FROM THE GOLDEN AGE

In 1889 Marti embarked on a new career in children’s publishing, founding, editing, and writing his own magazine for “the children of America” called La Edad de Oro (The Golden Age). The venture was very much in character: Marti had long had a passionate interest in education and had taken a very active role in educating the younger children of his companion Carmen Miyares.

La Edad de Oro contained, among other things, original stories and poems; adaptations of fairy tales by Laboulaye; an article on Homer’s Iliad; a “History of the Knife and Fork”; a “History of Man as Told by His Houses”; pieces on Bartolomé de Las Casas and Bolívar, San Martin, and Hidalgo (three heroes of Latin American independence); a description of the Paris Exposition; an account of a journey through “the Land of the Annamites” in central Vietnam; and the following digressive disquisition on the latest craze in the United States: pin the tail on the donkey. Four issues appeared in all before the magazine shut down because its financial backer, a wealthy Brazilian named A. d‘Acosta Gómez, withdrew his funding in anger at its absolute lack of religious content.

PIN THE TAIL ON THE DONKEY: A NEW GAME AND SOME OLD ONES

Today in the United States there is a very curious game that they call “Donkey.” In summertime, when you hear gales of laughter coming from a house, it’s because they’re playing “Donkey.” It isn’t only children who play it but grown-ups as well. And it’s the easiest thing to do. On a large sheet of paper or a piece of white fabric you draw a donkey, about the size of a dog. You can use charcoal to do it, because coal doesn’t leave a mark, only charcoal does, the kind made by burning wood beneath a mound of dirt. You could also draw the donkey with a brush dipped in ink, because you don’t need to paint the whole figure black, only the outline, the shape. You draw the whole donkey, except the tail. The tail you draw somewhere else, on another bit of paper or fabric, and then you cut it out so that it looks like a real tail. And that’s the game: putting the tail where it should be on the donkey. Which isn’t as easy as it seems, because the player is blindfolded and given three spins before he’s allowed to walk. And he walks and walks, and people stifle their laughter. And some players pin the tail on the donkey’s muzzle or its rib cage or its forehead, while others pin it to the back of the door, thinking it’s the donkey.

In the United States they say that this is a new game that has never existed before, but it isn’t really very new; it’s just another way of playing “the blind hen.” It’s very curious; children today play in the same way as children did long ago. The peoples of distant lands, who have never seen each other, play in the same ways. We often speak of the Greeks and the Romans, who lived two thousand years ago, but Roman children played with balls the same way we do, and little Greek girls had dolls with real hair, just as little girls have nowadays. In the picture, some Greek girls are placing their dolls before the statue of Diana, who was a kind of saint of that era, for the Greeks also believed that there were saints in the heavens, and little girls prayed to Diana to let them live and keep them pretty always. It wasn’t only dolls that the children brought her, for the small gentleman in the picture who is gazing at the goddess with the face of an emperor has brought her his little wooden chariot so that Diana can ride in it when she goes out hunting, as they say she did every morning. There never was any Diana, of course, nor any of the other gods the Greeks prayed to in their very beautiful poems and their processions and songs. The Greeks were like all new peoples, who believe themselves to be the masters of the earth, just as children think they are. They see that sun and rain come from the sky, and that the earth yields wheat and corn and that there are birds and animals that are good to eat in the forests, and so they pray to the earth and the rain and the forest and the sun, and give them the names of men and women and depict them in human form, believing that they think and desire just as humans do and that they must have the same form. Diana was the goddess of the forest. In the Louvre Museum in Paris there is a very beautiful statue of Diana out hunting with her dog, so fine that she looks as if she were really walking. But her legs are like a man‘s, to show that she is a goddess who does a lot of walking. And the Greek girls loved their dolls so much that when they died they were buried with their dolls.

Los niños grregos y la diosa Diana

Not all games are as old as playing with balls or dolls, or cricket, or the ball game, or swinging, or jumping. “The blind hen” isn’t that old, though it’s been played for about a thousand years in France. And children don’t know, when they are blindfolded, that this game is played to honor a very valiant knight who lived in France and who was blinded one day while fighting, but didn’t drop his sword or ask to be attended to and went on fighting until he died. The knight was named Colin-Maillard. Then the king ordered that in all the mock fights, which were called tourneys, one knight would always fight with a blindfold over his eyes, so that the people of France would never forget that knight’s great valor. And that is where the game comes from.

A pastime that seems unfit for men was that of the friends of Henry III, who was also king of France—not a brave and generous king like Henry IV of Navarre, who came later, but a ridiculous little man of the kind who thinks only of doing his hair and powdering himself like a woman and trimming his beard into a point. That king’s friends spent their lives playing and jealously quarreling with the court jesters, who hated them for their slothfulness and told them so to their faces. Poor France was in misery; the working people paid a huge tax so that the king and his friends would have silken clothing and swords with golden hilts. Back then, there were no newspapers to tell people the truth. The jesters were something like the newspapers back then; the kings didn’t keep them in their palaces just to make them laugh, but also so that the jesters could find out what was going on and tell the truth, which the jesters always spoke as if it were a joke, to the nobles and even to the kings themselves. The jesters were almost always very ugly men, either skinny or fat or hunchbacked. One of the saddest paintings in the world is a painting of jesters by the Spaniard Zama cois. All of those unhappy men are waiting for the king to call them so they can make him laugh, wearing costumes the color of an ape or a parrot, embellished with horns and little bells.

