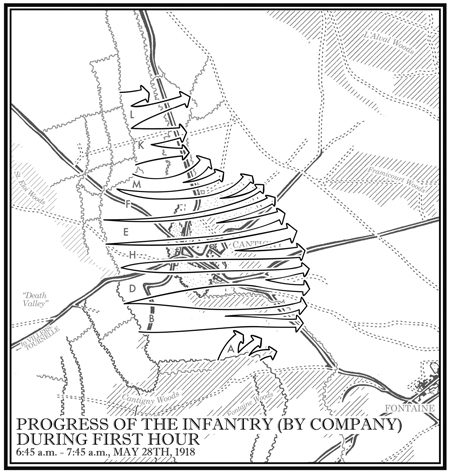

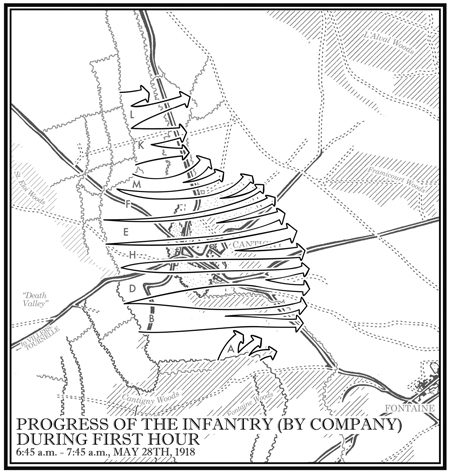

Though hundreds of German soldiers were still hiding or trapped beneath Cantigny’s ghostly ruins, the village was once again in Allied hands. For the 1st Division, the heft of numbers, speed, and metal had won the hour. Though stymied on the flanks, seven of the nine infantry companies forming the attack vanguard had reached their objectives, and among doughboys in the process of furrowing out fresh trenches and remapping their small stretch of the Allied lines, a new confidence took root. With Cantigny in their tenuous grip, overall victory in the battle felt within reach.

But the day’s drama was still unfolding, and this was only the first act. Biting off a chunk of enemy territory gave no assurance of success, no promise that it could be held. Armies up and down the Western Front had tried and tried again, and most had failed. For the Americans, the advantage of surprise was quickly evaporating, and with French artillery batteries exiting the battle, the weight of steel was about to tilt decidedly in the Germans’ favor.

* * *

“The pick or the shovel, when the objective is reached, is mightier than the gun,” one officer would later remark. More than three dozen platoon leaders along a fragile new mile-and-a-half-long front plotted imaginary lines on the ground where their men were to establish trenches in the shell-cratered dirt. Troops shed packs and ammo bandoliers, grabbed picks and shovels, and commenced the big dig. As with the initial attack, the two flanks saw the heaviest fighting. For the doughboys Company K, the immediate danger was their open left flank.

“Just as the digging began, a machine-gun barrage was put down,” Lt. Si Parker, establishing his outpost up near the haystack, would report. Maxim fire came in torrents from Germans on the left flank and the distant l’Alval Woods. Pvt. Emory Smith, chasing a German he had spotted out in front of him “dodging from one shell hole to another,” leveled his Springfield and fired just as the wall of machine-gun fire knocked him back. “Just as I fired at the Dutchman [sic], being in an erect position, I was shot in the breast and for a moment everything was black,” he would recall. Smith fell into a shell crater and lay dazed while the company dug in behind him. Though Smith was far forward in a position raked by automatic fire, Captain Mosher made his way up to the crater, kneeled to check on him, gave him an aspirin, and told him to hang on until dark, when he would send a stretcher forward to evacuate him.

All along the line, upright, digging doughboys proved easy targets. Pvt. Amedeo Gialanella was “taking an entrenching tool from comrade’s pack when shot thru [his] head with a machine-gun bullet, killing him instantly.” Digging an outpost with his squad, twenty-year-old PFC Charles Harsch, “a quiet fellow” from Brockport, New York, was shot in the forehead. When hit, “he fell backwards and said, ‘My God Mother,’” then died, a watching corporal would later relay.

