CHAPTER 9

OPTIONS PRODUCTS

The term “option” has the same meaning in the financial industry as it does anywhere else. It gives its owner the privilege of taking some predetermined action, at a price, for a period of time. Individuals who are interested in acquiring a home may take an option on a home, prohibiting the seller from selling the home to anyone else while the option is enforced. During that time, the prospective buyers can see about securing a mortgage or continue looking at other available properties. In order to secure this option, the prospective buyer pays the would-be seller a fee. The option gives its owner the privilege of exercising the option according to the terms of the contract. At the end of the contract’s life the prospective buyer must either buy the house or let the option contract expire. At a nanosecond after the option expires the seller is free to sell the home to anyone else and at any price they negotiate. Options are tools, and as with any good tool, the value shows only when it’s properly used.

In this chapter, we’ll discuss the variations of options.

• CALL OPTIONS AND PUT OPTIONS •

There are two types of options in the financial industry: the call option, which gives its owner the privilege to acquire the underlying product; and the put option, which permits its owner to sell or dispose of the underlying product. The basic structure of an option is very straightforward. The option owner controls the action; the seller of the option has to do nothing until a buyer exercises the option. After the buyer does so, the seller must perform the terms of the option contract.

In the case of a call option, let’s suppose that it is on 100 shares of ZOW common stock, where the owner of the call option has the privilege to buy the shares at a price, $60 a share, for a period of three months. If the options owner decides to exercise the option, the seller of the call option must deliver 100 shares of ZOW to the option owner, who will pay $6,000 for the stock. If the owner doesn’t exercise the option at the end of the three months, the option will expire worthless. If this was a put option, the owner would have the privilege to sell 100 shares of ZOW at $60 per share. Should the put owner decide to put (sell) the stock, the seller of the put would be obligated to receive 100 shares of ZOW and pay the put owner $6,000. As with the call option, failure to exercise would result in the option expiring.

• POSITION TERMINOLOGY •

There are several different ways you can refer to option buyers and sellers, depending on the situation. The buyer can be referred to simply as the buyer, long the option, the holder, or the taker. The seller of the option is referred to as the seller, short the option, the writer, or the grantor. The usage of the different terms is derived from where and when a particular individual was introduced to the product and the environment they are operating in. The terms “buyer” and “seller” can get to be confusing because the buyer of an option may want to sell it at a later time, to close the position, whereas the option seller at a later time may be looking to buy, in order to close out that position.

The initial action sets the correct term. The terms “long” and “short” have their confusing aspects also. The term “long” is industry jargon for owner, but the term “short” denotes that in many cases, another action must occur. For example: “The short security position was covered with borrowed securities,” or “They sold more than they bought so they had a short position that had to be bought close to the position.” In the case of an option short position, the seller doesn’t have to do a thing unless an option owner exercised his or her privilege against it.

The short option position comes into being when an option contract granting the privilege to exercise is sold to another party—the option buyer. Generally, the seller wants the option to expire because that would mean it is worthless and the seller would keep the difference between the price the option was originally sold at and zero. The price an option is traded at is known as the premium. Therefore the seller or writer of the option wants the option to expire so that they may keep the premium.

The terms “holder” and “writer” go back ages to when the option seller actually wrote a paper contract and sent it to the buyer, who held it until they exercised the option or it expired. The option was initiated by presenting the paper document to the writer and surrendering it to be exercised. If the holder decided to do nothing, the writer would be free of any responsibility after the cutoff time at option expiration. The terms “taker” and “grantor” are not used in the United States, but they are used in other countries. The most common terms used in the United States to differentiate the option position are:

Sales personnel = Buying and Selling Operations and accounting personnel = Long and Short

|

Owner |

Seller |

|

Buyer owns the option, has the privilege to: exercise it or sell it. |

Writer either: honors the contract if exercised, or buys it. |

All options expire. Listed options, those traded on an exchange, enjoy an active secondary market where they are traded in and out of positions much easier than options traded in an over-the-counter market.

