the back sent him sprinting to the battalion commander’s bunker.

As Johnston buckled on his gear and announced to Lieutenant Wood, “I’m going up to look at things,” the curtain swung aside again and into the small, crowded bunker popped the battalion intelligence officer, Lt. Benjamin Gardner. As a former Company E platoon leader, his was a familiar face. “[T]he courteous calm of our distant southwest was his usual demeanor,” Johnston noted of the lanky Texas native, but in this moment his animation was unmistakable; “rarely had he been seen in a state of so great excitement.” Apparently the surgeon at the first-aid station was reporting high numbers of wounded coming in, and the battalion commander had sent Gardner to get a report.

Just as Captain Johnston was assuring Lieutenant Gardner it was only a bombardment, concrete news from the front finally arrived. It was a runner from Lieutenant Curry’s platoon, who caught his breath, saluted, and relayed, “Lieutenant says Boches are attacking.”

Johnston wasted no time. “Notify battalion.” His brisk command hung in the air of the bunker as he and Gardner swished out the canvas curtain and headed toward the front.

* * *

From behind their patch of trees in the front-line trench, Cpl. Dickie Conover and his machine-gun crew could see the Germans approaching in two waves, each of about two dozen men. Young Conover was the ideal embodiment of America’s presence in the Allied lines, perfectly situated to play his part dismantling the German myth that the doughboys could not fight. Back home, he had been a star athlete in prep school, a member of the rowing team, football team, and captain of the hockey team. Within two weeks of America entering the war, Conover was on a ship crossing the Atlantic to serve with the American Field Service, where he trucked ammunition to the French front. Once the US Army finally caught up with him in France, he enlisted and joined the machine-gun company of the 18th Infantry. Now over the din of the artillery barrage, he yelled to his gunner to wait just a little longer to fire—wait until the enemy got a little closer.

As the line of Germans reached the thin, single strand of barbed wire about fifty yards from the American trenches, Lieutenant Curry yelled “Fire!” The loud “steady, even popping” of over seventy rifles firing was swallowed by the hanging fog, and the charging gray figures dropped mid-stride beneath the wheat surface, some for cover and others injured and dead. As the American rifle fire continued, rustles in the grain evidenced German movements as coal-scuttle helmets appeared in flashes of forward sprints and gray-sleeved arms swung above the wheat tops slinging stick grenades toward the American trench line.

In a crackling frenzy, Curry’s doughboys continued firing into the fog and wheat, popping their five-round clips at muzzle-flashes, movement, or any signs of a live enemy. Down on the trench floor, handfuls of men huddled to duck grenade blasts, while others lay shaking, seized by the shock of combat. Above, rifle volleys continued to send bullets slicing in both directions as more Germans fell and still more grenades came flying end-over-end into the trench. Buried down below and still struggling to breathe, Lieutenant Avery could hear only “the thin crackle of rifles” from above as the broken remains of his platoon stood their ground.

As the second wave of Germans reached the wire, Corporal Conover’s machine gun opened up, the flashing white flame on the end of its barrel slueing left and right as it shot out a zipping torrent of bullets from behind the trees with a sustained, deadly rattle. Nearly every standing figure in no-man’s-land was mowed down, cut to ribbons. As Captain Johnston would later report, “the rear line of attack went down into the wheat as if swept by a scythe.”

Over on the far left, in front of 1st Platoon’s trench, the Germans had lunged past the wire and were only yards away, tossing grenades and firing Mausers from kneeling positions in the wheat. The attackers pushed closer and rifle fire was exchanged at almost point-blank range. Without warning, one of Lieutenant Curry’s men, twenty-three-year-old Pvt. John Drbal, threw down his rifle, climbed over the parapet, and ran toward the Germans with his hands up, motioning surrender. Five Germans gathered around him and he yelled something to them. “Whatever it was, it meant a lot to them,” Curry later reported with lasting astonishment; “I guess it was about the attack tomorrow. They were certainly excited.”

The soldiers of 1st Platoon absorbed the scene in stunned bewilderment. As one of the Germans blew a whistle and signaled to return back to their own lines, Curry’s men unloaded their rifles on the group. “All six of them went down,” Curry noted. “We were careful not to let them crawl away. Couldn’t let that bunch go—any of them.” Captain Johnston would report that “the group of six figures … gray and olive drab alike, they fell in a huddle amidst the wheat, and lay still.”

