By nightfall on May 29, the cost of taking and holding Cantigny was more than 1,100 men wounded and 250 killed. The heaviest casualties had been suffered holding the ground gained, just as George Marshall predicted. Seated in Bullard’s headquarters and still hobbled with a wrapped ankle, Marshall estimated the division’s total casualties so far at 600—half of the actual total. Down in that cellar, the few reliable casualty numbers and imprecise positional reports from the front could only piece together a blurred battlefield map. Even up in his bunker nearer the front, Colonel Ely, whose unheeded calls for relief had left him writhing with impotent rage for the past day, still had no handle on his regiment’s total losses, or the reality endured by his soldiers at the battle’s edge.

Eager for a firsthand feel, Ely sought and gained approval for “a personal reconnaissance in front of Cantigny.” After a starlit walk through the village ruins and a small part of the ragged, crowded front lines beyond—packed with wounded and lined with stacked dead—Ely returned to his bunker in a red fury. His jaw muscles pulsating, he picked up his field phone to relay a message to General Bullard: “Front line pounded to Hell and gone, and entire front line must be relieved tomorrow,” he erupted, adding he “would not be responsible”—presumptively for a German breakthrough. And he dispatched his intelligence officer, Lt. Joseph Torrence, back to General Bullard’s headquarters to personally push for relief.

A division staff officer who had been observing the battle from Colonel Ely’s bunker since Marshall had left the front the first night silently jotted notes in his small notebook, presumably for a later report to General Bullard. When he suggested aloud that the men could hang on longer, Ely exploded: “Let me tell you one thing and you can put it down in your little notebook. These men have been fighting three days and three nights and have been successful, but five of them are not worth what one of them was when he came in.” More than merely indulging in a passing rage, Ely calculated that restraint would be incapable of bringing attention to the conditions his men were enduring at the front. “It is an injustice,” he concluded, “not to relieve the men who have been fighting so long.”

A French plane was sent up in the clear night to check how the front lines were holding, and the pilot tapped out a wireless report: “line is unchanged.” Down in the trenches, Captain Huebner managed to get his 2nd Battalion troops some fresh water and food. “At night as soon as it became dark, details were sent back to fill canteens and bring up food,” one of his lieutenants noted. “Also the carrying party brought up ammunition and distributed it to the front line companies.” Up on the north end, Lieutenant Colonel Cullison remained in his command bunker a few hundred yards behind his 3rd Battalion troops, most reduced to defending their old pre-battle front lines.

Not far from the reoccupied German trenches, Lieutenant Newhall still lay half-upright, sunburned and dehydrated, cooped up in a ditch with the cold body of his dead corporal. With no rations or water left, he would die if he stayed put, and though he had no idea exactly how far back his company had withdrawn, he spent the first hours of darkness tapping his reserves of strength to make a break for the rear. “By midnight it was dark enough to move,” he later wrote. “I removed all my equipment and abandoned it, except my gas mask and helmet.” He fashioned a sling for his shattered arm out of his flare-pistol carrying case and forced himself upright. “The effort caused me to faint but I fortunately fell against the parapet and so remained upright.” Revived by the “cold night wind,” he muscled himself up and out of the trench and began shuffling back through the wheat.

In their outpost a couple hundred yards away, after a fruitless search for more canteens on the bodies of dead comrades, privates Gillespie and Drager were arriving at the same conclusion: help was not coming, and they would die if they stayed. With crushed legs and a gunshot wound in his back, Drager—possibly paralyzed—was helpless to move. But Gillespie, like Lieutenant Newhall, dug deep within and muscled his way out of the foxhole. “I put all my strength into the effort and found that I could move a little,” he noted. “Knowing that the old German second line trenches from whence I had come out were about seventy-five yards, I started in that direction, with the thought in mind that water could be found there.” As he began his shuffle back through the wheat stubble, Gillespie yelled back to his buddy Drager, “I’ll send back for you if I reach our men.” With lonely resignation, Drager exhaled, “There’s no need now, it’s too late.”