Underlying Issue

The product or issue underlying the option can be just about anything. For example: As I said earlier an individual interested in buying a home, who is also concerned about arranging financing, can “take an option” on the house that would restrict the seller from selling it during a predetermined time period. The word “option” appears when you acquire a new automobile. It comes with standard features and the other features that you can add on are optional. You will also see the word “option” on restaurant menus, where accompaniments to what you order are optional, in vacation packages, in your telephone contract package, apps on your mobile phone, and on and on. The financial industry uses the option products as part of many different types of strategies. From being a surrogate for the underlying product, where the buying of call options on the ZAP common stocks are used instead of buying the actual stock, or to being used as primary exposure reduction vehicle, by establishing offsetting options positions against it.

Among the underlying financial products used for options are stocks, baskets of stocks, indexes, debt instruments of all types, interest rates, currencies, commodities, and futures. One option contract usually supports one trading unit of the underlying product. For equity options in the United States, one option covers 100 shares of the underlying stock priced in dollars; in the United Kingdom, one equity option covers 1,000 shares priced in pence.

In the futures product, one option covers one future contract. In the case of those underlying products that do not have set underlying trading sizes, the contract size is determined by the exchange on which it initially trades, or in absence of the exchange (i.e., over-the-counter), the contract sizes are stipulated in the option’s specification document. This document, known as the confirmation, or terms sheet, is especially important in certain over-the-counter options where the contract size is negotiated between parties.