Twenty-year-old Pvt. Eugene Griepentrog of Milwaukee “made a step for a shell hole to start digging in when a machine-gun bullet penetrated his heart, killing him instantly,” Pvt. Harry Langley of Indiana noted. “When he was shot, he fell on his face.” Also from Milwaukee, seventeen-year-old Pvt. August Beckman Jr., the youngest of five children to German immigrants, was shot through the right leg and fell, but was able to low-crawl to Private Langley’s shell hole. As Langley opened his first-aid pack to bandage the wound, Beckman told him to write his mother if he should die. Before Langley could help him further, Beckman was shot through the heart. Nearby, Cpl. Harry McCredie of New York stood momentarily to dig a connection between two shell craters and was cut down with two bullets through his groin. “As soon as he was injured he became unconscious,” Langley would recall, “remaining so until he died” about twenty minutes later.

Machine-gun fire from a half dozen German guns swept side to side and back again, perforating anything exposed above the lips of shell craters and making it impossible for the hunkered survivors to dig any kind of cover. Cpl. Jethers Schoemaker of Georgia poked his head up, “was struck in the left temple with a machine-gun bullet, and died instantly,” a comrade would report. PFC Robert Veal, also from Georgia, was shot through the throat and collapsed. Unable to make any statements, he fought the end for an hour before bleeding to death. And eighteen-year-old Pvt. Matthew Rivers, defiantly digging despite the danger, was shot in the chest. He dropped his shovel, said calmly to a fellow private, “I’m shot,” then dropped over dead.

The teenage soldier known in his platoon as Matthew Rivers was actually Matthew Juan, a Native American from the Sacaton Indian Community in Arizona. Having shown athletic promise in baseball, rodeos, and calf roping from a young age, Juan was working for the Ringling Brothers Circus to help support his widowed mother when America entered the war, and being too young to register for Army service without parental permission, he registered under the false name “Matthew Rivers.” When he shipped out for France in February, his transport, the SS Tuscania, was torpedoed and sunk by a U-boat. More than two hundred died, but “Private Rivers” was rescued, making it to France for assignment to the 28th Infantry just before the move to Cantigny. After the war, correspondence between his mother and the War Department would confirm his identity, and his body was shipped home at her request. Today, in a Sacaton park named in his honor, Private Juan is memorialized with a life-size statue and a stone obelisk, on which a plaque reads: “Dedicated to the Memory of Matthew B. Juan, Co K 28th Infantry, First Arizonian Killed in the World War, Battle of Cantigny, May 28th 1918.”

* * *

A mile south, Lt. Robert Anderson’s Company A soldiers worked to dig the anchor for the right wing in the eastern edge of the Cantigny Woods under increasingly irksome machine-gun fire from Germans hidden in the Fontaine Woods. Twenty-nine-year-old Cpl. Robert Finnegan of Pennsylvania led a team out in the open to string barbed wire before their position and was shot in the shoulder blade and rib. But he concealed his wounds, and still under heavy fire, led his team scurrying back to the wood line and into their shallow foxholes. Finnegan fired his Chauchat on the enemy-infested woods across from him for more than an hour, providing covering fire for his digging squad before falling weak from blood loss. He was evacuated on a stretcher to a field hospital, where he would succumb to his wounds midafternoon. For his actions, which “encouraged his men by his example of fortitude,” Corporal Finnegan was posthumously awarded both the Distinguished Service Cross and the Silver Star. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

The two platoons that had swung out and joined the assault through the open ground had since become trapped by the heavy Maxim fire in the low ground of the ravine where they dug for cover, unable to connect with Company B’s position up on the ridge. “We dug while the sun was coming up,” Pvt. John Johnston would describe, “and half of the boys dug, and dug frantically with their helmets.” Any standing figure was perforated by the torrent of bullets, so men lay flat on their stomachs scratching out holes with ration tins and helmets, piling dirt and uprooted weeds before them for a few precious inches of defilade. “Some of the men had tough luck, for they ran into rock,” Private Johnson would add.

