The problem of species has long been familiar to analytic philosophers interested in Leibniz. Particularly in the treatment Leibniz offers of the problem in his Nouveaux essais sur l’entendement humain of 1704—a comprehensive response to John Locke’s Essay concerning Human Understanding of 1690—the problem has been understood principally as one in metaphysics and the philosophy of language: how it is, namely, that the meanings we give to words can be determined to capture the real natures of the things in the world that these words are purported to denote. What has been comparatively less studied is the problem of the determination of the boundaries of what we today would call “biological” species in Locke and Leibniz and the way in which this narrower problem gives rise for them to domain-specific problems that do not come up in connection with their respective investigations of the “species” of triangles, gold, or artifacts.

In the first part of this chapter we will see that Leibniz’s analysis of the nature and boundaries of biological species is very different from his now well-known nominalist account of the species of, for example, mathematical objects, and even of ordinary physical objects.1 With respect to plants and animals Leibniz positions himself squarely in the species-fixist camp, like his contemporary John Ray, the English naturalist who insists unequivocally that “the number of true species in nature is fixed and limited and, as we may reasonably believe, constant and unchangeable from the first creation to the present day.”2 Leibniz, like Ray, believes that all species were formed at the Creation and will remain fixed for all time, notwithstanding his simultaneous belief in the possibility of tremendous morphological change in a species over time and even of tremendous morphological change or “transformation” over the course of an individual creature’s life.

Whatever Leibniz’s views with respect to other ontological domains, such as that of mathematical objects, being a biological species fixist, Leibniz, we will see, is eo ipso a species realist, not a nominalist, at least if we understand nominalism as the view that groupings of individuals are arbitrary and not based on real shared kindhood; and realism, minimally, as the view that groupings are based on real, shared kind membership, rather than as the perhaps stronger view that kindhood is derived from the objective existence of a universal external to individuals in which these individuals participate. To believe that there is real kindhood requires at least the view that there are universalia in rebus in the sense often attributed to Aristotle. Leibniz’s nonnominalist account of biological species membership certainly does not take recourse to external, “Platonic” universals but could not get by without some presumption of a universal kind-membership inhering in the individual biological entities themselves.

Surprisingly, Leibniz maintains his species realism notwithstanding his well-known commitment to the principle of plenitude or to an infinite hierarchy of beings. In order for there to be a biological species between any two given species, there must be such a thing as species. For Leibniz, these are not species, moreover, in the sense in which Thomas Aquinas had understood the species of angels: that is, as singletons or sets occupied by only one member. Rather, a biological species is multiply instantiated, and to be a member of the same species as another creature is to share in the same line of descent from the same ancestors as that other creature. A biological species is for Leibniz a relatively isolated reproductive community, all of whose members may be said to be members of the same species not in virtue of any morphological resemblances (though they generally have these as well) but rather in virtue of shared origins.

This account of species, while starkly different from Aristotle’s, is one that came by the sixteenth century to be associated with Aristotle’s biology and that emerged out of the combined impact of the exigencies of the new science of taxonomy, particularly botanical taxonomy, together with a new tendency in scriptural interpretation to read Genesis as describing the original, true, and regrettably lost system of classifying living kinds.3 Leibniz is very much of his time, a contemporary of John Ray and a taxonomical thinker squarely in the line of development that extends from Andrea Cesalpino in the sixteenth century to Linnaeus in the eighteenth.

An important part of the story of the emergence of modern species fixism, though one that cannot detain us for long here, has to do with developments in the history of scriptural interpretation. Many sixteenth-century naturalists came to believe that Adam’s legendary ability to discern essences was recoverable, and indeed would be recovered by their own research.4 To cite one of many examples, in his Neu Kreutterbuch (New Book of Herbs) of 1577 Hieronymus Bock writes that “it is . . . clear and undeniable that Adam, as the first-created, did not only clearly and correctly understand all of Earth’s creation through the pouring in [to him] of divine power and wisdom, but also named every creature with its correct name.”5 There is a remarkable similarity between reflections such as those of Bock on the one hand and those we find in texts on the biblical languages on the other.

As we will see later in this chapter, Leibniz’s interest in finding and classifying paleontological kinds is for him of a pair with his lifelong interest in the tracing of the linguistic histories of nations, and he brings an antiquarian zeal to both of these projects. But while he is ardently fixist with respect to animal kinds, living or extinct, he is also, so to speak, a staunch evolutionist with respect to language. For this reason, Leibniz is skeptical of the very idea of a primordial Adamic language that would give the true names of things. He believes instead that many languages, including Hebrew but also German, have something “primitive” about them, in the sense that the names for things are rooted in natural sounds associated with them. But beyond this there is nothing particularly primordial about any language, scriptural or national.

As already mentioned, for Ray the number of species was fixed once and for all, and variation within a species, much as for today’s “creation scientists,” could never lead to transmutation. Thus he writes in a 1696 text:

Differences that issue from the same seed, be it in an isolated plant or in an entire species, are accidental and not the signs of a specific character. . . . The same is true of the animal world . . . the number of species in nature is certain and determined: God rested on the sixth day, interrupting his great work—that is, the creation of new species.

Although species are eternal, for Ray their essences are unknowable:

The correct and philosophical division of any genus is by essential differences. But the essences of things are unknown to us. Thus, in place of these essential characters, characteristic accidents should be used . . . [that] join together plants that are similar, and agree in primary parts, or in total external aspect, and which separate those that differ in these respects. . . . The essences of things are wholly unknown to us. Since all our knowledge derives from sensation, we know nothing of things that are outside us except through the power that they have to affect our senses in some particular way, and by the mediation of these impressions to cause a particular image to arise in the intellect. If the essences of things are immaterial forms, it is admitted by everyone that these are not encountered in any sensible means.6

Ray believes that species are “Ideas” in the divine mind, and denies any true transmutation, admitting only what we might describe as microevolution or intraspecies phenotypic drift. He maintains that biological kinds “are not transmutable, and the forms and essences of these are either certain specific principles, that is, certain very small particles of matter, distinct from all others, and naturally indivisible, or certain specific seminal reasons enclosed by means of an appropriate vehicle.”7

The ontology and epistemology of biological kinds defended by Ray would prove a difficult pair to sustain together. If essences cannot be known, then one might reasonably protest that we have no good reason to think there are such things. In contrast to Ray, many others, influenced by currents of thought as diverse as Epicureanism, Baconianism, and Skepticism, would come to sense the tension between the skeptical epistemology and the realist ontology that Ray hoped to rope together. John Locke’s nominalism, to cite an important figure in the emergence of Leibniz’s mature views on species, may be seen in large part as a consequence of the evident inability of biological taxonomy to adequately reflect the complexity of its object of study.8 Locke discerns a deep theoretical as well as an empirical problem. If essences are wholly unknown to us, as Ray acknowledges, then how do we justify our classificatory systems except as arbitrary reflections of our narrow priorities? That is the theoretical problem. The empirical problem is this: if species, whose essences are unknown to us, are set down for all eternity at the creation, how do we account for the abundant cases nature appears to present to us of overlap and hybridity? How do we account for what John Dupré would later describe as the ineradicable “disorder of things”?9

Early modern nominalism partially maps onto what is today sometimes referred to as “species antirealism” in the philosophy of biology.10 According to this latter doctrine, because what we think of as species are but snapshots in time of various, ever-evolving lines of descent, there can be no justification for treating biological species as real natural kinds. Today’s antirealism is strongly motivated by evolutionary theory (though, to be sure, many evolutionists remain realists), which takes animal species out of the class of relatively stable, fixed entities, like the elements on the periodic table, and historicizes them, placing them more on a par with, say, nation-states or car models. The nominalism associated with, for example, Locke, has something of a different focus: it is not concerned with whether some kind has a changing history or is fixed and unchanging. Rather, it is motivated by the recognition of the impossibility of ever getting, by empirical means, to the real essence of a thing. The only sort of essence that may now be spoken of is the nominal essence, which may be determined in view of the powers a thing has or the way it enters into relations with things outside it. Thus, for Locke, in an important sense biological species do not present any particular problems that do not also arise in the case of, say, the elements.