Option Structure

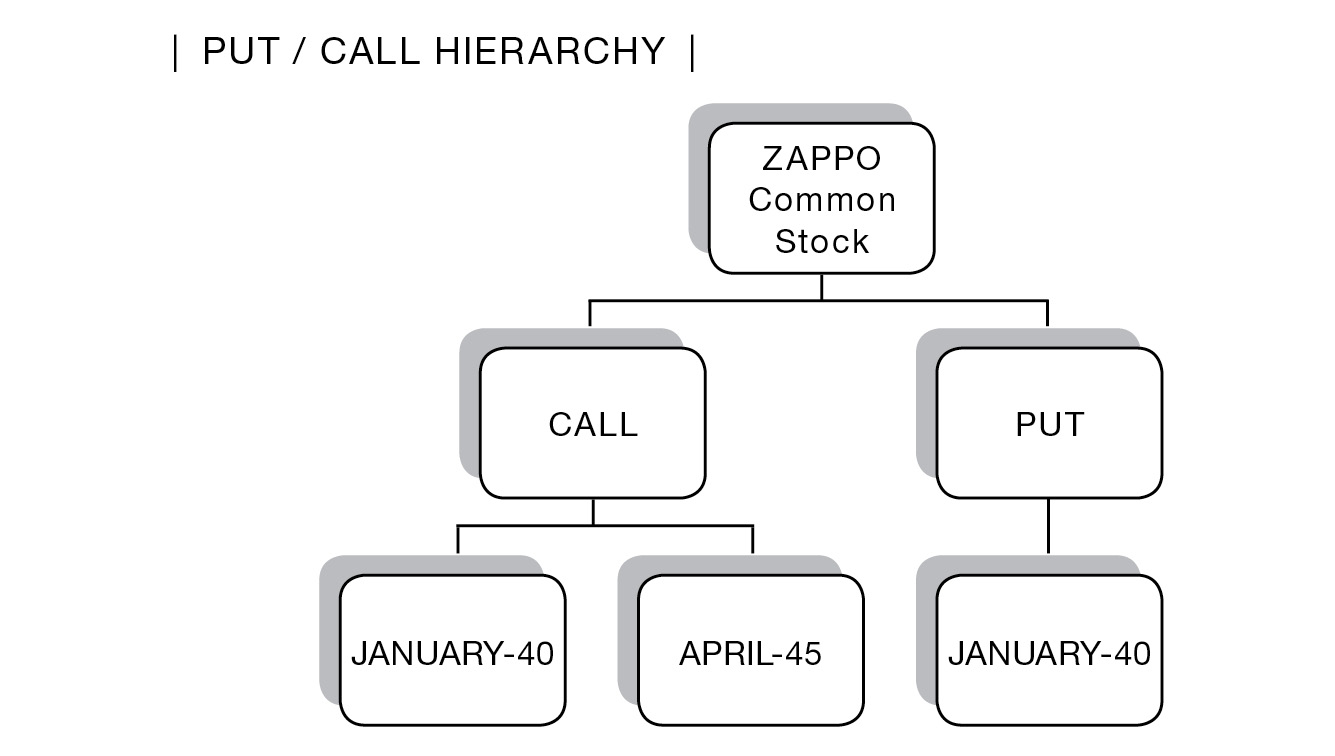

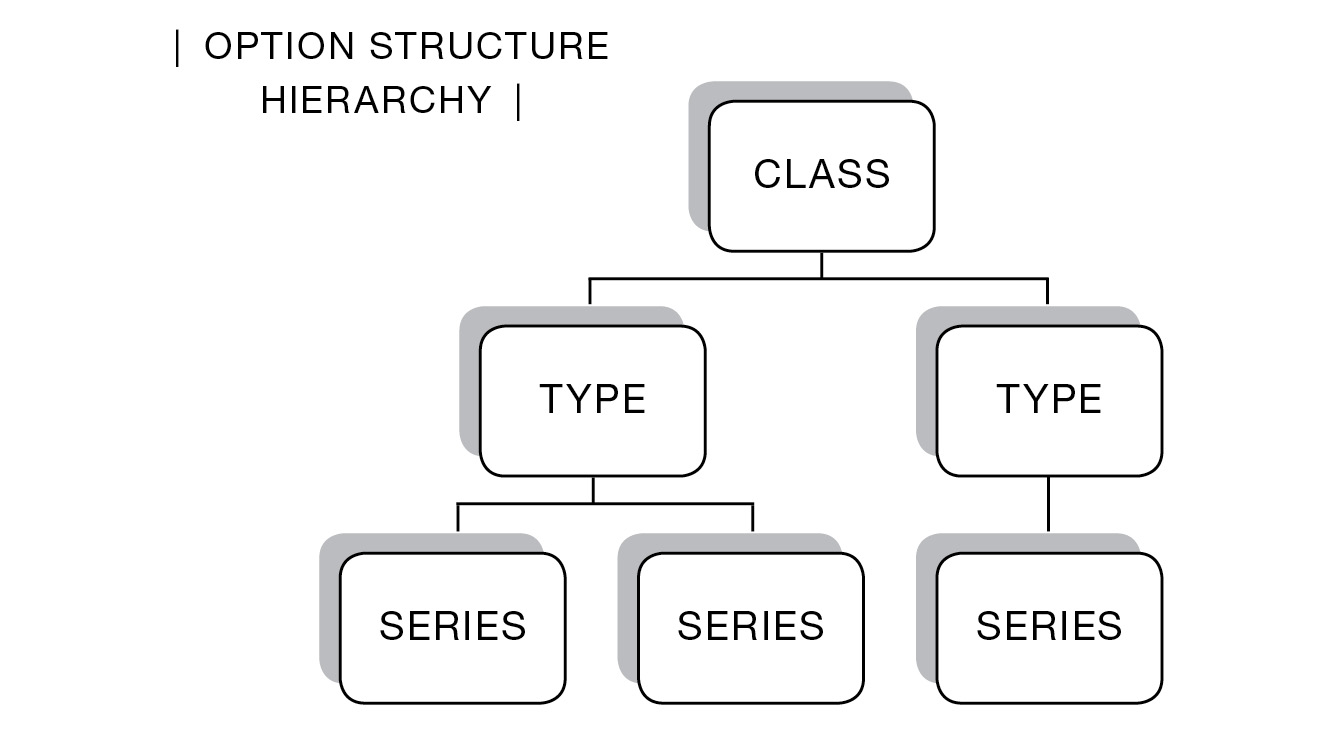

We’ve already discussed the types of options available and the underlying product. Now, let’s talk about structure. In option jargon, the term “class” refers to the underlying issue. All Loster Corporation common stock options are from the same class, and all index options are from the same class, etc. Put or call options are referred to by the “type” of option. Index-based call options on a particular index are of one class and one type; index-based put options on the same particular index are of the same class but a different type. Currency-based call options on a particular currency are of one class; put options on the same currency are the same class but a different type. Therefore if we were looking at equity options on two different stocks, we would be looking at two “classes” (each stock) and four types (each of the underlying stocks would have a call type and a put type).

Next is the term “series.” The series is made up of the strike price (the transaction price should the option be exercised) and the expiration date of the option. A call on ZAP common stock with a strike price (or “exercise price”) of 40 would cost the call owner $40 per share to call in (buy) the shares, should the call be exercised. As 100 shares is a trading lot in the United States, the exercise of the call would necessitate the asset exchange of $4,000 for 100 shares of stock to settle the exercise (plus applicable commissions and fees). The strike price of the option was $40, which would be the price used for settlement of the exercise regardless of what price the stock is actually trading at at that time. The same holds true for a put option. If it was a $40 strike price put that was exercised, the exerciser of the put would be exchanging 100 shares of ZAP for the receipt of $4,000 less applicable commissions and fees.

The strike price of an option is either negotiated between parties (over-the-counter options) or set by the issuing authority (listed options). Listed options are issued under a set regimen with strike prices issued at varying levels, such as five-point intervals for options whose underlying securities are trading at a price between $X and $Y. (There are special exceptions to the regimen, such as stock dividends, for example.)