* * *

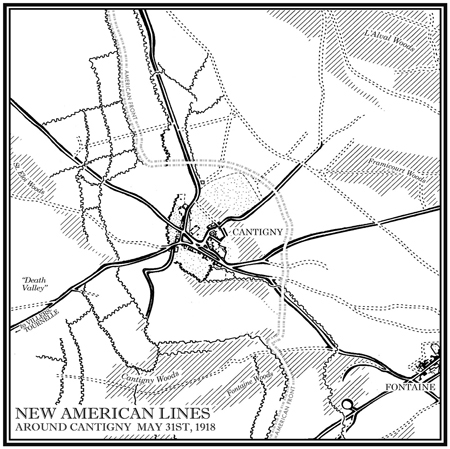

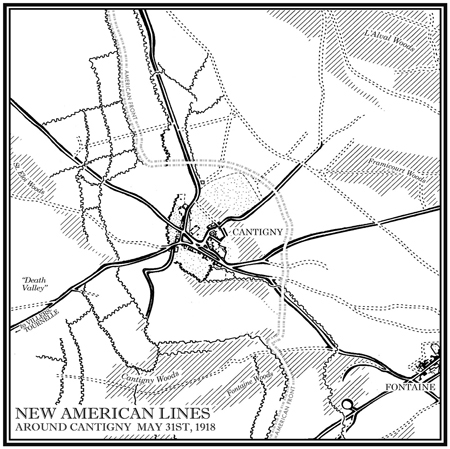

Over a mile away, Colonel Ely’s intelligence officer, Lieutenant Torrence, worked his way back to General Bullard’s headquarters on his mission to push for relief. The motorcycle messenger dispatched to meet him was killed by shellfire, forcing Torrence to walk through Death Valley back to Villers-Tournelle, where another motorcycle driver carried him the rest of the way to Division Headquarters in Mesnil-Saint-Firmin. He descended the stairs into the “old wine cellar underneath a chateau,” and found George Marshall on duty, with a handful of orderlies answering the phones. On hearing that Lieutenant Torrence had come directly from Ely’s command bunker with a personal request for relief, Marshall sent an orderly up to retrieve General Bullard.

Bullard entered, and as Torrence would later recount the scene, “asked Colonel Marshall if this officer had been fed.” The general’s thoughtfulness disarmed the keyed-up lieutenant, who noted, “It had been some three days since I had eaten anything except the reserve ration that I carried with me.” Bullard sent for the cook, who “prepared a wonderful breakfast” complete with “a bottle of wine.” Torrence delivered Ely’s clear message requesting—or if delivered equal to Ely’s tone, demanding—relief. Though Bullard’s reaction is not recorded, he must have left Torrence with the impression that this exchange spurred him to finally order relief. As Torrence would estimate in a letter to Bullard years later: “As a result of this contact with you my regiment was relieved the next night, which, I believe, saved a great many lives.”

But General Bullard had ordered the wheels of relief set in motion hours earlier, just after word of the late-afternoon counterattack had reached his headquarters. Even as Torrence was eating his midnight breakfast, reconnaissance teams from the 3rd Battalion of the 16th Infantry were trucking toward the front to prepare for relief, scheduled to occur the next night. To ensure the trenches would be thinned back down to reduce casualties in holding the new lines, Bullard ordered only two battalions—eight companies—to relieve the sixteen companies currently packed into the front lines.

These fresh soldiers had spent the battle in rest billets in villages miles behind the lines, and they moved toward the battlefront as wide-eyed and anxious as Colonel Ely’s doughboys had been at Zero Hour two mornings prior. Capt. Stuart Wilder, one of the officers leading a reconnaissance team, later described the scene as they crept through Death Valley, closer to the sights and sounds of war: “The valley was full of gas and bore the marks of heavy shelling … around [Ely’s bunker] many dead were piled; an aid station had been located in one of the entrances and wounded, who had died, and dead had accumulated there. The quarry was full of dead. All about was the wreckage of battle and the valley floor was well churned up by shellfire except close under the steep reverse slope.”

Captain Wilder and his battalion commander reached Colonel Ely’s bunker, where “It was immediately apparent that the situation in the front lines was obscure.” They made their way up the edge of the Saint-Éloi Woods, which “had been so heavily shelled that the woods were much thinned out,” and passed exhausted machine-gun teams, occupying “badly shot up” foxholes in the wood line. In his tiny, lantern-lit dugout, they found Lieutenant Colonel Cullison, who pointed out vague locations on his unfolded map, as if guessing his battalion’s lines. As Wilder would recount, Cullison “indicated the positions of the units on a map but it developed that he had never been over his battalion sector since the attack and was very uncertain of the location of his troops.”