Up on the ridge, after clearing the German trenches lining the dirt road, Captain Oliver moved Company B forward to connect with Company D on the left, a movement covered by the two Hotchkiss teams and men operating the captured Maxim. In the rehearsal, the company commanders had been instructed to establish two trenches for defense-in-depth: a line of surveillance with machine-gun or automatic-rifle outposts out front and a line of resistance fifty yards back. Oliver ordered two platoons to dig the rear trench, two to dig the front trench, and set up three Chauchat outposts—two beyond the front line and one at the road on his right flank to cover the gap between his unit and Company A.

But on schedule, the standing barrage in the wheat field before them stopped, lifting a valuable smokescreen and clearing sight lines for enemy Maxim crews in the Fontaine Woods three hundred yards away. “As soon as we reached the objective we ran into machine-gun fire, and digging a trench under these conditions is not the pleasantest occupation I know,” Lieutenant Poe would soon write home. “Most of our losses occurred at this spot and our company was badly cut up as any. I thought the sight of seeing men killed would affect me more. The first to fall was about 10 feet away and I knew he was killed the moment he fell.”

While Chauchat and Hotchkiss teams did their best to put down covering fire on the distant wood line, panting doughboys in sweaty tunics dug for their lives. Sweeps of a half-dozen Maxims merged into a nerve-wracking din, and digging soldiers were bowled over dead, life after life extinguished and added to the day’s grim tally. Twenty-five-year-old Pvt. Samuel Tunno, an Italian immigrant from Akron, Ohio; eighteen-year-old PFC Abner Cooper, the fourth of eight children from Monticello, Mississippi; Pvt. Roman Dzierzak, a Russian immigrant drafted in only his fifth year in America; Pvt. Harry Heimbach of Pennsylvania; Pvt. Charles Drake of Mississippi; PFC Simon Czech; Pvt. Dewey Beam; Pvt. Joe Kasper.

Men were forced to roll their dead friends out of the way to keep digging, left to wonder if the next sweep of bullets would be the end. Pvt. Harry Gums was still lying in a shell crater bandaging the leg of his Janesville buddy, Pvt. Otto Hanson, when machine-gun fire pelted his position. A bullet hit Gums near his elbow, tearing through the length of his forearm and ripping tendons before exiting his thumb. Having lost all feeling in his hand and use of his arm, he wrapped a bandage around it to stop the bleeding, grabbed his rifle with his good arm, and held his position for another hour before finally being evacuated.

Lt. James Lawrence, whose ear had been “chewed” up by a bullet on his charge out of the ravine, was directing his platoon’s digging in the wheat field when, as he would describe, “I tried to stop another bullet, but it was too lively for me; it sideswiped my upper left chest and around under my side and cut through my upper arm.” He was evacuated late morning and would recover after a stay in the hospital, calling himself “mighty lucky” but joking that his shot ear would forever be “about a size smaller.”

* * *

Digging new lines to Company B’s left were the men of Company D, led by thirty-five-year-old Lt. Soren Sorensen, a ten-year Army veteran who had been promoted for bravery in the Philippines. He would report that, much like Company B, “most casualties were on reaching objective where we received heavy machine-gun fire from wood on our right.” In fact, over their crossing of no-man’s-land and sweep through Cantigny, Private Dust—killed by an artillery short—had been the company’s only death. After rushing to the objective, twenty-six-year-old PFC Walter Dawe of St. Louis was shot in the back “between the shoulder blades” as he began to dig in. He died instantly, killed by a hidden German machine gun “passed up in the attack” before flamethrower crews could catch up and clear it, a sergeant later recalled.

“When they began digging in, the Boche machine-guns ranged in half a circle began spouting bullets,” Lt. George Butler noted. Fortunately, in the rear line of resistance that his platoon was consolidating, the creeping barrage had left a series of deep craters the men used as starting points. “[A]ll possible use was made of shell holes which were deepened and later connected up by the men in the holes digging toward each other,” Butler would report. But their position exposed them on a forward-sloping field at the mercy of enemy guns, a topographical handicap that the lines of Marshall’s flat map board had not revealed. The company, as Butler later bristled, “found itself on the highest nose of the plateau and was forced to dig in under a fury of machine-gun bullets which inflicted severe punishment on it.”