The description of an option includes the expiration date. Many option products that trade on exchanges have set expiration dates. For example, standard equity options that trade on U.S. exchanges expire the Saturday after the third Friday of the expiration month. The expiration date for over-the-counter options is negotiated. Options Clearing Corporation, the industry organization responsible for issuing all exchange (listed) traded options, also issues weekly options on selected equity and ETF issues.

In listed options, call or put options on the same underlying security that have the same expiration month and the same strike price are considered to be from the same series. Because listed options have set strike prices and expiration dates comprising the series, they trade in fairly liquid markets. Therefore the basic structure of an option is: Type (put or call), Class (underlying issue), Series (expiration month or week and strike price).

Let’s say, for example, that it’s a call on the common stock ZAP with an expiration of April and a strike price of $40. The basic structure would be Call ZAP Oct 40 call (owner has privilege to buy) on 100 shares of ZAPPO Corporation common stock expiring the Saturday after the third Friday of the expiration month at a price of $40 per share.

Option Symbology

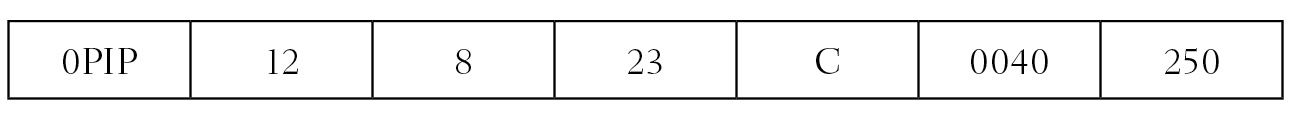

When listed option trading began, a pattern was established to identify the option. The options in question were all based on common stock. The strike price internal was 5 points assigned to letters A through T, and expiration months were divided between calls and puts. As calls were traded, first the letters A through L were used to designate call options, and M through X were used to designate put options. So a call on Pipper Company common stock with a strike price of 40, expiring in April, would be coded PIP (stock symbol) D (4th letter = 4th month) H (5 pt interval × 8 = 8th letter). This identification methodology held for a while, but as there was a proliferation of products the coding became more and more difficult to apply.