John Drbal Jr. had been recently drafted out of Wisconsin, the older of two sons to Bohemian immigrants. When his shot-up body was recovered from no-man’s-land, Curry would identify him as a “new replacement” and place on him the blame for “other trouble” from the past month, “distorted messages” and “false orders.” Captain Johnston would later wonder at great length about this “deserter, traitor, spy” from his company, and the battalion commander would estimate him to be either “a desperate cold calculator, or a misguided young fool.” Any truth that survived Private Drbal is now lost to time, and he lies under a Latin cross in the Somme American Cemetery, resting forever in the ranks of those who wore the same uniform.

* * *

Over on the far right, still directing his machine-gun crew, Corporal Conover sighted commotion to his left toward the 3rd Platoon trench. In the midst of the mayhem, obscured by fog and lingering smoke, a small clutch of German attackers appeared to be forcing their way into the front line still being desperately defended by the decimated remains of Avery’s men. Before Conover could react, he saw the gray forms reemerge holding two doughboys at gunpoint, rushing them back across no-man’s-land.

With a dogged determination to rescue his comrades that left him blind to the enemy machine-gun bullets still sweeping the parapet and plateau before him, Conover grabbed his rifle, climbed out of the trench, and yelled for his crew to cease fire and follow. He ran forward a few feet beyond the parapet to get a good angle, lay down in the open ground, and fired. His crew climbed forward with their rifles and joined him. “[W]e all started to pick off the Germans who were taking the Americans back,” one of them later recounted. They were successful in finding their marks, and both American soldiers captured by the Germans made it back to the line unharmed.

But their muzzle flashes betrayed their position, and enemy machine guns ranged in. Unfazed, Conover was still “cool, enthusiastic and was doing good work,” according to the soldier lying next to him. Like the first few heavy drops of an arriving rainstorm, enemy bullets pelted the dry dirt all around, and in a few moments the crew noticed Conover was gone. Finding him lying shot in the bottom of the trench, the crew climbed back in and asked their corporal if he was hurt. He noticed one of them was empty-handed and said, “I’m through, take my rifle.”

Those were his last words. His lieutenant would later say he “had a smile on his face and he died with the knowledge that he had done his utmost in performance of his duty.” Conover was buried in the trench where he fell. The following Christmas, his father, serving in Europe as a chaplain, would visit the very place his son died. In the mud he improbably found the last letter he had sent Dickie. It closed with the words “in spite of all the turmoil and death in which you are living, you can be at perfect peace in the arms of your Heavenly Father.” Two years after the war’s end, Cpl. Richard Stevens Conover was finally removed from the dirt of the trench and reburied in the Somme American Cemetery, where he rests today.

* * *

Johnston and Gardner arrived at the front after scrambling “over blocks of earth and debris” and sliding “down into new and deep depressions” through the approach trench heavily damaged by the box barrage. On the way up, they encountered men crawling out from under demolished sleep dugouts and shell-shocked soldiers who seemed “temporarily dazed and deafened” and “unable to answer questions.” To the left, Johnston saw Lieutenant Curry and his men still firing their rifles over the top. Out in the wheat of no-man’s-land, there was a “flurry of movement,” which Johnston estimated was “the last desperate rush” of the German attackers. “A few figures were all that could now be seen to the front, moving about through the wheat at some distance; now and then one of them fell.” The few German survivors were backpedaling through the killing field to their own trench. Johnston ordered a cease-fire, and the fight was over.

The lifting fog and rising sun revealed a no-man’s-land scattered with the gray uniforms of the German attackers, some injured and many dead. Surveying the damage, Johnston estimated that “only three or four” of the Germans “returned alive to their own trench.” In the bottom of the trench near him, a German lay wounded with a bloody leg. He had made it all the way to the American line when he and one of Curry’s soldiers clashed with bayonets. Each had fired at the other, a bullet hitting the German’s thigh and his own merely splintering the American’s wooden rifle stock. Another German, unharmed, simply walked out of the wheat up to the trench and surrendered. Both were immediately taken to the rear as prisoners.

As Johnston made his way over to 3rd Platoon’s position to look for Lieutenant Avery, he found “not a trench, but a twisted conglomeration of weapons, dirt, dead, and wounded.” He began coordinating cleanup and reorganization as medics dressed wounds and stretcher bearers removed the wounded. Soldiers dug for Avery, a task made more difficult by a collapsed trench that shrunk the space to work in and compounded the places to dig. Lieutenant Curry came over to assist, calling his friend’s name out and listening for a response.