Pvt. William Fishette, an Italian immigrant, was struck before he could make any progress with his shovel. “The bullet hit him in the forehead, and killed him instantly,” his corporal reported. His friend and fellow Italian American, Pvt. Antonio Grassi, was shot through the stomach, folding over in pain until stretcher bearers finally evacuated him. He would undergo surgery to remove the bullets, hanging on in pain before losing the fight four mornings later.

Trying to cover the consolidation, Cpl. George Anslow of Boston, the company sharpshooter, was sniping Germans along the distant wood line while his fellow doughboys dug. He was peeking over the dirt lip of the parapet when, as his sergeant later recalled, he “[d]ropped his head a little.” A couple of men in the trench “asked him why he did not fire” and “if the Germans were coming over,” but he was silent. They tugged on him and he collapsed, having been “killed instantly” by a German bullet above his right eye.

Machine-gun fire chewed through Company D’s ranks, and it was not long before Lieutenant Butler was struck. “It was like a pack of bumblebees,” he said of the bullet that entered his upper thigh and exited the flesh of his hip. “It felt like being hit with a rock,” he noted. “The pain was not much worse.” The bullet had not hit any bone, but he was bleeding freely. Butler left his men under the charge of Sgt. Roy Hockenberry and limped the half-mile journey back to a first-aid station, where he was carried to a field hospital. After surgery he made a full recovery, save a slight limp he could never shake. But his platoon sergeant, Roy Hockenberry, a twenty-five-year-old from Pennsylvania, met his end only moments after Butler left. He had just started turning the soil up with his pick when he was shot. “He was hit by at least five bullets, which pierced his chest and stomach,” a corporal in the platoon reported. Hockenberry fell flat, grabbed at the bloodied uniform covering his chest, and with his final breaths, he muttered, “I wonder how deep it went in.”

* * *

Back in Cantigny, flamethrower crews and riflemen of the third wave moved methodically from one pile of rubble to the next, purging cellar after cellar of hiding Germans. Correspondent James Hopper noticed them immediately when he entered the village: “Now I could see into its ruined main street. There was a group of our boys standing there, about a French soldier who held a hose end down into a cellar entrance.” Flamethrower operators wore Adrian helmets and long, leather trench coats with bottoms buttoned back at the knees. Strapped to their backs were two metal tanks with hoses extending out arm’s length to a nozzle, and slung over their shoulders were sacks full of hand grenades.

Cpl. Daniel Edwards, a machine gunner attached to 2nd Battalion for the attack, watched one in particular, an older man with “a bushy black beard” who calmly puffed on a pipe as he worked. “Placid and methodical, he walked along,” Edwards recalled, “smoking his pipe and looking around for dugouts.” When the loaded-down Frenchman spotted a cellar, he would lumber to the entrance, yell “Raus mit ihm!” down into the darkness, then, as Edwards noted, “trained the nozzle down into the dugout and let her rip. Then he’d take out a grenade, tap it on his tin hat and toss it in.”*

Each time, the scorching sound of spraying flames attracted nearby soldiers who would gather around with rifles ready. After the muffled grenade detonation sounded, doughboys waited for survivors to appear. Masses of field gray scurried out with hands up and faces black with soot and smoke. At the tips of bayonets, they were herded into prisoner columns—the captain of the French flamethrower company reported 136 enemy soldiers taken prisoner in this manner. James Hopper rushed to get a close look at the captured enemy. “So many young boys—they looked hardly sixteen,” he would write. “So comically bedraggled and piteous, those warriors whom it has been the great care of their masters to make appear dreadful and terrible—they looked so small, their clothes were so wrinkled, their faces so dirty.”