Long-term Equity AnticiPation Securities (LEAPS), for example, which are issued for more than a year, required special accommodations for the year of expiration. Prior to their introduction, the year the option expired was not important as the longest listed option issued was for nine months. Another problem occurred when any security rose or fell 100 points during the duration of an option contract. Though rare, a stock could rise from $40 per share to $140 per share, which would require a change to its symbol. If, for example, the above-mentioned PIP was trading at 40, the symbol D was used to designate 40, 140, 240, etc. What if PIP rose in price to 140 while the 40 calls were still trading? As the designation PIP D H was already being used for the $40 option, the convention was to change the stock symbol. The more the old methodology was manipulated, the more confusing it became. In the year 2010, a new methodology was introduced.

The new symbology contains 21 bytes, divided as follows:

|

Symbol |

6 bytes |

|

Year |

2 |

|

Month |

2 |

|

Day |

2 |

|

C/P |

1 |

|

Strike Price |

5 |

|

SP Fraction |

3 |

|

Total |

21 |

An equity option would be as follows:

A call on PIP common stock with a strike price of 40.25 (1/4) expiring August 23, 2012

Premium

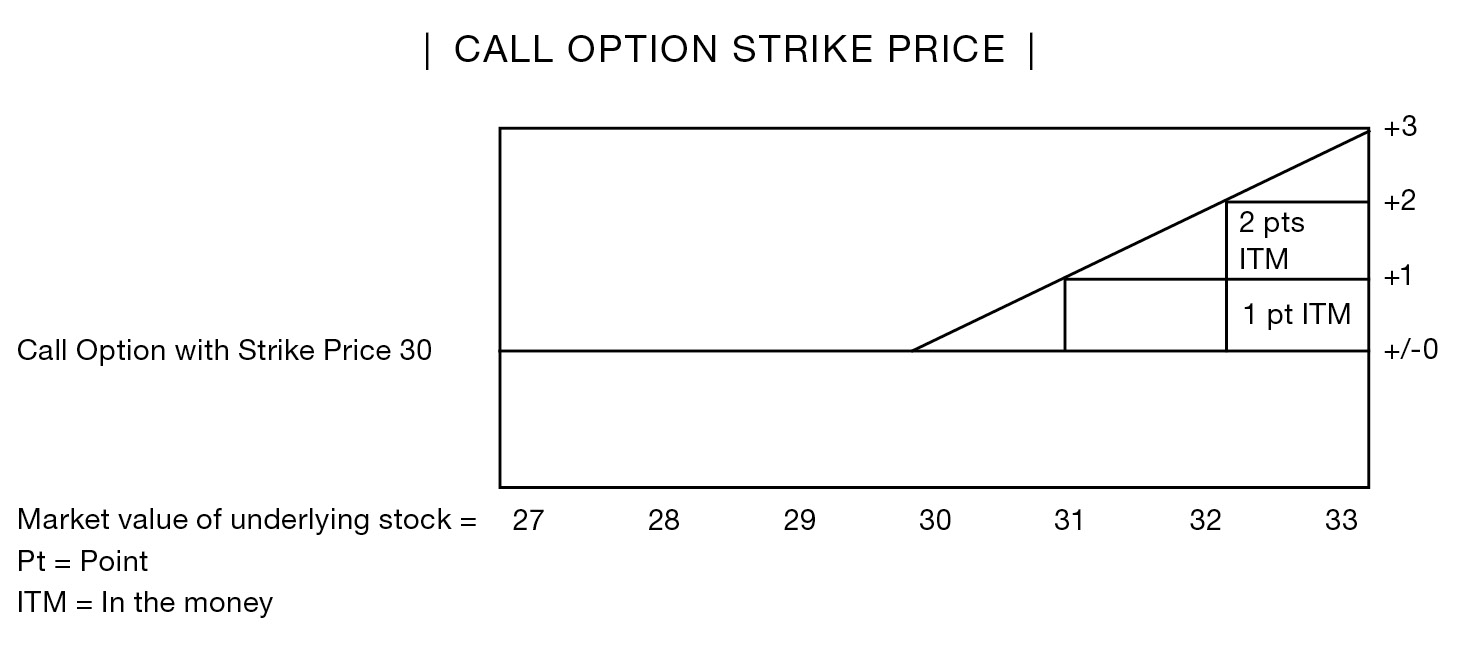

The term “premium,” as most commonly used, refers to the option’s price, which is made up of two component parts. One part is “intrinsic” value (or “in the money” value), the other is “time” value. Intrinsic value is a value that must be in the option price. A call option with a strike price of $30 which is on a security whose current market value is $34 has an intrinsic value of 4 points or $4. If a person was given the option for free, that person could “call in” the stock at $30 per share and sell it at $34 per share, earning a profit of $4 per share or $400 on the 100-share lot. Therefore, the cost of the option must be at least 4 points.

A put with a strike price of $60, which has an underlying security with the value of $54, has 6 points intrinsic value. If the option owner was given the option for free and exercised it, the put owner would be acquiring the stock at $54 per share or would have already owned the stock which has current market value of $54 per share and would be “putting it out” at the strike price of $60 per share, thus earning a 6-point profit. Again, “intrinsic value” is synonymous with the term “in the money.”

The relationship between the option’s strike price and the underlying issue market value reveals how much of the premium price is intrinsic value and how close the option is to being executable.

An option can be “in the money,” as in the example above, or “at the money,” meaning the strike price of the option and the value of the underlying issue are equal, or “out of the money,” which means that if the option was exercised, the option owner would have a loss. As option products span time, from issuance to expiration, the value of the underlying issue exists in a dynamic environment being changed by market forces. It is therefore possible that the option can swing from being in the money to being out of the money and back several times during its life.