Buried deep, Avery could only hear voices directly over him, and more than three hours would pass before he heard the faint sound of Curry’s voice from above. “[H]e was immediately over me he called my name and I answered,” Avery later remembered. As muffled sounds of recognition, digging, and Curry’s “calls of encouragement” came from above, he knew he would make it. He was pulled out “almost suffocated, and in pitiful physical condition,” Johnston observed. Avery had been buried for three and a half hours, and rescue had come just in time. “Ten minutes more and I know I should have suffocated.”

In a “tender way,” Avery noted, Curry helped lift him onto a stretcher. Though paralyzed on one side, exhausted, and nearly suffocated, Avery still had, in Johnston’s view, “a proud mental state,” asking for news and updates about the raid. As he was carried off, lying on the stretcher smoking a cigarette, his buddy Curry wished him well. Avery later recalled of the moment, “I think we both cried a little.”

But the morning would still claim one more life. Either in response to an errant flare or a distorted message—details are conflicting—the division artillery fired again on the front lines. A few detonations, then silence. Two more soldiers were badly injured and one, the liaison officer, Lieutenant “Desperate” Desmond, lay dead. One of the high-explosive shells had slammed the twenty-two-year-old Randolph, Massachusetts, native so hard against the trench wall that it cracked his skull and shattered his pelvis and most of his ribs. He likely died instantly. A private sprinted out of the communication trench and down the slope, and delivered the news to Captain Johnston, who was headed back to his bunker to file a report. Johnston would later remember that the runner “sat down suddenly, this steady, brave, young soldier, and tears rolled down his face.”

Of the raid, German reports would list forty-two of their fifty attackers as casualties. Their commander had sent them forward with urging “that prisoners must be taken at all costs,” but the few survivors who managed to make it back to the safety of their own trenches did so without prisoners and without information. Their mission had failed in every respect. For the Americans, as the rush of adrenaline faded, they knew only what their five senses told them: that the scent of cordite and shrieks of otherwise fearless grown men had left some with the palpable taste of fear and others with a thirst for revenge. They could not yet know the final numbers or where precisely this enemy raid fit into the big picture, but they knew they had successfully defended their line and allowed no prisoners to be taken.

The cost was heavy. Company E suffered nine men killed and a dozen injured; Company H, in the trenches to the right, had twelve men killed—including a platoon leader—and twenty injured; and six members of the 18th Infantry were killed. In all, over fifty men had been plucked from the center of the first wave of the following day’s attack.

For most survivors, this fleeting episode was their first taste of war, and they bore its imprint. The expressed carnage, whether nerve-shredding proximity to deadly shell blasts or the sight of a friend’s final moment, left some shaking, their psyches fractured by combat exhaustion—what then was still universally termed “shell shock.” But for many it roused dormant courage from within, and it demolished any remaining myth of German invincibility ingrained in their minds. They were no longer the uninitiated, and when the whistles sounded the next morning, they would go over the top as veterans.

Captain Johnston returned to his bunker for rest that would not come easy. His company stood at the starting line, less than a day from Zero Hour, bloodied but proven. The courage of his men under fire urged thoughts of his late battalion commander and mentor, who “had told them everything they would have to do,” and “[w]hen the time came, they simply did it.” Like a proud father, Johnston wrote that his lieutenants led “with courage and with dogged endurance,” and the “[i]ndividuals and platoons cooperated to good effect” with “admirable unity of purpose.” Doubtless it would be “a source of gratification to higher authority.”

* * *

The next morning at dawn, Captain Johnston’s men would go “over the top” and into the breach, forming the center company of the first wave of the first American battle of the war. Their crossing of no-man’s-land would be their final steps in a long journey to war. It was a journey that had begun thirteen months earlier, when the United States declared war on Germany, abruptly transporting the reality of carnage and bloodshed of the Western Front across the Atlantic and into American homes. Before then, most of these young men had been living lives peacefully undistracted by the worlds falling apart in Europe. With a sudden call of duty they had flocked to the colors, answering their president’s call to fight to make the world “safe for democracy.”

It was a time that suddenly seemed a lifetime ago, before the irretrievable deaths of the morning raid, and a world removed from the men resting up in the front lines, many of whom would breathe their last the next day.

It is there, America’s entry into the World War, that their journey—and our story—begins.