Captain Wilder and a few members of his reconnaissance team ventured up the slope to find the jumping-off trenches and old front lines “overcrowded with men”—the thin remains of Companies L and K—“scattered without any apparent order.” And the doughboys there were as confused as their commander about their battalion’s lines. When another officer with the reconnaissance team saw what appeared to be movement out in no-man’s-land, he suggested the soldiers open fire. But they declined, admitting they were not sure if it might be one of their own. Their caution was wise—the movement came from a trench filled with the men of Company M covering the regiment’s open left flank.

* * *

A keen eye might have also picked out two other moving figures beyond the chewed-up barbed wire in the darkness of no-man’s-land. One was Lieutenant Newhall, expending his last reserves of strength to stagger nearer the division’s lines. His few-hundred-yard journey had so far passed in a blur, as he was driven to the ground every few steps by fainting spells or the tapping bursts of German Maxims. He had blacked out twice and lost his helmet at some point. “The only way I could move was upright which was dangerous because of the random machine-gun fire, but couldn’t be helped,” he noted; “Movement was slow and I had to crouch frequently for rest when I got dizzy.”

Newhall ran into ragged strands of barbed wire, a sign that he had finally reached the homestretch. “When I began to make my way through our wire, fortunately not very thick, I was challenged from our trench. They were suspicious of me for fear it was some German ruse, but finally allowed me to come in, and as soon as I could tell who I was [they] jumped out and helped me into the trench.” Newhall recognized them as members of Lieutenant Haydock’s platoon. “My first query was ‘had we taken Cantigny?’ My second was for a friend.…” He wanted to know where Haydock was, but the answer was written on their faces. “When I was told that he had been killed I went to pieces, and the sense of despair, which I can recall, I now recognize as grief. It has never been repeated by any other experience.” Newhall was taken back to the field hospital, then a Paris hospital, where he would spend the next few months deep in surgery, rehab, and grief for his best friend.

The other shadowy figure out in no-man’s-land was Pvt. Jesse Gillespie, crawling back toward the old German front lines, the ones Company K had captured and, for all he knew, still held. “Moving on my stomach caused such pain to my battered leg that I turned on my back, making use of both elbows and my left leg.” He found the trench and rolled in, finding it occupied only by the lifeless bodies of Captain Mosher and Lieutenant Drumm. His despair at finding the line abandoned was relieved only by water he was able to find in a few canteens. Panting and exhausted, Gillespie sipped some water and rested to regain his strength. At the first hazy signs of the coming dawn, he pulled out his pocket calendar, and crossed off May 30.

After getting word that his regiment would be relieved the following night, Colonel Ely decided the shot-up survivors of Company F—still under the leadership of their only surviving lieutenant—needed immediate relief, and he sent Company F of the 18th Infantry forward to replace them. He also moved another company of the 18th up to stand ready as regimental reserve in the old jumping-off trenches of 1st Battalion’s sector, empty since Company A had left them during the afternoon counterattack. When he phoned his decision up the chain—more as a pronouncement than a request for permission—he was told to “wait on Division.”

But Ely did not wait. Although earlier ordered to employ reserve companies only for counterattack and not for thickening the line, he unilaterally decided that replacement of an exhausted, decimated company with one fresh and full-strength was actually good preparation for counterattack and not, in fact, thickening. Ely would not have to lean on such nuanced interpretation long, as General Bullard reluctantly agreed within the hour to release two reserve companies to Ely, absolving him retroactively.

By the hour leading to dawn, the surviving, shell-shocked remains of Company F filed back through the orchard and across the former no-man’s-land for well-earned rest. They were replaced in the front lines by Company F of the 18th Infantry, whose captain and first sergeant immediately noticed unburied dead stacked behind the trenches. The captain organized a small detail to bury the dead “so that the sight of the bodies would not lower the morale of our men who were new to such conditions.”

The company’s four fresh platoons were still squeezing into the shallow trenches when enemy artillery opened up, giving the combat rookies immediate baptism by fire in the new reality of “such conditions” at the division’s crowded edge. Detonations crept closer and closer until a single, direct hit killed three privates, Patrick Barthelotte, Forest Johns, and Thomas Zangara, and wounded fourteen others. Their corporal, twenty-three-year-old Elmer Dommel of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, checked on them, but another shell struck the same spot, killing him instantly. That morning, all four were buried in the same shell hole, but after the war, none of their remains could be found.