Yet it would be difficult not to notice that Locke is relatively more preoccupied with the status of biological species than with other purported natural kinds,11 particularly with human beings and those primates most closely resembling them. Indeed, at times he appears to believe that the best empirical evidence in favor of his nominalism comes from what he takes to be the common natural phenomenon of cross-species reproduction. “I once saw a Creature,” he maintains,

that was the Issue of a Cat and a Rat, and had the plain Marks of both about it; wherein Nature appear’d to have followed the Pattern of neither sort alone, but to have jumbled them both together. To which, he that shall add the monstrous Productions, that are so frequently to be met with in Nature, will find it hard, even in the race of Animals to determine by the Pedigree of what Species every Animal’s issue is; and be at a loss about the real Essence, which he thinks certainly conveyed by Generation, and has alone a right to the specifick name.12

When, as was discussed in chapter 6, reproduction was conceived by premodern science as the imparting of a form that endows the offspring with some real essence, there was little problem in accounting for the ontological status of species, or in asserting with certainty the membership of an individual within a species. The mechanization of embryogenesis, which is to say first and foremost the removal from this process of a role for a formal principle, effectively put all species on the endangered list, so to speak, and threatened to give us only a world of individuals. This is precisely what Malebranche feared, as we saw in chapter 6, when he adopted the imagination theory “to explain why a mare does not give birth to a calf, or a chicken lay an egg containing a partridge or some bird of a new species.”13 Yet what Malebranche feared, Locke would soon celebrate.

Nathaniel Highmore, to cite another revealing example, confirms the point that, for many, purely mechanistic embryogenesis threatened to bring about a crisis in the traditional understanding of species. In criticizing Kenelm Digby’s strict mechanist account of generation in terms of the operations of “external accidents” working upon intrinsically inert particles, Highmore wonders, assuming that there is “nothing else to give a figure to Plants, but ascending and descending, of light and heavy parts,”

whence should that variety arise in the fashion of those ascending and descending parts: the weight of the parts should carry them directly downwards, as the lightness doth upwards; and so all roots should descend in one continued round, but long, lump: what then makes some spherical, other stretching out infinite numbers of hairy threds; some directly downwards, others parallel to the superficies.14

In short, mechanism might be able to account for generation in general but not for the generation of all the diverse kinds of creature. Here, the example concerns plants, yet, as Highmore goes on to note, “the formation of Animals affords us little lesse perplexity.”15

As we have already seen, Descartes denied the end-directedness of natural phenomena, including embryogenesis; but it would not be until the second half of the seventeenth century that the link between this denial and the tenuousness of species would be made explicit: the end-blindness of nature now means that the tendency of horses to beget horses is no more natural than the occasional cat-rat, ape-man, mule, or monstrous mola. Even if Descartes never faced up to the problem, for Locke mechanism cannot but militate in the direction of antiessentialism; in the domain of science with which we are concerned, this means that the revolution in embryology that brought about the abolition of formative faculties also brought about a crisis in the concept of biological species. For Locke, the mechanist ontology underlies the theory of classification. As Michael Ayers has noted, Locke’s mechanism holds that all changes in nature are just changes of degree—anything that is not an atom is infinitely malleable.16 This means, among other things, that the difference between two horses on the one hand and a horse and a zebra on the other does not give us any instruction as to how to go about classifying. Thus, horses are grouped together, and zebras are excluded, but this is a pragmatic decision, not one dictated by reality. We classify in a manner dictated by differences that matter to us, and this is an appropriate approach to classification because differences between things come about not as a result of differing essences but only of rearrangements of atoms.

Leibniz’s response to Locke’s position would be both innovative and conservative. His ultimate concern would be to hold onto the reality of biological species while acknowledging the difficulties Locke discerns in coming to know the true natures of things and in establishing the true criteria for grouping similar things as separate instantiations of the same thing. Leibniz would ultimately come to adopt a fairly nominalist view of the objects in certain ontological domains (indeed, the ontological domains that have tended to garner most of the attention of historians of philosophy). But for him, in contrast with Locke, biological species do present a number of particular problems that are not there in the case of, for example, gold or mercury, let alone of mathematical objects, and therefore require a separate analysis. Let us turn now to Leibniz’s analysis of biological species.

As we have already seen, for Leibniz identity runs deeper than kind-membership. As shown by the examples, already considered in chapter 5, of Heliogabalus’s reincarnation as a pig, of insect metamorphosis, and of the promotion of a bare monad to spirit at conception, for Leibniz an individual can change from one kind to another, while (other than in a few passages that we shall consider shortly) a kind itself cannot change into another kind. Leibniz writes in the Nouveaux essais, for example, “there are kinds or species to which an individual could not (naturally, at least) cease to belong, once that individual has already belonged to it, whatever revolutions may come to pass in nature. But there are kinds or species that are (I admit) accidental for the individuals that belong to them, and they may cease to be of that kind.”17 But which are the species that an individual cannot leave behind, which are the accidental ones, and what accounts for the difference? The view that an individual can pass through various species is sometimes called “transformism,” and it is particularly widespread among Platonically inclined philosophers of the early modern period. These thinkers tend to see individuals as the bearers of essences, and they take these essences to be so durable that they could survive even the transition of the individual from one species to another. Some features of early modern transformism may be traced in part to the discovery of microorganic life, together, perhaps, with the resurrection or continuation of ancient ideas about change, best captured poetically in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. To cite one example, Anne Conway argues in her Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy, published posthumously in 1690, that all creatures are mutable in respect of their natures, and even that “the justice of God gloriously appears in the transmutation of things from one species to another.”18 This transmutation is not substantial but only modal, in the sense that while changing the species or nature of the creature, the essence remains the same, which is to say for Conway that it remains the same creature through its various species transmutations. A creature’s species, then, would appear to be just a stage of it. As Leibniz explains similarly in a letter to Thomas Burnet: “I maintain that there must always be a preformed living being, be it a plant or an animal, that is the basis of the transformation, and that the same dominant monad must be there.”19

Conway takes insect metamorphosis as confirmation of transformation as a general principle of nature and includes as instances of the same principle at work a number of rather unexpected phenomena, including “spontaneous” generation: “Among animals, worms change into flies, and beasts and fish that feed on beasts and fish of another species change into their nature and species. And does not rotting matter, or body of earth and water, produce animals without any previous seed of those animals[?]” While transformation is generally described in terms of the striving of creatures toward, or falling away from, God, Conway also sees this process as, at least sometimes, influenced by environmental factors: “Just as wheat and barley can change into each other and in fact often do so, which is well known to farmers in many countries, especially in Hungary where, if barley is sown, wheat grows. And in other more barren places, and especially in rocky places such as are found in Germany, if wheat is sown, barley grows instead, and in other places barley becomes plain grass.”20

Leibniz seems to assume that the transformations of individuals will unfold in a relatively stable way in virtue of the kind of thing they are, and will remain, across their transformations. That is, caterpillars regularly transform into butterflies, but not into fish, and this in virtue of the fact that they are in all their stages preformed descendants of a biological kind that includes all the members of, for example, Morpho menelaus. In this respect, as we already saw in the previous chapter, Leibniz is a very conventional defender of heterogenesis in that he, like Athanasius Kircher and others, seems to believe that there are clear rules governing which kind of creature can be transformed into what, as for example in the case of what was sometimes called “taurogenesis,” in which a rotting ox carcass gives rise to bees, but never any other variety of insect.