It must be noted that the relationship being discussed is between the strike price of the option and the underlying issue’s value. This is not to be confused with trading profit or loss, which includes the price of the option that was paid at the time of purchase and the price of the option received at the time of sale. This is why the example above mentions that the option was given to the owner for free, like a gift.

• EXERCISE CAPABILITIES •

One item that all option products share in common is that they expire. When they are about to expire, the underlying products that support the various products become the focus of attention. At expiration, out-of-the-money options expire. At-the-money options are usually allowed to expire also. The term “expire” is valid in this terminology because the option ceases to exist. Options that are in the money and still in position will either be traded away or exercised.

Those that are “traded out” close the option and the position ceases to exist. Once an option is exercised, it ceases to exist and the owner has to either receive, in the case of a call, or deliver, in the case of a put, the underlying security, issue, or equivalent against payment. The writer is on the opposite side. In the case of a call, the writer must deliver against payment; in the case of a put the writer must receive against payment. An exception to this pattern is cash settling options where, on exercise, the owner of the option receives payment and the writer pays regardless if it is a put or a call. Therefore, with options that are cash settlers, the owner of an IND index call option with a strike price of 350 will receive 6 points if the index is at 356 on exercise and the owner of an IND 350 put option will receive 8 points if the index is at 342. Assuming the value of the index is times $100, the call owner would receive $600, and the put owner would receive $800. It must be noted, though, that for every long or owner position there must be an offsetting short or writer position.

Exercise Privilege Factors

The exercise privilege that goes to the owner of the option is dependent on one of two factors. First, the option may be the American form of option, which can be exercised any time during its life, but only in the money options. The other popular form of option is the European form. It is exercisable only at the end of its life, again only if it is in the money. The American form of option is found in equity options that are listed for trading on option exchanges and for many over-the-counter transactions (as in the stock options). The European form of option can be found in many of the listed index options that are traded because of their trading relationship to another product called futures. The European form is also popular in over-the-counter options where the terms are negotiated.