Of the prisoners filing back from Cantigny to the American lines, one officer observed “some running but few looking back and all headed for safety, a craven looking lot but they did march well even under such circumstances.” One soldier noted, “They were so thin it looked impossible for them to be alive.” As American guards escorted the first gray columns back through gun positions of the 6th Field Artillery, Maj. Raymond Austin noticed most “seemed quite young and all were apparently glad to be captured excepting the officers.” He gave one German a box of cigarettes, “which seemed to surprise him,” and spotted a lieutenant who “couldn’t have been more than 17. He must have been a Von-somebody’s son. He kept his big helmet down over his forehead and his head bowed.”

But many Germans who had managed to survive the dawn bombardment could not endure the fire bath inflicted by flamethrowers. Cpt. Clarence Huebner watched one German soldier scurry out of a flaming cellar “just as I had seen rabbits in Kansas come out of burning strawstacks [he] ran ten to fifteen yards then fell over singed to death.”

Destined to lead the 1st Division in the D-Day landings twenty-six years later, twenty-nine-year-old Clarence R. Huebner commanded Company G, designated the “reserve” company for 2nd Battalion. Two of his platoons were to build a strongpoint out in the orchard while the other two swept forward and back again through the town’s rubble-clogged streets with flamethrower teams until all Germans were evicted.

Captain Huebner first learned to shoot as a young boy growing up in Bushton, Kansas, picking off rabbits and squirrels with .22 short ammunition he had acquired by trading in Buffalo bones because, as he would later recall, “We didn’t have money in those days.” He was educated in a one-room schoolhouse, attended business school in Nebraska, then worked as a stenographer and typist for the Chicago Burlington & Quincy Railroad. But the true course of Huebner’s life was not set until he enlisted in the Army at twenty-one. As a soldier in the peacetime military he rapidly bloomed, passing the exam for an officer’s commission after six years in the enlisted ranks. Service as a platoon leader south of the border against Pancho Villa’s troops filled his absorbent mind and informed his subsequent thinking. America entered the war just as he was completing infantry school at Fort Leavenworth, and he crossed the Atlantic with the division’s first convoy as a company commander. Since then, Huebner had displayed an innate capacity to command, and that morning he stood as the battalion’s senior company commander—Lieutenant Colonel Maxey’s number two.

Maxey was still cleaning out the orchard on the north side of the village, where sporadic firefights continued. The tanks had shut down the German machine-gun nests behind the hedgerow, but the crackle of Mauser shots from a few elusive enemy soldiers continued. Cpl. Boleslaw Suchocki was still lying down on Maxey’s order, and through a break in the hedges, Suchocki spotted a figure standing behind a single apple tree about forty yards distant. “I took good aim right through the bushes, fired and saw that something fell to the ground,” he would recount.

Tanks plowed through the hedge and Maxey ordered everyone up again and to the other side, where they ran into an enemy fire trench full of dugouts and scrambling figures in field gray. An automatic-rifleman next to Suchocki began pouring fire into the trench and was quickly shot down. Most men dropped but Suchocki and a comrade ran toward the trench, and as he would later describe: “I saw that [as] a Dutchman [sic] stick his head out over the parapet I shot at him and he rolled into the trench.” Overwhelmed, two dozen Germans stood, dropped their weapons, and raised their hands in surrender. Angry doughboys swarmed, shooting and bayoneting them until Maxey ran over and put a stop to the killing. As Suchocki would recall, “[H]e raised his hand and said, ‘boys, spare them, take prisoners.’” For “alone killing four enemy snipers under heavy machine-gun and rifle fire,” Corporal Suchocki was later awarded the Silver Star.

* * *

While machine-gun fire was shredding exposed riflemen as they tried to dig new lines, the big guns of the French artillery were so far keeping German artillery silent. “During this time the counter-battery work of the 10th Corps Artillery,” a division artillery officer would note, “was excellent.” In just the first hour of the attack, a French battery of 240s had sent a hundred five-hundred-pound shells sailing into enemy gun emplacements, and a single battery of trench mortars had lobbed nearly eight hundred shells into reserve positions to thwart counterattacks.