Transformism, then, is nothing like a Lamarckian account of change in lineages as a consequence of the change of individuals in response to their environment. Conway and Leibniz both believe that what transforms over time are not lineages but rather individual creatures, which are immortal, and that these transformations happen for reasons that have more to do with the creature’s relative spiritual “excellence” or worthiness than with natural factors. For Conway and Leibniz both, transformism is of a pair with what might be called “gradationism,” the view that there is a “chain of being” extending from the “lowest” creatures (worms and such) at the bottom to angels and then to God at the top, with human beings the highest in the chain among earthly creatures.21 This conception of the order of nature is rigidly hierarchical, and a creature’s position in the hierarchy is determined by one criterion, its perfection, which is to say the degree of its likeness to God. Leibniz’s particular version of the chain of being has it not just that there is a hierarchy of kinds, but indeed that between any two kinds on this hierarchy there must be an intermediary kind. Yet the infinite gradations of species of varying degrees of excellence need not push in favor of a nominalist interpretation of Leibniz’s theory of biological kinds, since, again, in order for there to be a kind between any two given kinds there must at the very least be such things as kinds. Although the hierarchy is conceived as a continuum, nonetheless it must have some abrupt breaks, since some of the characteristics that define species, notably reason, are all-or-nothing affairs. Either you possess reason or you do not, and to open up the possibility that reason could be possessed in greater or lesser degrees is to open up the possibility that human beings are nothing special among natural beings, that nonhuman apes, for example, could possess in some degree what humans possess more perfectly, and indeed what makes them human.

The principle of the plenitude of natural kinds is therefore not entirely analogous to the principle of continuity that describes, for example, geometrical lines or the set of real numbers, since in the latter case it is key that there are no real elements composing a continuous line, whereas there are real, multiply instantiated kinds within the hierarchy of kinds. We should therefore not be too tempted to see Leibniz’s commitment to the principle of plenitude as strengthening the case for his nominalism, since in fact he holds that the belief in a kind between any two kinds does not exclude the possibility of real, abrupt breaks. The scale of beings may more correctly be said to be dense than continuous, in the modern mathematical sense of having actual discrete units between any two given units.

One compelling ground for ascribing biological nominalism to Leibniz may be the extent to which he seems to agree with Locke about the difficulty of getting to the characteristics that truly mark off one kind of being from another—to its “real essence,” in Locke’s terms. Thus, for example, Leibniz writes in an important letter to A. C. Gackenholtz of April 23, 1701 (see Appendix 5), that there is always a variety of ways to classify in any domain of science. Citing his own De arte combinatoria, of 1666, which he proudly mentions having written as an “adolescent,” Leibniz notes that in any domain “the genera of any determinate number of inferior species correspond to the combinations of things, so that it is understood that there are as many combinations of things as there are kinds of species.” He notes that philosophers and jurisconsults have studied the variety of moral virtues by considering the different ways of subdividing them. Yet in these cases, as in the case of biological kinds, “since there is an immense variety in the great number of combinations and in the various ways of separating them, it is apparent that, if the method is to be of any use, the more useful comparisons will be preferred; as also for the sake of aiding the memory, a method that is more detailed and more commodious may be preferred.”22 Classification is then arbitrary and based on what interests the classifier. Yet it is important to bear in mind that here Leibniz is concerned with the classification of species into higher genera and not of individuals into species. Since Leibniz is working in a preevolutionary context, the classification into higher taxa can have nothing to do with charting lines of descent or with kinship. Indeed, since there are no real kinship relations among species, it might be thought that classifying into higher kinds can only be based on criteria that are initially chosen in view of some special human concern or other. Yet Leibniz believes that one can discern real “analogies” or “resemblances”23 among species, even if these do not come from shared descent.

Presumably, this reality derives from the proximity of the blueprints of two species in God’s mind at the Creation. The taxonomic grouping of several species into a genus, then, should ideally reflect this proximity, even if it is difficult to pick out the right morphological features in virtue of which two species may be said to be objectively close. Some plants have similar roots but very different flowers; other plants might resemble one another in their flowers but have a very different root structure. Leibniz notes that the current fashion in botany is to prefer classification based on flower morphology, and he is skeptical but not entirely dismissive of this approach, for reasons we will consider shortly.

Leibniz notes in the same letter to Gackenholtz that in botany divisions are generally made either with respect to the particular usefulness of the plant for human beings, or with respect to the plant’s morphological features. Both of these criteria are accessible, Leibniz notes, without any particular grasp of the “interior” nature of the plant. But, he goes on, there is no reason to despair of not being able to access this interior nature, since as a result of the work of Jungius, Malpighi, Hooke, Swammerdam, and Leeuwenhoek, “soon we will arrive at something more profound” in our study of plants.24 He concedes that classification with respect to the flowering part of the plant may be more profound than any other morphological criteria, since “there is in fact a very great connection between the flowers and the generation of the plant; and it is above all useful to find the variety of principles in generation; which Aristotle himself saw when he undertook to trace the variety of animals back to this capital point.”25 Leibniz repeats in an undated text published a few years after his death in the Otium hanoveranum that botany must not be limited to the study of the medicinal effects of plants, but must extend, most importantly, to the study of their reproduction: “Botanists are complacent in the mere noting of plants and their virtues. Few take an interest in the growing of plants for the purpose of the propagation and conservation of seeds.”26 While one must consider multiple ways of classifying, ultimately it is the flowers, as the part most closely connected with generation, that serve as the best indicator of species.

For Leibniz, there is nothing wrong with employing multiple systems of classification. Indeed, the more the better, as each one may help to reveal something new about the structure and nature of the entities in question. What is more, a perfectly acceptable principle of classification might for Leibniz be simply pedagogical, where entities are placed together not in virtue of any real belief in their kinship, but only because, so arranged, it may be easier to learn their names. Leibniz does not see anything wrong with this. Yet in the end the study of the flowering part—by which Leibniz means not the petals of a flower but the reproductive parts enclosed by the flower—is (probably) going to be the most revealing about the true nature of the plant.

He sums up all of these points in a rich passage of the Nouveaux essais. The modern botanists, he maintains,

believe that the distinctions taken from the forms of the flowers best approximate the natural order. But here as well they find much difficulty, and it would be relevant to make comparisons and arrangements not only according to one criterion, such as the one I just mentioned, which is taken from the flowers and which is perhaps the most fitting up until now for a system that is tolerable and commodious for those who are learning, but also according to other criteria taken from other parts and conditions of plant: each criterion of comparison warrants its own separate Tables [of classification]; without which we will allow to escape our attention many subordinate genera, and many comparisons, distinctions, and useful observations. . . . The more one follows the arrangements and conditions that are there required, the more one approximates the natural order. This is why, if the conjecture of certain notable people turns out to be correct, that there is in the plant, besides the known grain or the seed that is analogous [qui repond à] to the egg of the animal, another seed that could be called masculine, that is to say a powder (pollen, which is very often visible, although perhaps sometimes invisible, like the grain itself of certain plants), which the wind or other usual accidents spreads so as to join it with the grain which comes sometimes from the same plant, and still other times (as is the case with hemp) from a neighboring plant of the same species, which by consequence will be analogous to the male, although perhaps the female is never entirely deprived of this same pollen.