Exercise Price

In either case, once the option is exercised, the participants in the contract must perform their respective duties. In the case of a call equity option, the buyer must be prepared to pay for the receipt of one unit per option (100 shares of common stock) of the underlying security. The writer of that option must be prepared to deliver 100 shares of the underlying security. Payment will be the strike price agreed to between the buyer and seller, also known as the exercise price. Therefore, the owner of a ZAP call with a strike price of 50 who exercises the option must be prepared to receive 100 shares of ZAP common stock and pay the exercise price of $5,000 (100 × $50 = $5,000). In a similar vein, the owner of a put option on a stock called, let’s say, WOW, with a strike price of 30 upon exercise, must deliver 100 shares and receive payment of $3,000.

In both of the previous events, while the customers’ accounts are adjusted to accommodate the exercise of the option, the actual securities and cash involved become part of the firm’s daily operating systems and flow with other securities transactions into that day’s settlement cycle.

• THE CUSTOMER’S STRATEGY •

One of the questions that always surfaces is: what makes customers decide at expiration to either exercise the option, trade it out, or let it expire? The answer will depend on the customer’s strategy.

For example, if Ms. Jenna Raite owns stock for a good period of time, she could take the profit she currently has in that security if she sells it today. On the other hand, she is concerned that the price may go higher, thereby increasing her profit. Then again, the stock may fall in value and she would give up some of her profit. She might consider buying a put, which gives her the right to sell the stock at the current price. While this would cost Jenna some of her potential profit on the option premium, it would protect her from losing more, and the preset price is guaranteed to her as long as the option is outstanding. Jenna would simply exercise the option.

If, on the other hand, the stock has risen in value over the period of the option’s life, the increase in stock value would be used to offset the cost of the put option, and once that is neutralized, further increases in the stock’s price only add to the profit. If it’s an out-of-the-money put, and it had a long time to go before expiration, and if Jenna was more confident that her stock profit was quite secure, she could sell the put option as it neared expiration and, if the value of the underlying stock hadn’t changed, she could sell the put out for less than it was acquired out, thereby recouping some of the cost. The premium on an out-of-the-money option is always time value, which dissipates as the option ages and nears expiration. Time value is a wasting asset.

A call option on equities at expiration is another tool. Let’s suppose a customer, Della Whear, thought that RIP was a good security to buy. As Della does not have a lot of money, she cautiously bought a call option going out for eight months on RIP with a strike price of 30. When she bought the option, RIP was at $27 a share, so the option was out of the money. The call cost Della 2 points. Over the eight-month period of time, Della’s assessment of the stock proved to be correct. The stock rose, and at expiration, it’s trading at $40 a share. Della’s option, with a strike price of $30, has 10 points of intrinsic value. As we are at the option’s expiration, there isn’t any time value left in the premium. Della has a choice: take her 8-point profit (10 points intrinsic value minus the 2 points cost of the call = 8 points) and sell the option, or exercise the option and buy a $40 stock at a price of $30 a share, hoping that RIP increases in value even more. Of course there is a downside. With the option Della could only lose $200 plus expenses. If she converts it to stock through exercise, she can lose as much as $3,000 for the stock purchase, plus $200, the cost of the option, plus commissions paid the broker-dealer, plus other expenses if the stock went bankrupt.

• INDEX OPTIONS •

The next product we will look at is index options. These are options that trade on a multitude of indexes such as the S&P 500. The distinguishing feature of these option products is that they are cash settlers. On exercise, securities are not delivered or received. Instead the owner of the exercised option will receive the cash difference between the option strike price and the closing or assigned value of the index. On exercise, the determining price for settlement is the closing or adjusted price for the index, which means that during the trading day, the index value at any moment cannot be used for exercising purposes. The owner of an index option cannot exercise an index option the way an owner would a stock option or one that has a deliverable as a result of the exercise.