Dawn was again greeted by German guns pounding the full length of the American lines. Up in Company M’s trenches north of Cantigny, shrapnel from a single mortar shell killed four men in a flash. Two of them, twenty-one-year-old Pvt. Conrad Malzahn and nineteen-year-old Pvt. Bernard Davidoff, both from Chicago, left no discernible remains. Down in Company C’s lines fencing the village’s southeastern edge, twenty-four-year-old Cpl. Sam Schmidt held his rifle over the parapet beside a member of his squad, Pvt. George Murphy. A whiz-bang struck in front of Schmidt, flinging him to the trench floor dead. Private Murphy ducked, and though showered with dirt, he was left unscratched. As their commander, Capt. Charles Senay, would later observe: “Battle, like baseball, becomes a matter of inches.”

The bombardment intensified, and the field telephone in Ely’s bunker began ringing as breathless runners started appearing at the entrance. Reports announced more shelling and urgently requested artillery support. At 3:30 a.m.: “enemy barrage came down on 1st and 2nd battalion sectors.” At 3:40: “Report of 3-star rocket from 1st and 2nd battalion.” At 4:25: “Shelling front line positions pretty heavily.” At 4:35: “Heavy corps artillery counter battery requested.”

Then the enemy shelling stopped all at once, the cue for German infantry to assault. Up in the front lines, doughboys could see two waves of gray-clad, rifle-wielding figures emerging from the woods. It was yet another counterattack, and as soon as flares shot up from the division’s front, Summerall’s artillery threw down a barrage. “[T]he first wave got through before our barrage was put down but was soon put out of action by infantry and machine-gun fire,” a captain in Ely’s bunker would record in the regimental journal. “The second wave was caught in our barrage and put out of action. Our losses slight. Enemy losses: a great many. No part of their line reached our first line.”

Again the Germans had counterattacked the Americans, and again the Americans beat them back. The 1st Division History would call it the enemy’s “final determined effort to retake the town”—an effort that was halfhearted at best. No fresh or additional troops were provided to strengthen the attack force; no protective artillery barrage was prepared to screen the infantry; and German records would refer to it only as “a feint attack.” After the now-familiar sight of a tide of field gray receding back into the woods, the guns fell finally quiet for a few hours.

By midmorning, a full-strength battalion of rested troops from the German 270th Reserve Infantry Regiment relieved the 271st and 272nd, which, after two full days of being ordered into suicidal frontal attacks on the new, thickly held American lines, were only skeletal units, with many rifle companies unable to muster even ten survivors. And with more and more manpower getting pulled into the German offensive at Chemin des Dames, General von Hutier’s forces could not afford to endeavor any more counterattacks against the stubborn Americans. No more attempts to recapture the prize of Cantigny would be launched.

* * *

For General Bullard’s 1st Division, the fight for Cantigny was over, the battle won. After that point, as one officer would later boast, “no German set foot in Cantigny except as a prisoner of war.” But for exhausted, parched, hungry, edgy, heavy-eyed men up in the trenches, the fight for survival continued. With no way of knowing the Germans had given up the quest for the village, the doughboys could only wait on another bombardment, or still another attack, knowing that up in these lines, with enemy artillery zeroed in on each new trench, death could still claim them at any moment.

Artillery on both sides pounded on through the overcast, gloomy day. The 1st Division Journal would note “heavy concentrations of 77, 88, 105, 150, and 210 caliber on Cantigny” in the afternoon alone, with more than 4,000 shells falling on American positions through the day, resulting in over a dozen more dead and twice as many injured. Summerall’s guns—which had collectively fired more than 30,000 shells the day before—continued firing 75s against enemy lines and hurling 155 shells into enemy battery emplacements, their task aided by the capture of a map from a German pilot shot down midafternoon near Villers-Tournelle.

By nightfall, as soldiers in the front lines chewed on their last bits of hard-tack rations and took turns catnapping and keeping watch, word that they were about to be relieved swept through their ranks with lightning speed. In his strongpoint, Lt. Welcome Waltz “very quickly, ran from one gun position to another” sharing the news with his Hotchkiss teams. “I had some difficulty in awakening them,” he noted, “for everybody was down and out, having been without sleep for three days.” Like most doughboys stuck for sixty straight hours in the same dirt, these men had reached the end of their physical tether, no longer capable of effective defense. “I doubt whether an enemy break-through at this time would have been seriously combated,” Waltz would admit, “for I don’t think the men would have awakened.”