Leibniz believes that by paying attention to these generative elements within the flowers, eventually we will be able to come to the “natural divisions” of botany, that is, to a classification of plant kinds that maps onto the real differences between species:

If (I say) this turns out to be true, and if the manner of generation of plants came to be better known, I do not doubt at all that the varieties that we would discern would provide a criterion for very natural divisions. And if we had the penetration of some superior intellects and knew things well enough, perhaps we would find there attributes fixed for each species, common to all of its individuals and always subsisting in the same organic living being, whatever alterations or transformations might befall it, as in the best known of physical species, which is the human, reason is such a fixed attribute, which pertains to each individual and always inseparably, even if one cannot always perceive it.27

In Leibniz’s account of the importance of the reproductive parts of plants for determining their true natures, the perpetual motion of reproduction, or self-propagation through the generation of offspring (from preformed primordia, of course), lies at the heart of the account of what it is that makes a biological entity the kind of entity it is. That is, he believes we should study the reproductive parts of flowers if we want to know what kind of plant we are dealing with, since it is in large part through reproduction—rather than, say, the growth of thorns—that the perpetual motion machine that is the plant perpetuates itself, or, in other words, keeps its species in existence.

This account agrees with the theory of species realism and species fixism that, rightly or wrongly, came in the early modern period to be attributed to Aristotle. On this account species membership is determined exclusively through lines of descent: to be a member of a kind is to be descended from the original parents of this kind. In the lengthy passage just cited, Leibniz acknowledges the strength of the theory of species membership that sees this membership as rooted in descent from common parents alone. He maintains that because an animal is a machine of perpetual motion in part in virtue of its capacity for self-reproduction, classification of species in terms of their generative systems is less arbitrary than any other taxonomy based on the comparison of morphological features. Creatures are the creatures they are in virtue of their being generated from like creatures, and they bear real relations to members of other species in virtue of resemblances of their generative systems. This is what Kant would later call “the unity of the generative power,”28 that is, the inclusion of a group of scattered individuals in the same kind in view of their shared ancestry.

In the Nouveaux essais, Leibniz expresses agreement with the principle, defended by Ray and others, that shared species membership may be determined by looking at lineages of shared decent. As he writes, in cases of doubt, “generation or race”—a curious synonymy to which we will return later in this chapter—“gives at least a very strong presumption” as to the creature’s species membership.29 Whatever views he might hold as to the reality of mathematical or other kinds, with respect to biological species “it is the nature of things that ordinarily fixes the limits of species.”30 In effect, the nominalism that we might wish, along with Benson Mates and others, to attribute to Leibniz with respect to mathematical objects, and perhaps even to physical objects, cannot be extended as far as biological entities. For, as Leibniz explains very clearly in the Nouveaux essais, different meanings attach to the notion of species depending upon the ontological domain in which it is being applied. Leibniz writes: “There is some ambiguity in the term species or being of a different species; which is the cause of all these confusions. . . . We can understand species either mathematically or physically. In mathematical rigor the slightest difference that brings it about that two things are not entirely similar, brings it about that they are of different species.”31 He goes on to consider the differing cases of three different kinds of mathematical object: the circle, the ellipse, and the oval. There is only one species of circle, since all circles resemble one another perfectly. There are infinite species of ellipses, but only one genus, since in all ellipses the ratio of the focus and the apex differs only with respect to size. In ovals with three foci, finally, there are infinitely many species and genera.

Now, in physical entities, since no two ever resemble each other perfectly, it follows that by the same criteria as those employed with respect to mathematical entities, every individual entity is isolated from every other with respect to species. Moreover, since every physical entity is constantly changing, no individual thing ever perfectly resembles itself, and thus “men laying down the physical species do not adopt such a rigorous stance and it depends on them to say whether a mass that they can themselves make to return to its original form remains in their view the same species. Thus we say that water, gold, quicksilver, common salt remain the same and are only disguised as a result of ordinary changes.”32 However, the criteria for plants and animals are not arbitrary in this way. Leibniz continues: “But in organic bodies or in the species of plants and animals we define the species through generation, so that this similar being, which comes or could come from the same origin or seed, will be of the same species.”33 In contrast with mathematical identities, and in contrast with ordinary physical entities, the criteria for establishing sameness, or sufficient sameness to be included in the same species, are not based on arbitrary or subjective concerns of the person who classifies living beings but on the objective fact that all the members of the same species of living beings have the same origin.

For Leibniz the animal is not just a machine of perpetual self-nutrition and self-reproduction, as we saw in chapter 2. It also has its own “special office” (officium) that makes it a member of the species to which it belongs. In contrast to Locke, and indeed to Ray, Leibniz believes that we may eventually come to know the special offices of all animals.34 He acknowledges that outside of the human species—of which we know that all members have the special office of contemplation not by study of human morphology but through direct experience—our knowledge is limited. Yet he also believes that any limitations here may in principle be overcome.

In the Corpus hominis of the early 1680s, Leibniz asserts explicitly that “machines do not have a species,” but here he clearly means only machines in the common sense. Animals are for him those machines that do have a species, which is discernible in their trademark activity, and which is maintained through their motion and reproduction. It is of the essence of a squirrel to dance or jump, so a squirrel is, essentially, a dancing or jumping machine. The need to see this trademark activity in order to grasp the true nature of the species is one reason why ethology must be included along with anatomy and physiology in any adequate science of animal economy. In the letter to Gackenholtz of 1701, Leibniz makes this very clear. Plants and animals, he writes, “and, in a word, organic bodies produced by nature, are machines able to perform certain offices, which they do in part through their individual nutrition, in part through the propagation of their species, and finally also through their very perfection, that which each one brings about through its special office.” Leibniz goes on from here to make explicit what that “special office” is in human beings: a human being is “a machine for the perpetuation of contemplation,” just as a squirrel is a machine for the perpetuation of dancing or jumping.35 Leibniz had already written similarly, in the Specimen inventorum de admirandis naturae generalis arcanis (Specimen of Discoveries concerning Admirable Secrets of a General Nature) of around 1688: “Therefore it is well enough that souls be given to brutes, especially as the bodies of brutes are not made for ratiocination, but rather are destined to various functions; thus the silkworm is made for weaving, the bee for making honey, and others to other functions through which everything in the world may be distinguished.”36

How can Leibniz be so sure that we are capable of coming to know the real special office of a creature and not just some feature that is phenomenally salient from a human point of view? The short answer is one that extends far beyond the bounds of his philosophy of biology and into his physicotheology and theodicy: Leibniz believes the various species of animals were created for us in the first place. Their special offices are special principally for us, but at the same time, in Leibniz’s anthropocentric world, an animal’s being-for-us, so to speak, is its being tout court. Coming to know it through its salient features is the same thing as coming to know it. In this respect, Leibniz simply ignores the epistemological problem that served as the engine of doubt in Locke’s nominalism and indeed in so much modern philosophy. At least with respect to knowledge of biological kinds, Leibniz remains a very premodern philosopher, one who believes that God simply would not place us in a world of essences from which we are cut off by some epistemic gap.