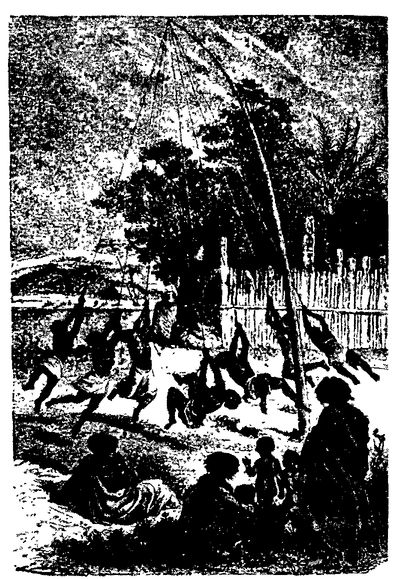

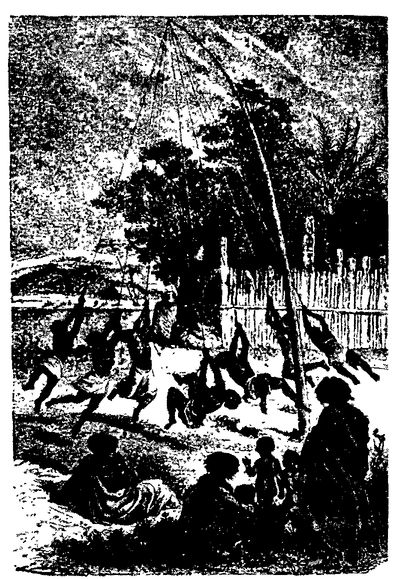

La danza del palo en Nueva leandro

Naked as they are, the blacks who are dancing their pole dance in the other picture are happier than the jesters. Countries, like children, sometimes need to run a lot, laugh a lot, and shout and jump. That’s because you can’t do everything you want to do in life, and all the things you don’t do come bursting out like that sometimes, like a craziness. The Moors have a festival of horses they call the “fantasy.” Another Spanish painter—poor Fortuny

1—has painted that festival very well. His painting shows the Moors galloping into their city at top speed on horses as crazed as they are, firing their long Moorish flintlocks into the air, stretched over the necks of their mounts, kissing them, biting them, throwing themselves to the ground, and remounting in the middle of their mad dash. They shout as if their chests were tearing open and the air is dark with the dust they raise. Men of all countries, white or black, Japanese or Indian, need to do something beautiful and daring, something dangerous and fast, like the pole dance of the New Zealand blacks. It’s very hot in New Zealand, and the blacks there are men with arrogant bodies—the bodies of people who do a lot of walking—brave men, who fight for their land as well as they dance around the pole. They go up and down on cords, winding half the cord’s length around the pole, then letting themselves drop. They send the cord flying like a swing, and they hang on by one hand, by their teeth, by a foot, or by a knee, bouncing off the pole like balls, shouting to each other and embracing.

When the Spaniards arrived, the Indians of Mexico had this same pole dance. The Mexican Indians had beautiful games. They were fine, hardworking men; they knew nothing about gunpowder and bullets as the soldiers of the Spaniard Cortés did, but their city seemed to be made of silver, and they knew how to work silver into something like lace, with all the delicacy of the very best jewelers. They were as lighthearted and original in play as at work. Among the Indians, the pole dance was a pastime that demanded great agility and daring, because they threw themselves from the top of the pole, which was about twenty yards high, and came hurtling down through the air, spinning and doing acrobatic tricks without hanging on to anything but the strong, slender cord that they made themselves, and called mecate. Their daring is said to have been staggering to behold; according to an old book, it was “horrible and appalling, and seeing it frightens and fills one with dismay.”

The English believe that the pole game belongs to them and that they’re the only ones who know how to display their skill at fairs: with the cudgel, which they grasp by one end and in the middle, or with sticks, which they handle very well. The Canary Islanders, who are people of great strength, believe that the pole was not invented by the English, but by the islanders, and it is something to see a Canary Islander playing with a pole and spinning it like a pinwheel—and fighting, too, which the children of the Canary Islands are taught to do in school. And there is a dance with a beribboned pole, a very difficult dance in which each man has a ribbon of one color, and they go braiding and unbraiding them around the pole, making loops and pretty designs with never a mistake. But the Indians of Mexico played the pole game as well as the blondest Englishman or the most muscular Canary Islander; and they didn’t just defend themselves with it, but also knew how to balance on the pole as the Japanese and the Moorish Kabyles do now. And there we have five peoples who have done the same as the Indians: those of New Zealand, the English, the Canary Islanders, the Japanese, and the Moors. Without counting the ball game, which all peoples play, and which was a passion among the Indians, for they believed that a good player was a man come down from heaven, and that the Mexican gods, who were different from the Greek gods, descended to tell him how he should throw or catch the ball. The story of the ball game, which is very curious, will be for another day.

Right now we’re talking about the pole, and the extremely difficult balancing tricks the Indians did on it. The Indians lay down on the ground, as the Japanese do when they’re about to play with balls or barrels in circuses; they laid the pole across the soles of their feet and held up to four men on it, which is more than the Moors did, because the Moors were held up by the shoulders of their strongest man, not by the soles of his feet. Tzaà they called this game: first two Indians got up on each end of the pole, then two more climbed up onto those two, and the four of them did many tricks and turns, without falling. And the Indians had their chess, and their prestidigitators, who ate burning wool and then brought it back out through their noses, but that, like the ball game, will be for another day. Because when you’re telling stories you have to do what Chichá, a pretty little Guatemalan girl, told me:

“Chichá, why do you eat that olive so slowly?”

“Because I like it a lot.”