* * *

In the old German lines conquered and abandoned two days earlier by Company K, Pvt. Jesse Gillespie had spent the warm day resting between slithering trips up and down the trench gathering water from the canteens of the dead. After darkness fell, the cool night air energized him, and he plotted a way back to the American lines. “[T]he thought came to me that I might use two rifles as crutches and be able to make better progress, advancing at night with such protection as the dark would give. I tried this scheme in the trench, but it did not work. My right foot dragged the ground in spite of all I could do, causing unbearable pain.” Desperate and running out of resources to sustain him for another long day trapped in the trench, he thought of cutting off his wounded leg. “I had with me a pocket knife with a blade about six inches long. I took it from my pocket and looked it over carefully. It was so dull from cutting tips, though, that I knew it would not do the job.”

As the hours crept closer to dawn, Gillespie grabbed a Colt .45 from the body of a dead officer, chambered a round and turned the barrel to his head. But he couldn’t pull the trigger. When asked years later why he didn’t, he responded that “the end of that pistol barrel pressed against my temple was as cold as a lump of ice. It cleared my brain and gave me the realization that maybe, after all, the time was not quite ripe for such a step.” As he dropped the pistol, his thoughts turned to his buddy, Willie Drager, whom he had left up in the outpost twenty-four hours earlier. Gillespie wondered if he was still hanging on, and whether help for either of them would ever come.

* * *

By midnight, help arrived for the platoons in the front lines as soldiers of the 16th Infantry shuffled across open ground, squad by squad, allowing Colonel Ely’s men to gear up, grab their rifles, and break for the rear in columns. In his strongpoint, Lieutenant Waltz was told to move his men back immediately and not to wait for relief. “I got them on the surface with their guns and equipment,” he noted of his machine-gun teams, who broke down their guns and heaved them back across the former no-man’s-land. They filed past the jumping-off trenches and old front lines and rested for a few moments before continuing the haul for three miles past Villers-Tournelle to Rocquencourt. “How we ever got our equipment back, I know not, but we did,” Waltz noted.

Wearied doughboys from front-line rifle companies filed back across the dark plateau, stepping carefully through shell craters and tall grass, occasionally tripping over scattered bodies. In one shell hole, troops encountered Pvt. Harry Heath, still hanging on after being shot through his hips and foot two mornings earlier just after Zero Hour. “I only went about 400 yards when I got bumped,” he noted. Since then, as with many other wounded soldiers, he had “laid in a shellhole two days and nearly two nights,” immobile, rationing his water and waiting for help. Now he was saved. Two men carried him back to the first-aid station, where he was patched up, then trucked to a Paris hospital, where he underwent surgery, leaving him “minus an inch or two of leg.” He would recover, but would forever walk with a limp.

War-weary, heavy-eyed soldiers, some with undressed wounds and all with strained nerves, dragged themselves from the battlefield and back toward Death Valley. “They could only stagger back, hollow-eyed with sunken cheeks, and if one stopped for a moment he would fall asleep,” Colonel Ely noted. Many who filed past the first-aid station were awakened to a scale of carnage they had not known in their small, closed-in worlds at the front. Bodies of the dead were stacked like cordwood, with streams of bandages hanging from stiff arms and legs—bloodied testaments to round-the-clock life-saving efforts by tireless medics. One private walking past later confided to his diary: “[T]here we found a great many dead Americans—piles of them—who had gotten back for first aid and after receiving it had died before they could be gotten to a hospital. In several cases more shells from the Germans had come over and blown them and the litters they were in into little bits.”

From there the battle’s survivors trooped back through Death Valley and a gauntlet of still more scattered blasts of German shells. But the men, having spent the past two and a half days backed up against their human limits, walked through without flinching. These few soldiers were the tried and tested, America’s first veteran warriors of a world at war. Back at billets they gulped down fresh water and a warm breakfast—“the first meal we’ve had in three days,” Cpl. Boleslaw Suchocki noted—then peeled off uniforms stiff with sweat and dirt, and collapsed like heaps into cots where they could finally find rest, quiet, and sleep. There was no flag-raising or operatic finale, just relief, which had come, in the words of one company commander, “[j]ust in time.”

Back at his headquarters, General Bullard typed out an official congratulatory statement he would send to Col. Hanson Ely: “The Division Commander takes great pleasure and feels it his duty to recognize, as much as in him lies, the gallant and efficient action and bravery of your regiment in the taking and holding of Cantigny for three days, May 28th, 29th, and 30th, under the most determined resistance and repeated counter-attacks of the enemy. Your losses in officers and men were large and the strain upon you very great, but you won.” In a triumphant message to War Secretary Baker, General Pershing reduced nearly three days of fighting to four words: “Well planned, splendidly executed.”