Leibniz continues in the 1701 letter to Gackenholtz:

In other bodies [besides the human body], the whole purpose of nature has not been adequately explored by us. However, it is not at all doubtful that a great part of its purpose lies in human usage, which is to say auxiliaries that aid in our contemplation, or, which is the same, that excite in us admiration of the divine wisdom.37

This belief, while theological, has important epistemological consequences. One is that, for Leibniz, in contrast with Locke, real essences can be known; indeed, the real essence of a species is that feature that serves both as a sign to humans of God’s wisdom and as the very reason why God created it in the first place. A natural-philosophical consequence is that, in order to hold to the view that creatures are designed for the very purpose of disclosing to us God’s wisdom, Leibniz must ipso facto also hold that creatures are designed, that is, that their organs were formed for the execution of some function rather than that functions are executed by animals because they happen to have the right organs. Leibniz beseeches his readers already in the Discourse on Metaphysics of 1686 to “keep away from the phrases of certain extremely pretentious minds who say that we see because it happens that we have eyes and not that eyes were made for seeing.”38 One of these pretentious minds may be Spinoza, who in the Appendix to Part I of the Ethics argues adamantly that we chew because we happen to have teeth, rather than that we were given teeth in order to chew. Other likely culprits here are the various neo-Epicureans of Leibniz’s day who were keen to resurrect the Lucretian account of the origins of species out of fortuitous arrangements of atoms.

As we have seen, an animal is a quasi-perpetual-motion machine with a species. It differs from the ideal perpetual-motion machine both in that it has a species and in that it requires constant refueling in order to exist. It differs from ordinary machines or “organica artificialia” in that it is both self-sustaining and self-reproducing. As we already saw in chapter 2, Leibniz berates other mechanists who dream in vain of a perpetual-motion machine in the stricter sense of a machine that requires no fuel at all:

In order that men should obtain this durability of action in their machines, they now add to them a quasi-perpetual machine that is made by nature, which is of course man himself, the pilot, who repairs what is weakened or broken down in time, who applies an external force, bringing agents together with patients . . . or in some other way conserves the power of the Machine.39

In other words, artificial machines are only able to continue running because a certain kind of natural machine—a human being—tends to them by bringing them new fuel. But natural machines require no such attendance. And even if the individual animal will eventually cease functioning, in death it is still capable of a sort of perpetuity to the extent that it is capable of reproduction. Put two clocks in a room together and you will never get a third, little clock out of them; put two (appropriately selected) dogs together, and you might. This is not just a difference in the degree of complexity of the tasks that the different kinds of machine can accomplish; it is a difference that places the dog in a separate ontological class. A species of plant or animal, on Leibniz’s understanding, is that transmission of properties across generations, which, as Leibniz puts it in his polemic against G. E. Stahl of 1709–10, are like so many links in a chain.40 Leibniz writes that mating and reproduction prove the divine coordination of things, in that an individual substance requires something outside of itself, provided by divine wisdom, in order to fulfill its ends. “We have recognized a great difference between machines and aggregates or masses,” he writes,

insofar as machines have their effects and their ends by virtue of their own structure, while the ends and the effects of aggregates are born of a series of struggles, thus of the meeting of diverse machines; for, even if it follows a divine predestination, this meeting manifests more or less clearly its coordination with [the divine predestination]. Thus the worm labors on its own in the sole aim of producing silk; however, in order for another silkworm to be born, there must also be the union of the male and the female, and thus the combination of a single animal with a foreign element; for this combination shows more clearly its coordination with divine wisdom.41

Ultimately, the end of every natural machine is reproduction, but there must also be a subordinate end in order for there to be a clear fact of the matter as to what is being reproduced. Silkworms give rise to silk-producing machines; spiders, to web-making machines; humans, to contemplating machines, and the endurance of this trademark activity or officium is precisely the condition of a thing’s being the sort of thing it is at all. Ordinary machines may not have a species, but hydraulico-pneumatico-pyrotechnical machines of quasi-perpetual motion are no ordinary machines.

Biological species membership, as we have been seeing, is for Leibniz an all-or-nothing affair determined by descent from the same parents, and wide morphological variation does not have as a result greater or lesser membership in a species. Deviation from the type standard does not for Leibniz yield dogs, for example, that are any less canine than their more perfect relatives. Another way of putting this is that, for Leibniz, monstrosity is not the result of deviation from the morphological standard. Leibniz would agree neither with Aristotle, for whom widespread morphological falling-short of the species standard brings about a sort of universal monstrosity, nor with many of his own early modern contemporaries, for whom gross morphological deformation could disqualify some offspring from membership in the same species as its parents. For Leibniz, species membership is determined rigidly by the species membership of the parents, and this remains the case even when the offspring is so deformed as to resemble its parents barely or not at all. What matters is that the offspring have the special office, and this is something that is, broadly speaking, ethological rather than morphological, that is, something that has to do with the principle of activity of the creature, which is rooted in its interior nature rather than in any external markings.

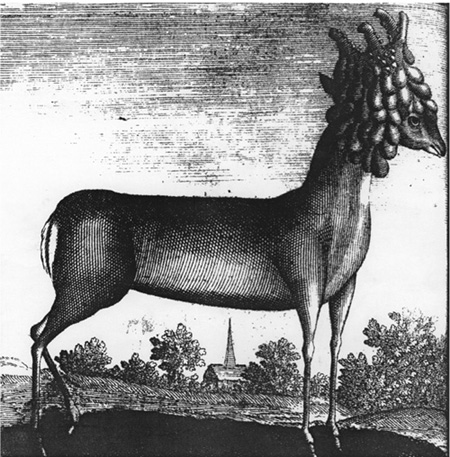

Indeed, for Leibniz it is often the prevention of an animal from doing what it naturally does, in accordance with its special office, that leads to its deformation. Thus in the Journal des Sçavans of July 5, 1677, Leibniz recounts the story of a goat with deformed horns, an “extraordinary coiffure,” as he puts it, suspected by some to be a living representative of the unicorn species.42

Leibniz explains that, in fact, this deformation is only a consequence of the restriction of the goat’s movement in its early life:

I do not know whether the frustration that he felt in seeing himself deprived of his freedom could have contributed [to his condition]; for you know what the stories teach us, that a great sadness or worry has been able in one night to change the color of a prisoner’s hair, and to make a young man look like an old one. Physicians make still more extraordinary observations, which are more related to the coiffure or the excrescence we are dealing with here, a substance that is not very hard, but that one can nonetheless rightly call the rudimentum cornuum, since it is from this substance that the horns are formed. . . . The physical cause of this excrescence could be attributed to the fact that the aqueous humor of this animal could not be dissipated as soon as it was attached, as it ordinarily is by the heat of this sort of animal that is accumulated in their bounding, leaping, and running, this great humidity mixed with the juice, the volatile salt that forms the horns, attracted the matter downward by its heaviness, and made it soft, and of a colder temperament.43

Figure 7.1 “A Goat with a Very Extraordinary Coiffure,” from the Journal des Sçavans, July 5, 1677. From the Gallica database of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

In other words, morphology cannot be separated from ethology: an animal has the form it has because it has the principle of activity that it has. To be an animal of a certain kind is to have a certain principle of activity that in normal ecological circumstances will give rise to a normal representative of the species. But an abnormal representative is no less a member of the species than one that has developed in a nurturing milieu; Leibniz’s coiffed goat is every bit a goat. Deformations are thus in no way “wonders” but rather only a consequence of the interruption of the normal developmental process. As for human beings, Leibniz frequently distinguishes between the “interior nature” and the “exterior marks” of a creature,44 and consistently offers reason as the trait that separates us from animals. Under normal circumstances, the interior nature will be legible in the exterior marks, but these marks need not be there in order for the creature to be the sort of creature it is.