But as each French gun crew fired their last allotted shells, they pulled down camo netting, yanked up wheel blocks, hitched guns to horses and tractors, and trooped out for a day’s journey south to jump into the larger fight brewing near Champagne. “Orders for the withdrawal of more French artillery arrived before the advance had been completed,” fretted George Marshall of news that soured the mood in Colonel Ely’s command post. The keystone of the second phase of Marshall’s plan—holding the position—was counter-battery fire. Every new draft of the attack plan had elevated more and more the role of the supporting French artillery, finally charging it with “neutralization of enemy batteries … with all the intensity possible,” a job for which the largest remaining guns—the 155s of Sitting Bull’s artillery—lacked the reach.

Since Zero Hour, not a single German shell had yet caused an American casualty, but reports quickly poured into Ely’s bunker of soldiers up in shallow, exposed, half-dug trenches coming under increasingly crushing shellfire. “The German guns, unsuppressed by our lack of counter-battery fire,” Marshall noted, “opened a violent bombardment on the newly captured positions,” and, he added, “troubles were coming thick and fast.”

* * *

Up in his observation post, Lt. Daniel Sargent noticed that “everything changed. Our artillery fire had pretty much ceased, but a German artillery fire took its place.” In the village ruins and all along new lines being dug by American riflemen, enemy shells “raised a cloud of yellow smoke, similar to that which we had seen raised by the bombardment a few minutes ago.”

On the right flank, Lieutenant Sorensen’s digging men of Company D, already under punishing machine-gun fire, faced a storm of fire and lead and steel from above. Pvt. Isadore Czarniewski was digging to deepen a shell-crater when a 77mm shell “made a direct hit and mangle[d] up his body,” his corporal would report. Fragments tore into the back and both legs of Pvt. James Papineau of Saginaw, Michigan, who was pulled from the scorched dirt and carried to the field hospital, where his wounds would prove mortal three days later.

Another fragment tore into tall, lanky Paul Davis just as he “had started to dig in.” His sergeant would report that the twenty-two-year-old private was “instantly killed,” and shellfire that followed left no trace of Private Davis’s body. Back in Idaho, his mother Eliza’s grief over his loss would only deepen with news that his remains could not be found. She found little comfort in learning his name was inscribed in the chapel of the missing, and declined the government’s offer to send her on a gold-star mother’s trip to France. She preferred them to send her the equivalent funds “so I can buy a nice stone to put in our cemetery to his memory so he will never be forgotten.”

Nine years after the battle, a French hunter pulled two reflective metal disks from a field south of Cantigny. He recognized them as American military ID tags, and another two years later, he passed them to a Marine Corps officer who was visiting the battlefield. On each disk was stamped the following: PAUL DAVIS CO D 28 INF. The Marine mailed them to the US Army’s Adjutant General Office, and to this day they remain buried in a manila folder deep within the archives of the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri. Eliza Davis passed away in 1947 at the age of seventy-nine, never knowing these small pieces of the final chapter of her son’s life had survived the war.

On the far left flank, it had been more than an hour since Lieutenant Newhall was knocked to the dirt by German bullets. “I had been hit three times more and was lying flat on the ground with my helmet over my face,” he would later write. “Four of my men had dug a little trench nearby.” A couple dozen yards farther forward, the blood filling Pvt. Carl Fey’s mouth was gumming up, and his cheek was swollen and throbbing. Both lay stunned and helpless in the open field of shallow wheat stubble as the sun rose warm and bright overhead. But to the occasional Mauser pops and Maxim bursts was added the mounting crashes of enemy artillery fire, and Newhall and Fey lay helpless.

Back in the deeper wheat cover, rifle and automatic-rifle fire from Lieutenant Hawkinson and his dozen men had drawn scattered soldiers to his position, and his group had grown to about forty. Their digging with long-handled shovels “drew hostile artillery and machine-gun fire,” it would be reported, and twenty-two-year-old Cpl. Garner Herring of Mississippi, trying to provide covering fire with his rifle from the shallow hole he had dug, was killed instantly by a Maxim bullet. Short on ammunition, Hawkinson sent men low-crawling into the wheat to gather rifles and ammo from the dead, and he sent his platoon sergeant, Keron Ryan of Waterbury, Connecticut, running back through the shellfire to Colonel Ely’s command bunker to fix their position and request support. But an enemy machine gun traced the scrambling target, and somewhere in his hunched sprint back across no-man’s-land, Sergeant Ryan was shot in the back. He managed to shuffle back to his captain’s position and deliver his message before losing consciousness and dying.