* * *

Up in the front lines, the doughboys of the 16th Infantry Regiment not tasked with improving the ragged trenches were assigned the grim job of burying the dead. Over the past two days of heavy fighting, the remains of the fallen, as one sergeant would report, had been “rolled in the nearest shell hole and covered up to keep down the odor from their bodies.” But many bodies remained out on the surface, stiff and bloated. Sgt. John Wallace “helped bury a number of bodies there that were in such condition as to make it impossible to identify them.” He reported burying a few the first night, then when he and his team ran out of darkness, burying “another bunch in the same hole.” A captain noted that because burials were “under heavy artillery and machine-gun fire, as conditions were, it was impossible to place markers on graves in any way … No identification tags were taken from the bodies.” As Sergeant Wallace would recount years after the war, “There are shell holes in Cantigny that I know had four layers of bodies buried in them and no markers were put up to show who or how many were buried there.”

The remains of the few fallen who had been carried back from the battlefield—and the wounded who had made it back alive but then died of their injuries—were added to the division’s makeshift cemetery near Villers-Tournelle. Just this fraction of the total losses in the two-and-a-half day battle doubled the temporary cemetery’s tragic ranks, providing a disheartening glimpse of the battle’s total cost.

Two days later, Colonel Ely submitted a regimental report based on the best information he then had, totaling the killed at 199 and wounded at 638. But his report accounts only for the 28th Infantry Regiment and does not include the total losses of the attached machine-gun companies, engineers, artillery, signal corps, medics, or any of the half-dozen reserve companies from the 18th and 26th thrown into the fight. And considering last-minute replacements, inaccurate morning reports prepared under the stress of battle, and many in the field hospitals who would still die from their wounds in the days and weeks following, an accurate total casualty count for the battle remains imprecise.

A search of all best available records, however, reveals the total cost of capturing and holding Cantigny at just over 300 men—either killed in action or later dying of wounds received in the battle—and approximately 1,300 wounded. And the French supporting the attack suffered their own casualties: a lieutenant with the tank battalion was killed by a sniper bullet to the head, and two members of the flamethrower section were killed. When considered beside the incomprehensible losses Allies had suffered in the mammoth engagements up to that point, the battle’s casualty total inappropriately seems small. But as Maj. Raymond Austin would write home, “Casualty lists of an attack like this don’t look very large beside those of a German 50 mile front drive, but when you see fine, young American boys lying dead in heaps of 6 or 8 or 12 here and there it’s more than enough.”

Even more elusive is a count of German losses. Swollen bodies of dead Germans filled Cantigny and the battlefield surrounding it. There were 275 bodies recovered from the village, and the number of dead that lay beyond the American trenches could only be estimated. Colonel Ely would report approximately 800 Germans killed, 500 wounded in action, and 255—including five officers—captured as prisoners of war. German records revealed a slightly higher number, reporting a total of more than 1,700 casualties, which left the entire 82nd Reserve Division with a “combat strength” only about 2,500 infantry.

* * *

On June 2, the same day as Colonel Ely’s report, after improbably hanging on to cross off two more days in his notebook, Pvt. Jesse Gillespie finally mustered enough strength to slither back toward the old American lines. “I prodded myself into action,” he noted of his inch-by-inch journey through the dirt. “Two hundred and fifty yards to go! Could I hold out?” He paused every few yards to catch his breath and find fleeting relief in the coolness he felt chewing on ripening wheat stalks. “With renewed strength and hope I hauled myself along until only thirty-five or forty yards separated me from my goal.” Through his dry, strained throat, Gillespie called for help, and ahead he spotted movement—a soup-bowl helmet, khaki—to his relief, “a fellow Yankee” from the 16th Infantry, who approached in caution clutching a pistol in one hand and two grenades in the other. Recognizing Gillespie’s uniform the soldier asked, “Can you stand for me to drag you in?” Gillespie whimpered, “I suppose I can, I’ve been dragging myself for several days.” After being carried to the first-aid station and getting a shot for lockjaw at the field hospital, Gillespie spent the next eighteen months in hospitals in Paris and Fort McPherson, Georgia.