In Leibniz’s account of the unusual goat we see many themes familiar from other writings on physiology and animal economy from the 1670s and 1680s. In particular, Leibniz continues to display a pronounced interest in excrescences, as he had in the Directiones of 1671. The formation of excrescences, Leibniz believes, is influenced by behavior as well as by emotion: if the animal’s motion is confined, and if, for example, as a result of its confinement it is made sad and lethargic, then its horns will develop differently than under normal circumstances. In this way, not just ethology but even psychology is relevant to the study of physiology. It is worth noting here, if only in passing, that Leibniz does not find anything contradictory about offering psychological explanations in relation to animals: for him, to identify animals as machines is in no way to deny that they may also be the appropriate objects of psychological study. It is also interesting to note that Leibniz takes the curiosity of the goat as an opportunity for the application of general physiological principles. As has already been mentioned, recent scholars45 have emphasized that the rise of seventeenth-century science brought with it a shift in the perception of “wonders,” or natural rarities, from portents, broadly speaking, to opportunities for further discovery. Leibniz’s explanation of this particular rarity in terms of the purely mechanical consequences of the failure of the aqueous humor to dissipate shows very clearly that his approach to abnormal physiology lies squarely within the modern frame of reference.

Under normal circumstances the interior nature of an animal will be legible in the exterior marks, but these marks need not be there in order for the creature to be the sort of creature it is. The interior nature determines the activity of the creature, and the exterior features are a sort of reflection or—to deploy a well-known term from the Leibnizian lexicon—a sort of unfolding of this interior nature. Given the fact that Leibniz’s metaphysics of substance is a metaphysics fundamentally rooted in activity, it is appropriate that in his analysis of one particular kind of substance—namely, the kind we would today call “biological entities”—the reality and nature of the substance should be grounded in what they do, what they are created to do, and not in how they look.

Leibniz notes that externally dissimilar features can easily give the false impression of divergent species membership, and warns that “the mixture of figures is not always a sign of the mixture of kinds.”46 He relates the story of a badly disfigured child whose suitability for baptism was debated by the local clergy. In the end, the child was baptized and declared a person par provision, that is, until such a time as his precise species membership could be established. “Here is a child,” Leibniz comments, “who was very close to being excluded from the human species simply because of his form.”47 Leibniz argues, along lines already familiar from the Directiones of 1671, that outward disfigurement cannot be a sign of the absence of a rational soul for the same reason that physiognomy is a predictively bankrupt science: “One would not be able to give a reason . . . why a face that is a bit longer, or a flat nose . . . could not coexist . . . with a soul.”48 The body may in the end be, for Leibniz, the unfolding of the soul, but this does not mean that external traits may be treated as gauges of the soul’s capacity. Leibniz’s firm commitment to the view that morphology can reveal nothing of soul-based capacities, and that it is these capacities that determine species membership, will be important for his argument, treated in the following section, against the possibility of ape-human kinship, as also, more generally, against the possibility of evolution.

Charles Darwin observes in his 1871 work The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex that once a naturalistic account of the generation of animals is admitted, creationism loses its footing and it becomes possible to think of entire species as having natural origins: “I am aware that the conclusions arrived at in this work,” he writes,

will be denounced by some as highly irreligious; but he who denounces them is bound to shew why it is more irreligious to explain the origin of man by descent from some lower form, through the laws of variation and natural selection, than to explain the birth of the individual through the laws of ordinary reproduction. The birth both of the species and of the individual are equally parts of that grand sequence of events, which our minds refuse to accept as the result of blind chance.49

Was now the danger to the species concept, inherent in reproduction from minor causes, apparent in the centuries preceding Darwin? Aristotle had a satisfactory way of explaining a wide range of natural phenomena: all natural things are a combination of matter and form; there are all sorts of ways some particular form can come to inhere in some suitably receptive matter, among these sexual generation, solar concoction, and such. In all cases, form separates itself from matter to the extent possible in imitation of the purely formal divine, and thus the more noble organisms—those capable of reuniting through self-motion to copulate when necessary—will be separated out into male and female. But with the matter-form metaphysics gone, there is no clear reason why there should remain either dimorphism in sexually generating species or regular species reproduction—what in earlier days could have been described as formal replication—among the males and females of a species.

Before Descartes, a Scholastic Aristotelian might have argued that eels and barnacles are mere rearrangements of matter that do not require any transmission of form, and that these thus differ fundamentally from horses and men, whose generation is also always reproduction. But effectively Descartes insisted that horses and men are generated as Aristotle conceded eels and barnacles must be, namely, by what Descartes called “minor causes.” Leibniz, as we have seen, avoids the account of generation in terms of minor causes by denying that generation sensu stricto happens at all. Accordingly, he is able to preserve clear species boundaries: for Leibniz a creature is a member of species x if its parents were members of x, and we can be sure of shared species membership from parent to offspring because the offspring already existed as a preformed primordium within the body of the male parent. As we will see, Leibniz also believes in the possibility of what today would be called “microevolution”: morphological change within a species over time, and thus even his preformation theory of generation does not entirely circumvent the possibility of environmentally triggered mutation. Yet for Leibniz even men with the similitude of beasts remain essentially men, a view he will develop over the course of his debate with Locke about species, and which, as we will see at the end of the present chapter, will serve as a cornerstone of his universalist anthropology.

Leibniz was sharply aware of the fast-growing evidence that the species currently walking the earth may not be exactly the same as those that lived long ago. At times, the paleontological evidence led Leibniz to propose what looks like a theory of speciation through descent from ancestors of a different species. “There has been found at Tonna, near Gotha in Thuringia,” he writes in a letter to Burnett de Kemney of 1696,

some parts of a skeleton that is by all appearances that of an elephant. Some local doctors wanted to maintain that it was a production of the earth, a lusus naturae. They consulted me; I said that I do not doubt at all but that it is ex regno animali, and if it is not from an elephant, it is nonetheless from a similar animal [d’un animal analogique], either that elephants or similar animals [animaux approchans] have lived previously in those lands, or that there were amphibious marine animals of the nature of the elephant, when a great part of the earth was still submerged. For species can be greatly changed by the span of time, as by the interval of space, as is well witnessed by the differences between our animals and those of America.50

He complains again in the same year of “the physicians at Gotha, Doctors Rabe and Bachof and others, [who] still wish to uphold the view that the remains of the elephantiform animal at Tonna are games of nature.”51

But if the remains are not games of nature, then what are they? How could one account for their presence in such a way as to avoid both the Scylla of evolution and the Charybdis of the spontaneous production of organic forms that have no representatives among real animal kinds? Leibniz’s approach is to deny that there must be actual transformation of one species into another even if species themselves can be greatly changed. With the trailblazers of modern taxonomy, Leibniz believes that species membership is rooted in descent, or, in other words, that the kind of creature a creature is, is determined exhaustively by the kind of creatures its parents were. But this is not to say that there cannot be variation, even great variation, in a species over time, as when sea-dwelling, elephant-like animals take to the land, or vice versa. The elephantiform marine mammal’s remains strongly suggested to Leibniz that offspring could be radically unlike their ancestors, and prima facie this fact threatened to weaken the like-begets-like principle to which he was attached. His strategy for maintaining this principle in the face of paleontological diversity was to hold that change over great lengths of time does not diminish the reality of species at any given time; and he does not seem worried about the potential incompatibility of the claim that, for example, as long as there are squirrels there will be dancing machines, with the possibility that someday the descendants of squirrels will be aquatic, and thus (synchronized?) swimmers rather than dancers.