* * *

A couple hundred yards to the right, Company K’s troops continued to dig in under punishing machine-gun fire. “Within the first five minutes 12 of the platoon were killed and four were wounded,” Lieutenant Morris would report. His men were digging the rear trench, still shallow and getting more and more crowded with soldiers leaping in for cover. Pvt. Joseph Zboran climbed from the packed trench onto the parapet. “Just as he got on the parapet he was shot with machine-gun bullets in the chest,” PFC James Chastain, still down in the trench, would later describe. Chastain asked Zboran if he was hit, he responded, “Yah,” then fell back into Chastain’s arms, “dying a few seconds later.”

Cpl. August Schmidt was trying to direct his squad to spread out and continue digging despite the torrents of bullets strafing the trench top. “The trench being too crowded he crawled out on the parapet,” a private would recall. “I told him he better get down, but he paid no attention to me.” Schmidt crawled farther down the line and was shot in his shoulder. “I’m hit,” he called out, but kept crawling, instructing his men to keep digging. “He had not gone very far when he was again hit with [a] machine-gun bullet, this time penetrating his left side and came out of his right side,” the private recounted. “He died instantly.”

Officers stood in the open, coordinating the consolidation of the new lines and directing their digging men, oblivious to the storm of gunfire. Lt. Irwin Morris stood behind the rear trench a few yards from Lt. Paul Derrickson, a tall, slender, twenty-six-year-old from Chicago. Both urged their platoons to keep down while digging. A bullet smacked Derrickson in the chest, and he called out, “Morris come over here and fix me up.” Morris, who darted over to him, later recounted: “He laid down with his head in his arms, and when I got to him he had passed away.” Paul Waples Derrickson was posthumously awarded both the Distinguished Service Cross and Silver Star. In the words of the accompanying citation, “Fearlessly walking up and down his line, he cheered and directed the work of his men until he was killed.”

With a distant low rumble followed by the hum of incoming shells, yet another layer of terror was added to the morning crucible. From his position near his platoon’s second-line trench, Lieutenant Morris saw his close friend Lt. Milt Drumm run back from an outpost and resume supervising his troops as they dug their front-line trench, when a shell blast knocked Drumm flat. As he had with Derrickson, Morris rushed to Drumm’s side, but saw that a chunk of shrapnel had gashed his head open. Drumm “lived only a moment or two” and “made no statements.”

Clarence Milton Drumm, twenty-eight, was a farmer from Bigelow, Kansas, who had filled his spare hours playing amateur baseball before America entered the war. He left his fiancée, twenty-five-year-old Linnie Booth, back home with the promise of a wedding on his return. Upon getting word that her beloved Milt was killed in action, Linnie wrote Lieutenant Morris, requesting the details of Milt’s death, filled with hope that “he was captured or is in a hospital wounded.” “There is no truth that could hurt any more than I feel now,” she explained. Morris doubtless wrote Linnie back, pressed into adding truth’s finality to her unbearable grief.

In the shallow trench still being dug by Drumm’s platoon, PFC Thomas Fursh tended the bullet wound of Pvt. Virgil Varnado, who had been struck by Maxim fire in his left leg while digging. “I opened my 1st aid packet and applied [the] bandage, but he was bleeding freely,” Fursh would recount. Before Fursh could apply a tourniquet, shrapnel from a shell blast struck Varnado in his forehead and arm, killing him instantly. Up in the outpost near the haystack, twenty-three-year-old Pvt. Raymond Branshaw, the company barber and “very well-liked by the boys,” was firing his Chauchat across the open plain toward the l’Alval Woods when a shell detonated near him. Lt. Si Parker checked on Branshaw, who was clutching a watch. Branshaw exhaled, “Here’s my watch, see that my mother gets it,” then died. Parker placed the watch in his pocket, and kept it until after the battle, when he ensured it was sent to Branshaw’s mother, Clara, back in Wisconsin. But after days of shellfire, Branshaw’s body was never seen again, and he is honored in the chapel of the missing.