That same night, when companies of the 16th Infantry moved forward under orders to straighten the “big jagged dent in the line” left by Lieutenant Colonel Cullison’s 3rd Battalion, a platoon found Pvt. Willie Drager lying in the same outpost Captain Mosher had ordered him and Private Gillespie and four others to hold five days earlier. Drager was dead, and likely had let go two days earlier, shortly after Gillespie had gone for help. The soldiers buried his body with the others in the foxhole, and after the war, at his mother Maude’s request, his remains were shipped back for burial in South Kaukauna, Wisconsin.

For the men holding on to the division’s new, exposed lines, life grew no easier, and over the next five weeks, battalion after battalion would take their turn riding out artillery bombardments and getting deadly reminders of enemy snipers and machine gunners that kept close watch on the sandbagged rim of the American trenches. As before the battle, patrols went out nightly to feel out the contours of a new no-man’s-land; a few companies launched raids on enemy lines; and casualties continued to mount at a daunting pace—more than 500 more men would be killed in action before the 1st Division was finally relieved from the sector on July 8.

* * *

Along the length of the Western Front, the war continued, though at a quickened pace. Kaiserschlacht rolled on full-steam gaining ground, and French defenses strained near collapse as the German Army approached the Marne River in a thrust toward Paris. With the question of American aptitude in battle answered loudly at Cantigny, General Foch again took up General Pershing’s offer for help. The very day Colonel Ely’s fighters were relieved from the front, the US 2nd and 3rd Divisions were sent into battle. The 3rd would support the French in a stalwart defense of the Marne bridges at Château Thierry, and at Belleau Wood two regiments of Marines from the 2nd Division would not only hold the line against wave after wave of violent enemy attacks, but would counterattack, purging German fighters from the thick woods with such ferocity, they would earn the nickname “Devil Dogs.”

By early July, with four corps formed, the AEF machine was finally operating near a capacity commensurate with Pershing’s vision. In mid-July, General Foch ordered a counteroffensive launched against the large German salient still pointed toward Paris, and when General Ludendorff launched the fourth stage of Kaiserschlacht in the same place, in Pershing’s estimation, it “played into the hands of the Allies.” Twenty-four French divisions and eight US divisions—including the “Fighting First” led by General Summerall after Bullard had been elevated to corps command—were in position and not only repelled the German attack, they pushed enemy lines back nearly to their pre-Kaiserschlacht positions in a victory Pershing would say “marked the turning of the tide.” It was here, German Field Marshal von Hindenburg would later admit, that his armies “lost the initiative to the enemy.”

In growing numbers and strengthened more and more by a tidal flood of fresh American troops landing in France at the rate of 250,000 per month, the Allies kept the pressure on the German Army, forcing Ludendorff to cancel the planned final stage of Kaiserschlacht. From that point forward, the kaiser’s forces would gain no more ground, able only to retrench between backpedaling retreats.

In early August, British forces in the north would attack the Germans at Amiens, pushing the enemy lines back over seven miles in a single day, one that General Ludendorff would call “the black day of the German Army.” By mid-August, General Pershing had enough divisions in place to form the First Army, a force of a half million troops—to include the 1st Division—which he employed in a successful assault on the enemy salient around Saint-Mihiel mid-September. So complete was victory there that General Summerall would note that the Germans “set fire to all of the villages in [their] retreat” and “saw that the war must be lost.”

Allied leaders joined to plan a knockout blow, a grand offensive in which British forces to the north and French and American to the south would advance “as nearly simultaneous as possible all along the Western Front,” with “each army driving forward as rapidly as possible.” The attack was launched on September 26, and again the American First Army played a pivotal role, grinding through strongly fortified enemy trenches from the Argonne Forest to the Meuse River. By the first week of October, German losses were so devastating that Field Marshall von Hindenburg cabled the German chancellor that “[t]here is now no longer any possible hope of forcing peace on the enemy,” and urging him to extend “an offer of peace to our enemies.”

While a flurry of diplomatic cables darted back and forth across western Europe, the Atlantic, and the English Channel, Allied forces continued forcing the Germans back on their heels with overwhelming speed. In what would become the largest battle in American history—and that Col. George Marshall would call “a wonderful and inspiring feat of arms”—doughboys helped purge the Argonne Forest and west bank of the Meuse of German defenders and kept advancing. By mid-October, Pershing had enough divisions in France to form a Second Army, the command of which he handed to General Bullard. By November, the First Army’s khaki legions had pushed the kaiser’s armies back more than thirty-two miles.