Nowhere does Leibniz engage with the problem of species extinction—and relatedly, with the possibility of species change—more extensively than in that work of his that we have come to call the Protogaea. Even though Leibniz sticks to his strategy of describing morphological change as change within a species rather than change from one species into another, some commentators have discerned a burgeoning theory of evolution in this text. Horst Bredekamp, for example, cites the following passage as evidence of such a theory: “Once, when the ocean covered everything, the animals that today live on land were aquatic animals, and then they gradually became, with the retreat of this element, amphibians, and ultimately moved away, in their successive generations, from their original home. . . . But such a view contradicts the holy authors, from whom it is sinful to deviate.”52 But Bredekamp’s citation does not tell the full story. In fact, Leibniz is clear that he is not even tempted by the thought of evolution, and not just for reasons of theological correctness. Here is the full passage from the B edition of the Protogaea:53

There are those, I realize, who go so far as to propose that the animals that today inhabit the earth were aquatic, that they became amphibious as the waters retired, and that their descendants eventually abandoned their primitive dwellings. But beyond the fact that these opinions are in opposition to the holy Scripture, from which we should not deviate, the hypothesis itself offers a number of unavoidable difficulties.54

What were these difficulties? Around the time of the Protogaea’s composition, a few years prior to the discovery of the Thuringian mammoth, Leibniz becomes intensely interested in the spate of discoveries, in regions as far apart as Mexico and Russia, of fossilized mammoth skeletons. These remains were problematic both because they were vastly larger than the teeth and bones of known elephants and because they were appearing in regions that in Leibniz’s day were no longer inhabited by elephants of any size. Leibniz reasons as follows: “We can assume either that these animals were once more widely distributed across the globe than today, because their own nature or the nature of the soil has changed, or that they have been carried very far from their homeland by the strength of the waters.”55 Leibniz seems aware here of the inherent epistemological difficulties in making determinations as to the differences between the variety of past species and those of today. Simply finding an unfamiliar skeleton neither proves that it is the skeleton of an extinct species, nor, still less, that current species are descended from it. Indeed, determining paleontological species necessarily involves different criteria from those ordinarily deployed for living species: since we only have fragments of them, and these fragments are not capable of reproducing, the criterion of interfertility, or the determination of species membership in terms of the like-begets-like principle, cannot be employed. Instead, one must look to morphological criteria alone. Yet, as we have seen in the previous section, Leibniz does not believe that morphology is in general the best guide to determining true species membership.56

Because Leibniz believes (i) that morphology without consideration of the causal chain of generation cannot be a reliable guide for the classification of species, and (ii) that there are actually infinitely many species in nature, and between any two given species there is a third, intermediary species (even if it shares ancestral links to neither), it is certainly not surprising that he finds the fragmentary evidence of the known paleontological record, in which skeletal morphology is all one has to go on, insufficient for determining the past existence of now-extinct species, let alone as to the ancestral connection between past species and present ones. Even our knowledge of present species, to the extent that it is based on morphology, is deemed by Leibniz to be provisional. He writes in the Nouveaux essais, for example:

Perhaps at some time or in some place in the universe, the species of animals are or were or will be more subject to change than they are at present among us, and many animals that have something of the cat in them, like the lion, the tiger, and the lynx, could have been of one single race and now could be new subdivisions of the ancient species of cats. Thus I come back continually to what I’ve said more than once, that our determinations of physical species are provisional and proportional to our knowledge.57

Here again the amount of change Leibniz admits does not extend beyond the degree of microevolutionary adaptation any “creation scientist” today would admit. In this passage there is no evidence that Leibniz takes the “subdivisions” of a “race” to be distinct species, since nowhere does Leibniz assert here that lynxes, lions, and such, are reproductively isolated from one another. Significantly, elsewhere in the Nouveaux essais Leibniz mentions different breeds or “races” of dog that are sufficiently different in size and shape to raise the question of species difference. Leibniz responds in this case, as in the case of the giant cats, that they are evidently descended from a common ancestor, and all likely have the same “interior nature.”58 Similarly, while Leibniz reports of an unnamed traveler who maintained that “les Negres, les Chinois, et enfin les Américains” were all of different “races” from one another, and all of them from the Europeans. Leibniz insists that since “we know the essential interior of man, that is, reason,” there is no ground for believing that what we today call “racial” differences, based as they are on “exterior marks” or morphology, could ever amount to species differences. We will return to Leibniz’s theory of racial difference toward the end of this chapter.

Change over great lengths of time does not diminish the reality of species at any given time, and radically altered morphology does not fundamentally alter the special office of the creature. Presumably, in the case of the lion and its fellow felines, as long as there are large, wild cats there will be growling, meat-eating animals (or whatever Leibniz imagines their special office is), and Leibniz is not concerned to attribute to the tiger, the lion, and the lynx a special office in each case, notwithstanding the morphological diversity among these three subdivisions. Species membership, again, is an all-or-nothing affair determined by descent from the same parents, and wide morphological variation does not give rise, as a result, to greater or lesser membership in a species.

Leibniz, as we have seen, believes in the deliberate design of the organs that make up an organic body, even if much of what he writes seems to suggest that creatures have the morphology they have as a result of the influence of environmental circumstances and behavior over time. To the extent that organs are designed in accordance with divine wisdom, there is an assumption of a direct correspondence between anatomy and capacities, that is, between what the animal is capable of doing and how it is constructed. Yet Leibniz also concedes that animals may have organs designed for functions that are no longer regularly performed by that species, or that animals may on occasion be able to execute functions with organs that could not have been designed for these functions. Nowhere does the possibility of such a discrepancy between organs and functions, between what an animal is designed for and what it does, loom larger than in the question of animal language.

There is a fine line in seventeenth-century natural philosophy between the view that animals are an instantiation of rationality in their design, on the one hand, and on the other hand the view that animals themselves possess reason. That animal rationality was a position defended by libertines is well known; what has not been noted as often is that many believed that if we are to deny full rationality to animals, we must find some difference in their anatomy or design that would account for their diminished capacity for thinking, or indeed speaking. Marin Cureau de la Chambre, to cite one prominent example, argues that the rationality of animal actions—the fact that they do what is best for them in concrete circumstances—is evidence that they possess the faculty of reason:

We must conclude, [that there is] is a faculty born with [animals], which ought to be of an order as elevated, as its effects are excellent, and which consequently acts with a great knowledge. If it be so, who will not have cause to believe, that actions whose successes are so well ordered, which have so well regulated a progress and a concatenation, which so justly ties together the means with their ends, must needs be enlightened by Reason.59

Cureau de la Chambre bases this claim in part on the purported empirical evidence that there is nothing in animal anatomy that could be seen as underlying any fundamental difference in respective mental capacities:

Porphyrius, Plutarch, Raymondus Sebondus, for whom also Montaigne in his Essays hath written an Apology, were all of the same opinion with our Author, and if you will have the reasons of these and other learned men, why they have allowed Reason to Beasts, take these in brief. That most Animals have organs fit, and faculties like ours; In Anatomy the very cells of their brain nothing different.60

In the 1650s, the Baconian philosopher, John Bulwer, had argued the contrary view, that we could be certain of the absence of a soul in apes, in view of their anatomical difference from us. “Indeed, the bodies of other Creatures,” he writes, “are not capable of mans soule, because they are not of that Fabrick, temper, and constitution, if they were capable; yet, for want of fit Organs the soule could not exercise her actions.”61 In 1672 Thomas Willis similarly identifies the complexity of human action and deliberation with the elaborately folded surface of the human brain:

Those Gyrations or Turnings about in [the brains of] four footed beasts are fewer, and in some, as in a Cat, they are found to certain figure and order: wherefore this Brute thinks on, or remembers scarce any thing but what the instincts and needs of Nature suggest. In the lesser four-footed beasts, also in Fowls and Fishes, the superficies of the brain being plain and even, wants all cranklings and turnings about: wherefore these sort of Animals comprehend or learn by imitation fewer things.62

For Willis, as for Bulwer, there are sufficient physiological markers of a profound difference between humans and animals to assure us of our unique place in nature without having to leave the bounds of empirical science and engage in metaphysical disputations about the possession of a soul. Along the same lines as these thinkers, Spinoza famously went so far as to maintain that the mind just is the idea of the body, and that higher cognition is the direct correlate, under the attribute of thought, of bodily capability under the attribute of extension.