For example, Mr. Carl Lee buys a stock call option on 100 shares of SAW common stock, a call option that has a strike price of $40 per share when the stock’s price is at or below $40, so it is out of the money. Let’s assume further that one day the stock opens for trading at $40, then suddenly rises to $50 a share, and closes that day at $40 per share. Carl can give instructions to call the stock in at $40 per share and sell the optioned stock during the day at $50 per share versus the exercise the same day. In the case of an index option, since its value is computed at the end of the day, Carl could not do that type of transaction because he has nothing to sell.

For another example, if Ms. Ivy Green owns an index option with a strike price of 500, and one day the index opened at 500 and rose to 550 during the day, then fell back to 500 at the end of the trading day, there isn’t any exercise action Ivy can take because the closing value of the index determines the index’s value. Let’s continue with our make-believe index at 500. Let’s suppose the client, Ivy Green, owns a call option on the index with a strike price of 500. At the end of a period of time, the index is trading at 550. That is the closing price on a given day. Ivy decides to exercise the option. The next day her account will be credited the 50 points × $100 difference or $5,000. The writer’s account would be charged that amount.

In the case of a put option that is a cash settler, let’s suppose that Ivy owned a put with a strike price of 500 and at the end of the trading day the index closed at 490. Ivy would exercise the option and receive the 10-point difference. In either case, with a cash option, put or call, the exerciser receives the currency. The writer pays for the exercise.

• CURRENCY OPTIONS •

The last variation of an option for settlement will be a currency option that is a put or call using currency as the underlying security. Most of the currency options traded on the exchanges in America are dollar denominated, meaning the currency you are going to settle the trade in is the U.S. dollar. You’re going to pay the premium in U.S. dollars and profit or loss will also be in U.S. dollars. However, when you go into the over-the-counter market, that exchange changes. You could buy a currency option denominated in British pounds, in the euro, Japanese yen, etc.

The payment currency will be determined by the structure of the option and its specifications. Currency options are usually quoted or displayed as follows: first currency divided by the second currency. For example, in a GBP/USD option, how many U.S. dollars do you need to buy one British pound?

The U.S. dollar is trading at $1.50 to the British Pound. Ms. Lilly White is planning to vacation in England in a few months. From what she has read, she believes that the dollar will weaken against the pound. If that is true, the cost of the vacation will escalate. One currency is the commodity that is being bought or sold, the other is the currency that is used to pay for the transaction. While in the United Kingdom, Lilly spends £10,000. If the conversion rate is $1.50 to £1.00, it will cost Lilly $15,000. If the dollar strengthened against the pound so that the conversion rate was $1.30 to the £1.00 it would cost Lilly $13,000, a savings of $2,000 for the same vacation. If the dollar weakened against the pound so the conversion rate was $1.70 to the £1.00, the same vacation would cost Lilly $17,000, or $2,000 more.

While Lilly knows there are several products that would “lock” in the rate, Lilly decides to buy a six-month call with the strike price of $1.50. If after her vacation and the options are due to expire, the U.S. dollar is $1.65 to £1.00, she calls in her option and uses the profit to offset the extra cost of her vacation.

• FUTURES OPTIONS •

The final version of options we will mention in this chapter are options on futures, which we will discuss more in a later chapter. As we have stated previously, futures are another derivative with their own underlying product. Therefore, an option on the future gives you the privilege, not the obligation, to buy or sell the underlying future. The future itself will have a delivery date, the delivery date will then determine when the product must be delivered, and of course the future itself determines what must be delivered. We have options on futures on indexes and not a real tangible product in any of the three—so can they even be assumed to be real? That is something to think about.

In the next chapter, we will go deeper into option strategies.