On the morning of November 11, Allied troops were still pushing forward when word of an Armistice reached front-line commanders: “Hostilities will be stopped on the entire front beginning at 11 o’clock.” Word of the end spread like wildfire among soldiers who, per their orders, kept pressing their advance until the second hands on watches and timepieces all along the Western Front clicked onto the eleventh hour. The moment caught the 1st Division waiting on open ground in corps reserve for an Allied advance toward Sedan across the Meuse River, and for them, news of war’s end “brought a confusion of incredulity and wonder.” Pvt. Frank Groves, who had served as a runner at Cantigny and subsequently survived fighting at Soissons, Saint-Mihiel, and in the Meuse-Argonne, later recounted the moment the guns fell silent: “On Nov. 11 at 11:00 a.m. those sounds and vibrations abruptly stopped. The quietness that followed was awesome; you could feel it—almost smell and taste it. There was no singing, no shouting, no laughter; we just stood around and looked and listened.”

* * *

Thus ended what was, to that point, the bloodiest war in human history: 8.5 million troops had been killed in action, more than 5 million on the Allied side. The United States, with more than 2 million military personnel in Europe by the Armistice, had suffered 116,516 killed, nearly all in the last five and a half months of the war. Of that total, the 1st Division had not only suffered the first casualties, but the most, with nearly 5,000 killed in action—more than 1,200 in the Meuse-Argonne offensive alone.

Though the doughboys of the Fighting First had fought in nearly every major Allied engagement in the final march to victory, they would be known not for their biggest success but for their loudest: Cantigny. Colonel Ely’s 28th Infantry Regiment would be forever named “The Black Lions” after the region’s coat of arms, and as a French Corps commander would declare in his commendation of the division: “[Y]ou, Sons of America, we are happy to call ‘The Men of Cantigny.’”

For the soldiers who survived the battle and then lived to fight the rest of the war, their experience served as a psychological battlement against whatever the enemy could throw at them. “I saw more hell in two days at Cantigny than in all the rest of the war combined,” Lt. Gerald Tyler would later write. The shellfire alone, George Marshall noted, “exceeded any experience they were to have later on in the great battles of the war.” And it was the division’s success in such a crucible that, in Marshall’s view, “demonstrated conclusively the fighting qualities of the American soldier.”

To be sure, benefits from the capture of the village were entirely local, and the strategic effect of the straightening of the small salient was almost inconsequential. But beyond battlefield consequences, victory at Cantigny had what General Pershing would call “an electrical effect,” as it revealed the AEF’s “fighting qualities under extreme battle conditions.” The win finally muted the voice of skeptics and gave Allied leaders confidence in the ability of the American soldier in combat. “Had it not been for Cantigny,” a 1st Division intelligence officer estimated, “the French would certainly not have entrusted a portion of the defense of the Marne to two other American divisions a week later.” It was a confidence revealed in the words of the London Evening News just as word of the American victory broke: “[T]he short story of Cantigny is going to expand into a full length novel which will write the doom of the Kaiser and Kaiserism.”

For the Germans, the loss of the village touched core anxieties about their American adversaries, especially after months of propaganda bent on coloring them in a contemptible light. The Americans had outsmarted them and outfought them, proving themselves a formidable enemy. A captured German officer would tell his captors: “The artillery and infantry work of your 1st division is worthy of the best armies in the world.” Years later, after retiring as a major general, Hanson Ely—who despite his later, larger victories would be known as “Ely of Cantigny”—assessed that his regiment’s victory “place[d] a scare” in the enemy: “To my mind the engagement at Cantigny was a cloud upon the German’s horizon that later meant defeat to their cause.”

* * *

Decades after the Armistice, on the verge of becoming the US Army chief of staff just as the world steered unwittingly toward an even larger clash of humanity, George Marshall rendered his own judgment on Cantigny’s place in history: “This little village marks a cycle in the history of America. Quitting the soil of Europe to escape oppression and the loss of personal liberties, the early settlers in America laid the foundations of a government based on equality, personal liberty, and justice. Three hundred years later their descendants returned to Europe and on May 28, 1918, launched their first attack on the remaining forces of autocracy to secure these same principles for the peoples of the Old World.”

A weighty verdict from the man destined to shape the battle lines of freedom in mankind’s two largest wars. Like Marshall’s words, the small battle inscribed on the narrative of the World War, in characters too bold to overlook, America’s place among the Allied nations. Now nearly a century gone, beyond the turmoil of a world at war, the fullness of time has enshrined the victory at Cantigny as an indispensable link in the chain of American destiny, and one small step, a mile over the high ground of a small French village, toward an end of the madness of total war.