* * *

Satisfied that the task of “mopping up” Germans from the village ruins was nearly complete, Capt. Clarence Huebner went up to the open ground in the orchard, where two platoons of his company and the machine-gun teams under Lt. Welcome Waltz were digging a slit trench for a strongpoint. His soldiers “immediately began to dig in and wire position, with the wire brought up by 5th Platoon, which was used as a carrying party,” Huebner would report.

Enemy artillery had been pounding away for a few minutes now, but most shells seemed to be falling out past the hedgerows and along the new lines being dug. From that direction, Captain Huebner noticed two men carrying a tall figure on a stretcher past his position, attended by more commotion than typically accompanied the evacuation of a casualty. The bearers laid down the stretcher on the dirt, and one of them ran to retrieve Huebner, who rushed over to discover that the wounded man was Lieutenant Colonel Maxey. His neck had been flayed open by a shell fragment, and though losing blood rapidly, he had insisted on being taken to Huebner to pass on detailed plans for the battalion’s mission.

“When I reached the colonel I found him upon the litter and helpless,” Huebner later recounted, “but he could speak and gave me full and complete instructions as to how to carry on.” Maxey directed Huebner to grab his map, and on it he showed him the cellar where his command post was being established, pointed out where he wanted defensive positions, and explained how best to man them. “All this time we were under heavy machine-gun fire with an occasional artillery shot,” Huebner noted, adding that the bleeding Maxey “showed utter disregard for his own wound and thought of nothing but the success of the operation.”

As Maxey was evacuated from the battlefield, Captain Huebner took the map and two runners back through the village then down into the dark cellar, where signalmen had just connected Maxey’s field phone to Colonel Ely’s bunker. Beneath the muffled din of the hostile world above, Huebner sent the runners to the new front lines to bring him back a progress report on consolidation. He then picked up the receiver, cranked the ringer, and intoned: “Maxey seriously wounded. I have assumed command. Am constructing a redoubt at 21.15. One strand wire around entire place. Casualties very slight. Will report complete as soon as messengers arrive from line. After completion will report.” The time was 9:08 a.m.

Outside Ely’s dugout, just a few minutes after getting Captain Huebner’s call, Maxey was carried up on a stretcher. It is unclear whether he was still conscious at this point, though the few surviving witness reports suggest that he was not. He was rushed to the first-aid station and then a field hospital, where all efforts to save him failed, and he died of his wounds by nightfall. Robert Jayne Maxey left behind a wife, Lu, and two sons, twelve-year-old Curtis and nine-year-old Ratcliffe. He was posthumously awarded both the Distinguished Service Cross and Silver Star, and after the war he was buried as he wished, in the West Point Cemetery.

* * *

On seeing the objectives taken and most enemy strongpoints conquered, the French tank commander, Capt. Emile Noscereau, gave the order to withdraw, and Schneiders lumbered back down the plateau, engines chugging but guns silent. Likewise, their work complete, flamethrower carriers drenched with sweat and blackened with ash and soot trooped out of the village and back through the former no-man’s-land. At 9:22 a.m., George Marshall picked up the phone in Ely’s bunker and phoned Brigade with a message for Division: “28th Inf. reports everything fine here—all objectives taken—work going on at rapid rate—getting well dug in—strongpoints established. Tanks have returned.”

Just over two hours into the battle, with tanks and flamethrower support gone, and with supporting French artillery exiting the sector in a constant stream, the Battle of Cantigny was now America’s to win or lose, a cause for which more than one hundred men had so far given their lives. And with the infantry dug in and no longer advancing, dispossessed of the initiative, the longest hours were yet to come.