Leibniz carves out a moderate view in relation to these thinkers. He does not believe that every anatomical feature must be the correlate of some mental capacity (except, perhaps, in metaphysical rigor). Instead, he believes that it is the animal’s activity that is the reflection of divine wisdom, and, secondarily, that this activity may be better facilitated by a certain conformation of the organs. For Leibniz, as we have seen, every species has its special office, and this office is in some way or other written into the body, though not in as direct a manner as for Spinoza or Willis. In some cases Leibniz thinks that animals may have the proper conformation of organs to do things that do not belong to their special office. For example, in the Histoire de le l’académie des sciences of 1706, we read the following report:

Without a guarantee such as that of Mr. Leibniz, who was an eyewitness, we would not dare to report that near Zeitz, in Meißen, there is a dog that speaks. It is a peasant’s dog, of the most common figure, and of a medium size. A small child heard it pushing out some sounds that he believed to resemble German words, and from that he got the idea to teach it to speak. The master, who had nothing better to do, spared neither his time nor his efforts, and fortunately the disciple had dispositions that it would have been difficult to find in another. Finally after some years the dog knew how to pronounce approximately thirty words, among which are Thé, Caffé, Chocolat, Assemblée, French words that passed into German without any change. It is worth noting that the dog was already three years old when it began its schooling. It only speaks as an echo, that is to say, after its master has pronounced a word, and it seems that it only repeats the words by force, and in spite of itself, although it is not at all mistreated. Again, Mr. Leibniz saw it and heard it.63

At least since Aristotle the idea of talking animals (if not Francophone animals) was associated with prephilosophical or mythical ideas about nature: Aristotle insists in the Politics, for example, that “Man is the only animal that has the gift of speech” (I.2), and with this lays down what would be a nearly universal commitment of subsequent philosophy. Richard Serjeantson traces the reception of Aristotle’s view in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in such figures as Kenelm Digby, Vossius, and John Ray, noting that “an unsuitable anatomy . . . was one of the principal reasons for denying animals the capacity for articulate speech. They were widely taken to lack the right equipment of palate, larynx, tongue, lips. . . . For this reason . . . the miraculous constitution of the human speech organs served as a powerful proof in natural theology.”64

But why are the brutes mute? Is it that they could not possibly have anything to say, or is it simply a contingent fact about their physiology that their limp tongues do not permit them to communicate what they are nonetheless thinking? Could the exceptional case of a talking dog reveal the thought that is always hidden in the canine body, usually unable to be expressed as a result of the unsuitable conformation of the canine vocal organs? We may be certain that Descartes would have taken the case Leibniz reports on, as well as the case discussed in Gabriel Naudé’s 1648 edition of Rorarius’s Quod animalia bruta saepe ratione utantur melius homine (That Brute Animals Often Make Better Use of Reason Than Men), with which he was likely familiar, as one of mere imitation rather than true speech. In a letter to Henry More of April 15, 1649, Descartes writes: “I think that even in us all the motions of our limbs which accompany our passions are caused not by the soul but simply by the machinery of the body. The wagging of a dog’s tail is only a movement accompanying a passion, and so is to be sharply distinguished, in my view, from speech, which alone shows the thought hidden in the body.”65 Perhaps nowhere is Leibniz more anti-Cartesian than in his views on the interior lives of animals. As he writes in a text of the early to mid-1680s:

I fear the opinion of the Cartesians will eventually be refuted by experience if men were to take greater pains in teaching animals. Descartes, writing to More, correctly asserts that he knows demonstratively that all the actions of beasts are able to be explained without invoking souls, so that the contrary cannot be demonstrated, but this needs to be understood according to metaphysical rigour, by which this cannot be demonstrated in relation to men.66

In other words, though God could have created the world such that he and Leibniz were the only existing beings, short of this possibility there is no greater evidence for the real, independent, substantial existence of other human beings than there is for that of animals. Nonetheless, as we have seen, Leibniz’s report from Meißen tells of a case of mere imitation. Leibniz disagrees with Descartes that true speech is the only shibboleth for discerning mental activity in another being while nonetheless maintaining that speech is the exclusive office of human beings, the only species that, in addition to being a sort of embodiment of God’s reason, is also itself capable of exercising the faculty of reason.

Whether dogs possess a degree of reason or not, their species difference from human beings is clear to all. Other creatures, however, were not so easy to place squarely on the other side of an ontological divide from human beings, and here as well the question of language played a very important role.

There are creatures in the world, Locke announces in his Essay concerning Human Understanding, that “have shapes like ours, but are hairy, and want Language, and Reason.” He also identifies people among us, “that have perfectly our shape, but want Reason, and some of them Language too.” He goes on to describe ever more unlikely beasts: “There are Creatures, as ’tis said . . . that with Language, and Reason, and a shape in other Things agreeing with ours, have hairy Tails.” There are, he goes on, “others where the Males have no Beards, and others where the Females have.” He infers from these oddities that the discrete reality of the human species cannot be maintained. “If it be asked,” he reasons,

whether these be all Men, or no, all of humane Species; ’tis plain, the Question refers only to the nominal Essence: For those of them to whom the definition of the Word Man, or the complex Idea signified by that Name, agrees are Men, and the other not. But if the Enquiry be made concerning the supposed real Essence; and whether the internal Constitution and Forme of these several Creatures be specifically different, it is wholly impossible for us to answer.67

In his response to Locke in the Nouveaux essais, Leibniz also takes up the problem of the “Orang-Outang” (which is to say, in the nomenclature Leibniz adopts from Edward Tyson, a chimpanzee, or perhaps a bonobo) and speculates as to what this creature might mean for our understanding of human uniqueness:

Few theologians would be bold enough right away and unconditionally to baptize an animal that has a human figure but that lacks the appearance of reason, if it were found as a baby in the wild, and a priest of the Roman Church would perhaps say conditionally, if you are human, I baptize you.

Leibniz is evidently taking a cue from Augustine, who in The City of God writes similarly: “Whoever is anywhere born a man, that is, a rational mortal animal, no matter what unusual appearance . . . or how peculiar in some part they are human, descended from Adam.”68 For Leibniz, as for Augustine, morphological deviance has nothing to do with the possession of that special office of humanity, the contemplative rational soul, and this even in the case in which the morphology is so distorted as to conceal from outside observers whether the creature in question is human or not. Leibniz continues:

It would not be known if it is of the human race, and if a rational soul lodges within, and this could be the case of the Orang-Outang, an ape that is outwardly so similar to a man, of which Tulpius speaks from his own experience, and whose anatomy has been published by a learned Physician.69